Abstract

This paper presents data from a study that collected observational data, survey data, and breath samples to estimate blood alcohol concentrations (BrAC) from patrons attending 30 bars. The study examines: 1) drinking behavior and settings prior to going to a bar; 2) characteristics of the bar where respondents are drinking; 3) person and environmental predictors of BrAC change (entrance to exit). Purposive sampling of bars that cater to young adults gave a sample of 30 bars. Patrons were randomly selected from bars (n=839). Approximately half of the sample was female (48.7%). Nearly three-quarters of participants reported drinking before attending the bar. Serving practices of the bars were observed; majority of bars served excessive amounts of alcohol in short periods of time. On average, those who drank before attending the bar had BrACs at approximately half the legal limit. Implications for responsible beverage service coupled with law enforcement strategies are discussed.

Keywords: Environment, Bars, BrAC, Drinking settings

1. Introduction

Alcohol consumption in bars and taverns is common and heavy drinking often occurs in these settings. Okraku estimated that 30% of all Americans visit a bar once a month (Okraku, 1998). The Brewers Association of Canada estimated that 24% of all alcohol consumed in the U.S. was consumed in bars or taverns (Edwards et al., 1994). In a series of national studies, Wechsler and associates reported that 53% of underage students and 86% of legal drinking aged students (≥21 years) attended a bar in the past month, with over a third in each age group reporting five or more drinks during their most recent bar visit (Wechsler et al., 2000a). Similarly, Clapp et al. (Clapp et al., 2000) reported that college students drank an average of 8.4 (SD=2.4) drinks per visit to a bar. Finally, in a study of New Zealand college students, bars and other public drinking venues were the wettest settings, with over 60% of respondents having estimated blood alcohol concentrations over .08 (grams per deciliter) (Kypri et al., 2007).

One might argue the systematic study of drinking behaviors began with Sherri Cavan’s seminal qualitative study, Liquor License, in which she provided a rich description of the social and physical environments of bars in San Francisco (U.S.) as they relate to alcohol consumption (Cavan, 1966). In the decades that followed, researchers began to examine bars as a drinking context (Clark, 1982; Gusfield, 1982; Harford and Gaines, 1979), as well as a place to intervene in alcohol-related problems such as intoxication (Howard-Pitney et al., 1991; Saltz, 1997), drunk driving (McKnight and Voas, 1991), and aggression (Graham et al., 2004). Many of these studies found that bar environments were amenable to structural interventions, and such interventions can be effective (Holder et al., 1997).

The extant literature related to alcohol consumption in bars is limited in two ways. First, little conceptual work has guided such work (Gruenewald, 2007). Thus, our understanding of the social-ecological mechanisms which operate among bar patrons and bar environments, both physical and social, is limited. Second, very few studies (Saltz, 1997; Thombs et al., 2008b) have employed methodologies which simultaneously examine environmental and individual characteristics, and no study to date has combined individual-level data collections (including biological measures of BAC) and observational data of the bar environment.

The present study fills some of the gaps in the literature noted by addressing the following research aims: 1) using the extant literature to conceptualize person and environmental level variables; and 2) examining person-level and environment-level data simultaneously collected. Overall, we are interested in addressing the following research question: 1) What are the relationships among individual characteristics, environmental factors, and BrAC among young adults patronizing bars?

1.1. Conceptualizing Person and Environmental Predictors of Drinking

Alcohol outlets can be conceptualized as a place where “drinkers exchange economic and social goods …and incidentally form social groups for drinking that can promote a number of different problem behaviors” ((Gruenewald, 2007), p.102). Thus, alcohol outlets inherently represent a place where the interaction between individuals and their environment is central to drinking outcomes (Harford, 1979). At the community level, Gruenwald (2007) suggested that market demands result in variation among alcohol outlets in the types of drinkers they attract. Similarly, individuals seek out environments that are in sync with their expectancies, motivations, and goals (Gaines, 1982; Gruenewald, 2007).

Conceptually, such interactions between individuals and the social environment generate both protective and risk attributes within contexts. These formed protective and risk attributes vary in duration and magnitude within a situation and represent the nexus of individual and environment factors related to behavior. Therefore, they represent “leverage points” that remain critical to prevention and health promotion (Stokols, 2000b). As Stokols noted:

Most situations are characterized by a mixture of positive and negative environmental circumstance and health outcomes. Thus, an important challenge for future research is to assess the overall health promotive capacity of environments on the basis of cumulative analysis and weighting of their positive and negative features as they affect occupants’ well-being ((Stokols, 2000a) p.140).

1.2. The Study of Drinking in Bars

Of particular interest within such a social system are the specific individual and environmental attributes that contribute, either independently or in interactive ways, to alcohol consumption. At the individual-level, Greenfield and Room reported data from three national household surveys (U.S.); they found that 30% of respondents in 1990 felt it was it was appropriate for men to drink enough in bars to “feel the effects of alcohol (or more)” ((Greenfield and Room, 1997) p.39).

