Abstract

We use a coarse-grained protein model to characterize the critical nucleus, structural stability, and fibril elongation propensity of Aβ1−40 oligomers for the C2x and C2z quaternary forms proposed by solid-state NMR. By estimating equilibrium populations of structurally stable and unstable protofibrils, we determine the shift in the dominant population from free monomer to ordered fibril at a critical nucleus of ten chains for the C2x and C2z forms. We find that a minimum assembly of 16 monomer chains is necessary to mimic a mature fibril, and show that its structural stability correlates with a plateau in the hydrophobic residue density and a decrease in the likelihood of losing hydrophobic interactions by rotating the fibril subunits. While Aβ1−40 protofibrils show similar structural stability for both C2x and C2z quaternary structures, we find that the fibril elongation propensity is greater for the C2z form relative to the C2x form. We attribute the increased propensity for elongation of the C2z form as being due to a stagger in the interdigitation of the N-terminal and C-terminal β-strands, resulting in structural asymmetry in the presented fibril ends that decreases the amount of incorrect addition to the N terminus on one end. We show that because different combinations of stagger and quaternary structure affect the structural symmetry of the fibril end, we propose that differences in quaternary structures will affect directional growth patterns and possibly different morphologies in the mature fiber.

Keywords: aggregation, amyloid, Aβ peptide, molecular dynamics, Alzheimer's

Introduction

The aggregation of peptides or proteins into ordered amyloid fibril morphologies is associated with over 20 human diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, dialysis-related amyloidosis, and bovine spongiform encephalopathy.1,2 The fibrils have a characteristic “cross-β” structure, where intermolecular β-sheets run along the long axis of the fibril, stabilizing the assemblies that can extend to micro-meters in length.2 Although early attention focused on the toxicity of the amyloid fibrils as the cause of disease, it is now hypothesized that oligomers formed during early aggregation are actually the major toxic species.3,4 This shift underscores the need to develop an understanding of the entire aggregation process that ultimately leads to the specific structure of the final amyloid fibril.

Alzheimer's is a neurodegenerative disease linked to the aggregation and amyloid fibril formation of a set of short ∼40 residue peptides, amyloid β (Aβ1−39,1−40,1−42), created by proteolytic cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP).5 These fragments contain part of the C-terminal region of the APP protein, and are known to be highly prone to fibrilization in vitro and in vivo.6-10 The structure of the monomeric peptide has no well-defined folded state, although tertiary structures that are dependent on solution conditions have been proposed from experimental and simulation work.11-14 The backbone conformation can vary from α-helical structure in non-polar solutions as determined by solution NMR,11,12 to disordered N-terminal and C-terminal tails with a consistent turn region, as determined from electrospray mass spectrometry and implicit solvent molecular dynamics.13,14 The structure of the Aβ21−30 sub-peptide, encompassing a proteolysis resistant region of the full-length sequence, has also been determined by NMR.15

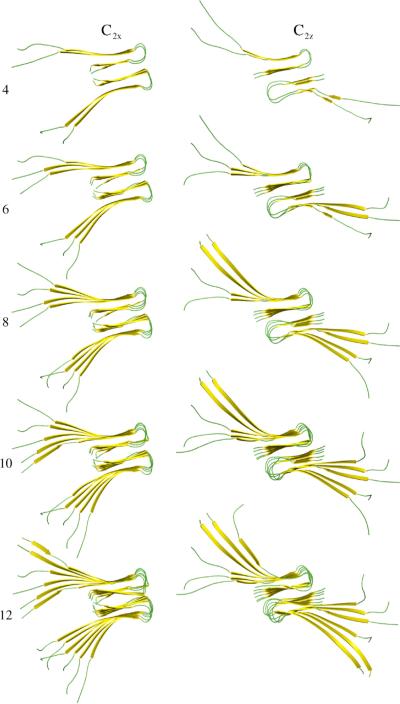

At the other extreme, the complete Aβ1−40 amyloid fibril state has been studied extensively by Tycko and co-workers, who have published a series of model structures based on constraints from solid-state NMR.16-20 The proposed structure is shown in Figure 1 and is described as U-shaped monomers with two in-register parallel intermolecular β-sheet regions (N and C-terminal β-sheets); the cross-section of the fibril is composed of two monomers with hydrophobic C-terminal regions in van der Waals contact. The original NMR data19 supported two possible intra-fibril contact types (unflipped and flipped) for the C-terminal β-strand, and eventually the unflipped form was eliminated on the basis of tertiary side-chain–side-chain contacts.16

Figure 1.

Examples of starting structures for C2x and C2z symmetry forms. Protofibril seeds composed of four, six, eight, ten, and 12 (14−20 not shown) monomers were simulated for protofibril stability.

Furthermore, two quaternary structures denoted as C2x and C2z were proposed,21 based on approximate C2 symmetry around the x axis (approximately orthogonal to the fibril axis and parallel with the β-strand directions) and C2 symmetry around the z axis (parallel with the fibril axis), respectively, and shown in Figure 1. Note that these are only pseudo-symmetry designators since there is imperfect matching of side-chain interdigitation in the C-terminal region on opposite subunits of the relevant protofibril symmetry axis in both cases. More complete NMR data revealed that only the C2z quaternary structure was likely to be formed in vitro on the basis of specific 2D NMR cross-peaks that give tertiary contacts that are inconsistent with the C2x quaternary form.16 Most recently, however, a fibril made from shortened, mutated Aβ monomers covalently linked at the N termini created fibrils with a likely C2x symmetry, indicating that the C2x form may be found under certain conditions.22

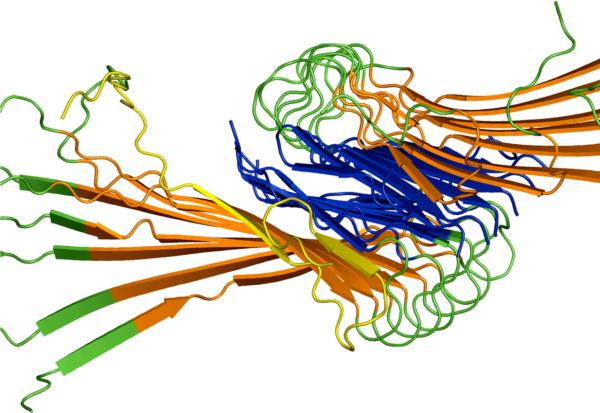

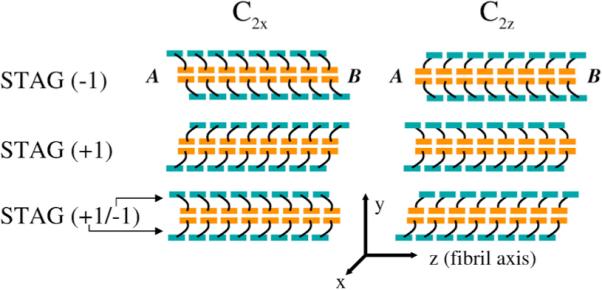

Finally, the NMR data also support interdigitation of the N-terminal and C terminal β-strands to form side-chain contacts with a particular “stagger” of N-terminal and C-terminal hydrophobic contacts,16 shown schematically in Figure 2. On the basis of the results of isotopic dilution studies, side-chain contacts are proposed between the C termini of monomer i with the N termini of monomers i + 1 and i + 2 (STAG (−2)) or between the N termini of monomer i with the C termini of monomers i + 1 and i + 2 (STAG (+2)).16 In totality, the solid-state NMR work is a truly seminal contribution to the amyloid field, since these experimental models have provided well-defined structural constraints on the “folded state” of the Aβ1−40 monomer in the context of the formed fibril.

Figure 2.

Interdigitation of the N and C-terminal β-strands to form side-chain contacts between different monomer chains introduces a stagger in the strand alignments. Side-chain contacts (from top to bottom) between the N termini of monomer i with the C termini of monomers i + 1 and i + 2 (STAG (+2)), between the N termini of i with the C termini of i and i + 1 (STAG (+1)), between the C termini of monomer i with the N termini of monomer i and i + 1 (STAG (−1)), or between the C termini of i with the N termini of i + 1 and i + 2 (STAG (−2)).16 Our model relaxes naturally to the STAG (−1) definition.

