Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether an association exists between endometriosis and periodontal disease, since endometriosis and periodontal disease are chronic, inflammatory processes more common in those with systemic autoimmune disorders and each disease alters immune modulators.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

University health system and statistical center.

Patients

Data for 4,136 women, ages 18-50, in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1999-2004.

Intervention

None.

Main Outcome Measure

Periodontitis and gingivitis among those with and without self-reported endometriosis.

Results

Multinomial logistic regression showed that women with self-reported endometriosis had significantly (57%) higher odds of having both gingivitis and periodontitis relative to not having periodontal disease, compared to women without self-reported endometriosis (adjusted odds ratio: 1.57; 95% CI: 1.06, 2.33), when controlling for other relevant factors.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest a possible association between endometriosis and periodontal disease. Although it is conceivable that the multifactorial development of endometriosis may be augmented by an immune response to an infectious agent, the potential underlying link between endometriosis and periodontal disease may be a generalized, global immune dysregulation.

Keywords: Endometriosis, periodontal disease, periodontitis, gingivitis, inflammation, autoimmune, NHANES

Introduction

Endometriosis, a potential cause of pelvic pain and infertility, affects 6-10% of reproductive-age women (1) and is characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma located outside the uterine cavity. It is thought that among the multifactorial genesis and persistence of ectopic endometriotic tissue, one contributing factor is a defect in the immune system's ability to clear (2)retrograde menstrual effluent (3). The immunobiology of endometriosis represents a paradigm shift in theories of the pathogenesis of endometriosis (2, 4).

Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory disorder as well. It includes the milder variant gingivitis, which is a reversible inflammation of the soft tissues adjacent to the teeth, and periodontitis, the more severe form of disease, which essentially is the destruction of soft tissues, alveolar bone, and the other supporting structures of the dentition (5). Approximately 50% of U.S. adults have gingivitis, 30% have some degree of periodontitis, and 5-15% have severe periodontal disease (5). Major risk factors include smoking (5), and diabetes (6) with which periodontal disease has a bidirectional relationship (6). As is the case for endometriosis, autoimmunity has been implicated in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease (7).

Since both endometriosis and periodontal disease are chronic, inflammatory processes that are more common in those who have systemic autoimmune disorders and both have been found to alter immune modulators, the aim of this study was to investigate whether or not an association exists between endometriosis and periodontal disease. Investigators have suggested that the relationship between periodontal disease and systemic autoimmune disorders may be that of cause-and-effect, respectively, due to an inflammatory response to seeded periodontal bacterial pathogens. Although a cause-and-effect relationship cannot be ruled out in the case of endometriosis and periodontal disease, we sought to investigate a potential association between the two diseases which could be a sign of a global immune dysregulation.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Data Source

A cross-sectional study was performed using six years of data (1999-2004) from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), administered by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) as a combination of patient interviews and physical examinations designed to assess the health and nutritional status of the U.S. population. In each of three independent two-year NHANES samples (1999-2000, 2001-2002, and 2003-2004), information was collected from nationally representative U.S. samples of persons on a variety of measures. These measures were grouped into four different categories of data sets for each two-year sample: demographics, questionnaire items (e.g., reproductive health, diabetes history), physical examination measurements (e.g., periodontal health), and laboratory measures (e.g., serum cotinine levels). In the present study, only those sampled women having measures collected on each of several variables of research interest from the demographic, examination, laboratory, and questionnaire data files in each two-year sample were included for a secondary analysis. The women having all of these measures collected in each two-year sample were merged into a single data set for analysis.

The merged data set, which included sample records from 1999-2004 for women surveyed on all variables of interest, yielded 4,947 women, and the subpopulation of interest for the study consisted of 4,136 of these women who were ages of 18-50 (a range deemed by the investigators to represent reproductive ages). Because the NHANES was not specifically designed to collect complete data on all of the measures of interest for this particular study (i.e., not all sampled individuals were given a full physical examination, and some individuals did not respond to the questionnaires), and some individuals simply did not have complete data for the analysis variables, multiple imputation (8) was used to analyze the data and assess the robustness of results based on only those sample women with complete data (see Statistical Analysis).

These analyses did not require University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval because the research was secondary analysis of a publicly available dataset. Under federal regulations for human subjects research (45 CFR Part 46), IRB review of analysis of publicly available data sets that are stripped of identifiers is not required.

