Abstract

We tested the prediction that self-control will have buffering effects for adolescent substance use (tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana) with regard to three risk factors: family life events, adolescent life events, and peer substance use. Participants were a sample of public school students (N = 1,767) who were surveyed at four yearly intervals between 6th grade and 9th grade. Good self-control was assessed with multiple indicators including planning and problem solving. Results showed that the impact of all three risk factors on substance use was reduced among persons with higher scores on good self-control. Buffering was found in cross-sectional analyses with multiple regression and in longitudinal analyses in a latent growth model with time-varying covariates. Implications for addressing self-control in prevention programs are discussed.

Keywords: self-control, substance use, adolescents, buffering effect, growth modeling

Self-Control as a Buffering Agent for Adolescent Substance Use

This research investigated the role of self-control for buffering the impact of risk factors on adolescent substance use. A buffering effect has been defined as a process such that having a certain characteristic reduces the impact of risk factors on outcomes. For example, Werner (1986) followed a sample of children who grew up in difficult life circumstances (e.g., poverty and parental alcohol abuse) and found that children with a more affectionate temperamental style showed lower levels of adverse outcomes (e.g., substance abuse and mental health problems) in young adulthood. This type of moderation, where the risk factor is a background of adverse life circumstances, is also known as resilience and shows that adverse circumstances do not necessarily lead to substance abuse and other disorder (Garmezy, 1993; Werner & Smith, 1992).

Subsequent research has shown evidence of resilience effects for adolescent behavior problems (Masten & Powell, 2003; Wyman, Sandler, Wolchik, & Nelson, 2000). Several studies have focused on temperament as a factor in child behavior problems, finding evidence of interactions with stress measures for temperament dimensions such as resistance to control (Bates, Pettit, Dodge, & Ridge, 1998) or composite scores representing difficult vs. easy-going temperamental style (Smith & Prior, 1995). In these studies, the impact of risk factors on behavior problems was reduced among children with a positive temperamental style. However, there is still limited understanding of how such processes work and there has been relatively little research on buffering effects for adolescent substance use.

Self-control concepts may offer an avenue for understanding buffering effects for substance use. Complex self-control abilities are based on earlier temperament characteristics, and in adolescence, self-control characteristics affect exposure to proximal risk factors for substance use (Wills & Ainette, in press). Prior research has demonstrated a replicated measurement structure for self-control constructs representing good self-control (or planfulness) and poor self-control (or impulsiveness), which are inversely related but not strongly correlated (e.g., Wills, Cleary, Filer, Shinar, Mariani, & Spera, 2001; Wills, Walker, Mendoza, & Ainette, 2006). Findings on main effects from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies conducted in various populations have been consistent in showing that individuals who score higher on good self-control (e.g., indices of planning, problem solving, and future time perspective) have lower levels of tobacco and alcohol use (Brody & Ge, 2001; Novak & Clayton, 2001; Wills & Stoolmiller, 2002). In addition, studies conducted in late adolescence and young adulthood have shown that self-control indices are related to substance abuse problems (Patock-Peckham, Cheong, Balhorn, & Nagoshi, 2001; Simons & Carey, 2002; Wills, Sandy, & Shinar, 1999).

While main effects of self-control are of interest, several aspects of the good self-control construct have properties that may be relevant for moderation effects. For example, planning and forethought could help persons anticipate and prepare for troublesome situations, and problem solving could help them see alternative solutions to problems that arise and use interpersonal skills to deal with them. Emotional self-regulation could provide better emotional control in problem situations, as well as enabling individuals to avoid ruminating about negative emotions after an adverse event has occurred. The ability to restrain action in problem situations, and avoid saying things to provoke people when upset or irritated, are important components of social self-control, where an important goal is to accommodate others and achieve solutions without antagonizing persons who could otherwise help solve problems (Unger, Sussman, & Dent, 2003). Having such abilities should be reflected in risk factors having less impact on substance use for persons who are relatively high on good self-control, that is, a buffering effect.

Previous studies have shown main effects of self-control for substance use but there has been less attention to the possible role of such processes for contributing to buffering effects. One study (Hussong & Chassin, 2004) examined buffering effects of coping variables measured in young adulthood (18-23 years) on substance use in a high-risk sample. Tests of interactions of stress-coping indices with two stress measures (major life events and transition-related stress) showed major life stress was related to drug use at a low level of active coping but not at a high level of active coping, so this represents a buffering effect. Dishion and Connell (2006) tested temperament measures linked to self-control (e.g., inhibition, attention), assessed at ages 16-17 years, in relation to behavior problems at age 18-19 years. They found that this composite reduced the impact of peer deviance and negative life events on externalizing and internalizing behavior. However, these studies were focused on emerging adulthood and the question of buffering effects for substance use needs further examination, particularly in early adolescence.

In the present research we tested for moderation effects of self-control on three types of risk factors: Family life events (those occurring directly to a family member), adolescent life events (those occurring directly to the adolescent him/herself), and peer substance use (tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana). Life stress has consistently been shown to be a risk factor for adolescent substance use (e.g., Whalen, Jamner, Henker, & Delfino, 2001; Wills, Sandy, & Yaeger, 2002), and peers’ smoking and drinking is a recognized risk factor for substance use among adolescents (e.g., Hoffman, Sussman, Unger, & Valente, 2006; Wills & Cleary, 1999). Though individual self-control abilities might be less relevant for moderating some types of risk factors (e.g., parental substance abuse), problem solving can be important for helping reduce the impact of negative life events, the elements of planning and restraint may be useful in helping persons deal with peer pressure situations, and characteristics such as flexibility in trying alternative solutions may help to reduce the adverse impact of family events that are beyond the adolescents’ control (e.g., parental unemployment--Unger, Hamilton, & Sussman, 2004). Having a higher level of goal-setting and persistence could also lessen adverse consequences of events for which the adolescent might have some causal responsibility (e.g., getting bad grades in school--Bryant, Schulenberg, O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 2003). In the present research, an inventory measured major life events occurring during the past year, including events occurring to family members as well as events occurring directly to the adolescent him/herself. Peer substance use was assessed through determining the number of the participant’s friends who used tobacco, alcohol, or marijuana. We studied the role of good self-control for moderating the impact of these risk factors on a composite score for substance use involvement.

The analytic approach was based on a growth model with time-varying covariates. Substance use in early adolescence tends to increase over time, and repeated measures of substance use typically are fit well by a latent growth model in which observations of substance use at various time points are specified as indicators of intercept and slope constructs (e.g., Wills, Sandy, Yaeger, Cleary, & Shinar, 2001). In principle, a buffering effect in the longitudinal context could be manifested by measures of good self-control at an early time point reducing the long-term rate of growth in substance use, particularly among adolescents with a high level of stress. However there is reason to believe that a dynamic process could operate over shorter time periods, reducing the impact of current life stressors so as to improve an adolescents’ functioning over a time period such as a year but not having trait-like effects that extend over long time periods (cf. Wills, Resko, Ainette, & Mendoza, 2004). Hence a buffering effect (i.e., less change in substance use among higher-risk participants) could be observed over a shorter time period but would not necessarily be observed for the long-term growth trajectory. Accordingly we used an analytic model including a measure of self-control at each time point and its interaction with current life events (i.e., time-varying covariates), regressed on substance use concurrently and one year later. This allows for detection of buffering effects operative over shorter time periods.

In summary, we investigated buffering effects of self-control prospectively over the period from 11 to 15 years of age, a time of particular relevance because early onset of substance use is prognostic for substance abuse or dependence at later ages (e.g., Anthony & Petronis, 1995; Hawkins, Graham, Maguin, Abbott, Hill, & Catalano, 1997). The primary hypothesis was that good self-control will serve as a buffering agent, reducing the impact of negative life events and peer substance use on adolescents’ substance use. This hypothesis was investigated in a diverse sample of youth in a 4-wave study that obtained multiple indicators of self-control. We conducted cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses to test for moderation effects of self-control for onset and escalation of substance use, with control for demographic characteristics.