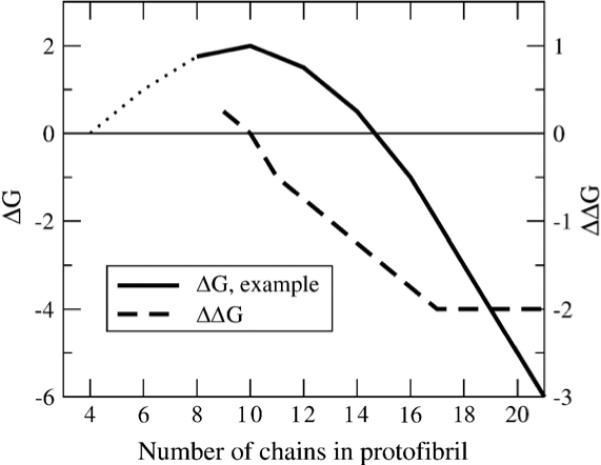

Given the possible toxicity of the earlier protofibril states, the focus is now to understand how the Aβ monomers assemble into the highly ordered mesoscopic fibril, as proposed by the NMR experimental models. The mechanism of fibrillization of full-length Aβ peptides (Aβ1−39,1−40,1−42) has been shown to follow an apparent nucleation-dependent polymerization,9,10,17,22 whereby a small number of monomers associate through a free energy barrier corresponding to a critical nucleus size, beyond which initiates a gradient of favorable free energy or “down-hill” polymerization into a macroscopic fibril (Figure 3).23 However, the structural characteristics and oligomer size of this ensemble of fibril nucleating species have yet to be determined, and the mechanism of monomer addition is unclear. This is due, in part, to the limited access of experimental characterization to this earliest aggregation stage, thus providing an opportunity for theoretical studies to bridge the experimental gap between the monomer and fibril endpoints and to develop testable hypotheses.

Figure 3.

Free energy profile for the nucleation-polymerization reactions. Typical free energy (ΔG) profile and slope of ΔG (ΔΔG) versus the number of chains in the protofibril for fibril formation by a nucleation-dependent polymerization mechanism. At high numbers of chains, the protofibril is stable and free energetically favorable, and the free energy benefit to adding chains is constant, as seen in a constant slope of ΔG. Since the slope of ΔG is constant in this regime, the free energy benefit to adding a chain or free energy cost for removing a chain is the same as in an infinite fibril. As the number of chains decreases, the free energy change for removing chains decreases, indicating that the fibril is approaching the number of chains in the critical nucleus. At the critical nucleus, the least free energetically favorable species, the slope of ΔG is zero. (Typical ΔG data adapted from Ferrone23).

Many computational studies using coarse-grained as well as all-atom models have focused on the formation of the antiparallel β-sheet structure by sub-peptides of Aβ, particularly Aβ16−22.24-26 The antiparallel structure of these peptides, however, suggests that studies of the steps in fibril formation of this system will not lead to information regarding the nucleation and fibril forming properties of the in-register parallel structures formed by the full-length Aβ1−40 and Aβ1−42 peptides. More recent simulation work has therefore focused on the full-length Aβ peptides. Coarse-grained simulations of the Aβ1−40 and Aβ1−42 monomers and dimers reported by Stanley and co-workers have reproduced some of the properties of the disordered peptides in solution,27,28 but underscore the computational and modeling difficulty of forming structures resembling fibrils. All-atom simulations conducted by Shea and co-workers give detailed insight into the monomer structure in dilute solution and in vacuo.13,14 In a set of all-atom molecular dynamics simulations with explicit water representation, Hummer and coworkers demonstrate that with incomplete NMR data from Tycko and co-workers, a set of four related but distinct minimum fibril models consistent with the NMR restraints are all structurally stable for at least a few nanoseconds.21 All-atom simulation of the full-length Aβ peptide aggregation is likely difficult due to the extremely long experimental timescales (hours to days, depending on conditions) and large system sizes (about ten peptides of 40 amino acid residues) necessary for fibril formation.

We have recently developed a new coarse-grained protein model that is a greatly enhanced version of coarse-grained models we have used in studying protein folding and non-disease protein aggregation.29-34 The new model, described in Methods, has been validated on folding thermodynamics and kinetics for proteins L and G, and provides higher structural resolutions (∼3.0 Å Cα RMSD) of the folded state relative to our old model, especially for descriptions of β-sheets (E.-H. Y., N.L.F. and T.H.-G., unpublished results). We use this new model for the first time to simulate Aβ1−40 oligomerization in order to address three primary questions regarding the association of Aβ1−40 peptides into fibrils.

First, what is the number of peptides involved in the critical nucleus for subsequent fibril elongation and does it differ among quaternary forms? Starting from a mature fibril structure composed of 40 chains, we systematically shorten the protofibril and measure structural stability over an equilibrium ensemble for each n-chain oligomer for each quaternary form. By calculating the equilibrium populations of structurally stable and unstable protofibrils, we determine the shift in population dominated by free monomer to the ordered protofibril to quantify free energy profiles for our model (Figure 3). On the basis of this thermodynamic analysis, we determine that the barrier in free energy occurs at a critical nucleus value of ten chains for both quaternary C2x and C2z forms.

Second, given the hypothesis of a nucleation-dependent polymerization mechanism, and NMR guidance as to the structure of the monomer in the mature fibril,16,17,19 what is the minimum number of chains in an ordered oligomer necessary for assembly of a structurally stable protofibril? The commonly assumed nucleation-dependent polymerization (Figure 3) suggests that beyond the critical nucleus size there is a minimum stable protofibril that reaches a constant ΔΔG for subsequent monomer addition, and thus initiates the behavior of a long fibril. We find that this constant addition free energy regime is evident from the thermodynamic analysis of our model, and determine that mature fibril behavior is reached at ∼16 chains. We show that the constant free energy for monomer addition correlates with a plateau in the hydrophobic residue density that, in turn, correlates with structural C2z order and stability by decreasing the likelihood of losing hydrophobic interactions due to fibril subunit rotation.

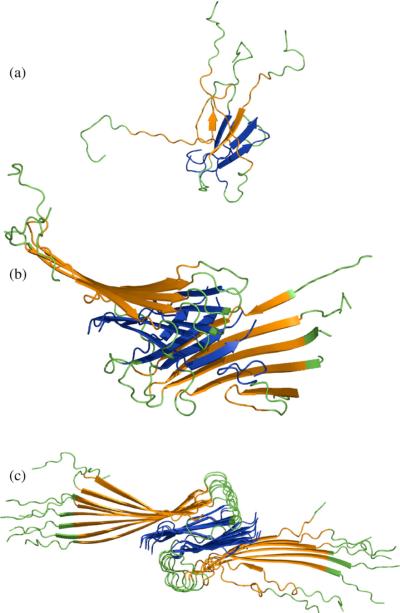

Finally, what is the fibril elongation mechanism of Aβ1−40 and the two quaternary structures? We find that the C2z form shows a greater ratio of correct parallel N termini addition to incorrect antiparallel addition relative to the C2x quaternary structure. We attribute this difference in elongation between the two quaternary forms as arising from differences in structure at the fibril ends due to the consequences of stagger in the interdigitation of the N-terminal and C-terminal β–strands. We find that the C2z form exhibits a structural asymmetry in the fibril seed ends, with one side exposing the N-terminal region while the other side exposes the C-terminal region, while the fibril ends for the C2x quaternary structure are not structurally distinguishable. This interdigitation and interplay with quaternary structure suggest unidirectional growth of the protofibril for the C2z quaternary form, while we expect bidirectional growth for C2x on the basis of our model. We show that mixed stagger forms (+N on one half of the fibril and −N on the other half) reverse the end symmetries of the C2x and C2z quaternary forms, leading to potentially different mature fibril morphologies.

