Abstract

Background and Purpose

The identification of a neuroprotective drug for stroke remains elusive. Given that mitochondria play a key role both in maintaining cellular energetic homeostasis and in triggering the activation of cell death pathways, we evaluated the efficacy of newly identified inhibitors of cytochrome c release in hypoxia/ischemia induced cell death. We demonstrate that methazolamide and melatonin are protective in cellular and in vivo models of neuronal hypoxia.

Methods

The effects of methazolamide and melatonin were tested in oxygen/glucose deprivation—induced death of primary cerebrocortical neurons. Mitochondrial membrane potential, release of apoptogenic mitochondrial factors, pro—IL-1β processing, and activation of caspase -1 and -3 were evaluated. Methazolamide and melatonin were also studied in a middle cerebral artery occlusion mouse model. Infarct volume, neurological function, and biochemical events were examined in the absence or presence of the 2 drugs.

Results

Methazolamide and melatonin inhibit oxygen/glucose deprivation—induced cell death, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, release of mitochondrial factors, pro—IL-1β processing, and activation of caspase-1 and -3 in primary cerebrocortical neurons. Furthermore, they decrease infarct size and improve neurological scores after middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice.

Conclusions

We demonstrate that methazolamide and melatonin are neuroprotective against cerebral ischemia and provide evidence of the effectiveness of a mitochondrial-based drug screen in identifying neuroprotective drugs. Given the proven human safety of melatonin and methazolamide, and their ability to cross the blood-brain-barrier, these drugs are attractive as potential novel therapies for ischemic injury.

Keywords: methazolamide, melatonin, neuroprotection, ischemic stroke

Release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria triggers a set of events leading to the activation of programmed cell death.1,2 Cytochrome c release occurs in a variety of neurological diseases, including stroke, Huntington disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.3–5 Inhibition of cytochrome c is therefore a potential therapeutic target for neuroprotection. To identify novel neuroprotective agents, we screened a library of FDA-approved drugs for inhibition of cytochrome c release. Cytochrome c release can be induced in purified mitochondria, providing a screening method for the identification of compounds which could inhibit this process.

We identified a number of drugs that inhibit cytochrome c release in purified mitochondria as well as in mutant Huntington-expressing striatal cells.6 One of these drugs, methazolamide, is neuroprotective in vivo in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington disease.6 To determine whether this screen identified protective drugs for acute neurodegenerative models, we tested 2 drugs in an experimental model of cerebral ischemia. Here we provide evidence for the neuroprotective properties of 2 of the drugs identified in the screen, methazolamide and melatonin, both in primary cerebrocortical neurons (PCNs) exposed to several cell death stimuli, as well as in vivo in cerebral ischemia. Neuroprotection in vivo is associated with inhibition of cytochrome c release and of caspase-3 activation. This report provides evidence of the efficacy of a mitochondrial-based screen in identifying drugs that are protective in an acute model of neurodegeneration and provides further support for the importance of cytochrome c release in the pathogenesis of ischemic injury.

Materials and Methods

Drugs

Methazolamide and melatonin were obtained from Sigma.

Cell Lines and Induction of Cell Death

Culture of PCNs were isolated as previously described and subjected to oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD),4 1 mmol/L H2O2,7 or 500 μmol/L NMDA7 for 18 hours. All cultures were used between days 7 to 10 after harvest. Cell death was determined by lactate dehydrogenase assay. Morphology of PCN cells was observed, chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation were analyzed with Hoechst 33342 staining (Molecular Probes; 1:5000 for 2 to 5 minutes).

Lactate Dehydrogenase Assay

The assay was performed as previously described according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche).4

Terminal dUTP Nick-End Labeling Assay

The assay was performed using the DeadEnd Fluorometric terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) system (Promega) as specified by the manufacturer. Briefly, attached PCNs were fixed with 4% methanol-free formaldehyde, permeabilized by 0.2% Triton-X-100, and incubated with the TUNEL reaction mixture for 1 hour at 37°C. After thorough washes, chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation were analyzed using a Nikon ECLIPSE TE-200 fluorescence microscope.

Western Blot

Mouse brain samples were lysed in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors.5,8 Antibody to caspase-3 was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, antibody to caspase-1 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and antibody to β-actin from Sigma.

Cellular and Tissue Fractionation

PCNs and mouse brain cytosolic fractionations were performed as described.7 Released cytochrome c or AIF was analyzed by Western blot. Antibody to cytochrome c was purchased from PharMingen, and to AIF from Sigma.

Mature IL-1β Determination

Mature IL-1β quantification was performed as previously described4 by using an ELISA kit specific for the mature form of the cytokine (R&D Systems).

Caspase-1 Activity Assay

Cell extracts and enzyme assays were performed with the ApoAlert caspase fluorescent assay kit as previously described. Caspase-1-like substrate Ac-YVAD-AFC (7-amino-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin) was purchased from Calbiochem. Released AFC was quantified in a Bio-Rad Versa Fluorometer (excitation at 400 nm and emission at 505 nm).