Sampling Weights

Because individual women had to have a full physical examination to be included in the analysis sample for the present study, sampling weights computed by NCHS staff to reflect 1) unequal probability of selection into the original NHANES sample, 2) subsequent unequal probability of having a physical examination, and 3) other factors, such as survey non-response and adjustment to population controls, were incorporated in the analyses per NHANES documentation (NHANES Analytic Guidelines, Sept. 2006, pgs. 6-7) to ensure that statistical estimates of desired parameters would be nationally representative of the subpopulation of interest (women ages of 18 to 50). The analysis sample for the present study can be considered as a cross-sectional sample of U.S. women from the years 1999 to 2004. Per NHANES guidelines for calculating nationally representative statistical estimates from this six-year time period, the sampling weights provided by NCHS staff for each sample respondent given a physical examination were adjusted so that estimates would represent the six-year time period, rather than two- or four-year time periods (NHANES Analytic Guidelines, Sept. 2006, pg. 12).

Measures

The periodontal health status outcome variable was specified in two ways: healthy vs any periodontal disease (i.e. either gingivitis or periodontitis) and as a 4- category outcome (i.e. healthy, gingivitis only, periodontitis only, or gingivitis and periodontitis). The data to define the periodontal health status outcome were derived from clinical oral health examination data collected for probing pocket depths, gingival bleeding, and clinical attachment levels, based on random half-mouth evaluations. The data from the 1999-2000 NHANES included probing assessments for pocket depths and attachment level at 2 sites per tooth and a quadrant-level gingival bleeding indicator for gingivitis. For the 2001-2004 NHANES data, three sites per tooth were assessed for probing pocket depth and attachment level, and each tooth was individually evaluated for gingival bleeding. An outcome of ‘gingivitis only’ was defined as 1 or more quadrants or 1 or more sites with gingival bleeding and no periodontitis. An outcome of ‘periodontitis’ was defined as 1 or more teeth with 1 or more sites having probing pocket depth of 4 mm or greater and attachment loss greater than or equal to 2 mm (8). Individuals with neither gingivitis nor periodontitis were considered to have healthy periodontal status.

The principal exposure variable, indicating history of endometriosis, was derived from the interview response to the question of whether the woman was told by a physician that she had endometriosis. There were no additional indicators for a history of endometriosis in the NHANES database. Additional explanatory variables evaluated in this study included established risk factors or indicators for periodontal disease and variables considered to confound or modify the effect of endometriosis. The risk factors/indicators associated with periodontal disease included age (18-29, 30-30, 40+), race/ethnicity (Mexican-American, other Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and other racial/ethnic groups), education (less than high school, high school diploma, or education beyond high school diploma), household income ($0-19,999, $20,000-$44,999, $45,000-74,999, $75,000+), smoking status based on serum cotinine (>15 ng/mL) (9, 10), and diabetes (defined as either a self-reported history of diabetes diagnosis by a physician or other health provider, taking insulin or oral hypoglycemic agent, or having fasting plasma glucose of 126 mg/dL or greater; cases classified as ‘borderline’ in the NHANES data were set to missing). Other covariates associated with endometriosis included age at first period (in years: 8-11, 12, 13, or 14 or more), parity (0, 1, 2, 3 or more), current pregnancy status (pregnant or not pregnant determined by self-report on the reproductive health questionnaire in conjunction with a serum human chorionic gonadotropin assay).

Statistical Analysis

Complete-Case Analyses

Initial analyses performed on the 4,136 women in the analysis subpopulation were conducted by excluding respondents with missing data on any of the analysis variables. Weighted statistical estimates of the percentage of respondents in the subpopulation of women having certain values on the analysis variables were initially computed to provide a descriptive summary of the subpopulation of interest represented by the analysis subsample. Binary logistic and multinomial logistic regression analyses were then performed considering only those cases with complete data on all measures, to estimate the relationships of endometriosis with the binary periodontal health status outcome (no gingivitis or periodontitis vs. gingivitis or periodontitis) and the four-category dental health outcome, while controlling for the relationships of other relevant predictors with the periodontal status outcomes. Due to the exploratory nature of this analysis, a backward selection technique was used when fitting the regression models, to determine the subsets of predictors having significant associations with each outcome. In each analysis, Taylor Series Linearization was used to compute standard errors for the statistical estimates incorporating the stratified and clustered design features of the NHANES samples and providing information about the sampling error associated with the estimates. Because the 4,136 women represent a sample from the subpopulation of women between the ages of 18 and 50, methods appropriate for subpopulation analyses (11) were applied to ensure that the full complex designs of the NHANES samples were taken into account for calculation of robust standard errors. All complete-case analyses were performed using procedures in the SAS (Version 9.1.3) and SUDAAN (Version 9.0.1) software packages designed for the analysis of complex sample survey data.

