Abstract

Disruption to endochondral ossification leads to delayed and irregular bone formation and can result in a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders known as the chondrodysplasias. One such disorder, multiple epiphyseal dysplasia (MED), is characterized by mild dwarfism and early-onset osteoarthritis and can result from mutations in the gene encoding matrilin-3 (MATN3). To determine the disease mechanisms that underpin the pathophysiology of MED we generated a murine model of epiphyseal dysplasia by knocking-in a matn3 mutation. Mice that are homozygous for the mutation develop a progressive dysplasia and have short-limbed dwarfism that is consistent in severity with the relevant human phenotype. Mutant matrilin-3 is retained within the rough endoplasmic reticulum of chondrocytes and is associated with an unfolded protein response. Eventually, there is reduced proliferation and spatially dysregulated apoptosis of chondrocytes in the cartilage growth plate, which is likely to be the cause of disrupted linear bone growth and the resulting short-limbed dwarfism in the mutant mice.

INTRODUCTION

Chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation within the cartilage growth plate of endochondral bones is the driving force behind longitudinal bone growth. For example, chondrocyte proliferation and matrix deposition in the growth plate is the basis of long bone growth, while apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes plays a pivotal role in the transition from chondrogenesis to osteogenesis (1). The regulation and control of chondrocyte proliferation, hypertrophy and apoptosis in the relevant zones of the growth plate is therefore critical for normal bone growth (2,3) and any disruption to the balance between proliferation and hypertrophy can lead to skeletal defects and in particular the chondrodysplasias (4).

The chondrodysplasias are a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of diseases that affect the development of the skeleton (5). There are over 200 different phenotypes, which range in severity from relatively mild to severe and lethal forms. Although individually rare, as a group of diseases the chondrodysplasias have an overall incidence of at least 1 per 4000 and result in a significant healthcare responsibility.

Many of the individual phenotypes have been grouped into ‘bone dysplasia families’ on the basis of a similar clinical and radiographic presentation and members of the same family are postulated to share common disease mechanisms (6). Pseudoachondroplasia (PSACH) and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia (MED) are a family of autosomal dominant skeletal dysplasias, which share common phenotypic characteristics but encompass a wide spectrum of severity, ranging from severe to mild phenotypes, respectively (7,8). PSACH results exclusively from mutations in the gene encoding cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) (9), the fifth member of the thrombospondin protein family. Some forms of MED are allelic with PSACH and also result from COMP mutations, however, MED is genetically heterogeneous and can also result from mutations in the genes encoding matrilin-3 (MATN3) and collagen type IX (COL9A1, COL9A2 and COL9A3) (7). A recessive form of MED is caused by mutations in the sulphate transporter 26A2 protein (SLC26A2/DTDST) (10). Matrilin-3, COMP and type IX collagen are all expressed extensively in a range of skeletal tissues, but in particular throughout the cartilage growth plate during endochondral ossification (11-14).

The matrilins are a family of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins; matrilin-1 and matrilin-3 are specifically expressed in cartilaginous tissues while matrilin-2 and matrilin-4 have a wider pattern of expression in a variety of ECMs including non-skeletal tissues (15). Matrilin-3 comprises a single von Willebrand factor A-like domain (A-domain), four EGF-like motifs and a coiled-coil oligomerization domain. Matrilin-3 can form hetero-oligomers with matrilin-1 (16,17) and has been shown to bind to COMP and collagen types II and IX in vitro (18,19).

All of the MED mutations identified in MATN3 are missense mutations which primarily affect conserved residues that comprise the β-sheet of the single A-domain of matrilin-3 (20-22); although a single missense mutation has also been identified in the α-1 helix of the A-domain (23). Interestingly, a missense mutation (p.Thr303Met) in the first EGF-domain of matrilin-3 has been implicated in susceptibility to hand osteoarthritis (24,25) and spinal disc degeneration (26) suggesting a role for MATN3 mutations in the pathophysiology of more common cartilage-related diseases (27).

Previous studies of MATN3 mutations using transfected cells as an in vitro assay have suggested that mutant matrilin-3 is retained within the rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER) of chondrocytes (22,28), where it exists as an unfolded intermediate and is associated with ERp72 (22), a chaperone protein known to be involved in mediating disulphide bond formation (29). Although in vivo data is very limited, due primarily to the scarcity of relevant samples, the microscopic analysis of an iliac crest biopsy from a 10-year old boy with MED, caused by a p.Arg121Trp mutation in matrilin-3, shows evidence of enlarged cisternae of rER due to the retention of matrilin-3 (22). In this context, the consequences of MATN3 mutations on the trafficking of matrilin-3 appear similar to those caused by COMP mutations in MED and PSACH (8). For example, mutations in the type III repeats of COMP have been shown to cause the retention of mutant COMP in enlarged cisternae of rER, along with the co-retention of other ECM molecules. This accumulation of protein has been proposed to elicit a cell stress response and results in an apparent increase in apoptosis (30-35).

However, the over reliance on in vitro expression systems to study the effects of MATN3 and COMP mutations has meant that fundamental questions concerning the effect of mutant protein expression on chondrocyte proliferation and apoptosis in the growth plate have remained unresolved. Although a series of knock-out mice have been generated for COMP (36) and the matrilin family of ECM proteins, such as matrilin-3 (37), matrilin-1 (38,39) and matrilin-2 (40), all of these mice have apparently normal skeletal development. More recently, a second matrilin-3-deficient mouse strain was shown to have premature chondrocyte maturation, increased bone mineral density and osteoarthritis, but no chondrodysplasia (41). Overall, these data indicate a functional redundancy within the matrilin and thrombospondin families of proteins and strongly suggest that PSACH and MED are caused by dominant-negative (antimorphic) mechanisms. In order to determine in vivo the disease mechanisms that underlie the pathophysiology of MATN3 mutations we have generated a murine model of MED by introducing a specific human disease-causing mutation (p.Val194Asp) into the A-domain of mouse matrilin-3.

RESULTS

Generation of a matn3 (p.Val 194Asp) knock-in mouse model of chondrodysplasia

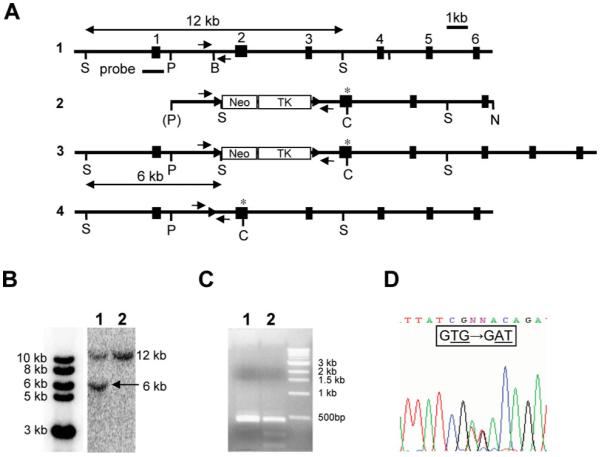

Mice harbouring the equivalent of the human p.Val194Asp mutation in the A-domain of matrilin-3 were generated by homologous recombination in R1 ES cells (Fig. 1A). The GTG → GAT mutation was introduced into exon 2 of matn3 by site-directed mutagenesis. Of 360 ES clones, 33 tested positive for homologous recombination by Southern blotting using the external probe on SpeI digested genomic DNA (Fig. 1B). Twenty-two of which also contained the desired mutation shown by ClaI digestion and direct DNA sequencing (Fig. 1C and D). Six correctly targeted clones were then transiently transfected with the pIC-Cre vector and the deletion of the neo-tk selection cassette in FIAU-resistant ES clones was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis. ES cells from one clone were then used to generate chimeric mice. High contribution chimeric males were mated with C57BL/6 females to generate F1 heterozygote offspring. Further crosses generated mice that were either heterozygous or homozygous for the p.V194D mutation. Normal Mendelian ratios were observed in the offsprings of all matings.

