Abstract

Activation of resting T lymphocytes initiates differentiation into mature effector cells over 3–7 days. The chemokine CCL5 (RANTES) and its major transcriptional regulator, Krüppel-like factor 13 (KLF13), are expressed late (3–5 days) after activation in T lymphocytes. Using yeast two-hybrid screening of a human thymus cDNA library, PRP4, a serine/threonine protein kinase, was identified as a KLF13-binding protein. Specific interaction of KLF13 and PRP4 was confirmed by reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation. PRP4 is expressed in PHA-stimulated human T lymphocytes from days 1 and 7 with a peak at day 3. Using an in vitro kinase assay, it was found that PRP4 phosphorylates KLF13. Furthermore, although phosphorylation of KLF13 by PRP4 results in lower binding affinity to the A/B site of the CCL5 promoter, coexpression of PRP4 and KLF13 increases nuclear localization of KLF13 and CCL5 transcription. Finally, knock-down of PRP4 by small interfering RNA markedly decreases CCL5 expression in T lymphocytes. Thus, PRP4-mediated phosphorylation of KLF13 plays a role in the regulation of CCL5 expression in T lymphocytes.

A fundamental question in inflammatory disease is how immune cells move from the bloodstream to sites of disease. This process is central to the development of a variety of acute and chronic immune-mediated diseases. Critical components in this process are chemokines that direct the movement and infiltration of specific subsets of inflammatory cells to the site of inflammation (1). This family of small proteins also plays an important role in the control of leukocyte recruitment, activation, and effector function, as well as hemopoiesis, the modulation of angiogenesis, and aspects of adaptive immunity (2-6). CCL5, a member of the C-C chemokine family, is a potent chemoattractant of T lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, and NK cells (7-11). CCL5 also activates T lymphocytes, causes degranulation of basophils, and mediates a respiratory burst in eosinophils (12-14). Collectively, these functions implicate CCL5 as an important mediator of both acute and chronic inflammation. The chemokine receptor CCR5, which binds CCL5 and the related chemokines MIP-1α and MIP-1β, serves as a coreceptor for HIV to enter target cells (15-19). Thus, CCL5 has become an important therapeutic target for immune-mediated diseases. The development of anti-inflammatory agents capable of blocking CCL5 expression may inhibit the generation of cellular infiltrate in auto-immunity and transplant rejection. In contrast, inducing CCL5 expression may be therapeutic for cancer and AIDS.

CCL5 is ubiquitously expressed in a variety of tissues under different conditions (20-23). In fibroblasts, epithelial cells, and monocytes/macrophages, the expression of CCL5 is elevated within hours of stimulation and is regulated by NF-κB (24, 25). In contrast, in T lymphocytes, the induction of CCL5 occurs 3–5 days after activation (26) and is regulated by a complex of proteins recruited by Krüppel-like factor 13 (KLF13)3 (27, 28). These late kinetics of expression help to amplify the immune response in both time and space, and are consistent with the late expression of other genes involved in T cell effector function including perforin, granulysin, and granzymes A and B. KLF13 binds to the CTCCC element of the human CCL5 promoter present in the A/B site (27). Silencing of KLF13 expression in human T lymphocytes with small interfering RNA (siRNA) decreases the expression of CCL5 mRNA and protein (28). Although KLF13 mRNA levels are similar in resting and activated T lymphocytes, KLF13 protein is only expressed in actively proliferating and differentiating T lymphocytes (translational regulation), coincident with CCL5 gene expression (29). Interestingly, KLF13 is highly phosphorylated in activated T lymphocytes (27), suggesting that, like many transcription factors, its activity is regulated by kinases. To identify binding partners and potential regulators of KLF13 function, yeast two-hybrid screening was performed in the present study. PRP4 kinase, a member of the MAPK family, was found to bind KLF13 and to regulate CCL5 expression in human T lymphocytes.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

RFLAT-1 (C-19) Ab for supershifting KLF13 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-GFP and Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-mouse IgG2b(γ2b) were purchased from Molecular Probes. Anti-hemagglutinin (HA) mouse mAb (clone 12CA5) was purchased from Roche Diagnostic Systems. Anti-V5 mouse mAb was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-α-actinin was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology. Rabbit polyclonal antisera to KLF13 was produced as described previously (27). Rabbit polyclonal antisera to PRP4 was produced by immunizing rabbits with synthetic peptides LKKLNDADPDDKFHC (residues 736–750) and CQRLPEDQRKKVHQLK (residues 962–977) conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Washington Biotechnology).

Plasmid constructs

pGL3-RP-luc was constructed by inserting −195 to +54 bp of the CCL5 promoter into the pGL3-basic vector (Promega). pSOS-KLF13 construct was obtained by subcloning the PCR-amplified full-length KLF13 into NcoI/SacI sites of the bait vector pSOS (Stratagene). pME-HA-PRP4, which contains full-length PRP4, was a gift from Dr. M. Hagiwara (Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan). pcDNA3.1-KLF13 and pcDNA3.1/CT-GFP-KLF13 constructs were obtained by subcloning a PCR product encoding full-length human KLF13 cDNA into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1− and pcDNA3.1/CT-GFP (Invitrogen Life Technologies), respectively. pcDNA3.1/V5-His-Nemo-like kinase (NLK) was constructed by subcloning the full-length human NLK cDNA into pcDNA3.1/V5-His vector (Invitrogen Life Technologies). pET28a-KLF13 and pET28a-KLF13 (1–263), used for expression of full-length or aa 264–288 truncated recombinant KLF13, were obtained by subcloning the corresponding PCR-amplified cDNA into pET28a+ vector (Invitrogen Life Technologies).

