Abstract

Emerging molecular and clinical data suggest that ETS fusion prostate cancer represents a distinct molecular subclass, driven most commonly by a hormonally regulated promoter and characterized by an aggressive natural history. The study of the genomic landscape of prostate cancer in the light of ETS fusion events is required to understand the foundation of this molecularly and clinically distinct subtype. We performed genome-wide profiling of 49 primary prostate cancers and identified 20 recurrent chromosomal copy number aberrations, mainly occurring as genomic losses. Co-occurring events included losses at 19q13.32 and 1p22.1. We discovered 3 genomic events associated with ERG rearranged prostate cancer, affecting 6q, 7q, and 16q. 6q loss in non- rearranged prostate cancer is accompanied by gene expression deregulation in an independent dataset and by protein deregulation of MYO6. To analyze copy number alterations within the ETS genes, we performed a comprehensive analysis of all 27 ETS genes and of the 3Mbp genomic area between ERG and TMPRSS2 (21q) with an unprecedented resolution (30 bp). We demonstrate that high-resolution tiling arrays can be used to pin-point breakpoints leading to fusion events. This study provides further support to defining a distinct molecular subtype of prostate cancer based on the presence of ETS gene rearrangements.

Keywords: ETS genes, prostate cancer, gain, loss

INTRODUCTION

Recent discoveries in the field of prostate cancer have dramatically altered the understanding of the basic molecular mechanisms that underlie the progression of this heterogeneous disease. It is now well-established that the majority of prostate cancers harbor gene fusions involving the ETS family of transcription factors. The ETS gene family represents a highly conserved group of genes that were originally identified with the discovery of the v-ETS oncogene from the avian leukemia virus, E26, ERG (Leprince et al., 1983). The ETS family of transcription factors consists of 27 genes that share a highly conserved winged helix-turn-helix DNA binding domain (ETS domain). The biological function of ETS transcription factors is only incompletely understood, however, several of the ETS genes have been implicated in oncogenesis. The ETS transcription factors FLI1 (Friend leukemia virus integration 1), ETV1 (Ets variant gene 1), and ERG have been observed in gene rearrangements in leukemia, sarcoma, and prostate cancer. Following the discovery by Tomlins et al., reporting recurrent fusions of the androgen regulated gene TMPRSS2 (Transmembrane protease, serine 2) and the transcription factors ERG and ETV1 (Tomlins et al., 2005), subsequent studies showed additional fusions involving the ETS genes and various 5′ partners (Tomlins et al., 2006, 2007; Helgeson et al., 2008). In most cases, the ETS gene fusion partners act as upstream promoters driving the ETS gene expression.

Several pieces of evidence suggest that ETS fusion prostate cancers are a subclass of prostate cancer. First, ERG rearranged prostate cancers have a distinct expression signature (Setlur et al., 2008). Second, they have a more aggressive natural history as demonstrated by two independent Watchful Waiting cohorts (Demichelis et al., 2007; Attard et al., 2008), and third they are characterized by a distinct histologic phenotype (Mosquera et al., 2007). However, the alterations at the genomic level (with the exception of deletion of the genomic segment between TMPRSS2 and ERG) that might further characterize this subclass remain largely unexplored. To this end, we performed a genome-wide DNA analysis using Affymetrix 250K SNP arrays to explore the somatic genomic alterations that might further serve to characterize this subclass and provide biologic insights. We designed a high resolution NimbleGen tiling array to look for changes in the 27 ETS genes and to map genomic breakpoints. Collectively, we show strong evidence for specific genomic alterations associated with the ERG rearranged prostate cancer subclass.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Patient Population

Prostate cancer samples and matched benign prostate tissue were taken from 51 men diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer between 2003 and 2004 at the Department of Urology, University of Ulm, (Ulm, Germany), where they underwent radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection with curative intent. The samples were selected from a consecutive series based on adequacy of tumor density available material for SNP analysis. The patient population is comparable to the one earlier described (Hofer et al., 2006). All tumors were staged using the 2002 TNM system (Greenlee et al., 2001) and graded according to the revised Gleason Grading System (Amin et al., 2003). The distribution of the Gleason Grade in this population was the following: 2% had Gleason Grade 5, 25% had Gleason Grade 6, 57% had Gleason Grade 7, 8% had Gleason Grade 8, and 8% had Gleason Grade 9. ERG rearrangement status was successfully evaluated for 50 samples by break-apart FISH test as in (Perner et al., 2006); 38% (n=19) were negative and 62% (n=31) were positive. Of the 31 ERG rearranged samples, 55% (n=17) demonstrated deletion of ERG telomeric probe.