Multiple Imputation Analyses

Because the analysis sample for the multivariate analyses (e.g., binary logistic regression) was reduced by roughly 50% due to the presence of missing data on the individual analysis variables (the variable with the highest amount of missing data was parity, with 1,206 of the 4,136 women having missing data), multiple imputation analysis was used to examine whether results based on the complete-case analyses remained stable after imputation of missing values, and to allow for more statistical power to detect relationships of interest between the analysis variables. The sequential regression imputation method (SRIM) was used in the IVEware software package (12) to generate five complete data sets with all missing values imputed (with n = 4,947 having complete data), and the same analyses described above for the complete cases were once again performed on each of the five imputed data sets. The results from the five sets of analyses were then combined per methodology described by Little and Rubin (13) to generate a final overall set of multiple imputation estimates for each analysis, reflecting both within- and between-imputation variance in the statistical estimates. The overall MI estimates were compared with the complete-case estimates to determine whether the results changed in a substantively after multiple imputations of the missing data.

Results

The results in Table 1 indicate that the subpopulation of women, aside from being ages 18-50 years, is estimated to be 66% white, 59% well-educated (more than a high school degree), well-represented in each of the income categories, more than 50% married, and 50% healthy in terms of periodontal health status; more than 90% have never had endometriosis, 73% have a low cotinine level, only 8% have never had a child, and 94% are not currently pregnant. In addition, the prevalence of diabetes is under 3%. We also note that the process of multiple imputation did not change the subpopulation estimates substantially, and provided complete data sets for the multivariable analyses.

Table 1.

Weighted estimates of frequency distributions for the analysis variables, for the subpopulation of interest (before and after multiple imputations of item-missing values).

| Analysis Variable | n (pre-imputation) | Weighted % (SE) | n (post-imputation)a | Weighted % (SE)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Mexican-American | 1022 | 8.66% (0.95) | 1022 | 8.66% (0.95) |