Determination of Mitochondrial Transmembrane Potential (ΔΨm)

PCNs were treated as indicated with or without methazolamide, or melatonin. Living cells were stained with Rhodamine 123 (Rh 123, Molecular Probes) as previously described.5,6

Measurement of Mitochondrial Permeability Transition

Rat liver mitochondria were isolated and treated as previously described.6,9

Permanent Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion

Focal cerebral ischemia was produced as described previously.4,7 Briefly, anesthesia was induced in 6- to 8-week-old C57BL/6J mice (body weight 20 to 24 g, Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) with 2% (vol/vol) isoflurane (70% N2O/30% O2) and was maintained with a 1 to 0.5% concentration. Rectal temperature was maintained between 37.0 and 37.5°C with a heating pad (Harvard Apparatus). Focal cerebral ischemia was induced by an intraluminal 7-0 nylon thread with a silicone tip (180 μm diameter) introduced into the right cervical internal carotid artery. The thread was inserted 9±1.0 mm into the internal carotid artery up to the middle cerebral artery. A laser Doppler perfusion monitor (Perimed AB) was adhered to the right temporal aspect of the animal’s skull and used to confirm middle cerebral artery flow disruption. Control animals underwent sham surgery consisting of only anesthesia and carotid artery dissection. Each animal was euthanized after surgery. The brain was removed, and the cerebral hemisphere was retained for either evaluation of infract volume or Western blot analysis.

Drug Treatment in Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion Model

Control mice were treated with a normal saline vehicle control containing 0.4% DMSO and 3% Tween-20. Methazolamide and melatonin were respectively prepared in normal saline containing 0.4% DMSO or 3% Tween-20 and administered by intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 20 mg/kg for methazolamide and 10 mg/kg for melatonin. Mice were treated either 1 hour before 30 minutes after permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO).

Determination of Infarct Volume

After 24 hours of MCAO, the mice were euthanized. Brains were rapidly removed and chilled for 2 minutes. Coronal sections (1-mm thick; n=7) were cut with a mouse brain matrix. Each slice was immersed in saline solution containing 2% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (Sigma) at 37°C for 20 minutes. After staining, each slice was scanned with an HP scanjet 4200C. The stained and unstained areas of the right hemisphere were quantified with imageJ 1.32j (NIH), and these values were used to calculate the infarct volume expressed as a percentage of the lesioned hemisphere.

Neurobehavioral Examination

Mice were assigned a neurobehavioral score at 24 hours after MCAO. A previously reported scale was used.7,10

Statistical Analysis

Densitometric quantification was performed with the Quantity One Program (Bio-Rad). Statistical significance was evaluated by t test: *probability values <0.05 were considered significant; **probability values <0.001. Drug analysis, including IC50 and maximum protection, were performed using the GraphPad Prism program.

Results

Methazolamide and Melatonin Are Neuroprotective in Oxygen Glucose Deprivation—Mediated Primary Cerebrocortical Neuronal Death

Using a purified mitochondrial screen, we identified drugs that inhibit release of cytochrome c.6 To determine whether this screen is effective at identifying drugs that are neuroprotective in acute cell death, we evaluated two of the “hits,” methazolamide and melatonin, in an in vitro model of cerebral ischemia. Exposing PCNs to OGD induces cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation, ultimately leading to cell death.4,11 Incubation with either methazolamide (100 nmol/L to 100 μmol/L) or melatonin (1 μmol/L to 100 μmol/L) resulted in statistically significant inhibition of OGD-mediated PCN cell death (Figure 1A and 1C). To determine the relative potencies of the 2 drugs, we measured the extent of cell death as a function of drug concentration. The resulting curves (plotted semilogarithmically) define the IC50 and maximum protection afforded by methazolamide (250 nmol/L and 53.45%, respectively, in Figure 1B) and melatonin (490 nmol/L and 40.59%, respectively, in Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Methazolamide and melatonin inhibit cell death of primary cerebrocortical neurons. Cell death of PCNs was induced by 3-hour exposure to OGD with or without a series of concentrations of methazolamide (A and B) and melatonin (C and D). Cell death was evaluated by the lactate dehydrogenase assay (A and C). Data from 3 independent experiments are graphed, and statistically significant differences are indicated with * if P<0.05 and ** if P<0.001. The extent of cell death (as measured by the release of lactate dehydrogenase activity) is always normalized relative to what is measured in the absence of both death stimulus and test drugs (white bar). The black bar corresponds to the extent of cell death in response to the respective stress without the test drug. Gray bars correspond to the extent of cell death with stress and the indicated concentration of the test drug. The relative cell death results are displayed graphically. The resulting curves (plotted semilogarithmically) define the IC50 and maximum protection of methazolamide (B) and melatonin (D).

