Abstract

Although children with Williams syndrome (WS) have relatively good structural language and concrete vocabulary abilities, they have difficulty with pragmatic aspects of language. To investigate the impact of pragmatic difficulties on listener-role referential communication, we administered a picture placement task designed to measure ability to verbalize message inadequacy to a speaker separated by a barrier. 57 children with WS aged 6 – 12 years participated. When messages were inadequate, children verbalized that a problem was encountered less than half the time. The likelihoods that children would indicate a message was insufficient and that children who verbalized message inadequacy also would effectively communicate the problem varied as a function of type of problem encountered, theory of mind knowledge, receptive vocabulary, and CA.

Keywords: Williams-Beuren syndrome, referential communication, conversational inadequacy, social communication, pragmatics, intellectual disability

Williams syndrome (WS) is a neurodevelopmental disorder resulting from a hemideletion of ~ 25 genes on chromosome 7q11.23 (Ewart et al., 1993; Morris, 2006), with a prevalence of 1 in 7500 live births (Strømme, Bjørnstad, & Ramstad, 2002); boys and girls are equally likely to be affected (American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Genetics, 2001). WS is characterized by mild to moderate intellectual disability or learning difficulties, dysmorphic facial features, and heart disease, especially supravalvar aortic stenosis (Morris, 2006). WS has drawn considerable attention from researchers due to its unusual cognitive and personality profiles. The WS cognitive profile is characterized by relative strengths in verbal short term memory and the structural and concrete vocabulary components of language accompanied by severe weakness in visuospatial construction (Mervis et al., 2000; Mervis & Morris, 2007; Udwin & Yule, 1991).

The WS personality profile involves high levels of sociability and empathy, over-eagerness to interact with others, and high levels of tension and sensitivity (Klein-Tasman & Mervis, 2003). Children with WS have been described as very sociable (Dilts et al., 1990), outgoing and talkative (Jones & Smith, 1975), approachable (Tomc et al., 1990), charming (Fryns et al., 1991), and unusually friendly (Preus, 1984). Despite these seemingly positive characteristics, individuals with WS demonstrate difficulty with peer relationships (e.g., Sullivan et al., 2003) with one study (Davies et al., 1998) reporting that 96% of parents and caregivers of adults with WS described problems with establishing friendships.

The combination of a relative strength in the structural and concrete vocabulary aspects of language and increased sociability with consistent problems in making friends and sustaining friendships suggests that children with WS likely have difficulty with the pragmatic aspects of language. The results of the few studies of pragmatics in WS are consistent with this position. In an early study, Udwin and Yule (1991) reported that individuals with WS were not well tuned toward their conversational partner. Laws and Bishop (2004) found that 15 of 19 children and young adults with WS met the criteria for pragmatic impairment on the Children’s Communication Checklist (CCC; Bishop, 1998), a parent questionnaire assessing language in a broad sense. Stojanovik (2006) compared the performance of five children with WS in a semi-structured conversation with a researcher to those of children with specific language impairment (SLI) matched for receptive vocabulary and grammatical ability and those of slightly younger typically developing (TD) children. Results indicated that regardless of whether the researcher asked for information or clarification, the responses of the WS group were less likely to be adequate than the responses of the SLI and TD groups. In particular, the WS group was more likely to provide too little information or to misinterpret what the researcher had meant and considerably less likely to produce a response that continued the conversation.

Why might children who have a syndrome associated with relative strengths in the structural and concrete vocabulary components of language demonstrate a significant weakness in pragmatic language abilities? Successful communication between two people involves taking into account what is known about the communicative partner, including his or her status, knowledge, and feelings and using this information to present the content to be communicated in a manner that will be effective for that communicative partner. Thus, successful communication depends at least in part on theory of mind (ToM), the ability to understand another’s perspective (Hale & Tager-Flusberg, 2005; Sperberg & Wilson, 1986; Tager-Flusberg, 1993). If individuals with WS have difficulty with ToM, this difficulty likely would contribute to their pragmatic problems.

Results of an early study of the ToM abilities of individuals with WS aged 9 – 23 years indicated that 94% passed the first-order ToM tasks administered and some also passed higher-level ToM tasks, leading the authors to conclude that ToM may be an “islet of preserved ability” in WS (Karmiloff-Smith et al., 1995, p. 202). This conclusion, however, was likely premature. First-order ToM as measured by false belief tasks is demonstrated by most TD children by age 3½ or 4 years (e.g. Wimmer & Perner, 1983; Tager-Flusberg, Baron-Cohen, & Cohen, 1993). In contrast, Tager-Flusberg, Sullivan, and Boshart (1997) found that only 43% of children with WS aged 5 – 9 years were able to pass false belief tasks. Furthermore, the performance of the children with WS was comparable to that of children with Prader-Willi syndrome and children with nonspecific mental retardation (MR) matched on CA, IQ, and standardized language measures. In a later study, Tager-Flusberg and Sullivan (2000) found that only about 25% of children with WS aged 4½ – 9 years passed false belief tasks, a rate significantly lower than that for carefully-matched children with Prader-Willi syndrome or MR of unknown etiology. Thus, the development of ToM by children with WS is considerably delayed.

In the present study, we consider an area of pragmatics that has not yet been examined for individuals with WS: referential communication. This is the type of communication that occurs in situations where the speaker’s goal is to convey information that will enable a listener to identify a referent from confusable alternatives, and the listener’s goal is to correctly identify the referent or to tell the speaker that the referent cannot be identified and explain why (Glucksberg, Krauss, & Higgins, 1975; Rosenberg & Cohen, 1967). Within this type of task, the listener is responsible for monitoring his or her comprehension of what the speaker has said, identifying any problems with the speaker’s message, and if necessary formulating a response indicating that a problem was encountered which includes information regarding the nature of the problem encountered. These skills are critical for successful social communication, as conversations typically build on information previously provided (Glucksberg et al., 1975). We addressed the listener’s role, focusing on verbal responses to three types of messages: messages that are ambiguous, messages that include a word the child does not understand, and messages with which the child cannot comply because the target object is not available. Because we were specifically interested in addressing within-group variability in referential communication ability and the factors related to this variability rather than in determining if difficulty in referential communication or the factors affecting referential communication were unique to WS, we included a large sample of children with WS but did not include a contrast group.

