Abstract

Since the first histone lysine demethylase KDM1 (LSD1) was discovered in 2004, a great number of histone demethylases have been recognized and shown to play important roles in gene expression, as well as cellular differentiation and animal development. The chemical mechanisms and substrate specificities have already been extensively discussed elsewhere. This review focuses primarily on regulatory mechanisms that modulate demethylase recruitment and activity.

Introduction

In eukaryotes, epigenetic modifications refer to heritable alterations that affect chromatin environment and gene expression without changing DNA sequence, so that an identical genome can be interpreted differently in a temporal and spatial-dependent manner. DNA methylation and possibly histone post-translational modifications are the two major means by which epigenetic regulation occurs. Numerous modifications have been identified on histones, such as methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquination. Among these, histone lysine methylation has been linked to DNA methylation, and is therefore strongly implicated in epigenetic regulation. Methylation takes place on the side chains of both lysine (K) and arginine (R) residues. A total of 6 major lysine residues (H3K4, H3K9, H3K27, H3K36, H3K79 and H4K20) have been shown to be mono-, di- and tri-methylated. Unlike histone lysine acetylation, which is generally coupled to activation, both the position of the lysine residue and the degree of methylation can have different biological associations. Patterns of specific lysine methyl modifications are achieved by a precise lysine methylation system, consisting of proteins that add, remove and recognize the (reviewed in[1]) specific lysine methyl marks. The majority of these enzymes show significant substrate specificity, underscoring the complexity of lysine methylation in epigenetic regulation. The recent discovery of histone lysine demethylases[2,3] indicated that the maintenance of histone methylation balance requires the action of both methylases and demethylases. Based on the emerging findings from the recent demethylase studies, we suggest that modulation of demethylase activity involves regulation at multiple levels, including gene expression, recruitment, coordination with other epigenetic marks, and post translational modifications (PTMs) (Figure 1).

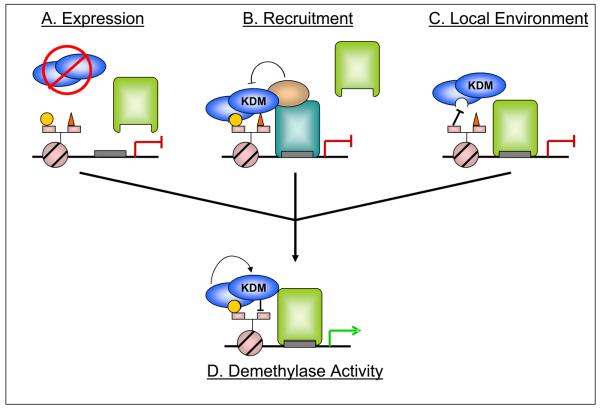

Figure 1. Model for demethylase regulation by expression, interacting proteins and local chromatin environment.

Multiple levels of regulation must coordinate to allow appropriate demethylase activity – the histone lysine demethylase (KDM - blue ovals) must be expressed, the appropriate DNA binding factor and cofactors must be present and associated, and the local chromatin environment must allow (or actively promote) complex stability. A) Regulation of the demethylase expression provides the first, most general level of regulation. B) Protein:protein interactions allow for construction of complexes with various compositions, as directed by different DNA-binding modules (blue and green rectangles indicate different DNA binding factors). In this example, KDM association via the bound transcription factor (blue rectangle) does not lead to enzymatic activity due to suppression by an associated cofactor, despite the permissive local environment. C) Local chromatin environment affects demethylase activity by recruiting and/or stabilizing the appropriate complex. Here, despite the proper complex formation, the absence of a particular modification (yellow circle) leads to dissociation of the complex. D) All these conditions, signaled by differentiation or external stimuli, coordinately regulate KDM activity (leading to loss of red triangle, representing a repressive methylation mark) and a change in transcriptional status (gene is now actively transcribed). Although a gene activating event is pictured, this model holds true for demethylases that act to repress transcription as well.

Regulation of demethylase expression

Demonstration of histone demethylase activity in vitro suggests that simple association between enzyme and substrate is sufficient for demethylation reaction, raising the possibility that regulatory mechanisms may exist in vivo to modulate and prevent inappropriate demethylation. One method of regulation is at the level of demethylase gene expression. Indeed, many demethylases show restricted patterns of embryonic and adult expression (see Table 1), as well as in response to environmental stimuli.

Table 1. Demethylase developmental expression patterns and mutant/knockdown phenotype as reported for mammal, fly and worm.

Light gray boxes contain reported developmental expression patterns, dark gray boxes contain adult/tissue-specific expression patterns, and white boxes contain mutant/knock-down phenotypes. Fly and worm homolog names are in parentheses after gene abbreviation (in bold) - 1B(CG11033) represents the fly homolog of JHDM1B, for example. All non-referenced data was consolidated from the following sources: mouse adult expression – NCBI:MPSS large scale transcriptome analysis of C57BL/6J (GDS868) – tissues above 50th percentile; fly developmental expression – NCBI:fly development time course microarray (GDS191) – phases above 50th percentile; fly adult expression – FlyAtlas:notated as up-regulated on tissue microarray; fly phenotype – as noted in FlyBase; worm developmental expression – as noted in WormBase, or stage-specific from Kohara NextDB; worm adult expression – as noted in WormBase, or stage-specific from Kohara NextDB; worm phenotype – as noted in WormBase. (NR – none reported; NH – no homolog IDed through NCBI HomoloGene)

| Family | Human Genes |

Substrate | Mouse (M. musculus) | Fly (D. melanogaster) | Worm (C. elegans) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSD1 (KDM1) |