Methazolamide and Melatonin Protect PCNs From a Variety of Cell Death Inducers

As described above, methazolamide and melatonin inhibit OGD-induced PCN cell death. We next evaluated whether methazolamide- or melatonin-mediated neuroprotection could be extended to additional cell death paradigms. H2O2- and NMDA-induced cell death have been used as in vitro models of oxidative damage and excitotoxic neuronal injury.7,8,12,13 We therefore evaluated the ability of methazol-amide and melatonin to protect PCNs challenged with H2O2 or NMDA. Melatonin and methazolamide inhibited both H2O2 and NMDA-induced PCN cell death in a dose dependant manner (Figure 2A, 2B, 2D, and 2E). Phase-contrast photomicrographs demonstrate H2O2-mediated loss of PCN neuritic processes (Figure 2G, lower panel), cell death-associated nuclear fragmentation, and chromatin condensation (arrows in Figure 2G, upper panel). Methazolamide (Figure 2A and 2B) and melatonin (Figure 2D and 2E) significantly inhibited cell death induced by either stimulus. Phase-contrast micrograph demonstrates that both methazolamide and melatonin not only inhibited cell death, but also partially restored normal cellular morphology. Note that Figure 2 also includes data on the cytochrome c release inhibitor minocycline (Figure 2C and 2F). Minocycline is used here as a positive control, given its demonstrated neuroprotective properties as an inhibitor of cytochrome c release.8,14,15 To provide further evidence of modulation of cell death, we performed TUNEL labeling and evaluated the neurons using a fluorescence microscope (Figure 2H). TUNEL staining revealed a clear increase of chromatin condensation and fragmentation in H2O2-treated apoptotic nuclei of PCNs as compared to control cells. Incubation of methazolamide and melatonin reduced the degree of TUNEL-positive cells. Having observed that methazolamide and melatonin prolong the survival of PCNs subjected to OGD, H2O2, and NMDA, we proceeded to study what cell death–associated molecular changes they affect.

Figure 2.

Methazolamide and melatonin inhibit cell death of primary cerebrocortical neurons under exposure to H2O2 or NMDA. Cell death of PCNs was induced by 18-hour exposure to 1 mmol/L H2O2 (A through C and G) or 500 μmol/L NMDA (D through F and G). A through F, Cell death was evaluated by the lactate dehydrogenase assay. Data from 3 independent experiments are graphed, and statistically significant differences are indicated with * if P<0.05 and ** if P<0.001. White, black, and gray bars are labeled as indicated in Figure 1. G, Phase-contrast light micrographs of control versus H2O2-treated PCNs with or without incubation with methazolamide (10 μmol/L) or melatonin (10 μmol/L) are shown as indicated (middle panel). Nuclei are stained with Hoechst 33342 (upper panel). Arrows point to apoptotic cells with condensed or fragmented chromatin. Bar=5 μm. H, TUNEL staining in cells treated with H2O2 reveals a large increase of positive nuclei with condensed chromatin and DNA fragmentation as compared to control cells. Incubation with methazolamide (10 μmol/L) or melatonin (10 μmol/L) significantly reduces the numbers of TUNEL-positive cells. Scale Bar=5 μm.

Inhibition of Mitochondrial Cell Death Pathways Contributes to Neuroprotection by Methazolamide and Melatonin

Our observation that methazolamide is neuroprotective in PCNs is the first in the literature. Now it becomes of interest to determine the effects of the compound on the molecular physiology of the cell. The ability of melatonin to inhibit neuronal cell death has been previously demonstrated,16–21 but the signaling mechanisms mediating the neuroprotective actions of melatonin remain poorly understood. Given that methazolamide and melatonin were identified by their ability to inhibit cytochrome c release from purified mitochondria, we next evaluated whether these drugs could inhibit OGD-mediated cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation.

The release of cytochrome c and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) from mitochondria trigger downstream caspase-3 activation and additional caspase-independent cell death events.1,22 Blocking the release of apoptogenic factors into the cytoplasm should inhibit cell death. Indeed, as demonstrated by Western blotting, OGD induces mitochondrial release of cytochrome c and AIF (Figure 3A and 3B). Methazolamide (Figure 3A) and melatonin (Figure 3B) effectively inhibited release of these cell death mediators. We next evaluated the activity of the downstream effector caspase-3. Western blot analysis demonstrated that caspase-3 was activated on OGD induction, and both methazolamide and melatonin effectively inhibited caspase-3 activation (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Methazolamide and melatonin inhibit the release of mitochondrial apoptogenic factors and forestall caspase-3 activation. Cell death was induced in PCNs by subjecting cells to OGD for 3 hours with or without 10 μmol/L methazolamide (A and C) or 10 μmol/L melatonin (B and C). Subsequently, cells were extracted, and either cytosolic components (A and B) or whole cell lysates (C), or supernatants (D and E) were obtained. The samples, each of which contained 50 μg of protein, were analyzed by Western blot using antibodies to cytochrome c, AIF (cytosolic components; A and B), or caspase-3 (whole cell lysates; C). Beta-actin was used as a loading control. This blot is representative of 3 independent experiments.