Yeast two-hybrid analysis

The CytoTrap two-hybrid system (Stratagene) was used to identify proteins that bind to KLF13 using pSOS-KLF13 as the bait construct. This construct was cotransfected into a mutant yeast strain cdc25Hα with a CytoTrap XR Human Thymus cDNA Library cloned in pMyr vector following the manufacturer's protocol. Plasmids were extracted from putative positive colonies and transformed into Escherichia coli to be further analyzed by DNA sequencing. Only peptide sequences that were in frame in pMyr were considered for further validation.

Cell culture, transfection, and luciferase assays

Human peripheral blood T lymphocytes were isolated from leukopacs (Stanford Blood Bank) by negative selection (RosetteSep) according to the manufacturer's protocol (StemCell Technologies). T lymphocytes and COS7 cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in either RPMI 1640 medium (Irvine Scientific) or DMEM (Invitrogen Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (HyClone), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin, respectively. T lymphocytes were stimulated with 5 μg/ml PHA for up to 7 days. Transient transfection of COS7 cells was performed using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics Systems) according to the manufacturer's recommendation. For luciferase reporter assays, COS7 cells (2.5 × 105) were transfected with pGL3-RP-luc (0.6 μg) plus pcDNA3.1-KLF13 (0.3 μg) and/or pME-HA-PRP4 (0.3 μg). Corresponding empty vectors were used to keep the total amount of DNA constant. A pRL-TK plasmid (20 ng; Promega) encoding a Renilla luciferase gene was included as an internal control. The cells were harvested and lysed 36-h post-transfection, and luciferase activity was determined using a Dual Luciferase Assay Kit (Promega). Firefly luciferase activities were normalized to Renilla activities to account for differences in transfection efficiency.

Immunoprecipitation and kinase assay

Transfected COS7 cells were lysed in buffer A containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 420 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 25% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitors. Lysates were clarified at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Immunoprecipitations from cell lysates were conducted using corresponding Ab along with protein A/G agarose beads. After incubating for 16 h at 4°C, immune complexes were collected by centrifugation and then washed two times with lysis buffer and two times with PBS. For kinase assays, the immunoprecipitants were washed one more time with kinase buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mM DTT). In the kinase reaction, His-tagged full-length or aa 264–288-truncated KLF13 was used as substrate. Purification of recombinant KLF13 protein through a Ni+ column was described previously (27). The immunocomplexes were incubated at 30°C in kinase buffer supplemented with 1 mM ATP, 1 μCi [γ-32P]ATP, and 1 μg of recombinant KLF13 in a volume of 30 μl for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer and the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Phosphorylated KLF13 was visualized by autoradiography. For EMSA, phosphorylated recombinant KLF13 was made using cold ATP instead of [γ-32P]ATP in the kinase reaction.

Northern blot

Total RNA was extracted from human T lymphocytes using the RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). Twenty micrograms of total RNA was used for Northern blotting as previously described (30). The membrane was hybridized with 32P-labeled PRP4 cDNA, stripped, and then reprobed with 32P-labeled 28S rRNA antisense oligonucleotide to confirm equal loading and transfer. Relative quantification was performed using densitometry.

Western blot

T lymphocytes were lysed in buffer A as described above. T cell lysates or immunoprecipitants from transfected COS7 cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE and the membrane was hybridized with Abs against KLF13 or PRP4. ECL Western blotting detection reagents were used for detection (Amersham Biosciences). Loading and transfer efficiency were confirmed by blotting with a mouse Ab against α-actinin.

EMSA

A double-stranded oligonucleotide corresponding to the A/B site of the CCL5 promoter was used as a probe for EMSA as previously described (27). The labeled probe (20,000 cpm) was incubated with 1 μg of recombinant KLF13 from the kinase reaction, 1.5 μg of poly(dI:dC), 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 80 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol for 20 min at room temperature. EMSA was also performed using immunoprecipitants from COS7 cells transfected with either empty vector (vector) or pME-HA-PRP4 (PRP4) in the absence of KLF13 as additional negative controls. For supershift assays, 2 μg of Ab was added to the binding mixture. DNA-protein complexes were analyzed on a 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5 × Tris-borate-EDTA buffer.

Cellular localization experiments

To visualize the intracellular localization of KLF13 and PRP4, COS7 cells (2 × 104) grown on tissue culture glass slides were transfected with pcDNA3.1-GFP-KLF13 (0.2 μg) and pME-HA-PRP4 (0.2 μg), either alone or in combination using FuGene 6 transfection reagent. Corresponding empty vector was used as a control. After 24 h, the transfected cells were fixed and permeabilized. KLF13 and PRP4 were detected by immunofluorescence as described by Kojima et al. (31) using Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-GFP (1/2000 dilution) for GFP-tagged KLF13 and anti-HA mouse mAb (1/2, 000 dilution) for HA-tagged PRP4. Secondary Ab conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-mouse IgG2b(γ2b) (1/1,000; Invitrogen Life Technologies) was used for double labeling of HA-tagged PRP4. The nuclei were visualized using Hoechst 33342 (1/10,000; Invitrogen Life Technologies) staining. The cellular localization of KLF13 and PRP4 proteins was monitored using an immunofluorescence microscope.

