Abstract

There is evidence that the classification of “psychopath” captures a heterogeneous group of offenders. Although several studies have provided evidence for two distinct psychopath subtypes, these studies have inadequately addressed potentially important ethnic differences. A recent taxonomic study found evidence for primary and secondary psychopath subgroups in a sample of European American offenders (Swogger & Kosson, 2007). The present study used cluster analysis to attempt to replicate those findings in a sample of African American offenders. Results confirm the presence of primary and secondary subtypes in African Americans. However, differences between the clusters obtained in the present and previous studies suggest that caution is warranted in generalizing offender taxonomies across ethnicity.

Psychopathy is a personality disorder that has been studied extensively among criminal offenders and is increasingly used in legal proceedings (Hare, 2003; Walsh & Walsh, 2006). It is associated with a variety of negative criminal justice outcomes (Douglas, Vincent, & Edens, 2006; Leistico, Salekin, DeCoster, & Rogers, 2008; Salekin, Rogers, Ustad, & Sewell, 1998), and with specific performance deficits in laboratory studies of emotional and cognitive function (for reviews, see Blair, 2006; Hare, 1998; Hiatt & Newman, 2006). Criminal offenders are a markedly heterogeneous group (Clements, 1996), and there is growing evidence that the classification of “psychopath” may also capture several subgroups of offenders (Poythress & Skeem, 2006). Indeed, studies of European American and polyethnic samples (Skeem et al. 2004; Swogger & Kosson, 2007) indicate that psychopathy can be parsed into at least two distinct subgroups. Whether these subdivisions extend to African American offenders, however, is unknown. The present study is the first to examine the extent to which meaningful subgroups of psychopathic offenders can be identified in a sample of African American county jail inmates.

The appreciation of heterogeneity among criminal offenders with regard to personality traits may inform our understanding of criminal behavior (Brinkley, Newman, Widiger, & Lynam, 2004). Among the personality-based constructs related to the classification of criminal offenders, psychopathy is likely one of the most important, and both research and theory suggest an important distinction between primary and secondary psychopathy (Karpman, 1948; Lykken, 1995). Primary psychopaths are said to exhibit higher levels of the interpersonal and affective traits consistent with Cleckley’s (1976) conceptualization of the disorder, such as a superficial and manipulative interpersonal style, lack of remorse, lack of empathy, and shallow emotions. Secondary psychopaths are purportedly characterized by considerable impulsivity, as well as greater anxiety and negative affectivity and a higher level of substance abuse than are primary psychopaths (Poythress & Skeem, 2006; Vassileva, Kosson, Abramowitz, & Conrod, 2005). Additionally, when compared to primary psychopaths, secondary psychopaths are reportedly less likely to exhibit the affective deficits seen in primary psychopaths, such as remorselessness, shallow emotional experiences, and lack of empathy (Poythress & Skeem, 2006).

Prior Taxonomic Research

Cluster analytic techniques are statistical methods designed to assign individuals to groups in order to maximize within-group homogeneity and/or between-group differences. Several cluster-analytic studies have uncovered subgroups of offenders consistent with theoretical conceptualizations of primary and secondary psychopaths. A number of these have been based on self-report measures, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI; Blackburn, 1975; Henderson, 1982) the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory (MCMI; Wales, 1995), and the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Hicks, Markon, Patrick, Krueger, & Newman, 2004). These studies corroborate clinical observations regarding heterogeneity within psychopathy. Although self-report measures of psychopathy may be constrained by psychopaths’ proneness to impression management (Book, Holden, Starzyk, Wasylkiw, & Edwards, 2006; Hare, 2003) and lack of insight into their own emotions and motivations (Cleckley, 1976), cluster analytic studies incorporating other methods of assessment have yielded evidence for similar patterns of heterogeneity among psychopaths.

In a study of an adult sample of civil psychiatric patients, Skeem et al. (2004) included both factors of the Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL:SV; Hart, Cox, & Hare, 1995) along with other variables. Their taxonomy consisted of three subtypes of patients, including one group with high scores on both PCL:SV dimensions, and one with lower levels of core psychopathic traits but high levels of lifestyle features of psychopathy (i.e., impulsive and antisocial behavior) and high levels of alcohol and drug use. In a county jail sample, Vassileva et al. (2005) incorporated the two-factor PCL-R model, using Factors 1 and 2 as separate variables in the cluster variate, along with measures of trait anxiety, interpersonal features of psychopathy, and substance abuse. Findings were somewhat similar and congruent with previous studies that identified clusters of primary and secondary psychopaths. Moreover, modest external validity for the clusters was demonstrated using indices of criminal activity. Most recently, Skeem et al. (2007) replicated primary and secondary psychopathic subtypes using the PCL-R four-factor model in a sample limited to violent offenders.

Ethnic Differences in Psychopathy

There is growing evidence that ethnicity is an important factor in the assessment of criminal offenders (Schwalbe, Fraser, Day, & Cooley, 2006). However, ethnicity has been neglected in most prior cluster-analytic studies of psychopathy. Importantly, we do not consider ethnicity to be a meaningful correlate of criminality in and of itself. Instead, we conceptualize it as a marker for demographic contexts in American society (Sampson et al. 2005). Indeed, ethnicity is associated with a variety of different factors, such as neighborhood characteristics (Bickford & Massey, 1991) and differential treatment by the criminal justice system (Tonry, 1995) that might impact criminal classification. In light of substantial ethnic disparities in rates of incarceration and criminal behavior, the consideration of ethnicity is warranted when examining the personality profiles of criminal offenders.