| Hispanic | 223 | 6.84% (1.31) | 223 | 6.84% (1.31) |

| White | 1836 | 66.06% (1.91) | 1836 | 66.06% (1.91) |

| Black | 882 | 13.30% (1.19) | 882 | 13.30% (1.19) |

| Other | 173 | 5.14% (0.63) | 173 | 5.14% (0.69) |

| Education | ||||

| Less than HS | 1067 | 16.97% (0.81) | 1068 | 16.98% (0.81) |

| HS Diploma | 961 | 24.21% (1.04) | 962 | 24.23% (1.04) |

| More than HS | 2104 | 58.81% (1.38) | 2106 | 58.80% (1.38) |

| Income | ||||

| $0 – $19,999 | 827 | 18.23% (0.88) | 847 | 17.26% (0.85) |

| $20,000+ | 2922 | 81.77% (0.88) | 3289 | 82.75% (0.85) |

| $20,000 – $44,999 | 1183 | 29.22% (1.36) | 1319 | 29.33% (1.35) |

| $45,000 – $74,999 | 836 | 23.70% (0.90) | 915 | 23.49% (0.87) |

| $75,000+ | 903 | 28.84% (1.53) | 1055 | 29.92% (1.51) |

| Periodontal Health Status | ||||

| Healthy | 1466 | 49.85% (2.56) | 1824 | 49.33% (2.31) |

| Any Periodontal Disease | 1865 | 50.15% (2.56) | 2312 | 50.67% (2.31) |

| Gingivitis Only | 1154 | 31.32% (1.68) | 1412 | 31.16% (1.54) |

| Periodontitis Only | 168 | 5.58% (0.60) | 230 | 5.94% (0.68) |

| Gingivitis and Periondontitis | 543 | 13.25% (1.42) | 670 | 13.57% (1.32) |

| Ever Had Endometriosis? | ||||

| Yes | 235 | 8.67% (0.71) | 263 | 8.61% (0.73) |

| No | 3442 | 91.33% (0.71) | 3873 | 91.39% (0.73) |

| High Cotinine (> 15 ng/mL) | ||||

| Yes | 869 | 26.60% (1.14) | 946 | 26.75% (1.15) |

| No | 2955 | 73.40% (1.14) | 3190 | 73.25% (1.15) |

| Age at First Period | ||||

| 8-11 | 834 | 22.26% (0.82) | 944 | 22.16% (0.81) |

| 12 or Higher | 2774 | 77.74% (0.82) | 3192 | 77.84% (0.81) |

| 12 | 969 | 26.81% (1.02) | 1114 | 26.85% (0.96) |

| 13 | 901 | 26.54% (0.93) | 1048 | 26.70% (0.88) |

| 14+ | 904 | 24.39% (0.69) | 1030 | 24.29% (0.69) |

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | 195 | 7.62% (0.80) | 263 | 7.14% (0.91) |

| 1 or More | 2735 | 92.38% (0.80) | 3873 | 92.86% (0.91) |

| 1 | 779 | 24.64% (1.07) | 1130 | 25.39% (1.15) |

| 2 | 931 | 35.64% (1.18) | 1427 | 38.30% (1.16) |

| 3+ | 1025 | 32.10% (1.15) | 1317 | 29.18% (1.17) |

| Pregnancy | ||||

| Currently Pregnant | 765 | 6.04% (0.37) | 778 | 6.29% (0.40) |

| Not Pregnant | 3294 | 93.96% (0.37) | 3358 | 93.71% (0.40) |

| Diabetes Statusc | ||||

| Yes | 150 | 2.96% (0.29) | 152 | 2.99% (0.30) |

| No | 3957 | 97.04% (0.29) | 3984 | 97.01% (0.30) |

n = 4136 in the case of each variable.

Based on the results of a multiple imputation analysis with M = 5 imputed data sets.

Cases coded as “Borderline” are set to missing, and eligible for imputation.

Results from fitting the binary logistic regression model to the outcome broadly measuring periodontal health status (any periodontal disease vs. healthy) are presented in Table 2, before and after multiple imputations of the missing data. In the complete-case analyses, the following predictors were not found to have a significant relationship with periodontal disease in design-based Wald tests, and were dropped from the model: diabetes, age at first period, high serum cotinine, age, and the parity indicator. After dropping these predictors, all other covariates with the exception of endometriosis (education, ethnicity, income, and pregnancy) had a statistically significant (p < 0.05) association with the outcome in the complete case analysis. Due to missing data, only 2,052 observations (out of 4,136) were used to fit the initial model in the complete case analysis, and only 2,804 observations were used to fit the subsequent reduced model. The same reduced model was fitted when performing the multiple imputation analyses, and endometriosis was found to have a marginally significant association with the binary outcome.

Table 2.

Weighted Estimates of Adjusted Odds Ratios (AORs) and design-based 95% confidence intervals (CIs), indicating the association of endometriosis with the binary periodontal health status outcome (before and after multiple imputations), in addition to all other statistically significant associations.

| Predictor | Complete-Case Analysisa AOR (95% CI) | Multiple Imputation Analysisb AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Endometriosis | ||

