Abstract

Global warming is causing ocean warming and acidification. The distribution of Heliocidaris erythrogramma coincides with the eastern Australia climate change hot spot, where disproportionate warming makes marine biota particularly vulnerable to climate change. In keeping with near-future climate change scenarios, we determined the interactive effects of warming and acidification on fertilization and development of this echinoid. Experimental treatments (20–26°C, pH 7.6–8.2) were tested in all combinations for the ‘business-as-usual’ scenario, with 20°C/pH 8.2 being ambient. Percentage of fertilization was high (>89%) across all treatments. There was no difference in percentage of normal development in any pH treatment. In elevated temperature conditions, +4°C reduced cleavage by 40 per cent and +6°C by a further 20 per cent. Normal gastrulation fell below 4 per cent at +6°C. At 26°C, development was impaired. As the first study of interactive effects of temperature and pH on sea urchin development, we confirm the thermotolerance and pH resilience of fertilization and embryogenesis within predicted climate change scenarios, with negative effects at upper limits of ocean warming. Our findings place single stressor studies in context and emphasize the need for experiments that address ocean warming and acidification concurrently. Although ocean acidification research has focused on impaired calcification, embryos may not reach the skeletogenic stage in a warm ocean.

Keywords: climate change, ocean warming, ocean acidification, sea urchin fertilization and development, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, scenarios

1. Introduction

Global warming and increased atmospheric CO2 are causing the oceans to become warmer and acidify (Feely et al. 2004; IPCC 2007), the latter through the absorption of CO2, which dissolves in sea water to form carbonic acid. This acid dissociates into protons and bicarbonate ions, thereby decreasing pH. Atmospheric CO2 concentration will increase from present levels (approx. 300–380 ppm) to 450–1000 ppm by 2100, with a corresponding predicted decrease in ocean pH by 0.14–0.35 units, assuming the IPCC ‘business-as-usual’ scenario (Caldeira & Wickett 2003; Feely et al. 2004; IPCC 2007; Fabry et al. 2008).

Our understanding of the potential impacts of increased temperature and acidification on marine biota is impeded by the scarcity of empirical data and a focus on single stressor studies, many of which use stressor levels beyond values predicted by climate change models (for reviews, see Poloczanska et al. 2007; Fabry et al. 2008; Przeslawski et al. 2008). In addition, research emphasis has been directed to coral calcification (Reynaud et al. 2003; Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2007), with few data on the diverse non-coral benthic invertebrates (Przeslawski et al. 2008). In reality, the oceans will warm and acidify at the same time with the extent of warming varying among regions. We have a poor understanding of the biological consequences of the interactive effects of warming and acidification.

Eastern Australia is projected to be a climate change hot spot, where, owing to a disproportionate increase in sea surface temperature (SST), marine life in the region is anticipated to be particularly vulnerable to impacts of climate change and other stressors (CSIRO Climate System Model Mk3.5; see Poloczanska et al. 2007). In this region, SST has risen 2.3°C since the 1940s, with a further rise of 2–3°C predicted as early as 2070. The distribution of the sea urchin Heliocidaris erythrogramma, an ecologically important member of the shallow-water marine biota of temperate Australia, coincides with this hot spot (Laegdsgaard et al. 1991). Here, we determined the temperature and pH/pCO2 range at which fertilization and normal embryonic development occurs in H. erythrogramma within predicted values for 2070–2100 (SST: +2–4°C, pH −0.14 to 0.35 units) and beyond (SST: +6°C, pH −0.6 units) in simultaneous exposure to both stressors. During the spawning season, H. erythrogramma gametes and embryos currently experience SST of approximately 19–24°C and pH 8.1–8.3 (Newell 1961; Laegdsgaard et al. 1991). Our experimental treatments ranged from 20 to 26°C and pH 7.6 to 8.2, with the 26°C/pH 7.6 treatment being beyond the most extreme predicted for 2070–2100 (IPCC 2007; but see Whooten et al. 2008). Although recent focus on ocean acidification has been on biocalcification (Reynaud et al. 2003; Feely et al. 2004; Fine & Tchernov 2007; Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2007; Wood et al. 2008), it is essential to determine whether benthic calcifiers will be able to reach the skeletogenic developmental stage.