Results

Symmetry of fibril ends for different quaternary forms

To examine the effect of stagger on the fibril quaternary structures, we built model structures for both IC2x and C2z symmetries for internal stagger values of −2, −1, +1 and +2 (Figure 2). When the C2x models are constructed with any pure stagger and examined as a two-monomer cross-section (down the fibril axis), one monomer has a protruding C-terminal strand, while the paired monomer has a protruding N-terminal strand (Figure 4). Although the resulting C2x protofibril has only approximate C2 symmetry around the fibril axis, due to imperfect interdigitation of the residues involved in the C-terminal hydrophobic interface,16 the resulting C2x fibril ends are nearly indistinguishable (Figure 4). When fibrils with C2z symmetry are constructed with any pure stagger, there is more perfect C2 symmetry around the fibril axis relative to C2x; however, when examined in cross-section, the ends are distinguishable. For the case of C2z fibrils, one end has both monomers presenting a protruding N-terminal strand, while the alternate end has both monomers exhibiting a protruding C-terminal strand (Figure 4). If instead we construct a C2z fibril with a mixed stagger: i.e. a +1 stagger for one of the fibril halves and a −1 stagger for the other, the resulting C2z fibril structure shows symmetric ends, while the C2x fibril shows asymmetric ends. We note that the known solid-state NMR constraints do not preclude the possibility of a mixed stagger. In what follows, we label the two ends as A or B to examine the consequences of symmetry or asymmetry of ends on structural stability, and mechanism and rates of fibril growth in our models.

Figure 4.

Effect of internal stagger on terminating ends of fibril. A schematic of 16 chain C2x and C2z fibrils are shown for internal staggers STAG (−1), STAG (+1) and mixed STAG (+1/−1) with the N-terminal region colored teal and the C-terminal region colored orange. STAG (−1) C2x has superimposable, symmetric ends. End A can be approximately superimposed on end B by a simple rotation of 180° about the x-axis (hence C2x). STAG (−1) C2z has distinct, asymmetric ends. End A exposes the C-terminal β-strands, and end B exposes the N-terminal β-strands. Ends A and B of the C2z fibril cannot be superimposed on end A by any rotation. C2x STAG (+1), like C2x STAG (−1), has superimposable, symmetric ends. C2z STAG (+1), like C2z STAG (−1) above it, has distinct, asymmetric ends. C2x STAG (−1/+1) has the top peptide STAG (+1) and bottom peptide STAG (−1). Mixing staggers in C2x de-symmetrizes the C2x ends. Mixing staggers in C2z symmetrizes the C2z ends, so that each end has one subunit with an exposed N-terminal β-strand, and the other with an exposed C-terminal β-strand, unlike the two asymmetric ends in “pure” C2z STAG (−1) or C2z STAG (+1) models.

Structural stability and identification of critical nucleus

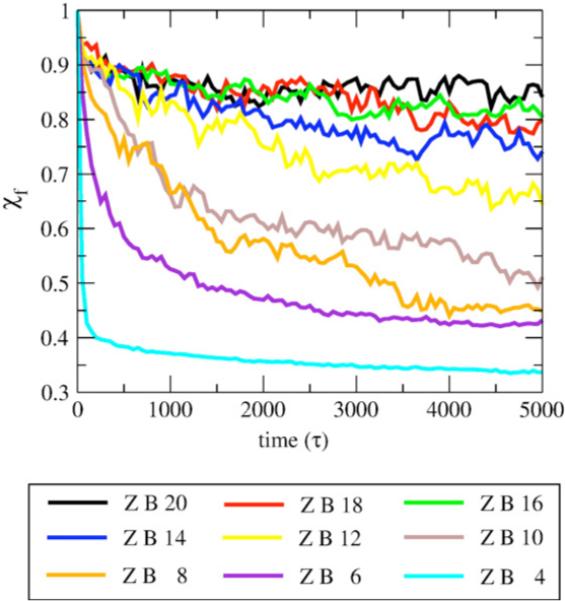

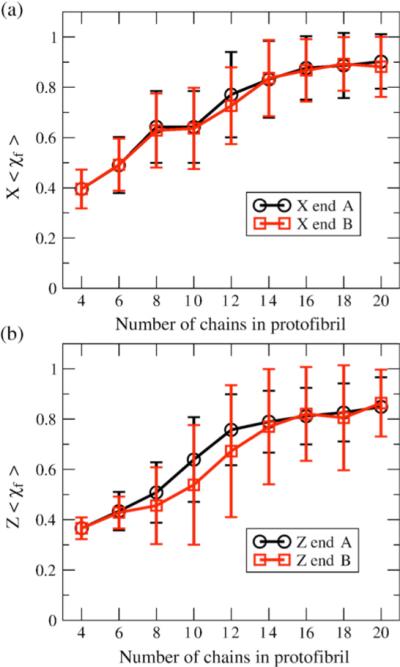

We next investigate the structural stability of fibril seed models for different seed sizes for both the C2x and C2z forms by simulating their dynamics at a constant temperature of T* = 0.45 (T≈337 K), and monitoring the amount of fibril order as a function of time. As a measure of fibril order, we define a structural similarity parameter, χf, which measures the fraction of residue pair-distances retained in the β-sheet regions, and restricted to the two exterior chains on each end of the protofibril structure and their two neighboring chains (see Methods for the definition of χf). The χf metrics allow a direct comparison between structures of different numbers of chains, since only the exposed and subsequent layer are included, so that changes in the metric versus number of chains is not simply due to the slower dynamics of a larger fibril seed. Since this metric includes contacts at the C-terminal interface between the subunits, it is sensitive to translation and rotation of one subunit with respect to the other (perpendicular to the fibril axis), and thus measures disorder of the quaternary structure. Due to asymmetries in structure of the exposed ends depending on quaternary symmetry, we measure the structural integrity of the A and B exposed ends of the fibril separately (Figure 4).

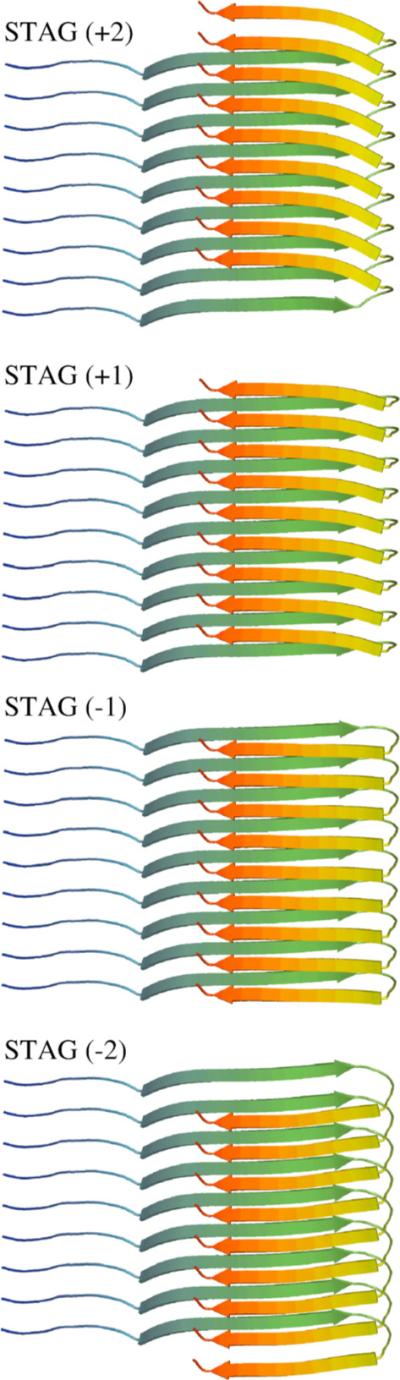

We simulate protofibrils with cross-sections composed of two U-shaped monomers, ranging in number between four and 20 chains, as shown in Figure 1, and observe changes to the structural integrity of the fibril seeds by monitoring χf. In Figure 5, we show the time-course of χf for different structured oligomer sizes, and Figure 6 plots the average of this metric for the last 500 τ of simulation time, <χf>, versus number of chains, for the two quaternary forms. The χf and <χf> trends with increasing oligomer size show increasing quaternary order due to a decrease in motion of one side of the fibril relative to the other, and thus providing greater stabilization of fibril ends. We note that at ∼16 chains for both the C2x and the C2z form, χf and <χf> saturates.

Figure 5.

Time-course for protofibril stability measured by χf. The metric χf measures the pair distances between the residues on both sides of the fibril, and is more sensitive to rotation of one subunit with respect to the other, and thus measures fibril disorder of the quaternary structure. The time-course data averaged over all trajectories of C2z fibrils for lengths four to 20 chains for fibril end B.

Figure 6.