Referential Communication in Typical Development: The Listener’s Role

By age 8 or 9 years, TD children evidence near adult-level competence in the listener’s role in referential communication tasks (Glucksberg et al., 1975). Younger TD children, however, have considerable difficulty communicating adequately during these tasks. Ackerman (1981) and Robinson and Whittaker (1985) found that children aged 5 and 6 years did not consistently evaluate utterances for adequacy and therefore were not able to discriminate between ambiguous and informative utterances. Beal (1988; Beal & Belgrad, 1990) found that 5-and 6-year-olds were not able to tell the difference between what a speaker said literally and what the speaker meant to communicate. She suggested that children do not notice ambiguity within an utterance because they do not evaluate independently the literal meaning of the utterance and what they believe to be the speaker’s intended meaning. Consistent with Beal’s suggestion, if the possibility of ambiguity is pointed out explicitly, the performance of TD children this age improves considerably. For example, Ackerman (1979, 1981) showed that 5-and 6-year-old TD children were able to differentiate between ambiguous and informative utterances provided by the speaker if the children were warned that the speaker might try to trick them.

Referential Communication in Intellectual Disability Syndromes: The Listener’s Role

Several studies have addressed the performance of individuals with intellectual disability (ID) as listeners in referential communication tasks. Rueda and Chan (1980) examined referential communication skills in adolescents with moderate ID (mean CA = 15.75 years, mean MA = 3.67 years). In this project, both the speaker and the listener had ID. The speaker and listener were given identical sets of two pictures and the speaker was asked to describe the target picture so that the listener could determine which of the two pictures the speaker had described. Three types of cartoon picture pairs were used: (1) pairs that belonged to very different categories (e.g., clown and bell), (2) pairs that belonged to different subordinate level categories of the same basic level category (e.g., oak tree, fir tree; these pairs also differed in characteristics such as size or coloring), and (3) pairs that were identical except for three very minor characteristics (e.g., two clowns that were identical except for the shape of their hats, buttons, and shoes). Listener performance varied as a function of pair type: The correct picture was identified on 90% of Pair 1 trials, which was significantly more often than for Pair 2 (66%) or Pair 3 (51%) trials. Although the authors did not present data on the proportion of trials for which the listener asked for clarification from the speaker, the wording of the General Discussion suggested that requests for clarification were very rare, and the authors stressed the importance of research investigating listener skills.

Abbeduto, Short-Meyerson, Benson, and Dolish (1997) examined the roles of message type and speaker age on non-comprehension signaling by individuals with ID (CA: M = 15;7, range: 9;0 to 20;1) and TD children (CA: M = 6;1, range: 5;0 to 9;8) matched on nonverbal MA. In this study, the speaker, who was in a different room (and therefore invisible to the listener) gave the listener directions for how to move a small toy car along a simple road map. Two types of problematic directions were provided: (1) Incompatible directions in which the referent identified was not available and (2) Ambiguous directions in which the instructions provided were consistent with more than one of the available referents. In addition, the age of the speaker was manipulated to determine if participants differentially signaled non-comprehension as a function of whether the speaker was a child or an adult. Both the TD group and the ID group signaled noncomprehension more often for incompatible directions than for ambiguous directions. There was no effect of speaker age for either group. In the Incompatible condition, when children indicated that there was a problem, the TD group was more effective than the ID group in communicating the nature of the problem. Non-comprehension signaling was related to age equivalent score obtained on the Test for Reception of Grammar (TROG; Bishop, 1989), a measure of receptive grammatical ability.

Abbeduto et al. (2008) addressed non-comprehension signaling by adolescents with Fragile X syndrome (FXS), adolescents with Down syndrome (DS), and TD preschoolers, all matched for nonverbal MA. Three types of problematic directions were provided:

Incompatible directions in which the speaker referred to an item that was not present,

Novel directions in which the speaker used an unfamiliar word to refer to the target item, and

Ambiguous directions in which there were multiple exemplars of the target category the speaker named. The FXS and DS groups signaled non-comprehension significantly less often than TD preschoolers did. However, the pattern of likelihood of signaling non-comprehension was the same for all three groups: Signaling of non-comprehension was more likely when directions were incompatible than when they were ambiguous or included a novel label. Non-comprehension signaling was related to age equivalent score on the Test for Auditory Comprehension of Language – 3 (TACL-3; Carrow–Woolfolk, 1999) which measures comprehension of vocabulary, grammatical morphemes, and syntactic rules and relations. Although no relation was found between performance on the referential communication task and factors such as ToM, auditory memory, or maladaptive behavior, the authors note that the lack of significance may be due to small sample size. Furthermore, they suggest that these factors be examined again in future studies.

Present Study

In the present study, we used a modified version of Abbeduto et al.’s referential communication task (Abbeduto et al., 2008; Murphy & Abbeduto, 2003) to examine the ability of children with WS aged 6 – 12 years to verbally signal message inadequacy to a speaker. This ability, which is critical for successful collaboration in social discourse, requires the listener to monitor his or her comprehension of what the speaker has said, identify any problems, and then formulate a message that will elicit the information needed for clarification. Both the ability to indicate verbally that there was a problem with the speaker’s message and the ability to correctly identify the problem (assuming that a problem was indicated at all) were examined for three different types of problematic messages. Given the importance of the ability of the speaker and listener to keep in mind the perspective of their conversational partner for conversational success, we expected that successful performance on first-order false belief tasks (ToM) would be related to the child’s ability both to verbalize that a message was inadequate and to include an accurate statement of the problem encountered in his or her verbalization. In keeping with previous studies examining listener role referential communication, we also considered the effects of CA, general intellectual ability, nonverbal ability, and receptive language ability on children’s performance.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 57 children (23 boys, 34 girls) aged 6 – 12 years with genetically-confirmed classic-length WS deletions. None had been previously diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Of these children, 33 were consecutive participants within the 6 – 12 year age range in an ongoing study of cognitive and language development of individuals with WS at the University of Louisville. The remaining children were tested at a meeting of the Florida Regional Williams Syndrome Association or the biennial meeting of the National Williams Syndrome Association. The racial/ethnic constitution of the sample was 83% Caucasian, 12% Hispanic white, 3% Asian, and 2% African-American. Information regarding maternal education was available for 51 participants (89%). Of these mothers, 63% had a college degree, an additional 31% had graduated from high school, and 6% had not completed high school.