Figure 1.

Generation of the matn3 p.Val194Asp knock-in mouse model. (A) 1: genomic organization of the mouse matn3 gene; individual exons are indicated by black boxes and numbered sequentially. 2: the targeting construct with LoxP sequences indicated by arrowheads and the site of the mutation by an asterisk. Neo, neomycin resistance cassette; TK, thymidine kinase gene. 3: the homologous recombinant allele and 4: the recombinant allele after cre transfection. Relevant restriction sites are: S, SpeI; P, Psp OMI; B, BamHI; C, ClaI; N, NotI. Probe denotes the external probe used in Southern blot detection of wild-type and homologously recombined mutant matn3 alleles. (B) Southern blot analysis of transfected ES cells. The probe indicated in (A) detects a 12 kb fragment and 6 kb fragment after digestion with SpeI in the wild-type and knock-in alleles, respectively; 1, homologous recombinant; 2, wild-type alleles. (C) PCR amplification of the region containing the mutation was followed by digestion with ClaI. The p.Val194Asp mutation introduces a ClaI restriction site and mutation-positive homologously recombinant clones show the presence of two extra digestion products (1, wild type; 2, homologous recombinant). (D) Sequencing of mutation-positive homologous recombinants confirmed the presence of the mutation (GTG > GAT). Small arrows show the location of primers used for routine genotyping.

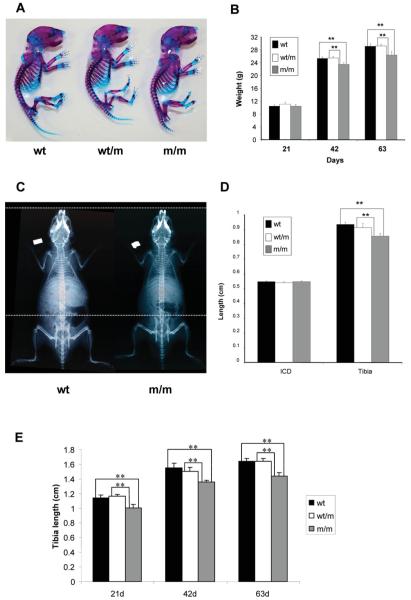

Knock-in mice are normal at birth but develop short-limbed dwarfism

At birth the skeletons of mice heterozygous or homozygous for the p.Val194Asp mutation appeared normal when compared with wild-type littermates (Fig. 2A). At day 21 all mice had similar body weights, however, by day 42 mice that were homozygous for the mutation were approximately 7.5% lighter than either their wild-type or heterozygous littermates and by day 63 these same mice were approximately 9.5% lighter [Fig. 2B; n > 23 mice per genotype, **P < 0.01 by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)]. The body weights of mice heterozygous for the mutation were indistinguishable from those of their wild-type littermates.

Figure 2.

Phenotypic characterization of wild type mice and mice either heterozygous or homozygous for the matn3 p.Val194Asp mutation. (A) Alcian blue (cartilage) and Alizarin red (bone) staining of whole newborn skeletons. There is no overt phenotype observed in mice heterozygous (wt/m) or homozygous (m/m) for the mutation. (B) Mouse growth curves. All mice have normal body weights at day 21, but from day 21 onwards the growth of m/m mice is reduced when compared with both wt and wt/m mice eventually leading to a 9.4% reduction in body weight by day 63 (n > 23 mice per genotype, **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA). (C) Radiographs of day 42 wild-type mice and mice homozygous for p.Val194Asp, confirm that mice homozygous for the mutation are shorter than the wild-type mice. White dotted lines are aligned at the tip of the nose and the top of the pelvis of the m/m mouse. (D) Bone length measurements of the inner canthal distance (ICD) and the tibia from 14-day-old male mice demonstrate reduced long bone growth when compared with wt littermates (n > 6 mice, **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA). (E) Bone length measurements of the tibia at 21, 42 and 36 days of age. A maximum reduction of approximately 12.5% was seen by 21 days of age (n > 6 mice, **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA). Similar reductions in bone length were also recorded for the humerus, pelvis and femur (data not shown). At all time points there was no statistical difference between the respective ICD for all three genotypes.

Bone length measurements were performed on mice of all three genotypes at days 14, 21, 42 and 63. Bone measurements were made of the inner canthal distance (ICD), a measure of intramembranous bone growth; and of the humerus, pelvis, femur and tibia, as measures of endochondral bone growth (Fig. 2C, D and E; only ICD and tibia measurement are shown but the results are representative of all bones measured). At day 14 mice that were homozygous for the mutation had tibia lengths that were approximately 8.5% shorter than both their wild-type and heterozygous littermates (Fig. 2D) and by day 21 the reduction in tibia lengths had progressed to approximately 12.5% (Fig. 2E; n > 6 mice per genotype, **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA). No differences were observed in the ICD of age-matched mice of all three genotypes at all ages confirming that intramembranous bone growth was not affected by the matn3 mutation (Fig. 2D and E). These morphometric measurements demonstrated that mice, which are homozygous for p.Val194Asp, are normal at birth but from day 14 develop a measurable short-limbed dwarfism as a result of disturbed endochondral ossification. The age of onset and progressive nature of the dwarfism in mutant mice is comparable to the age of onset in patients with MED, which can be as early as 2 years of age.

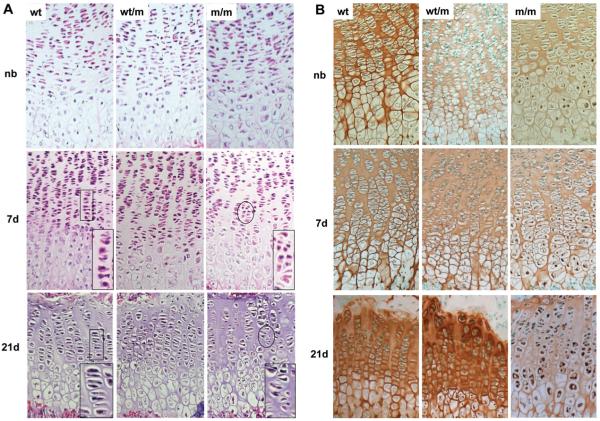

The cartilage growth plate is disorganized in mice harbouring the matn3 mutation

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the tibia growth plates from wild-type animals at all ages showed a well organized growth plate in which the resting, proliferative and hypertrophic zones were clearly distinguishable (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the cells in the proliferative zone were closely aligned in well-ordered columns that were evenly spaced along the horizontal axis of the growth plate. The tibia growth plates from mice homozygous for the matn3 mutation also appeared normal at birth. However, from day 7 mice that were homozygous for the mutation developed a progressively dysplastic growth plate in which the proliferative zone had a disordered cellular organization and morphology (Fig. 3A: inset). This dysplasia was also seen in the hypertrophic zone but no growth plate dysplasia was evident in mice that were heterozygous for the mutation.

Figure 3.