At the bar level, several studies have examined alcohol serving practices as a correlate of heavy drinking. Stockwell, Lang, and Rydon used national survey data from Australia to examine alcohol related harms (Stockwell et al., 1993). A recent study by Thombs et al. illustrated that low-price drink specials were associated with BACs above .08 (Thombs et al., 2008a). They found that drinking in bars resulted in the greatest proportion of alcohol-related harm, and over-service to already intoxicated patrons was the strongest predictor of alcohol-related problems. At the socio-environmental level, Van de Goor found that drinking in larger groups or in places with loud music tended to be associated with heavier drinking, while being engaged in dancing was associated with less drinking (Van de Goor et al., 1990). Similarly, Gueguen et al., reported that patrons who were in an environment with louder sound levels were likely to consume more alcohol than those in quiet environments (Gueguen et al., 2004). In addition to group size, being around many intoxicated people was found to increase risk for heavy drinking in a bar setting (Clapp et al., 2006). In contrast, a household survey of Australian adults found that both dancing and a high proportion of drunk patrons predicted high risk drinking (Lang et al., 1995). Similar to Clapp et al., Lang and associates found a positive relationship between drunken patrons and individual heavy drinking (Lang et al., 1995). Finally, in a bar lab study, Bot and colleagues reported lighter drinkers participating in in-bar activities, such as billiards, had a slower rate of alcohol consumption, but heavy drinkers tended to drink even more when not participating in such activities to compensate for periods of reduced drinking during these activities (Bot et al., 2007).

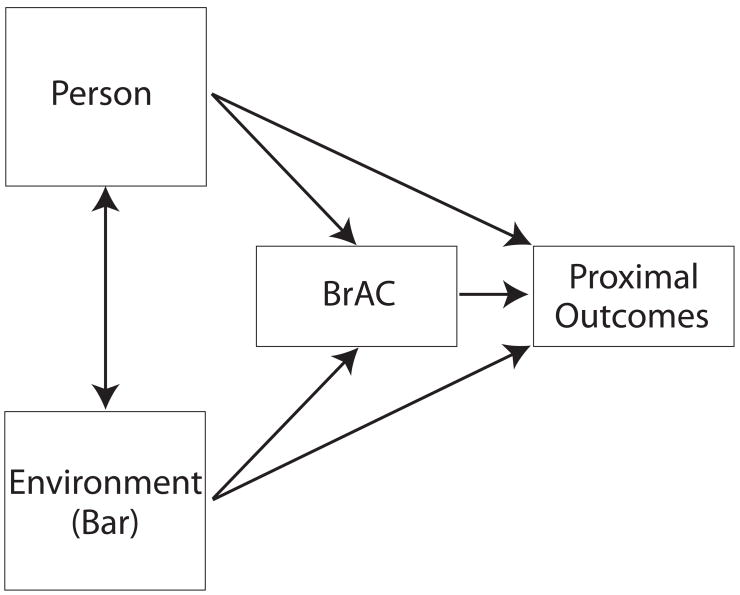

Based on this literature and concepts rooted in ecological approaches to alcohol (Gruenewald, 2007) and health behavior (Hovell et al., 2002), we propose the following conceptual model to guide the proposed study (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Ecological Model of Alcohol Use and Problems

Within this model, person-level variables directly relate to environment in a reciprocal fashion. Both person and environment influence BrAC (Breath Alcohol Concentration), and proximal drinking outcomes. In turn, person-level variables interact with party environments to influence BrAC and proximal outcomes. Within the conceptual model presented above, BrAC is the immediate outcome of interest. Theoretically as BrAC increases, so does the likelihood of problematic outcomes. Within the ecological framework, specific environmental factors may moderate the likelihood of problem outcomes. Although the current literature concerning alcohol environments and drinking contexts provides insight into the variables important to the above conceptual model, it is important to note that this literature is relatively scant and the specification of variables and relationships should be viewed as exploratory. For the purposes of the present study, we are only examining the first pathway in the model—the influence of person and bar variables as they relate to drinking.

At the individual level, the following variables are of interest: demographic characteristics (gender, ethnicity, student status), pre-bar drinking, drinking history, and intentions/plans for drinking on the night of the drinking event. Numerous studies have found that white males attending college or universities are the heaviest drinkers (Wechsler, 1996; Wechsler et al., 2000b; Wechsler et al., 2002). Thus including race/ethnicity, student status and gender are important to model specification. Similarly, we found drinking history (frequency or heavy episodic drinking) to be a predictor of drinking at specific events in prior studies (Clapp et al., 2003; Clapp et al., 2008; Clapp et al., 2006).

Researchers have proposed that people drink to attain specific outcomes, and drinking behavior serves different functions and needs across social contexts (Cooper, 1994), (Kuntsche et al., 2005). Unlike expectancies (beliefs about the effects of drinking), drinking motives are considered a proximal and necessary aspect for drinking which culminates in the decision about whether or not to drink (Cox and Klinger, 1988). Research has supported this notion of motives as a “final common pathway”, and drinking motives have even been shown to fully mediate the effects of alcohol expectancies on alcohol use (Kuntsche et al., 2007). Even though there are strong associations between drinking motives, expectancies, personality traits, and alcohol use in college students (Westmaas et al., 2007), the close proximity of motives to drinking behaviors makes it an ideal target for further exploration in this population. Thus, we have included variables related to individual’s drinking intentions for the night they reported drinking alcohol.

At the bar level, the availability of food, alcohol (price and access) and dancing/loud music are important to model specification. In a previous study, we found the presence of food was protective of heavy drinking (Clapp et al., 2000). Studies have reported an inverse relationship between the price of alcohol and alcohol consumption (Coate and Grossman, 1988; Gruenewald and Millar, 1993), whereas temporary bars conceptually represent increased availability of alcohol within the bar. Recent studies have also demonstrated loud music to be predictive of heavy drinking (Gueguen et al., 2004; Gueguen et al., 2008).