Method

Participants

The participants were from public school districts in a metropolitan area. The districts are in mixed urban-suburban communities that are socioeconomically representative of the state population (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2002). The sample was surveyed four times at yearly intervals. The baseline sample (N = 1,810 participants) consisted of students in 6th grade classes in a total of 18 elementary schools. In 7th grade and 8th grade, participants were in six junior high schools, and in 9th grade, the participants were in five high schools. In the first wave, mean age of the participants was 11.5 years (SD 0.6); mean ages at subsequent assessments were 12.6 years, 13.5 years, and 14.6 years. The sample was 50% female and 50% male. Ethnic background was 27% African-American, 23% Hispanic, 3% Asian-American, 36% Caucasian, 7% other ethnicity, and 5% mixed ethnicity. Regarding family structure, 56% of the participants were living with two biological parents, 34% were with a single parent, and 10% were in a blended family (one biological parent and one stepparent). Father’s education on a 1-6 scale had M = 4.1 (SD = 1.4), a level just above some college.

Procedure

Students participated under a procedure in which parents were informed about the nature and methods of the study through a notice sent by direct mail. The parent was informed that he/she could have the child excluded from the research if he/she wished, either by contacting a designated administrator at the school or by returning a self-addressed postcard to the investigator. Students not excluded by parents were similarly informed about the research prior to survey administration through a written description and were informed that they could refuse or discontinue participation. Written assent was obtained from students who chose to participate. The study procedures and measures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Data were obtained through a self-report questionnaire administered to students in classrooms by trained research staff using a standardized protocol. The questionnaire took approximately 40 minutes to administer. After giving standardized instructions to students, staff members circulated in the classroom to answer any individual questions about particular items. The survey was administered under confidential conditions, and a Certificate of Confidentiality protecting the data was obtained from the Department of Health and Human Services. Students were instructed that they should not write their name on the survey, and were assured their answers were strictly confidential and would not be shown to their parents or teachers. Methodological research has shown that when participants are assured of confidentiality, self-reports of substance use have good validity (e.g., Patrick et al., 1994). In the baseline assessment each participant was assigned a numerical code. In subsequent years, the data collectors administered a survey with the same code number to the appropriate respondent by verifying the student’s name with the teacher at the time of survey administration. The student’s name was printed on a tear-off sheet that was removed from the questionnaire when it was given to the student, so protocols were identified only by an arbitrary code number. Prior to data entry the surveys were examined by editors and a code was assigned for probable invalid responding based on specified criteria (e.g., zig-zag patterns, going down one scale point for more than one page). This resulted in 1-2% of the protocols being excluded from data analyses.

Sampling

The sampling frame for the study was all English-speaking students in the school population. For the baseline (6th grade) assessment, the sample size was 1,810 and the completion rate was 94%, with nonparticipation occurring because of parental exclusion (1%), student refusal (1%), or absenteeism or unavailability because of other school activities (4%). In subsequent years, students new to the school were surveyed as well as original study participants. For the 7th grade assessment the sample size was 1,882 and the completion rate was 88% with 4% parental exclusion, 3% student refusal, and 5% student absenteeism. For the 8th grade assessment the sample size was 1,818 and the completion rate was 86% with 3% parental exclusion, 5% student refusal, and 6% student absenteeism. For the 9th grade assessment the sample size was 1,796 and the completion rate was 84% with 3% parental exclusion, 6% student refusal, and 7% student absenteeism. The total number of persons who participated in the study for at least one wave was 2,808. Data on retention for the original (6th grade) participants, allowing dropout at one wave but participation at three others, indicated that 72% provided usable data over the four waves of the study.

Measures

Participants completed a self-report questionnaire that included identical measures at all four waves of the study. Scale structure was verified with factor analysis (principal-factor method, varimax rotation) followed by internal consistency analysis (Cronbach alpha). All scales were constructed such that a higher score represents more of the named attribute.

Demographics

Items asked about age, gender, and ethnicity (5 options, multiple responding allowed). The family composition item asked what adult(s) the participant currently lived with (8 options, multiple responding allowed), and was recoded for analysis to three categories (intact family, single-parent family, or blended family). Items about education for father and mother had a 1-6 response scale with response points from Grade School to Post-College (masters or doctoral degree or other professional education). Father’s education was used because preliminary analyses indicated it had stronger relations with substance use.

Good self-control

Good self-control was assessed with a composite score based on several types of items. Seven items were from an inventory on generalized self-control in everyday situations (see Kendall & Wilcox, 1979). This included items on soothability (e.g., “I can easily calm down when I am excited or wound up”), dependability (“When I promise to do something, you can count on me to do it”), planning (“I like to plan things ahead of time”), and tendency to reflect and deliberate before acting (“I usually think before I act”). Responses were on 5-point Likert scales (“Not at all True for Me” to “Very True for Me”). Eight items were from an inventory on responses in problem situations at school or home (see Wills, McNamara, Vaccaro, & Hirky, 1996). Sample items are “When I have a problem, I make a plan of action and follow it” and “When I have a problem, I try different ways to solve the problem.” Responses were on 5-point frequency scales (“Never” to “Often”). A composite score with a possible range of 15-75 was based on the simple (unweighted) sum of the items. Alpha for the 15-item composite was .83 in 6th grade, .86 in 7th grade, .87 in 8th grade, and .88 in 9th grade.

Negative life events

In a 20-item checklist of negative events (Wills et al., 1996), the participant was asked to indicate (No/Yes) whether or not a given event had occurred during the previous year. The checklist included an 11-item index on family life events, those that occurred to a family member and were unlikely to have been caused by the adolescent him/herself (e.g., “My father/mother: had a serious illness / lost his/her job / had a serious accident / had problems with money”). The checklist also had a 9-item index on adolescent life events, those that occurred directly to the adolescent and could have been caused by the adolescent him/herself (e.g., “I had a serious accident,” “I broke up with a girl/boy friend,” “I got in trouble with the police,” “I got disciplined or suspended in school”). Composite scores for family events and adolescent events were based on the simple (unweighted) sum of the number of events reported. These were indices rather than psychometric scales so internal consistency was not computed.

Peer substance use

Three items asked the participant whether any of his/her friends smoked cigarettes, drank beer/wine, or smoked marijuana (Newcomb & Bentler, 1988). Responses were on 5-point scales with response points None, One, Two, Three, and Four or More. The measure was scored for a 3-item composite with a possible range of 0-12. Alphas were .75, .83, .87, and .87 for 6th through 9th grade, respectively.

Participant’s substance use

Substance use by the participant was measured with items that asked about the typical frequency of his/her cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use. Three items were introduced to participants with the stem: “How often do you smoke cigarettes / drink alcohol / smoke marijuana?” Responses were on 6-point scales with scale points Never Used, Tried Once-Twice, Used Four-Five Times, Usually Use a Few Times a Month, Usually Use a Few Times a Week, and Usually Use Every Day. A fourth item asked the participant whether there was a time in the last month when he/she had three or more drinks on one occasion; response points were No, Happened Once, and Happened Twice or More. The substance use items were intercorrelated and the correlations increased with age (cf. Hays, Widaman, DiMatteo, & Stacy, 1987; Needle, Su, & Lavee, 1989). Accordingly, substance use was scored for a 4-item composite with a possible range of 0-17; alphas were .63, .75, .82, and .84 for 6th through 9th grade, respectively.