Standardized Assessments

Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (KBIT; Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990)

The KBIT is an individually administered assessment of verbal and nonverbal intelligence for individuals aged 4 – 90 years. The general population mean is 100, with a standard deviation of 15.

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III. (PPVT-III; Dunn & Dunn, 1997)

The PPVT-III is an individually administered measure of concrete receptive vocabulary for individuals aged 2½ –90 years. The mean for the general population is 100, with a standard deviation of 15.

Procedure

Developmental Assessment

The KBIT and PPVT-III were administered according to standard procedures, within a day of the referential communication task.

Referential Communication Task (modeled after Murphy & Abbeduto 2003 and Abbeduto et al., 2008)

This task was designed to press for the child’s ability to assess the adequacy of a message in a situation in which the child’s verbalization of message inadequacy can be evaluated. The child sat at a table opposite the experimenter (“speaker”) with a 48” × 22” opaque barrier between them to ensure that only verbal information was exchanged. The child was presented with a book containing 45 scenes, each missing one piece. Each scene was presented on a separate page. Next to each scene was a blank page containing a pocket which held either two or four smaller pictures varying in either one (e.g., type of animal – pig or horse) or two (e.g., shape and color) dimensions. A second experimenter (“assistant”) sat next to the child to help him/her turn the pages and to provide the necessary materials.

At the beginning of the task, the child was instructed that he/she was going to play a game with the experimenter (“speaker”) that involved putting small pictures on larger pictures (“scenes”) and that the experimenter would tell him/her which smaller picture was needed. The child also was informed that since there was a barrier between them, the experimenter could not see the child’s materials, and that therefore he/she should tell the experimenter if there was a problem doing what the experimenter had asked. The child was informed that the role of the adult (“assistant”) sitting next to the child was to get the materials out and then was reminded that any questions should be directed to the “speaker.” Before each trial, the assistant removed the smaller pictures from the pocket and placed them in a row directly under the presented scene. If the child directed a question to the assistant, the child was reminded to ask the speaker for help.

There were four instruction conditions. In the first condition (Control – 40% of trials), the information provided was adequate for the child to carry out the speaker’s request without assistance. This condition was included to confirm that children with WS were able to understand the task and follow the directions. The remaining conditions (Inadequate message conditions– 60% of trials) were designed to create three different types of situation in which the child would not be able to carry out the speaker’s request correctly without requesting further information (see sample items in Table 1). These conditions were:

Table 1.

Examples of inadequate speaker messages and codes for children’s verbalizations of message inadequacy

| Example | Condition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Impossible | Ambiguous | Unknown Word | |

| Speaker’s message | “Give the baby the bubbles.”

Available pictures: block and ball |

“Put the shape on the table.”

Available pictures: star and heart |

“Put the beryl candle on the cake.”

Available pictures: light blue candle and pink candle |

|

| |||

| Codes for child’s verbalization of problem | |||

|

| |||

| Effective | “I don’t have any bubbles.”

”I only have a block and a ball.” |

“Which shape?”

“They’re both shapes.” |

“I don’t know what ‘beryl’ means.”

“Is ‘beryl’ blue or is it pink?” |

| Too Vague | “Which one?”

“This bubble?” |

“This one?”

“The shape?” |

“This beryl?”

“Is this the beryl?” |

| Wrong Problem | “I have two bubbles.” | “There’s no shape.” | “I don’t have a beryl one.” |

Impossible (20% of trials): The speaker provided instructions using words familiar to the child; however, the item that the child was asked to place in the scene was unavailable.

Ambiguous (20% of trials): The speaker’s request used words familiar to the child; however, the instruction was vague enough that all pictures available to the child fulfilled the request.

Unknown Word (20% of trials): The speaker labeled the item that the child was asked to place in the scene with a word that, while correct, was not in the child’s vocabulary. Determination that the children were unlikely to understand the word was based on pilot data, and parents were asked to confirm that their child did not know the relevant words. To prevent the child from simply fast mapping the unknown word to the target object or characteristic (e.g., color), items and characteristics were ones for which the child knew a more common name.

Children were administered one of two quasi-random orders. The orders were constructed randomly except for two restrictions: (1) The first trial was always from the Control condition, and (2) no more than 3 items from the “control” or “problem” conditions were presented in succession. Due to the quasi-random presentation of items and use of the control condition to evaluate if children understood the task, no practice trials were included. As the results of previous studies (e.g., Abbeduto et al., 2008; Murphy & Abbeduto, 2003) have indicated that the inadequate message conditions were likely to vary in their level of difficulty, the analyses conducted allowed for the examination of both overall level of performance and performance as a function of inadequate message condition.

Unexpected Contents Theory of Mind (ToM) Task (Tager-Flusberg & Sullivan, 2000)

Each child completed two unexpected contents tasks measuring first-order ToM (modeled after Tager-Flusberg & Sullivan, 2000) to indicate if he or she demonstrated representational understanding of beliefs. In each task, the child was shown a closed familiar container which contained unexpected contents (an empty peanut butter jar containing a miniature toy basketball and an empty crayon box containing paper clips). The child was first asked a prediction question (“What do you think is in here?”). After answering the prediction question, the container was opened and the child was shown what was inside and then the container was resealed. The child was then asked a reality control question (“What is really in here?”). This question was used to confirm that the child knew what was actually inside the container. Next the child was asked an ignorance question (“If we show this to your mom, will she know what is in here?”), and a false belief question (“What will your mom say is in here?”). The ignorance and false belief questions were used to determine if the participant was able to distinguish between his/her true belief and another person’s false belief. To pass ToM, the children had to answer all four questions on both tasks correctly.

Coding

The referential communication tasks were videotaped for coding purposes. The camera was set up to film the book only, in order to determine which picture the child placed on the larger scene. The videotape was transcribed to document the communication between the child and the examiners. Responses to each of the Impossible, Ambiguous, and Unknown Word trials were first coded dichotomously (“yes” or “no”) to indicate if the child verbally told the speaker that a problem had been encountered. Responses that were coded “yes” were further coded into three categories based on their effectiveness in conveying the problem encountered or the additional information needed. Examples of each category are provided in Table 1.