| Yes | 1.20 (0.84, 1.72) | 1.31 (0.91, 1.88) |

| No | REFc | REF |

| Education | ||

| Less than HS | 1.56 (1.09, 2.24) | 1.56 (1.16, 2.11) |

| HS Diploma | 1.54 (1.23, 1.92) | 1.46 (1.22, 1.74) |

| More than HS | REF | REF |

| Race / Ethnicity | ||

| Mexican- American | 1.84 (1.27, 2.67) | 1.76 (1.33, 2.34) |

| Hispanic | 1.33 (0.87, 2.04) | 1.52 (1.08, 2.14) |

| White | REF | REF |

| Black | 1.56 (1.14, 2.12) | 1.49 (1.16, 1.93) |

| Other | 1.75 (1.07, 2.87) | 1.66 (1.18, 2.33) |

| Income | ||

| $0 – $19,999 | REF | REF |

| $20,000+ | 0.66 (0.50, 0.87) | 0.71 (0.55, 0.93) |

| Pregnancy Status | ||

| Currently Pregnant | 1.40 (1.01, 1.93) | 1.50 (1.14, 1.99) |

| Not Pregnant | REF | REF |

Subpopulation n = 2,804

Subpopulation n = 4,136; M = 5 Imputations

REF = Reference Category

The results of the multivariable analyses presented in Table 2 indicate that in general, white women in this subpopulation have the lowest odds of having poorer periodontal health (for example, Mexican-American women are estimated to have between 76% (multiple imputation analysis) and 84% (complete-case analysis) higher odds of having any periodontal disease compared to white women). In addition, higher income and higher education result in lower odds of having a poor outcome, while being pregnant increases the odds of having a poor outcome by roughly 40 to 50%. We note that endometriosis has a marginally significant association with the odds of having a poor outcome based on the multiple imputation analysis, where women who have been told that they have endometriosis have 31% higher odds of having a poor outcome (AOR = 1.31, 95% CI = 0.91, 1.88).

Table 3 presents results from fitting the multinomial logistic regression model to the outcome measuring the four specific categories of dental health in the complete case analysis. Wald tests of the independent predictors in the complete case analysis revealed that the following predictors should be dropped from the model, due to lack of significance (p < 0.10): age at first period, diabetes, and the parity indicator. The design-based Wald test for the endometriosis indicator in the reduced model indicated that endometriosis had a statistically significant association with the four-category outcome (Wald test p = 0.0189) when controlling for the relationships of the other significant predictors with the outcome in the complete case analysis. Specifically, the results showed that women with endometriosis had significantly (57%) higher odds of having gingivitis and periodontitis relative to not having periodontal disease, compared to women without endometriosis (AOR: 1.57; 95% CI: 1.06, 2.33). Due to missing data, only 2,052 observations (out of 4,136) were used to fit the initial model, and only 2,664 observations were used to fit the reduced model.

Table 3.

Weighted Estimates of Adjusted Odds Ratios (AORs) and design-based 95% confidence intervals (CIs), indicating the association of endometriosis with the four-category periodontal health status outcome (in the complete case analysis, before multiple imputations), in addition to all other statistically significant associations.

| Gingivitis Only | Periodontitis Only | Gingivitis and Periodontitis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | AOR, 95% CI | AOR, 95% CI | AOR, 95% CI |

| Endometriosisb | |||

| Yes | 1.26 (0.83, 1.91) | 0.42 (0.13, 1.34) | 1.57 (1.06, 2.33) |

| No | REF | REF | REF |

| Educationc | |||

| Less than HS | 1.28 (0.83, 1.97) | 2.57 (1.61, 4.11) | 1.62 (0.95, 2.74) |

| HS Diploma | 1.33 (1.04, 1.70) | 1.92 (1.13, 3.26) | 1.65 (1.03, 2.66) |

| More than HS | REF | REF | REF |

| Age Groupc | |||

| 18-29 | 1.58 (1.16, 2.17) | 0.73 (0.41, 1.30) | 0.62 (0.38, 1.02) |

| 30-39 | 1.40 (1.08, 1.82) | 0.84 (0.45, 1.54) | 0.75 (0.51, 1.11) |

| 40+ | REF | REF | REF |

| Race / Ethnicityc | |||

| Mexican-American | 1.77 (1.23, 2.55) | 1.03 (0.56, 1.88) | 2.76 (1.57, 4.86) |

| Hispanic | 1.28 (0.84, 1.96) | 1.04 (0.38, 2.87) | 1.47 (0.64, 3.34) |

| White | REF | REF | REF |

| Black | 1.19 (0.81, 1.73) | 1.06 (0.63, 1.80) | 2.78 (1.79, 4.31) |

| Other | 1.86 (1.09, 3.15) | 1.68 (0.58, 4.84) | 1.74 (0.74, 4.11) |

| Incomec | |||

| $0 – $19,999 | REF | REF | REF |

| $20,000+ | 0.70 (0.48, 1.01) | 0.65 (0.36, 1.17) | 0.58 (0.42, 0.79) |

| Cotininec | |||

| < 15 ngmL | REF | REF | REF |

| >= 15 ngmL | 0.86 (0.63, 1.18) | 1.45 (0.92, 2.28) | 1.44 (0.95, 2.17) |

| Pregnancy Statusa | |||

| Currently Pregnant | 1.19 (0.83, 1.69) | 1.35 (0.72, 2.50) | 1.77 (1.09, 2.89) |

