Abstract

Prion disease is characterized by the α→β structural conversion of the cellular prion protein (PrPC) into the misfolded and aggregated “scrapie” (PrPSc) isoform. It has been speculated that methionine (Met) oxidation in PrPC may have a special role in this process, but has not been detailed and assigned individually to the 9 Met residues of full-length, recombinant human PrPC [rhPrPC(23-231)]. To better understand this oxidative event in PrP aggregation, the extent of periodate-induced Met oxidation was monitored by electrospray ionization-MS and correlated with aggregation propensity. Also, the Met residues were replaced with isosteric and chemically stable, nonoxidizable analogs, i.e., with the more hydrophobic norleucine (Nle) and the highly hydrophilic methoxinine (Mox). The Nle-rhPrPC variant is an α-helix rich protein (like Met-rhPrPC) resistant to oxidation that lacks the in vitro aggregation properties of the parent protein. Conversely, the Mox-rhPrPC variant is a β-sheet rich protein that features strong proaggregation behavior. In contrast to the parent Met-rhPrPC, the Nle/Mox-containing variants are not sensitive to periodate-induced in vitro aggregation. The experimental results fully support a direct correlation of the α→β secondary structure conversion in rhPrPC with the conformational preferences of Met/Nle/Mox residues. Accordingly, sporadic prion and other neurodegenerative diseases, as well as various aging processes, might also be caused by oxidative stress leading to Met oxidation.

Keywords: conformational switch, expanded genetic code, methionine sulfoxide reductase, noncanonical analogs, unnatural amino acid sequence

The hallmark feature of conformational disorders such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, Huntington diseases, and transmissible spongiform encephalopathies is the ability of particular proteins to fold into stable alternative conformations (1). In most cases, this event results in protein aggregation and accumulation in tissues as fibrillar deposits (2). Prion diseases are caused by cerebral deposition of an aggregated pathological isoform of the cellular prion protein (PrPC) termed PrPSc (3), which is a membrane-bound glycoprotein found in the central nervous system of all mammals and avian species (4). Extensive structural studies (5) clearly revealed that, in PrPC, the C-terminal region (125–231) adopts an α-helical globular fold with a small 2-stranded β-sheet (Fig. 1B) (6), whereas the 100-membered N terminus is mainly unstructured (7). Despite high sequence conservation in all mammalian species, the specific function of the PrPC in healthy tissues still remains elusive (8).

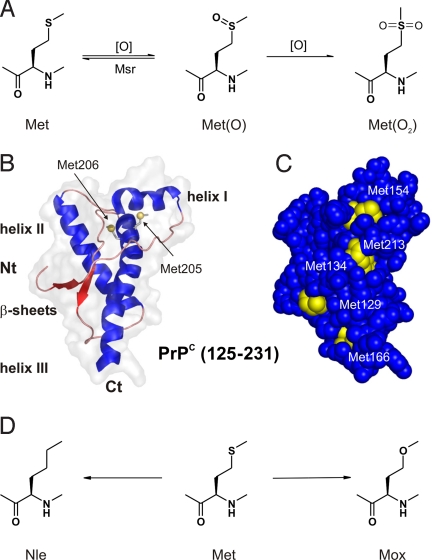

Fig. 1.

Methionine oxidation, PrPc structure, and chemical analogs. (A) Met oxidation to its (S)- and (R)-sulfoxide forms [Met(O)], which, in vivo, are catalytically reduced to Met by Met-sulfoxide reductase (MsrA and MsrB) (28); further oxidation of Met(O) leads irreversibly to the Met-sulfone [(Met(O2)]. (B) 3D structure of rhPrPC (125–231) (PDB accession no. 1QM0); and (C) surface representation of this folded part of PrP with Met residues highlighted in yellow. Except for Met-205/206, which are buried inside the PrPC structure, all other Met residues (including Met-109 and Met-112, which are part of the unstructured N-terminal domain) are solvent-exposed; therefore, in principle, susceptible to oxidation. (D) Met-analogs Nle and Mox used for replacement studies.

Prion diseases can be sporadic, inherited, and infectious (9). Whereas inherited diseases typically arise from mutations in the C-terminal domain, sporadic ones are the most common in humans (85%) (4), and can be assigned to the class of diseases arising from protein conformational disorders such as Alzheimer and Parkinson (10–12). Numerous studies unambiguously confirmed a causal role of protein misfolding in all these diseases (13). The infectious process is believed to be a self-propagating, autocatalytic conformational rearrangement, where recruited and misfolded PrPC catalyzes the conversion of further PrPC that further leads to the formation of β-sheet enriched fibrils (14). However, little is known about the initial event in this autocatalytic misfolding cascade. Beside genetic causes (mutations), various environmental factors such as molecular crowding, metal ions, chaperone proteins, membrane lipid composition, pH, and/or oxidative stress have been claimed as responsible (15, 16).