2. Methods

2.1 Design

We conducted a cross-sectional multi-level study of 30 young adult-oriented bars in a large urban area of southern California. Patrons attending bars were sampled before and after bar attendance.

2.1.1. Bar Sample

Thirty-two bar owners were offered a $500 incentive to allow us access to their establishment and survey their patrons. Overall, we approached 32 bar owners, who all agreed to participate (no refusals). We purposively selected bars that catered to young adults. Bars varied in size and type and included a variety of clubs, neighborhood taverns, and bar/restaurants. Two bars were excluded from analyses because too few patrons participated in our survey (under 10 patrons). Thus, we report data on 30 bars in this study.

2.1.2. Patron Sample

Patron interviews began at 9:00 p.m. and typically concluded at 2:00 a.m. (closing time for bars in California). Surveys were conducted on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights. Two types of surveys were conducted: 1) an Entrance/Exit Survey in which the participants completed a brief survey and breath test before they entered the bar and again when they exited the bar, and 2) an Exit Only Survey designed to examine potential reactivity to the entrance BrAC measure in which the participants completed the brief survey and breath test only upon exiting the bar.

We took BrAC samples using a handheld BrAC test unit (CMI Intoxlyzer SD-400). These units were calibrated by trained research staff each month. Participants blew into the disposable mouthpiece on the handheld test units until a sufficient sample was achieved. After the sample was collected, research assistants recorded the unit number and sample number on the survey form, to be matched after the data were downloaded at the research offices. The collection of BrAC was conducted in a double blind fashion; thus, neither the research assistants nor the respondents had access to a respondent’s BrAC in the field. Respondents were given their sample number with our contact information if they wanted to learn of their BrAC values the following day. All respondents, regardless of condition, received a $10 gift card as an incentive.

2.1.2.1. Pre-Post Group

We randomly sampled patrons in groups, or occasionally as individuals (in cases where a randomly selected patron was alone), using a systematic sampling procedure (i.e. every 2nd case after the initial random group) with a random start. In the case of refusals, we approached the next group entering the bar. Approximately 44.6% (n = 402 groups) of all groups approached refused to participate. Of those participating in the Entrance/Exit survey, 18.7% did not complete the Exit survey. Overall, we interviewed 1040 bar patrons. For analytical purposes we excluded cases with missing values BrAC values, leaving us with 839 cases at the individual level. Overall, based on door counts, we sampled an average of 8.5% of bar patrons attending the bar on the night we conducted the survey (SD=6.0%).

Once a group or individual agreed to participate, we briefly explained the study and obtained verbal consent for participation (this project was approved through the San Diego State University IRB). Next, we conducted a brief field interview that assessed: 1) demographics, 2) drinking intentions for the night and 3) drinking behavior earlier in the day. Demographic items included gender, race/ethnicity, age, weight, student status, Greek-letter organization membership, and membership on an athletic team. Drinking intentions for the night included whether the participant planned to drink, the amount of money the participant planned to spend on alcohol, and a measure of how intoxicated the participant planned to get. If the participant had been drinking they were asked to indicate how intoxicated they felt and when they had their most recent drink. Each respondent was given a hospital style bracelet with unique identifying numbers and was asked for a BrAC sample. Respondents were requested to check back in with the survey staff upon leaving the bar to finish the interview and receive their incentive. An interviewer was responsible for identifying exiting respondents by the bracelet.

When respondents exited the bar, a second field interview was conducted and assessed: 1) transportation to and from the bar, 2) who they were drinking with in the bar, 3) the amount of money they spent in the bar, 4) the number of drinks consumed, 5) the type of drinks consumed, 6) whether they had any negative experiences at the bar, and 7) whether they could obtain illicit drugs if they so desired. A second BrAC sample was collected at this time. The interview items used in this study were all adapted from prior measures (Clapp et al., 2003; Clapp et al., 2006).

2.1.2.2 Post-only Group

On the same night as the pre-test/post-test group interviews, we conducted post-test only interviews. As noted above, these interviews served as a means to examine potential testing effects associated with the entrance interview. Once the first Entrance/Exit participant had exited the bar, we began the Exit Only surveys. We used a combined version of the Exit/Entrance Survey for this survey. For these surveys, we randomly selected an interval (1–5); every ten minutes we approach the randomly selected kth individual. The protocol stipulated this procedure would continue until 15 patrons were surveyed each night; on average, 12 patrons per bar were sampled for this Exit Only survey. A BrAC sample was collected from each respondent. Three hundred and twenty patrons of the 700 approached participated (45.7 % refused to participate) in the Exit Only survey. We found no significant BrAC differences between the Exit Only patrons and the Entrance/Exit patrons. The Exit Only surveys are not included in any of the subsequent analyses.

2.1.3. Bar Observations

On the night of the survey, research assistants posing as patrons assessed the serving and security practices at the bar being surveyed. Our pseudo-patrons (n=2) followed a protocol designed to assess serving practices, rate of service, and drink pricing. The pseudo-patrons entered the bar together between 8:30 pm and 9:30 pm. When entering the bar, they independently observed whether their ID was checked at the door, if there was a cover charge, and the overall environment of the bar (i.e., if bar was crowded, if there was loud music, if people were dancing, and if there were temporary bars).

For bars with servers, the pseudo-patrons secured a single table, noting the time they were seated and the time a server arrived. Intervals between all server visits to the table were timed to determine rate of service. Pseudo-patrons observed servers on the following practices: 1) whether the server asked to see their ID, 2) offered any non-alcoholic drinks, 3) offered drink specials, and 4) offered a menu for food. If the server did not offer drink specials or a menu, the pseudo-patrons requested to see a menu and inquired what the drink specials were for the night.