| Not Pregnant | REF | REF | REF |

Baseline Outcome Category = Healthy

Subpopulation n = 2,664 (complete data); REF = Reference Category

p < 0.10 based on design-adjusted Wald test

p < 0.05 based on design-adjusted Wald test

p < 0.01 based on design-adjusted Wald test

The results from the multivariable analysis presented in Table 3 suggest other meaningful associations based on the cases with complete data. In general, lower education levels increase the risk of having adverse outcomes; younger women have a higher odds of having gingivitis only relative to being healthy; white women again have a reduced odds of having adverse outcomes; higher income tends to result in a lower odds of having adverse outcomes; higher cotinine levels tend to increase the odds of having adverse outcomes; and currently being pregnant tends to increase the odds of having adverse outcomes as well.

The results based on the analysis of the complete data set (throwing out cases with missing data) were essentially replicated in the multiple imputation analyses, suggesting that the findings are robust. Specifically, the risk of having both adverse outcomes relative to being healthy was found to be increased by 44% after controlling for the relationships of the other predictors in Table 3 with the four-category outcome (RRR = 1.44, 95% CI = 0.92, 2.25). Even after using a statistically valid technique to impute the missing values (14), we have essentially the same findings, only using a complete data set rather than one with 50% of the cases lost due to missing data. This suggests the findings would remain stable in an even larger sample.

Discussion

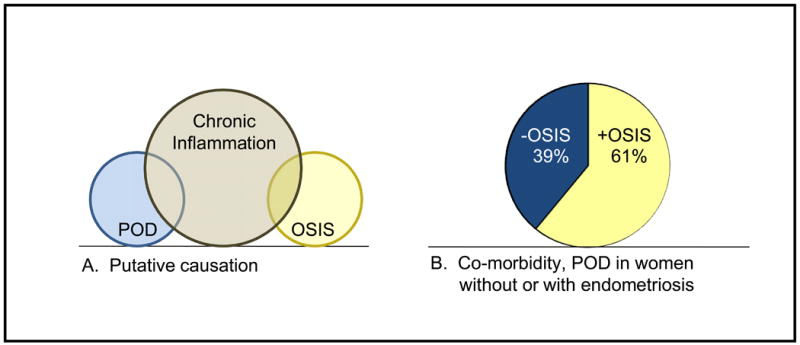

The results of this study provide evidence of a statistically meaningful association between endometriosis and periodontal disease, after adjusting for other relevant predictors of periodontal disease. Specifically, the odds of having both gingivitis and periodontitis relative to being healthy were increased by 57% if a woman had been told that she had endometriosis, when controlling for the relationships of the other predictors with the periodontal health status outcome. That is to say amongst a population of 100 women suffering from gingivitis and periodontitis, 61 will have the additional disease burden of endometriosis while the remaining 39 will not (Figure, Part B).

Figure.

Part A, putative causation Venn diagram illustrating the concept of baseline chronic inflammation causing periodontal disease (or vice-versa) as well as endometriosis (or vice-versa). Part B, pie chart showing the main finding from this NHANES study, namely a greater incidence of periodontal disease among those with self-reported endometriosis (61%) when compared to those without self-reported endometriosis (39%). POD: periodontal disease, Osis: endometriosis.

Although endometriosis and periodontal disease affect different systems and traditionally have appeared to be unrelated, each disease process is characterized as a chronic, inflammatory disorder that is associated with an altered immune response (Figure, Part A). This, so-called “global immune dysregulation” could account for the increased incidence other systemic, autoimmune disorders for each ailment. For example, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis as well as other autoimmune inflammatory conditions, hypothyroidism, allergies, fibromyalgia, asthma and multiple sclerosis are more common in women with endometriosis (15, 16). In parallel, associations have been found between periodontal disease and systemic disorders such as diabetes mellitus (8, 17), cardiovascular disease (18-20), pulmonary disease (21-23), and preterm delivery (22, 24-29).