Sea water with high pCO2 and reduced pH has negative impacts on growth, reproduction and development of marine invertebrates due to direct pH effects and hypercapnia (Kurihara & Shirayama 2004; Michaelidis et al. 2005; Pörtner et al. 2005; Wood et al. 2008). Increased temperature has a direct impact on physiological function, increasing growth and developmental rates (Fujisawa & Shigei 1990; Palmer 1994; Reynaud et al. 2003; O'Connor et al. 2007). In a long history of research, numerous studies provide data on the influence of temperature or pH on echinoderm fertilization and development (e.g. Farmanfarmaian & Giese 1963; Chen & Chen 1992; Bay et al. 1993; Roller & Stickle 1993; Riveros et al. 1996; Kurihara & Shirayama 2004; Carr et al. 2006; Dupont et al. 2008; Havenhand et al. 2008), but there are no published data on the potential interactive effects of increased temperature and acidification. These data, within a range applicable to climate change scenarios, are crucial to understand the potential impact of climate change on basic biological processes essential for the integrity and persistence of all marine populations. We assessed the potential interactive impacts of ocean warming and acidification on the early life-history stage of a free spawning benthic invertebrate to enable predictions as to how marine biota may fare with respect to climate change.

2. Material and methods

(a) Study organism and exposure to stressors

Heliocidaris erythrogramma were collected near Sydney, Australia and induced to spawn by injection of 1–2 ml of 0.5 M KCl. Experiments used gametes from at least two males and two females. Gametes were collected directly from the aboral surface using glass pipettes. The eggs were placed in filtered sea water (FSW; 0.2 μm) and sperm were collected dry. All experiments were conducted with freshly collected FSW, salinity 36 ppt, pH 8.25 (s.e.=0.02, n=5) and dissolved oxygen (DO)≥85 per cent. Sea-water variables (pH, DO, temperature) were measured using a WTW Multiline F/Set-3 multimeter. Total alkalinity (TA) was determined for each sea-water source (Sydney Water Monitoring Services). Experimental pCO2 values were determined from TA, pH and salinity data using the CO2 system calculation program (Lewis & Wallace 1998). Treatments (20, 24 and 26°C; pH 7.6, 7.8, 7.9 and 8.2; range pCO2=230–690 ppm) were tested in all combinations for the 2070–2100 ‘business-as-usual’ scenario and beyond (IPCC 2007). Temperature imprinting of reproduction and development plays a major role in echinoid developmental tolerance (O'Conner & Mulley 1977; Fujisawa & Shigei 1990) and the 20°C control reflected the recent thermal history of the adults. Experimental temperatures, 24 and 26°C, were +4–6°C above ambient. A rangefinder study determined that temperatures≥28°C are lethal to H. erythrogramma embryos (H. D. Nguyen 2007, unpublished data). The experimental pH 7.6, 7.8 and 7.9 (approx. 0.3–0.6 pH units below ambient) were achieved by bubbling CO2 gas into the water until the desired pH was reached. DO levels were maintained by the simultaneous bubbling of air in all water used.

(b) Fertilization

The total number of eggs for each experiment was measured from a 50 ml suspension determined through counts of 100 μl aliquots. For each experiment, the eggs were split into 12 beakers (500 ml) at three temperatures and four pH levels at densities of 3–4 eggs ml−1. The eggs were preincubated in experimental water for 20 min prior to fertilization. Water baths were used to maintain constant temperature. The sperm concentration was used, 103 sperm ml−1, as determined by haemocytometer counts. These conditions resulted in more than or equal to 90 per cent fertilization and high rates of normal development (≥75%) in procedural controls.

Just prior to fertilization, the sperm were placed in the experimental water for a few seconds at the concentration required to ensure appropriate fertilization conditions when added to the beakers containing eggs. After 15 min, the eggs were rinsed three times in experimental FSW to remove excess sperm and resuspended in fresh experimental FSW. Fertilization success was determined after 2 h as the proportion of eggs that had a fertilization envelope or exhibited cleavage, out of three samples of 50 eggs taken from the egg suspension. Five independent fertilizations were undertaken with full replication for each treatment.

