Abstract

The authors tested a mediation model in which childhood hostility and sociability were expected to influence the development of intentions to use alcohol in the future through the mediating mechanisms of developing attitudes and norms. Children in 1st through 5th grades (N = 1,049) from a Western Oregon community participated in a longitudinal study involving four annual assessments. Hostility and sociability were assessed by teachers= ratings at the first assessment, and attitudes, subjective norms and intentions were assessed by self-report at all four assessments. For both genders, latent growth modeling demonstrated that sociability predicted an increase in intentions to use alcohol over time, whereas hostility predicted initial levels of these intentions. These personality effects were mediated by the development of attitudes and subjective norms, supporting a model wherein childhood personality traits exert their influence on the development of intentions to use alcohol through the development of these more proximal cognitions.

Keywords: Personality, children, alcohol intentions, attitudes, subjective norms

Alcohol is a widely accepted and licit substance that children as young as 3 years old can recognize (Spiegler, 1983). Early use by children and adolescents is associated with adult alcohol abuse (Grant & Dawson, 1997; Newcomb & Bentler, 1988). Although there has been considerable research on contextual, family and peer influences (Andrews, Hops & Duncan, 1997; Andrews, Hops, Tildesley & Li, 2002; Brook, Whiteman, Nomura, Gordon, & Cohen, 1988; Duncan, Duncan, & Hops, 1994; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992), there has been less examination of the influence of young children’s personality traits and cognitions on the development of alcohol use (Tarter, 1988; Tarter et al., 1999). In the present study, we examined whether the influence of two personality traits, hostility and sociability, on the development of intentions regarding future alcohol use was mediated by attitudes and subjective norms. Both traits were assessed by teacher’s ratings. Hostility was defined as physical and relational aggression, and associating with misbehaving children; sociability was defined as a combination of social competence, energy, and popularity. This model was tested on a community sample of young children participating in an ongoing longitudinal study, the Oregon Youth Substance Use Project (OYSUP; Andrews, Tildesley, Hops, Duncan, & Severson, 2003; Severson, Andrews, & Walker, 2003). The data reported here are from the first four years of the project following children from the 1st through the 5th grade until they were in the 4th through the 8th grade. Although few children in 1st through 8th grades have experimented with alcohol, during this period they develop intentions regarding their future use of alcohol.

During the elementary-school years, children develop the precursors of their adult personality traits (Wills, DuHamel, & Vaccaro, 1995). Hostility and sociability have clear counterparts in infant temperament, personality in middle childhood, and personality in adulthood, and therefore are well-suited for study in this age range (Mervielde & Asendorpf, 2000). Hostility reflects the negative emotionality, activity, and reactivity found in all temperament models. Some theories of temperament explicitly include sociability as a dimension (e.g., Buss & Plomin, 1984), and all incorporate an aspect of social approach versus withdrawal or fearfulness. These two traits share similarities with two of the four traits of middle childhood proposed by Shiner (2000): hostility corresponds to (lack of) “agreeableness,” and sociability corresponds to “surgent engagement.” Moreover, hostility and sociability are important features of classroom behavior that reflect the social adaptation of the child to the school setting. Hostility and sociability also have their counterparts in adult personality. In the Big Five model, hostility is primarily associated with the negative pole of Agreeableness, and sociability is primarily associated with Extraversion (Angleitner & Ostendorf, 1994).

Personality traits comprising “difficult temperament,” which includes aspects of hostility, (Windle, 1991), have been associated with numerous adolescent problem behaviors including alcohol use (e.g., Caspi et al., 1997; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Gerrard, Gibbons, Benthin & Hessling, 1996; Shoal & Giancola, 2003; Wills et al.,1995; Zuckerman 1994). Associations have been found between early childhood aggressiveness and later alcohol consumption (e.g., Block, Block, & Keyes, 1988; Boyle et al., 1993; Brook et al.,1986; Kellam, Brown, & Fleming, 1982). For example, the Woodlawn study examined antecedents of substance use in an entire population of first grade children (Kellam et al.,1982; Kellam, Simon, & Ensminger, 1983). For boys, but not for girls, aggressiveness was prospectively related to teenage alcohol use. Comparable findings were obtained in the Ontario Child Health Study in which teacher-assessed conduct disorder (physical violence and violation of social norms) in children as young as 8 years old was predictive of alcohol use four years later (Boyle et al., 1993). Accordingly, it was hypothesized here that more hostile children would be more likely to develop stronger intentions to use alcohol, and that hostility may be a more important predictor for boys than girls.

In most studies, higher levels of sociability have been associated with more use of substances (e.g., Brook, Whiteman, Gordon, & Cohen, 1986; Chassin et al., 1993; Jessor & Jessor, 1977), although lower levels of sociability have predicted more substance use in some studies (Tarter, 1988; Tarter, Sambrano, & Dunn, 2002; Wills, Vaccaro, & McNamara, 1994). Compared to substances such as marijuana or cigarettes, alcohol is relatively normative for adults and older adolescents and is an accepted part of social occasions. Therefore, in the present study, it was hypothesized that higher levels of sociability would be associated with increasing intentions to use alcohol in the future.

According to the Theories of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1988; 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), intentions are determined by attitudes and subjective norms (and, in the Theory of Planned Behavior, by perceived behavioral control), and intentions predict subsequent behavior (Armitage & Conner, 2001). Children’s intentions predict their subsequent alcohol use. For example, Webb, Baer, Getz, & McKelvey (1996) demonstrated that children’s intentions assessed in the 5th grade predicted their levels of actual alcohol use in the 7th grade. Using OYSUP data, Andrews et al. (2003) showed that intention in the 1st through 5th grade was related to initiation of alcohol use two years later. Pierce, Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, & Merrit (1996) conceptualized intentions as the first step in the acquisition of substance use. In a cross-sectional study, Marcoux and Shope (1997) found that attitudes and subjective norms were significant predictors of intentions to drink alcohol among 5th through 8th grade adolescents. Similarly, Webb, Baer, & McKelvey (1995) demonstrated that attitudes and subjective norms were predictors of intentions to use alcohol for 5th and 6th grade children. Using OYSUP data, Andrews, Hampson, Tildesley & Peterson (2002) showed that attitudes mediated by intentions predicted subsequent initiation of alcohol and cigarettes, and attitudes correlated with alcohol use in a survey of rural New Hampshire elementary school children (Stevens, Youells, Whaley, & Linsey, 1991). Therefore, in the present study, the development of attitudes and subjective norms regarding alcohol were expected to predict the development of alcohol intentions.