Whatever the origin, it is reasonable to assume that minor stochastically formed modifications of the polypeptide chain induce local α→β structural transition. In this context, methionine (Met) residues could represent the key structural switches because of their high sensitivity toward oxidation that converts the moderately hydrophobic thioether side chain into the hydrophilic sulfoxide form (Fig. 1A). Indeed, this redox-controlled Met↔Met(O) reaction can induce an α-helix↔β-sheet conformational switch in model peptides (17). Although Met is a rare amino acid in proteins (18), there are many important proteins whose activity is altered by Met-oxidation such as 1-antitrypsin calmodulin, fibronectin, cytochrome C, apolipoprotein, chymotrypsin, hemoglobin, etc. (reviewed in ref. 19).

However, proteins with higher numbers of surface-exposed Met residues might serve as a first defense against damage by reactive oxygen species (ROS) (20). The degree of oxidation of Met residues in cells is controlled by both, the balance of the production of ROS and the reduction of Met(O) back to Met by Met-sulfoxide reductases (Msr) (Fig. 1) (21). Also, diseases related to protein misfolding may be a consequence of an imbalance in cellular oxidation reaction and/or a loss of protective mechanisms (22). Thus, it is no surprise that the performance of related Msr enzymatic systems determines aging, stress resistance, and lifespan of bacteria, yeast, insects, and mammals (23).

A possible involvement of Met oxidation in the α→β conversion of PrPC has been proposed and susceptibility of the Met residues to oxidation in recombinant mouse and chicken PrPCs was reported (24). As expected, solvent-exposed Met residues of Syrian hamster PrPC were much more susceptible to oxidation than buried ones when using 3–10 mM H2O2 as oxidizing agent (25). However, CD measurements indicated only minor unfolding or aggregation under these conditions (25). Although MS allowed to detect some oxidized protein tryptic fragments of PrPSc, only controversial data are available, so far, about Met-oxidation in PrPSc forms, as well as in fibril formation (26, 27).

The Met residues in native PrPC are in the reduced (thioether) form, and the protein adopts a predominantly α-helical fold. We hypothesize that ROS-induced Met oxidation may well represent an initial event that leads to intramolecular α→β structural conversion followed by fatal PrPC→PrPSc transition and the autocatalytic misfolding cascade. However, in experimental studies of Met oxidation of PrPC, it is difficult to achieve controllable and selective side-chain oxidation. For this purpose, Met analogs with opposite conformational preferences, as applied in the present study, can provide a powerful tool to arrest different structural states of the Met-rich PrPC sequence. The incorporation of methoxinine (Mox) (Fig. 1D) in response to the AUG codon gives rise to an aggregation-prone β-sheet-rich structure most probably similar to that of Met(O)-rhPrPC. In contrast, norleucine (Nle) (Fig. 1D) in the rhPrPC sequence enhances hydrophobic interactions of the prion globular domain, making it resistant to oxidation and subsequent α→β intramolecular conversion. By this way, we were able to stabilize rhPrPC in a very predictive manner, as well as to alter rationally the global folding pattern of rhPrPC from a structure with predominantly α-helical to the structure with predominantly β-sheet content.

Results

Periodate-Induced Aggregation of Met-rhPrPC as Monitored by Cross-Correlation Spectroscopy.

The in vitro aggregation tendency of Met-rhPrPC was monitored using the well established de novo SDS-dependent in vitro aggregation assay (29, 30), based on confocal single molecule analysis with fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy (FCS) analysis (31, 32). In 0.2% SDS, rhPrPC exhibits a high α-helical content, and does not form aggregates. By diluting the SDS concentration to 0.0125%, a significant rise in cross-correlation amplitude indicates aggregation of rhPrPC.

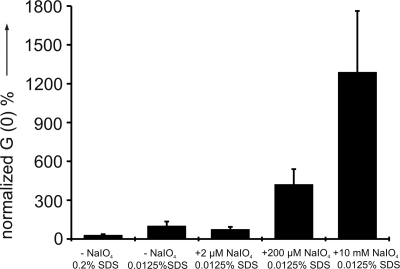

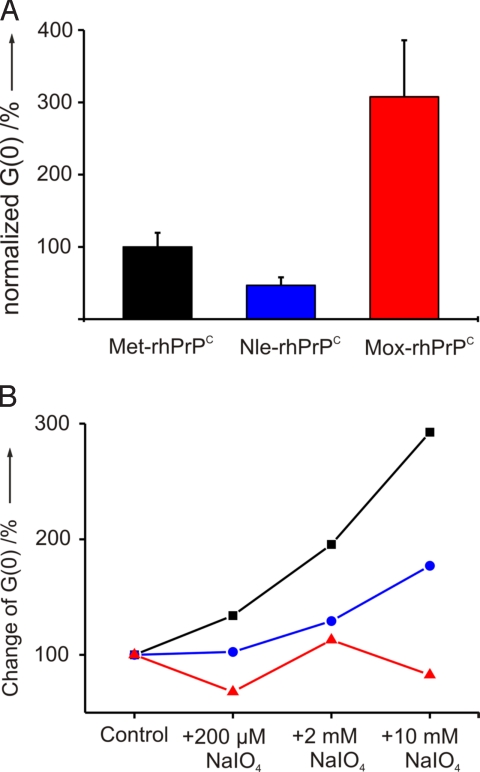

To study the effect of Met oxidation on the protein aggregation propensity, comparative aggregation assays were performed under different oxidative conditions. Peroxide H2O2 is routinely used in oxidation studies of many proteins including PrPCs from various organisms (25, 33). However, in our hands, sodium periodate proved to be the best oxidant to generate reliable and reproducible data. Each dilution of the protein was treated with a molar excess of sodium periodate (2 μM, 200 μM, and 10 mM; for more details, see SI Materials and Methods). The high excess of oxidant served to overcome the drastically reduced reaction rates at the low protein concentration necessary for FCS. As shown in Fig. 2, with an increase of the oxidant concentration a significantly enhanced aggregation of Met-rhPrPC can be observed.