Protofibril stability measured by <χf> versus number of chains; <Χf> is an average measure of the fibril order of the edge chains for stable quaternary structure for (a) C2x form and (b) C2z for the two ends of the protofibril: end A (black) and end B (red). Note the difference between the two distinguishable ends of the C2z oligomers due to stagger effects. The error bars represent standard deviation.

Based on the ensemble composed of the final structures of each of the trajectories for a given oligomer size, n, we calculate equilibrium populations of structurally stable and unstable protofibrils based on a χf cutoff value of 0.7. The fraction of trajectories that correspond to χf >0.7 measures a population, Cn, of n-ordered monomers in a protofibril or seed with intact end monomers. This population is in equilibrium with the remaining fraction of trajectories corresponding to a protofibril with loss of structural order of one monomer end, and thus measures the population Cn–1. On the basis of thermodynamic arguments advanced by Ferrone for nucleation-polymerization reactions relevant for aggregation kinetics,23 at equilibrium we can estimate the change in free energy, ΔG, per unit monomer as:

| (1) |

where n is half the number of monomers and integration over all oligomer sizes allows us to generate a free energy curve like that in Figure 3 based on Cn and Cn–1 populations measured in our model.

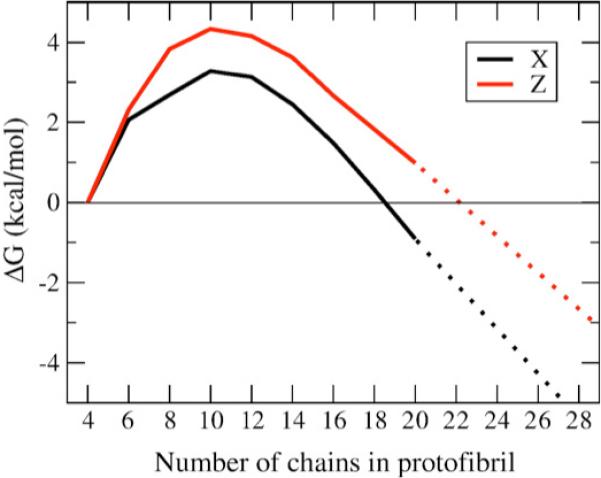

Table 1 gives the populations of Cn and Cn–1 and Figure 7 plots calculated free energies as a function of oligomer size, and as a function of quaternary symmetry. It is evident that the critical nucleus size is ten chains for both the C2z and C2x quaternary structures. Below that number of chains there is a free energy barrier to association into ordered oligomer chains, and thus the equilibrium shifts in favor of the free monomer. At ∼16 chains and above, consistent with the averaged time-course data in Figure 6, the oligomer does not lose overall fibril structure, and now reaches a constant free energy gain for addition of new monomers to the ordered protofibril (Figure 7).

Table 1.

Equilibrium populations of ordered fibrils, Cn and populations with free monomer, Cn−1, and calculated changes in free energy, ΔG, per unit monomer based on equation (1)

| C2x symmetry |

C2z symmetry |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of chains, n | Cn | Cn−1 | dΔG/dn | Cn | Cn−1 | dΔG/dn |

| 4 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | – | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | – |

| 6 | 0.0312 | 0.9688 | 2.060 | 0.0208 | 0.9792 | 2.310 |

| 8 | 0.2604 | 0.7396 | 0.626 | 0.0729 | 0.9271 | 1.526 |

| 10 | 0.2708 | 0.7292 | 0.594 | 0.3028 | 0.6972 | 0.500 |

| 12 | 0.5625 | 0.4375 | −0.151 | 0.5729 | 0.4271 | −0.176 |

| 14 | 0.7569 | 0.2431 | −0.682 | 0.7083 | 0.2917 | −0.532 |

| 16 | 0.8333 | 0.1667 | −0.966 | 0.8333 | 0.1667 | −0.966 |

| 18 | 0.8750 | 0.1250 | −1.168 | 0.8021 | 0.1979 | −0.840 |

| 20 | 0.8854 | 0.1149 | −1.227 | 0.8021 | 0.1979 | −0.840 |

Figure 7.

Free energy profile for free monomer and protofibril equilibrium. The free energy versus number of ordered chains in an oligomer is plotted for C2x (X, black) and C2z forms. The free energy shows a clear maximum at ten chains for C2z and ten to 12 chains for C2x, indicating the region of the critical nucleus. A constant, negative slope at ∼16 chains and above is indicative of reaching a stable fibril regime.

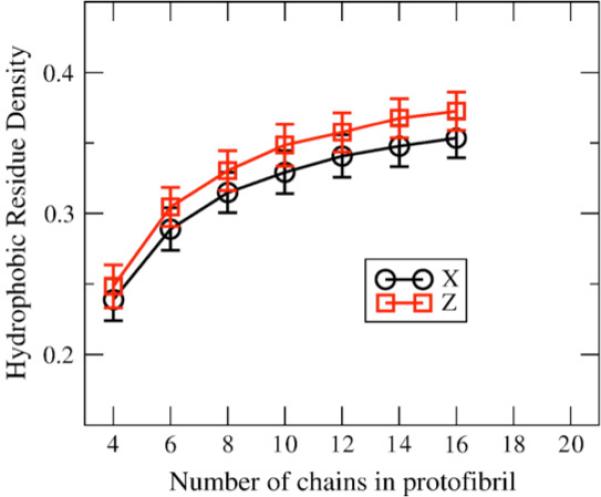

The underlying molecular explanation for the increasing stability of a quaternary assembly up to ∼16 monomer chains, and the constant free energy gain for subsequently larger protofibrils, is evident by evaluating the hydrophobic residue density of the starting structures at each seed size and each symmetry. Because hydrophobic interactions are thought to stabilize amyloid fibril structures, once a fibril reaches a certain length, the average hydrophobic residue density should be a constant. To test this hypothesis, the hydrophobic residue density of the core of the equilibrated starting structures was measured by calculating the number of large hydrophobic residues (see Methods) within 2.0 units (7.6 Å) of the tagged residue (excluding first and second neighbors on the same peptide) divided by the volume, averaged over residues 29−40 and over all the peptides in the structure.

Figure 8 plots the average hydrophobic residue density versus the number of chains in the oligomer for both symmetries. The average hydrophobic density correlates with the stability of the oligomers in Figures 5 and 6, and the linear regime of free energy once past the critical nucleus in Figure 7; as the oligomers get larger, the stability and hydrophobic density increase up until ∼16 chains, where both the structural stability and hydrophobic density level off. It is of note that C2x and C2z forms do not show strikingly different stabilities in this analysis, meaning that they are both reasonable fibril quaternary structures, similar to what was found by short all-atom simulation of eight chain structures.21

Figure 8.

Hydrophobic residue density versus number of chains. Hydrophobic density (number of hydrophobic residues per unit volume) versus number of chains for the C2x and C2z forms after initial equilibration. The error bars represent standard deviation for the 24 structures created from the 40 chain equilibration runs. The hydrophobic density for C2z is higher than C2x for all oligomer sizes.

Fibril elongation studies

Since the lag time for forming amyloid fibril for Aβ1−40 takes as much as a few days in the laboratory, even coarse-grained simulations of fibril formation from entirely disordered peptides may be intractable. Seeding a solution of Aβ1−40 with fragments of pre-formed Aβ1−40 fibrils, however, skips the lag phase, and experiment shows that fibril formation proceeds rapidly relative to the unseeded experiments.17 Although orders of magnitude faster than the lag time in fibril formation, fibril elongation is still a slow process relative to simulation time-scales. Goto and co-workers recently measured a sustained rate of amyloid fibril elongation to be 200 nm/min, which corresponds approximately to 70 ms per monomer incorporated into the fibril.35

Nonetheless, simulations that incorporate unstructured monomers into protofibril seeds should be more tractable than forming the fibrils from disordered monomers. The ability to propagate the elongation of the fibril through the addition of free monomers is a minimum necessary condition to show that the physics of the model represent the relatively fast fibril formation of the Aβ1−40 system in seeding experiments. This simulation also enables another comparison of the C2x and C2z quaternary structures, because the ability of the structure to propagate by elongation could be a criterion to determine which of the two structures is the most likely formed in vitro and perhaps in vivo; a structure that does not elongate will not be the structure that forms the amyloid fibrils measurable by solid-state NMR.