Analytic Approach

To test for buffering effects on a cross-sectional basis, multiple regression analyses were performed for each of the four assessment points, with the composite substance use score from a given assessment as the criterion variable. The regression models included concurrent main-effect terms for the self-control measure and a risk factor (either life events or peer substance use) and the cross-product of the two variables. These models included a binary index for gender (coded 0 = female, 1 = male); two binary indices for ethnicity (African American [1] vs. Hispanic or Caucasian [0], and Hispanic [1] vs African-American or Caucasian [0]); two binary indices for family structure (single [1] vs. blended or intact [0], and blended [1] vs. single or intact [0]), and a 6-point scale for parental education. Cases with Asian, other, or mixed ethnicity were excluded in the coding procedure for the ethnicity indices because of small cell size in the case of Asians and ambiguous interpretation in the case of other or multiple ethnicity, which included a number of ethnic groups or combinations. The analytic sample size for these analyses was in the range from 1,400 to 1,500, with case loss occurring because of the ethnicity coding and missing data on other variables. Interactions were graphed by computing predicted values of substance use for cases at M +/- 1 SD on the self-control measure and the risk factor.

To address substance use in a longitudinal context, latent growth curve analysis was employed using a structural equation modeling framework (Willett & Sayer, 1994). The observed values of the composite score for substance use at 6th grade, 7th grade, 8th grade, and 9th grade were specified as a growth model with constructs for intercept, the initial level of substance use, and slope, the rate of change in use over time. Intercept was specified by setting the loadings of the four observed values of substance use on the intercept construct to 1, and slope was specified by setting the loadings of the four observed values of substance use on the slope construct to 0, 1, 2, and 3, representing the assumption of linear growth with equal spacing of assessments over time. A covariance of the intercept and slope constructs was also specified. Analyses were performed in Mplus ver. 4.1 employing the maximum likelihood method with the EM algorithm utilized to model missing data (Muthén & Muthén, 2005).1

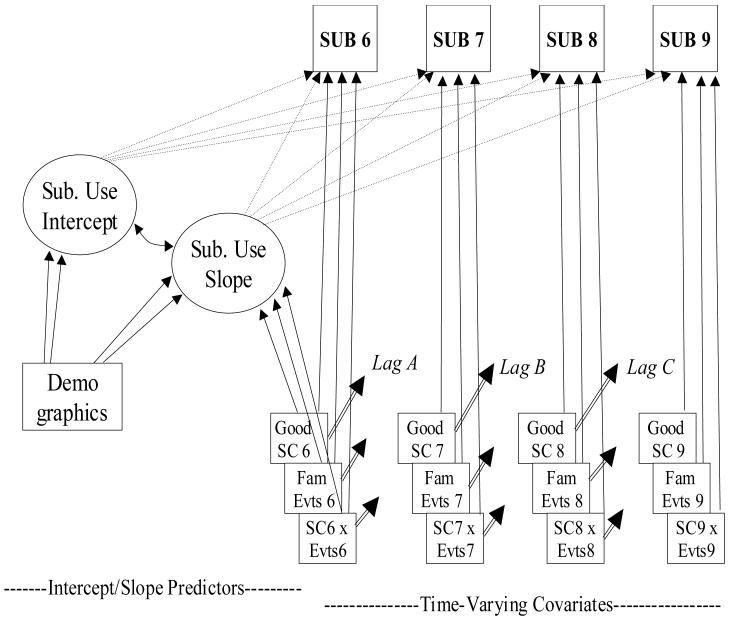

To address buffering effects, a longitudinal model of moderation effects was specified with time-varying covariates; this is similar to model 6.10 in the Mplus manual (Muthén & Muthén, 2005, pp. 85-86) with the addition of cross-product terms. Substance use intercept and slope constructs were based on four assessments of substance use, specified as described previously. The intercept was regressed on demographic variables (gender, ethnicity, family structure, and parental education), coded as described previously. The slope was regressed on the demographic variables and grand-mean centered main-effect terms for baseline level of a risk factor (e.g., family events), good self-control, and their cross-product (e.g., family events × good self-control).2 Correlations of the risk factor measures, self-control measures, and demographic variables were included in the model. Time-varying effects were specified by regressing an observed value of substance use (e.g., substance use at grade 7) on the main effects and cross-product from that time point (e.g., family events grade 7, good self-control grade 7, and their cross-product). This specification produces four sets of time-varying covariates, one set each for grade 6, grade 7, grade 8, and grade 9. Three sets of 1-year lagged effects were also specified by regressing the observed value of substance use at a given time point on the predictors (two main effects and their cross-product) from the previous time point. In the analytic model the Grade 6 predictors had effects on Grade 6 substance use, Grade 7 substance use, and the slope construct. The Grade 7 and Grade 8 time-varying predictors had concurrent effects and 1-year lagged effects on substance use. Because we had no theoretical reason to expect the concurrent or lagged effects of the time-varying predictors to change across grades, they were constrained to be equal across Grades 7-9. The Grade 6 concurrent effects were not constrained to be equal to the Grades 7-9 concurrent effects because at Grade 6 there is no competing 1-year lagged effect as there is at Grades 7-9. If the 1-year lagged effects are important then the Grade 6 concurrent effects are probably overstated, so equality constraints would not be appropriate. The analytic model is illustrated in Figure 1, which portrays the baseline effects on intercept and slope, the effects for the time-varying covariates, and the lagged effects.

Figure 1.

Time-varying model for effects of risk factor and self-control on substance use. Model presented is for family life events. Ovals indicate latent constructs, rectangles indicate manifest variables. Dotted lines indicate specification for intercept and slope constructs. Solid slanted lines indicate paths from demographics, family events, self-control, and their cross-product to intercept and slope constructs. Vertical solid lines indicate effects for time-varying covariates to substance use at each time point. Double slanted lines indicate lagged effects.

Results

Data for substance use indicated that the majority of the participants were nonusers but that use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana increased over time in the study population, with similar increases noted for all types of substance (cf. Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 2002). For example the percentage of participants who had smoked cigarettes four-five times or more was 6% in 6th grade, 19% in 7th grade, 28% in 8th grade, and 33% in 9th grade. Comparable figures for use of alcohol were 9%, 21%, 30%, and 39%, respectively, and for use of marijuana were 1%, 4%, 12%, and 17%, respectively. The observed rates and increases over time are comparable to findings for available studies of substance use in late childhood and early adolescence (Jackson, 1997; Koval, Pederson, Mills, McGrady, & Carvajal, 2000; Oetting & Baeuvais, 1990; Volk, Edwards, Lewis, & Schulenberg, 1996).

Descriptive statistics for the study variables are presented in Table 1. Distributions for the self-control scores were generally normal, with skewness values close to zero. Means for good self-control were slightly above the scale midpoints, producing skewness values that are negative by convention. Data for family life events and adolescent life events were shifted toward lower values, with the average participant having experienced around two events of each type in the previous year; the standard deviations indicated considerable variability around the means. Skewness values for these data are positive by convention and parameters indicated only moderate skew. Data for peer substance use tended toward lower values, with the average participant at 6th grade knowing 1-2 persons who had used substances, but these values increased markedly over time. Level of participants’ substance use was initially low but the mean values also increased substantially over time. Distributions for peer and adolescent use were initially skewed (because most participants had low values) but skewness parameters for these data decreased considerably over time, as rates of peer and adolescent use increased.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables, for 6th Grade through 9th Grade

| Variable/grade | M | SD | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good self-control6 A | 56.13 | 9.69 | -0.37 |

| Good self-control7 | 52.32 | 10.57 | -0.18 |

| Good self-control8 | 51.74 | 10.72 | -0.14 |

| Good self-control9 | 52.04 | 10.84 | -0.19 |

| Family life events6 B | 2.36 | 1.95 | 0.84 |

| Family life events7 | 2.14 | 1.83 | 0.95 |

| Family life events8 | 2.08 | 1.78 | 0.93 |

| Family life events9 | 2.03 | 1.73 | 0.96 |

| Adolescent events6 C | 1.94 | 1.60 | 0.80 |

| Adolescent events7 | 2.11 | 1.64 | 0.65 |

| Adolescent events8 | 2.09 | 1.63 | 0.65 |

| Adolescent events9 | 2.13 | 1.63 | 0.67 |

| Friend substance use6 D | 1.57 | 2.24 | 1.59 |

| Friend substance use7 | 3.68 | 3.99 | 0.84 |

| Friend substance use8 | 5.57 | 4.67 | 0.20 |

| Friend substance use9 | 6.75 | 4.60 | 0.20 |

| Adolescent sub. use6 E | 0.91 | 1.40 | 2.88 |

| Adolescent sub. use7 | 1.85 | 2.48 | 2.28 |

| Adolescent sub. use8 | 2.95 | 3.53 | 1.76 |

| Adolescent sub. use9 | 3.56 | 3.84 | 1.41 |

Possible range = 15-75.