The extent to which psychopathy is manifest in similar ways across ethnicities continues to generate controversy (see Skeem, Edens, Camp, & Colwell, 2004; Sullivan & Kosson, 2006). Prior research suggests that the PCL-R identifies the same latent construct in both African American and European American participants (Cooke, Kosson, & Michie, 2001). Additionally, there is meta-analytic evidence that African Americans and European Americans do not differ on mean total PCL-R scores (Skeem et al. 2004). Although these findings are informative, an equally important empirical issue is whether psychopathy, across ethnicities, reflects the same constellation of features and pattern of relationships within the larger nomological network.

There is some evidence that important correlates of psychopathy differ across ethnicity. Psychopathy scores are associated with different personality traits among European American and African American individuals. Kosson, Smith, and Newman (1990) found that psychopathy was related to extraversion among African Americans but not European Americans. In addition, among European Americans, psychopathy was positively associated with psychoticism, impulsiveness, and monotony avoidance, whereas these relationships were not found among African Americans. Similarly, in European Americans, Thornquist and Zuckerman (1995) and Jackson, Neumann, & Vitacco (2007) have found relationships between psychopathy and impulsivity that did not replicate among African Americans. These data are consistent with the finding that correlations between lifestyle dimension scores and various criteria may differ according to ethnicity (Sullivan, Abramowitz, Lopez, & Kosson, 2006). There is also evidence that relationships between criminality, psychopathy, and other individual level predictors of criminality may differ across ethnic groups. Specifically, Walsh and Kosson (2007) found that individual socioeconomic status moderates the relationship between psychopathy and violent criminality in European Americans but not in African Americans. Such a finding has implications for subtyping in that it suggests that groups of offenders with psychopathic traits may differ across ethnicity with regard to criminal justice outcomes.

Ethnic differences may also extend to the relationships between psychopathy and performance on laboratory tasks. Passive avoidance learning deficits, for example, are well documented among European American psychopaths (Hiatt & Newman, 2006). However, these deficits do not consistently generalize to African Americans (Newman & Schmitt, 1998; Thornquist & Zuckerman, 1995). Taken together, findings regarding psychopathy and ethnicity suggest that it may not be appropriate to generalize relationships between psychopathy and external criteria from European Americans to members of other ethnic groups.

When considering the findings of taxonomic studies of offenders that incorporate the PCL-R, it is important to consider the possibility that ethnic differences may contribute to some of the traits that appear to differentiate subgroups of offenders. However, most prior offender classification studies (e.g., Vassileva et al. 2005) have included all participants, regardless of ethnicity, in the same analysis. In an exception to this trend, a recent study, limited to violent offenders with PCL-R scores of 29 and above, used model-based cluster analysis and found primary and secondary psychopath subtypes in a sample of virtually all Caucasian Swedes (Skeem, Johansson, Andershed, Kerr, & Louden, 2007). Similarly, Swogger and Kosson (2007) used the three-factor PCL-R model, along with measures of anxiety and substance use disorders, and an observational measure of psychopathy, to derive subgroups in a sample of European American inmates with a wide range of total PCL-R scores. Primary and secondary psychopath groups were replicated as part of a four-cluster solution that also included a subgroup of criminals with low levels of psychopathology and a subgroup characterized primarily by moderate anxiety. The profiles replicated across different clustering methods, and external validity for these groups was established using indices of criminal behavior.

The Present Study

The present study was an attempt to replicate the primary and secondary psychopathic subtypes in a sample limited to African American offenders. To facilitate comparison, we ensured that there were few methodological differences between the current study and Swogger and Kosson (2007). Thus, we employed the same exclusion criteria and the same classification variables, and used the most reliable of the methods used in Swogger and Kosson (2007). Where possible, we relied on validated interviews and behavioral assessment measures, instead of self-report measures. To this end, we employed measures of the PCL-R subdimensions and the Interpersonal Measure of Psychopathy (IM-P; Kosson, Steuerwald, Forth, & Kirkhart, 1997) as separate variables in a cluster analysis. Use of the IM-P in addition to the PCL-R has been found to lead to improved prediction of several theoretically important criteria, including adult fighting, interviewer ratings of interpersonal behavior (Kosson et al. 1997), and social cognitive biases (Kosson, Suchy, & Cools, 2001). Moreover, the enhanced assessment of interpersonal behavior associated with psychopathy may help to differentiate among offenders with psychopathic traits. Following Swogger and Kosson (2007), the current study excluded the subcomponent of psychopathy that most directly taps antisocial behavior, in order to provide a more conservative test of external validation via frequency, type, and versatility of criminal behavior.

Similar to other studies (Swogger & Kosson, 2007; Vassileva et al. 2005) we included measures of drug and alcohol abuse/dependence in the cluster variate. Substance abuse may be an important characteristic for the classification of criminal offenders (Cloninger, 1987; Lewis, Rice, & Helzer, 1983; Skeem et al. 2004), and may interact with other personality characteristics to predict criminal behavior. The high prevalence of substance-related disorders among criminal offenders, and the likelihood of observing a cluster of offenders characterized primarily by drug and/or alcohol problems compelled us to include substance abuse/dependence measures in the cluster variate.

