Abstract

The natural resting orientations of several species of nocturnal moth on tree trunks were recorded over a three-month period in eastern Ontario, Canada. Moths from certain genera exhibited resting orientation distributions that differed significantly from random, whereas others did not. In particular, Catocala spp. collectively tended to orient vertically, whereas subfamily Larentiinae representatives showed a variety of orientations that did not differ significantly from random. To understand why different moth species adopted different orientations, we presented human subjects with a computer-based detection task of finding and ‘attacking’ Catocala cerogama and Euphyia intermediata target images at different orientations when superimposed on images of sugar maple (Acer saccharum) trees. For both C. cerogama and E. intermediata, orientation had a significant effect on survivorship, although the effect was more pronounced in C. cerogama. When the tree background images were flipped horizontally the optimal orientation changed accordingly, indicating that the detection rates were dependent on the interaction between certain directional appearance features of the moth and its background. Collectively, our results suggest that the contrasting wing patterns of the moths are involved in background matching, and that the moths are able to improve their crypsis through appropriate behavioural orientation.

Keywords: disruptive coloration, background matching, camouflage, animal coloration, predation

1. Introduction

The best-known interrelated mechanisms through which coloration can act to reduce the detection rates of potential prey are background matching and disruptive coloration (Thayer 1909; Cott 1940; Kingsland 1978; Ruxton et al. 2004; Wilkinson & Sherratt 2008; Stevens & Merilaita 2009). With background matching, objects are difficult to detect simply due to their similarity to the background. Conversely, the striking/high-contrast markings involved in disruptive coloration create ‘the appearance of false edges and boundaries and hinders the detection or recognition of an object's, or part of an object's, true outline and shape’ (Stevens & Merilaita 2009).

In recent years, much effort has been directed at understanding the disruptive coloration principle and there is now considerable evidence that disruptive markings in prey items serve to reduce their detectability by predators (Merilaita 1998; Thomas et al. 2004; Cuthill et al. 2005; Merilaita & Lind 2005; Schaefer & Stobbe 2006; Stevens et al. 2006a,b; Fraser et al. 2007; Kelman et al. 2007). Many of these studies carefully controlled for background matching by altering only the position of the high-contrast elements of the objects of interest. However, in asking questions about disruptive coloration while directly controlling for background matching, one might get the impression that the two principles are readily separable (Stevens 2007). While disruptive coloration can operate successfully independent of background matching (Schaefer & Stobbe 2006), it seems that they are to an extent interdependent (Fraser et al. 2007; Stevens 2007), a stance adopted in Cott's (1940) landmark text on animal coloration: ‘…the effect of disruptive pattern is greatly strengthened when some of its components closely match the background…’. Here, we extend the research by demonstrating that contrasting wing markings (with seemingly, yet so far unproven, disruptive functions) within two groups of nocturnal moths can act to facilitate background matching. Moreover, we show that the effectiveness of the camouflage in these moths is enhanced by selection of appropriate resting orientations.

Much previous work has been done on artificial (Pietrewicz & Kamil 1977; Bond & Kamil 2002, 2006; Fraser et al. 2007) and natural (Sargent 1968; Sargent 1969a–d; Sargent & Keiper 1969; Endler 1984; Moss et al. 2006) moth crypsis, including several classical studies that have revealed the importance of orientation on crypsis. In particular, Pietrewicz & Kamil (1977) explored the effect of body orientation in Catocala spp. by presenting blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata) with slides of moths in different orientations on trees. They showed that both the moth orientation and tree species combined to influence the birds' prey detection rate, such that orientation affected detectability but only on some tree species. While this pioneering experiment was an important step towards establishing direct evidence that behavioural orientation influences crypsis, there were some limitations, including inevitable low sample size of predators and the fact that only three levels of orientation were explored (up, down and right). Most importantly, although the authors described the high-contrast markings in the Catocala species they investigated (which they referred to as faint or prominent disruptive patterns), the underlying reasons for the orientation effects they observed were not further investigated.

In the present study, we investigated the importance of orientation in reducing detectability and conducted tests to elucidate the underlying mechanisms involved. First, we set out to determine whether two groups of naturally occurring moth species orient non-randomly on tree trunks in the field, and whether there was any between-group variation. We then used a computer-based system of humans ‘foraging’ for images of the moths against images of trees to test whether moth orientation influenced survivorship in our system, and, if so, whether the results were consistent with our field data on the natural orientations of the moth species concerned. Finally, to test whether the moth orientation effect could be explained by the moths' alignment to trees' patterns, we horizontally rotated the same tree images that were presented, and asked whether the optimal orientations of the moth species were concomitantly altered.