siRNA and real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Knock-down of PRP4 mRNA was achieved using double-stranded siRNA oligonucleotides obtained from Qiagen. Nonsilencing siRNA (5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUdTdT-3′), which has no homology to any known mammalian gene, was used as a negative control. A total of 1.5 μg of siRNA was nucleofected into 5 × 106 freshly isolated T lymphocytes using the Human T Cell Nucleofector Kit per the manufacturer's instruction (Amaxa). PHA was added 4 h after nucleofection to achieve a final concentration of 5 μg/ml. Cells were incubated for an additional 30 h and harvested for both nuclear extract preparation and RNA isolation. To measure gene expression, cDNA was made from total RNA using Superscript II with random hexamers (Invitrogen Life Technologies) for use in RT-qPCR with the GeneAmp 7900 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). NLK primers were used in RT-qPCR to determine the specificity of PRP4 siRNAs, and β-glucuronidase (GUS) was used for normalizing RT-qPCR results. Primers for CCL5 and NLK were synthesized by Elim Biopharmaceuticals, and primers for PRP4 and GUS were purchased from Applied Biosystems. All RT-qPCR was performed in triplicate using either SYBR green or TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The expression level of a gene in a given sample was represented as 2−ΔΔCt, where ΔΔCt = (ΔCt(silencing)) − (ΔCt(non-silencing)) and ΔCt = (Ct(sample) − Ct(Gus)). Values represent the fold change of target gene expression from PRP4 siRNA-transfected vs nonsilencing siRNA-transfected primary T lymphocytes.

ELISA

CCL5 protein levels were measured in the culture supernatant using the Endogen Human RANTES ELISA Kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Results

PRP4 binds KLF13 in human thymocytes

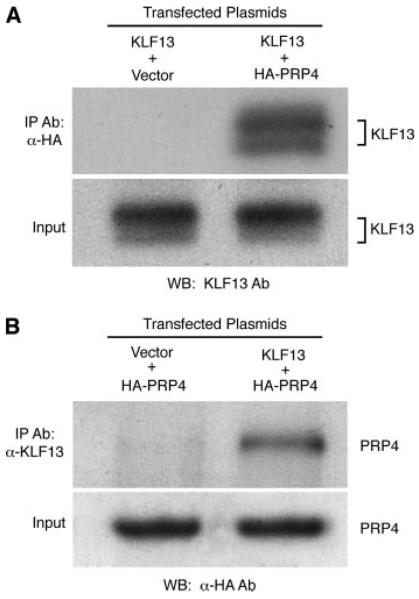

The CytoTrap yeast two-hybrid system was used to screen a human thymus library for proteins that bind to KLF13. Approximately 2 × 106 transformants were screened with a pSOS-KLF13 construct, and 19 putative positive clones were identified. Comparison of cDNA sequences of the clones with the GenBank database revealed that one of them is the human homolog of the yeast serine-threonine kinase PRP4. To further confirm the physical interaction between KLF13 and PRP4, reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed. COS7 cells were cotransfected with pME-HA-PRP4 construct and pcDNA3.1-KLF13. Replacement of one expression plasmid with its corresponding empty vector was used to show specificity of coimmunoprecipitation. Only HA-PRP4-transfected COS7 lysates immunoprecipitated with an anti-HA Ab against tagged PRP4 pulled down KLF13 (Fig. 1A), while the reciprocal experiment using a KLF13 Ab pulled down PRP4 (Fig. 1B). These data confirm that KLF13 binds PRP4.

FIGURE 1.

KLF13 interacts with PRP4. A, Lysates of COS7 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-KLF13 (KLF13) along with either pME-HA (vector) or pME-HA-PRP4 (HA-PRP4) were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA mouse mAb. B, Lysates of COS7 cells transfected with HA-PRP4, along with either pcDNA3.1 (vector) or KLF13, were immunoprecipitated with anti-KLF13 antisera. Bound proteins were analyzed by Western blot using the indicated Abs. Equal input of KLF13 (A) and PRP4 (B) was confirmed by Western blot of unprecipitated cell lysates.

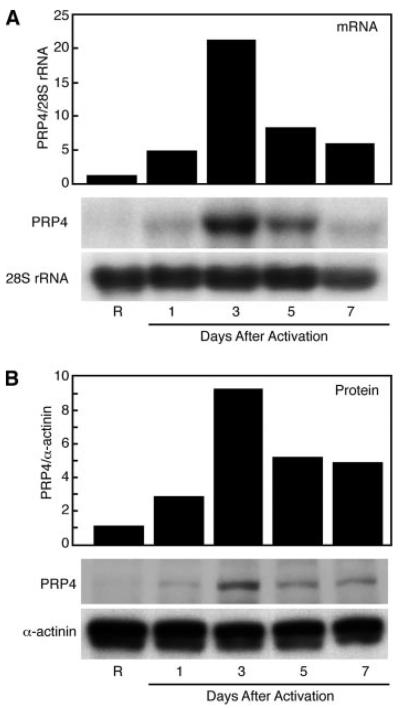

PRP4, a MAPK, is expressed in T lymphocytes

T lymphocytes were isolated from peripheral blood and activated with the mitogen PHA. PRP4 mRNA and protein were measured in resting T lymphocytes and through 7 days after activation. Low levels of PRP4 mRNA were detected by Northern blot in resting T lymphocytes (Fig. 2A). mRNA levels increased 5-fold 1 day after the activation of T lymphocytes with PHA and, by day 3, had increased ∼20-fold. PRP4 mRNA decreased on day 5 and, by day 7, PRP4 mRNA dropped to the same level seen on day 1. PRP4-specific rabbit antisera were generated to monitor PRP4 protein expression during T lymphocyte activation by Western blot (Fig. 2B). Parallel to the mRNA results, only trace amounts of PRP4 protein were present in resting T lymphocytes. PRP4 protein increased 1 day after activation and continued to increase with a peak of 9-fold induction observed by day 3. Protein levels decreased on days 5 and 7, consistent with mRNA expression. Thus, PRP4 kinase is expressed in human T lymphocytes and displays an activation kinetic peaking in expression at day 3.

FIGURE 2.