Hypotheses

Based on prior research, we hypothesized that the taxonomy would include a group of primary psychopaths. We expected primary psychopaths to be characterized by elevated scores on the interpersonal and affective factors of the PCL-R, and by anxiety scores lower than those of secondary psychopaths (Swogger & Kosson, 2007; Vassileva et al. 2005). Primary psychopaths were also expected to exhibit more violent and nonviolent criminality than nonpsychopathic groups, as well as greater criminal versatility. Moreover, we hypothesized that primary psychopaths would be characterized by more violent charges than secondary psychopaths. We also hypothesized that analyses would identify a group of secondary psychopaths characterized by elevated trait anxiety and elevated scores on the lifestyle dimension of psychopathy. We further hypothesized that secondary psychopaths would be characterized by lower scores on the affective dimension relative to primary psychopaths, as in Swogger and Kosson (2007). Prior studies have identified a secondary psychopath cluster with higher scores on measures of drug and alcohol use problems than members of other clusters (Skeem et al. 2004; Vassileva et al. 2005); therefore we predicted that secondary psychopaths would have higher levels of drug and alcohol use problems than primary psychopaths. We also expected secondary psychopaths to have more criminal versatility than nonpsychopathic groups. Because findings have been mixed, we advanced no hypotheses regarding psychopathy subtypes and nonviolent charges.

Prior subtyping studies have also identified an offender subgroup lacking psychopathic features (Swogger & Kosson, 2007; Vassileva et al. 2005; Wales, 1995). Thus, we predicted a third cluster, consisting of individuals with lower scores on most measures of psychopathology. Although previous studies (Swogger & Kosson, 2007; Vassileva et al. 2005) that used similar cluster variables and data-analytic techniques each uncovered a fourth cluster of offenders, the fourth cluster was dissimilar across studies. Thus, we advanced no hypotheses regarding the characteristics or existence of additional clusters.

Method

Participants

Participants were 262 African American male county jail inmates selected using the following criteria: (1) age between 18 and 44, (2) convicted of a felony or misdemeanor, and (3) data were available on measures used for cluster derivation. Inmates who exhibited overt psychotic symptoms, were unable to read English, or used psychotropic medication at the time of interviewer contact were excluded.

Procedures

Participants were recruited via a telephone within the jail following their identification on an alphabetical list of all inmates. They were paid $5.00 or $8.00 for their involvement in the study, depending on the time period in which they were assessed. Of those invited, approximately 70% agreed to participate. The PCL-R was completed based on a review of institutional files and a semi-structured interview that queried education, relationships, family life, and criminal, medical and work history. Participants also completed a structured clinical interview to assess alcohol and drug abuse and dependence and several self-report measures. Following the assessment, the interviewer completed the IM-P.

Measures Used for Cluster Derivation

Psychopathy Factor Scores

Psychopathy was assessed using the 20-item PCL-R. Extensive research attests to the reliability and validity of the PCL-R (Hare, 2003). Of the structural models proposed to underlie PCL-R scores, a two-factor model (Harpur, Hakstian, & Hare, 1988) has dominated the literature. More recently, however, a three-factor model has been proposed in which Arrogant and Deceitful Interpersonal Style, Deficient Affective Experience, and Impulsive and Irresponsible Lifestyle comprise the factors underpinning psychopathy (Cooke & Michie, 2001). The three-factor model allows for a fine-grained examination of components of the disorder and corresponds closely with the three domains—affective, interpersonal, and behavioral—emphasized in Cleckley’s (1976) descriptive accounts of psychopathy. Additionally, use of the three-factor model minimizes predictor-criterion contamination because it does not include items that relate directly to antisocial behavior. In the present study, factor scores for the three PCL-R dimensions were treated as separate variables in cluster derivation. Observer PCL-R scores were available for 37 (14%) participants in the current sample. Interrater reliability was adequate for PCL-R total scores, average intraclass correlation (ICC) = .95, and for all factor scores (Interpersonal Factor ICC= .84, Affective Factor ICC = .82, Lifestyle Factor ICC =.88).

Interpersonal Features of Psychopathy

The Interpersonal Measure of Psychopathy (IM-P) uses observations of participant behavior during interpersonal interactions to assess core interpersonal features of psychopathy. The IM-P has demonstrated high internal consistency and adequate validity, correlating more highly with Factor 1 than with Factor 2 scores in the two-factor PCL-R model (Kosson et al. 1997; Kosson, Gacono, & Bodholdt, 2000). In the current sample, interrater reliability for the IM-P was adequate, mean ICC = .88 (n = 37) for two independent raters.

Trait Anxiety

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Trait Scale (STAI-T, Form Y; Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983) is a self-report scale widely used to assess a stable propensity to anxiety and negative affect. Scale scores exhibit good internal consistency and convergent validity with scores on other anxiety scales (Spielberger et al. 1983) and anxiety disorder diagnosis (Fisher & Durham, 1999).

Alcohol and Drug Abuse/Dependence

The substance use disorders module of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1997) was used to assess lifetime alcohol and substance abuse/dependence. Separate ordinal variables were generated for severity of alcohol and drug problems ranging from 0 (no abuse), to 1 (abuse) to 4 (severe dependence). Diagnoses based on this module exhibit good interrater reliability (Martin, Pollock, Bukstein, & Lynch, 2000) and validity (Kranzler, Kadden, Babor, & Tennen, 1996).

Measures used for External Validation and Profiling

Demographic Variables

Additional variables assessed for descriptive purposes included: (1) age, and (2) socioeconomic status (SES), as rated using the Hollingshead measure (Hollingshead & Redlich, 1958), which incorporates weighted scores on occupational and educational achievement and yields an index of overall SES that correlates well with several other measures of SES (Deonandan, Campbell, Ostbye, Tummon, & Robertson, 2000).

Criminal Behavior

Data regarding criminal behavior were available for most participants (n = 245). The number of violent and non-violent charges and criminal versatility (i.e., the number of different types of offenses committed) were rated based on interview and file information. Charges were recorded if reported by the participant or noted in the file.