LSD1 | H3K4me2/1; H3K9me2/1 |

NR | (CG17149): early embryonic | (spr-5; T08D10.2): early embryonic, developing germline |

| pituitary[23]; brain; thymus; testis; ESCs |

ovary | germline | |||

| embryonic lethal (E7.5)[23] | female sterility | SPR-5: NR T08D10.2: extended lifespan[49] |

|||

| JHDM1 (KDM2) |

JHDM1A JHDM1B |

H3K36me2; H3K4me3 |

NR |

1A: NH 1B (CG11033): up-reg in mid-late embryo and metamorph, down- reg in larva |

1A: NH 1B (T26A5.5b): intestine, developing vulva, head/tail neurons |

|

1A: adrenal; brain; eye; thyroid; uterus 1B: uterus; ESCs; oocytes[8] |

brain; ovary; thoracicoabdominal ganglion |

intestine | |||

| NR | NR | slow growth; increased mutations[50] |

|||

| JHDM2 (KDM3) |

JMJD1A JMJD1B JMJD1C |

H3K9me2 |

1A: undifferentiated cells[51] 1B: NR 1C: undifferentiated cells[52] |

1A;1C: NH 1B (CG8165): NR |

NH |

|

1A: adrenal; skin; spinal cord; thymus; thyroid; cervix; testis[53]; bladder; ESCs 1B: pituitary 1C: brain; thymus; ESCs |

1B: brain, tubule, hindgut, thoracicoabdominal ganglion |

||||

|

1A: spermatogenesis defect[11] 1B;1C: NR |

1B: viable; fertile | ||||

| JMJD2 (KDM4) |

JMJD2A JMJD2B JMJD2C JMJD2D |

H3K9me3/2; H3K36me3/2 |

A: early embryonic[54] B: early embryonic[54] C: preferentially in undifferentiated cells[54] D: NR |

A;D (CG15835): early embryonic B: NH C (CG33182): NR |

(jmjd-2): weak in very early embryo |

|

A: heart, brain, thymus, ovary[55] B: testis, hematopoietic system[8] C: eye; ESCs; immunocytes[8] D: NR |

A;D: ovary; testis C: brain; thoracicoabdominal ganglion; testis |

constitutive; stronger in pharynx | |||

| NR |

A;D: NR C: viable; fertile |

increased germ cell apoptosis[33] | |||

| JARID (KDM5) |

JARID1A JARID1B JARID1C JARID1D JARID2 (not active) |

K4me3/2 |

1A: NR 1B: epiblast; ectoplacental cone[56]; at E12.5-E15.5: (CNS; mammary gland; teeth; whisker follicles; limbs)[57] 1C: escapes X inactivation[58,59] |

1A (lid): up-reg in early embryo and metamorph, down-reg in larva 1B;1C;1D: NH 2 (CG3654): up-reg in early embryo, down-reg through adult |

1A; 1C; 1D; 2: NH 1B (rbr-2): early embryonic; developing germline |

|

1A: pituitary; thyroid; testis; ESCs; immunocytes[8] 1B:brain[56]; testis[57]; eye[57]; prostate[57]; ovary[57] 1C: kidney; lung 1D: male-specific thymus; heart[60] 2: brain, kidney; thymus; ESCs |

1A: crop; ovary; larval tubule 2: brain, tubule, ovary, thoracicoabdominal ganglion, male accessory glands |

germline | |||

|

1A;1B;1D: NR 1C: XLMR (human)[61] 2: lethal E15.5 with neural tube defect[62]; SNP associated with schizophrenia (human)[63] |

1A: pupal lethality; small imaginal discs 2: viable; fertile |

vulva developmental defect[31] | |||

| JMJD3 (KDM6) |

UTX UTY JMJD3 |

K27me3/2 |

UTX: escapes X inactivation[64] UTY: ubiquitous (male-specific antigen)[65] 3: down-reg required for neurogenesis[66] |

UTX (CG5640): NR UTY; 3: NH |

UTX (D2021.1): early embryonic; developing germline UTY; 3: NH |

|

UTX: ND UTY: ubiquitous (male-specific antigen)[65] 3: stimulated macrophages[9]; whole blood[8]; pituitary |

brain, ovary, testis, thoracicoabdominal ganglion |

germline | |||

| NR | NR | embryonic lethal; slow growth, small; locomotion abnormal; protruding vulva |

|||

| JMJD6 | PTDSR | H3R2; H4R3 | NR | (psr) | (psr-1): NR |

| brain, eye, spinal cord, thymus, lung, liver, kidney, and intestine[67] |

tubule | NR | |||

| perinatal lethality with lung defect[67]; severe anemia[68] |

NR | apoptotic corpse engulfment defects |

Some demethylases appear to play conserved roles in a particular biological process. For instance, studies in organisms ranging from fission yeast to mice support a role for the H3K4me2/1 demethylase KDM1 (LSD1) in meiosis. The mammalian KDM1/LSD1 shows relatively higher levels of expression in mouse testis and related tissues, complementing the observed lower levels of H3K4me2 in these tissues[4]. Mutations of the fly KDM1 homolog lead to sex-specific embryonic lethality and sterility in the surviving (primarily female) offspring, likely due to defects in ovary development[5]. H3K4me2 levels are higher in the primordial germ cells of heterozygous females and the fly KDM1 protein has in vitro demethylase activity for H3K4me2/1[6], supporting a conservation of enzymatic specificity between mammal and fly. Finally, fission yeast KDM1 homolog mutants are haplo-insufficient for sporulation[7]. Together, these data support a conserved role for KDM1 in meiosis and germ cell development.

Several histone demethylases also display tissue-specific expression. For instance, KDM4B/Jmjd2B expression is restricted to the hematopoietic system and reproductive organs, KDM4C/Jmjd2C and KDM5A/Jarid1A are highly expressed in immune cells, such as T cells, B cells and NK cells; and KDM5B/Jarid1B is almost exclusively present in the reproductive organs[8]. The functional significance of these unique patterns remains to be addressed experimentally.