2. Material and methods

(a) Field survey of moths' body orientations

Moths were intensively searched for in two mixed deciduous forests near Ottawa, Canada, between 21 June and 8 August 2006. The forests were Stony Swamp Conservation Area (45°,17′,58.29″ N; 75°,49′,11.06″ W) and Monk Woods Environment Park (45°,20′,23.86″ N; 75°,55′,55.84″ W), with common tree species being basswood (Tilia americana), bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis), bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa), ironwood (Ostrya virginiana), red maple (Acer rubrum), red oak (Quercus rubra), sugar maple (Acer saccharum), white ash (Fraxinus americana) and white birch (Betula papyrifera). Our protocol involved taking transects through the field sites and any tree, of girth greater than 10 cm, was assessed for the presence of resting moths. This assessment was a two-stage process. First, from several metres away the tree was visually scanned. Then, the tree was approached and a tactile search was used. This touching of the tree ensured that no moths on that tree had been overlooked. If a moth had been missed, then ‘tapping’ the tree was intended to frighten the moth out of hiding. While in such cases the data on moth orientation were lost, it provided a good fail safe, ensuring that the most cryptic moths on tree trunks were not being missed. Clearly, this method only provides an assessment of moths’ presence on lower sections (the first 3 m) of tree trunks and no attempt was made to search leaf litter or higher branches.

On locating a moth in its natural resting position we recorded the moth species, host tree species and time of day. A photograph of the moth in its natural position was taken using a Canon PowerShot Pro1 from roughly 30 cm away. The camera's lens was then set to its widest zoom to ensure that the edges of the tree were included in the frame. These photographs were later used to extract orientations of moths, relative to that of the tree, using ImageJ. After these in situ recordings were completed, we captured the moth using either a net or a jar and stored it for later confirmation of species identity.

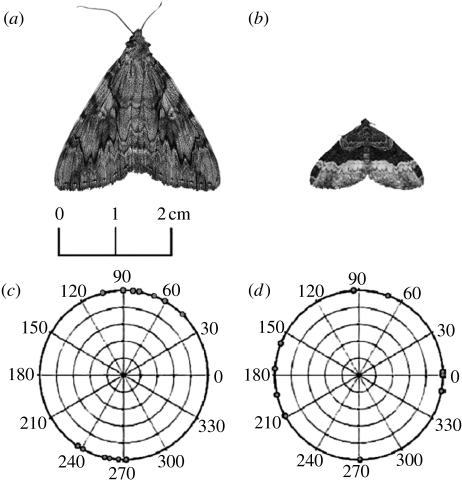

(b) Human predator system: testing the effect of orientation on crypsis

Between July and September 2007, approximately 20 nights were spent light trapping to collect new moth specimens, including those species that were most commonly found in the field from the previous year. This collection effort yielded nine good-condition specimens of Catocala cerogama (more Euphyia intermediata were caught but only nine were used for this experiment, matching the number of C. cerogama specimens used). Specimens were caught at night, collected in pill jars, refrigerated until the morning and killed using an ethanol-laced jar. Once dead, the specimens were mounted together on brown card in a natural resting position (L. Scott 2007, personal communication). C. cerogama has complex contrasting markings, in the form of wavy lines with no clear directionality (figure 1). As well as its concealment coloration, C. cerogama has conspicuous markings on its hind wings, but they are masked by cryptic forewings when at rest. Catocala species are also known for their polymorphism (Bond & Kamil 2002), but the colour pattern differences among the individual moths used in our experiment were relatively subtle. The specimens of E. intermediata all had high-contrast markings, forming a band perpendicular to its body axis (figure 1). In our 2006 field season we observed that both of these species were commonly found on sugar maple (A. saccharum) trees, but they showed no significant preference in choosing this tree species over other trees (Callahan 2007).

Figure 1.

Photographs of the study species (a) C. cerogama and (b) E. intermediata and the angular distributions of individual (c) Catocala spp. and (d) Larentiinae representatives found on trees in the field. Black circles mark the position of the head, relative to the orientation of the tree (90° at vertical). Angular distributions are clearly non-uniform for Catocala spp. yet relatively uniform for Larentiinae representatives.