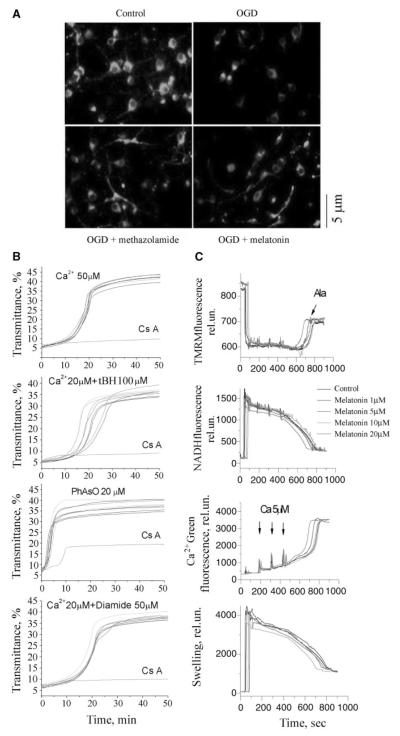

Methazolamide and Melatonin Slow Dissipation of the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Gradient in Primary Cerebrocortical Neurons

Proper mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) is critical for appropriate cellular bioenergetic homeostasis, and its loss is an important event associated with progression of mitochondrial dysfunction and leading to cellular demise.23 We therefore evaluated whether, given their neuroprotective properties, methazolamide and melatonin could inhibit the dissipation of Δψm. Comparing with the punctate Rh123 staining seen in normal Δψm in control PCNs, OGD results in a diffuse and lower intensity staining pattern as previously described4 (Figure 4A, upper panel). Both methazolamide and melatonin inhibited OGD-associated loss of mitochondrial Δψm (Figure 4A, lower panel). Hence methazolamide and melatonin treated PCNs exposed to OGD maintain proper Δψm, therefore pointing to a mechanism of action involving not only inhibition of release of apoptogenic factors, but also preservation of appropriate cellular energetics.

Figure 4.

Methazolamide and melatonin slow the dissipation of ΔΨm, but melatonin does not inhibit mPT. A, PCNs were subjected to OGD for 3 hours with or without methazolamide (10 μmol/L) and melatonin (10 μmol/L). The living cells were then stained with 2 μmol/L Rh 123 to determine the electrostatic charge of the mitochondria. B, Melatonin was investigated in the in vitro system of purified liver mitochondria that had been stimulated with Ca2+ ions. Melatonin did not prevent the induction of the mPT as judged by an unchanging degree of mitochondrial swelling. The lack of such an effect on addition of melatonin to a solution of stimulated mitochondria is illustrated in B. The same is true of mitochondria stimulated in several ways, ie, with Ca2+ ions; Ca2+ and tBH, PhAsO, or Ca2+ and diamide. The dose—response curves to these stimuli hardly change when melatonin is present at 0.01 μmol/L to 2 mmol/L. In all cases, mitochondrial swelling is monitored by a standard spectroscopic assay using light of 540 nm. C, Liver mitochondria (0.25 mg/mL) were energized with 5 mmol/L glutamate/malate and incubated with 1, 5, 10, and 20 μmol/L of melatonin in buffer containing 250 mmol/L sucrose, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 2 mmol/L KH2PO4. Mitochondria were challenged with bolus additions of 5 μmol/L Ca2+ every 2 minutes until release of sequestered Ca2+ occurred. Alamethicin (100 μg) was added in the end of each sample. Upper left panel is ΔΨm, upper right is in the buffer, lower left is NADH level, and lower right is swelling. See Methods for additional information.

Melatonin Is Not a Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Inhibitor in Isolated Mitochondria

The mitochondrial permeability transition pore consists of a multimeric complex of proteins spanning the inner and outer membranes.24,25 Its opening is a component of mitochondrial dysfunction, itself a result of such biochemical stresses as high concentrations of Ca2+ ion, oxidizing agents, thiol reactive compounds (ie, reactive aldehyde), and proapoptotic cytosolic proteins.26 The loss of ΔΨm is an early event in the cell death pathway and an important trigger of the caspase cascade.