Results

Data Screening

Prior to analysis, cluster variables were screened for multicollinearity and outliers. Variance inflation factors were less than 10 and tolerances were above.10, indicating that no variables were redundant. Screening for outliers revealed four scores greater than three standard deviations from the mean on the IM-P and one extreme score on the STAI-T. Extreme scores were deleted to improve the accuracy of the cluster solution (Comrey, 1985; Hair et al. 1995). All cluster variables were converted to z-scores prior to analysis, as recommended by Hair et al. (1995).

Number of Clusters

Using SPSS 13.0 (SPSS, Inc., 2004), Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative method was used to determine the number of clusters in the dataset as recommended by a number of authors (e.g., Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984; Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1995). The optimal cluster solution was determined by examining percentage changes in agglomeration coefficients for solutions of 2–10 clusters. As shown in Table 1, an examination of agglomeration coefficients revealed increases that remained below .50% at each stage until that in which six clusters were combined to form five. At this stage, an increase in the agglomeration coefficient of 3.76% indicated a large jump in within-cluster variability, suggesting that dissimilar clusters were being combined, and suggesting a six-cluster solution.

Table 1.

Agglomeration coefficients and percentage changes.

| Number of Clusters | Agglomeration Coefficient | Percentage Change to Next Level |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 849.87 | 4.20 |

| 9 | 885.56 | 4.57 |

| 8 | 926.06 | 4.64 |

| 7 | 969.01 | 4.86 |

| 6 | 1016.12 | 8.62 |

| 5 | 1103.66 | 9.50 |

| 4 | 1208.35 | 12.84 |

| 3 | 1363.45 | 14.06 |

| 2 | 1555.14 | 17.48 |

| 1 | 1827.00 | - |

We used the Bootstrap Validation procedure available in ClustanGraphics to verify the reliability of the six-cluster solution, (Clustan Ltd., 1998). Bootstrap validation was conducted using 200 random trials, and evaluation of results was limited to the final 10 fusion points, as in the above examination of agglomeration coefficients. This analysis indicated that coefficients at the six-cluster level exhibited the greatest departure from randomness, suggesting the reliability of the initial agglomeration coefficient analysis.

Developing Cluster Profiles

Whereas Ward’s hierarchical clustering method is useful for determining the number of clusters in a dataset, this method is susceptible to high levels of influence by the cases initially assigned to clusters (Hair et al. 1995). Although the use of k-means clustering procedures seeded with Ward’s centroids can address this problem, the k-means procedures available in major statistical packages may find solutions that are only locally optimal and do not replicate (Steinley, 2006). For this reason, we developed cluster profiles using functions developed by Steinley (2003) that incorporate multiple random seed points rather than seeding with Ward’s method, (MATLAB; MathWorks, 1999; Steinley 2003). There is evidence that these routines are superior to the cluster analytic procedures provided by major statistical packages (Steinley, 2003). To further enhance the reliability we repeated the procedure 1,000 times.

Cluster Profiles

Table 2 presents z-scores for each of the eight variables used to derive the clusters for participants assigned to each of the six clusters. The three replicated clusters, named according to their average characteristics, are summarized below according to general patterns of scores. The three novel clusters are also described.1 As predicted, two of the clusters resembled the primary psychopath and secondary psychopath clusters obtained in previous studies and are described by the same names here.

Table 2.

Cluster profiles (z-scores).

| PP (N=33) | SP (N=42) | LPC (N=48) | AAC (N=35) | ADC (N=49) | DDC (N=55) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anx | −.48 | .47 | −.79 | 1.08 | .49 | .09 |

| Alc | −.31 | .94 | −.64 | −.79 | 1.29 | .27 |

| Drg | −.50 | 1.12 | −.70 | −.28 | −.23 | .95 |

| IMP | 1.17 | .74 | −.46 | −.37 | −.66 | −.65 |

| INT | 1.06 | .91 | −.50 | −.15 | −.69 | −.79 |

| AFF | .56 | .69 | −.40 | .36 | −.08 | −.97 |

| LFST | .19 | .91 | −.80 | .23 | .05 | −.10 |

Note. Anx = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory scores. Alc = Severity of alcohol abuse and dependence. Drg = Severity of drug abuse and dependence. INT = PCL-R Interpersonal Factor scores. AFF = PCL-R Affective Factor scores. LFST = PCL-R Lifestyle Factor scores. IM-P = Interpersonal Measure of Psychopathy. LPC = Low Psychopathology Criminals. PP = Primary Psychopaths. SP = Secondary Psychopaths. AAC = Anxious, Antisocial Criminals. ADC = Alcohol Dependent Criminals. DDC = Drug Dependent Criminals.

No between-cluster differences were found regarding SES. Men in the clusters 1 and 2 (primary and secondary psychopath groups) were significantly older (p < .05) than members of cluster 6 (mean age=23.96). No other age differences were found.

Cluster 1: Primary Psychopaths

This group comprised 12.6% (n = 33) of the sample. These individuals had moderately low anxiety scores, and were characterized by high scores on the interpersonal and affective dimensions of the PCL-R. Their scores on the PCL-R lifestyle factor were slightly elevated. Notably, IM-P scores for members of this group were considerably higher than for men in all other clusters. Primary psychopaths exhibited some alcohol and drug abuse, though their scores were lower than those of members of cluster 2.

Cluster 2: Secondary Psychopaths

This group comprised 16.0% (n =42) of the sample. These individuals had high scores on the IM-P and across all dimensions of the PCL-R. Moreover, they were characterized by moderately high trait anxiety scores and drug and alcohol dependence.