The nine specimens of each moth species (C. cerogama and E. intermediata), all mounted on brown card, were photographed in the field against each of nine sugar maples. All photographs were taken on overcast days in September 2007. Trees were photographed with and without the moth specimens in quick succession to ensure identical lighting conditions: of these photographs, the ones without the moths were used as background images and ones with, were merely used to excise moths. Moths and trees were photographed using a Canon EOS D60 with an EF 24–70 mm f/2.8 L USM lens mounted on a tripod with a distance of 120 cm between camera's sensor and the tree. The zoom was set to 55 mm (equivalent to the human eyes' diagonal field of view (Ray 2002)). Photographs were recorded in RAW to enable the colour temperature to be selected post-capture. By photographing on dull overcast days, we minimized non-uniform illumination of the tree caused by dappled sunlight; such variation in lighting conditions within the image of the tree are unwanted because they will contribute to an artificial enhancement of the moths' conspicuousness, due to the excised moth no longer matching the illumination of its background.

Each tree background was matched with an image of a unique C. cerogama and E. intermediata specimen, excised from the mounted sample of moths photographed under the same conditions as the tree was photographed. The uniform brown card region around each moth was selected using the Adobe Photoshop magic wand tool, with a low tolerance set to between 5 and 20 RGB colour value deviation, between neighbouring pixels. This selected area was deleted and then the edges around the moth were manually cleaned using the Adobe Photoshop eraser to remove shadows, leaving just the moth. Moth targets were saved as. PNG files with transparent backgrounds. This process was repeated for two unique specimens (one per species) for each of the nine trees. Since C. cerogama is approximately six times the surface area of E. intermediata, we enlarged E. intermediata targets and their respective backgrounds to render this second target species more comparable in size. This resulted in forming a new set of ‘zoomed in’ background images, derived from the original background image set. Irrespective of the species, the dimensions of the background tree were 600 pixels wide ×900 pixels high (and the reverse for horizontally rotated trees) while the moth target images (transparent outside the actual image of the moth) were placed to fill a square area of 75 pixels wide ×75 pixels height.

We developed a Microsoft Visual Basic (Visual Basic 2008) application to present images of moth target superimposed on tree backgrounds and to quantify the elapsed time that human subjects took to detect moths (assuming it was detected at all). For each human subject, a set of 90 tree images were presented on a computer monitor. In doing so, the nine tree backgrounds we had photographed were each presented 10 times: for eight of these presentations the moth target was randomly positioned in the image and set as to one of eight orientations (0, 45, 90, 135, 180, 225, 270 and 315° from vertical), and twice with no moths present. Each image presented to human subjects was a unique pairing of a moth's orientation against its appropriate background—no subject was presented with a given moth in a given orientation more than once, so as to avoid pseudo-replication. The human subjects were presented a maximum of one moth per background (but one-fifth of the time there was no moth target). Moth orientation, as well as presence/absence, was randomized as to the order they appeared. Tree background images were presented in sequence, cycling through all backgrounds before repeating the same backgrounds again: this ensured that the same tree background image was never presented one after the other to invoke change blindness, so that the moth superimposed on the same tree image are not instantly recognizable from short-term visual memory (Rensink et al. 1997). This order was changed between human subjects. Overall, therefore, the same moth image was presented against the same tree image in eight different orientations and we presented a total of nine completely different moth–tree pairs (hereafter referred to simply as tree) in the same way (8 orientations×9 trees=72 moths in total).

One of four foraging environments was presented to each human subject (two species, by two background orientations). For each foraging environment (i.e. C. cerogama on vertical background, C. cerogama on horizontal (flipped) background, E. intermediata on vertical background and E. intermediata on horizontal (flipped) background), we collected data from 24 human subjects (96 different subjects in total), thereby ensuring complete orthogonality in design.

Subjects participated in this human predator system experiment at the Carleton University Maxwell MacOdrum Library. Two computer terminals were set up with the Visual Basic application, viewed using 19″ Stealth Computer Corporation LCD monitors with a screen resolution of 1024×768 pixels. Cardboard screens were erected to minimize disturbance to participants and to reduce the effect of ambient light. Participants were given no indication of the purpose of the experiment, only that it was a foraging exercise and they were only allowed to participate once. The first window presented a trial screen, with a moth in all eight different orientations simultaneously (in random, yet non-overlapping positions) and the subject was asked to find all the moths on the screen—this acted as a short training period for the naive subjects. The trial screen resembled the screen for the real experiment and the researcher orally explained which buttons to press. The time taken to attack moths (in milliseconds) from the first presentation of the moth was recorded automatically.

(c) Statistical analysis

We quantified the in situ resting body orientation of free-ranging moths in the field from photographs using ImageJ. The resting site angular distributions for each species were tested using Rayleigh's test for angular distributions (Zar 1999), with the null hypothesis that moth resting orientations were uniformly distributed.