The equilibrated 16-chain fibrils from the stability runs were used as seeds for fibril elongation simulations, since on the basis of the results described in the previous section this oligomer size should be acting as a proper protofibril. Typical seeded fibril kinetics experiments for Aβ1−40 use a peptide concentration of the order of 100 μM,17,35 equivalent to one peptide for a simulation box 270 Å on a side. Simulating a system at that dilution would require a significant amount of computational time devoted entirely to diffusion of peptides towards the seed. To focus our study on the elongation of fibrils, our simulation conditions comprised of two equilibrated Aβ1−40 peptides that are placed randomly and uniformly on the surface of a sphere with the origin at the center of the fibril end, defined as the midpoint on the line connecting the 33rd bead on the two exterior fibril peptides. The two peptides, one at each end of the fibril, were placed so that amino acid 20 was five units (19 Å) from the center of the fibril end, and configurations where the peptide overlapped with the seed were excluded. Given the large seed size used here, the two peptides placed at opposite ends of the fibril rarely interact with each other. This procedure was the same for C2x and C2z symmetry forms. From ∼2000 of these prepared starting structures, each was simulated for 1000τ (200,000 time-steps) at T* = 0.45.

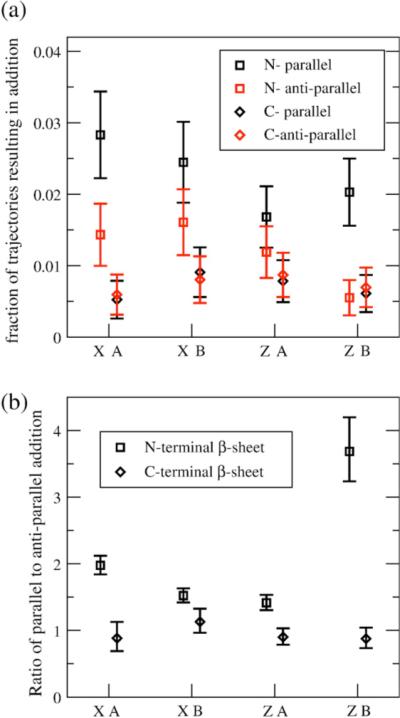

The number of trajectories resulting in the formation of partial (three or more amino acid residues with formed hydrogen bonds) parallel additions in the N-terminal and C-terminal β-sheet regions of the fibril seed, and “incorrect” antiparallel additions to the fibril seed was then calculated. In this analysis, all parallel additions within the β-sheet regions are summed, even if they are not fully in register, though in-register parallel additions made up on average 75% of all parallel additions. (The data were analyzed also with out-of-register parallel additions either ignored or added to “incorrect” additions; the conclusions remained the same.) Simulations resulting in both N-terminal and C-terminal in-register parallel addition did occur, but made up <0.5% of the population, making comparison between symmetries difficult. An example of an addition demonstrating both N-terminal and C-terminal addition is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Example addition to fibril seed by free peptide. A peptide (yellow) with a random initial configuration without contacts with the seed is shown with partial in-register parallel addition to both N-terminal and C-terminal β-sheets of the fibril seed.

The fractions of simulations resulting in an addition of the C-terminal β-strand region of a random peptide to the protofibril seed is summarized in Figure 9(a). Both C2x and C2z forms of the seed are capable of propagating monomer additions in correct parallel arrangements to both the N-terminal and C-terminal sheets on both ends of the fibril, though the amount of parallel N-terminal additions is greater than the amount of C-terminal additions for all symmetries and end combinations. Similarly, both forms have some percentage of trajectories (∼0.5− 1% for C-terminal and 0.5−1.5% for N-terminal) that result in antiparallel or incorrect additions that will result in lengthening the time-scale for extending a stable fibril structure, since the incorrect addition will have to be “annealed out” before the fibril can continue to grow. The greatest distinction between the fibrils can be seen in Figure 9(b), which plots the ratio of the parallel to antiparallel additions, depending on at which end of the fibril the additions occur. Though the addition to the C-terminal β-sheet for each symmetry and fibril end combination is similar, the B end of the C2z form shows almost four times the amount of N-terminal parallel addition versus antiparallel addition, approximately twice as much as any other combination of symmetry and end. Unlike the stability of the fibril ends, this addition metric distinguishes the C2x and C2z forms, and demonstrates that monomer addition to amyloid fibrils may result in unidirectional or uneven growth from the fibril ends for C2z, while we expect bidirectional growth for C2x based on the results of our model shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Monomer additions to protofibrils for C2x and C2z fibrils. (a) Fraction of trajectories resulting in partial parallel (black) and antiparallel (red) additions to the N-terminal (□) and C-terminal (◇) β-sheets. The error bars represent standard deviation approximated from distributions with binary outcomes. (b) Ratio of partial parallel to antiparallel additions to the N-terminal (□) and C-terminal (◇) β-sheets. The error bars are the 95% confidence interval for “relative risk” measure comparing binary outcomes.

The differences among quaternary symmetries and the possibility of unidirectional growth most likely arises from the effects of internal stagger that Tycko and co-workers have suggested for Aβ1−40 based on the isotopic dilution experiments16 and shown in Figures 2 and 4. We find that there is a different type of local symmetry splitting between the C2x and C2z forms, like the experimental models involving +N or −N staggers, but we have shown that there is important local symmetry splitting in the exposed protofibril ends of the two proposed quaternary structures (Figure 4). We suggest that the end of the C2z fibril with exposed N-terminal regions is better able to nucleate in-register parallel additions than the C-terminal exposed region, because the hydrophobic, hydrophilic, and aromatic residue patterning in N-terminal residues 17−21 is accessible to the free peptide without non-specific hydrophobic interactions with the C-terminal hydrophobic cluster. A free peptide approaching the exposed N-terminal region has more favorable interactions, encouraging an in-register parallel addition; an antiparallel arrangement does not result in as much favorable enthalpy (interchain hydrophobic interactions) for the same entropic cost (peptide backbone entropy), and therefore occurs relatively less frequently. When the N-terminal hydrophobic cluster of a free peptide approaches the end of a fibril with a buried N-terminal region and exposed C-terminal residues, the patterning of amino acid residues on the C terminus is more generic, so that both parallel and antiparallel arrangements are equally likely.

We confirm this hypothesis by examining the parallel and antiparallel additions to the C2x fibril ends, which have one subunit with the N-terminal peptide exposed, and the other with the C-terminal peptide exposed. On both ends of the C2x fibril, the N-terminal exposed subunit has only ∼10% of the antiparallel additions to that end, while it has ∼25% of the parallel additions. We therefore suggest that the C2z end B, where both subunits have N-terminal exposed regions, has greater in-register parallel addition due to the internal stagger. We note also that >80% of the antiparallel additions have the antiparallel register of Aβ16−22 fibrils, indicating antiparallel β-sheet formation in this region, and exposing the limitations of the Aβ16−22 fragment for understanding fibril elongation mechanisms.

Discussion and Conclusions

We have used a coarse-grained protein model to simulate Aβ1−40 oligomers to determine both the critical nucleus and a minimum assembly of N monomer cross-sections of a mature fibril necessary for a structurally stable protofibril seed, and used that seed to measure fibril elongation propensities for different quaternary forms. Determining the critical nucleus as well as the minimum number of peptides necessary for a stable protofibril is an essential piece of information for experimentalists searching for signatures of these kinetic steps and the modeling of rate equations for aggregation kinetics, as well as theoreticians seeking to simulate a minimum size system capable of describing the structural properties of the mature fibril.

The first important conclusion of our study is to question the underlying assumption that the Aβ1−40 nucleation event is a sudden transition from isolated, disordered monomers to some minimal organization in either the monomer (i.e. a nucleated turn and/or β–strands) or intermolecular monomer–monomer interactions. Our approach instead works backward from an unambiguously ordered and stable protofibril with quaternary structure to see at what oligomer size the different levels of order break down. We find that the critical nucleus in our model corresponds to the loss of quaternary order, i.e. a loss of registry in orientation of the two fibril halves, that partially destabilizes edge chains through loss of hydrophobic contacts with the other fibril sub-unit (Figure 11(a)). Below the critical nucleus, the instability of edge chains is due to insufficient stabilization of inter monomer–monomer interactions within the same fibril half sub-unit as well (Figure 11(b)). In the linear regime of free energy represented by 16 chains (Figure 11(c)) quaternary order is well established and hence edge chain monomers are stabilized by ordered monomers in both fibril halves. This result implies a much greater level of structural order than is usually assumed for the smallest oligomer sizes, and seems consistent with the goals of a reductionist approach that seeks to determine whether structural order exists at the level of the monomer.14,15,36-38

Figure 11.