Expression of PRP4 in resting and PHA-activated T lymphocytes. A, Northern blot of PRP4 mRNA. Blots were sequentially hybridized with 32P-labeled human PRP4 cDNA and 28S rRNA oligonucleotide probe. Bar graph, Quantification of the relative abundance of PRP4 mRNA normalized to 28S rRNA. B, Western blot of PRP4 protein. PRP4-specific antisera were used to detect protein, whereas α-actinin Ab was used as an internal control. Bar graph, Quantification of the amount of PRP4 protein normalized to α-actinin. Results are representative of four similar experiments.

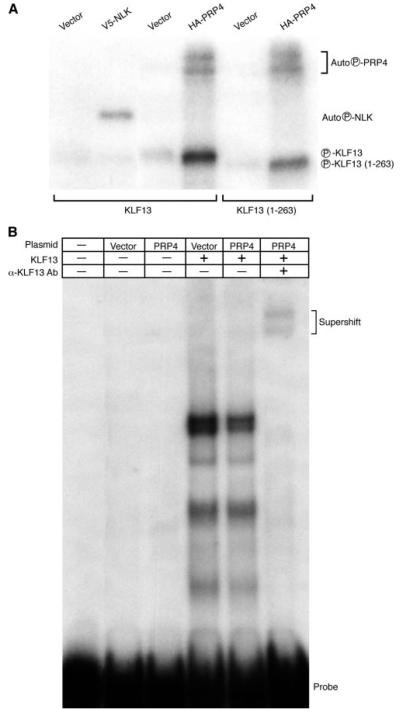

PRP4 phosphorylates KLF13, decreasing its binding affinity to the CCL5 promoter A/B site

KLF13 is the major transcription factor regulating CCL5 expression in T lymphocytes (27, 28). KLF13 is expressed late (days 3–5) after T lymphocyte activation, is rapidly phosphorylated, and is present in both the nucleus and the cytosol (27, 32). Because the protein expression patterns of KLF13 and PRP4 are similar, we tested whether PRP4 and NLK, another MAPK family member, could phosphorylate KLF13 (Fig. 3A). The immunoprecipitants derived from PRP4- or NLK-overexpressing COS7 cells were used to phosphorylate recombinant KLF13 in a kinase assay, with immunoprecipitants from corresponding vector-transfected cells used as a negative control. Under these conditions, immunoprecipitated PRP4 phosphorylated both itself and KLF13 (Fig. 3A, lane 4). In contrast, immunoprecipitated NLK phosphorylated itself, but not KLF13 (Fig. 3A, lane 2). We previously found that NLK was recruited to the CCL5 promoter by KLF13 and subsequently phosphorylates serine 10 of histone H3 upon T lymphocyte activation (28). These results suggest that PRP4 and NLK regulate CCL5 expression by phosphorylating different target proteins. Immunoprecipitated PRP4 also phosphorylated KLF13 (1–263) that has 25 aa deleted from the C terminus (Fig. 3A, lane 6). However, phosphorylation was less robust, suggesting that KLF13 may contain multiple PRP4 phosphorylation sites, with one or more sites in the truncated region.

FIGURE 3.

PRP4 phosphorylates KLF13 and disrupts the binding of KLF13 to the CCL5 promoter A/B site. COS7 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1/V5-His-NLK (V5-NLK), pME-HA-PRP4 (HA-PRP4), or corresponding empty vectors, as indicated, and immunoprecipitated with anti-HA or anti-V5 Ab. A, Recombinant KLF13 or KLF13 (1–263) were phosphorylated in a kinase reaction in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP with either vector, V5-NLK, or HA-PRP4 immunoprecipitants, as indicated. and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. B, Immunoprecipitants from COS7 cells transfected with vector or HA-PRP4 were used to phosphorylate recombinant KLF13 in the presence of cold ATP, and the products were subjected to EMSA. Kinase reactions lacking KLF13 substrate were also analyzed as controls. KLF13-specific Ab was used to supershift.

To test whether the phosphorylation of KLF13 by PRP4 affects its interaction with the CCL5 promoter, EMSA was performed using a γ-32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide derived from the A/B region of the CCL5 promoter. Full-length recombinant KLF13 was phosphorylated by immunoprecipitated PRP4 obtained from transfected COS7 cell lysate using unlabeled ATP, with immunoprecipitant from vector-transfected COS7 cell lysate serving as control. An upper doublet and three lower bands were observed. Although the upper doublet most likely corresponds to the full-length KLF13 bound to probe, the lower bands may result from the degradation of the KLF13 substrate during the kinase reaction. All of these DNA-protein complexes were supershifted upon the addition of anti-KLF13 Ab (Fig. 3B), but not with anti-p50 Ab (data not shown), indicating the specificity of binding. In the presence of PRP4, there is a ∼50% decrease in KLF13 bound to the CCL5 promoter A/B site probe (Fig. 3B). Thus, phosphorylation of KLF13 by PRP4 results in lower binding affinity to the CCL5 promoter compared with nonphosphorylated KLF13.