Fig. 2.

Periodate-dependent aggregation of Met-rhPrPC determined by cross-correlation amplitude [G(0)]. Each data point represents the mean of 4 parallel samples.

Mapping Met Oxidation by MS.

The oxidation of Met-rhPrPC was performed at 0.4 mM concentration with 0.5, 5.0, and 25 eq of sodium periodate in 10 mM Mes, pH 6.0, on ice and 12 h, according to well established protocols (34). After tryptic digestion, the peptide mixture was analyzed by electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS. The 9 Met residues are distributed on 6 tryptic fragments, 2 of them with multiple Met residues. These are MMER (Met-205/206) and MAGAAAAGAVVGGLGGYMLGSAMSRPIIHFGSDYEDR (Met-112/129/134). Attempts to use Orbitrap MS for Met oxidation mapping in tryptic fragments of rhPrPC were reported recently (35). However, routine ESI-MS in the nanospray Orbitrap setup works in the presence of oxygen, which is a main source for unspecific oxidation of Met. To rule out unspecific Met oxidation by the analysis method, we used an ESI-MS setup that operates exclusively under nitrogen (Brucker Daltonics). Met- and Met(O)-peptide samples showed different retention times making semiquantitative estimations of the oxidation state possible.

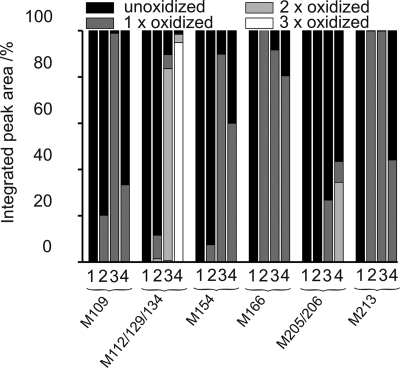

Expectedly, treatment with 0.5 eq of periodate did not induce detectable Met-oxidation, whereas a 10-fold increase of oxidant (5 eq) yielded almost quantitative oxidation of Met-213 (VVEQMCITQYER), and Met-166 (YPNQVYYRPMDEYSNQNNFVHDCVNITIK) (Figs. S1 and S2). The Met-112/129/134 peptide, Met-109 (TNMK), and Met-154 (ENMHR) exhibit rather low levels of modification, whereas no oxidation was observed for the Met-205/206 peptide (Fig. 3). Treatment of Met-rhPrPC with 25 eq of periodate resulted in partial precipitation. After centrifugation, both pellet and supernatant were analyzed. Approximately 30% of the Met-205/206 peptide in the soluble fraction contained only 1 Met(O), whereas in the remaining 70%, both Met-205 and Met-206 were not oxidized. The other tryptic fragments of the soluble fraction contained mainly Met(O) (Fig. S3). In both cases, CD spectra and melting curves of the oxidized proteins (5 and 25 eq per soluble fraction) were almost identical to those of the sample without periodate treatment (Fig. S2 and Fig. S4).

Fig. 3.

The extent of Met oxidation was evaluated from the integrated peak areas: (bar 1) without periodate, (bar 2) with 5 eq of periodate, (bar 3) with 25 eq of periodate (soluble fraction), and (bar 4) with 25 eq of periodate (pellet fraction).

In the pellet (with 25 eq of periodate), all thioether moieties of the tryptic fragment with Met-112/129/134 were fully oxidized. This peptide belongs to the unstructured N terminus. In the majority of the oxidized MMER (Met-205/206) fragment from the pellet showed both Met residues in the oxidized form (Fig. S5). However, a rather high proportion of this fragment contained intact Met residues; similarly, nonoxidized Met residues were additionally found at positions 109, 154, 166, and 213. Their presence in the pellet is most probably due to the pull-down effect caused by association of soluble protein molecules to insoluble aggregates. The overall pattern of the periodate-induced oxidation in all analyzed peptides is presented in Fig. 3.

These findings confirm that the buried Met-205/206 residues are less accessible to oxidants even when increasing the concentration to 25 eq. This fact agrees with previous reports from other laboratories (25, 33). With this optimized analytical method, rather confident quantification of the extent of oxidation of individual Met residues in rhPrPC by periodate was obtained.

Met Oxidation Studied by Met-Analogs.