The pseudo-patrons followed a specific protocol for ordering drinks designed to assess: 1) the rate of service (i.e., time between drinks), and 2) whether servers allow, prohibit, or discourage ordering multiple drinks, including high-alcohol content Long Island Iced Teas (long Island Ice Teas typically contain the equivalent of three standard shots of 80 proof alcohol) in a short time interval. First, they ordered a bottled beer each and an appetizer (if available). When the server left the table, the pseudo-patrons each took turns going to the restroom to discard their beers (all drinks were secretly discarded). On the way back to the table, each pseudo-patron independently stopped at the bar, ordered a glass of water from the bartender, and observed if the bartender was over-pouring or free pouring shots and mixed drinks. When the server returned, the pseudo-patrons each ordered a shot of vodka. Finally, each pseudo-patron ordered two Long Island Ice Teas (a total of four). They each observed whether the server allowed them to order, tried to dissuade, or prohibited them from ordering these multiple high-alcohol content drinks. Pseudo-patrons had their BrACs checked by the research staff immediately after they exited the bar to ensure they did not consume any alcohol during the bar observation.

Thirteen bars in our study had no servers or wait staff. In such cases, we followed a protocol that approximates the above protocol and measured the same constructs (i.e., rate of service, pricing, and responsible beverage service); see Clapp et al. 2007 for a detailed overview of this protocol.

The kappas for agreement between the two pseudo-patrons was high at 0.80 to 1.00 for twelve of the sixteen items measured and reported on (see Clapp et al., 2007 for a more detailed description of the methods used in this study); only those items are used in our analyses (Clapp et al., 2007). For analytical purposes, we created a drink price index that included the price of one Long Island Ice Tea, one beer, and one shot of vodka (M=$15.98, SD=$5.3).

2.2. Analysis Approach

The thirty bars surveyed conceptually represent a series of clustered units. Similarly, our sampling approach of selecting groups also represented a potential level of nestedness. Clustered observations do not ensure independent observations and may result in some level of dependence of observations within each cluster, thus violating the assumption of independence of observations needed to conduct ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. As such, we assessed the intra-class correlation of both bars and groups of respondents to examine any between-cluster variation with regard to post-BrAC based on a three-level (level 1 = bar patron, level 2 = selected group, and level 3 = bar) hierarchical linear model using the MIXED MODELS procedure in SPSS (version 16.0) to determine if hierarchical linear modeling techniques were necessary for our analyses. Results of this analysis revealed an intra-class correlation of 0.20 for the group cluster and 0.02 for the bar cluster; both random effects (group and bar) were significant (p<0.05, one-tailed). Although the intra-class correlation for the bar cluster was negligible (i.e., less than 5% of the variability in post-BrAC is associated with differences between bars), the large intra-class correlation coefficient for groups supports the use of hierarchical linear modeling for our analysis.

For this paper, we focused on two primary hierarchical linear modeling analyses. The first explored the relationship between individual characteristics (level-1), bar characteristics (level-3), and alcohol intoxication (post-BrAC) for the entire evening of drinking. We were interested in examining the association between the following nine level-1 predictors of post-BrAC: patron gender (0 = male and 1 = female) and race (0 = white and 1 = non-white), student status (1 = student, 2 = military, 3 = non-student), pre-partying (started drinking before arriving to the bar; 0 = no and 1 = yes), drinking intentions (0 = did not intend to drink tonight, 5 = intend to get very drunk), played drinking games (0 = no and 1 = yes), plan to continue drinking tonight (0 = no and 1 = yes), number of heavy drinking episodes (5+ drinks) in the past 2 weeks, and total time spent drinking. The following bar level (level-3) variables were also included in this analysis: food availability (0 = no and 1 = yes), temporary bars (0 = no and 1 = yes), people dancing (0 = no and 1 = yes), and an aggregated price of a beer, a shot of vodka, and long island iced tea.

For the second model, we were interested in examining both individual (level-1) and environmental (level-3) factors which influence drinking behavior within a specific drinking environment. Thus, unlike the first analysis which examined individual and bar influences level of intoxication for the entire night, this analysis attempts to isolate changes in intoxication occurring at the bars where participants were recruited for the study. Specifically, this analysis explores individual and environmental predictors associated with changes in BrAC. Because we collected BrAC samples upon entry and exit of the bars surveyed, we calculated the change in a patron’s BrAC as a way of isolating intoxication due to a single drinking environment. The same level-1 predictors and level-3 predictors used in the analysis described earlier were used for this analysis with one exception: Instead of including a variable measuring the total time a participant had been drinking, we calculated the duration of time the participant spent in the bar and included this variable in the model.

2.3. Hierarchical Model Building Strategy

We followed an exploratory hierarchical linear model building strategy suggested by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007). The first step in this model-building process was to eliminate non-significant predictors using bivariate regression. Second, an intercepts-only model (null model) was run so that we could examine the intra-class correlation of the group (level-2) and bar (level-3) clusters. The intercepts-only model excluded all model covariates and was used to examine the intra-class correlation of the group (level-2) and bar (level-3) clusters. For the third step, we analyzed a model with all level-1 predictors which were significant from our bivariate analyses. The fourth step assessed a model (full model) which included both level-1 and level-3 predictors (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). Level-2 (group) variables included the created variables group size, group composition, (proportion males) and group age (mean age per group). We ran a preliminary analysis that included these variables in the model but none were significant. Thus, the variable group (i.e., patrons nested within groups recruited for the study) was only included in the model as a random effect to account for this nesting effect. For the full model, all level-1 covariates were considered fixed as models considering random effects for these predictors (i.e., individual differences between the slopes of these predictors and intoxication) failed to converge. Comparisons of the -2 Likelihood of each model were used to determine whether the addition of predictors with each successive model (i.e., null model to level-1 model) significantly improved model fit.

