Abstract

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can decrease the risk of colorectal cancer; however, it has not been established if this effect is solely through their ability to inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX). In this study the effects of indomethacin, a potent NSAID and nonselective COX inhibitor, was examined in LS174T human colon cancer cells. These cells were found to express EP2 prostanoid receptors, but not the EP1, EP3 or EP4 subtypes. Pretreatment of LS174T cells with indomethacin produced a complete inhibition of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)-stimulated cyclic AMP (cAMP) formation in a dose dependent manner with an IC50 of 21 μM. Interestingly, the inhibition of PGE2-stimulated cAMP formation by indomethacin was accompanied by a decrease in EP2 mRNA expression and by a decrease in the whole cell specific binding of [3H]PGE2. Thus, treatment of LS174T cells with indomethacin causes a down-regulation of EP2 prostanoid receptors expression that may be independent of COX inhibition.

Keywords: prostaglandin E2, PGE2, EP2 receptor, cAMP, indomethacin, NSAIDs, G-protein coupled receptors, LS174T cells

Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 is upregulated in colorectal cancer and is responsible for the increased biosynthesis of prostanoids that occurs in this disease. Of the five major prostanoids that are derived from the initial actions of COX-2, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is the most abundant in colorectal cancer. PGE2 produces its cellular signaling through the activation of G-protein coupled receptors, known as the EP receptors. There are four subtypes of EP receptors designated as EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4 [1]. Classically the EP1 and EP3 receptors couple to Gαq and Gαi to activate Ca2+ signaling and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase, respectively. The EP2 and EP4 receptors couple to Gαs to stimulate adenylyl cyclase and activate cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) signaling [2]. More recently EP4 receptors have been shown to couple to Gαi and activate phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling [3].

There is considerable evidence that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have activity in the prevention and possible treatment of cancer. For example, the risk of developing colorectal cancer is decreased by 40% to 50% in individuals taking NSAIDs regularly [4]. The principal pharmacological activity of the NSAIDs is to inhibit COX-1 and/or COX-2, thereby decreasing the biosynthesis of all prostanoids and preventing the activation of their cognate receptors. Gene knockout studies of the prostanoid receptors have implicated individual receptor subtypes in the development and progression of cancer. For example, deletion of the EP2 receptor in adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) Δ716 mice, a mouse model for human familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), reduced the size and number of intestinal polyps [5]. The up regulation of COX-2 in intestinal polyps from control APCΔ716 mice was also suppressed in EP2 receptor deficient APCΔ716 mice; suggesting that EP2 receptors provide a positive feedback on the expression of COX-2. In contrast, the formation of aberrant crypts (preneoplastic lesions) following treatment with the colon carcinogen, azoxymethane, was unaffected in EP2 receptor deficient mice [6]. In EP4 knockout mice, however, the formation of aberrant crypts was decreased following treatment with azoxymethane.

Studies of EP2 and EP4 receptor signaling also reveal links to pathways that are activated in colorectal cancer. Thus, mutations in APC lead to unregulated activation of the β-catenin/Tcf signaling pathway and are strongly associated with the development and progression of colorectal cancer [7]. We have previously found that PGE2 stimulation of HEK cells expressing either the human EP2 or EP4 receptors can activate β-catenin/Tcf signaling, although by different mechanisms [8]. Thus, the involvement of prostanoid receptors in colorectal carcinogenesis, particularly the Gαs-coupled EP2 and EP4 receptors, is supported by a variety of epidemiological, genetic and biochemical evidence.

It is well established that NSAIDs inhibit the formation of prostanoids in vivo [9]; however, NSAIDs possess other pharmacological activities [10]. In addition, as noted above, there is a feedback loop involving EP2 receptors and COX-2 expression [5] and a feedback loop involving EP4 receptors and COX-2 has been proposed [6]. Thus, it is possible that NSAIDs could modulate other components of prostanoid signaling. To examine other possible effects of NSAIDs on prostanoid receptor signaling, we treated LS174T cells, a human colon cancer cell line, with indomethacin, a potent and nonselective inhibitor of COX-1 and COX-2. We found that indomethacin strongly decreased PGE2 stimulated cAMP formation and was associated with a decrease in EP2 receptor mRNA expression and a decrease in whole cell [3H]PGE2 binding. To the best of our knowledge, down regulation of EP2 prostanoid receptor expression by NSAIDs has not been previously reported.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