Cluster 3: Low Psychopathology Criminals

This group comprised 18.3% (n =48) of the sample. Individuals in this cluster were characterized by very low anxiety scores and no elevations on the PCL-R factors or on the IM-P. Members of this cluster were characterized by drug abuse and, to a lesser extent, alcohol abuse.

Additional Clusters

Three additional clusters were identified. We advanced no hypotheses regarding these clusters, and they should be considered preliminary until replicated. Members of Cluster 4 (anxious, antisocial criminals; n=35) were characterized by very high anxiety and moderately elevated scores on the PCL-R affective and lifestyle dimensions. Cluster 5 members (alcohol dependent criminals; n=55) were characterized by high anxiety, and alcohol dependence, but moderate to low scores across the PCL-R dimensions. Finally, individuals in Cluster 6 (drug dependent criminals; n=49) exhibited moderate anxiety, low scores across all psychopathy dimensions, and drug dependence.

External Validation and Profiling

Criminal Behavior

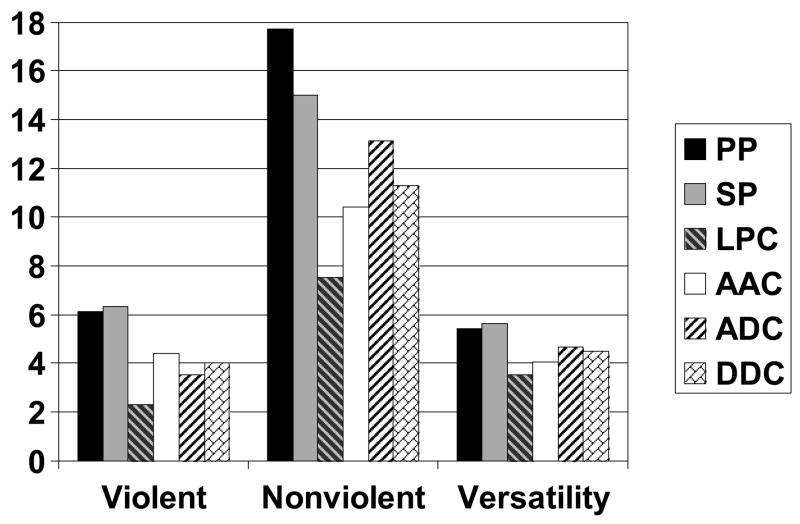

Cluster means for criminal indices are depicted in figure 1. Between-cluster differences were found on number of violent charges, F (5, 239) = 3.55, p < .01, number of nonviolent charges, F (5, 239) = 4.91, p < .01, and criminal versatility, F (5, 239) = 6.67, p < .01. Post hoc tests revealed that primary (Cluster 1) and secondary psychopaths (Cluster 2) had a greater number of violent charges than low psychopathology criminals (Cluster 3) (ds = .75 and .84, ps < .01). Primary and secondary psychopaths also had a greater number of nonviolent charges than low psychopathology criminals (ds = .89 and .78, ps < .01), and primary psychopaths had a greater number of nonviolent charges than anxious, antisocial criminals (Cluster 4); d = .55, p < .05). Finally, both primary and secondary psychopaths displayed greater criminal versatility than low psychopathology criminals (ds = 1.00 and 1.19, ps < .01) and anxious, antisocial criminals (ds = .66 and .80, ps < .05 and < .01).

Figure 1.

Mean violent charges, nonviolent charges, and criminal versatility scores for each cluster.

Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and conduct disorder (CD) symptoms

Clusters differed with regard to ASPD and CD symptoms, F (5, 205) = 25.22, p < .01. Between-cluster comparisons revealed that primary psychopaths displayed more symptoms of ASPD than low psychopathology criminals and members of drug dependent criminals (Cluster 6; ds = 2.20 and .50, ps < .01 and < .05), and more conduct disorder symptoms than low psychopathology criminals (d = 1.65, p < .01). Secondary psychopaths exhibited more symptoms of ASPD (d = .81 to 2.99, p < .01) and conduct disorder (d = .65 to 1.78, ps < .01), than all other clusters except primary psychopaths. Members of Clusters 4, 5, and 6 all had significantly more symptoms of ASPD than low psychopathology criminals (d = 1.43 to 1.89, ps < .01), and members of Cluster 4 and 5 also had more conduct disorder symptoms than low psychopathology criminals (d = 1.21 and .71, ps < .01).

Supplementary Analysis

Because the 7 PCL-R items not included in the three-factor model were excluded from cluster analyses, mean total PCL-R scores including all PCL-R items were calculated for each cluster. These PCL-R total scores are not independent of the PCL-R factor scores that were used in the clustering analyses. Thus, this analysis is not presented as evidence for the validity of the clusters. Nevertheless, PCL total mean scores may be of interest given the large empirical literature addressing correlates of psychopathy. Secondary psychopaths had mean total PCL-R scores above the cutoff of 30 commonly used for the classification of psychopathy (Hare, 2003), M = 31.47, SD = 4.56, and the mean PCL-R scores of primary psychopaths approached this mark, M = 29.64, SD = 3.22. The mean total PCL-R scores for the nonpsychopathic clusters ranged from 15.07 to 25.41.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that distinctive subgroups of inmates with psychopathic features similar to those obtained in prior studies of ethnically diverse and European American samples can be identified among African Americans. Notably, the primary psychopath group was characterized by high levels of the interpersonal and affective traits of psychopathy and by relatively lower levels of anxiety. As such, this group resembles the primary psychopath groups identified in prior studies of criminal subtypes (e.g., Hicks et al. 2004; Skeem et al. 2004; Swogger & Kosson, 2007; Vassileva et al. 2005). Modest external validity for the primary psychopath group was established by comparisons suggesting greater violent and nonviolent criminal behavior and greater criminal versatility than for members of some nonpsychopathic clusters. The finding of a primary psychopath subgroup in a sample limited to African American offenders is novel, and contributes to a growing body of evidence that PCL-R-assessed psychopathy is valid across ethnicity. Furthermore, it extends previous findings of similarity across ethnic groups by replicating a narrowly defined subgroup among African American jail inmates. It is also notable that the primary psychopath group in the present study constituted a similar percentage of the sample (12.6%) as primary psychopath groups in previous taxonomic studies of European American (15.5%; Swogger & Kosson, 2007) and mixed samples (17.0%; Vassileva et al. 2005).