Possible range = 0-10.

Possible range = 0-9.

Possible range = 0-12.

Possible range = 0-17.

Attrition analyses were conducted over 1-, 2-, and 3-wave lags in the longitudinal design, performing t-tests to compare persons who dropped out with those who remained in the sample. Dropouts had higher levels of family life events; regarding substance use, dropouts and stayers did not differ on level of substance use at 6th grade, but did differ (p < .05) in 7th grade and 8th grade, with dropouts having higher levels of use. There were no differences between dropouts and stayers on self-control, and no consistent differences for adolescent events or peer use. In a regression model predicting attrition from 6th grade to 9th grade with demographic controls, the five study variables together accounted for 2% of the variance in attrition; a significant unique effect was noted for family life events (t = 2.32, p < .05) and a marginal effect for peer substance use (t = 1.82, p < .10). Thus there was some evidence of differential attrition but the magnitude of the attrition effect was modest and similar to effects noted in previous research with adolescent samples (e.g., Newcomb & Bentler, 1988).

Cross-Sectional Tests for Buffering Effects

Cross-sectional tests of buffering were performed separately for the measure of family life events, the measure of adolescent life events, and the measure of peer substance use. The correlation of family events and adolescent events ranged over assessments from .41 to .45; the correlation of family events and friend use was .15 to .27; and the correlation of adolescent events and friend use was .33 to .36; hence these variables were somewhat correlated but the magnitude of the correlations indicates the tests are not redundant. The correlation of good self-control with family events ranged from -.10 to -.18, the correlation with adolescent events ranged from -.23 to -.27, and the correlation with peer use ranged from -.22 to -.26, so these variables were correlated but there was not a high degree of collinearity. Results in main-effect models indicated the risk factors had significant relations to substance use at each assessment, with betas in the range of .15 to .20 for family life events, 25 to .35 for adolescent life events, and .50 to .60 for peer substance use (p < .0001 for all). In main-effect models, good self-control had inverse relations to substance use at all points, with betas around -.25 (p < .0001 for all).

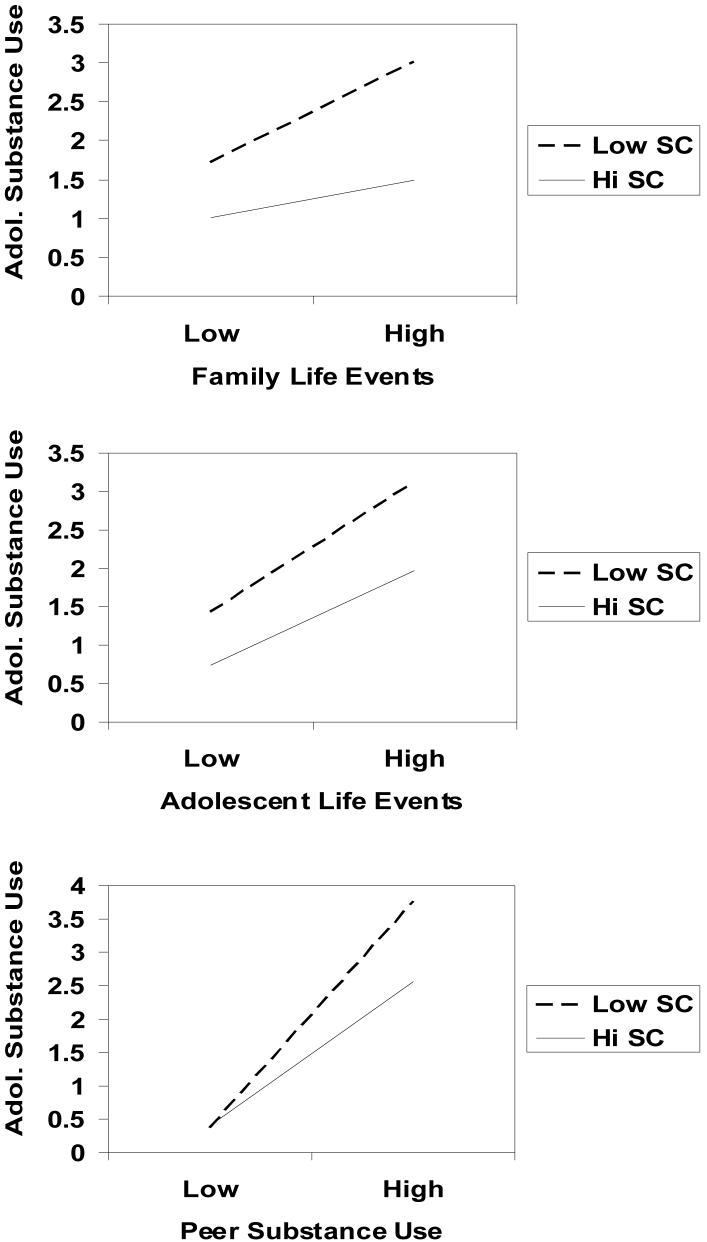

Results for the cross-product term from the interaction models, presented in Table 2, indicated moderation effects for all the risk factors. Interactions were more consistent for peer use and adolescent events than for family events but were significant in almost all cases. Significant interactions were observed for the individual indices of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana, so the buffering effects were not limited to one particular substance. In each case the form of the interaction was a buffering effect: the impact of the risk factor on substance use was reduced among persons with higher scores on good self-control. Examples are illustrated in Figure 2, which presents data from 7th grade. Tests of the simple slopes across waves indicated that among persons with higher scores on good self-control, the effect of risk factors was reduced but was still statistically significant in most cases, so it was generally the case that self-control reduced but did not eliminate the impact of the risk factors.

Table 2.

Tests From Regression Models for Interaction of Self Control (SC) and Risk Factors, for 6th Grade - 9th Grade Data, Substance Use Score as Criterion

| Model | 6th grade | 7th grade | 8th grade | 9th grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good SC x family events | -1.82+ | -3.92**** | -3.20*** | -1.05 |

| Good SC x adolescent events | -3.95**** | -1.67 | -4.61*** | -3.13** |

| Good SC x peer substance use | -8.45**** | -6.09**** | -3.26*** | -3.83**** |

Note: Value is t for cross product term (good self-control x risk factor) in model including two main-effect terms and demographics (gender, ethnicity, family structure, and parental education).

N for analyses is 1,400 - 1,500 approximately.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

p < .0001

Figure 2.

Substance use scores for cases with low vs. high values on self-control measure and risk factor (M +/- 1 SD); based on data from 7th grade. 2A: Good self-control and family events. 2B: Good self-control and adolescent events. 2C: Good self-control and friend substance use.

Comparing the marginal effect for a risk factor at low vs. high levels of self-control (M +/- 1 SD) at the four assessment points provides an index of the moderation effect size. For family life events, the effect at a high level of good self-control was reduced 46%-67% from the effect at a low level of good self-control (M = 58% reduction). For adolescent events, the effect at a high level of self-control was reduced 35%-67% from the effect at low self-control (M = 49% reduction). For peer substance use, the effect at a high level of self-control was reduced 20%-47% from the effect at a low level of self-control (M = 33% reduction). Averaging over the three risk factors, the average reduction in impact of the risk factors was 61% in 6th grade, 44% in 7th grade, 42% in 8th grade, and 40% in 9th grade, so the moderating effect of good self-control was largest at the youngest age but was roughly comparable at later ages.