(c) Development

Fertilized eggs were separated into replicate beakers (100 ml) containing experimental water at densities of approximately 3–4 eggs ml−1. For each independent fertilization, 72 beakers (three temperatures×four pH, two sampling times×three replicate beakers per sampling time) containing approximately equal numbers of embryos were reared in the same conditions used for fertilization. The beakers were covered with parafilm to minimize evaporation. At two time points (2–3 h cleavage and 19–20 h gastrulae), three beakers were removed from each treatment and the percentage of normal development was determined in the first 50 embryos collected from the beakers. The beakers were discarded after scoring. Experimental water was renewed 4–5 h post-fertilization and the beakers were incubated for 15–16 h overnight. H. erythrogramma is routinely reared at 20–24°C (Kobayashi 1980; Byrne et al. 2001), with the latter being the maximum summer SST. Sea-water pH in the treatments measured at 4–5 h did not change and pH data from the end of the experiment (19–20 h) is provided in table 1. Embryos from 20°C/pH 8.2 fertilizations were reared to the rudiment stage (4 days) to assess the quality of all embryo sources.

Table 1.

Mean pH in treatments at the end (20 h) of the five experiments. Value in parentheses is the standard error.

| temperature (°C) | pH 7.9 | pH 7.8 | pH 7.6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 8.06 (0.23) | 7.85 (0.1) | 7.67 (0.02) |

| 24 | 7.96 (0.01) | 7.87 (0.02) | 7.77 (0.02) |

| 26 | 8.05 (0.04) | 7.89 (0.04) | 7.88 (0.07) |

(d) Statistical analyses

All dependent variables (fertilization, cleavage and gastrulae) were analysed by two-way ANOVA with temperature and pH as fixed factors. The three beakers within runs were used to improve the precision of our estimates and means values were used as replicates in each experiment (n=5). All percentage data were arcsine transformed prior to ANOVA and assumptions of the analysis were checked before proceeding. Normality was assessed visually and Cochran's test was used to ensure that the variances were homogeneous. Where significant differences were evident, the Newman–Keuls (NK) multiple comparison test was used for post hoc analyses. Data analyses were run on SPSS.

3. Effects of ocean warming and acidification on fertilization in H. erythrogramma

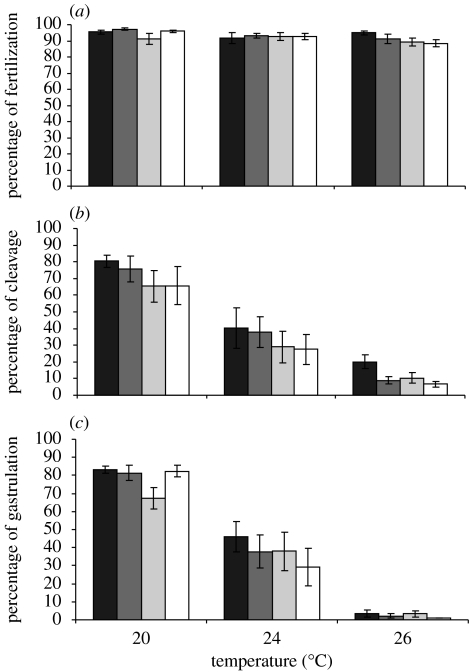

Percentage of fertilization was high (>89%) across all treatments with a slight decrease at upper warming (figure 1a), and this difference was significant (temperature F2,48=3.52, p=<0.05) with no effect of pH (pH F3,48=1.40, p=0.25). There was no interaction between temperature and pH (F6,48=0.86, p=0.53). Multiple comparison analyses revealed that fertilization did not differ between the 20 and 24°C nor between the 24 and 26°C treatments, but did differ between the 20 and 26°C treatments. Thus, at the upper warming (+6°C) and pCO2 acidification (pH −0.6 units) scenarios, fertilization of H. erythrogramma was affected slightly by temperature but not pH.

Figure 1.

Effect of temperature and pH on the percentage of (a) fertilization, (b) normal cleaving embryos and (c) normal gastrulae of H. erythrogramma. The 20°C and pH 8.2 treatment represented ambient conditions. Black bars, 8.2; dark grey bars, 7.9; light grey bars, 7.8; white bars, 7.6.