The present study also identified a secondary psychopathic group. This group was similar to secondary psychopaths identified in other studies by virtue of their high scores on the PCL-R lifestyle factor and high anxiety levels, and high levels of drug and alcohol abuse relative to primary psychopaths. These individuals also exhibited relatively high numbers of violent and nonviolent charges and criminal versatility. However, the secondary psychopaths in our sample also exhibited important differences from secondary psychopaths identified in studies in which analyses were not limited to African Americans (e.g., Swogger & Kosson, 2007; Vassileva et al. 2005). Contrary to our prediction, members of our secondary psychopath cluster did not have lower scores than primary psychopaths on the affective dimension of the PCL-R, suggesting similar levels of callousness and emotional shallowness in the two groups. Moreover, whereas in prior studies secondary psychopaths had fewer violent charges than primary psychopaths, present findings indicate a similar number of violent charges for the two groups.

As hypothesized, we also identified a cluster of criminals characterized by low scores on most measures of psychopathology (i.e., low psychopathology criminals). The identification of a low-psychopathology cluster is also consistent with findings from other samples (Swogger & Kosson, 2007; Vassileva et al. 2005).

Our predictions were limited to the three clusters described above; primary psychopaths, secondary psychopaths and low psychopathology criminals. However, our analyses also produced three additional clusters, each with higher mean numbers of ASPD symptoms than low psychopathology criminals. Anxious, antisocial criminals were characterized by considerable anxiety, moderately elevated affective features of psychopathy, and moderately elevated PCL-R lifestyle factor scores, suggesting impulsivity; a trait that is often considered an important feature of secondary psychopaths (Poythress & Skeem, 2006). Interestingly, although members of this cluster were characterized by relatively high scores on the lifestyle dimension, they were not characterized by the higher levels of criminal behavior that are generally associated with elevations on this subcomponent of psychopathy.

Alcohol dependent criminals consisted of nonpsychopathic individuals with elevated anxiety. Given the high rate of alcohol involvement in crime (U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1998), it is conceivable that individuals in this group suffer from alcohol use disorders that lead to difficulties with poor impulse-control and judgement and increase their risk of incarceration. Future studies should include more precise measures of various forms of psychopathology in order to provide a more detailed profile of factors related to high levels of negative affect among these individuals. Finally, drug dependent criminals consisted of nonpsychopathic offenders with serious drug problems.

The finding of six clusters is inconsistent with findings from European American inmates (Swogger & Kosson, 2007) and suggests a more complex taxonomic picture among African Americans. Additionally, in the present sample, external validity analyses using criminal indices yielded fewer distinctions between psychopathic and nonpsychopathic clusters than prior studies that combined ethnic groups (Vassileva et al. 2005) or examined European Americans alone (Swogger & Kosson, 2007). A reason for the weaker link between psychopathy and criminal behavior in the present sample than in prior samples may be that exposure to a wide range of criminogenic factors differs across ethnicity. Candidates for such factors include both individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status (Walsh & Kosson, 2007), as well as more narrow band constructs such as concentrated poverty (Silver et al. 1999; Lynam et al. 2000) and social cohesion (Cutrona et al. 2005; Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). Our findings argue for the importance of future studies to explicitly examine ethnic difference in exposure to and consequences of these sociodemographic factors to clarify these potentially important relationships.2

Two limitations of the present study are notable. First, the use of alternative criteria for determining the cluster solution might have resulted in the identification of a different number of groups of offenders. However, converging evidence from the analysis of agglomeration coefficients and the bootstrapping analysis suggested that the six-cluster solution identified in the present study was appropriate. Second, as is the case with all cluster analyses, the use of different variables in the analysis, or a different PCL-R factor model, might have resulted in a different cluster solution. Indeed, the similarity of several of the clusters suggests that additional cluster variables might have resulted in a more complete picture of offender psychopathology. Studies including other individual differences variables are needed to evaluate the replicability of the novel clusters obtained in this study and to examine whether the members of these clusters differ on additional dimensions that were not assessed in this study.

Present findings provide evidence for the replicability of a primary psychopath cluster in a sample of African American jail inmates. The finding that a subgroup of criminals who resemble the classical conceptualizations of the psychopath (e.g. Cleckley, etc.) can be identified in a culturally distinct sample speaks well for the stability and robustness of the psychopathy construct. However, given the nature of present findings (i.e., a more complex cluster solution and more limited external validation) relative to those in studies not limited to African Americans, the current study also highlights the importance of caution in generalizing offender taxonomies across ethnicity. Indeed, our findings provide further evidence that the characteristics of individuals who face incarceration in the US are not equivalent across ethnicity. Given dramatic ethnic disparities in rates of arrest and incarceration in the US (Tonry, 1997), the differences between our findings and those of previous studies may reflect the broader net cast by the criminal justice system for members of the African American population. Future offender subtyping studies that incorporate separate analyses by ethnicity will help to further our understanding of ethnicity as a moderator of the predictive utility of offender taxonomies, and provide data regarding the reliability of current results. Additionally, future investigations of important external correlates may further clarify the nature of the criminal subgroups.