Histological and immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of the tibia growth plate shows disrupted growth plate morphology and retention of mutant matrilin-3 protein. (A) H&E staining of newborn (NB), 7- and 21-day-old tibia growth plates of wild-type (wt) mice and of mice either heterozygous (wt/m) or homozygous (m/m) for the mutation (PFA-fixed 6 μm sections). The growth plates of new born mice show no overt dysplasia. However, from day 7 and, in particular, at day 21 m/m mice have a disrupted proliferative zone with disorganized columns (insert) and some areas of hypocellularity. (B) IHC using an anti-matrilin-3 antibody on NB, day 7 and 21 tibia growth plates from wt, wt/m and m/m mice (ethanol/acetic acid-fixed 6 μm sections). Chondrocytes in the hypertrophic zone of NB mice homozygous for the mutation show the retention of mutant matrilin-3. By day 7 this retention is more widespread and affects all zones of the growth plate. By day 21 the retention of matrilin-3 has become more extensive and there are significantly reduced levels of staining in the matrix. By day 21 mice heterozygous for the mutation are also exhibiting low-levels of matrilin-3 retention but the amount of matrilin-3 in the ECM appears to be within normal limits.

The retention of mutant matrilin-3 within the rER of chondrocytes is observed from birth

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of tibia cartilage from newborn wild-type mice showed that matrilin-3 was present throughout the ECM of the growth plate and by day 21 had a predominantly territorial localization. In contrast, analysis of cartilage from newborn mice that were homozygous for the matn3 mutation demonstrated that while matrilin-3 was present in the ECM, there were also detectable levels retained within the pre-hypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes (Fig. 3B). By day 7 the retention of matrilin-3 had become more widespread and was present in chondrocytes from all zones of the growth plate. Finally, by day 21 the retention of mutant matrilin-3 was extensive and the levels of secreted protein were markedly reduced. In contrast, chondrocytes from mice that were heterozygous for the mutation showed no apparent retention of matrilin-3 until day 21 and at this age it was only present in hypertrophic chondrocytes (Fig. 3B). IHC analysis using anti-matrilin-1, -COMP, -collagen II, -collagen IX, -collagen X, -aggrecan, revealed no apparent disruption to the localization of these proteins in the ECM of mice homozygous for the mutation (Supplementary data).

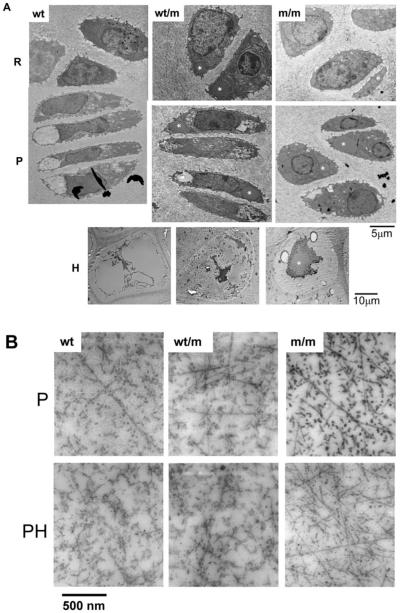

Ultrastructural analysis of the growth plate cartilage revealed enlarged individual cisternae of rER within the chondrocytes and disrupted chondron organization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed along the entire vertical axis of the growth plate to generate a complete montage of the cartilage growth plate of a 7-day-old mouse tibia (i.e. from resting to terminal hypertrophic and mineralization zones). By aligning images it was possible to compare directly the ultrastructure of a wild-type mouse with littermates that were either heterozygous or homozygous for the mutation (Fig. 4A). In the wild-type growth plate the resting chondrocytes were evenly spaced, while in the early to late proliferative zones, groups of flattened cells (i.e. 2, 4 and 8 cells per chondron) were apparent. The morphology of chondrocytes in the growth plate of mice that were homozygous for the mutation was strikingly different. For example, chondrocytes in the resting zone contained numerous dilated cisternae of rER in addition to the normal rER. These dilated cisternae gradually become larger in size as the chondrocytes underwent proliferation and in some cells they occupied large sections of the cytoplasm, indeed there was a proportion of the proliferating chondrocytes that were ‘wedge-shaped’ in appearance and were unable to align closely within the 4 and 8 cell chondrons. All chondrocytes in the growth plate of mutant mice (n > 200) showed enlarged dilated cisternae of rER, which was not seen in chondrocytes from wild-type mice. Most chondrocytes from mice heterozygous for the mutation had some distended rER, but this was not as prominent as that seen in homozygous mice.

Figure 4.

Ultrastructural analysis of 7-day-old tibia growth plates from wild-type mice, and from mice either heterozygous or homozygous for the mutation, shows enlarged individual cisternae of rER and altered chondrocyte morphology in mutant mice. (A) This representative selection of images was taken from a complete TEM montage of a day 7 tibia growth plate (from resting to mineralization zones). Resting (R), proliferative (P) and hypertrophic (H) zones are shown. Chondrocytes in the R zone of m/m mice show enlarged individual cisternae of rER (asterisk). In the P zone the enlarged cisternae are more widespread within individual chondrocytes. Chondrocytes from wt/m mice show evidence of dilated cisternae of rER (asterisk), but the overall morphology of the chondrocytes appears within normal limits. Scale bar = 5 μm (R and P) or 10 μm (H). (B) TEM of the inter-territorial matrix of the proliferating (P) zone and the prehypertrophic (PH) zone of day 7 tibia growth plates. The extracellular matrix (ECM) in the proliferating zone from wt mice shows collagen fibrils with high levels of surface-associated proteins. The fibrils in m/m mice appear to have less surface coating. Samples of wt/m are similar in appearance to wt. Scale bar = 500 nm.

Hypertrophic chondrocytes from wild-type mice were somewhat rectangular in shape and the condensation of chromatin was clearly apparent (42). In contrast, hypertrophic chondrocytes from mice homozygous for p.Val194Asp mutation were more oval in shape and showed the persistence of protein within the remnants of the rER (Fig. 4A).

There is a disturbance to collagen networks in the mutant growth plate

TEM analysis of the inter-territorial matrix from the proliferating and pre-hypertrophic zones of day 7 tibia growth plates was used to study the ECM architecture of the growth plate cartilage (Fig. 4B). The growth plate cartilage in wild-type mice contained multiple randomly arranged collagen fibrils, but individual fibrils were not always apparent because of a coating of stained proteins (e.g. proteoglycans) (43). In contrast, the collagen fibrils in the ECM of mice homozygous for the mutation were readily identified by their uniform diameter and banding pattern. The differences between collagen fibrils in wild-type and mutant ECM was most apparent when the fibrils were in transverse section (i.e. cut end-on), when the fibrils appeared as dense circles. For example, in the proliferative zone, the mutant samples showed high contrast between the fibril surface and the inter-fibrillar space, whereas in wild-type the abundance of fibril-associated material blurred the fibril boundaries. This effect was most pronounced in the pre-hypertrophic zone; in the mutant samples the fibrils are readily seen whereas in the wild-type, the presence of surface-associated material obscured virtually all of the fibril cross-sections.

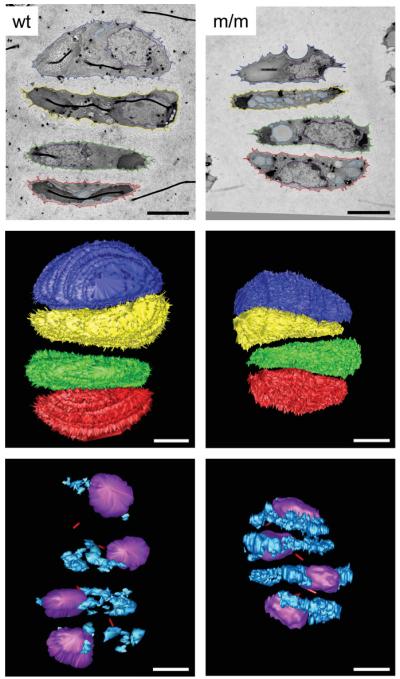

Three-dimensional reconstruction of 4-cell chondrons shows a 9-fold increase in the volume of distended rER in chondrocytes from mutant mice

Three-dimensional reconstructions of 140 serial TEM sections from the tibia of wild-type and mutant mice at day 7 were used to generate virtual representations of 4-cell chondrons from the proliferative zone of the growth plate (Fig. 5 and supplemental video). In the wild-type mice the volume of the rER, expressed as a proportion of the total cell volume, was 1.3% per individual chondrocytes (average 7.28 μm3/549.25 μm3 cell volume; n = 4). However, in mutant mice the average volume of the distended rER per individual chondrocyte was 11.6% (average 55.3 μm3/476.5 μm3 cell volume; n = 4), thus representing an approximately 9-fold increase in the volume of the rER (Fig. 5 and supplemental video).