Demethylase expression can be regulated by extrinsic environmental cues. For example, the newly identified KDM6B/JMJD3, an H3K27me3 demethylase, is the only Jumonji-domain containing protein significantly up-regulated upon treatment with the macrophage-inducing compound LPS[9]. This induction was accompanied by a concurrent reduction of H3K27me3 and activation of Polycomb Group (PcG) target genes, therefore identifying KDM6B/JMJD3 as a potentially integral part of the macrophage trans-differentiation program[9]. Consistent with this finding, KDM6B/JMJD3 was found to be a TPA responsive gene in HL-60 cells[10] and displayed a very specific expression pattern in the hematopoietic system[8].

Intrinsic developmental stimuli can also drive demethylase expression, as seen for the spermatogenesis-induced H3K9me2 demethylase KDM3A/JHDM2A[11]. This testis-specific gene is up-regulated (70-fold) during spermatogenesis, and associates with the Tnp1 and Prm1 promoters, demethylating H3K9me2 and activating these genes required for sperm chromatin packaging[11]. KDM3A/JHDM2A-deficient mice show a defect in post-meiotic chromatin condensation, supporting an essential function for this demethylase in spermatogenesis[11].

Several demethylases also appear to play roles in ESC (embryonic stem cell) self-renewal. For example, KDM4C/Jmjd2C and KDM3A/Jmjd1A were found to be activated by Oct4 in mESCs and are required for mES self-renewal[12]. KDM4C/Jmjd2C and KDM3A/Jmjd1A demethylate H3K9me3 and me2, respectively, at Tcl1 and Nanog promoters in mES cells, hence activating their transcription[12]. The authors propose that upon ESC differentiation, the transcriptional repression of Oct4 results in the loss of KDM4C/Jmjd2C and KDM3A/JmjD1A, facilitating rapid reprogramming at the Tcl1 and Nanog promoters to a silent state[12].

Taken together, these observations suggest that the regulation of demethylase gene expression is critical for their biological activities, as shown by the temporal and tissue-specific expression patterns observed for these enzymes, as well as their induction in response to various stimuli.

Regulation of Demethylase Recruitment

Once present in the cell, demethylase activity must be effectively directed towards target chromatin. This targeting involves both locus-specific recognition (of promoter elements, for example) and local chromatin status assessment. We propose that the activity of a demethylase is controlled in a modular and step-wise fashion, integrating input from protein-protein interactions with DNA binding factors and other chromatin modifying enzymes, recognition of chromatin state by additional non-enzymatic “reader” domains[1] present in the demethylases and/or their associated proteins, as well as possible associations with non-coding RNAs. These inputs allow for a network-based assessment of chromatin environment and allow the demethylases to function as fine-tuners of methylation state. These types of mechanisms may confer specificity for other epigenetic regulators as well.

Demethylases are found in protein complexes containing DNA-binding factors

Biochemical studies have identified the presence of several demethylases in protein complexes with known DNA-binding transcription factors. For instance, the H3K4me3 demethylase KDM5C/JARID1C has been shown to be associated with the DNA-sequence specific REST repressive complex[13], responsible for repression of neuronal genes in non-neuronal tissues. This demethylase has been found to be mutated in patients with X-linked mental retardation, supporting an important role for this activity in regulation of neuronal targets[13,14]. The H3K4me2/1 demethylase KDM1 has been identified in complexes with several known and putative DNA-binding factors including the transcription initiation factor TFII-I[15], the E-cadherin promoter binding factors ZEB1/2[16] and ZNF217[17], as well as Androgen Receptor (AR) [18], suggesting that these DNA-binding factors may play a role in KDM1 recruitment or stabilization at particular loci.

In addition to KDM1, AR also associates with the H3K9me2/1 and H3K9me3 demethylases KDM3A/JHDM2A[19] and KDM4C/JMJD2C[20], respectively, suggesting that AR may regulate multiple demethylases for transcriptional regulation. Intriguingly, the H3K4me3 demethylase KDM5B/JARID1B has also been identified as associated with AR[21]. Although this association would be predicted to act repressively, reporter assays indicated KDM5A enhances AR-mediated activation[21]. Although nuclear receptor dependent targeting of these demethylases has not been specifically confirmed and some demethylases may in fact bind AR responsive promoters constitutively[18,20], the available evidence supports a requirement for AR binding in mediating transcriptional changes on target genes.

Taken together, a number of DNA-binding transcription factors have been implicated in recruiting the various histone demethylases to specific genomic locations. Future experiments will further elucidate the mechanisms by which they recruit the demethylases, and will likely also identify new DNA-binding factors involved in the recruitment.

Demethylase activity can be modulated by DNA-binding transcription factors

Evidence is emerging that transcription factors, in addition to the recruitment role discussed above, can modulate the activities of demethylases and alter their function in transcription regulation. For example, fly KDM5/Lid/JARID1 is an H3K4me3 demethylase, and its mutation leads to de-repression of a large number of genes, consistent with its predicted repressor role[22]. However, the fly Myc homolog was found to interact with the JmjC domain of KDM5/Lid/Jarid1 and this interaction abrogates the demethylase activity of KDM5/Lid[22]. Interestingly, KDM5/Lid exhibits a transcription activator function in this context[22]. How this switch happens at molecular level is still unclear, but may involve changes in complex composition (illustrated in Figure 1B).

Similarly, Wang et. al. found that there are two types of KDM1/LSD1 containing complexes at the Gh promoter in somatotropes and lactotropes, respectively[23]. In somatotropes, actively transcribed Gh is occupied by a KDM1/LSD1-WDR5 containing complex, however, in lactotropes, the Gh promoter is occupied by a ZEB1 -KDM1/LSD1-CoREST-CtBP corepressor complex resulting in transcription repression[23]. Since the induction of ZEB1 correlates with the repression of Gh, the authors propose that ZEB1 binding directs the binding of the corepressive CoREST-CtBP complex to KDM1 that is already present, switching the overall complex to a repressive mode. This model shows parallels to studies done on the AR-responsive promoter PSA, where both KDM1 and KDM4C/JMJD2C are constitutively bound but demethylate H3K9me2/1 only when AR binding is induced[18,20]. These studies suggest a general mechanism where demethylase activity can be regulated by DNA binding factor association. In these situations, the initial targeting and subsequent maintenance of demethylase binding at target gene loci may then be due to yet unidentified DNA-binding factors, RNA factors, local chromatin environment or some as yet unknown mechanism.