3. Results

3.1. Bar Characteristics

Of the 30 bars in our sample, most were loud (73.3%), had at least one bartender (56.7%), and offered food (66.7%). Slightly more than one-third (34%) of bars had temporary bars. The average price of a beer, a shot of vodka and a long island iced tea was nearly $16 (SD = $5.32). Drink specials were offered by only 10% of the servers. At over a third of the bars, bartenders over-poured drinks. Of particular interest, over 90% of the servers sold our pseudo-patrons a beer, a shot of vodka, and two Long Island Ice Teas each in less than an hour (M=49.6 minutes, SD=16.1).

3.2. Patron Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. Approximately 51% of the participants were male and nearly two-thirds were white (73%). On average, respondents were aged 24.7 years (SD =3.33). Nearly half of the respondents were non-students and ~5% were in the military. More than two-thirds of those interviewed reported heavy episodic drinking (HED), defined as consuming 5 or more drinks on an occasion within the past 2 weeks. Approximately 42% reported 1–3 episodes of heavy drinking, while 24% had 4 or more such occasions in the past two weeks. Most participants had not played drinking games during the evening (5%); however, more than two-thirds (71.5%) reported pre-parting and another 40% reported that they intended to continue drinking after they left the bar. Nearly all participants intended to drink (96.5%) and almost one-in-five (17.2%) reported the intention to get “very drunk.” On average, participants reporting drinking for 260 minutes (4.3 hours), SD = 57.33.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics and Drinking Characteristics

| Variable | Sample (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 838 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 424 | 51.20% |

| Female | 404 | 48.80% |

| Race | ||

| white | 607 | 73.00% |

| non-white | 225 | 27.00% |

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 838 | 24.67 (3.33) |

| Student Status | ||

| Student | 378 | 45.30% |

| Military | 47 | 5.60% |

| Non-student | 410 | 49.10% |

| Heavy Drinking Episodes (past 2 weeks) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 823 | 2.40 (3.10) |

| Pre-Party | ||

| Yes | 597 | 71.50% |

| No | 238 | 28.50% |

| Continue Drinking | ||

| Yes | 317 | 60.10% |

| No | 478 | 39.90% |

| Drinking games | ||

| Yes | 40 | 5.00% |

| No | 756 | 95.00% |

| Drinking Intentions | ||

| Did not intend to drink | 27 | 3.50% |

| Not enough to get buzzed | 55 | 7.10% |

| Slight buzz | 257 | 33.30% |

| A little drunk | 302 | 39.00% |

| Very drunk | 133 | 17.20% |

| Total Drinking Time | ||

| Mean (SD) | 773 | 259.39 (178.72) |

3.3. Individual-Level and Bar-Level predictors of BrAC

The results of the intercepts only-model are displayed in table 2. As noted earlier, there was significant variability for intoxication (BrAC) among patrons, both within groups as well as within bars. Bivariate regression analyses between level-1 predictors and BrAC (results not shown) yielded a set of 8 significant predictors (patron race, student status, total drinking time, drinking intentions, number of past 2-week heavy drinking episodes, pre-partying, playing drinking games, and plans to continue drinking). These variables were entered into a full single-level model and only the significant predictors of BrAC were retained for the final model.

Table 2.

Results of Hierarchical Linear Model Regression Modeling Level-1 and Level-2 Predictors of BrAC

| a. Intercepts-only model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Effect | Parameter | Standard | E Wald | p-value (or 95% Confidence Interval | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| 1-individual | Residual | 0.0017 | 0.0001 | 14.57 | <0.0001 | 0.0016 | 0.002 | |

| 2-groups | Intercept | 0.0009 | 0.0002 | 5.94 | <0.0001 | 0.0007 | 0.0013 | |

| 3-bars | Intercept | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | 2.53 | 0.006 | 0.0001 | 0.0006 | |

| b. Final Model Fixed Effects (Level-1) | ||||||||

| Level | Effect | Parameter | Standard | E t-value | Approx. | p-value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| 1-individual | Intercept | 0.0029 | 0.0056 | 0.51 | 237 | 0.61 | −0.0081 | 0.0138 |

| 1-individual | Pre-Partying | 0.0271 | 0.0042 | 6.52 | 711 | <0.001 | 0.0189 | 0.0353 |

| 1-individual | Drinking Intentions | 0.0195 | 0.0019 | 10.32 | 753 | <0.001 | 0.0157 | 0.0231 |

| 1-individual | Heavy Drinking | 0.0011 | 0.0005 | 2.05 | 728 | 0.041 | 0.0004 | 0.0021 |

| Model | −2 Log Likelihood df | X2 Difference | ||||||

| 1. Intercepts-only | 2616.127 | 4 | ||||||

| 2. Final Model | 2591.529 | 7 (M1–M2) 24.60* | ||||||

p<0.001

As shown in table 2, pre-partying, drinking intentions and number of heavy drinking episodes were significantly associated with patron BrAC. Specifically, pre-partying was associated with higher BrAC values. Both drinking intentions and number of past 2-week heavy drinking episodes were positively associated with intoxication. The final single-level model fit the data significantly better than the intercepts-only model, χ2 (3) = 24.60, p < 0.001. We next tested the three-level model which included all bar level covariates; however, none of these predictors were significant and the single-level model was retained as our final model.