LS174T human colon cancer cell lines were maintained in Minimum Essential Medium-alpha (α-MEM; Invitrogen) containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

RT-PCR

Reverse transcription (RT) was done using the AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega) and approximately 0.2 μg of RNA/sample that has been pretreated with DNase I (Promega). This was followed by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using an initial incubation of 94 oC for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 oC for 20 sec, 60 oC for 30 sec and 72 oC for 60 sec. The human EP receptor primer pairs were exactly according to Shoji et al. [11] and the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) primer pairs were described previously [12]. Product sizes were 317 base pairs (bp) for EP1, 216 bp for EP2, 300 bp for EP3, 433 bp for EP4 and 737 bp for GAPDH. The products were resolved by electrophoresis on 2.0% agarose gels.

cAMP Assay

Cells were cultured in 6-well plates and sixteen hours prior to the experiments, cells were switched from their regular culture medium to Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) containing 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were pretreated with final concentrations of either the vehicle, 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (Me2SO), or 3 μM to 300 μM indomethacin for 16 hrs at 37 oC. Cells were then treated with 0.1 mg/ml isobutylmethyl-xanthine (Sigma) for 15 min followed by treatment with either vehicle (0.1% Me2SO), 1 nM to 10 μM PGE2 (Cayman) or 10 μM forskolin (Sigma) for 60 min at 37 oC. Experiments were terminated by the removing the media and placing the cells on ice. The cAMP formation was measured as described previously [8]. The amount of cAMP present was calculated from a standard curve prepared using cold cAMP and was expressed as pmol per 5 x 104 cells.

Whole Cell Radioligand Binding Assay

Cells were cultured in 6 cm dishes and were incubated for 16 hrs at 37 oC with final concentrations of vehicle (0.1% Me2SO) or 30 μM indomethacin. Cells were then trypsinized, centrifuged at 500 × g for 2 min, and resuspended at a concentration of 107 cells/ml in ice-cold MES buffer consisting of 10 mM MES (pH 6.0), 0.4 mM EDTA, and 10 mM MnCl2. [3H]PGE2 binding was performed using 100 μl of sample as described previously [8], and radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation counting.