Figure 5.

Chondrocytes from mice homozygous for the mutation have increased distended rER volume. Serial section reconstructions of cells (day 7) from wild-type mice and mice homozygous for the mutation were performed to obtain a three-dimensional virtual representation of a 4-cell chondron. From this model morphological differences were assessed, in particular calculations were made regarding chondrocyte (549.25 μm3/chondrocyte for wild-type and 476.5 μm3/chondrocyte for mutant), nuclei (76.5 μm3/chondrocyte for wild-type and 94 μm3/chondrocyte for mutant) and distended rER volumes (7.3 μm3/chondrocyte for wild-type and 55.3 μm3/chondrocyte for mutant). The top panel shows a representative TEM image from the serial sections of wild-type and mutant growth plate. The colours show the tracing of different cell structures and relate to the reconstruction. The middle panel shows the three-dimensional reconstruction of the 4-cell chondrons from wild-type and mutant mice [chondrocyte 1 (articular surface side): blue, chondrocyte 2: yellow, chondrocyte 3: green, chondrocyte 4: red (trabecular bone side)]. The bottom panel shows the internal structure of the chondrocytes. There is a visible increase in the amount of distended rER in the chondrocytes from mutant mice (nuclei: purple; distended rER: pale blue; primary cilia tube: red). Scale bar = 5 μm.

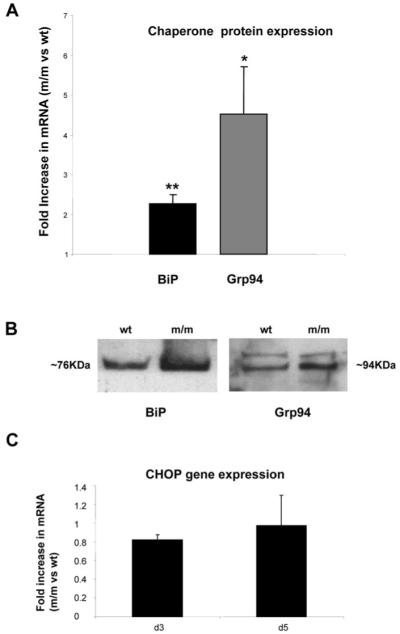

Chaperone proteins associated with the unfolded protein response are upregulated in mutant chondrocytes

The increased expression of the rER chaperones BiP and Grp94 are classical markers of an unfolded protein response activation in both yeast and mammalian cells (44-46). Therefore, to determine if the retention of mutant matrilin-3 was eliciting an unfolded protein response we performed quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), western blot analysis and IHC to evaluate the relative levels of these chaperone proteins in the chondrocytes of wild-type mice and mice homozygous for the mutation. qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that by 3 days of age the relative levels of BiP and Grp94 were upregulated in mutant chondrocytes by >2- and >4-fold, respectively (Fig. 6A; n = 3 samples per genotype, independent t-test **P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, respectively), which was confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. 6B; n = 6 samples per genotype) and IHC (not shown).

Figure 6.

The accumulation of mutant matrilin-3 elicits an unfolded protein response in chondrocytes. (A) mRNA levels of the UPR-associated chaperones (BiP and GRP94; see methods for primer sequences) were determined using qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA isolated from mutant and wild-type chondrocytes at day 4. The graph indicates the relative increase in levels of mRNA in mutant chondrocytes when compared with wild-type chondrocytes and in both cases the level of mRNA was normalized against 18s RNA. BiP and Grp94 mRNA levels were >2- and >4-fold increased, respectively in mutant mice [n = 3 mice; three separate experiments in duplicate, independent t-test, P < 0.05 (*) or P < 0.01 (**)]. (B) Total cellular protein isolated from equal numbers of wild-type or mutant chondrocytes (2 × 105 cells) was analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot using antibodies raised against BiP (approximately 76 kDa) and Grp94 (approximately 94 kDa), the anti-Grp94 antibody consistently detected an non-specific band. Protein levels of both chaperones were elevated in mice homozygous for the mutation at day 4. (C) The relative levels of CHOP mRNA in mutant chondrocytes was determined by qRT-PCR. At day 3 and 5 there was no obvious upregulation of CHOP expression in mutant chondrocytes when compared with wild-type (n = 3 mice per genotype; three separate experiments, independent t-test).

When misfolded/unfolded mutant proteins accumulate in the rER they can induce an unfolded protein response, which may cause rER/cell stress and the increased expression of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP/GADD153) (47). CHOP is a member of the C/EBP family of bZIP transcription factors and because its over expression induces apoptosis we investigated the relative levels of CHOP expression in mutant chondrocytes by qRT-PCR. However, at 3, 5 and 21 days of age there was no detectable increase in the relative levels of CHOP expression compared with wild-type chondrocytes (Fig. 6C).

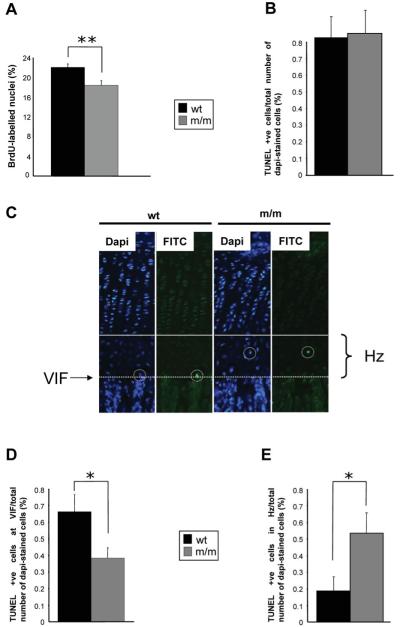

Mice homozygous for the mutation have reduced chondrocyte proliferation in the growth plate

In order to understand the physiological effect of upregulated chaperone protein expression and the unfolded protein response on chondrocyte differentiation and eventually longitudinal bone growth we determined the relative levels of chondrocyte proliferation in the growth plate. To quantify the levels of chondrocyte proliferation in the growth plate BrdU labelling experiments were performed at day 21. Within the proliferative zone of wild-type mice, 22% of cell nuclei were labelled with BrdU, while only 18% of nuclei were labelled within the proliferative zone of mice homozygous for the mutation, thus signifying an overall decrease of 16% in the rate of chondrocyte proliferation (Fig. 7A; n > 36 sections from >3 mice per genotype, independent t-test **P < 0.01). Proliferation rates in mice heterozygous for the mutation were comparable to those of wild-type mice (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Cell proliferation and apoptosis are significantly affected in the mutant growth plate. (A) Twenty-one day old mice were administered with 0.01 ml/g of the nucleotide analogue BrdU 2 h prior to sacrifice. Tibia samples from mice were processed as normal and IHC was performed using anti-BrdU antibody on ethanol-fixed 6 μm sections. The proportion of BrdU-labelled nuclei was calculated by comparing the number of BrdU-labelled nuclei with the total number of chondrocytes in the proliferating zone (i.e. methyl green-labelled nuclei + BrdU-labelled nuclei). Mice homozygous for the matn3 p.V194D mutation had significantly lower proliferation rates when compared with wild-type and heterozygote mice (n > 36 section per genotype, independent t-test, **P < 0.01). End-stage apoptosis (DNA fragmentation) was measured in the tibia of 21-day-old mice (PFA-fixed 6 μm sections) using the DeadEnd™ fluorometric TUNEL system. (B) The relative levels of apoptosis were calculated by comparing the number of apoptotic chondrocytes (FITC-labelled nuclei) with the total number of chondrocytes in the hypertrophic zone (DAPI-labelled nuclei + FITC-labelled nuclei). (C) Representative images of tibia growth plates showing DAPI and FITC stained sections. White circles highlight TUNEL-positive chondrocytes while the solid line indicates the start of the hypertrophic zone and the dotted line marks the VIF. Apoptosis was occurring away from the VIF in mice homozygous for the mutation. (D) The rate of apoptosis at the VIF for mice homozygous for the mutation was 0.38% when compared with 0.66% for wild-type mice; an overall reduction of >40% (E) Apoptosis of chondrocytes in the hypertrophic zone was significantly increased in mutant mice (n > 20 sections per genotype, independent t-test, **P < 0.05).