Comparing structural stability of example structures of varying length of oligomer. Representative oligomer structures after 5000τ constant temperature simulations depicting greater structural stability as number of chains increases. (a) Four-chain simulation shows a complete loss of fibril structure. (b) Ten-chain simulation shows that, although a significant fraction of intermolecular β-sheet is retained, the fibril subunits rotate with respect to one another, leading to disorder and loss of contacts in the edge chains. (c) The 16-chain simulations show retention of fibril order, and a clear fibril axis.

This method of working backward from known order to disorder leads naturally to a means for determining free energy trends in nucleation-polymerization mechanisms to find a critical nucleus size within our model. On the basis of equilibrium ensemble populations for a given proposed protofibril size, and analyzed with a fibril order metric χf, we can determine free energy barriers for nucleation of the thermodynamically scarce species that shifts the equilibrium from free monomer to stable, and therefore polymerizable, protofibril. We find a critical nucleus size of ten chains, which is in pleasing agreement with the results reported by Teplow and co-workers, who showed that kinetic models of amyloid formation fit time-course data when the number of chains involved in the aggregation nucleus for Aβ aggregation is set to ten chains.10 Below this critical nucleus, the edge chains of the four, six, and eight chain protofibril structure are unstable, shifting the population from ordered fibril, Cn to populations with increased free monomer Cn–1. The true protofibril state, i.e. the minimum size of protofibril capable of elongation, is ∼16 chains, and subsequent additions of monomers involve a constant gain in free energy that is insensitive to the number of interior chains.

Beyond this minimum stable seed size, adding chains to the protofibril does not increase the stability of the outermost chains, which we have shown correlates with a leveling off of the hydrophobic residue density and helps to compensate for the unfavorable entropy of ordering the monomers in the sub-unit halves as well as the two subunit halves with respect to each other. This is an intuitive result, because the hydrophobic interactions are thought to stabilize amyloid fibril structures and, once a fibril reaches a certain length, the average hydrophobic residue density should be a constant. Hecht and co-workers have demonstrated that the two additional hydrophobic residues (isoleucine and alanine) at the C terminus of Aβ1−42 are responsible for the increased fibril-forming propensity of Aβ1−42 compared with that of Aβ1−40.8 These additional hydrophobic residues would shift the plateau of hydrophobic density to smaller oligomer sizes for Aβ1−42. In turn, we hypothesize that there is a corresponding shift in the size of a viable seed for fibril formation in vitro to smaller numbers of chains relative to Aβ1−40,6-8,39 which may be correlated with greater disease virulence in vivo39-41 of the Aβ1−42 versus Aβ1−40 sequences. The calculation of hydrophobic density therefore may be predictive for the size of critical nucleus and/or protofibril regime for any new Aβ fragment or mutation, or other systems that assemble into fibrils in their aggregated state.

For proposed fibril models with no quaternary structure, such as that suggested by Lührs et al.42 for methionine sulfoxide 35 (Met35ox) mutants of Aβ1−42, the χf metric will overestimate the critical nucleus size, since it is sensitive to quaternary disorder due to rotations of the fibril halves. However, for a protofibril with a cross-section of one peptide, only half the number of chains would be necessary to reach the plateau in hydrophobic density compared to a protofibril with a two peptide cross-section, since the hydrophobic density of all the peptides in the protofibril are now averaged over a single subunit. Thus, for any Aβ system that does not form quaternary structure, we would predict a reduction in the size of the critical nucleus and protofibril capable of elongation relative to Aβ1−40, although the height of the free energy barrier may be greater. However, whether the Met35ox mutant is a good model for Aβ1−42 is open to question, since the oxidized methionine residue is a disruptive mutation for stabilizing the hydrophobic interface of the two halves of the quaternary structure. Thus, the best model for wild-type Aβ1−42 likely remains one in which some type of quaternary structure is present as it is for Aβ1−40.

The number of chains where the free-energy for addition of another monomer becomes constant corresponds to the point of minimum protofibril size where the edges and quaternary structure are stable and behave like a long fibril. In our model, this point corresponds to ∼16 chains, which we use for characterizing the propensity to add additional monomers to understand polymerization in more molecular detail and to compare different quaternary forms. Based on our simulations, which quantify parallel additions and “incorrect” antiparallel additions for both fibril seed ends, both C2x and C2z are capable of elongation. However, we suggest that C2z may be the dominant amyloid fibril form, because it can more readily propagate by in-register parallel addition with a much lower “error” through antiparallel additions. The most recent NMR studies have suggested that the quaternary structure of one particular fibril of Aβ1−40 involves the C2z form.16

One possible reason for this preference for C2z over C2x most likely arises from a topological “frustration” for addition to C2x. In the C2x form, the C-terminal β-strands of the peptides in both subunits are parallel; the same is true for the C2x N-terminal β-sheets in both subunits. In contrast, the N-terminal (and C-terminal) β-strands are antiparallel in the C2z form. If the C terminus of a free peptide approaches the C2x form fibril in an orientation antiparallel to the C terminus of one of the edge peptides (i.e. in a direction not suitable for extending the in-register parallel structure of the fibril), the free peptide is similarly antiparallel to the C terminus of the other exposed fibril peptide. In this case, it must break any favorable interactions (i.e. hydrophobic clustering) and flip orientation in order to continue the correct fibril elongation. For the C2z form fibril, conversely, if a free peptide approaches in a configuration antiparallel to one of the fibril peptides, it is parallel with the other exposed fibril peptide terminus and can form in-register parallel β-sheet contacts with the appropriately oriented exposed fibril peptides, thus incorporating the free peptide into the fibril. However, our simulations are much too short to observe the multiple binding and unbinding events that would be necessary to demonstrate that this mechanism contributes to the difference in additions between C2x and C2z.

We have concluded from our simulation data that it is the structural consequences of the internal stagger16 that results in higher rates of in-register parallel addition and, more importantly, on fewer growth-halting antiparallel additions for the C2z fibril with distinct ends. This opens up the possibility for unidirectional growth of the protofibril for this quaternary form, while we expect bidirectional growth for C2x on the basis of our model. Although NMR experiments support a +2 or −2 stagger, our model naturally equilibrates to a different STAG value of–1, and analysis of the NMR data for Aβ1−40 does not rule out the possibility of a mixed stagger, i.e. +N interdigitation for one fibril subunit half and −N interdigitation for the other fibril subunit. Model building shows that a mixed stagger quaternary structure for the C2z form symmetrizes the fibril ends, while it results in end asymmetry of the C2x form (Figure 4), thereby reversing the structural end symmetries of the two quaternary forms and potentially their elongation mechanism.

Although our model and experiment show both C2z and C2x are viable quaternary structures, and that mixed staggers are theoretically possible, we advance the much more speculative conclusion that macroscopic morphology differences in the mature fiber may be due to different quaternary and stagger configurations that affect directionality in fibril growth. We note that Aβ1−40 is known to form fibrils of at least two distinct architectures,18 which may be accounted for by distinct staggers and quaternary forms. Finally, we end the discussion by noting that the finite length of our simulation times makes the absolute percentages of any type of monomer addition rather low (∼3%), although it may increase with longer simulation runs. However, it raises the question of whether the Aβ monomer is the dominant unit for fibril elongation. One direction we will pursue is whether small oligomers are more viable addition units for fibril elongation, which has been suggested by Kayed and coworkers.43

Methods

The coarse-grained protein model

The three-flavor coarse-grained model we developed has been used to study the folding and aggregation propensities of members of the ubiquitin α/β fold class.29-34 We have recently updated the minimalist model to improve the faithfulness to real proteins while retaining its simplicity, which we describe here.