To examine the effect of moth orientation (eight levels) on moth ‘survivorship’, we fitted general linear models (GLMs) to the data. All statistical tests were carried out using SPSS v. 15. Throughout our analyses, moth orientation was expressed in one of two complementary ways: either absolute (so that the north–south axis, for example, is always upwards–downwards on the monitor) or relative to the trees rotation (such that north–south axis is always along the trunk of the tree: this measure is therefore sensitive to the tree background rotation). To avoid complex interactions in the fitted model, a separate GLM was fitted to the data for each moth species. For the first fit of the GLM, our dependent variable was the proportion of the 24 human subjects (arcsine transformed) that failed to detect a moth when it was presented in a particular orientation on a particular tree, and the tree was presented vertically or horizontally. Moth orientation (absolute or relative) and tree rotation were treated as fixed factors, while tree (representing a subset of possible factor levels) was treated as a random factor. All pairwise interactions were included, but higher order interactions were necessarily omitted. To complement this analysis, we fitted another GLM, with the time taken to detect those moths that were attacked the dependent variable (square root, log transformed to ensure normality and homogeneity of variance). Here, moth orientation was treated as a fixed factor, while tree and human subject were treated as random factors. By including a human subject effect, data from the two tree rotations were necessarily considered separately (since human subjects only participated in one of the four experiments).

3. Results

(a) Field survey of moths' body orientations

Fifteen specimens of Catocala spp. (comprising C. cara, C. cerogama, C. ilia, C. semirelicta, C. subnata and C. unijuga) and 11 specimens of the family Larentiinae (comprising Epirrhoe alternata, E. intermediata, Xanthorhoe labradorensis) were found in natural resting positions. Catocala spp. exhibited a highly significant preference for head-up/head-down orientation (figure 1) between 60 and 105° and 235 and 272° (Z=11.2, n=15, p<0.001). However, we could not reject the null hypothesis that Larentiinae representatives were orientated uniformly (figure 1) on tree trunks (Z=1.2, n=11, p>0.05).

(b) Human predator system: testing the effect of moth orientation on survivorship

On fitting a GLM to the arcsine transformed proportion of moths missed per person for each species, the main effects of tree and tree rotation were significant for both species (table 1). There was no significant effect of absolute moth orientation, but the interaction term of absolute moth orientation×tree rotation was significant for both species (table 1; figure 2). When relative moth orientation was used instead of absolute moth orientation in the same model, the relative moth orientation became significant while the moth orientation×tree rotation effect became non-significant (EA table 1). This suggests that it is the orientation of the moth relative to the tree that is primarily responsible in influencing detectability (not the absolute orientation of the moth).

Table 1.

GLMs of arcsine transformed overall mean proportion missed (survivorship) per human subject for each moth species with three main effects (absolute moth orientation, tree rotation and tree) and all pairwise interactions. Test statistics for the GLM are represnted: FS (d.f.) significance (***=p<0.001, **=p<0.005, *=p<0.05, p>0.05=n.s.). All factors in the GLM are fixed, except for tree which is a random factor.

| GLM factors and interactions | C. cerogama | E. intermediata |

|---|---|---|

| absolute moth orientation | 1.95 (7,56) n.s. | 1.17 (7,56) n.s. |

| tree rotation | 11.66 (1,8)* | 5.64 (1,8)* |

| tree | 26.26 (8,2.69)* | 30.51 (8,6.99)*** |

| absolute moth orientation×tree rotation | 4.50 (7,56)*** | 3.47 (7,56)** |

| absolute moth orientation×tree | 0.70 (56,56) n.s. | 0.66 (56,56) n.s. |

| tree×tree rotation | 0.87 (8,56) n.s. | 5.4.3 (8,56)*** |

Figure 2.

Mean (±1 s.e.) proportion of moth targets missed ((a) C. cerogama and (b) E. intermediata) on (i) vertically and (ii) horizontally rotated trees according to absolute moth orientation. Images of moth species (not to scale) have been thresholded to illustrate their high-contrast marking parallel and perpendicular to body axis.

For the GLM where detection time was set as its response variable, the main effects of tree were significant for both species, but moth orientation was only significant for C. cerogama (table 2; figure 3), indicating that any orientation effect on attack time, if present, was less marked for E. intermediata. Indeed, the significant human subject×moth orientation interaction suggests that orientation had an effect on detection time in E. intermediata, but that this effect was rather subject specific. Nevertheless, changes in the mean detection time of those moths that were eventually attacked roughly paralleled the proportion of moths missed in their different orientations (figures 2 and 3).