Results

LS174T cells express endogenous EP2 receptors

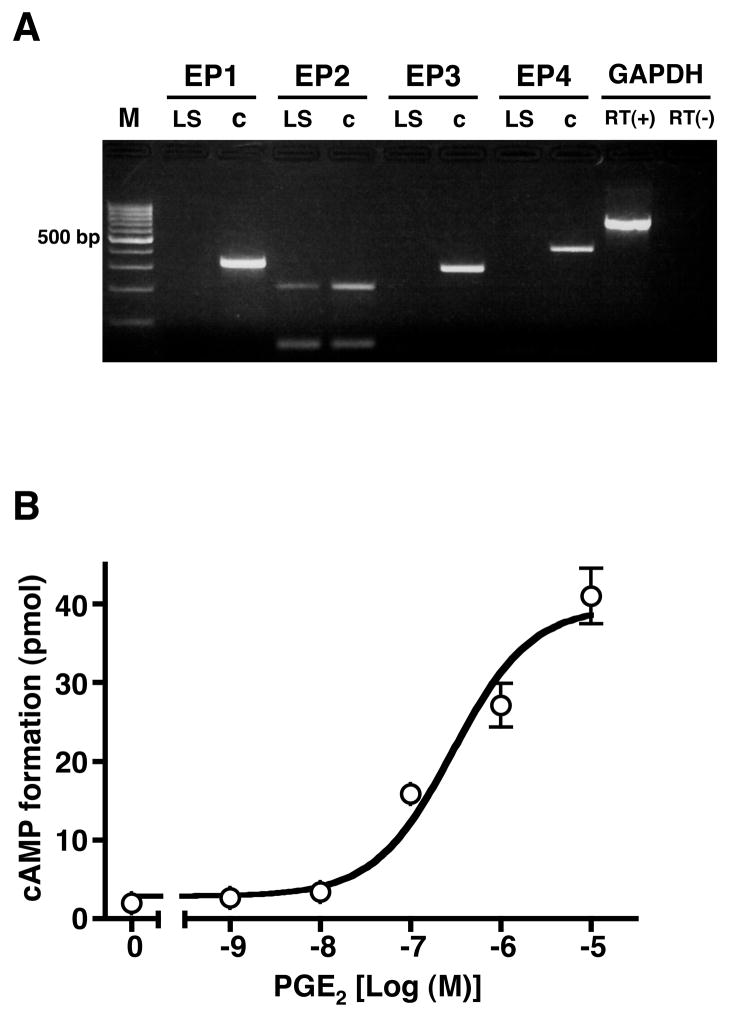

The expression of mRNA encoding the EP prostanoid receptor subtypes was examined by RT-PCR in total RNA obtained from LS174T human colon cancer cells. Total RNA prepared from HEK cells stably expressing either the human EP1, EP2, EP3 or EP4 prostanoid receptors was used for the positive controls. Figure 1A shows there was no detectable expression of mRNA encoding the human EP1, EP3 and EP4 receptor subtypes, however, mRNA encoding the human EP2 receptor was present in total RNA from LS174T cells. Agonist stimulation of EP2 receptors is well known to activate adenylyl cyclase and increase the formation of intracellular cAMP. Therefore, intracellular cAMP formation was examined in LS174T cells treated with increasing concentrations of PGE2. As shown in Figure 1B, PGE2 produced a dose dependent stimulation of cAMP formation with an EC50 of ~340 nM and a maximal stimulation of ~14 fold over basal cAMP levels. Together these results support the hypothesis that the stimulation of intracellular cAMP formation by PGE2 in LS174T cells is through the activation of EP2 prostanoid receptors.

Figure 1. Determination of mRNA encoding the human EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4 prostanoid receptor subtypes (A) and stimulation of intracellular cAMP formation by PGE2 in LS174T cells (B).

A. Total RNA from LS174T cells (LS) and positive control RNA (c) from HEK cells stably expressing the human EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4 receptors was isolated and subjected to RT-PCR as described in “Materials and Methods” using primer pairs that were specific for each of the human EP receptor subtypes. Primers for GAPDH were used in reactions in which reverse transcriptase (RT) was either present (+) or absent (−). Shown is a representative photograph from one of three independent experiments of the PCR products obtained following agarose gel electrophoresis and staining with ethidium bromide. Molecular size standards (M) are in the first lane. B. LS174T cells were treated with either vehicle (0) or the indicated concentrations of PGE2 for 60 min and cAMP formation was determined as described in “Materials and Methods”. Data are the means ± S.D. from one of four independent experiments each performed in duplicate.