There is no satisfactory method for directly determining the mitochondrial permeability transition in living cells. Consequently, we investigated the effects of methazolamide on this molecular event in purified mitochondria. In these experiments, mitochondrial permeability transition (mPT) was induced by Ca2+ ions, the oxidating agent organic hydroperoxide tBH, the thiol cross-linking agent PhAsO, the thiol oxidant diamide, or a combination thereof (Figure 4B, and 4C). Melatonin, similar to methazolamide,6 did not protect purified mitochondria from these chemical challenges. These observations contrast with the analogous ones using (1) minocycline, a compound that blocks the loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential both in vitro and in vivo,5,8 or (2) the heterocyclic, tricyclic, or phenothiazine-derived agents.26

Neither inhibition of the mPT nor direct effects on mitochondrial physiology appear to underlie the protection imparted by melatonin. Initial studies in isolated liver mitochondrial focused on monitoring swelling as a marker or mPT induction and tested the agents at a broad dose response range. No effects were seen, suggesting that these agents do not interfere with mPT induction across a broad concentration range. Because work in other systems, such as cultured cerebellar granular neurons, had suggested that interference with mitochondrial physiology through uncoupling and respiratory inhibition could also appear protective, we examined the effects of melatonin on basic physiological properties. Studies were done on a recently adapted fluorescence system9 that allows simultaneous measurement of membrane potential (by following TMRM fluorescence), Ca2+ flux (using Calcium Green 5N), NAD+/NADH redox status (using autofluorescence of the NAD+/NADH couple), and swelling (via light scatter). The system is an improved fluorescence-based analog of the electrode-based system we have previously used and described.26

Melatonin did not have any significant effects on ΔΨm, calcium transport, NAD+/NADH redox status, or swelling (Figure 4B). Thus, the data in Figure 3B and 3C suggest that melatonin does not mediate its protective effect by acting on basic mitochondrial physiology, including mitochondrial redox status and substrate, proton, electron, or Ca2+ transport. These data are most consistent with effects mediated outside the inner mitochondrial membrane/mitochondrial matrix, including potential targets such as bcl-2 family members (eg, bak/bax) and the elements involved in release of proapoptotic proteins. Studies are in progress to address these potential mechanisms.

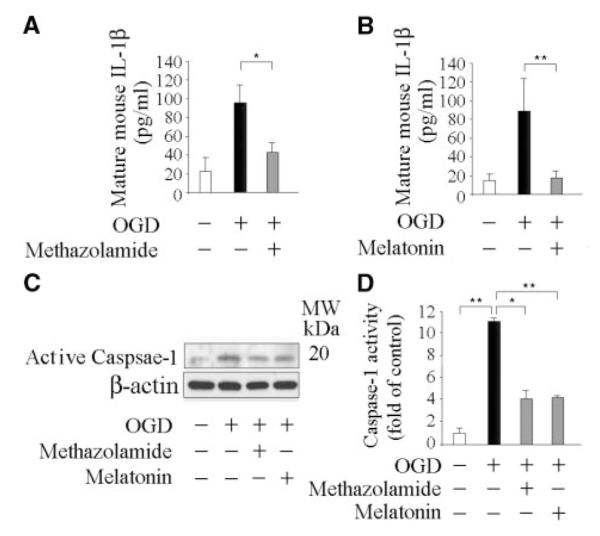

Melatonin and Methazolamide Inhibit OGD-Induced Mature IL-1β Release and Caspase-1 Activation

Caspase-1 plays a critical role as an apical activator of OGD-induced PCN death.4 The release of mature IL-1β serves as an indicator of caspase-1 activation.27 Endogenously produced IL-1β plays a role in a variety of cell death paradigms, and the inhibition of cleavage of pro-IL-1β and the secretion of mature IL-1β are associated with inhibition of cell death.4,27–29 To further evaluate the mechanisms of action of methazolamide and melatonin, using an ELISA assay specific for the mature form of IL-1β, we quantified the release of the active cytokine into conditioned medium of OGD-treated PCNs. Consistent with previous evidence that OGD treatment induces caspase-1 activation and IL-1β processing in PCNs,4 we detected a greater than 4-fold increase in the concentration of mature IL-1β (Figure 5A and 5B) and caspase-1 cleavage (p20; Figure 5C). Moreover, the release of mature IL-1β and activation of caspase-1 were significantly blocked by methazolamide (Figure 5A and 5C) and by melatonin (Figure 5B and 5C). In parallel, caspase-1 activity was measured by the hydrolysis of fluorogenic tetrapeptide substrate. Again, treatment of PCNs with either methazolamide or melatonin inhibited caspase-1 activation (Figure 5D). Taken together, our findings provide for the first time evidence demonstrating methazolamide- and melatonin-mediated inhibition of OGD-induced neuronal caspase-1 activation and mature IL-1β release.

Figure 5.

Methazolamide and melatonin inhibit the release of IL-1β and caspase-1 activation. Cell death was induced in PCNs by subjecting cells to OGD for 3 hours with or without 10 μmol/L methazolamide (A, C, and D) and 10 μmol/L melatonin (B, C, and D). Subsequently, conditioned media was collected and assayed for mature IL-1β release after the completion of OGD (A and B), or whole cells were extracted (C and D), and analyzed by Western blot (each of which contained 50 μg of protein) using antibodies to caspase–1 (C). Beta-actin was used as a loading control. This blot is representative of 3 independent experiments. Caspase-1 activity was quantified using a fluorogenic assay in lysed cells. Results are the average of at least 3 independent experiments. *P< 0.05, **P<0.001.