Effective: The child provided specific information regarding the nature of the problem encountered.

Too Vague: The information the child provided was too vague for the speaker to determine the specific problem. Responses in this category included utterances in which the child did not take into account that, because of the barrier between them, the examiner could not see what the child saw; child requests that the examiner repeat her message or confirm that the child had heard the message correctly; and utterances that made it clear that the child had encountered a problem but did not provide enough information for the examiner to determine the specific problem.

Wrong Problem: The child identified the wrong problem.

The primary coder coded all of the videotapes. To assess reliability, a second person independently coded 12 randomly selected tapes. Percentage of agreement (99%) and Cohen’s kappa (κ = .99) indicated very high reliability.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics for CA, KBIT composite IQ, KBIT Nonverbal standard score, and PPVT-III standard score are reported in Table 2. ToM ability was coded dichotomously (pass vs. fail); 16 children passed and 40 children failed. One child did not complete the ToM assessment. Due to administration errors or problems with videotape quality, 18 of 2520 trials could not be scored. Accordingly, performance on the referential communication task was measured by proportion of items correct rather than number of items correct. No significant effect of order was found; therefore, in the analyses reported below, order was not included as a factor.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for CA, cognitive, and language variables

| CA (in years) | KBIT IQ Composite | KBIT Nonverbal Standard Score | PPVT-III Standard Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 9.24 | 72.93 | 76.44 | 81.96 |

| SD | 1.92 | 15.17 | 14.54 | 14.46 |

| Range | 6.00 – 12.74 | 40 – 97 | 47 – 110 | 50 – 115 |

Overall Referential Communication Performance

Children performed very well on the control items (mean proportion correct = .94, SD = .07, range: .77 – 1.00), indicating that when the speaker’s message was adequate, children with WS were able to complete the task successfully. Although children performed significantly (αfw = .02, ps < .001) better on the items in which two referents were provided than on the four referent items, mean proportion correct for both types of items was 90% or higher (2-referents: mean proportion correct = .99, SD = .05; 4-referents, 1 dimension: mean proportion correct = .91, SD = .02; 4-referents, 2 dimensions: mean proportion correct = .90, SD = .02). In contrast, on the inadequate message items, children indicated verbally that there was a problem less that 50% of the time (mean proportion = .45, SD = .30, range: 0 – .93). No significant difference was found in the likelihood of verbalizing message inadequacy as a function of referent dimension (2-referents vs. 4-referents, 1 dimension vs. 4-referents, 2 dimensions); therefore, all remaining analyses were collapsed across this factor.

To explore the relations among CA, nonverbal cognitive ability, receptive vocabulary ability, ToM ability, and the proportion of trials on which the child’s verbalization indicated that the speaker’s message was inadequate, Pearson correlations were computed (Table 3). The variables most closely related to the verbalization measure were CA and ToM ability.

Table 3.

Pearson correlations among verbalizing message inadequacy in referential communication conditions, CA, and cognitive variables

| CA | KBIT Nonverbal SS | PPVT-III SS | ToM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref Comm % message inadequacy verbalizeda | .48*** | .11 | .26 | .50*** |

| Impossible | .24 | .28* | .29* | .32* |

| Unknown | .52*** | -.004 | .20 | .46*** |

| Ambiguous | .48*** | .05 | .22 | .53*** |

| CA | -.18 | -.05 | .39** | |

| KBIT Nonverbal SS | .53*** | .23 | ||

| PPVT-III SS | .41** |

Percent of inadequate message trials on which child verbally indicated that there was a problem complying with the speaker’s request

p < .01,

p < .001

Performance as a Function of Inadequate Message Condition

A one-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to determine if the likelihood of verbalization of message inadequacy varied as a function of inadequate message condition. A significant effect of condition was found [F(2,112) = 43.61, p < .001, np2 = .44]. Pairwise comparisons (αfw= .02, all ps < .001) indicated that performance was best in the Impossible condition (M = 0.64, SD = .32), next best in the Unknown Word Condition (M = 0.44, SD = .36), and worst in the Ambiguous condition (M = 0.29, SD = .32).

Pearson correlations between likelihood of verbal identification of message inadequacy as a function of condition and CA, KBIT Nonverbal standard score, PPVT-III standard score, and ToM are presented in Table 3. ToM ability was related to the likelihood of verbalizing message inadequacy in all three inadequate message conditions. CA was significantly related to performance in the Ambiguous and Unknown Word conditions but not the Impossible condition. KBIT IQ, KBIT Nonverbal standard score, and PPVT-III standard score were significantly related to performance only in the Impossible condition.

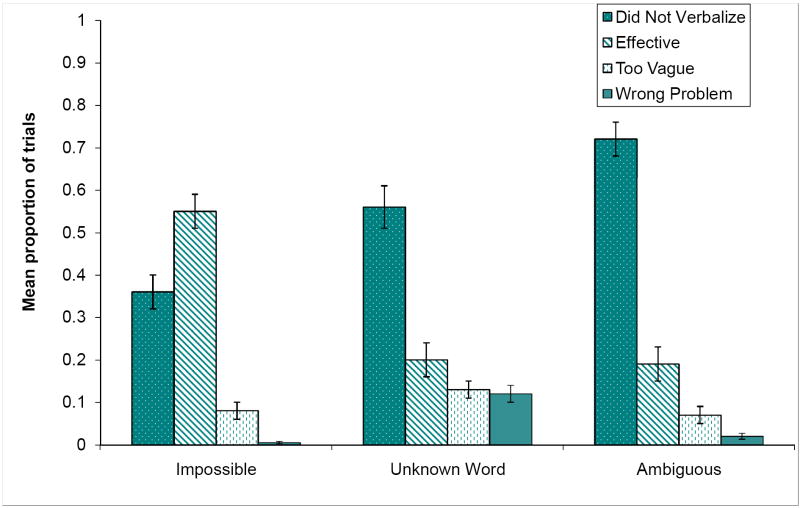

To determine if there were differences as a function of inadequate message condition in the proportion of messages children produced at a particular level of effectiveness, separate repeated measures ANOVAs were computed for each of the three levels of message effectiveness. Proportions of each type of message effectiveness as a function of condition are presented in Figure 1; the proportion of trials on which the child did not verbally indicate there was a problem is also shown. The likelihood that a child would effectively communicate the specific problem varied as a function of condition [F(1.66, 92.77) = 57.42, p < .001, np2 = .51]. Pairwise comparisons indicated that children were significantly more likely to effectively communicate the specific problem encountered in the Impossible condition than in the Unknown Word and Ambiguous conditions (αfw= .02, all ps < .02).