3.4. Individual-Level and Bar-Level Predictors of BrAC Change

Table 3 shows the results of the intercepts-only model for the dependent variable of BrAC change (i.e., change in intoxication from bar entry to bar exit). The group and bar random effects were significant, indicating significant variance in BrAC values across groups and bars in the sample.

Table 3.

Results of Hierarchical Linear Model Regression Modeling Level-1 and Level-2 Predictors of BrAC Change

| a. Intercepts-only model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Effect | Parameter | Standard | E Wald | p-value (or 95% Confidence Interval | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| 1-individual | Residual | 0.0012 | 0.00008 | 15.15 | <0.0001 | 0.0011 | 0.0014 | |

| 2-groups | Intercept | 0.0005 | 0.00009 | 5.76 | <0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.0007 | |

| 3-bars | Intercept | 0.00007 | 0.00004 | 1.73 | 0.042 | 0.00002 | 0.0002 | |

| b. Final Model Fixed Effects (Level-1 and Level-3) | ||||||||

| Level | Effect | Parameter | Standard | E t-value | Approx. | p-value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| 1-individual | Intercept | −0.0144 | 0.0059 | −2.45 | 393 | 0.015 | −0.026 | −0.0029 |

| 1-individual | Gender | −0.0067 | 0.0029 | −2.28 | 709 | 0.023 | −0.0125 | −0.0009 |

| 1-individual | Drinking Intentions | 0.0066 | 0.0017 | 3.82 | 727 | <0.001 | 0.0032 | 0.0099 |

| 1-individual | Continue Drinking | 0.0141 | 0.0034 | 4.22 | 713 | <0.001 | 0.0076 | 0.0207 |

| 1-individual | Duration | 0.0003 | 0.00003 | 10.56 | 424 | <0.001 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 |

| 3-bar | Temp Bars | 0.0099 | 0.0046 | 2.17 | 30 | 0.038 | 0.0006 | 0.0192 |

| 3-bar | Dancing | −0.0111 | 0.0049 | −2.29 | 29 | 0.029 | −0.0211 | −0.0012 |

| Model | −2 Log Likelihood df | X2 Difference | ||||||

| 1. Intercepts-only | 2616.13 | 4 | ||||||

| 2. Final Model | 2591.53 | 7 (M1–M2) 24.60* | ||||||

p<0.001

The results of bivariate regression analyses examining the predictors of BrAC change (results not shown) yielded the following 6 significant predictors which were entered into a full single-level hierarchical model: patron gender, drinking intentions, pre-partying, heavy drinking episodes, plans to continue drinking and number of minutes spent in the bar. Results indicated gender, drinking intentions, plans to continue drinking and time spent in bar were all significant predictors of BrAC change. Pre-partying and number of past 2-week drinking episodes were not significant. The fit of the full single-level model was significantly better than the intercepts-only model, χ2 (6) = 313.72, p < 0.001.

We then tested a two-level model which included bar-level covariates but excluded non-significant level-1 predictors from the full model. Results showed that patron gender, drinking intentions, plans to continue drinking and time in bar remained significantly associated with BrAC change (Table 3). Significant positive increases in BrAC from bar entry to bar exit were observed for men and for participants who reported plans to continue drinking after leaving the bar. Additionally, intentions to get “really drunk” were positively associated with BrAC change. As would be expected, greater change in BrAC values were observed for patrons who spent more time in the bar, and therefore had a longer period to consume more alcoholic beverages. The results of the bar level predictors are also displayed in Table 3. Bars with patrons dancing were significantly associated with smaller changes in BrAC and a significant positive change in BrAC was associated with establishments that had temporary bars. Food availability and total drink price were not significant and were not included in the final model. The final three-level model did not fit the data better than single-level full model.

4. Discussion

This study examined the relationship among person-level characteristics, bar-level environmental characteristics and BrAC. At the person level, pre-partying, intent to get drunk and past two-week history of heavy episodic drinking were predictive of BrAC. BrAC change from entrance to exit of the bar was predicted by gender (male), drinking intentions (planned to get drunk), and time in the bar. In our final model, two environmental characteristics were associated with BrAC change from entrance to exit—the presence of dancing (protective) and temporary bars (risk).

4.1. Bar Level

At the bar level, it is important to note that over-service to our pseudo-patrons was almost a constant. Although studies have shown that responsible beverage service (RBS) can be effective (Saltz, 1997), more research is needed to see how such programs can be sustained and properly implemented. In San Diego County, bar staff and management receive RBS training each year (Novak, 2008). The over-service of our pseudo-patrons suggests that approaches that require servers to monitor the alcohol consumption of individual bar patrons may be less sustainable than other aspects of RBS training, such as not offering inexpensive drink specials.

Our findings concerning temporary bars and dancing have implications for prevention. On the protective side, encouraging bars with music to offer dancing might be a fairly easily environmental intervention to implement. Interestingly, other studies have found loud music in bars increases alcohol consumption (Gueguen et al., 2004; Gueguen et al., 2008). This effect seems to be moderated by dancing. Conversely, policies might be developed to preclude temporary point of sale bars in licensed establishments. We are uncertain whether the temporary bars we observed increased consumption of alcohol as a function of price, availability or both. More research is needed in this area.