The Theories of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior also propose that attitudes and subjective norms are influenced by more distal factors such as personality traits (Ajzen, 1988; Connor & Abraham, 2001). However, previous studies conducted with young children have not examined the influence of personality traits on the prediction of alcohol-use cognitions. We predicted that hostility and sociability would be positively related to attitudes, defined as children’s social images of other children who use alcohol (Andrews & Peterson, 2004; Gibbons, Gerrard, & Lane, 2003). Hostile children may have favorable social images of children who use alcohol because they see it as a desirable form of misbehavior. Sociable children enjoy being popular, so activities they believe are likely to increase their positive social images may be viewed favorably.

We also predicted that hostility and sociability would be positively related to subjective norms. To assess subjective norms, descriptive rather than prescriptive norms were used because young children’s parents and peers (their primary social influences) are unlikely to actively want them to drink alcohol (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990). Hostile children are more likely to be marginalized and therefore to spend time with other deviant peers (Dishion, 1990) and deviant children are more likely to engage in problem behaviors, including using alcohol (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). More sociable children are likely to be exposed to higher levels of alcohol use because they spend more time interacting with others and alcohol use is normative among older teens and adults. Accordingly, we predicted that more sociable children and more hostile children are exposed to higher levels of alcohol use by their peers (both actual and claimed), resulting in higher peer-based descriptive norms.

Using data from OYSUP, we tested a mediational model of personality traits and cognitions from the Theory of Reasoned Action to predict intentions to use alcohol. Childhood personality traits (sociability and hostility assessed by teachers’ ratings of classroom behaviors) were expected to influence the development of intentions to drink alcohol as teenagers and as adults through the mediating mechanisms of developing attitudes and subjective norms. Previous analyses of the OYSUP data established that children’s intentions to drink alcohol increased over time, and intentions predicted subsequent initiation of alcohol use (Andrews et al., 2003). In the present study, consistent with the Theory of Reasoned Action, it was predicted that this increase in intentions would be predicted by children’s increasingly favorable attitudes and increasing subjective norms.

Analyses of the OYSUP data (Andrews et al., 2003), and other studies (Cohen, Brownell & Felix, 1990; Grady, Gersick, Snow, & Kenssen, 1986), have shown that boys initiate alcohol use at a younger age than girls, but that girls’ alcohol use increases faster over time than does boys’. Gender differences on personality variables in children indicate that boys are likely to be more hostile and girls are likely to be more sociable (Shiner, 2000). In addition, Kellam and colleagues (Kellam et al., 1982; 1983) showed a relation between hostility in childhood and subsequent alcohol use in adolescence, only for boys. Accordingly, gender was included as a predictor in the models tested here.

Method

Design

In a cohort-sequential design, five grade cohorts (1st through 5th graders at the first assessment) were assessed annually over four years (T1 - T4), until they were in the 4th through 8th grades.

Participants

One thousand and seventy-five children from 15 elementary schools in one school district in Western Oregon serving a predominantly working class community participated in the study. An average of 215 students in each of the 1st through 5th grades participated at T1 with an even distribution by gender (50.3% female; n = 528). At T1 the average age was 9 years (SD = 1.45). The racial/ethnic composition of this sample was 86% Caucasian, 7% Hispanic, 1% Afro-American, and 2% each of Asian/ Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaskan native, and other or mixed race/ethnicity. Approximately 7% of mothers and 11% of fathers had not obtained a high school diploma. Forty percent of the sample was eligible for a free or reduced lunch, an indicator of low family income.

A detailed description of the sampling procedure and representativeness of the sample is given in Andrews et al. (2003). In brief, the children were representative of other children in the school district in terms of race/ethnicity and participation in the free or reduced lunch program, but had slightly higher test scores in reading and math. Participants were similar to children across the state in their substance use. Fifty-four children who participated in the study at T1 did not participate in the T4 assessment (5.0% of the total sample). Attrition between assessments was highest between the first and second assessment (3.7%). A comparison of the children who participated in the study at T4 with children who did not participate at T4 showed no differences at T1 on intentions to use alcohol or on attitudes toward using this substance. Participants were also similar to non-participants in grade, gender, race/ethnicity, proportion who received a free or reduced lunch, and achievement test scores at T1.

The sample analyzed here consisted of the 1,049 children who participated at any of the four assessments whose teachers completed a questionnaire assessing their behavior at T1. Five hundred and twenty-one of these children were boys and 528 (50.3%) were girls. These children did not differ from those in the total sample on the above variables.

Procedures

Assessment procedures are described by Andrews et al. (2003). The 1st through 3rd grade assessment was an individual interactive structured interview, whereas older children answered paper and pencil surveys within a group setting.1 All T1 assessments and T2 through T4 assessments for students who remained within the district were conducted at school during the school day. Teachers’ ratings of the children’s behavior (T1 assessment) were made during the second half of the school year (January - May) ensuring that the teachers had time to get to know the children.

Measures

Attitudes

All the children were asked whether kids who drink alcohol are “liked by other kids,” are “exciting,” and are “cool or neat” (“No” = 0, “Maybe” = 1, or Yes” = 2), and the three items were summed. Andrews and Peterson (2004) showed that a scale comprised of these items was stable, valid and unidimensional.