Furthermore, transcription factor binding may also alter the substrate specificity of demethylases. For example, KDM1/LSD1 was also shown to participate in demethylation of H3K9me2/1 when complexed with Androgen Receptor (AR)[18]. More recently, KDM1/LSD1 was shown to cooperate with the H3K9me3 demethylase KDM4C/JMJD2C to activate AR-responsive target genes[20]. Similarly, KDM1/LSD1 is linked to an ERα-mediated gene activation program in a ligand-dependent manner, with approximately 58% of ERα+ promoters also exhibiting KDM1/LSD1 recruitment[24]. In this case, KDM1/LSD1 physically associates with ERα, and functionally opposes H3K9 methylases in repressing transcription. However, whether this activation function is due to KDM1/LSD1-mediated H3K9me2 demethylation in response to ERα binding is unclear at present.

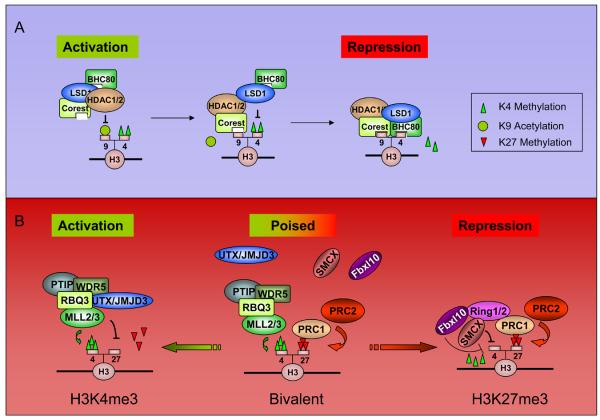

Local chromatin environment regulates demethylase accessibility

KDM1/LSD1 is an example of a demethylase whose chromatin association is extensively modulated by its interaction partners and local histone marks. KDM1/LSD1 was originally identified as a member of the CoREST-containing BRAF-HDAC (BHC) complex, shown to play a role in transcriptional repression of neuronal genes[25,26]. Various members of this complex participate in the activation-to-repression transition of target promoters, in a proposed 4 to 5-step working model for the deacetylation/methylation of H3K9 and demethylation of H3K4 (Figure 2A). First, HDAC1/2 deacetylates H3, allowing for CoREST binding of the hypoacetylated tail[27]. KDM1/LSD1 then demethylates H3K4me2 to me0 in a CoREST-dependent manner[27,28], leading to the observed interplay between HDAC1/2 and LSD1 activity[29]. BHC80 binds H3K4me0, maintaining the complex at the promoter preventing H3K4 remethylation[30]. Finally, G9a/EuMT (which may interact with KDM1/LSD1 via the corepressor CtBP[16]) methylates H3K9me0 to me2, creating a stable mark of repression.

Figure 2. Diagrams of possible epigenetic mechanisms that involved in H3K4me and H3K27me regulation.

A) KDM1/LSD1-mediated H3K4me2 demethylation. A stepwise working model for KDM1/LSD1 complex is illustrated. The whole process involves HDAC-mediated deacetylation, CoREST binding, KDM1/LSD1-mediated H3K4 demethylation and BHC80 binding (H3K4me0). B) A proposed model for resolving bivalent domain to monovalent domain. In the pluripotency stage, the “bivalent domain” is established by MLL and PRC complexes, and the recruitments of H3K27 and H3K4 demethylases are absent. During differentiation, the methylase complexes are selectively kept and demethylases are differentially recruited, resulting in a H3K4me3-only or H3K27me3-only domain.

Recruitment of demethylases can also involve protein-intrinsic qualities (Figure 1, right panel), as exemplified by chromatin-interacting domains such as TUDOR and PHD fingers present in some demethylases. For example, KDM5C/SMCX was found to interact with H3K9 methylases and its PHD finger binds H3K9me3, which may couple KDM5C/SMCX-mediated H3K4 demethylation to H3K9 methylation[13,14,31,32]. The double TUDOR domain of the H3K36/9me3/2 demethylase KDM4A/JMD2A[33-36] has been shown to bind H3K4me3 and H4K20me3[37], suggesting an intrinsic relationship among these methylation marks. We speculate that, while DNA-binding factors may play a primary role in recruiting histone demethylases, the local chromatin environment may provide an additional level of selectivity conferred by protein modules that recognize specific histone modifications. Many demethylases have PHD finger domains or are associated with proteins that have these domains. Although their binding specificities remain undetermined, these activities may be important for initiation and/or maintenance of the demethylase complexes at specific chromosomal environments.