Acknowledgments

The research and preparation of this article were supported in part by Grants MH49111 and MH57714 from the National Institute of Mental Health to David S. Kosson. The study was approved by the IRB. Thanks to Patrick Firman and the staff of Lake County Jail in Waukegan, Illinois for their consistent cooperation and support during the conduct of this research. Thanks to John Woodard for assistance in using MATLAB, and also to Sharon Flicker, Ann Russ, Peter Britton and Tom O’Conner for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Although significance tests for variables in the cluster variate are sometimes presented as part of cluster descriptions, such tests are not relevant to cluster validation. By definition, cluster analysis is designed to maximize differences between groups of individuals on clustering variables. In addition, observations are not assigned to groups randomly, violating the assumptions of statistical significance tests (Steinley, personal communication, July 25, 2007).

Although it is also possible that the smaller number of differences across clusters reflects the reduced statistical power associated with dividing a similarly sized sample of participants into six instead of four clusters, a comparison of effect sizes suggests that the mean differences between men in the primary psychopath and two of the nonpsychopathic clusters were smaller than those reported by Swogger and Kosson (2007).

Contributor Information

Marc T. Swogger, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY

Zach Walsh, Department of Psychiatry, Brown University Medical School, Providence, RI.

David S. Kosson, Department of Psychology, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, IL

References

- Aldenderfer M, Blashfield R. Cluster Analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bickford A, Massey D. Segregation in the second ghetto: Racial and ethnic segregation in American public housing, 1977. Social Forces. 1991;69:1011–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn R. An empirical classification of psychopathic personality. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1975;127:456–460. doi: 10.1192/bjp.127.5.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJR. The emergence of psychopathy: Implications for a neuropsychological approach to developmental disorders. Cognition. 2006;101:414–442. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Book AS, Holden RR, Starzyk KB, Wasylkiw L, Edwards MJ. Psychopathic traits and experimentally induced deception in self-report assessment. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;41:601–608. [Google Scholar]

- Borgan FH, Barnett DC. Applying cluster analysis in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1987;34:456–468. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley CA, Newman JP, Widiger TA, Lynam DR. Two approaches to parsing the heterogeneity of psychopathy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11:69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Alcohol and Crime: An analysis of national data on the prevalence of alcohol involvement in crime. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice; 1998. Retrieved February 9, 2008, from the World Wide Web. http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/ac.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Calamari JE, Wiegartz PS, Riemann BC, Cohen RJ, Greer A, Jacobi DM, Jahn SC, Carmin C. Obsessive-compulsive disorder subtypes: An attempted replication and extension of a symptom-based taxonomy. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2004;42:647–670. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleckley H. The Mask of Sanity. 5. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements CB. Offender classification: Two decades of progress. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1996;23:121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science. 1987;236:410–416. doi: 10.1126/science.2882604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clustan, Ltd. Bootstrap Validation. 1998 Retrieved February 15th, 2005. Available: http://www.clustan.com/bootstrap.html.

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comrey AL. A method for removing outliers to improve factor analytic results. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1985;20:273–281. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2003_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke DJ, Kosson DS, Michie C. Psychopathy and ethnicity: Structural, item, and test generalizability of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R) in Caucasian and African American participants. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:531–542. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.13.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke DJ, Michie C. Refining the construct of psychopathy: Towards a hierarchical model. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:171–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russel DW, Brown PA, Clark LA, Hessling RM, Gardner KA. Neighborhood context, personality, and stressful life events as predictors of depression among African American women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:3–15. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas KS, Vincent GM, Edens JF. Risk for Criminal Recidivism: The role of psychopathy. In: Patrick CJ, editor. Handbook of Psychopathy. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBL. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-IV Disorders (SCID-I), Clinician Version. New York: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PL, Durham RC. Recovery rates in generalized anxiety disorder following psychological therapy: An analysis of clinically significant change in STAI-T across outcome studies since 1990. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:1425–1434. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpur TJ, Hakstian AR, Hare RD. Factor structure of the psychopathy checklist. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:741–747. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.5.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WL. Multivariate data analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hale LR, Goldstein D, Abramowitz CS, Calamari JE, Kosson DS. Psychopathy is related to negative affectivity but not to anxiety sensitivity. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:697–710. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00192-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. Psychopathy, affect, and behavior. In: Cooke DJ, Forth AE, Hare RD, editors. Psychopathy: Theory, research, and implications for society. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishing; 1998. pp. 105–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. Hare psychopathy checklist-revised (PCL-R) 2. Toronto, ON, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harpur TJ, Hare RD. Psychopathy and violent behavior: Two factors are better than one; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association; San Francisco, CA. 1991. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Hart SD, Cox DN, Hare RD. Manual for the Hare Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL-SV) Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson M. An empirical classification of convicted violent offenders. British Journal of Criminology. 1982;22:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt KD, Newman JP. Understanding psychopathy: The cognitive side. In: Patrick CJ, editor. Handbook of Psychopathy. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 334–352. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Krueger RF, Newman JP. Identifying psychopathy subtypes on the basis of personality structure. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:276–288. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC. Social Class and Mental Illness. New York: Wiley; 1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RL, Neumann CS, Vitacco MJ. Impulsivity, anger, and psychopathy: The moderating effect of ethnicity. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:289–304. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosson DS, Gacono CB, Bodholdt RH. Assessing psychopathy: Interpersonal aspects and clinical interviewing. In: Gacono CB, editor. The Clinical and Forensic Assessment of Psychopathy. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 203–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kosson DS, Smith SS, Newman JP. Evaluating the construct validity of psychopathy in black and white male inmates: Three preliminary studies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:250–259. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosson DS, Suchy Y, Cools J. Social cognitive biases in psychopathic Adolescents; Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Research in Psychopathy; Madison, WI. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kosson DS, Steuerwald BL, Forth AE, Kirkhart KJ. A new method for assessing the interpersonal behavior of psychopathic individuals: Preliminary validation studies. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Karpman B. On the need for separating psychopathy into two distinct clinical types: symptomatic and idiopathic. Journal of Criminology and Psychopathology. 1948;3:112–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Kadden RM, Babor TF, Tennen H. Validity of the SCID in substance abuse patients. Addiction. 1996;91:859–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leistico AR, Salekin RT, DeCoster J, Rogers R. A large-scale meta-analysis relating the Hare measures of psychopathy to antisocial conduct. Law and Human Behavior. 2008;32:28–45. doi: 10.1007/s10979-007-9096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CE, Rice J, Helzer JE. Diagnostic interactions: Alcoholism and antisocial personality. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1983;171:105–113. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198302000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykken DT. The antisocial personalities. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Caspi A, Moffit TE, Wikstrom P, Loeber R, Novak S. The interaction between impulsivity and neighborhood context on offending: The effects of impulsivity are stronger in poorer neighborhoods. 2000 doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Pollock NK, Bukstein OG, Lynch KG. Inter-rater reliability of the SCID alcohol and substance use disorders section among adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59:173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MathWorks. MATLAB [computer software] Natick, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Newman JP, Schmitt WA. Passive avoidance in psychopathic offenders: A replication and extension. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:527–532. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Hicks BM, Krueger RF, Lang AR. Relations between psychopathy facets and externalizing psychopathology in a criminal offender sample. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:339–356. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.4.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poythress N, Skeem JL. Disaggregating psychopathy: Where and how to look for subtypes. In: Patrick CJ, editor. Handbook of Psychopathy. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 172–192. [Google Scholar]