To test the hypothesis that oxidation of the buried Met residues could be the critical event in vivo for the α→β structural transition in PrP, we attempted first to express rhPrPC with all Met residues fully replaced by Met(O) or even Met(O2) (Fig. 1A). Because these experiments failed, most probably due to the intracellular catalytic activity of Msr, the Met residues were replaced by chemically stable yet translationally active analogs that were meant to arrest the protein conformation in a defined state by mimicking native Met or Met(O). As best candidates the isosteric Met analogs Nle and Mox were selected (Fig. 1D), because these amino acids consist of nearly identical side-chain lengths, identical number of single rotating bonds, and are resistant to chemical oxidation. The polarities of the 2 noncanonical amino acids are extremely different. Compared with the moderately hydrophobic Met (water solubility, ≈360 mM), Nle is neutral and strongly hydrophobic (apolar) with a water solubility of ≈120 mM (36), whereas Mox [like Met(O)] is highly hydrophilic (polar) with a water solubility nearly equivalent to serine.

Expression and Isolation of Nle-rhPrPC and Mox-rhPrPC.

An almost quantitative incorporation of both Met analogs, Nle and Mox, into rhPrPC was achieved via routine bio-expression protocols, based on the supplementation incorporation (SPI) method (37). The purified proteins were analyzed by SDS/PAGE gel electrophoresis and Coomassie staining. Further analytical characterization was achieved by tryptic peptide fragment sequencing.

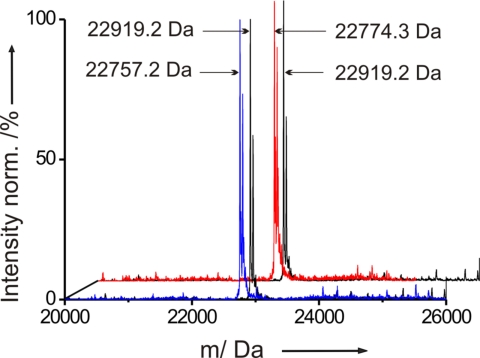

Mass Spectrometry.

The mass difference between Met-rhPrPC and its 2 variants suffices in both cases for analysis by ESI-MS. The mass found for Met-rhPrPC was 22,919.2 Da (Fig. 4), which is in excellent agreement with the theoretically expected value (22,919.19 Da). As observed with other systems (38), the substitution of the N-terminal Met in rhPrPC with Nle and Mox does not prevent their excision. The Met3Nle substitution lowers the molecular mass of the protein by 18 Da per Met residue. The expected and found mass for Nle-rhPrPC was 22,757.2 Da (Fig. 4). From the intensities of the mass ion signals, we could estimate semiquantitatively a high Nle incorporation (≈97%). Similarly, the molecular mass change from Met to Mox is 16 Da, which corresponds to a difference of 144 Da for the whole recombinant protein. Indeed, we found then an expected mass of 22,774.3 Da for Mox-rhPrPC (Fig. 4). However, the level of substitution was somewhat lower (≈85%) than for the Nle-variant.

Fig. 4.

Mass spectra of Met-rhPrPC (black), Nle-rhPrPC (blue), and Mox-rhPrPC (red). Accompanying peaks are most probably unspecifically bound Na+-adducts from buffer.

Pro- and Antiaggregation PrP Variants.

As shown in Fig. 5A, the aggregation capacity of Nle-rhPrPC is significantly reduced compared with that of Met-rhPrPC, under the identical experimental conditions. This strong antiaggregation effect directly correlates with an enhanced stability of the spatial structure and a high α-helical content of Nle-rhPrPC (see below). In contrast, the Met replacement by Mox in rhPrPC caused a strong proaggregatory effect. As expected, in the aggregation assay under oxidative conditions, the Nle- and Mox-variants were relatively insensitive to the different sodium periodate concentrations (Fig. 5B), and the observed steady increase has to be attributed to oxidative degradation of other sensitive residues, particularly Trp and Tyr (33). Thus, Nle-rhPrPC and Mox-rhPrPC proved to be suitable tools to investigate the effect of Met oxidation.

Fig. 5.

Aggregation properties. (A) In vitro aggregation of Met-rhPrPC compared with Nle-rhPrPC and Mox-rhPrPC in the absence of oxidants. (B) Aggregation tendency as a function of periodate concentration. The intrinsic aggregation tendency of all 3 samples in the absence of periodate is arbitrarily set to 100%. Data points represent the mean of 6 different measurements. Larger variations in Mox-rhPrPC (red triangles) sample are due to its extreme aggregation-propensity. See Materials and Methods for details (blue circles, Nle-rhPrPC; black squares, Met-rhPrPC).

Conformational Properties of Nle-rhPrPC and Mox-rhPrPC.