Demethylases coordinate with other epigenetic events

Epigenetic regulation involves integration of multiple chromatin-modifying activities in a coordinated fashion. The examples include the KDM1/LSD1/HDAC complex, as mentioned earlier, and the UTX/MLL H3K27me3 (KDM6) demethylase complex, which also contains WDR5, RBQ3 and Ash2L[38], proteins that are known to be important for H3K4 trimethylation. The presence of KDM6A/UTX and MLL in the same complex suggests a model whereby the removal of the repressive H3K27me3 is coordinated with the addition of the activating modification H3K4me3 (Figure 2B, left). In support of this, KDM6A/UTX morpholino knockdown in zebrafish[39] results in a phenotype similar to that of the WDR5 knockdown in Xenopus[40], as both have defects in Hox gene expression. Similarly, KDM6B/JMJD3 also associates with factors required for H3K4 methylation and is involved in Hox activation[39,41]. These data suggests that H3K4 trimethylation and H3K27 demethylation are coupled for the proper activation of certain Hox genes via members of the KDM6A(UTX)/MLL or KDM6B(JMJD3)/MLL complex. Moreover, demethylases are also likely to be involved in the developmentally programmed silencing of PcG targets. Ring1a/b, originally identified as components of PcG effector complex PRC1, have been isolated in complexes containing H3K4me3 demethylases KDM5C/SMCX[13,42] and KDM2B/Fbxl10[43]. Similarly, the related demethylase KDM5D/SMCY interacts with the polycomb-like protein Ring6a[42]. These findings point to the intrinsic relationship between H3K27 demethylation and H3K4 trimethylation, and suggest the existence of a molecular program where KDM6A(UTX)/MLL or KDM6B(JMJD3)/MLL complexes oppose H3K27me3 and promote H3K4me3 to resolve the “poised” or “bivalent domain” to an active state (Figure 2B, right) These complexes can therefore be considered as controlling a binary switch between activation and repression for the transcriptional regulation of Hox genes as well as potentially other developmentally important H3K27me3-regulated genes.

A role for non-coding RNAs in demethylase recruitment?

Non-coding RNAs appear to represent yet another sequence –based therefore highly specific recruitment mechanism in epigenetic regulation. For example, Xist and the newly identified HOTAIR were found to associate with the PRC2 complex and play important roles in H3K27me3 patterning in silencing the inactive X chromosome and the HOX gene loci, respectively[44,45]. Since H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 demethylation are likely to be coupled, it will be interesting to examine whether non-coding RNAs also play roles in recruiting H3K4 demethylase complexes to establish locus specific epigenetic patterns. As more and more non-coding RNAs are being discovered, their recruitment roles are likely to be broadened.

Post-translation Modifications of Demethylases

A final level of regulation only beginning to be explored is post-translational modifications of the demethylases. Proteomic analyses in HeLa cells have identified phosporylated residues on several demethylases, including the H3K4me3 demethylases KDM5A/JARID1A and KDM5C/JARID1C[46,47], the H3K4me2 demethylase KDM1/LSD1[47], the H3K27me3 demethylase KDM6A/UTX[46], and the H3K9me2 demethylase KDM3A/JMJD1A[46]. Phosphorylated KDM6A/UTX was also identified in the mouse developing brain[48]. Although no data currently exist on the biological relevance of these modifications, their presence suggests that these demethylases are likely to be subjected to the regulation by various signaling pathways. These modifications may play roles in regulating demethylase activity, protein-protein interactions, protein stability or subcellular localization. Finding the kinases and phosphatases functioning upstream of demethylases will help to integrate epigenetic machineries into the proteomic and signaling networks that connect the various cellular activities.