Indomethacin inhibits PGE2 stimulated cAMP formation in LS174T cells

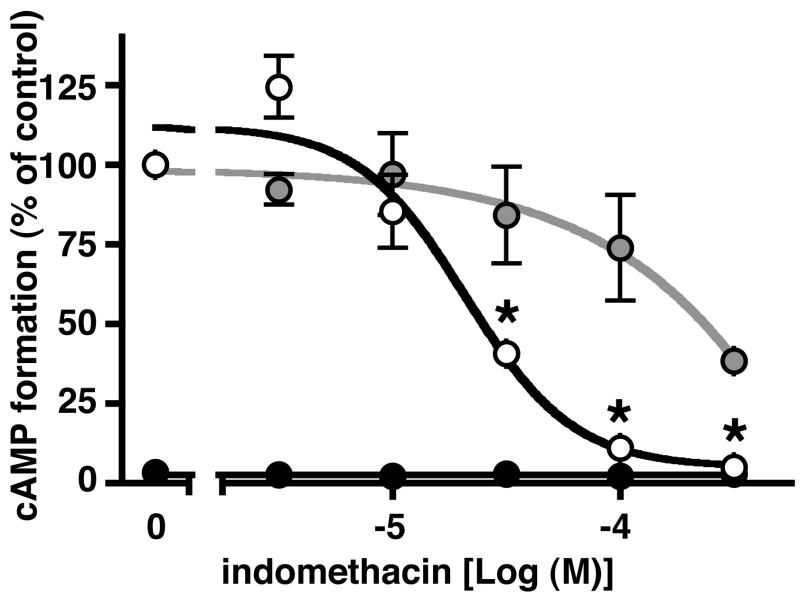

The principal pharmacological activity of the NSAIDs is inhibition of COX-1 and/or COX-2. However, there is evidence that individual NSAIDs have pharmacological activities that are COX independent and which may involve the regulation of gene expression. We were interested, therefore, to examine the effects of indomethacin with respect to the stimulation of intracellular cAMP formation by PGE2 and by forskolin in LS174T cells. Cells were pretreated with increasing concentrations of indomethacin from 3 to 300 μM for 16 hrs and cAMP formation was measured following stimulation with either 1 μM PGE2 or 10 μM forskolin for 60 mins. As shown by the open circles in Figure 2 pretreatment with indomethacin produced a dose-dependent decrease in PGE2 stimulated cAMP formation with an IC50 of ~21 μM. On the other hand, as shown by the grey circles in Figure 2, pretreatment of LS174T cells with indomethacin had relatively little effect on forskolin stimulated cAMP formation, except at the highest concentration of indomethacin. Thus, pretreatment with 300 μM indomethacin appeared to have a nonspecific effect on the stimulation of cAMP formation, perhaps representing toxicity, and it was observed that ~10% of the cells detached from the culture dish at this concentration of indomethacin. However, no obvious morphological changes or cell detachment was observed following pretreatment of LS174T cells with concentrations of indomethacin below 300 μM. Note that following pretreatment with 100 μM indomethacin the inhibition of PGE2 stimulated cAMP formation was nearly complete, whereas, the inhibition of forskolin stimulated cAMP formation was only ~25% and not significantly different, statistically (ANOVA, p > 0.05), from the control cells. The black circles in Figure 2 show that pretreatment with indomethacin itself, i.e. in the absence of PGE2 stimulation, had no effect on basal cAMP formation.

Figure 2. Effect of indomethacin pretreatment of LS174T cells on PGE2 and on forskolin stimulated cAMP formation.

Cells were pretreated with either vehicle (0 indomethacin) or 3 μM to 300 μM indomethacin for 16 hrs followed by treatment with either vehicle (black circles), 1 μM PGE2 (open circles) or 10 μM forskolin (gray circles) for 60 min. cAMP formation was determined as described under “Materials and Methods”. Data are normalized to the cAMP formation obtained following PGE2 stimulation of control cells that were not pretreated with indomethacin (0 indomethacin) and are the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments each performed in duplicate. *, p < 0.05, analysis of variance, as compared with PGE2 stimulated control cells that were not pretreated with indomethacin.