Furthermore, endometriosis and periodontal disease have each been shown to be associated with altered levels of immune modulators. Specifically, the presence of endometriotic lesions has been associated with decreased Natural Killer (NK) Cell activity and cytotoxicity against endometrial cells (2, 30, 31), as well as increased levels of sICAM-1, peripheral monocytes, peritoneal macrophages, and lymphocytes. In addition, increased levels of cytokines and factors such as IL (interleukin)-1beta, IL-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, vascular endothelial growth factor, RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 have been demonstrated in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis (32-39) Chronic periodontitis is linked to a chronic systemic inflammatory burden secondary to the systemic dissemination of periodontal pathogenic bacteria, their products (e.g. lipopolysaccharides), and locally-produced inflammatory mediators (i.e., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, prostaglandin E2, and thromboxane B2) (40-42).

As with most population-based surveys, NHANES was not specifically designed to address the topic of this study and missing data is a potential limitation. Use of multiple imputation procedures in the analyses tempered this limitation. The results support the value of future focused investigations on this topic with data collection directed towards eliminating missing data on the specific variables of interest in assessing the suggested relationships identified. In addition, NHANES measures used to define the presence and/or degree of this study's diseases of interest inherently pose limitations. Examples include the relative inaccuracy of the self-reporting of endometriosis as compared to data indicating laparoscopic findings and the differences in the literature in regards to variables used to create periodontal disease indicators. Another limitation of NHANES is that the dental examination data were derived from random half-mouth examinations, measuring two or three sites per tooth rather than the six sites used in full-mouth periodontal examinations. The NHANES periodontal examination procedure is recognized to underestimate the prevalence of periodontal disease (43, 44). This underestimation would lead to non-differential misclassification among those with and without endometriosis, attenuating the strength of the association identified in the analysis and therefore suggesting that the associations identified in this study may be even stronger than reported here.

Although it is not out of the question that the multifactorial development of endometriosis may be augmented by an immune response to an infectious agent, the potential underlying link between the two diseases may be a generalized, global immune dysregulation.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Supported by: NIH 5K23HD043952-02 (DIL), NIH T32 HD070048 (SK)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None (for all four authors).