4. Effects of ocean warming and acidification on the development of H. erythrogramma

Following fertilization in experimental conditions, temperature had a significant effect on the development of H. erythrogramma, but pH did not (cleavage: temperature F2,48=58.05, p<0.0001, pH F3,48=1.63, p=0.19; gastrulation: temperature F2,48=155.89, p<0.0001, pH F3,48=1.23, p=0.31; figure 1b,c). The percentage of normal cleaving embryos 2–3 h post-fertilization was significantly lower as temperature increased (NK 20>24>26°C), as was the percentage of normal gastrulae 24–26 h post-fertilization (NK 20>24>26°C; figure 1b,c). Hence, at the highest temperature (26°C), the percentage of embryos showing normal cleavage fell below 20 per cent and gastrulation fell to <4 per cent, while, at 20°C, the percentage developing normally was more than 65 per cent across all pH levels. Thus, temperature had a significant effect on developmental failure at the upper warming (+4–6°C) level, regardless of pH. In addition, there was no significant interaction between these factors (cleavage: F6,48=0.13, p=0.99; gastrulation: F6,48=1.17, p=0.34). Control embryos reared for 4 days at 20°C/pH 8.2 produced a mean of 75 per cent (s.e.=5, n=5) rudiment stage larvae.

5. Discussion

Temperature, as the single most important environmental factor controlling marine populations, has long been the focus of physiology, phenology, biogeography and life-history biology studies (Vernberg 1962; O'Conner & Mulley 1977; Pechenik 1987; Olive 1995), with recent interest in the influence of temperature change on range extensions and contractions (Hays et al. 2005; O'Connor et al. 2007; Visser 2007; Przeslawski et al. 2008).

As we report here for H. erythrogramma, single stressor studies of thermotolerance in a diverse suite of tropical and temperate sea urchins show that fertilization and early development are robust to temperatures well above ambient and the increases expected from climate change (Farmanfarmaian & Giese 1963; Chen & Chen 1992; Roller & Stickle 1993). Thermotolerance in sea urchin fertilization and early development is conveyed by maternal factors imprinted by ovary temperature (Fujisawa 1995; Yamada & Mihashi 1998) and potentially include protective heat shock proteins (Sconzo et al. 1997). There is strong evidence that adult thermal history, particularly maternal acclimatization, influences thermal tolerance in echinoderm fertilization and development due to adaptive phenotypic plasticity with respect to prevailing temperatures (O'Conner & Mulley 1977; Fujisawa 1989, 1995; Johnson & Babcock 1994; Bingham et al. 1997). Our experiments show that fertilization using gametes from H. erythrogramma adults acclimatized at 20°C was thermotolerant to 26°C (+6°C above ambient SST). In development, this tolerance was reduced to 24°C (+4°C above ambient SST), with developmental failure at 26°C, regardless of pH. Developmental arrest in the 26°C/pH 8.2 treatment in hatched embryos followed transcription of the hatching enzyme, a zygotic genome product, indicating that arrested development occurred after switching on of the zygotic genome and depletion of protective maternal factors. This developmental threshold (+4°C) falls within the maximum environmental warming predicted for eastern Australia by 2070–2100 and also coincides with the maximum SST (24°C) that spawned gametes and dispersive embryos experience in a warm summer. It is not known whether gametes from H. erythrogramma adults acclimatized to 24°C would have successful development in a +4°C treatment (28°C). Although this seems unlikely, the strong influence of phenotypic thermal acclimatization on sea urchin reproduction and development warrants further study with respect to future SST scenarios to determine the potential adaptive capacity of fertilization and development to ocean warming. For the closely related sympatric species Heliocidaris tuberculata, parental acclimatization in nature dramatically shifts temperature tolerance of developing embryos (O'Conner & Mulley 1977).