Indomethacin decreases EP2 receptor mRNA expression in LS174T cells

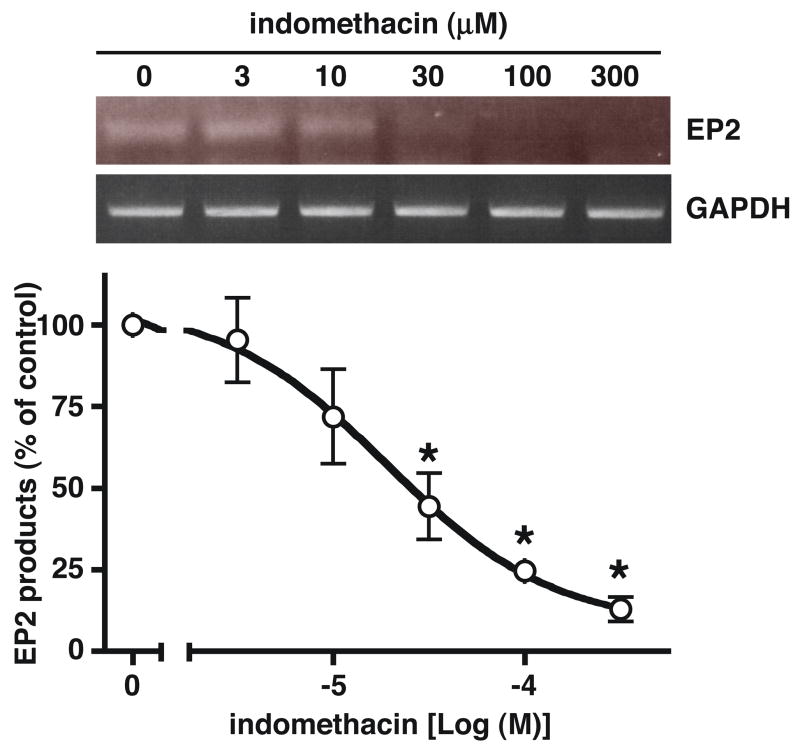

RT-PCR was used to measure mRNA encoding the EP prostanoid receptor to determine if the decrease in PGE2 stimulated cAMP formation following pretreatment of LS174T cells with indomethacin involved a possible down regulation of EP2 receptor expression. As shown in the upper panel of Figure 3, pretreatment of LS174T cells with increasing concentrations of indomethacin for 16 hrs resulted in a progressive decrease in the expression of mRNA encoding the EP2 receptor, but had virtually no effect on the expression of mRNA encoding GAPDH. The pooled RT-PCR results from three independent experiments are shown graphically in Figure 3 as a ratio of the products obtained with the EP2 primers divided by the products obtained with the GAPDH primers. The data show that pretreatment of LS174T cells with indomethacin produced a dose-dependent decrease in the expression of EP2 receptor mRNA with an IC50 of ~20 μM.

Figure 3. Effect of indomethacin pretreatment of LS174T cells on the expression of mRNA encoding the human EP2 prostanoid receptor and GAPDH.

LS174T cells were treated with either vehicle (0 indomethacin) or 3 μM to 300 μM indomethacin for 16 hrs and were then trypsinized and subjected to RT-PCR as described under “Materials and Methods”. The upper panel shows a photograph of the PCR products obtained from a representative experiment following agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. The graph below shows the pooled results (mean ± S.D.) from three independent experiments in which the PCR products were quantitated by densitometry and expressed as the ratio of the product obtained using the EP2 primers divided by the product obtained using the GAPDH primers. Data are normalized to the vehicle treated control cells (0 indomethacin). *, p < 0.05, analysis of variance, as compared with the vehicle treated control cells.

Indomethacin does not affect EP3 and EP4 receptor mRNA expression in LS174T cells