Conclusions

We have summarized our current knowledge of demethylases regarding their expression patterns, recruitment mechanisms, local chromatin environment and cofactor-dependent regulation of their function. We suggest that recruitment plays a critical role in demethylase biology and speculate that local chromatin environments, such as specific histone modifications recognized by specific protein modules built into the demethylases or associated proteins, offer additional selectivity for demethylase recruitment. We propose that post-translational modifications of demethylases themselves, an as yet poorly explored area, may also play a role in modulating demethylase function. A better understanding of these different mechanisms that impact demethylase functions will not only significantly advance demethylase biology, but also contribute to a better understanding of how histone methylation marks are generated, maintained as well as dynamically regulated.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Wysocka J. Methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3: intricacy of writing and reading a single epigenetic mark. Mol Cell. 2007;25:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, Casero RA. Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004;119:941–953. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.012. This study identified the first lysine demethylase, human LSD1, and examined its role in gene repression. This finding showed that lysine methylation is enzymatically reversible and highlighted the dynamic nature of histone lysine methylation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Warren ME, Borchers CH, Tempst P, Zhang Y. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature. 2006;439:811–816. doi: 10.1038/nature04433. The authors were the first to show demethylase activity for a second class of enzymes, the JmjC (jumonji) domain-containing proteins. Many JmjC domain proteins have since been studied, leading to the identification of multiple demethylases with varied substrate specificities and biological roles. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godmann M, Auger V, Ferraroni-Aguiar V, Di Sauro A, Sette C, Behr R, Kimmins S. Dynamic regulation of histone H3 methylation at lysine 4 in mammalian spermatogenesis. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:754–764. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.062265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Stefano L, Ji JY, Moon NS, Herr A, Dyson N. Mutation of Drosophila Lsd1 Disrupts H3-K4 Methylation, Resulting in Tissue-Specific Defects during Development. Curr Biol. 2007;17:808–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudolph T, Yonezawa M, Lein S, Heidrich K, Kubicek S, Schafer C, Phalke S, Walther M, Schmidt A, Jenuwein T, et al. Heterochromatin formation in drosophila is initiated through active removal of H3K4 methylation by the LSD1 homolog SU(VAR)3-3. Mol Cell. 2007;26:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.025. [6;7] both describe regulatory functions of LSD1 homologs in fruit flies and fission yeast, presumably through their demethylase activities towards H3K4me and H3K9me, respectively. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lan F, Zaratiegui M, Villen J, Vaughn MW, Verdel A, Huarte M, Shi Y, Gygi SP, Moazed D, Martienssen RA. S. pombe LSD1 homologs regulate heterochromatin propagation and euchromatic gene transcription. Mol Cell. 2007;26:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.023. *see ref [6] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su AI, Cooke MP, Ching KA, Hakak Y, Walker JR, Wiltshire T, Orth AP, Vega RG, Sapinoso LM, Moqrich A, et al. Large-scale analysis of the human and mouse transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4465–4470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012025199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Santa F, Totaro MG, Prosperini E, Notarbartolo S, Testa G, Natoli G. The histone H3 lysine-27 demethylase Jmjd3 links inflammation to inhibition of polycomb-mediated gene silencing. Cell. 2007;130:1083–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.019. JMJD3 expression is significantly induced in macrophage transdifferentiation, which leads to H3K27me3 demethylation at PcG target loci. This effect is due to JMJD3 recruitment to the promoter accompanied by transcriptional activation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu LY, Tepper CG, Lo SH, Lin WC. An efficient strategy to identify early TPA-responsive genes during differentiation of HL-60 cells. Gene Expr. 2006;13:179–189. doi: 10.3727/000000006783991791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okada Y, Scott G, Ray MK, Mishina Y, Zhang Y. Histone demethylase JHDM2A is critical for Tnp1 and Prm1 transcription and spermatogenesis. Nature. 2007;450:119–123. doi: 10.1038/nature06236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loh YH, Zhang W, Chen X, George J, Ng HH. Jmjd1a and Jmjd2c histone H3 Lys 9 demethylases regulate self-renewal in embryonic stem cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2545–2557. doi: 10.1101/gad.1588207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tahiliani M, Mei P, Fang R, Leonor T, Rutenberg M, Shimizu F, Li J, Rao A, Shi Y. The histone H3K4 demethylase SMCX links REST target genes to X-linked mental retardation. Nature. 2007;447:601–605. doi: 10.1038/nature05823. [13;14;31;32] identify a JMJC domain-containing H3K4me3 demethylase family. Biological links to X-linked Mental Retardation, neuronal development and cellular proliferation as well as molecular connections to DNA-binding factors and histone modifier cofactors were also investigated. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwase S, Lan F, Bayliss P, de la Torre-Ubieta L, Huarte M, Qi HH, Whetstine JR, Bonni A, Roberts TM, Shi Y. The X-linked mental retardation gene SMCX/JARID1C defines a family of histone H3 lysine 4 demethylases. Cell. 2007;128:1077–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.017. *see ref [13] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakimi MA, Dong Y, Lane WS, Speicher DW, Shiekhattar R. A candidate X-linked mental retardation gene is a component of a new family of histone deacetylase-containing complexes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7234–7239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi Y, Sawada J, Sui G, Affar el B, Whetstine JR, Lan F, Ogawa H, Luke MP, Nakatani Y. Coordinated histone modifications mediated by a CtBP co-repressor complex. Nature. 2003;422:735–738. doi: 10.1038/nature01550. This study reveals a molecular connection between histone deacetylases and H3K9 methylases, and these authors therefore propose a model for coordination between histone modifiers in chromatin regulation. The CtBP supercomplex appears to have two subcomplexes; one containing HDAC, LSD1, CoREST and BHC80 and the other one with REST, G9a and EuMT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cowger JJ, Zhao Q, Isovic M, Torchia J. Biochemical characterization of the zinc-finger protein 217 transcriptional repressor complex: identification of a ZNF217 consensus recognition sequence. Oncogene. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metzger E, Wissmann M, Yin N, Muller JM, Schneider R, Peters AH, Gunther T, Buettner R, Schule R. LSD1 demethylates repressive histone marks to promote androgen-receptor-dependent transcription. Nature. 2005;437:436–439. doi: 10.1038/nature04020. The authors identified an unexpected activity of LSD1 towards H3K9me2 upon AR binding in a ligand-dependent manner. This “activating” LSD1 is recruited to AR target promoters and activates gene transcription. This is also the first observation of an alteration in demethylase substrate specificity by cofactor binding. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamane K, Toumazou C, Tsukada Y, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Wong J, Zhang Y. JHDM2A, a JmjC-containing H3K9 demethylase, facilitates transcription activation by androgen receptor. Cell. 2006;125:483–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wissmann M, Yin N, Muller JM, Greschik H, Fodor BD, Jenuwein T, Vogler C, Schneider R, Gunther T, Buettner R, et al. Cooperative demethylation by JMJD2C and LSD1 promotes androgen receptor-dependent gene expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:347–353. doi: 10.1038/ncb1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiang Y, Zhu Z, Han G, Ye X, Xu B, Peng Z, Ma Y, Yu Y, Lin H, Chen AP, et al. JARID1B is a histone H3 lysine 4 demethylase up-regulated in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19226–19231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700735104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Secombe J, Li L, Carlos L, Eisenman RN. The Trithorax group protein Lid is a trimethyl histone H3K4 demethylase required for dMyc-induced cell growth. Genes Dev. 2007;21:537–551. doi: 10.1101/gad.1523007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Scully K, Zhu X, Cai L, Zhang J, Prefontaine GG, Krones A, Ohgi KA, Zhu P, Garcia-Bassets I, et al. Opposing LSD1 complexes function in developmental gene activation and repression programmes. Nature. 2007;446:882–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05671. This study was done using a conditional knock out mouse model to study LSD1 function in pituitary organogenesis. A lineage-specific regulation of LSD1 complex composition was found, and this alteration can switch LSD1 complex function from gene activation to repression. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Bassets I, Kwon YS, Telese F, Prefontaine GG, Hutt KR, Cheng CS, Ju BG, Ohgi KA, Wang J, Escoubet-Lozach L, et al. Histone methylation-dependent mechanisms impose ligand dependency for gene activation by nuclear receptors. Cell. 2007;128:505–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.038. This study and the study in [7] provide genome-wide localization analyses of LSD1 and its homologs. Both studies found LSD1 and its homolog primarily participated in gene activation programs, through its role in antagonizing H3K9me. This study [24] also reveals an involvement of LSD1 in ER-α mediated transcription activation upon ligand stimulation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.You A, Tong JK, Grozinger CM, Schreiber SL. CoREST is an integral component of the CoREST- human histone deacetylase complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1454–1458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hakimi MA, Bochar DA, Chenoweth J, Lane WS, Mandel G, Shiekhattar R. A core-BRAF35 complex containing histone deacetylase mediates repression of neuronal-specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7420–7425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112008599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi YJ, Matson C, Lan F, Iwase S, Baba T, Shi Y. Regulation of LSD1 histone demethylase activity by its associated factors. Mol Cell. 2005;19:857–864. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.027. [27-30] These studies focus on the molecular involvement of CoREST, HDAC1/2 and BHC80 in LSD1-mediated H3K4me2 demethylation. They reveal criticial roles of CoREST in nucleosomal substrate demethylation and BHC80 in histone tail (H3K4me0) tethering of the complex post-demethylation. In addition, the PHD finger of BHC80 also represents the first example of an me0 “Reader” in humans, with a structural explanation provided. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee MG, Wynder C, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. An essential role for CoREST in nucleosomal histone 3 lysine 4 demethylation. Nature. 2005;437:432–435. doi: 10.1038/nature04021. *see ref [27] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee MG, Wynder C, Bochar DA, Hakimi MA, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Functional interplay between histone demethylase and deacetylase enzymes. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6395–6402. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00723-06. *see ref [27] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lan F, Collins RE, De Cegli R, Alpatov R, Horton JR, Shi X, Gozani O, Cheng X, Shi Y. Recognition of unmethylated histone H3 lysine 4 links BHC80 to LSD1-mediated gene repression. Nature. 2007;448:718–722. doi: 10.1038/nature06034. *see ref [27] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christensen J, Agger K, Cloos PA, Pasini D, Rose S, Sennels L, Rappsilber J, Hansen KH, Salcini AE, Helin K. RBP2 belongs to a family of demethylases, specific for tri-and dimethylated lysine 4 on histone 3. Cell. 2007;128:1063–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.003. *see ref [13] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamane K, Tateishi K, Klose RJ, Fang J, Fabrizio LA, Erdjument-Bromage H, Taylor-Papadimitriou J, Tempst P, Zhang Y. PLU-1 is an H3K4 demethylase involved in transcriptional repression and breast cancer cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.001. *see ref [13] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whetstine JR, Nottke A, Lan F, Huarte M, Smolikov S, Chen Z, Spooner E, Li E, Zhang G, Colaiacovo M, et al. Reversal of histone lysine trimethylation by the JMJD2 family of histone demethylases. Cell. 2006;125:467–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.028. [33-36] These groups independently identified the first tri-methyl demethylase family. The JMJD2 family contains 4 members which exhibit similar activities towards H3K9me3 and H3K36me3 substrates. These discoveries highlighted the enzymatically reversible nature of lysine tri-methylation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klose RJ, Yamane K, Bae Y, Zhang D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Wong J, Zhang Y. The transcriptional repressor JHDM3A demethylates trimethyl histone H3 lysine 9 and lysine 36. Nature. 2006;442:312–316. doi: 10.1038/nature04853. *see ref [33] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cloos PA, Christensen J, Agger K, Maiolica A, Rappsilber J, Antal T, Hansen KH, Helin K. The putative oncogene GASC1 demethylates tri- and dimethylated lysine 9 on histone H3. Nature. 2006;442:307–311. doi: 10.1038/nature04837. *see ref [33] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fodor BD, Kubicek S, Yonezawa M, O'Sullivan RJ, Sengupta R, Perez-Burgos L, Opravil S, Mechtler K, Schotta G, Jenuwein T. Jmjd2b antagonizes H3K9 trimethylation at pericentric heterochromatin in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1557–1562. doi: 10.1101/gad.388206. *see ref [33] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang Y, Fang J, Bedford MT, Zhang Y, Xu RM. Recognition of histone H3 lysine-4 methylation by the double tudor domain of JMJD2A. Science. 2006;312:748–751. doi: 10.1126/science.1125162. The double Tudor domain of JMJD2A was found to bind H3K4me3 and a co-crystal structure was resolved as well. The JMJD2C double tudor domain also showed a strong H3K4me3 binding (F. Lan and Y. Shi, unpublished results). Due to the high sequence similarity, JMJD2B is presumably to be able bind H3K4me3 as well. This finding suggests a connection between H3K4me3 binding and H3K9/K36me3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee MG, Villa R, Trojer P, Norman J, Yan KP, Reinberg D, Di Croce L, Shiekhattar R. Demethylation of H3K27 regulates polycomb recruitment and H2A ubiquitination. Science. 2007;318:447–450. doi: 10.1126/science.1149042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lan F, Bayliss PE, Rinn JL, Whetstine JR, Wang JK, Chen S, Iwase S, Alpatov R, Issaeva I, Canaani E, et al. A histone H3 lysine 27 demethylase regulates animal posterior development. Nature. 2007;449:689–694. doi: 10.1038/nature06192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wysocka J, Swigut T, Milne TA, Dou Y, Zhang X, Burlingame AL, Roeder RG, Brivanlou AH, Allis CD. WDR5 associates with histone H3 methylated at K4 and is essential for H3 K4 methylation and vertebrate development. Cell. 2005;121:859–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agger K, Cloos PA, Christensen J, Pasini D, Rose S, Rappsilber J, Issaeva I, Canaani E, Salcini AE, Helin K. UTX and JMJD3 are histone H3K27 demethylases involved in HOX gene regulation and development. Nature. 