Subjective norms

To assess peer-based descriptive norms, 1st through 3rd graders were shown a picture of alcoholic beverages and asked “Do any kids in your neighborhood or at school drink this?” and “Do your friends ever drink this?” (“No” or “Maybe” = 0, “Yes” = 1). The responses to the two items (r = .39 across assessments) were summed. Fourth through 8th graders were asked “How many of the kids at school or in the neighborhood have tried a drink of alcohol (beer, wine, or hard liquor)?” (“None” = 0, “Some”, “Most” or “All” = 1), and “Do you have any friends who drink alcohol?” (“Yes” = 1, “No” = 0). Responses were summed across the two items (4th and 5th graders: r = .26, across assessments; 6th though 8th graders: r = .55, across assessments). Convergent and discriminate correlations among the two items assessing norms and the three items assessing attitudes were examined for different grades at each time of assessment. The correlations among items assessing the same construct were consistently higher (mean convergent r for attitude items = .40, mean convergent r for norm items = .34) than the correlations between items assessing divergent constructs (mean divergent r = .14).

Intentions

First through 3rd graders were shown a picture of alcoholic beverages and were asked “Do you think you would drink this when you are a teenager?” and “Do you think you would drink this when you are grown-up?” (“No” = 0, “Maybe” = 1, or “Yes” = 2). Responses to the two items were summed (r = 0.45). For the older children, intentions to drink alcohol was measured by two items: “Do you think you would drink alcohol (beer, wine, or hard liquor) when you=re a teenager (4th and 5th graders) or when you’re in high school (6th through 8th graders)?” and “Do you think you would drink alcohol (beer, wine, or hard liquor) when you=re a grown-up?” (“No” = 0, “Maybe” = 1, or “Yes” = 2). Responses were summed across the two items (r = 0.47).

Trying alcohol

All participants were asked if they have ever tried alcoholic beverages (Yes or No).

Teachers= Ratings

The Walker McConnell test of children’s social skills (Walker & McConnell, 1995) is comprised of three scales in which the teacher rates the frequency (1 = “Never,” 5 = “Frequently”) of observing the child demonstrate specific social skills in interactions with peers (7 items, alpha = .92), with teachers (6 items, alpha = .91), and the frequency of behaviors reflecting adjustment to school (9 items, alpha = .96). The 3-item Harter social acceptance sub-scale (Harter, 1985) assesses popularity/unpopularity with peers using bipolar items in which the rater chooses one pole as the more accurate and rates it as “Really true” or “Sort of true” for the child (alpha = .95). The 9 items of the Achenbach withdrawal scale (Achenbach, 1991) describe various withdrawn, depressed and introverted behaviors which are rated as “Not,” “Somewhat or sometimes,” or “Very or often” true of the child (alpha = .87). The Crick aggression scales (Crick, 1996) measure relational aggression (7 items, alpha = .94), overt aggression (4 items, alpha = .94), and prosocial behavior (4 items, alpha = .94) on a 5-point scale (1 = “Never true,” 5 = “Almost always true”). Five items from the Oregon Youth Study (Patterson et al., 1992) assess the frequency with which the child performs aggressive or delinquent acts, behaves well, or is a leader in their school on a 5-point rating scale (1 = “Never,” 5 = “Always”, alpha = .79).

In addition, teachers rated how hard the child was working and how much the child was learning (single items) compared to typical students of the same age, using a 7-point scale (1 = “Much less,” 4 = “About average,” 7 = “Much more”). They also described the child by responding “Yes” or “No” to three statements: “Seems to understand things,” “Is liked by everyone,” and “Is especially nice”. They rated the popularity of the student on a 4-point scale (1 = “Very popular with peers,” 4 = “Mostly rejected by peers”).

Items across all scales were factor analyzed using Principal Components followed by Varimax rotation. Solutions for two, three, four, five, and six factors were examined. The two-factor solution generated independent and interpretable factors that accounted for 52.3% of the variance and preserved the integrity of the original scales. The first factor was labeled “sociability” and the second factor was labeled “hostility”. To obtain orthogonal scales, we selected ten high-loading, factor-pure marker items for each factor (see Table 1). Confirmatory factor analysis using the marker items as indicators of the latent constructs of hostility and sociability demonstrated acceptable fit, χ2 (143, N = 1049) = 417.97, root mean square error of approximation (RSMEA) = .043 (90% CI = .038, .048), CFI = .98. Cronbach’s alpha was .93 for both resulting traits scales, and the Pearson product moment correlation between them was - .16.

Table 1.

Items Comprising the Hostility and Sociability Scales

| Hostility |

| Crick relational aggression items |

| When this child is mad at a peer, she or he gets even by excluding the peer from his or her clique or peer group |

| This child spreads rumors or gossips about some peers |

| When angry at a peer, this child tried to get other children to stop playing with the peer or to stop liking the peer |

| This child tries to get others to dislike certain peers by telling lies about the peers to others |

| This child threatens to stop being a peer’s friend in order to hurt the peer or to get what she/he wants from the peer |

| This child tries to exclude certain peers from peer group activities |

| Crick overt aggression items |

| This child hits, shoves, or pushes peers |

| This child intitiates or gets into physical fights with peers |

| This child tires to dominate or bully peers |

| Oregon Youth Study item |

| How often does this student associate with kids who misbehave in school? |

| Sociability |

| Walker/McConnell items |

| Other children seek the child out to involve him/her in activities |

| Plays or talks with peers for extended periods |

| Initiates conversations with peers in informal situations |

| Keeps conversations with peers going |

| Invites peers to play or share activities |

| Achenbach withdrawal items (reversed) |

| Would rather be alone than with others |

| Underactive, slow moving, or lacks energy |

| Withdrawn, doesn’t get involved with others |

| Harter social competence item |

| Has a lot of friends |

| OYSUP item |

| How would you characterize this student? (very popular with peers, average in popularity with peers, mostly ignored by peers, mostly rejected by peers) |

Statistical Analysis

We used latent growth modeling (LGM; Muthén, 1991) to test several sequential models leading to a final model relating sociability and hostility to intentions to drink alcohol through the mediating constructs of attitudes and norms. All models were analyzed with Mplus, Version 3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2004) with the maximum likelihood method, using the EM algorithm for missing data (Little & Rubin, 1987). LGM takes advantage of the longitudinal dataset by allowing for the examination and prediction of individual and average change across the four assessments. LGM provides estimates of the average (group) developmental trajectory, including both the intercept (often termed the level) and slope (rate of change over time), and the variance or individual differences in these parameters. Intercepts and slopes may both be predictors and predicted. Within the models, intentions, attitudes and norms were developmental trajectories, and sociability and hostility at T1 were exogenous observed variables.2 Grade at T1 and whether or not the child reported having tried alcohol at T1 were also included as exogenous variables in all the models to control for their effects (Gibbons et al., 2003), and all the exogenous variables were allowed to correlate. We used multiple-sample analysis to examine gender differences in the predictive models.