Table 2.

GLMs of square root, log-transformed detection time of each moth attacked, for each species and tree rotation with three main effects (absolute moth orientation, human subject and tree) and all pairwise interactions. Test statistics reported for the GLM are: FS (d.f.), significance (***p<0.001, **p<0.005, *p<0.05, p>0.05=n.s.).

| GLM factors and interactions | C. cerogama | E. intermediata | |

|---|---|---|---|

| vertical | absolute moth orientation | 5.10 (7,45.9)*** | 0.98 (7,73.2) n.s. |

| tree | 17.41 (8,65.4)*** | 10.00 (8,105.06)*** | |

| human subject | 4.32 (23,104.5)*** | 3.73 (23,199.5)*** | |

| absolute moth orientation×tree | 1.37 (56,1054)* | 1.12 (56,846) n.s. | |

| absolute moth orientation×human subject | 0.94 (161,1054) n.s. | 1.26 (161,846)* | |

| tree×human subject | 1.25 (183,1054)* | 1.77 (172,42.1)*** | |

| horizontal | absolute moth orientation | 7.02 (7,45.0)*** | 1.99 (7,74.81) n.s.(p=0.068) |

| tree | 20.81 (8,67.6)*** | 28.53 (8,42.16)*** | |

| human subject | 5.01 (23,111.5)*** | 4.03 (23,113.91)*** | |

| absolute moth orientation×tree | 1.45 (56,1124)* | 0.95 (56,954) n.s. | |

| absolute moth orientation×human subject | 1.02 (161,1124) n.s. | 0.95 (161,954) n.s. | |

| tree×human subject | 1.32 (184,1124)** | 0.97 (177,954) n.s. |

Figure 3.

Mean (±1 s.e.) detection time for moth targets ((a) C. cerogama and (b) E. intermediata) on (i) vertically and (ii) horizontally rotated trees according to absolute moth orientation. Images of moth species (not to scale) have been thresholded to illustrate their high-contrast markings. The letters assigned to each error bar are generated from Tukey's post hoc analysis and represent statistically homogeneous subsets at α=0.05 for each orientation.

Tukey's post hoc tests showed significant differences in the mean detection time of C. cerogama in different orientations. Thus, on vertical trees, the south orientated moth specimens had the longest detection times, which were significantly longer than the west, east and northeast orientated moths, which had the shortest detection times. By contrast with the horizontal trees, the south orientated moths had among the shortest detection times, while those orientated east had the longest detection times. Differences in detection time of E. intermediata images in different orientations were less marked. The longest mean detection time on vertical trees was for west orientated moths, but these moths only took significantly longer to detect than southwest orientated moths.

4. Discussion

Since Kettlewell's (1958) classical experiments were on background selection by melanic forms of Biston betularia, there has been much debate regarding the natural resting location of moths on trees (Sargent 1966). We do not discount the possibility that the moth species in this study use tree branches and even leaf litter for concealment. However, even if only a small proportion of moths naturally choose tree trunks to rest on, we suspect it is these moths that have most to gain from appropriate concealment coloration and behavioural alignment. Moreover, our questions were necessarily limited to whether those moths found on tree trunks exhibited a non-uniform resting orientation and whether this choice of resting orientation could be understood on the basis of reduced detectability.

It has long been known that many moth species exhibit non-random resting orientations on both artificial (Sargent 1966, 1968, 1969d) and natural (Endler 1984) substrates. Such orientation behaviour has been assumed to enhance moth crypsis, although the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. In our experiment, we extended previous work done on the resting orientations of nocturnal moths on trees by manipulating the rotation of the background relative to that of the moth. Our primary aim was to test whether the moth orientation effect was a product of some form of interaction between directional aspects of the appearance of the moth and its background.

We found that moth orientation had a significant effect on crypsis and that the optimal orientation depended on the background's rotation. Thus, moth orientation was shown to have a significant effect on survivorship in the combined dataset of vertical and rotated tree images, showing up as an interaction between absolute moth orientation×tree rotation (table 1) and in the main effect of relative moth orientation (see supplementary table 1 in the electronic supplementary material). Collectively, these results indicate that the maximally cryptic moth orientations are influenced in some important way by the rotation of the tree. For example, south orientated C. cerogama had the highest survivorship on vertical trees but the lowest survivorship on horizontal trees. Likewise, west and east orientated E. intermediata had the highest survivorship on vertical trees but the lowest survivorship on horizontal trees (figure 2). One might argue that the effects of tree rotation on the proportion of moths missed (and the mean detection time of moths attacked) arose because we used a different group of humans for vertical and horizontally rotated trees. However, we feel it highly unlikely that the roughly perpendicular switch in optimal orientations arose for any other reason than the perpendicular switch in tree rotation.