Comparative data (controls: >80–90% fertilization, >75% normal development) on the effect of increased pCO2 and decreased pH as a single stressor on sea urchin fertilization and development are available for five species (table 2). These studies show that sea urchin fertilization and early development are only affected by pH <7.4 (above 1000 ppm CO2), levels that are well below model predictions for ocean acidification. As for H. erythrogramma, several species show a broad pH/pCO2 tolerance of fertilization and development within values predicted for climate change. In Echinometra mathaei, Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus and Strongylocentrotus purpuratus fertilization dropped from more than or equal to 90 per cent in controls to 70, 60 and 60% at pH 7.4, 7.0 and 7.0, respectively (Bay et al. 1993; Kurihara & Shirayama 2004). With regard to development, the percentage of normal S. purpuratus embryos dropped from approximately 90 per cent in controls to 70 per cent at pH 7.3 (Bay et al. 1993). Studies on the influence of pH using acid or environmental samples to lower sea-water pH show a similar tolerance of echinoderm fertilization and development to acidification (Smith & Clowes 1924; Riveros et al. 1996; Kurihara & Shirayama 2004). For H. erythrogramma, a recent study observed a drop in fertilization success from 62 per cent (s.e.=8%) at pH 8.1 to 51 per cent (s.e.=8.4%) at pH 7.7, a drop attributed to decreased sperm motility (Havenhand et al. 2008). We do not know whether sperm motility was affected in our experiments. Owing to different fertilization conditions (control 70% fertilization rate; Havenhand et al. 2008), it is not possible to directly compare our study, but we note that fertilization success in our experiments exceeded 90 per cent. The weight of evidence (table 2) suggests that, within predicted values for environmental change, sea urchin fertilization and early development are robust to decreased pH. This may be due to the low pH naturally associated with echinoderm reproduction; the internal pH of activated sperm is initially at pH 7.6 and acid is released by echinoderm eggs at fertilization (Peaucellier & Doree 1981; Holland & Gould-Somero 1982), phenomena characteristic of marine invertebrate reproduction (Holland et al. 1984). Moreover, the early life history of H. erythrogramma and other intertidal invertebrates is likely to be adapted to the broad range of pH (e.g. pH 7.4–8.9) characteristic of this habitat due to photosynthetic activity (Whooten et al. 2008).

Table 2.

pH tolerance of fertilization and early development, and pH levels producing impaired fertilization and development, in studies of sea urchins, where pH was lowered by the treatment of sea water with CO2 gas, with control fertilization ≥80–90% and development ≥75%. n.d., no data. (Asterisk indicates the individual cleavage stages scored.)

| species | pH range fertilization | pH fertilization <60–70% | pH range normal early development | pH normal development <60–70% | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongylocentrotus purpuratus | 7.3–8.2 | 7.0 | 7.5–8.3 | 7.3 | Bay et al. (1993) |

| Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus | 7.4–8.0 | 7.0 | 7.6–8.0* | 7.4 | Kurihara & Shirayama (2004) |

| Arbacia punctulata | 6.9–8.6 | 6.8 | 7.4–8.6 | 6.8 | Carr et al. (2006) |

| Echinometra mathaei | 7.6–8.1 | 7.4 | n.d. | n.d. | Kurihara & Shirayama (2004) |

| Heliocidaris erythrogramma | 7.6–8.3 | n.d. | 7.8–8.3 | n.d. | this study |

| Heliocidaris tuberculata | 7.6–8.3 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | M. Byrne, P. Selvakumaraswamy & N. A. Soars (2008, unpublished data) |

Although our results indicate that the early life-history stages of H. erythrogramma may be robust to predicted ocean acidification by 2100, decreased pH may have a negative effect on larval calcification. Echinoplutei of H. pulcherrimus reared at pH 7.8 and ambient temperature have a shorter arm skeleton, an effect that would negatively impact feeding (Kurihara & Shirayama 2004). Thus, despite the broad pH tolerance of early development, larval development may fail. That said, it has also been suggested that increased warming may somewhat ameliorate impaired skeletogenesis at ambient SST through enhancing the cellular mechanisms underlying calcification (Reynaud et al. 2003; McNeil et al. 2004), and a recent study shows that ophiuroids increase the rate of calcification in low pH conditions (Wood et al. 2008). Clearly, more empirical data are needed to place the prospects of marine calcification in the context of climate change.