Figure 1.

Classification of level of communicative effectiveness of message inadequacy as a function of condition. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Significant differences among conditions also were found in the likelihood the child would provide a verbalization that was too vague to convey the information needed to specify the problem encountered [F(1.70,95.06) = 4.44, p = .02, np2 = .07]. Pairwise comparisons (αfw= .02) indicated that children were significantly more likely to provide indications of message inadequacy that were too vague in the Unknown Word condition (p = .004) than in the Ambiguous or Impossible conditions. The majority of the verbalizations that were classified “too vague” (54%) involved a ToM error in which the child did not take into account the fact that due to the opaque barrier between them, the examiner was unable to see what the child could see.

Finally, significant differences among conditions were found in the likelihood that the child would indicate that there was a problem, but the problem indicated was wrong [F(1.18,65.81) = 18.33, p < .001, np2 = .25]. Pairwise comparisons (αfw= .02) indicated that children were most likely to indicate the wrong problem in the Unknown Word condition, next most likely in the Ambiguous condition, and least likely in the Impossible condition (all ps < .02). Pearson correlations examining the relations between the proportion of trials for which effective communication of the problem was provided (both overall and as a function of condition) and CA, KBIT Nonverbal standard score, PPVT-III standard score, and ToM ability are presented in Table 4. Only ToM ability and CA were related to overall likelihood of communicating specific information regarding the nature of the problem encountered. Examination of the likelihood of effective communication as a function of condition indicated significant correlations with ToM and PPVT standard score for all three conditions, significant correlations with CA for the Unknown and Ambiguous conditions, and a significant correlation with KBIT Nonverbal standard score only for the Impossible condition.

Table 4.

Pearson correlations among effective communication of the nature of the problem with the speaker’s message, CA, and cognitive variables

| CA | KBIT Nonverbal SS | PPVT-III SS | ToM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % “Effective”a | .30* | .12 | .27 | .43** |

| Overall | ||||

| % “Effective”a | .23 | .31* | .27* | .32* |

| Impossible | ||||

| % “Effective”a | .53*** | .07 | .35** | .65*** |

| Unknown | ||||

| % “Effective”a | .53*** | .06 | .32* | .59*** |

| Ambiguous | ||||

| CA | -.30* | -.13 | .39** | |

| KBIT Nonverbal SS | .49*** | .21 | ||

| PPVT-III SS | .40** |

Percent of inadequate message trials on which the child explicitly stated the problem with the speaker’s message

p ≤ .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Prediction of Overall Verbalization of Message Inadequacy

To determine if CA, KBIT Nonverbal standard score, PPVT-III standard score, and ToM predicted the overall likelihood that children would indicate verbally that a speaker’s message was inadequate, a regression model was computed. For this analysis, a single proportion was computed for each child including all conditions (see Table 5 for regression analysis). This combination of variables significantly predicted 32% of the variance in overall verbalization of message inadequacy (p < .001), with only CA and ToM significantly contributing to the prediction. The likelihood of verbalizing that a message was inadequate was positively related to CA, increasing verbalization by 6% for every year in CA. Children who demonstrated first-order ToM tended to verbalize message inadequacy more frequently than did children who did not demonstrate first-order ToM, by 17.7%.

Table 5.

Regression analysis summary for predictors of children’s verbal indication of a problem and predictors of children’s effective communication of the specific problem with the speaker’s message

| Measure and Analysis | R2 | Adjusted R2 | F (df) | Factors (B; SE B; β) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbalized problem: Overall | .37 | .32 | 7.31(50) *** | CA (.059; .020; .389) **

NVIQ (.001; .003; .045) PPVT (.003; .003; .147) ToM (.177; .088; .278) * |

|

| ||||

| Verbalized problem: Impossible Condition | .20 | .14 | 3.12(50) * | CA (.040; .024; .245)

NVIQ (.005; .003; .228) PPVT (.003; .003; .134) ToM (.081; .107; .117) |

|

| ||||

| Verbalized problem: Unknown Word Condition | .37 | .31 | 7.18(50) *** | CA (.079; .024; .419) **

NVIQ (-.001; .003; -.056) PPVT (.004; .004; .144) ToM (.202; .110; .255) |

|

| ||||

| Verbalized problem: Ambiguous Condition | .37 | .32 | 7.48(50) *** | CA (.057; .022; .339) *

NVIQ (-.001; .003; -.024) PPVT (.002; .003; .108) ToM (.255; .098; .359) * |

| Effectively Verbalized: Impossible Condition | .20 | .14 | 3.15(50) * | CA (.043; .024; .262)

NVIQ (.006; .003; .263) PPVT (.002; .003; .089) ToM (.080; .108; .115) |

|

| ||||

| Effectively Verbalized: Ambiguous Condition | .49 | .45 | 12.02(50) *** | CA (.057; .017; .390) **

NVIQ (-.002; .002; -.080) PPVT (.004; .002; .231) ToM (.222; .076; .326) ** |

|

| ||||

| Effectively Verbalized: Unknown Word Condition | .55 | .51 | 15.27(50) *** | CA (.053; .016; .369) **

NVIQ (.002; .002; -.090) PPVT (.005; .002; .240) * ToM (.256; .070; .425) ** |

p ≤ .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Separate regression analyses for the Impossible, Unknown Word, and Ambiguous conditions were also computed. For the Impossible condition, the model significantly predicted 20% of the variance (p = .02). However, none of the predictors contributed significantly to the model. In the Unknown Word condition, the model significantly predicted 31% of the variance in the likelihood that a child would verbalize that a message was inadequate (p < .001) with only CA contributing significantly to the prediction. With all other variables held constant, the likelihood of verbalizing that a message was inadequate was positively related to CA, increasing verbalization by 8% for every year in CA. Finally, for the Ambiguous condition, the same model significantly predicted 32% (p < .001) of the variance in the verbal indication of message inadequacy, with both CA and ToM producing significant effects. The likelihood of verbal indication that a message was inadequate was significantly positively related to CA, increasing verbalization by 6 % for every year in age, and children who demonstrated first-order ToM tended to verbalize that a message was inadequate more frequently than children who did not demonstrate first-order ToM, by 26%.