To better discriminate between hydrophobic residues of different sizes, we have updated the model to allow four flavors, consisting of large hydrophobic, small hydrophobic, neutral/small hydrophilic, and large hydrophilic, designated B, V, N, and L, respectively. The amino acid sequence of the Aβ peptide was mapped to its four-flavor sequence using the mapping shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mapping the 20-letter (20) amino acid code to the coarse-grained four-letter code (4)

| Letter code | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 4 | 20 | 4 | 20 | 4 | 20 | 4 |

| Trp | B | Met | B | Gly | N | Glu | L |

| Cys | B | Tyr | B | Ser | N | Asp | L |

| Leu | B | Val | V | Thr | N | Gln | L |

| Ile | B | Ala | V | Lys | N | Asn | L |

| Phe | B | Pro | N | His | N | Arg | L |

The Hamiltonian governing the interactions in the system is given by:

| (2) |

where θ is the bond angle, ϕ is the dihedral angle formed by four consecutive Cα positions, and rij is the distance between beads i and j. εH sets the energy scale and gives the strength of the large (B) hydrophobic contact. The bond angle term is a stiff harmonic potential with a force constant of kθ = 20 εH /rad2, and the optimal bond angle θ0 is set to 105°. Each dihedral angle in the chain is designated to be either structured (S), a weighted sum of helical and extended potentials, or turn (T) placed primarily in regions of the peptide containing glycine to account for the greater backbone mobility. The parameters A, B, C, and D are chosen to produce the desired minima (see Table 3), and ϕ0 is set to 0.17 for the helical portion of the helical (H) portion of the S potential and to −0.35 for the extended (E) portion (see Table 3). The k parameter is set to 1 for all dihedral potentials in this study.

Table 3.

Parameters for dihedral types

| Dihedral type | A (εH) | B (εH) | C (εH) | D (εH) | ϕ0 (rad) | Local minimaa (deg.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3* H | 0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | +0.17 | −65°, +50°, 165° | |

|

(helical) | ||||||

| 0.75* E | 0.9 | 0 | 1.2 | 0 | −0.35 | −160°, −45°, +85° | |

| (extended) | |||||||

| T | Turn | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | −60°, +60°, +180° |

Global minima are in bold.

The third term in equation (2) represents non-bonded interactions, and is determined according to the bead flavors B, V, N and L: S1 = 1.2 and S2 = 1 for B–B interactions; S1 = 0.6 and S2 = 0.5 for all V–V and V–B interactions; S1 = 2/5 and S2 =−1 for L–L, L–V and L–B interactions; S1 = 1.2 and S2 = 0 for all N–X interactions. Of the possible interaction combinations, attractive potentials result for interactions between hydrophobic beads (B–B, V–B and V–V interactions). The interactions among all other combinations of beads are repulsive, although the form of repulsion depends on the bead types involved. The sum of van der Waals radii σ is set at 1.095 to mimic the large excluded volume of amino acid side-chains. This term is evaluated for all bead pairs within a distance cutoff of 5.5 units (21 Å).

The last term in equation (2) describes a direction-dependent hydrogen bond interaction to better represent the interactions that form and stabilize β-sheets and α-helices. The functional form is inspired by the Mercedes Benz (MB) model of water, introduced by Ben-Naim44 and further developed by Dill and co-workers.45 The hydrogen bond potential between two residues i and j is given by:

| (3) |

where:

| (3a) |

| (3b) |

| (3c) |

The hydrogen bond strength is modulated by the value εHB, and is set at 1.6εH. The distance-dependent term F is a Gaussian function centered at the ideal hydrogen bond distance rHB, set to 1.125 in accordance with our survey of PDB structures. For the direction-dependent terms G and H, we use a modified exponential instead of a Gaussian function to smoothen the potential energy surface. The vectors tHB,i and tHB,j are unit normal vectors for the planes described by (i–1, i, i+1) and (j–1, j, j+1) respectively, and uij is the unit vector between residues i and j. The width of functions F, G and H are set by σHBdist = 0.5 and σHB = 0.45. The hydrogen bond potential is evaluated for all i–j bead-pairs within a cutoff distance of 3.0 units.

Model building

A model of an amyloid fibril building block was constructed in single-bead representation according to the constraints specified by Petkova et al.19 The 20-letter sequence of the Aβ1−40 peptide and the corresponding coarse-grained (CG) primary and secondary structure is:

primary sequence DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQKLVFFAEDVGSNKGAIIGLMVGGVV

primary sequence (CG) LVLBLNLNNBLVNNLNBVBBVLLVNNLNNVBBNBBVNNVV

secondary structure (CG) SSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSTTSSTTSSSSSSSTT

To construct the amyloid fibril building-block, in-register parallel intermolecular β-sheet models were made with 40 starting chains, one for the C2x and one for the C2z form. Each strand in the models contains a disordered N-terminal region (residues 1−9), an N-terminal β-sheet region (residues 10−24), a turn region (residues 25−29), and a C-terminal β-sheet region (residues 30−40). In comparison to the model of a fibril presented by Petkova et al., we have the C-terminal β-strand “flipped” in orientation, where the residues packed against the N-terminal β-strand are even-numbered, as determined by the most recent NMR data.16 Models were built with N-terminal and C-terminal strands without stagger, but interdigitation of structures into staggered structures can be seen in equilibrated structures at finite temperature.

Two possible conformers of the amyloid fibril were built. Given that z is defined as the fibril axis and x as the direction of the β-strands, fibril models with approximate C2 symmetry around each of these axes, named C2z and C2x, respectively, were constructed. Models for each different seed size (4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20) were created by retaining the innermost chains from the equilibrated 40 chain seed starting structures of the two symmetries. The outermost chains were discarded to ensure that edge effects (loss of perfect fibrillar order of the exterior chains) were not incorporated into the seeds. Once equilibrated, the beads representing the N-terminal and C terminal β-sheets interdigitate to form contacts internal to each subunit of the fibril with a particular value of “stagger”, as shown in Figure 2. The most recent solid-state NMR work has suggested that the stagger is either STAG (+2) or STAG (−2), although our models under thermal equilibration give STAG (−1).

Simulation protocol

We use constant-temperature Langevin dynamics with friction parameter ζ = 0.05. Bond lengths are held rigid by using the RATTLE algorithm.46 All simulations are performed in reduced units, with mass m, energy εH, and kB all set equal to unity. The 40 chain C2x and C2z fibril models were equilibrated with Langevin dynamics at a temperature of 0.45 for 1500τ (300,000 steps). This procedure was repeated 24 times so that the stochastic dynamics generated 24 equilibrated starting structures of a 40 chain fibril seed for C2x and C2z. Three to five simulations of each of 24 models of each symmetry were run for 5000τ (1,000,000 steps) at T*=0.45 (T≈337K). The reported protofibril stability data are based on statistics collected approximately 120 independent simulations per chain number and symmetry. Statistics on the chain conformation were gathered every 50τ (10,000 steps). Structural stability for each time-point was quantified by the χf parameter:

| (4) |

The metric is the sum over bead i on chain α and bead j on chain β (where i and j range from 17−21 and 30−34), and α and β range over the four chains making up the exterior and neighboring chains on each end), h is the Heaviside step function, ε is the tolerance set to 0.5 distance units (∼1.9 Å), is the distance between bead i on chain α and bead j on chain β, and is the pair distance in the initial structure, and M is a normalizing constant counting the total number of pairs (in this case it is equal to 600).

To investigate the addition of monomers to the protofibril seeds of different symmetries, monomer simulations decorrelated at high temperature (T*=1.0) and equilibrated at T*=0.45 as single chains (infinite dilution) were placed as described in the Results at the ends of equilibrated protofibrils of length 16 chains.

Molecular graphics

The molecular graphics were created in PyMOL†.

Acknowledgements

We thank Troy Cellmer and Harvey Blanch for useful discussion throughout this study, and Elizabeth Verschell for assistance with the coarse-grained force-field. We thank Robert Tycko for useful discussion and for the atomic coordinates for his models of Aβ1−40. We thank Kevin Kohlstedt, a DOE Computational Science Graduate Fellow, for careful reading of the manuscript during his internship at Berkeley Lab. N.L.F. thanks the Whitaker Foundation for a graduate research fellowship. Y.O. thanks the Guidant Foundation for a summer research fellowship. T.H.G. gratefully acknowledges a Schlumberger Fellowship while on sabbatical at Cambridge University. This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the NIH.