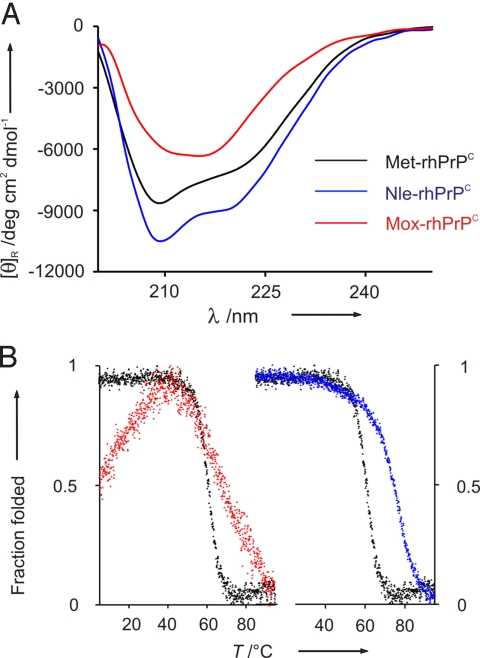

The far-UV CD spectrum of Met-rhPrPC at 37 °C in 10 mM Mes at pH 6.0 is identical to those previously reported (33, 39), and has the 2 negative maxima at 222 and 208 nm, typical for largely α-helical proteins. Compared with the parent Met protein, the spectrum of the Nle-variant (Fig. 6A) shows increased intensities of the 2 maxima by ≈10%, indicating further stabilization of the native state. Conversely, for the Mox-rhPrPC, significant changes in the dichroic properties were observed. The negative maximum is shifted to 215 nm, and the overall intensity is markedly reduced. Obviously, the global Met→Mox replacement in the PrP leads to conversion of the prevalent α-helical structure to β-type conformations. All 3 spectra were also monitored in the presence of 0.2% SDS, which is known to prevent aggregation in rhPrPC (30). Expectedly, no changes in dichroic signals were observed, confirming the absence of sample aggregation.

Fig. 6.

Secondary structure analysis and thermal denaturation. (A) CD spectra of Met-rhPrPC and its Nle- and Mox-variants at 37 °C and 0.2 mg/mL in 10 mM Mes at pH 6.0. (B) Thermal denaturation monitored by the changes of dichroic intensities at 222 nm in function of temperature.

The temperature-induced unfolding of Met-, Nle-, and Mox-rhPrPC was monitored by recording the dichroic intensities at 222 nm (Fig. 6B). Because thermal unfolding of these proteins leads to irreversible denaturation, thermodynamic parameters could not be derived. As already suggested by the increased dichroic intensities at 37 °C, the enhanced stability of Nle-rhPrPC is well reflected by the higher melting point (Tm = 74.4 ± 3.4 °C) compared with Met-rhPrPC (Tm = 65.2 ± 4.2 °C) (Fig. 6B). An enhanced thermal stability induced by the Met→Nle replacement has previously been observed for the α-helical annexin A5 (36), and has been attributed to the increased hydrophobicity of the protein core by the buried Nle residues. Similarly, the buried Nle 205/206 should strongly contribute to the markedly enhanced stability of the Nle-rhPrPC variant.

For the thermal unfolding of Mox-rhPrPC, a gradual, noncooperative melting between 42 and 95 °C was observed. Such unfolding patterns are generally typical for proteins that either are very flexible and partially unfolded in the ground state or contain heterogeneous populations of folded states. We attribute the different unfolding behavior of Mox-rhPrPC as compared with Met- or Nle-rhPrPC to its flexibility and the mixed populations of prevalently β-sheet structure of this variant.

An additional striking feature of the temperature-induced denaturation experiment with the Mox-variant is the maximum stability in the temperature range between 35 and 45 °C, whereas below and above these temperatures, protein denaturation takes place (Fig. 6B). A decrease in protein stability induced by lower temperatures is known as cold denaturation (40). In natural proteins, cold denaturation usually occurs below the freezing point of water, and was observed for proteins with hydrophilic amino acid residues in the core structure (41). Therefore, the cold-denaturation-like melting of Mox-rhPrPC is most probably caused by the introduction of hydrophilicity in the globular domain of rhPrPC with the Mox 205/206 residues. A similar observation was reported recently for a variant of the ribonuclease inhibitor bastar containing a hydrophilic tryptophan derivative in the protein interior (42).

Discussion

In this study, we focused on a better understanding of how the intramolecular α→β structural conversion of the cellular PrP may be related to the chemistry of the Met side chains. The formation of PrPSc from PrPC is a posttranslational process that is believed to follow an autocatalytic mechanism (14). A chemical modification of particular residues might trigger this misfolding cascade. In fribrillar PrPSc, such initial chemical modification may be difficult to detect, because a small seed of modified molecules may suffice for the onset of the process. No candidate for chemical modification could be unambiguously identified. Although there is increasing evidence for an important role of PrPC in oxidative stress (15), so far, a direct correlation between PrPC oxidation and its conversion to a β-sheet rich form was not clearly established.

Oxidation of Met Residues in rhPrPC and α→β Structural Conversion.

In nature, the PrPC is an N-linked glycoprotein normally bound to the neuronal cell membrane by a GPI anchor (4). However, unglycosylated isoforms of PrPC exist as well in vivo and their conversion to PrPSc is confirmed (43). Also, Hornemann et al. (44) demonstrated by circular dichroism and 1H-NMR spectroscopy that the 3D structure and the thermal stability of the natural glycoprotein, as well as the recombinant polypeptide, are essentially identical. A number of recent experimental and theoretical studies investigated the possible role of glycosylation and membrane anchoring on PrPC structure. Elfrink et al. (45) found that membrane anchoring of PrP at high concentration profoundly alters its secondary structure, whereas DeMarco and Deggett (46) reported that glycosylation and attachment of PrPC to the membrane surface via a GPI anchor does not significantly change the structure or dynamics of PrPC. Independently of this unresolved issue, it is unlikely that the state of the protein in solution or in the membrane-anchored form has an influence on the structural perturbation caused by the oxidation of Met residues localized in the folded, exposed part of the protein.