Factors Affecting Effective Communication

To determine if CA, KBIT Nonverbal standard score, PPVT-III standard score, and ToM predicted the likelihood that children would effectively communicate the problem with the speaker’s message in each of the three inadequate message conditions, a separate regression model was computed for each condition. All three models were significant (see Table 5). However, the predictors accounted for considerably more variance in the Ambiguous (49%) and Unknown Word (51.4%) conditions than in the Impossible condition (13.7%). No factors contributed significantly to effectively verbalizing message inadequacy in the Impossible condition. CA significantly contributed to the models in both the Ambiguous and Unknown Word conditions, with the likelihood of effectively verbalizing message inadequacy increasing 5% in the Unknown Word condition and 6% in the Ambiguous condition for every year in age. Furthermore, children who demonstrated first-order ToM were significantly more likely to effectively verbalize message inadequacy in both the Unknown Word condition (26%) and the Ambiguous condition (22%). PPVT-III standard score significantly contributed to the model in the Unknown Word condition, with the likelihood of effective verbalization of message inadequacy increasing 0.5% for every standard score.

DISCUSSION

Difficulties verbalizing message inadequacy during conversations are likely to create problems in social interactions (Abbeduto & Short-Meyerson, 2002; Murphy & Abbeduto, 2003; Abbeduto et al., 2006, Abbeduto et al., 2008). The listener is responsible for monitoring his or her comprehension of what the speaker has said, identifying any problems with the speaker’s message, and if necessary formulating a response indicating that a problem was encountered and the specific nature of the problem. These skills are critical for successful social communication, as conversations typically build on information previously provided (Glucksberg et al., 1975). The aim of the present study was to evaluate this ability by examining the referential communication skills used by children with WS when taking the role of listener in a referential communication task. We considered both the ability to verbally indicate that a message was inadequate and the ability to identify the specific problem with the message.

Likelihood and Effectiveness of Verbalizing Message Inadequacy

Even the youngest children in this study (age 6 years) reliably carried out the speaker’s request when the necessary materials were available and the vocabulary used by the speaker was understood. However, across the age range included (6 – 12 years), children with WS, when confronted with requests that they could not fulfill correctly, did not reliably indicate verbally that there was a problem with the speaker’s message. Instead, more than half the time children responded by placing one or more of the smaller pictures in the scene rather than asking a question or stating that they could not comply. The present study did not include a control group. However, a general idea of how the performance of the children with WS would compare to that of younger TD children may be obtained by considering the data from the TD control group (CA 3 – 6 years) in Abbeduto et al. (2008), after which the present study was modeled. This comparison indicates clearly that the referential communication skills of 6 – 12-year-old children with WS are considerably more limited than those of 3 – 6-year-old TD children. The WS group performed somewhat worse than the TD group in the Impossible condition, verbalizing that there was a problem 64% of the time compared to 77% for the TD group. In the other two conditions, the WS group was considerably less likely than the TD comparison group in Abbeduto et al. to indicate verbally that there was a problem (Unknown Word: 44% vs. 67%; Ambiguous: 29% vs. 72%).

The effectiveness of the child’s verbalization of the problem encountered varied systematically as a function of the type of problem. In the condition in which the problem was most obvious (Impossible), children effectively indicated the specific problem (that they did not have the necessary picture) 55% of the time. In the conditions for which the problem was less obvious, the children were much less likely to communicate the problem effectively (19% Ambiguous, 20% Unknown Word). Verbalizations that were too vague to indicate the specific problem were most common in the Unknown Word condition, and more than half of these verbalizations indicated a problem with ToM (not taking into account that, due to the opaque barrier, the experimenter could not see the child’s materials or gestures/actions). Verbalizations that identified the wrong problem were most common in the Unknown Word condition, next most common in the Ambiguous condition, and hardly ever occurred in the Impossible condition.

These findings are consistent with prior research examining the listener-role referential communication skills of both TD children and individuals who have other syndromes associated with ID. Abbeduto and his colleagues (Abbeduto et al., 2008; Murphy & Abbeduto, 2003) found that adolescents and young adults with DS or FXS also were not likely to verbalize message inadequacy, performing at a level significantly lower than that of TD preschoolers matched for nonverbal MA. As in the present study, the groups studied by Abbeduto and colleagues were most likely to verbally indicate that there was a problem with the speaker’s message when the necessary materials were not available. Unlike in the present study, Abbeduto and colleagues did not find a significant difference in the likelihood of participants verbally indicating a problem with the speaker’s message as a function of whether the message was ambiguous or was incomprehensible because it contained an unknown word. This difference may be due to lower power as a result of the smaller number of participants in each group in their study.

Although this is the first study of the referential communication abilities of individuals with WS, the findings are consistent with those that have been reported regarding difficulties in carrying on conversations or responding appropriately to what their communicative partners have said. The tendency of children with WS to respond to a conversational partner’s utterance as though it were understood even when it was not is a problem commonly reported by parents of children with WS. For example, Peregrine, Rowe, and Mervis (2005) found that on the Children’s Communication Checklist-2 (CCC-2; Bishop, 2003), parents frequently reported that their child with WS took in only a few words in a sentence, leading to misunderstandings. Laws and Bishop (2004) reported that parents of adolescents and young adults with WS were significantly less likely to have coherent conversations than were much younger TD children. Stojanovik and her colleagues (Stojanovik et al., 2001; Stojanovik 2006) reported high levels of conversational inadequacy in children with WS (see also Udwin & Yule, 1991), documenting both a tendency to provide too little information and considerable difficulty interpreting either the literal or the inferential meaning of the speaker’s message. Results of the present study extend these findings by demonstrating that the amount of difficulty individuals with WS have in conveying both the existence of a conversational inadequacy and the specific nature of the problem is affected by the type of problem encountered.