Chondrocyte apoptosis is spatially dysregulated in the growth plates of mutant mice

To determine if the unfolded protein response was having a detrimental effect on cell viability we determined the relative levels of apoptosis in the growth plate at 21 days of age by counting the number of TUNEL-positive cells when compared with DAPI-stained cells in the hypertrophic zone. In both the wild-type and mutant growth plates, approximately 0.8% of cells were TUNEL-positive which was within normal limits (48) (Fig. 7B; typically two to three TUNEL-positive cells from 285 to 310 DAPI-stained cells per section, n > 20 sections from >3 mice per genotype). However, we noticed that in the mutant growth plate, unlike wild-type mice, that apoptosis was occurring throughout the hypertrophic zone and was not just limited to terminal hypertrophic chondrocytes at the vascular invasion front (Fig. 7C). For example, in the wild-type growth plate apoptosis was mostly restricted to terminal hypertrophic chondrocytes at the vascular invasion front and typically approximately 0.7% of TUNEL-positive cells were specifically located at the vascular invasion front. In contrast, only 0.38% of TUNEL-positive cells were located at the vascular invasion front in mice homozygous for the mutation (Fig. 7D; n > 20 sections from >3 mice per genotype, independent t-test *P < 0.05). Furthermore, the relative number of TUNEL-positive cells throughout the entire hypertrophic zone (i.e. upper → lower hypertrophic zones) was significantly increased in the mutant growth plate, suggesting that apoptosis was spatially dysregulated (Fig. 7E; n > 20 sections from >3 mice per genotype, independent t-test *P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this study we have generated a knock-in mouse model to determine the disease mechanisms that underpin the pathophysiology of MED caused by a matrilin-3 mutation. We introduced a matn3 mutation (p.Val189Asp) that resulted in a murine chondrodysplasia characterized by mild short-limbed dwarfism. The equivalent human mutation in MATN3 (p.Val194Asp) has previously been shown to cause an autosomal dominant form of MED in which patients are normal at birth, but develop mild short-limbed dwarfism during childhood (20,49). The final heights of MED patients with MATN3 mutations generally range from the third to seventy-fifth percentile and are therefore often within normal limits (21,49,50). It was therefore not surprising that this mouse model of MED did not have a severe short-limb dwarfism; however, by considering the median bone length measurements in wild-type mice as the fiftieth percentile, a 12% reduction in tibia bone length (seen at day 63 in mice homozygous for the mutation) is below the third percentile (i.e. 4 S.D. below the mean). This observation is therefore consistent with the equivalent human phenotype caused by the p.Val194Asp mutation in which the heights of affected adult males were on the seventy-fifth percentile (49), while an affected child in this family is currently growing at just below the third percentile (Dr Geert Mortier, personal communication).

Although the clinical phenotype in the mouse is only evident from day 14, the histological phenotype is in fact observable from birth. This is characterized by the accumulation of mutant matrilin-3 in the rER, which by day 7 leads to a disruption to chondrocyte morphology and columnar organization within the growth plate. Concurrently, there was an upregulation of BiP and Grp94, which are classical markers for UPR activation (44-46) and by day 21 the UPR and growth plate dysplasia is associated with a reduction in chondrocyte proliferation and spatially dysregulated apoptosis. The differences in the timing of the clinical and histological/molecular manifestations of the murine chondrodysplasia is therefore consistent with the natural history of the human MED phenotype and provides a rationale for the progressive short-limbed dwarfism seen in patients (49). Interestingly, in contrast to the human MED phenotype, which is a dominant disease, both copies of the mutant allele were required for the mice to develop a detectable chondrodysplasia. This might be due, in part, to the different physiology of mice or the inbred nature of the strains that were used to generate this mouse model. Similar discrepancies have been observed in other mice models of human skeletal disease such as achondroplasia (51) and mice that harbour a comp p.Thr585Met mutation (Pirog-Garcia et al., manuscript in preparation) and are suggestive of dominance modification (52,53).

Previous studies to elucidate the structural and functional significance of MATN3 mutations in MED have focused on the use of two different in vitro cell culture systems, namely, primary bovine chondrocytes (28) and a mammalian immortalized cell line (22). In both cases matrilin-3 harbouring MED mutations was retained within the rER of cells and in one system remained associated with ERp72 as an unfolded intermediate (22). Furthermore, electron microscopy of cartilage from an MED patient with a MATN3 mutation showed the presence of dilated cisternae of rER; while IHC analysis confirmed that the retained protein was matrilin-3 (22). However, despite these studies several fundamental questions have remained unresolved. For example, although these in vitro studies have suggested that there is a protein trafficking defect of mutant matrilin-3, neither study was able to demonstrate categorically whether mutant matrilin-3 is present within the cartilage ECM, and if a potentially abnormal ECM is able to provide a suitable environment for chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. IHC analysis of growth plate cartilage from mice homozygous for the mutation demonstrated that while the majority of the mutant protein was retained intracellularly, a smaller proportion was evenly distributed throughout the ECM. Therefore, these data demonstrate for the first time that mutant matrilin-3 can be secreted to some extent from chondrocytes, however, we were unable to determine if this mutant matrilin-3 was present in the ECM as a homo-oligomer (i.e. [matrilin-3]4) or as a hetero-oligomer with matrilin-1 (i.e. [matrilin-1]2 [matrilin-3]2) and it therefore remains a possibility that mutant matrilin-3 monomers can only be secreted when they form hetero-oligomers with normal matrilin-1 monomers.

The morphology of individual chondrocytes, chondrons and indeed the entire growth plate was clearly disrupted in mice that were homozygous for the mutation. The accumulation of protein within dilated cisternae of rER had the effect of altering the shape of some chondrocytes, which were unable to form compact 4- and 8-cell chondrons during cell proliferation. These in turn were unable to align correctly into a columnar arrangement and gave the overall appearance of a disrupted growth plate. It is likely that this misalignment of proliferating cells would have a detrimental affect on linear bone growth. Furthermore, the observed changes in the structure and properties of the ECM are also likely to affect the integrity of the tissue and have a profound affect on cell motility during the proliferation and realignment of chondrocytes at the 2-, 4- and 8-cell stage (54,55). The three-dimensional reconstruction of a 4-cell chondron from both wild-type and mutant mice elegantly illustrates the extent of the accumulation of mutant protein within the distended rER. It is clear from this model that the approximately 9-fold increase in the volume of distended rER is likely to have an adverse physical effect on the chondrocytes, in addition to the UPR. IHC indicated that the accumulation of mutant matrilin-3 was greatest at day 21 (Fig. 3B), but due to technical constraints the three-dimensional reconstructions were only performed on day 7 mice (Fig. 5), therefore the proportion of distended rER would be even greater by day 21.