Longitudinal Model with Time-Varying Covariates

The latent-growth measurement model as described previously was analyzed in Mplus. The observed substance use measures were specified as indicators of intercept and slope constructs. Observed values of substance use in the analytic sample were 0.89, 1.84, 2.97, and 3.80 for 6th through 9th grades, respectively. The measurement model had chi-square (5, N = 1,767) of 41.91, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = .95, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = .065. Thus a model based on the specification of linear growth had reasonable fit.3 The mean intercept parameter was 0.88 (SE 0.04) and the variance of the intercept was 1.56 (SE 0.21), both parameters being significantly different from zero. The mean slope was 1.00 (SE 0.03) and its variance was 1.27 (SE 0.10), with both parameters being different from zero. In this model the correlation of the intercept and slope constructs was r = 0.20.

For the analytic model with time-varying covariates, three separate models were analyzed and specified as described previously to test for buffering effects of good self-control with regard to family events, adolescent events, and peer substance use, respectively. Each model was estimated using maximum likelihood with robust estimates of standard errors. The model for family life events had reasonably good fit to the data, with chi-square (51, N = 1,767) of 169.92, CFI of .94, and RMSEA of .036. In this model the correlation of the intercept and slope constructs was r = .15. Results from this model are presented in Table 3A. For demographic variables, male gender was positively related to substance use intercept; effects for ethnicity indicated lower initial levels of use and lower slopes for both Black and Hispanic adolescents; and single and blended family structure both were positively related to slope. There were significant effects on substance use slope in this model for both family events and good self-control (with opposite signs) but there was no interaction effect for the slope construct.

Table 3.

Results for Self-Control (SC) and Three Risk Factors in Model with Time-Varying Covariates

| b | SE | t | b | SE | t | b | SE | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paths to Intercept Construct | A. | Family | Events | B. | Adol. | Events | C. | Peer Sub. | Use |

| Male --> Intercept | .154 | .070 | 2.20* | .072 | .069 | 1.04 | .195 | .055 | 3.57*** |

| Black B> Intercept | -.256 | .098 | 2.60** | -.268 | .095 | 2.83** | -.164 | .073 | 2.23* |

| Hispanic B> Intercept | -.224 | .096 | 2.35* | -.188 | .094 | 2.00* | -.131 | .070 | 1.88 |

| Paths to Slope Construct | |||||||||

| Black --> Slope | -.453 | .083 | 5.48**** | -.427 | .079 | 5.38**** | -.301 | .068 | 4.40**** |

| Hispanic --> Slope | -.241 | .080 | 3.02** | -.223 | .078 | 2.86** | -.135 | .068 | 1.99* |

| Single --> Slope | .195 | .076 | 2.56** | .220 | .071 | 3.10** | .191 | .062 | 3.07** |

| Blended --> Slope | .333 | .105 | 3.17** | .359 | .096 | 3.73*** | .211 | .087 | 2.41** |

| Risk factor6 --> Slope | .055 | .022 | 2.55** | .106 | .026 | 4.11**** | .089 | .019 | 4.81**** |

| Good SC6 --> Slope | -.097 | .036 | 2.66** | -.051 | .037 | 1.37 | .015 | .069 | 0.21 |

| Risk fact.6 x SC6 --> Slope | -.001 | .020 | 0.02 | .012 | .022 | 0.57 | -.019 | .017 | 1.10 |

| Effects to 6th Grade Substance Use | |||||||||

| Risk factor6 --> Sub. use6 | .125 | .022 | 5.62**** | .233 | .025 | 9.51**** | .369 | .021 | 17.15**** |

| Good SC6 --> Sub. use6 | -.334 | .040 | 8.33**** | -.277 | .038 | 7.25**** | -.462 | .083 | 5.59**** |

| Risk fact.6 x SC6 --> Sub. use6 | -.045 | .024 | 1.91 | -.088 | .025 | 3.52*** | -.102 | .022 | 4.69**** |

| Time-Varying Substance Use (7, 8, 9) on: | |||||||||

| Concurrent risk factor | .197 | .028 | 6.93**** | .344 | .033 | 10.56**** | .289 | .013 | 22.88**** |

| Concurrent Good SC | -.306 | .046 | 6.66**** | -.254 | .047 | 5.42**** | -.206 | .046 | 4.48**** |

| Concurrent Risk x SC | -.085 | .035 | 2.43** | -.097 | .037 | 2.66** | -.043 | .012 | 3.60*** |

| Lagged Substance Use (7, 8, 9) on: | |||||||||

| 1-year prior risk factor | .052 | .029 | 1.79 | .097 | .031 | 3.08** | .121 | .017 | 7.30**** |

| 1-year prior good SC | -.295 | .048 | 6.19**** | -.241 | .047 | 5.17**** | -.307 | .056 | 5.47**** |

| 1-year prior risk x SC | -.084 | .028 | 2.96** | -.122 | .027 | 4.44**** | -.044 | .012 | 3.59*** |

Note: Values are unstandardized coefficients (SE in parentheses). Analyses based on 1,767 participants. Participant gender and parental education were included in all models but were nonsignificant

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

p < .0001

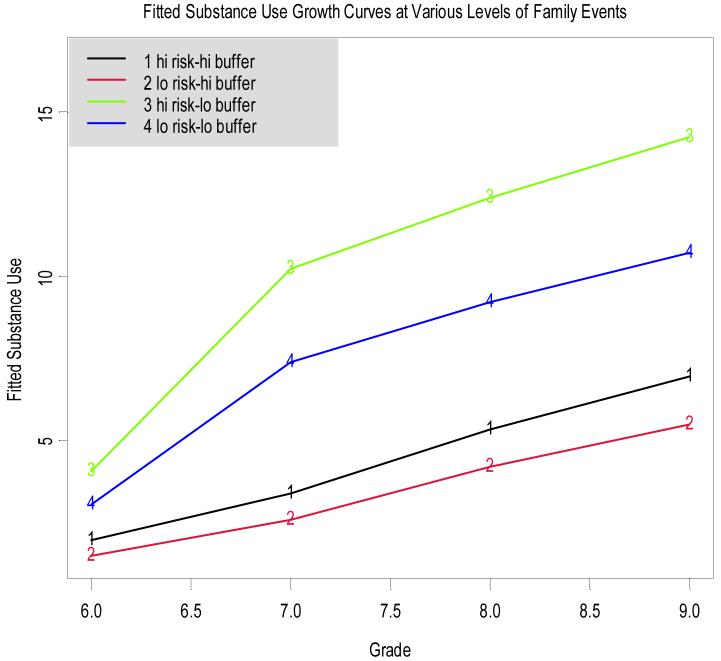

Regarding the time-varying covariates, for 6th grade there were significant main effects for family events and good self-control on substance use (in opposite directions) and the interaction term was marginal at this assessment (t = 1.91, p < .10). For the time-varying effects at other assessments the paths for main and interaction effects were significant. Good self-control was inversely related to substance use, family events was positively related to substance use, and their interaction was significant with inverse sign, indicating a buffering effect; that is, the impact of family events on concurrent substance use was reduced among persons with higher scores on good self-control. In the lagged tests the main effect of family events was not significant but the main effect for self-control and the interaction term were significant. This indicates that good self-control was inversely related to change in substance use over 1-year lagged periods, and there was less impact of family events on change in substance use among persons with higher scores on good self-control. This effect is independent of the effects of baseline variables (demographics and family events) on the slope construct.4 Model-computed growth curves for persons with different levels of self-control and family life events, which incorporate both concurrent and lagged effects, are presented in Figure 3. The figure illustrates how change in substance use over time was reduced among persons with higher scores on good self-control, and this effect was larger among persons with higher levels of family events.