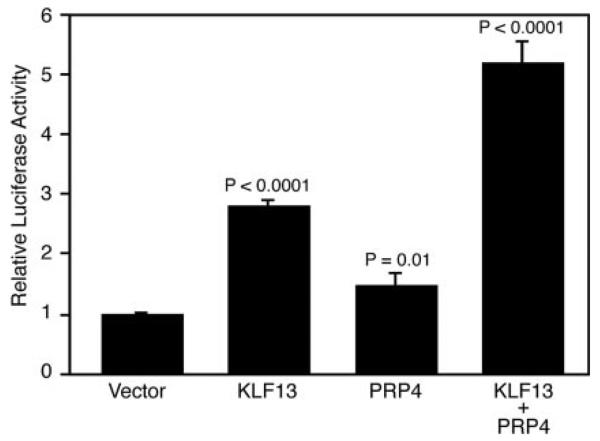

KLF13 and PRP4 synergistically regulate CCL5 expression

Reporter gene assays were performed to examine the effect of PRP4 on CCL5 transcription (Fig. 4). The CCL5 promoter luciferase reporter construct pGL3-RP was transfected into COS7 cells along with KLF13 and/or PRP4 expression constructs. Compared with vector control, expression of KLF13 caused a 2.8-fold induction (p < 0.0001) in CCL5 reporter gene activity, while expression of PRP4 caused a 1.4-fold increase (p = 0.01). However, coexpression of KLF13 and PRP4 resulted in a 5.2-fold increase (p < 0.0001) in CCL5 promoter activity. Of note, we detected endogenous PRP4 in COS7 cells (data not shown), explaining the modest increase in CCL5 promoter activity in the presence of transfected PRP4. These results indicate that PRP4 synergizes with KLF13 to regulate CCL5 expression in vitro.

FIGURE 4.

PRP4 and KLF13 synergize to regulate CCL5 transcription. pGL3-RP-luc and pRL-TK were cotransfected with pcDNA3.1-KLF13 (KLF13) and/or pME-HA-PRP4 (PRP4) into COS7 cells. Results are shown as relative luciferase activity with the basal luciferase activity (vector) set to 1. The data are expressed as the average ± SD from three independent experiments. The p values compared with vector control are indicated.

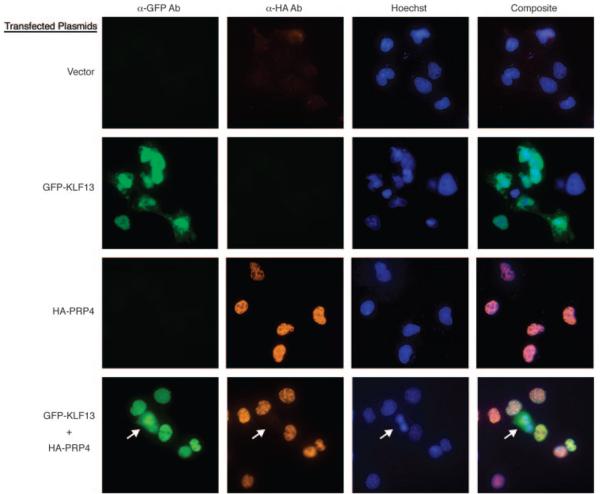

PRP4 increases the nuclear localization of KLF13

To further investigate the role of PRP4 in regulating CCL5 expression, the effect of PRP4 on intracellular localization of KLF13 was assessed. COS7 cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors corresponding to empty vector, GFP-KLF13, HA-PRP4, or a combination of GFP-KLF13 and HA-PRP4. No signal was detected when cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1, and only a small amount of background signal was observed throughout the cell following transfection of the pME-HA vector (Fig. 5). In the absence of PRP4, overexpressed KLF13 protein was detected in the nuclear compartment of all KLF13-transfected COS7 cells, while 45–50% of these cells also had KLF13 in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5, GFP-KLF13/α-GFPAb). In contrast, when KLF13 was coexpressed with PRP4, KLF13 resided almost exclusively in the nucleus, indicating that PRP4 regulates the nuclear translocation of KLF13 (Fig. 5, GFP-KLF13 + HA-PRP4/α-GFPAb). The arrows in the frames transfected with GFP-KLF13 + HA-PRP4 (Fig. 5) mark a single cell that expresses KLF13, but not PRP4. It is evident that, in the absence of PRP4, overexpressed KLF13 is distributed both in the nuclei and cytoplasm of the cell. In contrast, overexpressed KLF13 resides exclusively in the nuclei of the other cells in the same field that is coexpressing both KLF13 and PRP4, supporting the role of PRP4 in KLF13 nuclear translocation. Overexpressed PRP4 is predominantly expressed in the nucleus of the cell, regardless of the presence or absence of overexpressed KLF13 (Fig. 5, HA-PRP4/αHAAb). Frames of Fig. 5 in each row shows nuclei visualized by Hoechst staining. Composite was generated by merging images from frames 1–3 (Fig. 5) in each row to better visualize colocalization.

FIGURE 5.

PRP4 increases the nuclear localization of KLF13. COS7 cells were transfected with either pcDN A3.1/CT-GFP-KLF13 (GFP-KLF13), or pME-HA-PRP4 (HA-PRP4), or in combination (GFP-KLF13 + HAPRP4). Cells transfected with corresponding amounts of pcDNA3.1 and pME-HA were used as negative control (Vector). After 24 h, GFP-KLF13 and HA-PRP4 were stained with anti-GFP Ab and anti-HA Ab, respectively, and detected using immunofluorescence microscopy. Nuclei were visualized by Hoechst staining. Composite shows the overlapped image of anti-GFP Ab, anti-HA Ab, and Hoechst stained images. Arrow, Cell expressing only GFP-KLF13 that shows a different pattern of cellular distribution compared with other cells in this field that coexpress both GFP-KLF13 and HA-PRP4.