Prior to this study it was not known whether the retention of mutant matrilin-3 in the rER of chondrocytes would initiate an UPR in vivo. By using a combination of qRT-PCR, western blot analysis and IHC we have been able to establish for the first time that specific chaperone proteins, which are classical markers for UPR activation (44-46), were upregulated in chondrocytes from mutant mice. It is most likely that the activation of the UPR was in direct response to the retention of mutant matrilin-3 and this is normally associated with several downstream consequences, most notable of which is the upregulation of CHOP, a key mediator or rER/cell stress. Interestingly, our observation that mutant matrilin-3 steadily accrues within the rER of chondrocytes suggests that the UPR (including ER-associated degradation) is insufficient to prevent the accumulation of mutant protein. However, we were unable to detect an increase in the relative levels of CHOP expression.

One key goal for generating a murine model of MED was to answer fundamental questions regarding disease mechanisms within the context of the growth plate. Primarily, what is the mechanistic link between the expression of a mutant protein and the decreased linear bone growth and short-limbed dwarfism? The effect of an UPR (and potential rER/cell stress) on chondrocyte proliferation and apoptosis was therefore determined and these data provided novel insight into potential disease mechanisms. We were able to demonstrate for the first time that the relative levels of chondrocyte proliferation were significantly reduced in the growth plate of mice homozygous for the mutation. Interestingly, we did not detect an overall increase in apoptosis; however, apoptosis was spatially dysregulated in the growth plate and significant numbers of TUNEL-positive cells were identified away from the vascular invasion front. These observations suggested that apoptosis was spatially dysregulated rather than increased and are supported by the qRT-PCR data which confirmed that there was no apparent increase in the relative expression of CHOP in mutant chondrocytes. Bearing in mind that chondrocyte proliferation and hypertrophy in the growth plate is vital for long bone growth, any disruption to these processes are likely to severely delay endochondral ossification and eventually lead to short-limb dwarfism. Our data therefore support the hypothesis that reduced chondrocyte proliferation and spatially dysregulated apoptosis is sufficient to cause the progressive short-limb dwarfism that is characteristic of this form of MED.

In summary, therefore we have generated the first relevant murine model of MED and identified mechanistic links between the expression of a mutant gene product and the resulting growth plate dysplasia. Ultimately, this will pave the way for the development of suitable therapeutic approaches for the treatment of diseases within PSACH-MED bone dysplasia family.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of the targeting vector and generation of chimeric mice

A targeting vector was constructed from overlapping lambda clones isolated from a 129/sv library (56). A neo-tk cassette, flanked by loxP sites, was cloned into BamHI/ClaI site of pBluescript II KS (pBSNeotk). The short arm was generated by PCR (SAF 5′-ttctgctcataccgactgg-3′ and SAR 5′-gcaccagctgtaatcatagta-3′) amplification of a 2 kb fragment of mouse genomic DNA, which was digested with Psp OMI/BclI and cloned into the NotI/BamHI sites of the pBSNeotk vector (pBSNeotkSA). The long arm was made from two composite genomic fragments. The 5′ of the long arm, containing the mutation, was generated by PCR amplification of a 1.5 kb fragment from mouse genomic DNA (SalIF 5′-acgcgtcgacttgtttttctgagaggacttcattc-3′ and Mut + XhoIR 5′-cacgggctcgagcagccacctcattcacctggtcctgcggcctcccatctgtatcgataatagctaccttgg-3′). The forward primer had a SalI restriction site (bold), while the reverse contained the XhoI restriction site (bold) found in exon 2, and the mutation which created a ClaI restriction site (italicized). This was digested with SalI and XhoI and cloned into the XhoI site of pBSNeotkSA, disrupting the original XhoI site from the vector and leaving the XhoI site from exon 2 intact. The correct orientation and presence of the mutation was confirmed by digests and sequencing (pBSNeotkSA-SX). Finally, the rest of the long arm, a 7 kb fragment was removed from the genomic clone via XhoI digestion and cloned into the XhoI site of pBSNeotkSA-SX. The orientation was confirmed leaving a continuous 8.5 kb long arm (pBSNeotk-V194D).

The targeting vector DNA (70 μg) was linearized with NotI and used to electroporate 4×107 R1 embryonic stem (ES) cells, grown on feeders and supplemented with leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF), using a Bio-Rad gene pulser set at 0.8 kV and 3 μF for 0.1 ms. Selection with 500 μg/ml G418 began after 24 h for 5-6 days. DNA from clones were digested with SpeI and analysed by Southern blot hybridization using an external probe (Fig. 1B). In order to remove the floxed neo-tk cassette from homologously recombined clones in vitro, ES cells were electroporated as before but with 50 μg of pIC-Cre, a mammalian expression vector containing the Cre transcript. Cultures were selected with FIAU (0.2 μM final concentration) for 6 days. Clones were picked, DNA isolated and detection of only the 12 kb fragment showed removal of the neo-tk cassette. PCR amplification across the neo-tk site confirmed removal of the cassette and presence of the single remaining LoxP site. Targeted ES cells were microinjected into DBA blastocysts to generate chimeric mice. Chimeric males were bred with C57Bl/6 females. Offspring heterozygous for the mutation were used to generate the matn3 p.Val194Asp mouse strain.

Analysis of the skeleton

Skeletal preparations of newborn mice were prepared as described previously (57). Growth curves were produced by measuring body weights of littermates at day 21, 42 and 63. Bone length measurements were taken from X-ray radiographs.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Tissue samples were fixed overnight in ice-cold 10% formalin (histological staining and TUNEL) or 95% ethanol/5% acetic acid (IHC and BrdU). Bone samples were then decalcified in 20% EDTA and embedded in paraffin wax. Antibodies used were anti-matrilin-3 and anti-BrdU (Abcam). IHC was carried out on ethanol/acetic acid-fixed samples. Briefly, endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by a H2O2/methanol wash, followed by hyaluronidase treatment. Samples were blocked with goat serum and BSA in PBS for 1 h, incubated for 1 h with the primary antibody (in PBS/BSA) and then 1 h with the secondary antibody (biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG, Dako Cytomation) in PBS/BSA with goat serum. Slides were then incubated with the ABCcomplex/HRP reagent for 30 min, and developed using DAB. Samples were counterstained with methyl green and mounted with VectaMount. BrdU IHC was performed as above, except that the hyaluronidase step was replaced with an antigen retrieval step (incubated in 4 M HCl for 15 min, then neutralized with 0.1 M borate buffer).

Measurements of in vivo apoptosis was carried out using the DeadEnd™ fluorometric TUNEL system (Promega) and visualized with a Zeiss Axiovision microscope. Nuclei where stained with DAPI while apoptotic cells stained with FITC.