Capsule: In this cross-sectional study, women with self-reported endometriosis had higher odds of having both gingivitis and periodontitis relative to not having periodontal disease, when compared with women without self-reported endometriosis.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364:1789–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lebovic DI, Mueller MD, Taylor RN. Immunobiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01630-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sampson JA. Peritoneal endometriosis due to menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1927;14:422–9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nothnick WB. Treating endometriosis as an autoimmune disease. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:223–31. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01878-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burt B. Position paper: epidemiology of periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1406–19. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.8.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor GW. Bidirectional interrelationships between diabetes and periodontal diseases: an epidemiologic perspective. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:99–112. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma CG, Pradeep AR. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies: a renewed paradigm in periodontal disease pathogenesis? J Periodontol. 2006;77:1304–13. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novak KF, Taylor GW, Dawson DR, Ferguson JE, 2nd, Novak MJ. Periodontitis and gestational diabetes mellitus: exploring the link in NHANES III. J Public Health Dent. 2006;66:163–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2006.tb02574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pirkle JL, Flegal KM, Bernert JT, Brody DJ, Etzel RA, Maurer KR. Exposure of the US population to environmental tobacco smoke: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988 to 1991. JAMA. 1996;275:1233–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernert JT, Jr, Turner WE, Pirkle JL, Sosnoff CS, Akins JR, Waldrep MK, et al. Development and validation of sensitive method for determination of serum cotinine in smokers and nonsmokers by liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 1997;43:2281–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochran W. Sampling techniques. 3rd. New York: Wiley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raghunathan TE, S P, Van Hoewyk J. IVEware: imputation and variance estimation software. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Causal effects in clinical and epidemiological studies via potential outcomes: concepts and analytical approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:121–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raghunathan TE, L J, VanHoewyk, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Survey Methodology. 2001;27:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinaii N, C SD, Ballweg ML, Nieman LK, Stratton P. Autoimmune and related diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:S7–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alviggi C, Carrieri PB, Pivonello R, Scarano V, Pezzella M, De Placido G, et al. Association of pelvic endometriosis with alopecia universalis, autoimmune thyroiditis and multiple sclerosis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006;29:182–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03344095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mealey BL, Oates TW. Diabetes Mellitus and Periodontal Diseases. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1289–303. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonetti MS, D'Aiuto F, Nibali L, Donald A, Storry C, Parkar M, et al. Treatment of periodontitis and endothelial function. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:911–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demmer RT, Desvarieux M. Periodontal infections and cardiovascular disease: the heart of the matter. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(Suppl):14S–20S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0402. quiz 38S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck JD, Offenbacher S. Systemic effects of periodontitis: epidemiology of periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2089–100. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scannapieco FA, Ho AW. Potential associations between chronic respiratory disease and periodontal disease: analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. J Periodontol. 2001;72:50–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teng YT, Taylor GW, Scannapieco F, Kinane DF, Curtis M, Beck JD, et al. Periodontal health and systemic disorders. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:188–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azarpazhooh A, Leake JL. Systematic review of the association between respiratory diseases and oral health. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1465–82. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Offenbacher S, Katz V, Fertik G, Collins J, Boyd D, Maynor G, et al. Periodontal infection as a possible risk factor for preterm low birth weight. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1103–13. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeffcoat MK, Hauth JC, Geurs NC, Reddy MS, Cliver SP, Hodgkins PM, et al. Periodontal disease and preterm birth: results of a pilot intervention study. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1214–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeffcoat MK, Geurs NC, Reddy MS, Cliver SP, Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC. Periodontal infection and preterm birth: results of a prospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:875–80. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goepfert AR, Jeffcoat MK, Andrews WW, Faye-Petersen O, Cliver SP, Goldenberg RL, et al. Periodontal disease and upper genital tract inflammation in early spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:777–83. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000139836.47777.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF. Preterm birth and periodontal disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1925–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe068210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiong X, Buekens P, Fraser WD, Beck J, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review. Bjog. 2006;113:135–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oosterlynck DJ, Cornillie FJ, Waer M, Vandeputte M, Koninckx PR. Women with endometriosis show a defect in natural killer activity resulting in a decreased cytotoxicity to autologous endometrium. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:45–51. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson TJ, Hertzog PJ, Angus D, Munnery L, Wood EC, Kola I. Decreased natural killer cell activity in endometriosis patients: relationship to disease pathogenesis. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:1086–8. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammond MG, Oh ST, Anners J, Surrey ES, Halme J. The effect of growth factors on the proliferation of human endometrial stromal cells in culture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:1131–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90356-n. discussion 6-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan IP, Tseng JF, Schriock ED, Khorram O, Landers DV, Taylor RN. Interleukin-8 concentrations are elevated in peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:929–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lebovic DI, Bentzien F, Chao VA, Garrett EN, Meng YG, Taylor RN. Induction of an angiogenic phenotype in endometriotic stromal cell cultures by interleukin-1b. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:269–75. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iwabe T, Harada T, Sakamoto Y, Iba Y, Horie S, Mitsunari M, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment reduced serum interleukin-6 concentrations in patients with ovarian endometriomas. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:300–4. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00609-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wieser F, Fabjani G, Tempfer C, Schneeberger C, Sator M, Huber J, et al. Analysis of an interleukin-6 gene promoter polymorphism in women with endometriosis by pyrosequencing. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2003;10:32–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu MY, Ho HN. The role of cytokines in endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2003;49:285–96. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0897.2003.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dmowski WP, Gebel HM, Rawlins RG. Immunologic aspects of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1989;16:93–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang WC, Chen HW, Au HK, Chang CW, Huang CT, Yen YH, et al. Serum and endometrial markers. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18:305–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Offenbacher S, Beck JD. A perspective on the potential cardioprotective benefits of periodontal therapy. Am Heart J. 2005;149:950–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loos BG. Systemic markers of inflammation in periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2106–15. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D'Aiuto F, Graziani F, Tete S, Gabriele M, Tonetti MS. Periodontitis: from local infection to systemic diseases. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2005;18:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beck JD, Caplan DJ, Preisser JS, Moss K. Reducing the bias of probing depth and attachment level estimates using random partial-mouth recording. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kingman A, Morrison E, Loe H, Smith J. Systematic errors in estimating prevalence and severity of periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1988;59:707–13. doi: 10.1902/jop.1988.59.11.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]