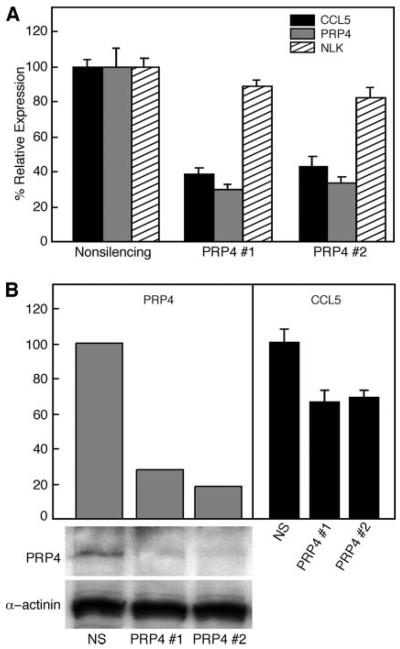

Knock-down of PRP4 decreases CCL5 expression in human T lymphocytes

To confirm the role of PRP4 in regulating CCL5 expression in T lymphocytes, two sets of PRP4-specific siRNAs were nucleofected into resting human T lymphocytes. The cells were then stimulated with PHA, and the expression of CCL5 was measured after 30 h using RT-qPCR and ELISA. PRP4 mRNA (Fig. 6A) and protein (Fig. 6B) were suppressed >65% by both sets of siRNA. In contrast, PRP4-specific siRNAs caused only 10–15% suppression of NLK mRNA expression (Fig. 6A), demonstrating the specificity of the siRNAs. Moreover, both sets of PRP4 siRNA repressed CCL5 expression, with ∼55–60% reduction in mRNA transcription and 30–35% reduction in protein expression (Fig. 6). Thus, PRP4 regulates CCL5 expression in T lymphocytes.

FIGURE 6.

Knock-down of PRP4 reduces CCL5 expression in T lymphocytes. A, Levels of CCL5, PRP4, and NLK mRNA after nucleofection of nonsilencing and PRP4 (1 and 2) siRNAs into resting human T lymphocytes followed by 30 h of PHA activation. Average ± SD of three experiments are shown. B, Protein levels of PRP4 and CCL5 in human T lymphocytes after treatment with nonsilencing or PRP4 siRNAs. Left, Western blot analysis of PRP4 protein. PRP4-specific antisera were used to determine the amounts of protein, whereas α-actinin Ab was used to normalize for protein loading. The graph shows the ratio of PRP4:α-actinin expression. Right: CCL5 in culture supernatants measured by ELISA. Data represent the mean ± SD of three triplicates.

Discussion

KLF13 is the major transcription factor that positively regulates CCL5 expression in activated T lymphocytes (27). We previously reported that KLF13 protein is expressed in the adult spleen and lung, but not in liver, brain, kidney, heart, or reproductive organs, and showed that KLF13 is translationally regulated through its 5′-untranslated region (29). In addition, KLF13 is highly phosphorylated in activated T lymphocytes, suggesting that its activity is regulated by posttranslational modification. In this study, we show that PRP4, a MAPK family member, phosphorylates KLF13 and plays an important role in the regulation of CCL5 expression in human T lymphocytes.

PRP4, originally isolated from the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, is involved in pre-mRNA splicing (33, 34). The human homolog of PRP4 is ubiquitously expressed in multiple tissues (31), including spleen and lung, which also express KLF13 (27). In addition, in T lymphocytes, the expression patterns of PRP4 and KLF13 (28) mirror each other with resting cells having very low or undetectable levels of these proteins until 3 days after activation, when both proteins are significantly induced. PRP4 belongs to a family of serine/arginine-rich protein-specific kinases that recognize serine-arginine-rich substrates (34). The catalytic domain of PRP4 shows significant similarity to the JNK/stress-activated protein kinase type of MAPK including the TPY motif, suggesting that PRP4 may play an important role in cell differentiation (35). PRP4 has also been reported to mediate cellular signaling (36). The N terminus of PRP4 interacts with proteins involved in splicing and nuclear hormone-regulated chromatin remodeling (37). Recently, Bennett et al. (38) reported that the C terminus of PRP4 interacts with HIV-2 Gag, although HIV-2 Gag polyprotein is not phosphorylated by PRP4. In our study, a yeast two-hybrid screen demonstrated that PRP4 interacts with KLF13. We confirmed this interaction by reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation experiments, because interactions detectable in multiple binding assays are unlikely to be experimental false positives (39). In addition, we also demonstrated that KLF13 is a substrate of PRP4 in kinase assays using PRP4 immunoprecipitated from transfected COS7 cells. However, PRP4 (499–1007), which retains its kinase domain, showed autophosphorylation, but completely lost its ability to phosphorylate KLF13 (data not shown), indicating that the truncated region of PRP4 is required for the interaction and/or phosphorylation of KLF13. These findings are consistent with the previous results of others, showing that PRP4 is capable of the phosphorylation of both transcription factors and serine/arginine-rich splicing factors (36).

KLF13 contains multiple potential phosphorylation sites. At least 18 putative serine phosphorylation sites and 3 threonine phosphorylation sites are predicted by NetPhos2.0 Server. Whether one or more of these sites is the PRP4 recognition sequence has not yet been determined. Although we have identified several serine phosphorylation sites between aa 264–88 in the C-terminal end of KLF13 (data not shown), deletion of this region does not completely abrogate the phosphorylation by PRP4, suggesting either that these sites are targets of other protein kinases or that multiple PRP4 phosphorylation sites work in concert.