Ultrastructural analysis

Tibia from day 7 mice were fixed overnight in 4% formaldehyde/2.5% gluteraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, followed by three washes in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer. Samples were then incubated (2 h, 4°C) in a secondary fix of 1% osmium tetroxide, followed by three washes in water. En bloc staining of the sample was carried out by incubation (1 h, 4°C) in 0.5% uranyl acetate, followed by water washes. Samples were then dehydrated through an ascending graded acetone series. The acetone was replaced with two changes of propylene oxide, which in turn was replaced with Spurr’s resin. After several changes the resin was polymerized by incubating at 60°C for 48 h. Sections of 70 nm were cut and stained with 0.3% (w/v) lead citrate and images were taken on a FEI Tecnai 12 Biotwin electron microscope and were recorded on 4489 film (Kodak) and scanned using an Imacon Flextight 848 scanner (Precision Camera and Video). Images from EM serial sections were aligned, reconstructed and visualized in IMOD for Linux (58).

qRT-PCR and western blot analysis of mutant chondrocytes

For qRT-PCR rib cages from 3- and 5-day-old mice (wt and m/m) were treated with collagenase for 2 h (Type 1A, 2 mg/ml). The costal cartilage was then dissected from the rib cage and the perichondrium layer removed. The cartilage was then further treated with collagenase for 3 h to digest away the collagen matrix and release the chondrocytes. The chondrocytes were passed through a cell strainer (70 μm) and washed twice with PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended in 500 μl Trizol. Total RNA was then isolated according to manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). cDNA was then generated using random hexamer primers (Superscript III, Invitrogen) and qRT-PCR performed using the SYBR® green PCR method for each chaperone. The following primer sequences were used for BiP (For: 5′-ggcaccttcgatgtgtctcttc-3′ and Rev: 5′-tccatga cccgctgatcaa-3′), Grp94 (For: 5′-taagctgtatgtacg ccgcgt-3′ and Rev: 5′-ggagatcatcggaatccacaac-3′) and 18s RNA (For: 5′-gtaaaccgttgaaccccatt-3′ and Rev: 5′-ccatccaatcggtagcg-3′). For western blot analysis, chondrocytes were isolated as above, but aliquots of 2×105 chondrocytes were prepared and resuspended in 5×SDS loading buffer. These aliquots were run on SDS-PAGE then transferred to nitrocellulase membrane for western blot analysis. Ponceau staining was used to confirm equal loading of total protein isolates. Antibodies to key chaperones associated with the unfolded protein response were used at 1:500 dilutions, namely BiP (Santa Cruz) and Grp94 (Santa Cruz).

Statistical analysis

ANOVA was used to determine differences within and between groups (used for body weight and bone length comparisons), while differences in chondrocyte proliferation, apoptosis and qPCR were analysed using independent t-test. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