Our results indicate that within the context of projected environmental change for eastern Australia (CSIRO Climate System Model Mk3.5), increased SST will be a more serious embryonic teratogen than acidification despite both stressors being applied simultaneously. Projections for eastern Australia indicate a SST warming up to +2–4°C in summer off the coast of New South Wales. If this coincides with current maximum SST, temperatures above 26°C may occur. Our data indicate that such an increase would be deleterious for development. Although recent investigations of the impacts of climate change on marine systems have focused on ocean acidification and biocalcification (Reynaud et al. 2003; Feely et al. 2004; Fine & Tchernov 2007; Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2007; Wood et al. 2008), if temperatures increase beyond the inherent thermal adaptive capacity of successful reproduction, marine embryos may not reach the calcifying stage. More importantly, increased temperature may impair early developmental mechanisms (e.g. cleavage, gastrulation) that are conserved across the Metazoa, with broad deleterious effects for all marine ecosystems.

Two major stressors set to change in the global ocean are temperature and pH. While it is important to understand the influence of these stressors in isolation, it is imperative to understand their interactive effects. Examination of these two stressors on the early life-history stages of H. erythrogramma, and the results of other studies of benthic taxa where interactive effects of the two major climate change stressors were investigated (Renaud et al. 2003; Anthony et al. 2008), emphasize the urgent need for experiments cognizant of current local conditions and stressors and within the range of projected values (Poloczanska et al. 2007; Fabry et al. 2008; Przeslawski et al. 2008). Our study also highlights the potentiality that adaptive phenotypic plasticity may help buffer the negative effects of warming, as suggested for corals (Wooldridge et al. 2005; Edmunds & Gates 2008). In reality, however, marine gametes and embryos are exposed to multiple stressors in addition to those associated with global warming, and stressors are unlikely to act independently (Przeslawski et al. 2005, 2008). This presents a considerable challenge as we attempt to predict how benthic marine invertebrates will fare as the oceans warm and acidify.

Acknowledgments

The CSIRO team, Dr A. Hobday, Dr R. Matear and Dr B. Tilbrook, are thanked for their advice on climate change scenarios and ocean chemistry. Professor F. Millero, University of Miami, is also thanked for his advice on ocean chemistry. We thank the reviewers for their helpful comments. This work was supported by grants from the Australian Research Council (S.A.D. and M.B.) and Australian Greenhouse Office Scholarship (H.D.N.).

References

- Anthony K.R.N., Kline D.I., Diaz-Pulido G., Dove S., Hoegh-Guldberg O. Ocean acidification causes bleaching and productivity loss in coral reef builders. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17442–17446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804478105. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804478105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay S., Burgess R., Nacci D. Status and applications of echinoid (phylum Echinodermata) toxicity test methods. In: Landis W.G., Hughes J.S., Lewis M.A., editors. Environmental toxicology and risk assessment. American Society for Testing and Materials; Philadelphia, PA: 1993. pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham B.L., Bacigalupi M., Johnson L.G. Temperature adaptations of embryos from intertidal and subtidal sand dollars (Dendraster excentricus, Wschscholtz) Northwest Sci. 1997;71:108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne M., Emlet R.B., Cerra A. Ciliated band structure in planktotrophic and lecithotrophic larvae of Heliocidaris species (Echinodermata: Echinoidea): a demonstration of conservation and change. Acta Zool. 2001;82:189–199. doi:10.1046/j.1463-6395.2001.00079.x [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira K., Wickett M.E. Anthropogenic carbon and ocean pH. Nature. 2003;425:365. doi: 10.1038/425365a. doi:10.1038/425365a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr R.S., Biedenbach J.M., Nipper M. Influence of potentially confounding factors on sea urchin porewater toxicity tests. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2006;51:573–579. doi: 10.1007/s00244-006-0009-3. doi:10.1007/s00244-006-0009-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.P., Chen B.Y. Effects of high temperature on larval development and metamorphosis of Arachnoides placenta (Echinodermata Echinoidea) Mar. Biol. 1992;112:445–449. doi:10.1007/BF00356290 [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S., Havenhand J., Thorndyke W., Peck L., Thorndyke M. Near-future level of CO2-driven ocean acidification radically affects larval survival and development in the brittlestar Ophiothrix fragilis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008;373:285–294. doi:10.3354/meps07800 [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds P.J., Gates R.D. Acclimatization in tropical coral reefs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008;361:307–310. doi:10.3354/meps07556 [Google Scholar]