Analyses were done sequentially. First, separate growth models were tested for intentions, attitudes and subjective norms to examine the developmental function that optimally assessed change for each variable over the four assessments. Within each growth model, the intercept and slope (latent constructs) were based on four indicators, the variable at each of four assessments. Across all three models, the factor loadings of the intercept on all indicators (assessments) were set to 1. Factor loadings of the linear slope on the four indicators were set sequentially to 0, 1, 2, and 3.

To answer our substantive research question, two subsequent models were fit to the data. For each model, several steps were followed. First, using multiple-sample analysis, an initial model was estimated which included all hypothesized structural paths and correlations between all indicators. Paths and correlations were initially fixed to be equal between genders but were freed iteratively if a gender difference was indicated through an examination of each modification index. If a structural path was significant (p <.05) for either gender, it was included in the final model. Paths from grade and trying alcohol at T1 to intercepts and slopes were retained in all models, but other non-significant structural paths were eliminated. Correlations between indicators at the same or adjacent assessments were included in the model if indicated by modification indices. A final model, dropping non-significant paths, was then fitted to the data.

In model 1, grade, alcohol use at T1, hostility, and sociability were specified as exogenous variables in the prediction of the initial level (intercept) and growth (slope) of intentions to drink alcohol in the future. In model 2, the intercept and slope of attitudes and subjective norms predicted the intercept and slope of intentions and the effects of the exogenous variables, hostility and sociability on the intercept and slope of attitudes and subjective norms were estimated. To test for mediation, following recommendations by Holmbeck (1997) and Frazier, Tix, & Barron (2004), the fit of model 2 was compared under two conditions, separately for each trait: (a) where the direct path from the personality trait to the outcome was constrained to zero for each gender, and (b) where the direct path was unconstrained for each gender.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

At T1, girls (M = .09, SD = .73) were significantly higher in sociability than boys (M = -.09, SD = .83), t (1047) = -3.74, p = < .05, (95% CI: -.28, -.09). For hostility, the difference between boys (M = .01, SD = .78) and girls (M = -.02, SD = .80) was not significant, t (1047) = .60, ns. The means and standard deviations for attitudes, subjective norms, and intentions at each time of assessment are shown separately for boys and girls in Table 2. There were no differences between boys and girls in their mean attitudes, t (1047) = 1.92, ns, and subjective norms, t (1047) = 1.23, ns, collapsed across times of assessment, but boys had higher intentions than did girls, t (1047) = 3.95, p <.001. The correlation between attitudes and subjective norms was .16 for T1, .12 for T2, .22 for T3, and .36 for T4. The correlation between attitudes and intention was .26 for T1, .31 for T2, .35 for T3 and .45 for T4. The correlation between subjective norms and intentions was .22 for T1, .29 for T2, .39 for T3 and .47 for T4.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for TRA Constructs for Boys and Girls at Each Time of Assessment

| Boys | Girls | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | Subjective Norms | Intentions | Attitudes | Subjective Norms | Intentions | ||||||||

| Assessment | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| T1 | .43 | .92 | .11 | .36 | .65 | .98 | .48 | .83 | .08 | .31 | .41 | .75 | |

| T2 | .41 | .94 | .43 | .68 | .64 | .97 | .43 | .79 | .33 | .61 | .50 | .84 | |

| T3 | .42 | .93 | .62 | .79 | .75 | 1.05 | .52 | .95 | .54 | .75 | .58 | .87 | |

| T4 | .50 | 1.05 | .80 | .83 | .86 | 1.03 | .61 | 1.10 | .86 | .85 | .78 | 1.03 | |

| All Times | .43 | .64 | .48 | .49 | .73 | .78 | .51 | .62 | .44 | .47 | .55 | .65 | |

Latent Growth Curve Models for Intentions, Attitudes and Subjective Norms

To model growth in intentions to drink alcohol, a linear model best fit the data, χ2 (5, N =1049) = 17.43, p <.01, RMSEA = .048 (90% CI = .025, .074). Both the intercept (M = .49) and slope (M = .10) differed significantly from zero (p <.001) with significant variance for both (p <.001). A linear growth model best fit the data for growth in attitudes, χ2 (5, N =1,049) = 9.74, p = .08, RMSEA = .030 (90% CI = .000, .058) and means (intercept M = .42; slope M = .03, p <.001) and variances differed significantly from zero (p <.001). A model with both a linear and a quadratic factor (with loadings of 0, 1, 4, and 9 on indicators) best fit the data for growth in subjective norms, χ2 (1, N =1,049) = 4.55, p <.05, RMSEA =.058 (90% CI = .013, .115). The means of the intercept (M = .10, p <.001), and linear slope (M = .26, p <.001) varied significantly from zero, but the quadratic factor did not (-.05, ns). The variance of the intercept was marginally significant (p <.10), and the variances of the linear slope and of the quadratic factor were significant (p <.001), indicating relatively more change in subjective norms in later assessments for some children.