KLF13 binds to the A/B region of the CCL5 promoter in a dose-dependent manner (27). Although phosphorylation of KLF13 by PRP4 results in a decreased affinity of KLF13 for the A/B site as demonstrated by EMSA, reporter gene assays using a CCL5 promoter luciferase reporter indicate that coexpression of KLF13 and PRP4 results in increased CCL5 promoter activity relative to transactivation by KLF13 alone. In contrast, coexpression of KLF13 and PRP4 (499–1007), which retains its kinase domain but is unable to phosphorylate KLF13, did not enhance transcription (data not shown). This indicates that the N-terminal region of PRP4 is not only important for the phosphorylation of KLF13, but also plays a role in regulating CCL5 expression. The apparent dichotomy between decreased KLF13 DNA binding induced by PRP4-mediated phosphorylation and increased CCL5 expression remains unclear, but may be related to the complexity of the CCL5 enhancesome (28). In this regard, Song et al. (40) reported that the transcriptional coactivators p300 CREB-binding protein (CBP) and p300-CBP-associated factor (PCAF) act cooperatively in stimulating KLF13 transcriptional activity. Nevertheless, p300/CBP and PCAF acetylate specific lysine residues in the zinc finger DNA-binding domain of KLF13 which disrupt KLF13 DNA binding. In comparison, we found that the mutation of two amino acids in the same zinc finger DNA-binding domain of KLF13 causes a dramatic increase in CCL5 reporter gene activity, although the mutated KLF13 bound to the CCL5 A/B site with much lower affinity (data not shown). Moreover, we recently confirmed that KLF13 recruits p300/CBP and PCAF to the CCL5 promoter in activated T lymphocytes (28). Studies are currently underway to determine whether PRP4 mediates changes in the acetylation states of KLF13 in concert with other acetyltransferase proteins, such as p300/CBP and PCAF and, therefore, reduces its DNA-binding affinity. We hypothesize that the phosphorylation of KLF13 by PRP4 may facilitate the assembly or disassembly of the multiprotein complex at the CCL5 promoter, enabling PRP4 to further modify transcriptional coactivators or repressors by phosphorylation, as many ERK/MAPK and cyclic-dependent kinases have been shown to associate with and phosphorylate transcription factors or transcriptional coactivators (41).

Control of CCL5 expression in T lymphocytes is complex. CCL5 transcription is controlled by an enhancesome composed of different factors at various times after T lymphocyte activation (28). KLF13, a sequence-specific DNA transcription factor, coordinates the induction of CCL5 expression in T lymphocytes by ordered recruitment of proteins to the CCL5 promoter, including Brahma-related gene 1 (Brg-1) (28). Brg-1 is an ATPase subunit of the SWI-SNF chromatin-remodeling complexes (42). It is recruited to chromatin by direct interactions with DNA-binding proteins (43). Interestingly, Dellaire et al. (37) demonstrated that Brg-1 interacts with the hypophosphorylated form of PRP4 in a transcription-dependent manner and appears to be a PRP4 substrate in vitro. Nuclear receptor corepressor, a component of the nuclear hormone corepressor complex, also interacts in vivo with human PRP4. In summary, PRP4 binds to and phosphorylates KLF13, enhancing CCL5 expression. Therefore, PRP4 is an important component of the enhancesome assembling over time at the CCL5 promoter in activated T lymphocytes.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant (to A.M.K.) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH R37 DK35008-23). A.M.K. is the Shelagh Galligan Professor of Pediatrics.