- Fabry V.J., Seibel B.A., Feely R.A., Orr J.C. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine fauna and ecosystem processes. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2008;65:414–432. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsn048 [Google Scholar]

- Farmanfarmaian A., Giese A.C. Thermal tolerance and acclimation in the western purple sea urchin, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Physiol. Zool. 1963;36:237–343. [Google Scholar]

- Feely R., Sabine C.L., Lee K., Berelson W., Kleypas J., Fabry V.J., Millero F.J. Impact of anthropogenic CO2 on the CaCO3 systems in the oceans. Science. 2004;305:362–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1097329. doi:10.1126/science.1097329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine M., Tchernov D. Scleractinian coral species survive and recover from decalcification. Science. 2007;315:1181. doi: 10.1126/science.1137094. doi:10.1126/science.1137094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa H. Differences in temperature dependence of early development of sea urchins with different growing seasons. Biol. Bull. 1989;176:96–102. doi:10.2307/1541576 [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa H. Variation in embryonic temperature sensitivity among groups of the sea urchin, Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus, which differ in their habitats. Zool. Sci. 1995;12:583–589. [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa H., Shigei M. Correlation of embryonic temperature sensitivity of sea urchins with spawning season. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1990;136:123–139. doi:10.1016/0022-0981(90)90191-E [Google Scholar]

- Havenhand J.N., Butler F.R., Thorndyke M.C., Williamson J.E. Near-future levels of ocean acidification reduce fertilisation success in a sea urchin. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:651–652. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.015. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays G.C., Richardson A.J., Robinson C. Climate change and marine plankton. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005;20:338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.03.004. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh-Guldberg O., et al. Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science. 2007;318:1737–1742. doi: 10.1126/science.1152509. doi:10.1126/science.1152509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland L.Z., Gould-Somero M. Fertilization acid of sea urchin eggs: evidence that it is H+ not CO2. Dev. Biol. 1982;92:549–552. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90200-7. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(82)90200-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland L.Z., Gould-Somero M., Paul M. Fertilization acid release in Urechis eggs. I. The nature of the acid and the dependence of acid release and egg activation on external pH. Dev. Biol. 1984;103:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90322-1. doi:10.1016/0012-1606(84)90322-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2007. The fourth assessment report of the IPCC. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L.G., Babcock R.C. Temperature and the larval ecology of the crown-of-thorns starfish, Acanthaster planci. Biol. Bull. 1994;168:419–443. doi: 10.2307/1542287. doi:10.2307/1542287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N. Comparative sensitivity of various developmental stages of sea urchins to some chemicals. Mar. Biol. 1980;58:163–171. doi:10.1007/BF00391872 [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara H., Shirayama Y. Effects of increased atmospheric CO2 on sea urchin early development. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2004;274:161–169. doi:10.3354/meps274161 [Google Scholar]

- Laegdsgaard P., Byrne M., Anderson D.T. Reproduction of sympatric populations of Heliocidaris erythrogramma and H. tuberculata (Echinoidea) in New South Wales. Mar. Biol. 1991;110:359–374. doi:10.1007/BF01344355 [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, E. & Wallace, D. W. R. 1998 Program developed for CO2 system calculations. ORNL/CDIAC-105, Oak Ridge national Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, TN, USA.

- McNeil B.I., Matear R.J., Barnes D.J. Coral reef calcification and climate change: the effect of ocean warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004;31:L22309. doi:10.1029/2004GL021541 [Google Scholar]

- Michaelidis B., Ouzounis C., Paleras A., Pörtner H.O. Effects of long-term moderate hypercapnia on acid–base balance and growth rate in marine mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005;293:109–118. doi:10.3354/meps293109 [Google Scholar]

- Newell, B. S. 1961 Hydrology of south-eastern Australian waters. CSIRO Aust. Div. Fish. Oceanogr. Tech. Pap No. 10.