Methazolamide and Melatonin Decrease Cerebral Ischemia-Induced Injury

Just as it rescued cultured neurons from a variety of cell death stimuli, minocycline decreases the volume of the infarct produced by focal ischemia.30 We found that methazolamide and melatonin, like minocycline, forestall cell death attributable to the same stimuli H2O2 or NMDA, suggesting that they may be protective in cerebral ischemia. Indeed, methazolamide and melatonin-treated mice had significantly smaller infarcts after MCAO than mice injected with the vehicle (Figure 6A and 6B). Associated with a smaller infract, their postischemic behavior was less severely impaired (Figure 6A and 6C). The drugs were effective if administered either 1 hour before or 30 minutes after the onset of ischemia. We note that even though pretreatment and posttreatment resulted in similar protection as evaluated by TTC, pretreatment resulted in a greater degree of protection as assessed by behavior (Figure 6B and 6C). Considering that TTC is a gross marker of territorial infarction and does not distinguish functional versus dysfunctional brain that is alive, thus it is possible that even though the size of the injury is the same based on TTC criteria, there is a difference in the cerebral territory that is dysfunctional, but not dead depending whether the mice were pre or post treated with melatonin. These observations constitute the first report that methazolamide offers neuroprotection in an animal model of cerebral ischemia. They also confirm that melatonin is beneficial in animal models of cerebral ischemia, this time in mice rather than in rats.31,32

Figure 6.

Methazolamide and melatonin diminish damage from cerebral ischemia. Lesion size (A and B) and neuro-scores (C) were determined for mice injected with saline (controls), or methazolamide (20 mg/kg body weight), or melatonin (10 mg/kg body weight). Drugs were administered either 1 hour before or 30 minutes after MCAO. Each test and control group consisted of 7 to 14 mice (n=7 to 14). In all graphs, Data are presented as mean±SE, statistically significant effects are marked with * if P<0.05, and with ** if P<0.001. Brains were quickly removed, cut into coronal sections, and stained with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (A). In addition, lysates of brain tissue were resolved into cytosolic fractions for analysis by Western blotting (D and E). The protein samples were resolved on SDS/PAGE gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, probed with antibodies to cytochrome c or caspase-3, and reprobed with anti—β-actin. Western blots revealed changes in the cellular localization and degree of maturation of the respective target proteins (D and E). Densitometric scans of these gels allowed the signals from cytoplasmic cytochrome c and activated caspase-3 to be compared to that from β-actin. Each test group consisted of 3 to 5 mice. Again, * indicates that P<0.05 and ** that P<0.001. White bars correspond to brain samples from animals that neither underwent MCAO nor received any test drug. Black bars correspond to samples from saline-injected animals that did undergo MCAO. Grey and light grey bars correspond to samples from test animals, ie, those that were both treated with an experimental drug and underwent MCAO.

Like mitochondrial dysfunction, the resulting caspase-mediated cell death pathways are important in a broad spectrum of acute and chronic neurodegenerative diseases.2,4,5,15 In particular, cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation are observed in brains of mice that have recently suffered ischemic damage.15,33,34 Because methazolamide and melatonin are neuroprotective in animal models of stroke, we evaluated whether they diminish cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation stimulated by acute insult. As observed in cultured cells challenged with OGD, methazolamide and melatonin reduced cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation in ischemic tissue in vivo (Figure 6D and 6E).

Discussion

Consequences of cerebral ischemia result in significant human morbidity and mortality. Despite great efforts to identify protective drugs for cerebral ischemia, discovery of an effective agent remains elusive. Failure might be in part the result of selection of inappropriate targets or the inappropriate executions and expectations of clinical trials. Given the prominent role of mitochondria both in generating energy required for cell survival and in triggering cell death pathways, we hypothesize that identifying drugs that target mitochondrial pathways may be broadly neuroprotective. Using an isolated/cell-free mitochondrial screen, we have identified a set of drugs that inhibit cytochrome c release in the isolated organelle.6 We demonstrate that most but not all the cytochrome c release inhibitors are protective in a number of neuronal cell death models. The 2 drugs selected for further evaluation, methazolamide and melatonin, not only inhibited cytochrome c release and cell death, but also inhibited the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, caspase-3 activation, caspase-1 activation, and IL-1β processing associated with exposure to a cell death stimulus.

Drug-mediated preservation of membrane potential under circumstances that otherwise would lead to cellular demise point to the ability of these agents to protect/enhance mithochondrial function. Therefore the drugs not only inhibit the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c/AIF with the subsequent activation of cell death pathways, but concomitantly improve mitochondrial function and as a result cellular health. Given that AIF is an important mediator of caspase-independent cell death pathways, our observation with methazolamide and melatonin inhibiting AIF release represents the first report demonstrating the ability to inhibit both caspase-dependent (cytochrome c) and caspase-independent (AIF) mitochondrial cell death pathways.