4.2. Group Level

One of our more interesting findings is at the group level. As noted above, group level explained a significant amount (20%) of the variance in the dependent measure. The group level variables in our study (gender composition, size, mean age), however, did not explain any of this variance. Past studies on the relationship between group-size and drinking (Clark, 1982; Single, 1993) found that larger groups predicted heavier drinking. Hennessey and Saltz (1993), however, found that time spent in a bar, a variable included in our models, mediated this relationship. Future research might examine social group characteristics such as leadership, shared motivations, and competition. Further, it would be useful to measure how bar environments might influence group processes by introducing new members and/or subtracting original members (i.e., group cohesion).

4.3. Individual Level

When examining our individual-level findings in the final hierarchical models, being male, planning to continue to drink after leaving the bar, and time spent in the bar all contributed to BrAC change. Similarly, intentions to get drunk predicted a greater degree of BrAC change. These findings are consistent with past studies (Clapp et al., 2003; Cox and Klinger, 1988; Hennessy and Saltz, 1993) and illustrate the importance of further examining person-level characteristics in future ecological studies. One area that was fairly limited in the present study was our measure of motivations. Future studies would benefit from standard general measure of drinking motivations (The Copper Scale for instance) and the inclusion of exploratory event specific motivations.

Interventions aimed at shifting such motivations (individual level) might include increasing the perception of risk for problems (i.e., DUI) using media campaigns (Clapp et al., 2005) or employing brief interventions in the field (Lange et al., 2006). Such interventions, coupled with environmental manipulations like those described above, might mitigate such intentions. Again, developmental and evaluative research in this area is needed.

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

This study examined the relationship between environmental characteristics of bars and estimates of blood alcohol concentrations. The study is unique in that it employed both observational measures of the bar, patron interviews, and collected breath samples. Such designs have ecological validity, in that they likely reflect the “real world” better than laboratory or retrospective survey based research. The design of the present study, however, has some limitations which illustrate the challenges associated with such research. First, pre-bar drinking environments were measured using self-reports; however, having a BrAC measure upon entrance mitigates problems with self-reports of alcohol use. Another limitation is that we were unable to capture multiple pre-bar drinking environments across one evening or establish a detailed sequence of drinking behavior in multiple environments. Studies that use time and location sampling might help address this issue. We encountered the same limitations with intentions to drink after leaving the bar. Additionally, we were unable to track respondents to determine whether the drinking episode was linked to any subsequent alcohol-related problems (e.g., DUI, illness, regretted sex, etc.). Ecological momentary assessment studies might yield such information.

In sum, among bar patrons, drinking behavior within a night-time single episode appears to occur in multiple contexts with numerous risk and protective factors. The complexity of such episodes and the environments in which they occur represent person and environment interactions that might be amenable to prevention efforts. As such, this study was a preliminary effort to better understand the nature of alcohol intoxication in dynamic settings.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (RO1 AA013968, Dr. Clapp, PI). The funding source had no involvement in the study design, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of this report, or in the decision to submit this paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bot SM, Engels RCME, Knibbe RA, Meeus WHJ. Pastime in a pub: observations of young adults’ activities and alcohol consumption. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:491. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavan S. Liquor License: An Ethnography of Bar Behavior. Aldine Chicago: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Holmes MR, Reed MB, Shillington AM, Freisthler B, Lange JE. Measuring college students’ alcohol consumption in natural drinking environments: field methodologies for bars and parties. Evaluation Review. 2007;31:469. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07303582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Johnson M, Voas RB, Lange JE, Shillington A, Russell C. Reducing DUI among US college students: results of an environmental prevention trial. Addiction. 2005;100:327. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Lange J, Min JW, Shillington A, Johnson M, Voas R. Two studies examining environmental predictors of heavy drinking by college students. Prevention Science. 2003;4:99–108. doi: 10.1023/a:1022974215675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Min JW, Shillington AM, Reed MB, Ketchie Croff JM. Person and Environment Predictors of Blood Alcohol Concentrations: A Multi-Level Study of College Parties. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:100–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Reed MB, Holmes MR, Lange J, Voas R. Drunk in Public, Drunk in Private: The Relationship between College Students’ Drinking Environments and Alcohol Consumption. American Journal of Drug & Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:275–285. doi: 10.1080/00952990500481205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Shillington AM, Segars LB. Deconstructing contexts of binge drinking among college students. American Journal of Drug & Alcohol Abuse. 2000:139. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark WB. Public drinking contexts: Bars and taverns. In: Harford TC, Gaines LS, editors. Research Monograph No 7: Social Drinking Contexts; Proceedings of a Workshop September 17 – 19, 1979; Washington DC. Washington D.C.: Department of Health and Human Services; 1982. pp. 8–33. [Google Scholar]

- Coate D, Grossman M. EFFECTS OF ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE PRICES AND LEGAL DRINKING AGES ON YOUTH ALCOHOL USE. Journal of Law & Economics. 1988;31:145–172. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Anderson P, Babor TF, Casswell S, Ferrence R, Giesbrecht N, Godfrey C, Holder HD, Lemmens P, Makela K, Midanik LT, Norstrom T, Osterberg E, Romelsjo A, Room R, Simpura J, Skog O-J. Alcohol Policy and the Public Good. Oxford University Press; New York: 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines LS. DHHS 81–1097. Washington DC: 1982. Social Drinking Contexts. [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Osgood D, Zibrowski E, Purcell J, Gliksman L, Leonard K, Pernanen K, Saltz RF, Toomey TL. The effect of the Safer Bars programme on physical aggression in bars: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2004;23:31–41. doi: 10.1080/09595230410001645538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Room R. Situational norms for drinking and drunkenness: trends in the US adult population, 1979–1990. Addiction. 1997;92:33–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ. The spatial ecology of alcohol problems: niche theory and assortative drinking. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2007;102:870–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ, Millar AB. Alcohol availability and the ecology of drinking behavior. Alcohol Health & Research World. 1993;17:39. [Google Scholar]