Most of its 9 Met residues are surface-exposed and located in the structured globular part (125–231) as follows: Met-129 in the β-strand I, Met-134 in the loop between β-strand 1 and α-helix I, Met-154 in α-helix I, and Met-166 in β-strand II. Only Met-109 and Met-112 are located in the unstructured N terminus (23–124). However, Met-205 and Met-206 in α-helix III are buried, whereas Met-213 is only partially surface-exposed (Fig. 1).

The position 205 is invariantly occupied by hydrophobic residues in PrPs from different species, and is well conserved in all mammalian species. Met-205 is part of the hydrophobic face of helix III, and is involved in a network of interactions that stabilize the packing of this structural motif. Its replacement by hydrophilic Ser or Arg prevents folding in vivo of the mutant protein (47), a fact that was confirmed by molecular dynamic simulations (48). A similar structural role can possibly be assigned to the vicinal Met-206 residue. Indeed, by using molecular dynamics simulations, Colombo et al. (49) suggested recently that oxidation of helix III Met residues (Met-206 and Met-213) might be the switch for triggering the initial α-fold destabilization required for the productive pathogenic conversion of PrP. Therefore, the oxidation of PrPC, especially the Met-205/206 in the hydrophobic core, could dramatically change the intrinsic local conformational preferences, and facilitate global α→β structural conversion in PrP.

Our oxidation experiments accord with this hypothesis. We could not only observe an increase in the aggregation tendency of rhPrPC on increasing the oxidant concentration (Fig. 2), but also detect a higher proportion of oxidized Met residues in this procedure. Although at lower oxidant concentration mainly the surface-exposed Met residues are oxidized to Met(O), with 25 eq of sodium periodate even the buried Met-205/206 residues are at least partially oxidized, as well assessed by the ESI-MS analysis of tryptic digests (Fig. 3). Although the oxidation of these critical residues provokes precipitation, probably as a result of enhanced aggregation, a quantitative correlation between oxidation state of the Met residues and aggregation propensity of rhPrPC is prevented by the experimentally different conditions required for the aggregation assay (i.e., the very low protein concentration and, thus, strongly reduced reaction rates that require higher oxidant excesses). Nevertheless, by increasing the periodate amounts a significantly enhanced aggregation, propensity was observed (Fig. 5B). A contribution of oxidative degradation of sensitive residues such as His, Trp, and Tyr cannot be excluded as suggested by other studies (25, 33). However, the main effect has to result from the conversion of less accessible Met residues to the Met(O) form as the Nle-variant, which lacks these Met residues, shows only a slight increase in the aggregation tendency under comparative oxidative conditions.

Chemical Model for α→β Conversion in rhPrPC.

In the current study, we sought to delineate how the intramolecular α→β structural conversion of rhPrPC could take place in the frame of a well-defined model system. To create such a model system that allows a direct correlation between Met oxidation and aggregation propensity, we first aimed at the quantitative substitution of Met by Met(O) in the PrP. Unfortunately, our attempts to replace all Met residues in rhPrPC with Met(O) by the SPI method failed. Therefore, we selected the alternative approach of replacing the Met residues with synthetic Met analogs. They offer a good chemical model, because they are (i) insensitive to oxidation, (ii) no substrates for intracellular Met-sulfoxide reductases, and (iii) their effect on conformational preferences can be derived from model studies. Accordingly, the Met residues were replaced by the significantly more hydrophilic isosteric Mox to mimic the Met(O)-rhPrPC form and combined with the expression of the oxidation-insensitive Nle-variant (Fig. 4).

From peptide studies, Met is well known to stabilize and efficiently induce α-helical conformations (50, 51). Similarly, Nle exhibits an even higher intrinsic preference for α-helical states, but lower preferences for β-sheet conformations than Met residues (52). In the absence of experimental data on structural propensities of Mox residues, which conceivably could prefer β-sheet over α-helical conformation because of their hydrophilicity, we have addressed this question with the suitable model peptide YLKAMLEAMAKLMAKLMA-NH2 of Dado and Gellman (17), which showed an α→β transition on Met-oxidation. The Nle-peptide exhibits the typical α-helical CD profile with a very high content of ordered structure (>80% α-helix). Conversely, the related Mox-peptide shows a dramatically decreased α-helical content (≈40%) with a 6-fold increase in random coil, but also a significant percentage of β-type structure (20%) (Fig. S6 and Table S1). These results are in agreement with observations made with Met-containing peptides, which are related to the α-helices of apolipoprotein A-I, where Met oxidation produced significantly reduced helical fold (53). Together, one can conclude that Mox represents a good mimic for Met(O).