Model 1: The Prediction of Growth in Intentions from Hostility and Sociability (Direct Paths)

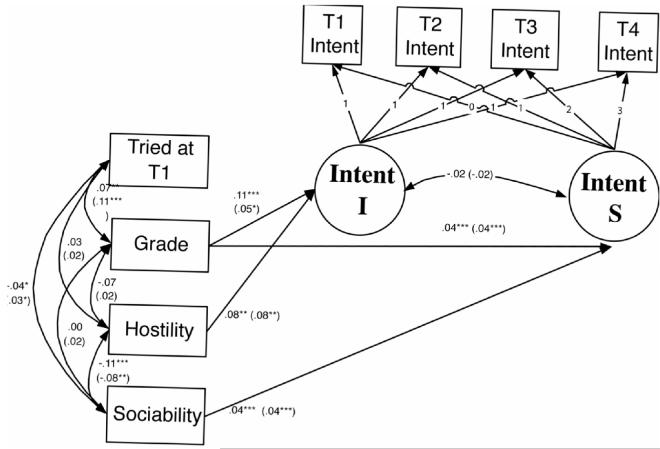

In model 1, the paths from the exogenous variables of hostility and sociability measured at T1, as well as grade and trying alcohol at T1, to the intercept and slope of intentions were estimated. The final version of model 1 is shown in Figure 1. Grade was not associated with either hostility or sociability. Trying alcohol at T1 was associated with grade for both genders (children in older grades were more likely to have tried alcohol). Trying alcohol at T1 was associated with sociability for both genders but not with hostility. Grade significantly predicted both the intercept and slope of intentions for both genders. Results of the multiple-sample analysis showed that the intercept of intentions was significantly higher for boys than girls (p <.05), but the slope of intentions of girls and boys did not differ. Thus boys had higher intentions to use alcohol than did girls, but the rate of increase in intentions between genders was similar over time. The paths from hostility to the intercept of intentions, and from sociability to the slope of intentions, were significant for both genders suggesting that more hostile children had higher intentions, and the intentions of more sociable children increased faster over time. Two structural paths were not significant for either gender in the initial model, the path from hostility to the slope of intentions, and the path from sociability to the intercept of intentions, and therefore were not estimated in the final model. The fit of the final version of model 1 was adequate, χ2 (38, N = 1,049) = 103.81, p <.001, RMSEA = .057 (90% CI = .044, .071), CFI = .94.

Figure 1.

Model 1: Latent growth model (multiple-sample analysis) of intentions to drink alcohol in which intercept and slope were predicted by sociability and hostility.

NOTE: Hostility, sociability, and grade were assessed at T1, intentions at all four assessments (T1 - T4). Unstandardized estimates are shown separately for boys and girls (girls in parentheses). Only paths significant for one or both genders are shown (* p = <.05, ** p = < .01, *** p = < .001). Intent = intentions, I = intercept, S = slope.

Model 2: The Indirect Paths from Hostility and Sociability to Intentions through Attitudes and Subjective Norms

In model 2, we estimated the paths (a) from the intercept of attitudes and subjective norms to the intercept and slope of intentions, (b) from the slope of attitudes and both the linear and quadratic slopes of subjective norms to the slope of intentions, (c) from the exogenous personality variables to the intercept and slope of attitudes and norms, and (d) from grade and trying alcohol at T1 to the intercept and slopes of attitudes, norms and intentions. Paths from the slopes of attitudes and subjective norms to the intercept of intentions were not estimated since these paths suggest that growth in attitudes and subjective norms between T1 and T4 predict the initial level of intentions at T1, which occurs earlier in time.

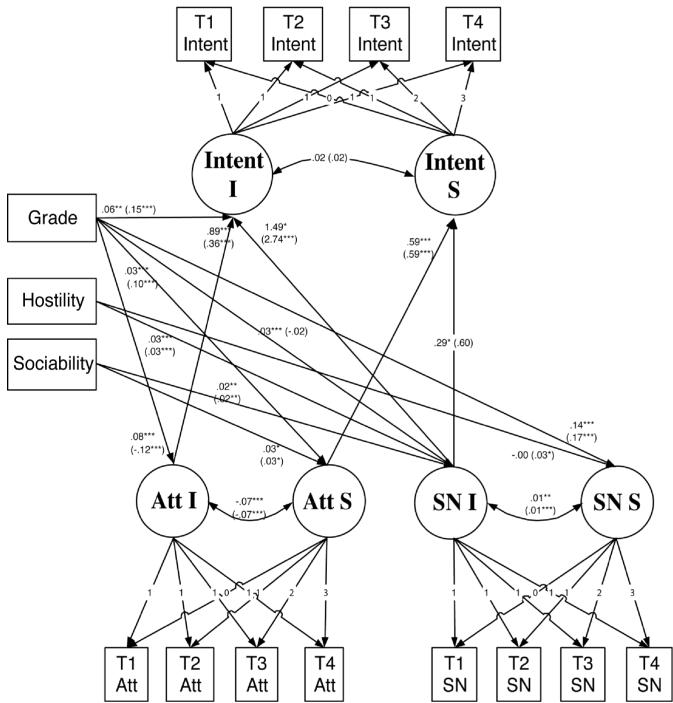

The final model is shown in Figure 2. For simplification, not shown in the figure are the path coefficients between the slopes of norms and attitudes (.01, t = 1.59, ns, for both genders) and the intercepts of norms and attitudes (.02, t = 7.71, p <.001, for both genders). Also for simplification, the quadratic slope of subjective norms is not shown. However, only the effect of grade on the quadratic slope was significant (- .02; t = -6.57, p < .001) for both genders, and the quadratic slope did not predict either the intercept or slope of intentions. This negative relation between the quadratic slope of subjective norms and grade suggests that older children did not increase their subjective norms in the later assessments as much as did younger children. As expected from the Theory of Reasoned Action, for both boys and girls, the intercept of attitudes and the intercept of subjective norms predicted the intercept of intentions, and the slope of attitudes predicted the slope of intentions. However, the slope of norms did not predict the slope of intentions.

Figure 2.

Model 2: Latent growth model (multiple-sample analysis) in which the development of attitudes and subjective norms predicted the development of intentions, and the effects of sociability and hostility on the development of intentions was indirect through the development of subjective norms.

NOTE: Hostility, sociability, grade, and trying alcohol were assessed at T1, intentions, attitudes and subjective norms at all four assessments (T1 - T4). Unstandardized estimates are shown separately for boys and girls (girls in parentheses). Only paths significant for one or both genders are shown (* p = <.05, ** p = < .01, *** p = < .001). Intent = intentions, Att = attitudes, SN = subjective norms, I = intercept, S = slope, Tried at T1 = reported having tried alcohol at the first assessment.