Figure 3.

Substance use growth curves for persons with low vs. high scores on good self-control (15th and 85th percentiles) and for low vs. high level of family life events.

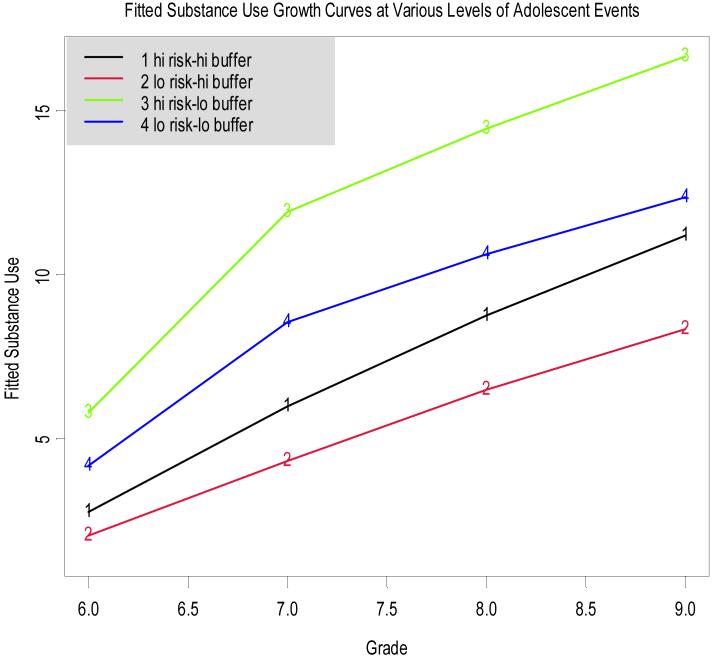

The model for adolescent events had chi-square (51, N = 1,767) of 181.70, CFI of .94, and RMSEA of .038, again indicating reasonably good fit to the observed data. In this model the correlation of intercept and slope was r = .15. Results for this model are presented in Table 3B. In this model, where self-control had a higher correlation with the risk factor, adolescent life events at baseline was positively related to substance use slope, with greater rate of growth in substance use for persons with more events, but no main effect for self-control was found and there was no interaction effect for the slope construct. The 6th grade effects and time-varying main effects in this model were all significant. Adolescent events were positively related to substance use, good self-control was inversely related to substance use, and the interaction of self-control with adolescent events on concurrent substance use was significant with inverse sign at 6th grade and in subsequent tests, indicating a buffering effect. Lagged main and interaction effects were also significant, indicating that good self-control reduced the effect of adolescent life events on increase in substance use over 1-year periods. Again, this is independent of the effects of baseline predictors (demographics and adolescent events) on the slope construct. Model-computed growth curves for participants with varying levels of life events and self-control are presented in Figure 4. The figure illustrates how a higher level of good self-control was related to less change in substance use over time, and particularly so for persons with higher levels of negative events.

Figure 4.

Substance use growth curves for persons with low vs. high scores on good self-control (15th and 85th percentiles) and for low vs. high level of adolescent life events.

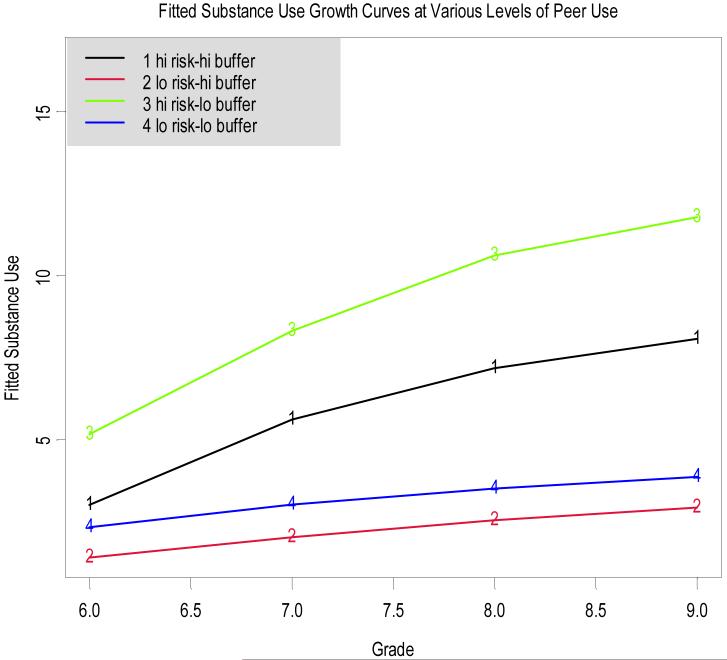

The model for peer substance use had chi-square (51, N = 1,767) of 140.81, CFI of .97, and RMSEA of .032, indicating good fit of the model to the data. In this model the correlation of intercept and slope was r = .11. Results for this analysis are presented in Table 3C. There was a significant effect of peer use on substance use slope, with a higher rate of growth among persons with more substance-using friends, but there was no main effect for self-control and no interaction effect for substance use slope. The effects for time-varying covariates and lagged analyses were all significant. Effects for 6th grade and time-varying effects showed peer use was positively related to adolescent substance use, good self-control was inversely related to substance use, and there was significant interaction for concurrent substance use. Significant interaction in the lagged tests indicated less impact of peer use on change in adolescent substance use over time, particularly for persons with higher levels of peer use, and this was independent of the effect of demographics and baseline peer use on the slope construct. Model-computed substance use growth curves for persons with different levels of peer use and self-control are presented in Figure 5. This illustrates that change in adolescents’ substance use was attenuated, particularly among persons with high peer use and a high level of good self-control.5

Figure 5.

Substance use growth curves for persons with low vs. high scores on good self-control (15th and 85th percentiles) and for low vs. high level of peer substance use.

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to test a theoretical perspective suggesting that good self-control can function as a buffering agent. This was investigated through determining whether adolescents with higher self-control scores were less affected by risk factors for substance use. The study utilized a measurement model in which good self-control was assessed with multiple indicators, and we tested interaction effects for three types of risk factors. Analyses of data obtained over the period from early to middle adolescence were consistent with prediction in showing buffering effects of self-control, which were found for two types of life events and for peer substance use. For each risk factor, individuals with higher scores on good self-control showed less impact of the risk factor on their level of substance use, both concurrently and longitudinally. The findings were based on data from a large multiethnic sample of adolescents and included control for demographic characteristics.

This study was focused on the age range from 11-15 years, a period when there are changes in many aspects of adolescents’ lives and there can be substantial exposure to various types of risk factors. The findings showed buffering effects occurring across this developmental period. Cross-sectional analyses indicated buffering was more pronounced for early-onset use, but buffering effects were observed throughout the study period. A longitudinal analysis with time-varying covariates supported this conclusion; there were longitudinal effects over 1-year periods, with good self-control reducing the impact of risk factors on change in substance use.

We note that while the growth model analyses showed significant effects of risk factors on the latent construct for substance use slope, they did not consistently show an effect of self-control on the slope construct. While elevated initial levels of life events and peer use predicted the overall pattern of growth in substance use, this was not the case for good self-control. We note however that the slope construct is based on a 3-year period, and the time-varying effects showed a significant buffering effect for good self-control over 1-year time periods. The suggestion is that patterns of life stress and peer relationships represent contextual characteristics that are relatively more stable over time, even though there may be some changes in the events and the peers (Hoffman et al., 2006; Wills & Cleary, 1999; Zucker, 1994). In contrast, individual cognitions and self-control characteristics are developing throughout adolescence (Gibbons, Gerrard, & Lane, 2003; Stuss, 1992; Tarter et al., 1999) and it is the level of self-control ability at a given point in time that appears most relevant for buffering the impact of adverse events that are occurring at that time. Hence an individual’s level of good self-control at each year during early adolescence is significant for affecting the impact of risk factors on outcomes over the next year, and during adolescence each year can count.