The findings from model peptides are reflected at the level of the rhPrPC variants, with the Nle-variant exhibiting a further stabilized α-helical core (Fig. 6) with low tendency to aggregation. Conversely, the CD spectrum of the Mox-variant suggests a largely β-structured fold with high aggregation propensity. By this way, a reliable model was provided, which clearly evidences how the hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity interplay is crucial to the α→β conversion in rhPrPC structure. This experimental model supports a natural scenario where oxidative conversion of Met residues, especially buried ones, into Met(O) may act as primary event in sporadic prion disease induction, particularly taking into account the pronounced structural ambivalence of PrPC. In fact, model studies on the peptides related to α-helix II of PrPC clearly revealed a surprisingly low free energy difference between the α-helical and β-sheet conformations of only 5–8 kJ·mol−1, confirming at least for this helix a conformational ambivalence (54, 55).

Perspectives.

The residue-specific incorporation of Nle and Mox in full-length rhPrPC (23–231) provided a useful chemical model to study the role of Met residues in prion α→β structural conversion. An excellent correlation between solution properties of Met/Nle/Mox side chains and the conformational states of the related protein variants enabled us to anticipate Met-oxidation as an initial destabilizing event of the rhPrPC α-fold, and its subsequent transition and assembly into PrPSc. Therefore, by expanding the genetic code of the AUG triplet with Nle and Mox, it is possible to arrest physiologically and pathologically relevant conformational states of the PrP. These extreme conformational states are usually not amenable in animal models nor with peptide fragments. Our experimental approach allows delineating and understanding the nature of structural transitions underlying those fundamental biological processes that are crucial in protein misfolding diseases. We envision the use of this methodology for studies of other proteins highly relevant for neurodegenerative, as well as other aging-related diseases.

Materials and Methods

Quantification of Individual Met Residue Oxidation in rhPrPC on Periodate Addition.

The oxidation of Met-rhPrPC was performed at 0.4 mM protein concentration with 0.5, 5, and 25 eq of sodium periodate in 10 mM Mes, pH 6.0, at 0 °C and overnight, according to well established protocols (34). After tryptic digestion, the peptide mixture was analyzed by ESI-MS. Samples were separated by Symmetry Varian Pursuit XRs ultra C18 column (Varian) with a flow rate of 250 μL/min, and 80-min linear gradient from 30- 90% acetonitrile/0.05% trifluoroacetic acid.

Other Experimental Procedures.