- O'Conner C., Mulley J.C. Temperature effects on periodicity and embryology, with observations on the population genetics, of the aquacultural echinoid Heliocidaris tuberculata. Aquaculture. 1977;12:99–114. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(77)90176-4 [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor M.I., Bruno J.F., Gaines S.D., Halpern B.S., Lester S.E., Kinlan B.P., Weiss J.M. Temperature control of larval dispersal and the implications for marine ecology, evolution, and conservation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:1266–1271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603422104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603422104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive P.J.W. Annual breeding cycles in marine invertebrates and environmental temperature: probing the proximate and ultimate causes of reproductive synchrony. J. Therm. Biol. 1995;20:79–90. doi:10.1016/0306-4565(94)00030-M [Google Scholar]

- Palmer A.R. Temperature sensitivity, rate of development, and time to maturity: geographic variation in laboratory-reared Nucella and a cross-phyletic overview. In: Wilson W.H., Stricker S.A., Shinn G.L., editors. Reproduction and development of marine invertebrates. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 1994. pp. 177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Peaucellier G., Doree M. Acid release at activation and fertilization of starfish oocytes. Dev. Growth Differ. 1981;23:287–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.1981.00287.x. doi:10.1111/j.1440-169X.1981.00287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechenik J.A. Environmental influences on larval survival and development. In: Giese A.C., Pearse J.S., editors. Reproduction of marine invertebrates. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1987. pp. 551–608. [Google Scholar]

- Poloczanska E.S., et al. Climate change and Australian marine life. Oceanog. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev. 2007;45:407–478. [Google Scholar]

- Pörtner H.O., Langenbuch M., Reipschläger A. Biological impact of elevated ocean CO2 concentrations: lessons from animal physiology and earth history. J. Oceanogr. 2005;60:705–718. doi:10.1007/s10872-004-5763-0 [Google Scholar]

- Przeslawski R., Davis A.R., Benkendorff K. Synergies, climate change and the development of rocky shore invertebrates. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2005;11:515–522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.00918.x [Google Scholar]

- Przeslawski R., Ahyong S., Byrne M., Wörheide G., Hutchings P. Beyond corals and fish: the effects of climate change on non-coral benthic invertebrates of tropical reefs. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2008;14:2773–2795. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01693.x [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud S., Leclercq N., Romaine-Lioud S., Ferrier-Pagés C., Jaubert J., Gattuso J.-P. Interacting effects of CO2 partial pressure and temperature on photosynthesis and calcification in a scleractinian coral. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2003;9:1660–1668. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00678.x [Google Scholar]

- Riveros A., Zuñiga M., Larrain A., Becerra J. Relationships between fertilization of the southeastern Pacific sea urchin Arbacia spatuligera and environmental variables in polluted coastal waters. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1996;134:159–169. doi:10.3354/meps134159 [Google Scholar]

- Roller R.A., Stickle W.B. Effects of temperature and salinity acclimations of adults on larval survival, physiology, and early development of Lytechinus variegatus (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) Mar. Biol. 1993;116:583–591. doi:10.1007/BF00355477 [Google Scholar]

- Sconzo G., Amore G., Capra G., Giudice G., Cascino D., Ghersi G. Identification and characterization of a constitutive HSP75 in sea urchin embryos. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;234:24–29. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.9996. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.9996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H.W., Clowes G.H.A. The influence of hydrogen ion concentration on the fertilization process in Arbacia, Asterias and Chaetopterus eggs. Biol. Bull. 1924;47:333–334. doi:10.2307/1536693 [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg F.J. Comparative physiology: latitudinal effects of physiological properties of animal populations. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 1962;24:517–546. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.24.030162.002505. doi:10.1146/annurev.ph.24.030162.002505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser M.E. Keeping up with a warming world; assessing the rate of adaptation to climate change. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2007;275:649–659. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0997. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whooten J.T., Pfister C.A., Forester J.D. Dynamic patterns and ecological impacts of declining ocean pH in a high-resolution multi-year dataset. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:18848–18853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810079105. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810079105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood H.L., Spicer J.I., Widdicombe S. Ocean acidification may increase calcification rates, but at a cost. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2008;275:1767–1773. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0343. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge S., Done T., Berkelmans R., Jones R., Marshall P. Precursors for resilience in coral communities in a warming climate: a belief network approach. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2005;295:157–169. doi:10.3354/meps295157 [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Mihashi K. Temperature-independent period immediately after fertilization in sea urchin eggs. Biol. Bull. 1998;195:107–111. doi: 10.2307/1542817. doi:10.2307/1542817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]