For both boys and girls, grade was positively related to the intercept and slope of intentions, the slope of attitudes and the slope of subjective norms. While for boys, grade was positively related to the intercept of attitudes, for girls, the relation was negative. For boys only, grade predicted the intercept of norms. Trying alcohol at T1 predicted the intercepts of attitudes and norms for both genders but not the slopes. Hostility positively predicted the intercept of subjective norms for both boys and girls. For both boys and girls, sociability positively predicted the intercept of subjective norms and the slope of attitudes. Thus, more hostile and more sociable children had higher initial subjective norms, and more sociable children developed more favorable attitudes over time. The fit of the final version of model 2 (see Figure 2) was adequate, X2 (158, N =1,049) = 375.01, p <.001), RMSEA = .051 (90% CI = .045, .058), CFI = .94.

Tests for Mediation

The significant paths in models 1 and 2 were examined in the context of Baron and Kenney’s (1986) criteria for mediation. First, the predictors (sociability and hostility) must be related to the outcome variables (the intercept and slope of intentions). As shown in model 1, for both genders, sociability was related to the slope and hostility was related to the intercept of intentions. Second, the mediating variables (the intercept and slope of attitudes and subjective norms) must be related to the outcome variables. As shown in model 2, for both genders, the intercept of attitudes and the intercept of subjective norms were related to the intercept of intentions, and the slope of attitudes was related to the slope of intentions. Third, the predictors must be related to the mediating variables. As shown in model 2, for both genders, sociability was positively related to the slope of attitudes, and hostility was positively related to the intercept of subjective norms. Two indirect paths from the personality predictors to intentions indicated potential mediation: the path from hostility to the intercept of intentions through the intercept of norms, and the path from sociability to the slope of intentions through the slope of attitudes. The final criterion for mediation is to demonstrate that the direct path becomes non-significant (or is significantly reduced) when included in the model with the indirect path. In structural equation modeling, this is tested by demonstrating the inclusion of the unconstrained direct path does not improve the fit of the model (Frazier et al., 2004; Holmbeck, 1997).

Both personality influences met the criteria for mediation. For hostility, including the unconstrained direct path from hostility to the intercept of intentions in model 2 did not significantly improve the fit compared to constraining this path to be zero, χ2difference (4, N = 1,049) = .91, ns. Similarly, for sociability, including the unconstrained direct path from sociability to the slope of intentions in the model did not significantly improve the fit compared to constraining this path to be zero, χ2 difference (4, N = 1,049) = 2.28, ns.

To test for possible gender differences in the mediated effects, the significance of the indirect paths for each gender was evaluated using the Sobel test (McKinnon, Warsi, & Dwyer, 1995; Sobel, 1982). The indirect path from hostility to the intercept of intentions through the intercept of norms was significant for boys, Sobel test = 2.874, p = .004, and was marginally significant for girls, Sobel test = 1.952, p = .051. The indirect path from sociability to the slope of intentions through the slope of attitudes was significant for boys and girls, Sobel test = 2.307, p = .021.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the influence of hostility and sociability on the development of elementary school children’s intentions to use alcohol, and to determine whether the influence of these traits was mediated by more proximal determinants of intentions, namely the development of attitudes and subjective norms. The findings were generally consistent with the hypothesized mediational model. For both boys and girls, hostility and sociability were related to the development of intentions through their relations with the development of attitudes and subjective norms. The influence of hostility on the initial level of intentions was mediated by the initial level of subjective norms, and the influence of sociability on the growth of intentions was mediated by the growth of attitudes. The mediated effect of hostility was stronger for boys than girls.

As expected, attitudes, subjective norms, and intentions about alcohol use all increased developmentally. As these children grew older, they developed more favorable social images (attitudes) of children who use alcohol, they believed more of their peers were using alcohol (peer-based descriptive norms), and they were more likely to say that they intended to try alcohol when they were teenagers or adults (intentions). The growth in attitudes and intentions was linear whereas the growth in subjective norms included a quadratic component with significant variance suggesting that some children increased their norms between 5th (elementary school) and 6th (middle school) grades. This increase in subjective norms parallels the increase in experimentation with alcohol use between the 5th and 6th grades found for this sample (Andrews et al., 2003). Alcohol use is markedly more normative in middle school than elementary school.

For boys, and girls to a lesser extent, hostility influenced the initial level of intentions through the initial level of subjective norms (peer-based descriptive norms), supporting the hypothesis that more hostile children are exposed to problem behaviors performed by their peers, of which alcohol use is one (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). More hostile children perceived more of their peers as using (or claiming to use) alcohol and were more likely to have higher intentions to use alcohol themselves. Terry and Hogg (1996) demonstrated that subjective norms influenced intentions only for individuals who identified with the normative reference group for the behavior in question. Our results suggest that hostile children, but not sociable children, identify with their deviant peers.

For both boys and girls, sociability predicted the growth of favorable attitudes toward alcohol use, which in turn were associated with the growth of higher intentions to use alcohol. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that more sociable children develop higher intentions to use alcohol because, as they grow older, they attribute increasingly positive attributes to alcohol users. The characteristics attributed to children who use alcohol (i.e., being perceived as “liked by other kids”, “exciting” and “cool or neat”) are remarkably similar to several of the defining features of sociability as measured in this study (note that both measures were developed independently and empirically). Like the sociable child, the attributes of “popular” and “cool or neat,” capture the interpersonal competence of sociability. Similarly, the attribute of “exciting” captures the disinhibited (i.e., activity and activity initiation) aspects of sociability (see Table 1). Burton, Sussman, Hansen, Johnson and Flay (1989) showed that children whose self-perceptions were similar to the stereotypical images of smokers were more likely to report intentions to smoke. A comparable process may have been observed here: sociable children were more likely to view alcohol use favorably on dimensions consistent with their self-images, and hence sociable children were more likely to intend to use alcohol in the future. The lack of consistency between the characteristics of hostility and the attitude attributes may explain why attitudes did not mediate the influence of hostility on intentions. Children’s self-perceptions of personality become more differentiated with age (Mervielde & Asendorpf, 2000). Therefore, as sociable children develop, their self-perceptions are increasingly likely to match their social images of alcohol users. Such a mechanism is consistent with the finding that sociability did not predict the initial level of attitudes but did predict the growth in attitudes.