Predictors of Likelihood and Effectiveness of Verbalizing Message Inadequacy

In the present study, we considered several variables as potential predictors both of the likelihood of verbalizing message inadequacy and the likelihood of effectively communicating the specific problem. Variables examined included CA, nonverbal intellectual ability, receptive vocabulary ability, and ToM. Both CA and ToM contributed significantly and independently to the prediction of overall likelihood that message inadequacy would be verbalized. These factors also both contributed significantly and independently to the likelihood that message inadequacy would be verbalized in the Ambiguous condition. Only CA significantly and independently contributed to the likelihood that message inadequacy would be verbalized in the Unknown Word condition and none of the predictors independently were significantly related to the likelihood that message inadequacy would be verbalized in the Impossible condition. Examining predictors of the likelihood that children would effectively communicate the problem encountered, we found that CA and ToM significantly and independently contributed to the likelihood of effectively verbalizing the problem in the more difficult conditions (Ambiguous and Unknown Word) but none of the predictors significantly contributed independently to performance in the easiest condition (Impossible). PPVT-III standard score also contributed significantly to effective communication in the Unknown Word condition.

The present findings relating CA to referential communication ability are consistent with those reported in previous studies. Several research groups have reported an effect of CA on listener-role performance of TD children, with TD preschoolers performing significantly worse than TD school-age children and reliable and effective performance consistently present beginning at about 8 years of age (Ackerman, 1981; Beal, 1988; Beal & Belgrad, 1990; Robinson & Whittaker, 1985). These studies did not examine the role of ToM in listener-role performance. Abbeduto et al. (2008), in a study including adolescents who had FXS or DS and considerably younger TD controls found no effect of ToM on listener role referential communication performance. The discrepancy between their findings and the findings of the present study, in which ToM was strongly related to listener-role referential communication skill, may be due to differences in the methods used to assess ToM. Abbeduto et al. (2008) used a ToM task which assessed both first- and second-order ToM and used proportion of ToM questions answered correctly as the measure of ToM ability. In contrast, the ToM measure used in the present study assessed only first-order ToM and, following Tager-Flusberg and her colleagues (Sullivan & Tager-Flusberg, 1999: Sullivan, Winner, & Tager-Flusberg, 2003) we classified children categorically (pass, fail) based upon whether they correctly answered all of the ToM questions. Consistent with the present results, Murphy and Abbeduto (2003), in a preliminary analysis of the data from the participants in the Abbeduto et al. (2008) study, reported an effect of ToM for adolescents with FXS on a listener-role referential communication task. Finally, Abbeduto et al. (2008) found that receptive language age equivalent on the TACL was a significant predictor of referential communication performance. Though we did not find receptive vocabulary to be a significant predictor of overall referential communication performance, it was a significant predictor of the likelihood that children would effectively communicate to a speaker that they did not understand a word used to label an item.

Limitations

We must acknowledge some limitations of this study. First, because we did not include a contrast group, we were not able to address the question of whether the difficulties children with WS have with referential communication are similar to or different from those demonstrated by other groups with ID. Second, we did not include a specific measure of expressive language ability. Further research is warranted to examine the relation between expressive language and the ability to verbalize message inadequacy. Future studies also should consider if individuals with WS would be more likely to verbalize message inadequacy in situations in which instructional inadequacies are made more salient (e.g., being explicitly told that the speaker may try to trick them) in addition to examining referential communication in situations which more closely resemble natural conversational speaking contexts. Finally, because the purpose of the present study was to examine verbalizations of message inadequacy, the videotaping method used documented what the child said and which picture(s) the child selected but did not show the child’s face. Therefore, nonverbal indications of message inadequacy (e.g., puzzled facial expressions) were not captured. Further research is needed to determine the extent to which children with WS provide nonverbal cues of breakdowns in communication.

Conclusions

Despite increased sociability and relative strengths in concrete vocabulary and the structural aspects of language, children with WS do not reliably indicate to their conversational partner when a message is inadequate. Even when they do indicate message inadequacy, children with WS often do not indicate the specific problem and in some cases even identify the wrong problem. These findings provide further evidence of a pragmatic impairment in WS. These pragmatic problems are related to difficulty understanding false belief. It is likely that the difficulty that children with WS have in referential communication and more specifically, verbalizing message inadequacy contributes to the frustrations they and their communicative partners frequently encounter during social interactions. Understanding referential communication impairments is a crucial step toward the development of interventions to address the social communication weaknesses of children with WS.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants R37 HD29957 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and R01 NS35102 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. We thank the children and their parents for their enthusiastic participation in our research. Ella Peregrine, Sondra Hutchins, and Ivory Rollins assisted with data collection. Sarah Douglas assisted in data coding and Doris Kistler provided consultation on statistical analyses.

References

- Abbeduto L, Murphy MM, Kover ST, Giles ND, Karadottir S, Amman A, et al. Signaling noncomprehension of language: A comparison of Fragile X syndrome and Down syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2008;113:214–230. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2008)113[214:SNOLAC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbeduto L, Murphy MM, Richmond EK, Amman A, Beth P, Weissman MD, Kim, et al. Collaboration in referential communication: Comparison of youth with Down syndrome or Fragile X syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2006;111:170–183. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[170:CIRCCO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbeduto L, Short-Meyerson K. Linguistic influences on social interaction. In: Goldstein H, Kaczmarek LA, editors. Promoting social communication: Children with developmental disabilities from birth to adolescence Communication and language intervention series. Vol. 10. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Co; 2002. pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Abbeduto L, Short-Meyerson K, Benson G, Dolish J. Signaling of noncomprehension by children and adolescents with mental retardation. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1997;40:20–32. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4001.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman B. Children’s understanding of definite descriptions: Pragmatic inferences to the speaker’s intent. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1979;28:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(79)90098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman B. Encoding specificity in the recall of pictures and words in children and adults. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1981;31:193–211. doi: 10.1016/0022-0965(81)90012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Genetics. Health care supervision for children with Williams syndrome. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1192–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal C. Children’s knowledge about representations of intended meaning. In: Astington JW, Harris PL, editors. Developing theories of mind. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1988. pp. 315–325. [Google Scholar]