Detailed description of all other experimental procedures is provided in SI Materials and Methods. Also, all ESI-MS analyses of oxidized and unoxidized trypsinized fragments are available from authors on request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. Stefan Uebel und Ms. Elisabeth Wayher for excellent assistance in analytical and instrumental analyses, Uwe Bertsch (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich) for providing recombinant PrP and help at the initial phase of the project, and Dr. Birgit Wiltschi for critical reading of our manuscript. This work was supported by the BioFuture Program of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany and the Munich Center for Integrated Protein Sciences.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0902688106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Soto C, Estrada LD. Protein misfolding and neurodegeneration. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:184–189. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiti F, Dobson CM. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:333–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolton DC, McKinley MP, Prusiner SB. Identification of a protein that purifies with the scrapie prion. Science. 1982;218:1309–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.6815801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prusiner SB. Prion diseases and the bse crisis. Science. 1997;278:245–251. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lysek DA, et al. Prion protein nmr structures of cats, dogs, pigs, and sheep. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:640–645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408937102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riek R, et al. Nmr structure of the mouse prion protein domain prp(121–231) Nature. 1996;382:180–182. doi: 10.1038/382180a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donne DG, et al. Structure of the recombinant full-length hamster prion protein prp(29–231): The n terminus is highly flexible. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13452–13457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissmann C. The state of the prion. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:861–871. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prusiner SB. Molecular-biology of prion diseases. Science. 1991;252:1515–1522. doi: 10.1126/science.1675487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mrak RE, Griffin WST, Graham DI. Aging-associated changes in human brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:1269–1275. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199712000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin JB. Molecular basis of the neurodegenerative disorders. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1970–1980. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906243402507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnham KJ, Cappai R, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Hill AF. Delineating common molecular mechanisms in alzheimer's and prion diseases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy J, Gwinn-Hardy K. Genetic classification of primary neurodegenerative disease. Science. 1998;282:1075–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bieschke J, et al. Autocatalytic self-propagation of misfolded prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12207–12211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404650101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milhavet O, et al. Prion infection impairs the cellular response to oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13937–13942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250289197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeMarco ML, Daggett V. Local environmental effects on the structure of the prion protein. C R Biol. 2005;328:847–862. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dado GP, Gellman SH. Redox control of secondary structure in a designed peptide. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:12609–12610. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dayhoff MO, Barker WC, Hunt LT. Establishing homologies in protein sequences. Methods Enzymol. 1983;91:524–545. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)91049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine RL, Moskovitz J, Stadtman ER. Oxidation of methionine in proteins: Roles in antioxidant defense and cellular regulation. IUBMB Life. 2000;50:301–307. doi: 10.1080/713803735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies MJ. The oxidative environment and protein damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1703:93–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moskovitz J, Bar-Noy S, Williams WM, Berlett BS, Stadtman ER. Methionine sulfoxide reductase (msra) is a regulator of antioxidant defense and lifespan in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12920–12925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231472998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine RL, Berlett BS, Moskovitz J, Mosoni L, Stadtman ER. Methionine residues may protect proteins from critical oxidative damage. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999;107:323–332. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petropoulos I, Friguet B. Maintenance of proteins and aging: The role of oxidized protein repair. Free Radical Res. 2006;40:1269–1276. doi: 10.1080/10715760600917144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong BS, Wang H, Brown DR, Jones IM. Selective oxidation of methionine residues in prion proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;259:352–355. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Requena JR, et al. Oxidation of methionine residues in the prion protein by hydrogen peroxide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;432:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breydo L, et al. Methionine oxidation interferes with conversion of the prion protein into the fibrillar proteinase k-resistant conformation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15534–15543. doi: 10.1021/bi051369+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baskakov IV, Breydo L. Converting the prion protein: What makes the protein infectious. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:692–703. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moskovitz J, Weissbach H, Brot N. Cloning and expression of a mammalian gene involved in the reduction of methionine sulfoxide residues in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2095–2099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Post K, et al. Rapid acquisition of beta-sheet structure in the prion protein prior to multimer formation. Biol Chem. 1998;379:1307–1317. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.11.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giese A, Levin J, Bertsch U, Kretzschmar H. Effect of metal ions on de novo aggregation of full-length prion protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:1240–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwille P, MeyerAlmes FJ, Rigler R. Dual-color fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy for multicomponent diffusional analysis in solution. Biophys J. 1997;72:1878–1886. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78833-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bieschke J, et al. Ultrasensitive detection of pathological prion protein aggregates by dual-color scanning for intensely fluorescent targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5468–5473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Redecke L, et al. Structural characterization of beta-sheeted oligomers formed on the pathway of oxidative prion protein aggregation in vitro. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knowles JR. Role of methionine in alpha-chymotrypsin-catalysed reactions. Biochem J. 1965;95:180–190. doi: 10.1042/bj0950180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canello T, et al. Methionine sulfoxides on prpsc: A prion-specific covalent signature. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8866–8873. doi: 10.1021/bi800801f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Budisa N, et al. Atomic mutations in annexin v - thermodynamic studies of isomorphous protein variants. Eur J Biochem. 1998;253:1–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2530001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Budisa N. Prolegomena to future efforts on genetic code engineering by expanding its amino acid repertoire. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:3387–3428. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiltschi B, Merkel L, Budisa N. Fine tuning the n-terminal residue excision with methionine analogues. Chembiochem. 2009;10:217–220. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan KM, et al. Conversion of alpha-helices into beta-sheets features in the formation of the scrapie prion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10962–10966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Privalov PL. Cold denaturation of proteins. Biophys J. 1990;57:A26–A26. doi: 10.3109/10409239009090612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blandamer MJ, Briggs B, Burgess J, Cullis PM. Thermodynamic model for isobaric heat-capacities associated with cold and warm thermal-denaturation of proteins. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans. 1990;86:1437–1441. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubini M, Lepthien S, Golbik R, Budisa N. Aminotryptophan-containing barstar: Structure-function tradeoff in protein design and engineering with an expanded genetic code. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1764:1147–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parchi P, et al. Typing prion isoforms. Nature. 1997;386:232–233. doi: 10.1038/386232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hornemann S, Schorn C, Wuthrich K. Nmr structure of the bovine prion protein isolated from healthy calf brains. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:1159–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elfrink K, et al. Structural changes of membrane-anchored native prpc. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10815–10819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804721105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeMarco ML, Daggett V. Characterization of cell-surface prion protein relative to its recombinant analogue: Insights from molecular dynamics simulations of diglycosylated, membrane-bound human prion protein. J Neurochem. 2009;109:60–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05892.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winklhofer KF, et al. Determinants of the in vivo folding of the prion protein - a bipartite function of helix 1 in folding and aggregation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14961–14970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirschberger T, et al. Structural instability of the prion protein upon m205s/r mutations revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys J. 2006;90:3908–3918. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.075341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colombo G, Meli M, Morra G, Gabizon R, Gasset M. Methionine sulfoxides on prion protein helix-3 switch on the α-fold destabilization required for conversion. PlosONE. 2009;4:e4269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Creamer TP, Rose GD. Alpha-helix-forming propensities in peptides and proteins. Proteins. 1994;19:85–97. doi: 10.1002/prot.340190202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Minor DL, Kim PS. Measurement of the beta-sheet-forming propensities of amino-acids. Nature. 1994;367:660–663. doi: 10.1038/367660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lyu PC, Sherman JC, Chen A, Kallenbach NR. Alpha-helix stabilization by natural and unnatural amino-acids with alkyl side-chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5317–5320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anantharamaiah GM, et al. Effect of oxidation on the properties apolipoproteins a4 and a4. J Lipid Res. 1988;29:309–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tizzano B, et al. The human prion protein alpha2 helix: A thermodynamic study of its conformational preferences. Proteins. 2005;59:72–79. doi: 10.1002/prot.20395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ronga L, et al. Structural characterization of a neurotoxic threonine-rich peptide corresponding to the human prion protein alpha2-helical 180–195 segment, and comparison with full-length alpha2-helix-derived peptides. J Pept Sci. 2008;14:1096–1102. doi: 10.1002/psc.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.