To our knowledge, there are no other longitudinal studies demonstrating that the influence of childhood personality traits on children’s intentions to use alcohol are mediated by cognitions. However, our study of children is consistent with an earlier study of adults, in which the effects of extraversion, neuroticism, and conscientiousness on intentions to engage in healthy behaviors were fully or partially mediated by cognitions from the Theory of Planned Behavior (Conner & Abraham, 2001). These findings, together with the present study, strengthen the case for cognitions mediating the effects of personality traits on intentions.

Limitations of the present study include adapting the measures of attitudes, norms, and intentions to make them suitable for children as young as 1st grade, and not narrowly specifying and matching these measures as is recommended by Ajzen and Fishbein (1991). The associative latent growth models examined here show that developing attitudes and norms are related to developing intentions, over time. However, associative models do not presume a causal influence, but merely an association, similar to that of a correlation, but within a longitudinal perspective. Thus, the observed growth in attitudes and subjective norms could be the cause or the consequence of the growth of intentions, or developmental changes in all three constructs could be the result of the influence of another variable. The models studied here examined growth in intentions to use alcohol as the outcome. Future research to establish whether growth in intentions to use alcohol predicts subsequent levels of actual alcohol use would be desirable.

These findings have a number of implications for interventions for young children to prevent the development of early alcohol use. We have shown that cognitions regarding intentions to use alcohol in the future develop during elementary school. Therefore prevention programs that delay the development of these intentions are appropriate for children in the early elementary years. These prevention programs could target changing social images, making children’s social images of alcohol users less favorable. Our findings suggest that children who are most at risk are those high in sociability. Since girls are more sociable than boys, they may be at particular risk of developing increasingly favorable attitudes to alcohol, suggesting that highly sociable girls could be the focus of such interventions. Prevention programs should also target correcting children’s peer-based descriptive norms, which are typically overestimations of actual use (Unger, Rohrbach, Howard-Pitney, Ritt-Olson, & Mourrapa, 2001). We showed that children’s hostility influenced intentions to drink alcohol through subjective norms. This suggests the importance of targeting the peer-based descriptive norms of more hostile children for prevention programs. An important question for future research is whether the same mediational models would apply for less normative substances such as cigarettes or marijuana. Alcohol may be a special case because age-appropriate, moderate alcohol use is widespread and accepted. Intentions to use alcohol when older may therefore develop in a different way than intentions to use less normative substances when older.

In conclusion, this study has advanced our understanding of the influence of sociability and hostility on the development of young children’s intentions to use alcohol. The findings from this study support a model in which hostility and sociability influence the development of intentions to use alcohol through the associations with the development of attitudes and subjective norms. This study illustrates a methodology for future testing of mediational developmental models using latent growth modeling.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant DA10767 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Martha Hardwick and the assessment staff, for helping with data collection, and Christine Lorenz for manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

No significant differences on the alcohol variables between the assessment methods were found in a separate study of 60 4th graders (see Andrews et al., 2003). A comparison of stability coefficients for OYSUP children in grades 3 at T1 and grade 4 at T2 (i.e., the transition from interview one year to questionnaire the next) demonstrated moderate to high stability on the alcohol measures: attitude, r = .26; % agreement for intention = 70.3%, subjective norms = 63.2%, trying = 81.6%; and trying without parental consent = 98.6%.

We chose not to examine the latent growth of hostility and sociability or to associate trait growth with growth of cognitions. There is mounting evidence of the stability of the broad personality traits of middle childhood and of correlations of these early measures with life outcomes 10 - 20 years later (Shiner, Masten, & Roberts, 2003). Therefore, we treated hostility and sociability as stable variables and examined the influence of their levels at T1 on the subsequent development of attitudes, subjective norms, and intentions.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Teacher=s Report Form and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality and behavior. Open University Press; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Peterson M. The development of attitude toward substance use: A Guttman scaling approach. 2004. Manuscript in preparation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Andrews JA, Hampson SH, Tildesley E, Peterson M. The prospective relation between cognitions and use of cigarettes and alcohol: An elementary school sample; Poster presented to Society for Prevention Research; Seattle, Washington. 2002, May. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Duncan SC. Adolescent modeling of parent substance use: The moderating effects of the relationship with the parent. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:259–270. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.11.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Tildesley E, Li F. The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychology. 2002;21:349–357. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Duncan SC, Severson HH. Elementary school age children’s future intentions and use of substances. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:556–567. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angleitner A, Ostendorf F. Temperament and the Big Five factors of personality. In: Halverson CF Jr., Kohnstamm GA, Martin RP, editors. The developing structure of temperament and personality from infancy to adulthood. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40:471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block J, Block JE, Keyes S. Longitudinally foretelling drug usage in adolescence: Early childhood personality and environmental precursors. Child Development. 1988;59:336–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb01470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MH, Offord DR, Racine YA, Fleming JE, Szatmari P, Links P. Predicting substance use in early adolescence based on parent and teacher assessments of childhood psychiatric disorder: Results from the Ontario Child Health Study follow-up. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993;34:535–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Gordon AS, Cohen P. Dynamics of childhood and adolescent personality traits and drug use. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:403–414. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Nomura C, Gordon AS, Cohen P. Personality, family, and ecological influences on adolescent drug use: A developmental analysis. Journal of Chemical Dependency Treatment. 1988;1(2):123–161. [Google Scholar]

- Burton D, Sussman S, Hansen WB, Johnson CA, Flay BR. Image attributions and smoking intentions among seventh grade students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1989;19:656–664. [Google Scholar]