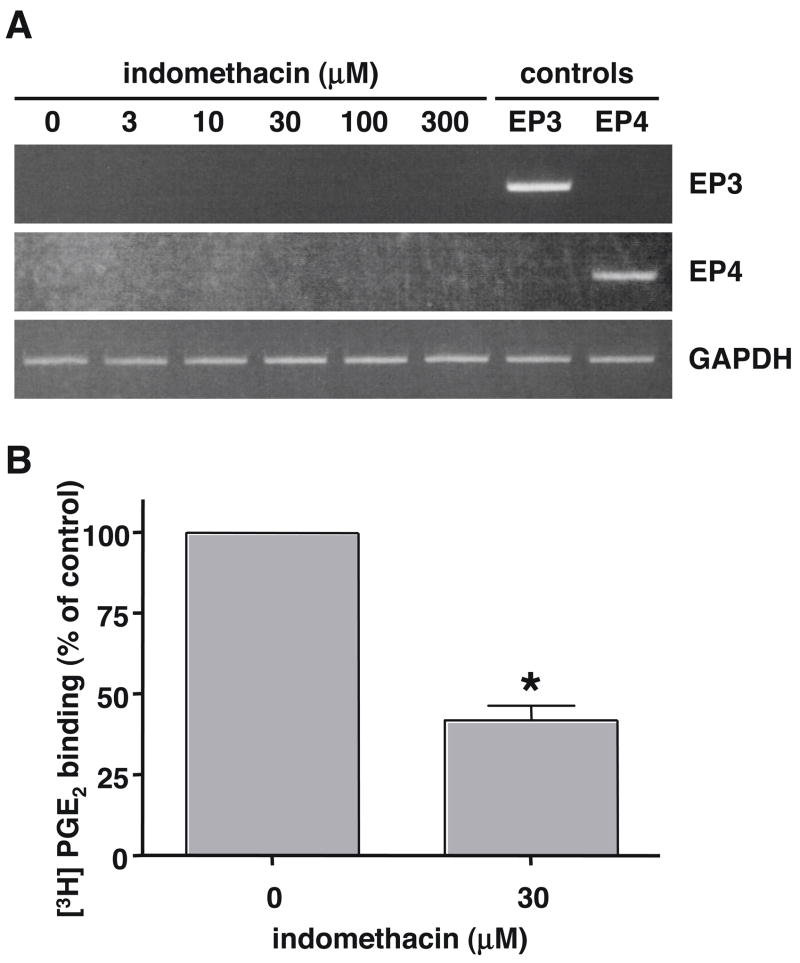

In addition to the possible down regulation of EP2 receptor expression, another mechanism that could explain a decrease in PGE2 stimulated cAMP formation following the pretreatment of LS174T cells with indomethacin could involve the possible up regulation of an EP receptor coupled to Gαi. Thus, up regulation of EP3 receptors, which are well known to couple to Gαi, or even EP4 receptors, which have been recently shown to couple to Gαi as well as Gαs [3], could have the potential decrease the formation of intracellular cAMP by PGE2 through the inhibition adenylyl cyclase. We, therefore, used RT-PCR analysis to examine the potential up regulation of mRNA encoding the human EP3 and EP4 prostanoid receptors following the treatment of LS174T cells with increasing concentrations of indomethacin. As shown in Figure 4A there was no detectable expression of mRNA encoding either the EP3 or EP4 receptors in RNA isolated from either vehicle treated LS174T cells (0 indomethacin) or cells that had been treated with 3 to 300 μM indomethacin.

Figure 4. Effect of indomethacin pretreatment of LS174T cells on the expression of mRNA encoding the human EP3 and EP4 prostanoid receptors (A) and on the whole cell binding of [3H]PGE2 (B).

ALS174T cells were treated with either vehicle (0 indomethacin) or 3 μM to 300 μM indomethacin for 16 hrs and total RNA was isolated and subjected to RT-PCR as described in “Materials and Methods” using primer pairs that were specific for the human EP3 and EP4 prostanoid receptor subtypes or for GAPDH. Positive control RNA (controls) was obtained from HEK cells stably expressing the human EP3 and EP4 receptors. Shown is a representative photograph of the PCR products obtained following agarose gel electrophoresis and staining with ethidium bromide from one of three independent experiments. B. LS174T cells were treated with either vehicle or 30 μM indomethacin for 16 hrs and were then rinsed with fresh media and assayed for the specific binding of [3H]PGE2 as described in “Materials and Methods.” Data are the means ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments each performed in duplicate. Data are normalized to the vehicle treated control cells (0 indomethacin). *, p < 0.05, t-test, as compared with the vehicle treated control cells.

Indomethacin decreases the whole cell specific binding of [3H]PGE2 in LS174T cells

Whole cell binding of [3H]PGE2 was used to determine if the decrease in EP2 mRNA expression, observed following the pretreatment of LS174T cells with indomethacin, was associated with a corresponding down regulation of EP2 receptor expression on the cell surface. Figure 4B shows that when LS174T cells were pretreated with 30 μM indomethacin for 16 hrs there was an ~60% decrease in the whole cell specific binding of [3H]PGE2 as compared to the vehicle treated control cells. Thus, the decrease in the mRNA expression of EP2 receptor following treatment of LS174T cells with indomethacin is associated with a down regulation of EP2 receptor expression on the cell surface and probably explains the decrease in PGE2 stimulated cAMP formation caused by pretreatment of LS174T cells with indomethacin.

Discussion

Molecular biological studies of EP2 and EP4 receptor signaling suggest that their link with carcinogenesis may involve stimulation of β-catenin/Tcf transcriptional activation, a pathway classically associated with the Wnt signaling cascade and often activated in colorectal cancer. For example, we have previously shown that both the human EP2 and EP4 receptors stimulate β-catenin/Tcf transcriptional, but through different molecular mechanisms. Thus, stimulation of β-catenin/Tcf signaling by the EP2 receptor primarily involves the activation of cAMP and protein kinase A (PKA) by coupling through Gαs. On the other hand, EP4 receptors stimulate β-catenin/Tcf signaling primarily through the activation phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) by coupling through Gαi [3, 13]. In this paper, we show that EP2 receptors are expressed in LS174T cells, a cell line derived from a human colorectal adenocarcinoma, and that activation of these receptors by PGE2 stimulates the formation of intracellular cAMP.