There are aspects of the study that are possible limitations. The measures of substance use reflected total frequency of use, and further research could study buffering effects with diagnostic measures of substance abuse or dependence. The data were based on self-reports of friends’ substance use, and this method can be extended by obtaining multiple sources of data. There was differential attrition from the study, comparable to that found in other longitudinal investigations of adolescents (Wills, Walker, & Resko, 2005), and while this generally works against finding significant effects there is a need for attention to substance use among the most deviance-prone participants. The sample was studied over one part of adolescence, and studies conducted at other time points would help to clarify where buffering effects are most prominent.

Self-Control and Resilience Effects

The present research was based on an approach that considered how components of self-control can function as generalized resources that are relevant for dealing with life problems as well as day-to-day interactions and social pressures. The results are consistent with this formulation because observations of buffering effects indicate that good self-control operated to reduce the adverse impact of several risk factors. The research focused on three different types of risk factors with somewhat different characteristics. Family events such as financial strains may be more remote from the daily life of the adolescent (though they definitely have an impact on him/her--Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994), whereas peer behavior is a more immediate factor in adolescents’ daily lives. The effect size for family events was lower than that for peer use but it should be noted that the family events measure was quite heterogeneous in nature. The results also showed buffering effects of good self-control for adolescent life events, which to some extent may have been caused by the adolescent him/herself. This suggests that components such as problem solving may help to counter the adverse effects of events attributable to impulsive actions, thus producing buffering among individual attributes (cf. Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, & Reiser, 2000; Wills, Windle, & Cleary, 1998). Determining what types of events have the most impact on adolescents and their substance use is a question to be investigated in further research (Seidman & Pedersen, 2003; Zucker, 1994).

In this study the self-control measure was based on several indicators but it should be noted that there are other aspects of self-control and these may also be relevant for buffering. These include aspects such as delay of gratification (Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989), future time perspective (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999), and self-reinforcement (Heiby, 1983). Recent research has also delineated affective lability and emotional self-control as domains of processes that are related to substance use (Simons & Carey, 2006; Wills et al., 2006). Including additional indicators of individual and social self-control (Sussman, McCuller, & Dent, 2003) could help to expand the scope of research on buffering effects for substance use and other problem behaviors.

Buffering effects may be most common for controllable risk factors that can be countered by thoughtfulness, persistence, and flexibility combined with some degree of restraint in problem situations (Carver, 2005; Wills & Dishion, 2004). However, there may be risk factors that are not easily or appropriately ameliorated by this process. For example, child abuse is a risk factor that can not easily be countered by the child, and coping mechanisms based on seeking help outside the family may be more appropriate. A risk factor such as parental substance abuse has the elements of abusiveness and unpredictability, so adolescents’ functioning may be enhanced by relationships with peers or supportive adults, and the adverse impact of racial discrimination may be countered by parental socialization about how to deal with arbitrary treatment by others (Gibbons, Gerrard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004; Wills et al., 2007). Poverty is a risk factor outside the child’s control but resilience research has shown a wide range of outcomes among persons growing up in difficult conditions, so one can not rule out the role of individual characteristics for enhancing adaptation to these types of stressors (Masten & Powell, 2003). Considering how the impact of various risk factors can or cannot be ameliorated by individual or environmental characteristics is a question that needs to be further elaborated (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Windle, 1999).

The findings have implications for prevention through suggesting that self-control characteristics may contribute to resilience effects (Masten & Powell, 2003; Wyman et al., 2000). There are also implications for substance use prevention programs (Miller & Brown, 1991; Wills & Dishion, 2004). Though individual self-control characteristics cannot eliminate the impact of all risk factors, self-control research focuses on strategies that are potentially modifiable. While there is evidence that aspects such as attentional control begin to develop in early childhood (Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000) there is also evidence indicating that self-control abilities continue to develop through adolescence (Rothbart & Rueda, 2005; Stuss, 1992). Self-control training programs have been tested with good results for depression (Rehm, Kaslow, & Rubin, 1987), and alcohol problems (Walters, 2000). In addition, research with children has shown training in components of self-control related to better outcomes in school settings (Diamond, Barnett, Thomas, & Munro, 2007; Zimmerman, 2000). Thus there is reason to include self-control components with other evidence-based prevention approaches, and test their effectiveness for enhancing good self-control and reducing the impact of impulsiveness and poor decision making. Such research could help to elucidate cognitive and social processes through which self-control is related to substance use and develop methods for enhancing self-control abilities, thereby reducing the impact of factors that could lead to substance use (Brody et al., 2005; Gerrard et al., 2006; Gibbons et al., 2003; Wills & Ainette, in press). The results from time-varying analyses in the present research suggest that level of good self-control is important throughout the period from 11 to 15 years of age, thus providing a rationale for continued preventive intervention throughout this developmental period.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants R01 DA08880 and R01 DA12623 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

We thank the district superintendents and school principals for their support, and the parents and youth participants for their cooperation.

Footnotes

Similar effects of predictors on constructs were noted for tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use even though absolute levels were different (cf. Wills & Cleary, 1999), hence analyses were performed for a composite score. The analytic sample was participants who had two or more data points for substance use over the study and were of Black, Hispanic, or White ethnicity (N = 1,767 cases). We did not analyze all surveyed cases because some contributed only one wave.

For the analysis the self-control measure was standardized at each point because a different response scale was used for problem solving in 6th grade than at later time points. In the descriptive statistics (Table 1) this is corrected so that all descriptives are in the same metric.

Model fit could have been improved somewhat by including a correlated error among the substance use indicators or by freeing a factor loading for the slope construct to accommodate a slight nonlinearity in the data. However, model fit was reasonable to begin with and the goal was to keep the time-varying model as simple as possible. Including these modifications in the time-varying models did not change any of the results for the time-varying predictors.

The constrained models were compared with unconstrained models in which time-varying effects of the predictors were allowed to vary. These comparisons showed no significant difference in fit for the family events model, difference chi-square (12) = 9.70, ns, or for the peer use model, difference chi-square (12) = 17.56, ns, though the constrained model for adolescent events did not fit as well, difference chi-square (12) = 27.64, p = .01. Examination of the concurrent and lagged interaction terms in the unconstrained models indicated that in each model 4 of the 7 interaction terms were significant, though somewhat different ones across models.

The low vs. high values used for the computed curves were time-constant values of 0 and 6 for family events and 0 and 5 for adolescent events. For peer use, which changed markedly over time, values were 0, 0, 0, 0 (low) and 6, 11, 12, 12 (high). At 9th grade, 30% of the sample scored at the top level, so there was some censoring for this variable.