Abbreviations used in this paper: KLF13, Krüppel-like factor 13; HA, hemagglutinin; siRNA, small interfering RNA; RT-qPCR, real-time quantitative PCR; NLK, Nemo-like kinase; GUS, β-glucuronidase; Brg-1, Brahma-related gene 1; Ct, threshold cycle; CBP, CREB binding protein; PCAF, p300/CBP-associated factor.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zlotnik A, Yoshie O. Chemokines: a new classification system and their role in immunity. Immunity. 2000;12:121–127. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keane MP, Strieter RM. The role of CXC chemokines in the regulation of angiogenesis. Chem. Immunol. 1999;72:86–101. doi: 10.1159/000058728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell JJ, Butcher EC. Chemokines in tissue-specific and microenvironment-specific lymphocyte homing. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2000;12:336–341. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy PM, Baggiolini M, Charo IF, Hebert CA, Horuk R, Matsushima K, Miller LH, Oppenheim JJ, Power CA. International union of pharmacology: XXII. Nomenclature for chemokine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000;52:145–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi D, Zlotnik A. The biology of chemokines and their receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:217–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sallusto F, Mackay CR, Lanzavecchia A. The role of chemokine receptors in primary, effector, and memory immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:593–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schall TJ, Bacon K, Toy KJ, Goeddel DV. Selective attraction of monocytes and T lymphocytes of the memory phenotype by cytokine RANTES. Nature. 1990;347:669–671. doi: 10.1038/347669a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kameyoshi Y, Dorschner A, Mallet AI, Christophers E, Schroder JM. Cytokine RANTES released by thrombin-stimulated platelets is a potent attractant for human eosinophils. J. Exp. Med. 1992;176:587–592. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rot A, Krieger M, Brunner T, Bischoff SC, Schall TJ, Dahinden CA. RANTES and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α induce the migration and activation of normal human eosinophil granulocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1992;176:1489–1495. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahinden CA, Geiser T, Brunner T, von Tscharner V, Caput D, Ferrara P, Minty A, Baggiolini M. Monocyte chemotactic protein 3 is a most effective basophil- and eosinophil-activating chemokine. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:751–756. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taub DD, Sayers TJ, Carter CR, Ortaldo JR. α and β chemokines induce NK cell migration and enhance NK-mediated cytolysis. J. Immunol. 1995;155:3877–3888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuna P, Reddigari SR, Schall TJ, Rucinski D, Viksman MY, Kaplan AP. RANTES, a monocyte and T lymphocyte chemotactic cytokine releases histamine from human basophils. J. Immunol. 1992;149:636–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alam R, Stafford S, Forsythe P, Harrison R, Faubion D, Lett-Brown MA, Grant JA. RANTES is a chemotactic and activating factor for human eosinophils. J. Immunol. 1993;150:3442–3448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bacon KB, Premack BA, Gardner P, Schall TJ. Activation of dual T cell signaling pathways by the chemokine RANTES. Science. 1995;269:1727–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.7569902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder CC, Feng Y, Kennedy PE, Murphy PM, Berger EA. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton RE, Hill CM, et al. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath PD, Wu L, Mackay CR, LaRosa G, Newman W, et al. The β-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doranz BJ, Rucker J, Yi Y, Smyth RJ, Samson M, Peiper SC, Parmentier M, Collman RG, Doms RW. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the β-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway GP, Martin SR, Huang Y, Nagashima KA, Cayanan C, Maddon PJ, Koup RA, Moore JP, Paxton WA. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson PJ, Kim HT, Manning WC, Goralski TJ, Krensky AM. Genomic organization and transcriptional regulation of the RANTES chemokine gene. J. Immunol. 1993;151:2601–2612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson EL, Li X, Hsu FJ, Kwak LW, Levy R, Clayberger C, Krensky AM. Tumor-specific, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response after idiotype vaccination for B-cell, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood. 1996;88:580–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson PJ, Krensky AM. Chemokines, lymphocytes and viruses: what goes around, comes around. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1998;10:265–270. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Bleecker JL, De Paepe B, Vanwalleghem IE, Schroder JM. Differential expression of chemokines in inflammatory myopathies. Neurology. 2002;58:1779–1785. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ortiz BD, Krensky AM, Nelson PJ. Kinetics of transcription factors regulating the RANTES chemokine gene reveal a developmental switch in nuclear events during T-lymphocyte maturation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:202–210. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moriuchi H, Moriuchi M, Fauci AS. Nuclear factor-κB potently up-regulates the promoter activity of RANTES, a chemokine that blocks HIV infection. J. Immunol. 1997;158:3483–3491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schall TJ, Jongstra J, Dyer BJ, Jorgensen J, Clayberger C, Davis MM, Krensky AM. A human T cell-specific molecule is a member of a new gene family. J. Immunol. 1988;141:1018–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song A, Chen YF, Thamatrakoln K, Storm TA, Krensky AM. RFLAT-1: a new zinc finger transcription factor that activates RANTES gene expression in T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1999;10:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn YT, Huang B, McPherson L, Clayberger C, Krensky AM. Dynamic interplay of transcriptional machinery and chromatin regulates “late” expression of the chemokine RANTES in T lymphocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:253–266. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01071-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikolcheva T, Pyronnet S, Chou SY, Sonenberg N, Song A, Clayberger C, Krensky AM. A translational rheostat for RFLAT-1 regulates RANTES expression in T lymphocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:119–126. doi: 10.1172/JCI15336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang B, Wu P, Bowker-Kinley MM, Harris RA. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase expression by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α ligands, glucocorticoids, and insulin. Diabetes. 2002;51:276–283. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kojima T, Zama T, Wada K, Onogi H, Hagiwara M. Cloning of human PRP4 reveals interaction with Clk1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:32247–32256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103790200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song A, Patel A, Thamatrakoln K, Liu C, Feng D, Clayberger C, Krensky AM. Functional domains and DNA-binding sequences of RFLAT-1/KLF13, a Krüppel-like transcription factor of activated T lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:30055–30065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alahari SK, Schmidt H, Kaufer NF. The fission yeast prp4+ gene involved in pre-mRNA splicing codes for a predicted serine/threonine kinase and is essential for growth. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4079–4083. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.17.4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gross T, Lutzelberger M, Weigmann H, Klingenhoff A, Shenoy S, Kaufer NF. Functional analysis of the fission yeast prp4 protein kinase involved in pre-mRNA splicing and isolation of a putative mammalian homologue. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1028–1035. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyata Y, Nishida E. Distantly related cousins of MAP kinase: biochemical properties and possible physiological functions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;266:291–295. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang Y, Deng T, Winston BW. Characterization of hPRP4 kinase activation: potential role in signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;271:456–463. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dellaire G, Makarov EM, Cowger JJ, Longman D, Sutherland HG, Luhrmann R, Torchia J, Bickmore WA. Mammalian PRP4 kinase copurifies and interacts with components of both the U5 snRNP and the N-CoR deacetylase complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:5141–5156. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.14.5141-5156.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bennett EM, Lever AM, Allen JF. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Gag interacts specifically with PRP4, a serine-threonine kinase, and inhibits phosphorylation of splicing factor SF2. J. Virol. 2004;78:11303–11312. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11303-11312.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goehler H, Lalowski M, Stelzl U, Waelter S, Stroedicke M, Worm U, Droege A, Lindenberg KS, Knoblich M, Haenig C, et al. A protein interaction network links GIT1, an enhancer of Huntington aggregation, to Huntington's disease. Mol. Cell. 2004;15:853–865. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song CZ, Keller K, Chen Y, Stamatoyannopoulos G. Functional interplay between CBP and PCAF in acetylation and regulation of transcription factor KLF13 activity. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;329:207–215. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00429-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foulds CE, Nelson ML, Blaszczak AG, Graves BJ. Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling activates Ets-1 and Ets-2 by CBP/p300 recruitment. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:10954–10964. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10954-10964.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muchardt C, Reyes JC, Bourachot B, Leguoy E, Yaniv M. The hbrm and BRG-1 proteins, components of the human SNF/SWI complex, are phosphorylated and excluded from the condensed chromosomes during mitosis. EMBO J. 1996;15:3394–3402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barker N, Hurlstone A, Musisi H, Miles A, Bienz M, Clevers H. The chromatin remodelling factor Brg-1 interacts with β-catenin to promote target gene activation. EMBO J. 2001;20:4935–4943. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]