A key feature of sugar maple bark is its prominent furrows, creating high-contrast patterning running up and down the tree. By presenting the tree images vertically (natural) and horizontally (artificially rotated), the directionality of the trees' prominent patterns was altered. Given the corresponding changes in optimal orientation of moths with tree rotation, it seems likely that the different markings on the moths (and/or their shape) somehow match those of the bark. Our interpretation is further supported when we note that the two moth species investigated have contrasting patterns and shapes (with E. intermediata exhibiting clear markings perpendicular to the axis of its body and C. cerogama exhibiting a more complex pattern) and also exhibit different optimal orientations. That said, certain aspects of our data are not readily understood. For example, south orientated C. cerogama on vertical trees appear to have higher survivorship than north orientated moths under the same conditions. This outcome seemingly arises as a product of some subtle interaction between moth body pattern (or even moth shape) and tree orientation, although it is difficult to identify the source of this interaction. Pietrewicz & Kamil (1977) likewise found differences in the detectability of south and north orientated Catocala, the precise result varying with Catocala species.

It is possible that selective forces other than crypsis act on moth orientation in the field; for instance, orientating down for ease of escape from predators. However, re-assuringly our field data on C. cerogama's non-uniform resting orientation correspond to the orientations that have been shown to maximize survivorship in our human predator system. For this case at least, it would seem selective pressures to enhance crypsis have influenced C. cerogama's resting orientation. For the Larentiinae representatives, the null hypothesis that natural resting orientation is uniform could not be rejected. This result could be a false negative (indeed 75% of all records of this moth were within ±30° of the horizontal, whereas only 25% of records were within ±30° of the vertical). However, we note that moth field resting orientation was necessarily combined between tree species and it is possible that Larentiinae representatives orient in different fashions on different tree species. Likewise, while Larentiinae representatives have highly similar colour patterning, E. alternata, E. intermediata and X. labradorensis could conceivably show heterogeneous orientation behaviour. A final, unlikely, alternative hypothesis is that Larentiinae representatives' high-contrast markings allow their (potentially) disruptive camouflage to function independent of orientation.

Different tree–moth combinations seem to differentially affect the degree to which moth orientation influences survivorship. The effect of tree specimen on moth survivorship under different orientations is apparent in supplementary figure 1a,b in the electronic supplementary material, which indicates that survivorship differences due to orientation were most evident on backgrounds where the moth had a high mean probability of being missed. Pietrewicz & Kamil (1977) similarly showed that orientation had an effect on survivorship, but only when the moths were presented against those tree species where they were hard to detect. Here, we have shown that a similar phenomenon can arise within a single tree species that exhibits intraspecific variation in appearance. These results link well to the findings of Merilaita (2003) who argued that ‘the difficulty of a detection task is related to the visual complexity of the habitat’, so that prey might find it easier to evolve ways of reduced detection in more visually complex backgrounds. Animals other than moths may also enhance their background matching through appropriate choice of resting orientation. However, our experiments suggest that selection will only act on such behaviour when (i) the detection task is generally difficult and (ii) the background has some form of directional based pattern, generating an advantage from alignment.

One of the potential disadvantages of using a human predator system is that it ignores potential colour pattern information that is beyond human sensory perception (notably, UV reflection; Cuthill et al. 2000). Although tree trunks generally have a low UV content, avian predators may still perceive the hue of these backgrounds differently compared with trichromatic humans (Hart & Hunt 2007). While the use of human predator systems has been shown to produce results that roughly correspond to field survivorship measures (e.g. Fraser et al. 2007; Cuthill & Székely 2009), one should be careful not to over-extrapolate results from human predators to natural predators.

5. Conclusion

Moth resting orientation on trees in the field varies, and can be non-random depending on moth species. Although orientation had been suggested to enhance moths' camouflage, we are not aware of any experiments that have tested precisely why moths experience the reduced detection rates from particular orientations. Here, we combined field data on moths' in situ orientation with an investigation of the benefits of orientation in two moth species, using a human predator system. Not only did the moths' orientation have an effect on survivorship, this effect could be linked directly to how the background tree image was presented (vertical or horizontally flipped) and how the moths themselves were patterned. Collectively, these data provide support for moths' natural orientation behaviour being an adaptive response to fit directional elements of their backgrounds, so as to enhance their crypsis.