Abbreviation used

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

Footnotes

References

- 1.Dobson CM. Protein folding and misfolding. Nature. 2003;426:884–890. doi: 10.1038/nature02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobson CM. Principles of protein folding, misfolding and aggregation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;15:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bucciantini M, Giannoni E, Chiti F, Baroni F, Formigli L, Zurdo J, et al. Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding diseases. Nature. 2002;416:507–511. doi: 10.1038/416507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stefani M, Dobson CM. Protein aggregation and aggregate toxicity: new insights into protein folding, misfolding diseases and biological evolution. J. Mol. Med. 2003;81:678–699. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0464-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen FE, Kelly JW. Therapeutic approaches to protein-misfolding diseases. Nature. 2003;426:905–909. doi: 10.1038/nature02265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper JD, Lansbury PT., Jr Models of amyloid seeding in Alzheimer's disease and scrapie: mechanistic truths and physiological consequences of the time-dependent solubility of amyloid proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997;66:385–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarrett JT, Lansbury PT., Jr Seeding “one-dimensional crystallization” of amyloid: a pathogenic mechanism in Alzheimer's disease and scrapie? Cell. 1993;73:1055–1058. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim W, Hecht MH. Sequence determinants of enhanced amyloidogenicity of Alzheimer A {beta}42 peptide relative to A{beta}40. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:35069–35076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505763200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lomakin A, Chung DS, Benedek GB, Kirschner DA, Teplow DB. On the nucleation and growth of amyloid beta-protein fibrils: detection of nuclei and quantitation of rate constants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:1125–1129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lomakin A, Teplow DB, Kirschner DA, Benedek GB. Kinetic theory of fibrillogenesis of amyloid beta-protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:7942–7947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crescenzi O, Tomaselli S, Guerrini R, Salvadori S, D'Ursi AM, Temussi PA, Picone D. Solution structure of the Alzheimer amyloid beta-peptide (1−42) in an apolar microenvironment. Similarity with a virus fusion domain. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:5642–5648. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomaselli S, Esposito V, Vangone P, van Nul NA, Bonvin AM, Guerrini R, et al. The alpha-to-beta conformational transition of Alzheimer's Abeta-(1−42) peptide in aqueous media is reversible: a step by step conformational analysis suggests the location of beta conformation seeding. ChemBiochem. 2006;7:257–267. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumketner A, Bernstein SL, Wyttenbach T, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Bowers MT, Shea JE. Amyloid beta-protein monomer structure: a computational and experimental study. Protein Sci. 2006;15:420–428. doi: 10.1110/ps.051762406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernstein SL, Wyttenbach T, Baumketnert A, Shea JE, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Bowers MT. Amyloid beta-protein: monomer structure and early aggregation states of A beta 42 and its Pro(19) alloform. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2075–2084. doi: 10.1021/ja044531p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazo ND, Grant MA, Condron MC, Rigby AC, Teplow DB. On the nucleation of amyloid beta-protein monomer folding. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1581–1596. doi: 10.1110/ps.041292205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petkova AT, Yau WM, Tycko R. Experimental constraints on quaternary structure in Alzheimer's beta-amyloid fibrils. Biochemistry. 2006;45:498–512. doi: 10.1021/bi051952q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sciarretta KL, Gordon DJ, Petkova AT, Tycko R, Meredith SC. A beta 40-Lactam(D23/K28) models a conformation highly favorable for nucleation of amyloid. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6003–6014. doi: 10.1021/bi0474867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petkova AT, Leapman RD, Guo ZH, Yau WM, Mattson MP, Tycko R. Self-propagating, molecular-level polymorphism in Alzheimer's beta-amyloid fibrils. Science. 2005;307:262–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1105850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petkova AT, Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Delaglio F, Tycko R. A structural model for Alzheimer's beta-amyloid fibrils based on experimental constraints from solid state NMR. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:16742–16747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balbach JJ, Petkova AT, Oyler NA, Antzutkin ON, Gordon DJ, Meredith SC, Tycko R. Supramolecular structure in full-length Alzheimer's beta-amyloid fibrils: evidence for a parallel beta-sheet organization from solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1205–1216. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchete NV, Tycko R, Hummer G. Molecular dynamics simulations of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid protofilaments. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;353:804–821. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolphin GT, Dumy P, Garcia J. Control of amyloid beta-peptide protofibril formation by a designed template assembly. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2006;45:2699–2702. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrone F. Analysis of protein aggregation kinetics. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:256–274. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Favrin G, Irback A, Mohanty S. Oligomerization of amyloid A beta(16−22) peptides using hydrogen bonds and hydrophobicity forces. Biophys. J. 2004;87:3657–3664. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.046839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klimov DK, Straub JE, Thirumalai D. Aqueous urea solution destabilizes A beta(16−22) oligomers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:14760–14765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404570101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klimov DK, Thirumalai D. Dissecting the assembly of A beta(16−22) amyloid peptides into antiparallel beta sheets. Structure. 2003;11:295–307. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urbanc B, Cruz L, Ding F, Sammond D, Khare S, Buldyrev SV, et al. Molecular dynamics simulation of amyloid beta dimer formation. Biophys. J. 2004;87:2310–2321. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urbanc B, Cruz L, Yun S, Buldyrev SV, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Stanley HE. In silico study of amyloid beta-protein folding and oligomerization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:17345–17350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408153101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown S, Fawzi NJ, Head-Gordon T. Coarse-grained sequences for protein folding and design. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:10712–10717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1931882100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown S, Head-Gordon T. Intermediates and the folding of proteins L and G. Protein Sci. 2004;13:958–970. doi: 10.1110/ps.03316004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fawzi NL, Chubukov V, Clark LA, Brown S, Head-Gordon T. Influence of denatured and intermediate states of folding on protein aggregation. Protein Sci. 2005;14:993–1003. doi: 10.1110/ps.041177505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sorenson JM, Head-Gordon T. Matching simulation and experiment: a new simplified model for simulating protein folding. J. Comput. Biol. 2000;7:469–481. doi: 10.1089/106652700750050899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorenson JM, Head-Gordon T. Protein engineering study of protein L by simulation. J. Comput. Biol. 2002;9:35–54. doi: 10.1089/10665270252833181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sorenson JM, Head-Gordon T. Redesigning the hydrophobic core of a model beta-sheet protein: destabilizing traps through a threading approach. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 1999;37:582–591. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19991201)37:4<582::aid-prot9>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ban T, Hoshino M, Takahashi S, Hamada D, Hasegawa K, Naiki H, Goto Y. Direct observation of Abeta amyloid fibril growth and inhibition. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;344:757–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumketner A, Bernstein SL, Wyttenbach T, Bitan G, Teplow DB, Bowers MT, Shea JE. Amyloid beta-protein monomer structure: a computational and experimental study. Protein Sci. 2006;15:420–428. doi: 10.1110/ps.051762406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumketner A, Bernstein SL, Wyttenbach T, Lazo ND, Teplow DB, Bowers MT, Shea JE. Structure of the 21−30 fragment of amyloid beta-protein. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1239–1247. doi: 10.1110/ps.062076806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lazo N, Condron MM, Grant MA, Rigby AC, Teplow DB. Probing nucleation of Abeta monomer folding. Neurobiol. Aging. 2004;25:S149. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roher AE, Lowenson JD, Clarke S, Woods AS, Cotter RJ, Gowing E, Ball MJ. beta-Amyloid-(1−42) is a major component of cerebrovascular amyloid deposits: implications for the pathology of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:10836–10840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gravina SA, Ho L, Eckman CB, Long KE, Otvos L, Jr, Younkin LH, et al. Amyloid beta protein (A beta) in Alzheimer's disease brain. Biochemical and immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies specific for forms ending at A beta 40 or A beta 42(43). J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:7013–7016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Selkoe DJ. The molecular pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1991;6:487–498. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luhrs T, Ritter C, Adrian M, Riek-Loher D, Bohrmann B, Dobeli H, et al. 3D structure of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta(1−42) fibrils. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17342–17347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ben-Naim A. Statistical mechanics of water-like particles in 2 dimension. 1. Physical model and application of Percus-Yevick equation. J. Chem. Phys. 1971;54:3682–3695. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silverstein KAT, Haymet ADJ, Dill KA. A simple model of water and the hydrophobic effect. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:3166–3175. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersen HC. Rattle - a velocity version of the shake algorithm for molecular-dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Phys. 1983;52:24–34. [Google Scholar]