References

- Anthony JC, Petronis KR. Early-onset drug use and risk of later drug problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;40:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Ridge B. Interaction of temperamental resistance to control and restrictive parenting in the development of externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:982–995. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody G, Ge X. Linking parenting and self-regulation to psychological functioning and alcohol use during early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;2001:82–94. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, McNair L, Chen Y-F, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Wills TA. Linking changes in parenting to relationship quality and youth self-control. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15:47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant AL, Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. How academic achievement and attitudes relate to the course of substance use during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:361–397. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CE. Impulse and constraint: Perspectives from personality psychology. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2005;9:312–333. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0904_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger R, Ge X, Elder G, Lorenz F, Simons R. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65:541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, Barnettt WS, Thomas J, Munro S. Preschool program improves cognitive control. Science. 2007;318:1387–1388. doi: 10.1126/science.1151148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Connell A. Adolescents’ resilience as a self-regulatory process. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1094:125–138. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes R, Guthrie I, Reiser M. Emotionality and regulation: Their roles in social functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:136–157. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N. Vulnerability and resilience. In: Funder DC, Parke RD, editors. Studying lives through time: Personality and development. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1993. pp. 377–398. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Brody GH, Murry VM, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA. A theory-based dual-focus alcohol intervention for preadolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:185–195. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Lane DJ. A social reaction model of adolescent health risk. In: Suls JM, Wallston KA, editors. Social psychological foundations of health and illness. Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2003. pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody GH. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African-American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:517–529. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Graham JW, Maguin E, Abbott R, Hill KG, Catalano RF. Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:28–290. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Widaman KF, DiMatteo MR, Stacy AW. Structural equation models of drug use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiby EM. Assessment of frequency of self-reinforcement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44:1304–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman BR, Sussman S, Unger JB, Valente TW. Peer influences on adolescent smoking: A theoretical review. Substance Use and Misuse. 2006;41:103–155. doi: 10.1080/10826080500368892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Chassin L. Stress and coping among children of alcoholic parents through the young adult transition. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:985–1006. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C. Initial and experimental stages of tobacco and alcohol use during late childhood. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22:685–698. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Secondary school students. Vol. 1. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2002. National survey results on drug use from the Monitoring the Future study, 1975-2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Wilcox LE. Self-control in children: Development of a rating scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:1020–1029. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT, Harlan ET. Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:220–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koval JJ, Pederson LL, Mills CA, McGrady GA, Carvajal SC. Models of the relationship of stress, depression, and other psychosocial factors to smoking behavior: A comparison of a cohort of student in Grades 6 and 8. Preventive Medicine. 2000;30:463–477. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Powell JL. A resilience framework for research, policy, and practice. In: Luthar S, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2003. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Brown JM. Self-regulation as a conceptual basis for the prevention of addictive behaviors. In: Heather N, Miller WR, Greeley J, editors. Self-control and the addictive behaviors. Maxwell Macmillan; Sydney, Australia: 1991. pp. 3–79. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Shoda Y, Rodriguez ML. Delay of gratification in children. Science. 1989;244:933–938. doi: 10.1126/science.2658056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus User’s Guide. Author; Los Angeles, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Needle R, Su S, Lavee Y. A comparison of the empirical utility of three composite measures of adolescent drug involvement. Addictive Behaviors. 1989;14:429–441. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Impact of adolescent drug use and social support on problems of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:64–75. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak SP, Clayton RR. Influence of school environment and self-regulation on transitions between stages of cigarette smoking. Health Psychology. 2001;20:196–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Beauvais F. Adolescent drug use: Findings of national and local surveys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:385–394. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Cheong J-W, Balhorn ME, Nagoshi CT. A model of parenting styles, self-regulation, perceived drinking control, and alcohol use and problems. Alcoholism: Experimental and Clinical Research. 2001;25:1284–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick D, Cheadle A, Thompson D, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1086–1093. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm LP, Kaslow NJ, Rubin AS. Cognitive/behavioral targets in a self-control program for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:60–67. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Rueda MR. The development of effortful control. In: Mayr U, Awh E, Keele S, editors. Developing individuality in the human brain. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2005. pp. 156–188. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman E, Pedersen S. Contextual perspectives on risk, protection, and competence among low-income urban adolescents. In: Luthar S, editor. Resilience and vulnerability. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2003. pp. 318–342. [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Carey KB. Risk and vulnerability for marijuana use problems: The role of affect dysregulation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:72–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Carey KB. An affective and cognitive model of marijuana and alcohol problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1578–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Prior M. Temperament and resilience in school-age children: A family study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:168–179. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199502000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuss DT. Biological and psychological development of executive functions. Brain and Cognition. 1992;20:8–23. doi: 10.1016/0278-2626(92)90059-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, McCuller WJ, Dent CW. The association of social self-control with drug use among high-risk youth. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1159–1166. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Giancola P, Dawes M, Blackson T, Mezzich A, Clark D. Etiology of early age onset substance use disorder: A maturational perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:657–683. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Hamilton JE, Sussman S. Family member’s job loss as a risk factor for smoking among adolescents. Health Psychology. 2004;23:308–313. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Sussman S, Dent CB. Interpersonal conflict tactics and substance use among high-risk adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:979–987. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00290-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Commerce . 2000 Census of the population: General population characteristics (New York) Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Volk RJ, Edwards DW, Lewis RA, Schulenberg J. Smoking and brand preference among adolescents. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1996;8:347–359. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(96)90197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters GD. Behavioral self-control training for problem drinkers: A meta-analysis of controlled studies. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE. Resilient offspring of alcoholics: A longitudinal study from birth to age 18. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1986;47:34–40. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1986.47.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE, Smith RS. Overcoming the odds: High risk children from birth to adulthood. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Whalen CK, Jamner JD, Henker B, Delfino RJ. Smoking and moods in adolescents with depressive and aggressive dispositions. Health Psychology. 2001;20:99–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett JB, Sayer AG. Using covariance structure analysis to detect correlates and predictors of change over time. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:363–381. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Ainette MG. Temperament, self-control, and adolescent substance use: A two-factor model of etiological processes. In: Scheier LM, editor. Handbook of drug use etiology. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Cleary SD. Peer and adolescent substance use among 6th-10th graders: Latent growth analyses of influence vs. selection. Health Psychology. 1999;18:453–463. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Cleary SD, Filer M, Shinar O, Mariani J, Spera K. Temperament and self-control related to early-onset substance use. Prevention Science. 2001;2:145–163. doi: 10.1023/a:1011558807062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Dishion TJ. Adolescent substance use: A transactional analysis of emerging self-control. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:69–81. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, McNamara G, Vaccaro D, Hirky AE. Escalated substance use: A longitudinal grouping analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:166–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Murry VM, Brody GH, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Walker C, Ainette MG. Racial socialization, ethnic pride, and self-control related to protective and risk factors: Test of the theoretical model for the Strong African-American Families Program. Health Psychology. 2007;26:50–59. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Resko J, Ainette M, Mendoza D. Smoking onset in adolescence: A person-centered analysis with time-varying predictors. Health Psychology. 2004;23:158–167. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Shinar O. Cloninger’s constructs and substance use problems in adolescence: A mediational model based on self-control and coping motives. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7:122–134. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger AM. Stress and smoking in adolescence: A test of directional hypotheses with latent growth analysis. Health Psychology. 2002;21:122–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger AM, Cleary SD, Shinar O. Coping dimensions, life stress, and adolescent substance use: A latent growth analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:309–323. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Stoolmiller M. The role of self-control in early escalation of substance use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:986–997. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Walker C, Mendoza D, Ainette MG. Behavioral and emotional self-control: Relations to substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:265–278. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Walker C, Resko JA. Longitudinal studies of drug use and abuse. In: Sloboda Z, editor. Epidemiology of drug abuse. Springer; New York: 2005. pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Windle M, Cleary SD. Temperament and novelty-seeking in adolescent substance use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:387–406. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. Critical conceptual and methodological issues in the study of resilience. In: Glantz MD, Johnson JL, editors. Resilience and development. Kluwer Academic-Plenum Publishers; New York: 1999. pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman PA, Sandler I, Wolchik S, Nelson K. Resilience as cumulative competence promotion and stress protection. In: Cicchetti D, Rappaport J, Sandler I, Weissberg RP, editors. The promotion of wellness in children and adolescents. CWLA Press; Washington, DC: 2000. pp. 133–184. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbardo PG, Boyd JN. Time perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:1271–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman BJ. Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In: Boekaerts M, Pintrich PR, Zeidner M, editors. Handbook of self-regulation. Academic Press; San Diego: 2000. pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. Pathways to alcohol problems: A developmental account of the evidence for contextual contributions to risk. In: Zucker RA, Boyd GM, Howard J, editors. The development of alcohol problems. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 1994. pp. 255–289. [Google Scholar]