2007;449:731–734. doi: 10.1038/nature06145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee MG, Norman J, Shilatifard A, Shiekhattar R. Physical and functional association of a trimethyl H3K4 demethylase and Ring6a/MBLR, a polycomb-like protein. Cell. 2007;128:877–887. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frescas D, Guardavaccaro D, Bassermann F, Koyama-Nasu R, Pagano M. JHDM1B/FBXL10 is a nucleolar protein that represses transcription of ribosomal RNA genes. Nature. 2007;450:309–313. doi: 10.1038/nature06255. These authors provide evidence of H3K4me3 demethylase activity for FBXL10 both in vitro and in vivo, and identify roles in cell growth regulation and rRNA gene repression. Note: the H3K4me3 activity claimed by this study is inconsistent to that determined by an earlier study [3]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plath K, Fang J, Mlynarczyk-Evans SK, Cao R, Worringer KA, Wang H, de la Cruz CC, Otte AP, Panning B, Zhang Y. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in X inactivation. Science. 2003;300:131–135. doi: 10.1126/science.1084274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rinn JL, Kertesz M, Wang JK, Squazzo SL, Xu X, Brugmann SA, Goodnough LH, Helms JA, Farnham PJ, Segal E, et al. Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin domains in human HOX loci by noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2007;129:1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beausoleil SA, Jedrychowski M, Schwartz D, Elias JE, Villen J, Li J, Cohn MA, Cantley LC, Gygi SP. Large-scale characterization of HeLa cell nuclear phosphoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12130–12135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ballif BA, Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Schwartz D, Gygi SP. Phosphoproteomic analysis of the developing mouse brain. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:1093–1101. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400085-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McColl G, Killilea DW, Hubbard AE, Vantipalli MC, Melov S, Lithgow GJ. Pharmacogenetic Analysis of Lithium-induced Delayed Aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:350–357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705028200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pothof J, van Haaften G, Thijssen K, Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Ahringer J, Plasterk RH, Tijsterman M. Identification of genes that protect the C. elegans genome against mutations by genome-wide RNAi. Genes Dev. 2003;17:443–448. doi: 10.1101/gad.1060703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ko SY, Kang HY, Lee HS, Han SY, Hong SH. Identification of Jmjd1a as a STAT3 downstream gene in mES cells. Cell Struct Funct. 2006;31:53–62. doi: 10.1247/csf.31.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katoh M. Comparative integromics on JMJD1C gene encoding histone demethylase: conserved POU5F1 binding site elucidating mechanism of JMJD1C expression in undifferentiated ES cells and diffuse-type gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:219–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoog C, Schalling M, Grunder-Brundell E, Daneholt B. Analysis of a murine male germ cell-specific transcript that encodes a putative zinc finger protein. Mol Reprod Dev. 1991;30:173–181. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080300302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Katoh Y, Katoh M. Comparative integromics on JMJD2A, JMJD2B and JMJD2C: preferential expression of JMJD2C in undifferentiated ES cells. Int J Mol Med. 2007;20:269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang D, Yoon HG, Wong J. JMJD2A is a novel N-CoR-interacting protein and is involved in repression of the human transcription factor achaete scute-like homologue 2 (ASCL2/Hash2) Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6404–6414. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6404-6414.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frankenberg S, Smith L, Greenfield A, Zernicka-Goetz M. Novel gene expression patterns along the proximo-distal axis of the mouse embryo before gastrulation. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Madsen B, Spencer-Dene B, Poulsom R, Hall D, Lu PJ, Scott K, Shaw AT, Burchell JM, Freemont P, Taylor-Papadimitriou J. Characterisation and developmental expression of mouse Plu-1, a homologue of a human nuclear protein (PLU-1) which is specifically up-regulated in breast cancer. Mech Dev. 2002;119(Suppl 1):S239–246. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carrel L, Hunt PA, Willard HF. Tissue and lineage-specific variation in inactive X chromosome expression of the murine Smcx gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1361–1366. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.9.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sheardown S, Norris D, Fisher A, Brockdorff N. The mouse Smcx gene exhibits developmental and tissue specific variation in degree of escape from X inactivation. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1355–1360. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.9.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Isensee J, Witt H, Pregla R, Hetzer R, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Ruiz Noppinger P. Sexually dimorphic gene expression in the heart of mice and men. J Mol Med. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0240-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jensen LR, Amende M, Gurok U, Moser B, Gimmel V, Tzschach A, Janecke AR, Tariverdian G, Chelly J, Fryns JP, et al. Mutations in the JARID1C gene, which is involved in transcriptional regulation and chromatin remodeling, cause X-linked mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:227–236. doi: 10.1086/427563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takeuchi T, Yamazaki Y, Katoh-Fukui Y, Tsuchiya R, Kondo S, Motoyama J, Higashinakagawa T. Gene trap capture of a novel mouse gene, jumonji, required for neural tube formation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1211–1222. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pedrosa E, Ye K, Nolan KA, Morrell L, Okun JM, Persky AD, Saito T, Lachman HM. Positive association of schizophrenia to JARID2 gene. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144:45–51. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greenfield A, Carrel L, Pennisi D, Philippe C, Quaderi N, Siggers P, Steiner K, Tam PP, Monaco AP, Willard HF, et al. The UTX gene escapes X inactivation in mice and humans. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:737–742. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.4.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Greenfield A, Scott D, Pennisi D, Ehrmann I, Ellis P, Cooper L, Simpson E, Koopman P. An H-YDb epitope is encoded by a novel mouse Y chromosome gene. Nat Genet. 1996;14:474–478. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jepsen K, Solum D, Zhou T, McEvilly RJ, Kim HJ, Glass CK, Hermanson O, Rosenfeld MG. SMRT-mediated repression of an H3K27 demethylase in progression from neural stem cell to neuron. Nature. 2007;450:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature06270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li MO, Sarkisian MR, Mehal WZ, Rakic P, Flavell RA. Phosphatidylserine receptor is required for clearance of apoptotic cells. Science. 2003;302:1560–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1087621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kunisaki Y, Masuko S, Noda M, Inayoshi A, Sanui T, Harada M, Sasazuki T, Fukui Y. Defective fetal liver erythropoiesis and T lymphopoiesis in mice lacking the phosphatidylserine receptor. Blood. 2004;103:3362–3364. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]