Acknowledgements

Use of human subjects was approved by the Carleton University Research Ethics Committee and conducted according to the guidelines set out in Canada's Tri-Council policy statement on ethical conduct for research involving humans.

This research was supported by Discovery grants from the Natural Science and Engineering Council of Canada (NERC) to J.-G.J.G. and T.N.S. and an NSERC summer studentship to A.C. and T.N.S. Permission to sample moths was provided by the National Capital Commission. We sincerely thank Lynn Scott for confirming the identity of species collected from the field and many useful discussions. Finally, we are very grateful to Carleton University's Maxwell MacOdrum Library staff for their hospitality in hosting our human predator experiments and to the students who participated in these experiments.

Footnotes

One contribution of 15 to a Theme Issue ‘Animal camouflage: current issues and new perspectives’.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary table 1: GLMs of arcsin transformed mean proportion missed (survivorship) for each moth species, with three main effects (Relative moth orientation, Tree rotation (both fixed effects) and Tree (random effects)) and all pairwise interactions. Test statistics reported for the GLM are: FS [dfs], sig. (***=p<0.001, **=p<0.005, *=p<0.05, p>0.05=NS). Supplementary Figure 1 a and b: The mean (+/−1 standard error) moth targets missed per tree, for each tree image and relative orientation of C. cerogama and E. intermediata (data on horizontal and vertical tree rotations combined). Differences in survivorship between moths with different orientations are more evident in those trees in which moths are relatively hard to detect. Supplementary Figure 2 a, b, c and d: Colour images of C. cerogama (a and b) and E. intermediata (c and d) presented in their South (a and c) and West (b and d) relative orientations. These target moths are ringed in red.

References

- Bond A.B., Kamil A.C. Visual predators select for crypticity and polymorphism in virtual prey. Nature. 2002;415:609–613. doi: 10.1038/415609a. doi:10.1038/415609a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond A.B., Kamil A.C. Spatial heterogeneity, predator cognition, and the evolution of color polymorphism in virtual prey. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:3214–3219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509963103. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509963103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, A. 2007 Quantifying crypsis: analyzing the resting site selection of moths in their natural habitats. Unpublished BSc thesis, Department of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa.

- Cott H.B. Adaptive coloration in animals. Methuen & Co. Ltd; London, UK: 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthill I.C., Székely A. Coincident disruptive coloration. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2009;364:489–496. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0266. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthill I.C., Partridge J.C., Bennett A.T.D., Church S.C., Hart N.S., Hunt S. Ultraviolet vision in birds. Adv. Study Behav. 2000;29:159–214. doi:10.1016/S0065-3454(08)60105-9 [Google Scholar]

- Cuthill I.C., Stevens M., Sheppard J., Maddocks T., Parraga C.A., Troscianko T.S. Disruptive coloration and background pattern matching. Nature. 2005;434:72–74. doi: 10.1038/nature03312. doi:10.1038/nature03312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler J.A. Progressive background in moths, and a quantitative measure of crypsis. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1984;22:187–231. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1984.tb01677.x [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S., Callahan A., Klassen D., Sherratt T.N. Empirical tests of the role of disruptive coloration in reducing detectability. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2007;274:1325–1331. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0153. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart N.S., Hunt D.M. Avian visual pigments: characteristics, spectral tuning, and evolution. Am. Nat. 2007;169:S7–S26. doi: 10.1086/510141. doi:10.1086/510141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelman E.J., Baddeley R.J., Shohet A.J., Osorio D. Perception of visual texture and the expression of disruptive camouflage by the cuttlefish, Sepia officinalis. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2007;274:1369–1375. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0240. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettlewell H.B.D. A survey of the frequencies of Biston betularia L. (lep.) and its melanic forms in Britain. Heredity. 1958;12:51–72. doi:10.1038/hdy.1958.4 [Google Scholar]

- Kingsland S. Abbott Thayer and the protective coloration debate. J. History Biol. 1978;11:223–244. doi:10.1007/BF00389300 [Google Scholar]

- Merilaita S. Crypsis through disruptive coloration in an isopod. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1998;265:1059–1064. doi:10.1098/rspb.1998.0399 [Google Scholar]