There are at least 2 major pathways for cytochrome c release in both in vitro and in vivo. These are the mPT and the proapoptotic pathways induced by Bcl-2 family members such as Bid/Bax/Bak/bad, etc. Given that these drugs do not act at the mPT, it is most likely that they act by a bcl-2 family—modulated pathway. Further refinement of the molecular target is a goal of ongoing and future research.

We demonstrate that these 2 drugs are protective in an in vivo experimental model of cerebral ischemia. This is the first demonstration that the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor methazolamide is neuroprotective in cerebral ischemia. The exogenous administration of methazolamide in the experimental stroke model reduced infarct volume, improved the neurological score, and lowered cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation. Even though melatonin has been previously universally demonstrated to be neuroprotective in experimental models of cerebral ischemia in several species including mice,17 adult18 and neonatal rats,19 gerbils,20 and cats,21 the mechanisms of action are not known understood. Hence we extend this finding by demonstrating not only efficacy in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia but also inhibition of cytochrome c release as a target of melatonin-mediated neuroprotection. An additional new finding is the demonstration that melatonin inhibits hypoxia-induced caspase-1 activation. From a mechanistic and drug development standpoint, we demonstrate that a mitochondrial-based drug screen can identify effective neuroprotective drugs. Therefore, this work provides evidence of the efficacy of a mitochondrial screen in identifying drugs with neuroprotective properties. Given that the drugs were identified as inhibitors of cytochrome c release, this work also provides further support for the key role of this biological event in neurodegeneration. At the physiological level, it validates targeting the molecular process as a rational approach to the design of therapies for cerebral ischemia. We demonstrate that the mitochondrial screen is efficacious at selecting protective drugs not only for acute but also for chronic neurodegeneration. It is important to note that these drugs are safe, have been in human use for many years, and cross the blood— brain barrier, making them attractive agents for further human evaluation.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (to R.M.F., X.W.); the Huntington’s Disease Society of America (to R.M.F.); Departmental funds (to R.M.F.); the Hereditary Disease Foundation (to X.W., B.S.K.) and New York State CORE grants (to I.G.S., and B.S.K.).

Footnotes

Disclosures None.