The video depicts a three-dimensional reconstruction comparing 4-cell chondrons from wild-type and mutant mice. Cells are colour rendered; nuclei are shown in purple, distended rER in blue and primary cilia in red. The video shows the extent of the accumulation of mutant matrilin-3 within the distended rER.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust (071161/Z/03/Z to MDB) the National Institute of Health (RO1 AR49547-01 to MDB, RBH, KEK and DJT) and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (WA1338/2-4 to RW). This work was undertaken in the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell-Matrix Research and the Histology and Transgenic Mouse core facilities of the Faculty of Life Sciences at the University of Manchester. We would like to thank Dick Heinegard (Lund) for the COMP antibody and Tim Hardingham (Manchester) for the aggrecan antibody.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement. There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shapiro IM, Adams CS, Freeman T, Srinivas V. Fate of the hypertrophic chondrocyte: microenvironmental perspectives on apoptosis and survival in the epiphyseal growth plate. Birth Defects Res. C. Embryo Today. 2005;75:330–339. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornak U, Mundlos S. Genetic disorders of the skeleton: a developmental approach. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:447–474. doi: 10.1086/377110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldring MB, Tsuchimochi K, Ijiri K. The control of chondrogenesis. J. Cell. Biochem. 2006;97:33–44. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zelzer E, Olsen BR. The genetic basis for skeletal diseases. Nature. 2003;423:343–348. doi: 10.1038/nature01659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Working Group on Constitutional Diseases of Bone International nomenclature and classification of the osteochondrodysplasias. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998;79:376–382. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19981012)79:5<376::aid-ajmg9>3.0.co;2-h. 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spranger J. Bone dysplasia ‘families’. Pathol. Immunopathol. Res. 1988;7:76–80. doi: 10.1159/000157098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briggs MD, Chapman KL. Pseudoachondroplasia and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia: mutation review, molecular interactions, and genotype to phenotype correlations. Hum. Mutat. 2002;19:465–478. doi: 10.1002/humu.10066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unger S, Hecht JT. Pseudoachondroplasia and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia: new etiologic developments. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001;106:244–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy J, Jackson G, Ramsden S, Taylor J, Newman W, Wright MJ, Donnai D, Elles R, Briggs MD. COMP mutation screening as an aid for the clinical diagnosis and counselling of patients with a suspected diagnosis of pseudoachondroplasia or multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;13:547–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossi A, Superti-Furga A. Mutations in the diastrophic dysplasia sulfate transporter (DTDST) gene (SLC26A2): 22 novel mutations, mutation review, associated skeletal phenotypes, and diagnostic relevance. Hum. Mutat. 2001;17:159–171. doi: 10.1002/humu.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Segat D, Frie C, Nitsche PD, Klatt AR, Piecha D, Korpos E, Deak F, Wagener R, Paulsson M, Smyth N. Expression of matrilin-1, -2 and -3 in developing mouse limbs and heart. Matrix Biol. 2000;19:649–655. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hedbom E, Antonsson P, Hjerpe A, Aeschlimann D, Paulsson M, Rosa-Pimentel E, Sommarin Y, Wendel M, Oldberg A, Heinegard D. Cartilage matrix proteins. An acidic oligomeric protein (COMP) detected only in cartilage. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:6132–6136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eyre D. Collagen of articular cartilage. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:30–35. doi: 10.1186/ar380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klatt AR, Paulsson M, Wagener R. Expression of matrilins during maturation of mouse skeletal tissues. Matrix Biol. 2002;21:289–296. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(02)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagener R, Ehlen HW, Ko YP, Kobbe B, Mann HH, Sengle G, Paulsson M. The matrilins-adaptor proteins in the extracellular matrix. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3323–3329. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu JJ, Eyre DR. Matrilin-3 forms disulfide-linked oligomers with matrilin-1 in bovine epiphyseal cartilage. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:17433–17438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klatt AR, Nitsche DP, Kobbe B, Morgelin M, Paulsson M, Wagener R. Molecular structure and tissue distribution of matrilin-3, a filament- forming extracellular matrix protein expressed during skeletal development. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:3999–4006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mann HH, Ozbek S, Engel J, Paulsson M, Wagener R. Interactions between the cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and matrilins. Implications for matrix assembly and the pathogenesis of chondrodysplasias. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:25294–25298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budde B, Blumbach K, Ylostalo J, Zaucke F, Ehlen HW, Wagener R, Ala-Kokko L, Paulsson M, Bruckner P, Grassel S. Altered integration of matrilin-3 into cartilage extracellular matrix in the absence of collagen IX. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:10465–10478. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.23.10465-10478.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman KL, Mortier GR, Chapman K, Loughlin J, Grant ME, Briggs MD. Mutations in the region encoding the von Willebrand factor A domain of matrilin-3 are associated with multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:393–396. doi: 10.1038/ng573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson GC, Barker FS, Jakkula E, Czarny-Ratajczak M, Makitie O, Cole WG, Wright MJ, Smithson SF, Suri M, Rogala P, et al. Missense mutations in the beta strands of the single A-domain of matrilin-3 result in multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. J. Med. Genet. 2004;41:52–59. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.011429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotterill SL, Jackson GC, Leighton MP, Wagener R, Makitie O, Cole WG, Briggs MD. Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia mutations in MATN3 cause misfolding of the A-domain and prevent secretion of mutant matrilin-3. Hum. Mutat. 2005;26:557–565. doi: 10.1002/humu.20263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeda K, Nakashima E, Horikoshi T, Mabuchi A, Ikegawa S. Mutation in the von Willebrand factor-A domain is not a prerequisite for the MATN3 mutation in multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2005;136:285–286. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stefansson SE, Jonsson H, Ingvarsson T, Manolescu I, Jonsson HH, Olafsdottir G, Palsdottir E, Stefansdottir G, Sveinbjornsdottir G, Frigge ML, et al. Genomewide scan for hand osteoarthritis: a novel mutation in matrilin-3. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:1448–1459. doi: 10.1086/375556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eliasson GJ, Verbruggen G, Stefansson SE, Ingvarsson T, Jonsson H. Hand radiology characteristics of patients carrying the T(303)M mutation in the gene for matrilin-3. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2006;35:138–142. doi: 10.1080/03009740500303215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Min JL, Meulenbelt I, Riyazi N, Kloppenburg M, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Seymour AB, van Duijn CM, Slagboom PE. Association of matrilin-3 polymorphisms with spinal disc degeneration and with osteoarthritis of the CMC1 joint of the hand. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2006;65:1060–1066. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.045153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loughlin J. The genetic epidemiology of human primary osteoarthritis: current status. Expert. Rev. Mol. Med. 2005;7:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S1462399405009257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otten C, Wagener R, Paulsson M, Zaucke F. Matrilin-3 mutations that cause chondrodysplasias interfere with protein trafficking while a mutation associated with hand osteoarthritis does not. J. Med. Genet. 2005;42:774–779. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.029462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazzarella RA, Srinivasan M, Haugejorden SM, Green M. ERp72, an abundant luminal endoplasmic reticulum protein, contains three copies of the active site sequences of protein disulfide isomerase. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:1094–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maynard JA, Cooper RR, Ponseti IV. A unique rough surfaced endoplasmic reticulum inclusion in pseudoachondroplasia. Lab Invest. 1972;26:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vranka J, Mokashi A, Keene DR, Tufa S, Corson G, Sussman M, Horton WA, Maddox K, Sakai L, Bachinger HP. Selective intracellular retention of extracellular matrix proteins and chaperones associated with pseudoachondroplasia. Matrix Biol. 2001;20:439–450. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hecht JT, Hayes E, Haynes R, Cole WG. COMP mutations, chondrocyte function and cartilage matrix. Matrix Biol. 2005;23:525–533. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hecht JT, Hayes E, Snuggs M, Decker G, Montufar-Solis D, Doege K, Mwalle F, Poole R, Stevens J, Duke PJ. Calreticulin, PDI, Grp94 and BiP chaperone proteins are associated with retained COMP in pseudoachondroplasia chondrocytes. Matrix Biol. 2001;20:251–262. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hecht JT, Makitie O, Hayes E, Haynes R, Susic M, Montufar-Solis D, Duke PJ, Cole WG. Chondrocyte cell death and intracellular distribution of COMP and type IX collagen in the pseudoachondroplasia growth plate. J. Orthop. Res. 2004;22:759–767. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hecht JT, Montufar-Solis D, Decker G, Lawler J, Daniels K, Duke PJ. Retention of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) and cell death in redifferentiated pseudoachondroplasia chondrocytes. Matrix Biol. 1998;17:625–633. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(98)90113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Svensson L, Aszodi A, Heinegard D, Hunziker EB, Reinholt FP, Fassler R, Oldberg A. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein-deficient mice have normal skeletal development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:4366–4371. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4366-4371.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ko Y, Kobbe B, Nicolae C, Miosge N, Paulsson M, Wagener R, Aszodi A. Matrilin-3 is dispensable for mouse skeletal growth and development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:1691–1699. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1691-1699.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aszodi A, Bateman JF, Hirsch E, Baranyi M, Hunziker EB, Hauser N, Bosze Z, Fassler R. Normal skeletal development of mice lacking matrilin 1: redundant function of matrilins in cartilage? Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:7841–7845. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang X, Birk DE, Goetinck PF. Mice lacking matrilin-1 (cartilage matrix protein) have alterations in type II collagen fibrillogenesis and fibril organization. Dev. Dyn. 1999;216:434–441. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199912)216:4/5<434::AID-DVDY11>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mates L, Nicolae C, Morgelin M, Deak F, Kiss I, Aszodi A. Mice lacking the extracellular matrix adaptor protein matrilin-2 develop without obvious abnormalities. Matrix Biol. 2004;23:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Weyden L, Wei L, Luo J, Yang X, Birk DE, Adams DJ, Bradley A, Chen Q. Functional knockout of the matrilin-3 gene causes premature chondrocyte maturation to hypertrophy and increases bone mineral density and osteoarthritis. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:515–527. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zenmyo M, Komiya S, Kawabata R, Sasaguri Y, Inoue A, Morimatsu M. Morphological and biochemical evidence for apoptosis in the terminal hypertrophic chondrocytes of the growth plate. J. Pathol. 1996;180:430–433. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199612)180:4<430::AID-PATH691>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eggli PS, Herrmann W, Hunziker EB, Schenk RK. Matrix compartments in the growth plate of the proximal tibia of rats. Anat. Rec. 1985;211:246–257. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092110304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaufman RJ. Orchestrating the unfolded protein response in health and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:1389–1398. doi: 10.1172/JCI16886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaufman RJ. Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: coordination of gene transcriptional and translational controls. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1211–1233. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kozutsumi Y, Segal M, Normington K, Gething MJ, Sambrook J. The presence of malfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum signals the induction of glucose-regulated proteins. Nature. 1988;332:462–464. doi: 10.1038/332462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zinszner H, Kuroda M, Wang X, Batchvarova N, Lightfoot RT, Remotti H, Stevens JL, Ron D. CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 1998;12:982–995. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chrysis D, Nilsson O, Ritzen EM, Savendahl L. Apoptosis is developmentally regulated in rat growth plate. Endocrine. 2002;18:271–278. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:18:3:271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mortier GR, Chapman K, Leroy JL, Briggs MD. Clinical and radiographic features of multiple epiphyseal dysplasia not linked to the COMP or type IX collagen genes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;9:606–612. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makitie O, Mortier GR, Czarny-Ratajczak M, Wright MJ, Suri M, Rogala P, Freund M, Jackson GC, Jakkula E, Ala-Kokko L, et al. Clinical and radiographic findings in multiple epiphyseal dysplasia caused by MATN3 mutations: description of 12 patients. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2004;125A:278–284. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li C, Chen L, Iwata T, Kitagawa M, Fu XY, Deng CX. A Lys644Glu substitution in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) causes dwarfism in mice by activation of STATs and ink4 cell cycle inhibitors. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:35–44. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dixon J, Dixon MJ. Genetic background has a major effect on the penetrance and severity of craniofacial defects in mice heterozygous for the gene encoding the nucleolar protein Treacle. Dev. Dyn. 2004;229:907–914. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nadeau JH. Modifier genes in mice and humans. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001;2:165–174. doi: 10.1038/35056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aszodi A, Hunziker EB, Brakebusch C, Fassler R. Beta1 integrins regulate chondrocyte rotation, G1 progression, and cytokinesis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2465–2479. doi: 10.1101/gad.277003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grashoff C, Aszodi A, Sakai T, Hunziker EB, Fassler R. Integrin-linked kinase regulates chondrocyte shape and proliferation. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:432–438. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wagener R, Kobbe B, Aszodi A, Liu Z, Beier DR, Paulsson M. Structure and mapping of the mouse matrilin-3 gene (Matn3), a member of a gene family containing a U12-type AT-AC intron. Mamm. Genome. 2000;11:85–90. doi: 10.1007/s003350010018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Braun T, Rudnicki MA, Arnold HH, Jaenisch R. Targeted inactivation of the muscle regulatory gene Myf-5 results in abnormal rib development and perinatal death. Cell. 1992;71:369–382. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90507-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 1996;116:71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.