- Merilaita S. Visual background complexity facilitates the evolution of camouflage. Evolution. 2003;57:1248–1254. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00333.x. doi:10.1554/03-011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merilaita S., Lind J. Background-matching and disruptive coloration, and the evolution of cryptic coloration. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2005;272:665–670. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.3000. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss R., Jackson R.R., Pollard S.D. Hiding in the grass: background matching conceals moths (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) from detection by spider eyes (Araneae: Salticidae) NZ J. Zool. 2006;33:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrewicz A.T., Kamil A.C. Visual detection of cryptic prey by blue jays (Cyanocitta cristata) Science. 1977;195:580–582. doi: 10.1126/science.195.4278.580. doi:10.1126/science.195.4278.580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S. Focal Press; Cambridge, MA: 2002. Applied photographic optics: lenses and optical systems for photography. [Google Scholar]

- Rensink R.A., Oregan J.K., Clark J.J. To see or not to see: the need for attention to perceive changes in scenes. Psychol. Sci. 1997;8:368–373. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00427.x [Google Scholar]

- Ruxton G.D., Sherratt T.N., Speed M. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2004. Avoiding attack: the evolutionary ecology of crypsis, warning signals and mimicry. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent T.D. Background selection of geometrid and noctuid moths. Science. 1966;154:1674–1675. doi:10.1126/science.154.3757.1674 [Google Scholar]

- Sargent T.D. Cryptic moths—effects on background selections of painting circumocular scales. Science. 1968;159:100–101. doi: 10.1126/science.159.3810.100. doi:10.1126/science.159.3810.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent T.D. Background selections of pale and melanic forms of cryptic moth Phigalia titea (Cramer) Nature. 1969;222:585–586. doi:10.1038/222585b0 [Google Scholar]

- Sargent T.D. Behavioral adaptations of cryptic moths. 2. Experimental studies on bark-like species. J. NY Entomol. Soc. 1969;77:75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent T.D. Behavioral adaptations of cryptic moths. V. Preliminary studies on an anthophilous species, Schinia florida (Noctuidae) J. NY Entomol. Soc. 1969;77:123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Sargent T.D. Behavioural adaptations of cryptic moths 3. Resting attitudes of 2 bark-like species, Melanolophia canadaria and Catocala ultronia. Anim. Behav. 1969;17:670–672. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(69)80010-2 [Google Scholar]

- Sargent T.D., Keiper R.R. Behavioural adaptation of cryptic moths. I. Preliminary studies on bark-like species. J. Lepid. Soc. 1969;23:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer H.M., Stobbe N. Disruptive coloration provides camouflage independent of background matching. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2006;273:2427–2432. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3615. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M. Predator perception and the interrelation between different forms of protective coloration. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2007;274:1457–1464. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0220. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M., Merilaita S. Defining disruptive coloration and distinguishing its functions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2009;364:481–488. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0216. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M., Cuthill I.C., Párraga C.A., Troscianko T. The effectiveness of disruptive coloration as a concealment strategy. In: Alonso J.-M., Macknik S., Martinez L., Tse P., Martinez-Conde S., editors. Progress in brain research. vol. 155. Elsevier; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M., Cuthill I.C., Windsor A.M.M., Walker H.J. Disruptive contrast in animal camouflage. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2006;273:2433–2438. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3614. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer G.H. Concealment coloration in the animal kingdom: an exposition of the laws of disguise through color and pattern. Macmillan; New York, NY: 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R.J., Bartlett L.A., Marples N.M., Kelly D.J., Cuthill I.C. Prey selection by wild birds can allow novel and conspicuous colour morphs to spread in prey populations. Oikos. 2004;106:285–294. doi:10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.13089.x [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson D.M., Sherratt T.N. The art of concealment. The Biologist. 2008;55:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zar J.H. 4th ed. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1999. Biostatistical analysis. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary table 1: GLMs of arcsin transformed mean proportion missed (survivorship) for each moth species, with three main effects (Relative moth orientation, Tree rotation (both fixed effects) and Tree (random effects)) and all pairwise interactions. Test statistics reported for the GLM are: FS [dfs], sig. (***=p<0.001, **=p<0.005, *=p<0.05, p>0.05=NS). Supplementary Figure 1 a and b: The mean (+/−1 standard error) moth targets missed per tree, for each tree image and relative orientation of C. cerogama and E. intermediata (data on horizontal and vertical tree rotations combined). Differences in survivorship between moths with different orientations are more evident in those trees in which moths are relatively hard to detect. Supplementary Figure 2 a, b, c and d: Colour images of C. cerogama (a and b) and E. intermediata (c and d) presented in their South (a and c) and West (b and d) relative orientations. These target moths are ringed in red.