- Beal CR, Belgrad SL. The development of message evaluation skills in young children. Child Development. 1990;61:705–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DVM. Test for Reception of Grammar. Manchester, England: University of Manchester; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DVM. Development of the Children’s Communication Checklist (CCC): A method for assessing qualitative aspects of communicative impairment in children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39:879–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DVM. The children’s communication checklist. 2. London: Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Carrow-Woolfolk E. Test for Auditory Comprehension of Language-3. Allen, TX: DLM Teaching Resources; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Davies M, Udwin O, Howlin P. Adults with Williams syndrome: Preliminary study of social, emotional, and behavioral difficulties. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;172:273–276. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilts C, Morris CA, Leonard COL. A hypothesis for the development of a behavioral phenotype in Williams syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Supplement. 1990;6:126–131. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320370622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LE, Dunn LE. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—III. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ewart A, Morris C, Atkinson D, Jin W, Sternes K, Spallone P, Stock A, Leppert M, Keating M. Hemizygosity at the elastin locus in a developmental disorder, Williams syndrome. Nature Genetics. 1993;5:11–16. doi: 10.1038/ng0993-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryns J, Borghgraef M, Volcke P, van den Berge H. Adults with Williams syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1991;40:253. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320400228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glucksberg S, Krauss RM, Higgins ET. The development of referential communication skills. In: Horowitz FE, editor. Review of child development research. Vol. 4. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1975. pp. 305–345. [Google Scholar]

- Hale CM, Tager-Flusberg H. Social communication in children with autism. Autism. 2005;9:157–178. doi: 10.1177/1362361305051395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K, Smith D. The Williams elfin facies syndrome. Journal of Pediatrics. 1975;86:718–723. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(75)80356-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmiloff-Smith A, Klima E, Bellugi U, Grant J, Baron-Cohen S. Is there a social module? Language, face processing, and theory of mind in individuals with Williams syndrome. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1995;7:196–208. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1995.7.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Tasman BP, Mervis CB. Distinctive personality characteristics of 8-, 9-, and 10-year-old children with Williams syndrome. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2003;23:271–292. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2003.9651895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws G, Bishop DVM. Pragmatic language impairment and social deficits in Williams syndrome: a comparison with Down’s syndrome and specific language impairment. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2004;39:45–64. doi: 10.1080/13682820310001615797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mervis CB, Morris CA. Williams syndrome. In: Mazzocco MMM, Ross J, editors. Neurogenetic developmental disorders: Variation of manifestation in childhood. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mervis CB, Morris CA, Bertrand J, Robinson BF. Williams syndrome: Findings from an integrated program of research. In: Tager-Flusberg H, editor. Neurodevelopmental disorders. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1999. pp. 65–110. [Google Scholar]

- Mervis CB, Robinson BF, Bertrand J, Morris CA, Klein-Tasman BP, Armstrong SC. The Williams Syndrome Cognitive Profile. Brain & Cognition. 2000;44:604–628. doi: 10.1006/brcg.2000.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CA. The dysmorphology, genetics, and natural history of Williams-Beuren syndrome. In: Morris CA, Lenhoff HM, Wang PP, editors. Williams-Beuren syndrome: Research, evaluation, and treatment. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2006. pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M, Abbeduto L. Language and communication in Fragile X syndrome. International Review of Research in Mental Retardation. 2003;27:83–119. [Google Scholar]

- Peregrine E, Rowe ML, Mervis CB. Pragmatic language difficulties in children with Williams syndrome. Society for Research in Child Development; Atlanta, GA: 2005. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Preus M. The Williams syndrome: Objective definition and diagnosis. Clinical Genetics. 1984;25:422–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1984.tb02011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson EJ, Whittaker SJ. Children’s responses to ambiguous message and their understanding of ambiguity. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:446–454. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S, Cohen BD. Speakers’ and listeners’ processes in a word-communication task. Science. 1964;145:1201–1203. doi: 10.1126/science.145.3637.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda R, Chan K. Referential communication skill levels of moderately mentally retarded adolescents. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1980;85:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber D, Wilson D. Relevance: Communication and cognition. Oxford: Blackwell; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanovik V, Perkins M, Howard S. Language and conversational abilities in Williams syndrome: How good is good? International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2001;36(supplement):234–240. doi: 10.3109/13682820109177890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojanovik V, Perkins M, Howard S. Social interaction deficits and conversational inadequacy in Williams syndrome. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2006;19:157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Strømme P, Bjørnstadt PG, Ramstad K. Prevalence estimation of Williams syndrome. Journal of Child Neurology. 2002;17:269–271. doi: 10.1177/088307380201700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan K, Tager-Flusberg H. Second-order belief attribution in Williams syndrome: Intact or impaired? American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1999;104:523–532. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(1999)104<0523:SBAIWS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan K, Winner E, Tager-Flusberg T. Can adolescents with Williams syndrome tell the difference between lies and jokes? Developmental Neuropsychology. 2003;23:85–103. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2003.9651888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg H. What language reveals about the understanding of minds in children with autism. In: Baron-Cohen S, Tager-Flusberg H, Cohen D, editors. Understanding other minds: Perspectives from autism. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 138–177. [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg H, Baron-Cohen S, Cohen D. An introduction to the debate. In: Baron-Cohen S, Tager-Flusberg H, Cohen D, editors. Understanding other minds: Perspectives from autism. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg H, Sullivan K. A componential view of theory of mind: Evidence from Williams syndrome. Cognition. 2000;76:59–89. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg H, Sullivan K, Boshart J. Executive functions and performance on false belief tasks. Developmental Neuropsychology. 1997;13:487–493. [Google Scholar]

- Tomc SA, Williamson NK, Pauli RM. Temperament in Williams syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1990;36:345–352. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320360321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udwin O, Yule W. A cognitive and behavioural phenotype in Williams syndrome. Journal of Clinical & Experimental Neuropsychology. 1991;13:232–244. doi: 10.1080/01688639108401040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer H, Perner J. Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition. 1983;13:103–128. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(83)90004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]