- Buss A, Plomin R. Temperament: Early developing personality traits. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Begg D, Dickson N, Harrington HL, Langley J, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Personality traits predict health-risk behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1052–1063. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pillow DR, Curran PJ, Brooke SG, Molina, Barrera M., Jr. Relation of parental alcoholism to early adolescent substance use: A test of three mediating mechanisms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:3–19. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Reno RR, Kallgren CA. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RY, Brownell KD, Felix MRJ. Age and sex differences in health habits and beliefs of schoolchildren. Health Psychology. 1990;9:208–224. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner M, Abraham C. Conscientiousness and the Theory of Planned Behavior: Toward a more complete model of the antecedents of intentions and behaviors. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1547–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Conner M, Sparks P. The theory of planned behavior and health behaviors. In: Conner M, Norman P, editors. Predicting health behavior: Research and practice with social cognition models. Open University Press; Buckingham, UK: 1996. pp. 121–162. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children’s future social adjustment. Child Development. 1996;67:2317–2327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ. The peer context for troublesome child and adolescent behavior. In: Leone PE, editor. Understanding troubled and troubling youth. Sage Publications; Beverly Hills, CA: 1990. pp. 128–153. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Hops H. The effects of family cohesiveness and peer encouragement on the development of adolescent alcohol use: A cohort-sequential approach to the analysis of longitudinal data. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:88–597. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intentions, and behavior. Wiley; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing a mediator and moderator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Benthin AC, Hessling RM. A longitudinal study of the reciprocal nature of risk behaviors and cognitions in adolescents: what you do shapes what you think and vice versa. Health Psychology. 1996;15:344–354. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Lane DJ. A social reaction model of adolescent health risk. In: Suls JM, Wallston K, editors. Social psychological foundations of health and illness. Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2003. pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Blanton H, Russell DW. Reasoned action and social reaction: Willingness and intention as independent predictors of health risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1164–1180. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady K, Gersick KE, Snow DL, Kessen M. The emergence of adolescent substance use. Journal of Drug Education. 1986;16(3):203–220. doi: 10.2190/ELAR-N5PW-BH6A-VD39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–10. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:599–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the self-perception profile for children. University of Denver; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Keating DP. Adolescent thinking. In: Feldman SS, Elliot GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1990. pp. 54–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Brown CH, Fleming JP. Social adaptation to first grade and teenage drug, alcohol and cigarette use. Journal of School Health. 1982;52:301–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1982.tb04627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Simon MB, Ensminger ME. Antecedents in first grade of teenage substance use and psychological well-being: A ten-year community wide prospective study. In: Riks DF, Dohrenwend BS, editors. Origins of psychopatholgy. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Marcoux BC, Shope JT. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to adolescent use and misuse of alcohol. Health Education Research. 1997;12:323–331. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995;30:41062. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mervielde I, Asendorpf JB. Variable-centred and person-centred approaches to childhood personality. In: Hampson SE, editor. Advances in personality psychology, volume one. Psycholology Press; Hove, E.Sussex: 2000. pp. 37–76. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO. Analysis of longitudinal data sets using latent variable models with varying parameters. In: Collins LM, Horn JL, editors. Best methods for the analysis of change: Recent advances, unanswered questions, future directions. American Psychological Association; Washington, CD: 1991. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 3rd ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2004. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Impact of adolescent drug use and social support on problems of young adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(1):64–75. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. A social interactional approach: IV. Antisocial boys. Castalia Publishing Company; Eugene, OR: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Merritt RK. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychology. 1996;15:355–361. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L, Greene D, House P. The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1977;13:279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Severson HH, Andrews JA, Walker HM. Screening and early intervention for antisocial youth within school settings as a strategy for reducing substance use. In: Romer D, editor. Reducing adolescent risk: Toward an integrated approach. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL. Linking childhood personality with adaptation: Evidence for continuity and change across time into late adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:310–325. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL, Masten AS, Roberts JM. Childhood personality foreshadows adult personality and life outcomes two decades later. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1145–1170. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoal GD, Giancola PR. Negative affectivity and drug use in adolescent boys: Moderating and mediating mechanisms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:221–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology 1982. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegler DL. Children’s attitudes toward alcohol. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1983;44:545–552. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1983.44.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M, Youells F, Whaley R, Linsey S. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol use in a survey of rural elementary school students: The New Hampshire study. Journal of Drug Education. 1991;21(4):333–347. doi: 10.2190/NAKC-93GL-G59T-LUL8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE. Are their inherited behavioral traits that predispose to substance abuse? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:189–196. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Sambrano S, Dunn MD. Predictor variables by developmental stages: A Center for Substance Abuse Prevention multisite study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:S3–S10. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.16.4s.s3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Giancola P, Dawes M, Blackson T, Mezzich A, Clark DB. Etiology of early age onset substance use disorder: A maturational perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:657–683. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry DJ, Hogg MA. Group norms and the attitude-behavior relationship: A role for group identification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22:776–793. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Rohrbach LA, Howard-Pitney B, Ritt-Olson A, Mourrapa M. Peer influences and susceptibility to smoking among California adolescents. Substance Use and Misuse. 2001;36:551–571. doi: 10.1081/ja-100103560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker HM, McConnell SR. Walker-McConnell Scale of Social Competence and School Adjustment. Singular Publishing Group; San Diego, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Webb JA, Baer PE, McKelvey RS. Development of a risk profile for intentions to use alcohol among fifth and sixth graders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1772–778. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199506000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb JA, Baer PE, Getz G, McKelvey RS. Do fifth graders= attitudes and intentions toward alcohol use predict seventh grade use? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1611–1617. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199612000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, DuHamel K, Vaccaro D. Activity and mood temperament as predictors of adolescent substance use: Test of a self-regulation mediational model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:901–916. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Vaccaro D, McNamara G. Novelty seeking, risk taking, and related constructs as predictors of adolescent substance use: An application of Cloninger’s theory. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1994;6:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. The difficult temperament in adolescence: Associations with substance use, family support, and problem behaviors. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1991;47:310–315. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199103)47:2<310::aid-jclp2270470219>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Impulsive, unsocialized sensation seeking: The biological foundations of a basic dimension of personality. In: Bates JE, Wachs TD, editors. Tempermaent: Individual differences at the interface of biology and behavior. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1994. pp. 219–255. [Google Scholar]