References

- 1.Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Alnemri ES, Wang X. Cytochrome c and datp-dependent formation of apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell. 1997;91:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan PH. Mitochondria and neuronal death/survival signaling pathways in cerebral ischemia. Neurochem Res. 2004;29:1943–1949. doi: 10.1007/s11064-004-6869-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Namura S, Nagata I, Takami S, Masayasu H, Kikuchi H. Ebselen reduces cytochrome c release from mitochondria and subsequent DNA fragmen-tation after transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Stroke. 2001;32:1906–1911. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.8.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang WH, Wang X, Narayanan M, Zhang Y, Huo C, Reed JC, Friedlander RM. Fundamental role of the rip2/caspase-1 pathway in hypoxia and ischemia-induced neuronal cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:16012–16017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2534856100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Zhu S, Drozda M, Zhang W, Stavrovskaya IG, Cattaneo E, Ferrante RJ, Kristal BS, Friedlander RM. Minocycline inhibits caspase-independent and -dependent mitochondrial cell death pathways in models of Huntington’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10483–10487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832501100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, Zhu S, Pei Z, Drozda M, Stavrovskaya IG, Del Signore SJ, Cormier K, Shimony EM, Wang H, Ferrante RJ, Kristal BS, Friedlander RM. Inhibitors of cytochrome c release with therapeutic potential for Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9473–9485. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1867-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang WH, Wang H, Wang X, Narayanan MV, Stavrovskaya IG, Kristal BS, Friedlander RM. Nortriptyline protects mitochondria and reduces cerebral ischemia/hypoxia injury. Stroke. 2008;39:455–462. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.496810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu S, Stavrovskaya IG, Drozda M, Kim BY, Ona V, Li M, Sarang S, Liu AS, Hartley DM, Wu du C, Gullans S, Ferrante RJ, Przedborski S, Kristal BS, Friedlander RM. Minocycline inhibits cytochrome c release and delays progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. Nature. 2002;417:74–78. doi: 10.1038/417074a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baranov SV, Stavrovskaya IG, Brown AM, Tyryshkin AM, Kristal BS. Kinetic model for Ca2+-induced permeability transition in energized liver mitochondria discriminates between inhibitor mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:665–676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703484200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedlander RM, Gagliardini V, Hara H, Fink KB, Li W, MacDonald G, Fishman MC, Greenberg AH, Moskowitz MA, Yuan J. Expression of a dominant negative mutant of interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme in transgenic mice prevents neuronal cell death induced by trophic factor withdrawal and ischemic brain injury. J Exp Med. 1997;185:933–940. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plesnila N, Zinkel S, Le DA, Amin-Hanjani S, Wu Y, Qiu J, Chiarugi A, Thomas SS, Kohane DS, Korsmeyer SJ, Moskowitz MA. Bid mediates neuronal cell death after oxygen/ glucose deprivation and focal cerebral ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15318–15323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261323298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarang SS, Yoshida T, Cadet R, Valeras AS, Jensen RV, Gullans SR. Discovery of molecular mechanisms of neuroprotection using cell-based bioassays and oligonucleotide arrays. Physiol Genomics. 2002;11:45–52. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00064.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tikka T, Fiebich BL, Goldsteins G, Keinanen R, Koistinaho J. Mino-cycline, a tetracycline derivative, is neuroprotective against excitotoxicity by inhibiting activation and proliferation of microglia. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2580–2588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02580.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mejia RO Sanchez, Ona VO, Li M, Friedlander RM. Minocycline reduces traumatic brain injury-mediated caspase-1 activation, tissue damage, and neurological dysfunction. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:1393–1399. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200106000-00051. discussion 1399-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedlander RM. Apoptosis and caspases in neurodegenerative diseases. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1365–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cazevieille C, Safa R, Osborne NN. Melatonin protects primary cultures of rat cortical neurones from NMDA excitotoxicity and hypoxia/reoxy-genation. Brain Res. 1997;768:120–124. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00611-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen HY, Chen TY, Lee MY, Chen ST, Hsu YS, Kuo YL, Chang GL, Wu TS, Lee EJ. Melatonin decreases neurovascular oxidative/nitrosative damage and protects against early increases in the blood-brain barrier permeability after transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Pineal Res. 2006;41:175–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh PO. Melatonin attenuates the focal cerebral ischemic injury by inhibiting the dissociation of pbad from 14-3 3. J Pineal Res. 2008;44:101–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carloni S, Perrone S, Buonocore G, Longini M, Proietti F, Balduini W. Melatonin protects from the long-term consequences of a neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in rats. J Pineal Res. 2008;44:157–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rennie K, de Butte M, Frechette M, Pappas BA. Chronic and acute melatonin effects in gerbil global forebrain ischemia: Long-term neural and behavioral outcome. J Pineal Res. 2008;44:149–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letechipia-Vallejo G, Gonzalez-Burgos I, Cervantes M. Neuroprotective effect of melatonin on brain damage induced by acute global cerebral ischemia in cats. Arch Med Res. 2001;32:186–192. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(01)00268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I, Snow BE, Brothers GM, Mangion J, Jacotot E, Costantini P, Loeffler M, Larochette N, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, Siderovski DP, Penninger JM, Kroemer G. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 1999;397:441–446. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang LK, Putcha GV, Deshmukh M, Johnson EM. Mitochondrial involvement in the point of no return in neuronal apoptosis. Biochimie. 2002;84:223–231. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zoratti M, Szabo I, De Marchi U. Mitochondrial permeability transitions: How many doors to the house? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1706:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crompton M, Virji S, Doyle V, Johnson N, Ward JM. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Biochem Soc Symp. 1999;66:167–179. doi: 10.1042/bss0660167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stavrovskaya IG, Narayanan MV, Zhang W, Krasnikov BF, Heemskerk J, Young SS, Blass JP, Brown AM, Beal MF, Friedlander RM, Kristal BS. Clinically approved heterocyclics act on a mitochondrial target and reduce stroke-induced pathology. J Exp Med. 2004;200:211–222. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li P, Allen H, Banerjee S, Franklin S, Herzog L, Johnston C, McDowell J, Paskind M, Rodman L, Salfeld J, et al. Mice deficient in Il-1 beta-converting enzyme are defective in production of mature il-1 beta and resistant to endotoxic shock. Cell. 1995;80:401–411. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedlander RM, Gagliardini V, Rotello RJ, Yuan J. Functional role of interleukin 1 beta (Il-1 beta) in Il-1 beta-converting enzyme-mediated apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1996;184:717–724. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, Narayanan M, Bruey JM, Rigamonti D, Cattaneo E, Reed JC, Friedlander RM. Protective role of cop in rip2/caspase-1/caspase-4-mediated HeLa cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:742–754. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yrjanheikki J, Tikka T, Keinanen R, Goldsteins G, Chan PH, Koistinaho J. A tetracycline derivative, minocycline, reduces inflammation and protects against focal cerebral ischemia with a wide therapeutic window. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13496–13500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pei Z, Pang SF, Cheung RT. Administration of melatonin after onset of ischemia reduces the volume of cerebral infarction in a rat middle cerebral artery occlusion stroke model. Stroke. 2003;34:770–775. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000057460.14810.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reiter RJ, Sainz RM, Lopez-Burillo S, Mayo JC, Manchester LC, Tan DX. Melatonin ameliorates neurologic damage and neurophysiologic deficits in experimental models of stroke. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;993:35–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07509.x. discussion 48-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholls DG. Mitochondrial function and dysfunction in the cell: Its relevance to aging and aging-related disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:1372–1381. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim GW, Sugawara T, Chan PH. Involvement of oxidative stress and caspase-3 in cortical infarction after photothrombotic ischemia in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1690–1701. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200012000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]