- Salekin R, Rogers R, Ustad KL, Sewell KW. Psychopathy and recidivism in female inmates. Law and Human Behavior. 1998;22:109–128. doi: 10.1023/a:1025780806538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Raudenbush SW. Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:224–232. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe CS, Fraser MW, Day SH, Cooley V. Classifying juvenile offenders according to risk of recidivism: Predictive validity, race/ethnicity, and gender. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2006;33:305–324. [Google Scholar]

- Silver E, Mulvey EP, Monahan J. Assessing violent risk among discharged Psychiatric patients: Toward an ecological approach. Law and Human Behavior. 1999;23:237–255. doi: 10.1023/a:1022377003150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, Edens JF, Camp J, Colwell LH. Are there ethnic differences in levels of psychopathy? A meta-analysis. Law and Human Behavior. 2004;28:505–527. doi: 10.1023/b:lahu.0000046431.93095.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, Johansson P, Andershed H, Kerr M, Louden JE. Two subtypes of psychopathic violent offenders that parallel primary and secondary variants. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:395–409. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, Mulvey EP, Appelbaum P, Banks S, Grisso T, Silver E, Robbins PC. Identifying subtypes of civil psychiatric patients at high risk for violence. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2004;31:392–437. [Google Scholar]

- Skre I, Onstad S, Torgersen S, Kringlen E. High inter-rater reliability for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I (SCID-I) Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1991;84:167–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb03123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y) Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS, Inc. SPSS 13.0 base user’s guide. Chicago, IL: Prentice Hall; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Steinley D. Local optima in k-means clustering: What you don’t know may hurt you. Psychological Methods. 2003;8:294–304. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinley D. Profiling local optima in k-means clustering: Developing a diagnostic technique. Psychological Methods. 2006;11:178–192. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swogger MT, Kosson DS. Identifying subtypes of criminal psychopaths: A replication and extension. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2007;34:953–970. doi: 10.1177/0093854807300758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EA, Abramowitz C, Lopez M, Kosson DS. Reliability and construct validity of the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised for Latino, European American, and African American male inmates. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18:382–392. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EA, Kosson DS. Ethnic and cultural variations in psychopathy. In: Patrick CJ, editor. The Handbook of Psychopathy. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 437–458. [Google Scholar]

- Thornquist MH, Zuckerman M. Psychopathy, passive avoidance learning, and basic dimensions of personality. Personality and Individual Differences. 1995;19:525–534. [Google Scholar]

- Tonry M. Malign Neglect: Race, crime and punishment in America. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tonry M. Ethnicity, Crime and Immigration: Comparative and Cross-National Perspectives. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Vassileva J, Kosson DS, Abramowitz C, Conrod P. Psychopathy versus psychopathies in classifying criminal offenders. Legal and Criminological Psychology. 2005;10:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wales D. Personality disorder in an outpatient offender population. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 1995;5:85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh Z, Kosson DS. Psychopathy and violent crime: A prospective study of the influence of socio-economic status and ethnicity. Law and Human Behavior. 2007;31:141–157. doi: 10.1007/s10979-006-9057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh Z, Walsh T. The evidentiary introduction of Psychopathy Checklist-Revised assessed psychopathy in U.S. courts: Extent and appropriateness. Law and Human Behavior. 2006;30:493–507. doi: 10.1007/s10979-006-9042-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolondek S, Lilienfeld SO, Patrick CJ, Fowler KA. The interpersonal measure of psychopathy: Construct and incremental validity in male prisoners. Assessment. 2006;13:470–482. doi: 10.1177/1073191106289861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]