- Gueguen C, LeGuellec J, LeGuellec H. Sound level and background of music and consumer behavior: An empiricial evaluation. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2004;99:134–136. doi: 10.2466/pms.99.1.34-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueguen N, Jacob C, Le Guellec H, Morineau T, Lourel M. Sound level of environmental music and drinking behavior: a field experiment with beer drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1795–1798. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusfield JR. Managing competence: An ethnographic study of drinking-driving and the context of bars. In: Harford TC, Gaines LS, editors. Research Monograph No 7: Social Drinking Contexts; Proceedings of a workshop; September 17 – 19, 1979; Washington, DC. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1982. pp. 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC. Contextual Drinking Patterns Among Men and Women. Currents in Alcoholism. 1979;4:287–296. [Google Scholar]

- Harford TC, Gaines LS. Social Drinking Contexts: An Introduction. In: Harford TC, Gaines LS, editors. Research monograph No7. Superintendent of Documents; Social drinking contexts: Proceedings of a workshop; Washington DC. September 17–19, 1979; Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1979. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy M, PhD, Saltz RF., PhD Modeling Social Influences on Public Drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:139–145. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder HD, Saltz RF, PhD, Treno AJ, Grube JW, Voas RB., PhD Evaluation Design for a Community Prevention Trial: An environmental approach to reduce alcohol-involved trauma. Evaluation Review. 1997;21:140–165. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9702100202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovell MF, Wahlgren DR, Gehrman CA. The Behavioral Ecological Model: Integrating Public Health and Behavioral Science. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Keglar MC, editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research: Strategies for Improving Public Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2002. p. 414. [Google Scholar]

- Howard-Pitney B, Johnson MD, Altman DG, Hopkins R, Hammond N. Responsible alcohol service: a study of server, manager, and environmental impact. American Journal Of Public Health. 1991;81:197. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Engels R, Gmel G. Drinking Motives as Mediators of the Link Between Alcohol Expectancies and Alcohol Use Among Adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:76. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Paschall MJ, Maclennan B, Langley JD. Intoxication by drinking location: A web-based diary study in a New Zealand university community. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2586–2596. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang E, Stockwell T, Rydon P, Lockwood A. Drinking settings and problems of intoxication. Addiction Research Vol 3(2) Nov. 1995;1995:141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lange JE, Reed MB, Johnson MB, Voas RB. The efficacy of experimental interventions designed to reduce drinking among designated drivers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:261–268. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight AJ, Voas RB. The effect of license suspension on DWI recidivism. Alcohol, Drugs, and Driving. 1991;7:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Novak M. Conversation about Responsible Beverage Service. San Diego: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Okraku IO. Tavern-going in America: A causal analysis. Leisure Sciences. 1998;20:303. [Google Scholar]

- Saltz RF., PhD Evaluating Specific Community Structural Changes: Examples from the assessment of Responsible Beverage Service. Evaluation Review. 1997;21:246–267. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9702100207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Single E. Public drinking. In: Galanter M, Begleiter H, Deitrich R, Gallant D, Goodwin D, editors. Recent Developments in Alcoholism, Vol 11: Ten Years of Progress. Plenum Press; New York: 1993. pp. 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell T, Lang E, Rydon P. High risk drinking settings: The association of serving and promotional practices with harmful drinking. Addiction. 1993;88:1519–1526. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb03137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. Creating health-promotive environments: implications for theory and research. In: Jamner MS, Stokols D, editors. Promoting Human Wellness: New Frontiers for Research, Practice, and Policy. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2000a. p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. Social ecology and behavioral medicine: implications for training, practice, and policy. Behav Med. 2000b;26:129–138. doi: 10.1080/08964280009595760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. Allyn & Bacon; Boston: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Dodd V, Pokorny SB, Omli MR, O’Mara R, Webb MC, Lacaci DM, Werch C. Drink specials and the intoxication levels of patrons exiting college bars. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2008a;32:411–419. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.4.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, Dodd V, Pokorny SB, Omli MR, O’Mara R, Webb MC, Lacaci DM, Werch C. Drink specials and the intoxication levels of patrons exiting college bars. Am J Health Behav. 2008b;32:411–419. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.4.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Goor I, Knibbe RA, Drop MJ. Adolescent drinking behavior: An observational study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1990;51:548–555. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H. Change. 1996. Alcohol and the American College Campus: A report from the Harvard School of Public Health; pp. 20–25.pp. 60 [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Kuo M, Lee H, Dowdall GW. Environmental correlates of underage alcohol use and related problems of college students. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000a;19:24–29. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990s: a continuing problem. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. Journal of American college health: J of ACH. 2000b;48:199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American college health: J of ACH. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westmaas J, Moeller S, Woicik PB. Validation of a measure of college students’ intoxicated behaviors: associations with alcohol outcome expectancies, drinking motives, and personality. Journal of American College Health. 2007;55:227–237. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.4.227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]