Previous studies have also shown the stimulation of cAMP formation by PGE2 in LS174T cells [14] and have reported that these cells express a low level of mRNA encoding the EP4 and EP3 receptor subtypes in addition to the EP2 receptor [15]. In the latter study, activation of EP4 receptors increased cell migration by a mechanism involving the activation of PI3K. Under the conditions of our cell culture, however, we could not detect the presence of EP3 or EP4 mRNA nor did we observe PGE2 stimulation of cell migration (data not shown). There is no obvious explanation for these differences except that it known that in vivo colon cancer cells can undergo transitions in which during metastasis they differentiate to a more mesenchymal-like phenotype, following which they return to a more epithelial-like phenotype [16]. Changes in cellular signaling occur during these transitions; thus, β-catenin/Tcf signaling is associated with the epithelial-like phenotype, but not with the mesenchymal-like phenotype. It is possible, therefore, just as the local tumor environment influences the cell phenotype, the specific cell culture conditions may influence the either the level of expression or types of receptor subtypes that are expressed.

Recent findings suggest that EP4 receptors may be more involved in the early stages of colon carcinogenesis [17], whereas, EP2 receptors may be more important for cancer growth [18]. In addition, Gutkind and colleagues have reported that EP2 receptors mediate the activation of PI3K signaling and stimulation cancer cell growth; however, they did not actually examine the expression of the endogenous EP receptor subtypes in the cells they used (DLD-1 colon cancer cells) nor did they characterize the pharmacology of the response [19]. Given that DLD-1 cells have been reported to express EP1, EP2 and EP4 receptors [11] it would seem premature to attribute the activation of PI3K signaling and stimulation of cell growth exclusively to EP2 receptors in these cells. In any event it is likely that depending upon the cell culture conditions either the EP2 receptor alone, or the EP2 and EP4 receptors together are expressed in LS174T cells and that the expression of these receptors is related to the carcinogenic heritage of LS174T cells.

Our finding of the down regulation of EP2 receptor expression by indomethacin is interesting from the standpoint that it offers another mechanism by which indomethacin, and perhaps other NSAIDs, could have anti-cancer activity besides the inhibition of prostanoid biosynthesis per se. The exact mechanism of this down regulation is unclear but several lines of evidence suggest that it might be independent of the inhibition of COX-1 and/or COX-2. For example, the IC50 for both the indomethacin induced decrease of PGE2 stimulated cAMP formation and for the inhibition of EP2 receptor mRNA expression was ~20 μM; whereas, the IC50’s for the inhibition of COX-1 and COX-2 by indomethacin are 740 nM and 970 nM, respectively [20]. Additionally, basal levels of cAMP formation in the LS174T cells are very low and are not apparently affected by indomethacin (Figure 2) suggesting that any constitutive COX activity and PGE2 production is not sufficient to cause appreciable activation of the endogenous EP2 receptors, as least with respect to cAMP formation. This is corroborated by a previous study that found a low level of COX-2 expression in LS174T cells, but that it was not associated with any detectable PGE2 production [21].

It is possible, therefore, that the down regulation of EP2 receptor expression by indomethacin in LS174T cells involves a COX independent mechanism. Thus, NSAIDs, and indomethacin in particular, have long been associated with a variety of COX independent actions [10]. For example, indomethacin has been reported to have agonist activity on the PGD2 receptor subtype DP2 (also known as, CRTH2) with an EC50 for Ca2+ mobilization of ~50 nM [22]. In addition, indomethacin can stimulate the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-λ (PPARλ) with an EC50 of ~40 μM [23]. Interestingly PPARλ agonists have been shown to down regulate EP2 receptor mRNA and protein expression in human non-small cell lung carcinoma cells and are associated with inhibition of cell growth [24]. It is possible, therefore, that the down regulation of EP2 receptor expression that we have observed following indomethacin treatment of LS174T cells involves the activation of PPARλ and further studies will be needed to examine this possibility.

In summary we have shown that treatment of LS174T cells with indomethacin results in a down regulation of EP2 receptor expression and in PGE2 stimulated intracellular cAMP formation. This decrease in PGE2 stimulated cAMP formation is not due to the possible up regulation of Gαi coupled EP3 or EP4 receptors and, thus, represents a decrease in the EP2 mediated activation of cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. The chemopreventative activity of NSAIDs against colorectal cancer is generally attributed to the inhibition of prostanoid biosynthesis and a decreased activation of prostanoid receptors, especially the EP2 and EP4 receptors. An additional mechanism of the anti-cancer effects of NSAIDs may also involve the down regulation of EP2 receptors and a decrease in the signaling pathways activated by this receptor.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Naoto Yamaguchi and the members of his laboratory in Chiba University for helpful discussion and use of equipment. J.W.R. thanks the support received the National Institutes of Health (EY11291) and Allergan Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E receptors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11613–11617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regan JW. EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptor signaling. Life Sci. 2003;74:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujino H, Regan JW. EP4 prostanoid receptor coupling to a pertussis toxin-sensitive inhibitory G protein. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:5–10. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.017749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown JR, DuBois RN. COX-2: A molecular target for colorectal cancer prevention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2840–2855. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonoshita M, Takaku K, Sasaki N, Sugimoto Y, Ushikubi F, Narumiya S, Oshima M, Taketo MM. Acceleration of intestinal polyposis through prostaglandin receptor EP2 in ApcΔ716 knockout mice. Nat Med. 2001;7:1048–1051. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mutoh M, Watanabe K, Kitamura T, Shoji Y, Takahashi M, Kawamori T, Tani K, Kobayashi M, Maruyama T, Kobayashi K, Ohuchida S, Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Involvement of prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP4 in colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segditsas S, Tomlinson I. Colorectal cancer and genetic alterations in the Wnt pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25:7531–7537. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujino H, West KA, Regan JW. Phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 and stimulation of T-cell factor signaling following activation of EP2 and EP4 prostanoid receptors by prostaglandin E2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2614–2619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patrono C, Patrignani P, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Cyclooxygenase-selective inhibition of prostanoid formation: transducing biochemical selectivity into clinical read-outs. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:7–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI13418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tegeder I, Pfeilschifter J, Geisslinger G. Cyclooxygenase-independent actions of cyclooxygenase inhibitors. FASEB J. 2001;15:2057–2072. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0390rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shoji Y, Takahashi M, Kitamura T, Watanabe K, Kawamori T, Maruyama T, Sugimoto Y, Negishi M, Narumiya S, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Downregulation of prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP3 during colon cancer development. Gut. 2004;53:1151–1158. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.028787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujino H, Regan JW. FP prostanoid receptor activation of a T-cell factor/β-catenin signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12489–12492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100039200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shao J, Jung C, Liu C, Sheng H. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates the β-catenin/T cell factor-dependent transcription in colon cancer. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26565–26572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheng H, Shao J, Washington MK, DuBois RN. Prostaglandin E2 increases growth and motility of colorectal carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18075–18081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009689200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brabletz T, Jung A, Reu S, Porzner M, Hlubek F, Schughart LA, Knuechel R, kirchner T. Variable β-catenin expression in colorectal cancers indicates tumor progression driven by the tumor environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10356–10361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171610498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamori T, Uchiya N, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Enhancement of colon carcinogenesis by prostaglandin E2 administration. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:985–990. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clevers H. Colon cancer – understanding how NSAIDs work. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:761–763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr055457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castellone MD, Teramoto H, Williams BO, Druey KM, Gutkind JS. Preostaglandin E2 promotes colon cancer cell growth through a Gs- axin-β-catenin signaling axis. Science. 2005;310:1504–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1116221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Futaki N, Takahashi S, Yokoyama M, Arai I, Higuchi S, Otomo S. NS-398, a new anti-inflammatory agent, selectively inhibits prostaglandin G/H synthase/cyclooxygenase (COX-2) activity in vitro. Prostaglandins. 1994;47:55–59. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(94)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shao J, Sheng H, Inoue H, Morrow JD, DuBois RN. Regulation of constitutive cyclooxygenase-2 expression in colon carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33952–33956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirai H, Tanaka K, Takano S, Ichimasa M, Nakamura M, Nagata K. Agonistic effect of indomethacin on a prostaglandin D2 receptor, CRTH2. J Immunol. 2002;168:981–985. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehmann JM, Lenhard JM, Oliver BB, Ringold GM, Kliewer SA. Peroxisome proliferators-activated receptors α and λ are activated by indomethacin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3406–3410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han S, Roman J. Suppression of prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP2 by PPARλ ligands inhibits human lung carcinoma cell growth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314:1093–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]