Cell line and Xenografts

The NCI-H660 cell line was obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and was maintained according to the supplier’s instructions. The Xenograft DNA was a kind gift from Dr. Robert Vassella, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Dual-color Interphase FISH Assays

To assess for ERG rearrangement, we performed a break-apart assay. For frozen material, a 5jm section was cut and allowed to thaw at room temperature (~3–5 minutes). Slides were then fixed in 4% buffered formalin for 2 minutes and rinsed in 1× PBS. After fixation, slides were pre-treated at 94° C in Tris/EDTA, pH 7.0, buffer for 0.5 hours before protein digestion with Zymed Digest-All (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and ethanol dehydration. Following co-denaturation of the probes and samples (5 minutes at 75° C), slides were immediately placed in a dark moist chamber to hybridize for at least 16 hours at 37° C. After overnight hybridization, washing and color detection was performed as described previously (Perner et al., 2006). Out of 51 frozen tissues, 50 were successfully evaluated.

To confirm the alterations of interest as identified through genome-wide profiling, two color interphase FISH assays were designed for specific loci on 16q, 7q, and 6q and performed on a set of 11 frozen samples (8 positive for ERG rearrangement and 3 negative). For 16q, BAC clones RP11-206B18 and RP11-662L15 were applied, targeting an area located at 16q23.1–23.2 containing the MAF gene. For 7q, BAC clone RP11-204M9 was applied, targeting an area located at 7q22.1 containing the MCM7 gene. For 6q, BAC clone RP11-944L22 was applied, targeting an area located at 6q14.3 containing the SNX14 gene. Reference probes were also used for each chromosome within a stable region identified by SNP array data (see above). For chromosomes 16, 7, and 6, the BAC clones used were RP11-309I14, RP11-91E16, and RP11-943N14, respectively. All target probes were Biotin-14-dCTP labeled (eventually conjugated to produce a red signal) and all reference probes were Digoxigenin-11-dUTP labeled (eventually conjugated to produce a green signal). Correct chromosomal probe localization was confirmed on normal lymphocyte metaphase preparations. All BAC clones were obtained from the BACPAC Resource Center, Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute (CHORI) (Oakland, CA).

The samples were analyzed under a 60x oil immersion objective using an Olympus BX-511 fluorescence microscope, a CCD (charge-coupled device) camera and the CytoVision FISH imaging and capturing software (Applied Imaging, San Jose, CA) Semi-quantitative evaluation of the tests was independently performed by two evaluators (S.P., C.J.L.). For each case, we attempted to analyze at least 100 nuclei.

DNA Isolation

Areas enriched for tumor and benign tissue were identified and circled by the study pathologists (SP, MAR). Two biopsy cores, each 1.5 mm in diameter, were manually punched and placed in individual wells of a 96-well plate on dry ice. The tissue was lysed by incubating for 24–48 hours with lysis buffer (NaCl 100mM, EDTA pH 8.5 25mM, Tris pH 8.0 10mM, SDS 0.5%) containing 1 mg/mL proteinase K (Ambion, Austin, TX). Following this, automated DNA extraction was carried out using the CyBio liquid handling system. The DNA was extracted using equal volume of 25/24/1 phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol. Isopropanol containing 0.7 M sodium perchlorate and 20ug glycogen (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used for precipitation. Following a wash with 70% ethanol, the DNA pellet was resuspended and quantitated using Picogreen assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). 500ng of DNA was used for the 250K SNP array platform (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). DNA from the cell line was extracted using 106–107 cells using the phenol chloroform extraction procedure described above. The xenograft DNA was isolated using DNAzol (Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, OH).

SNP Array Experiments and Data Analysis

Genomic DNA from paired cancer and benign prostate tissue from 51 individuals (N=102) as well as from the NCI-H660 cell line and from the corresponding index case was hybridized to the 250K Sty I chip of the 500K Human Mapping Array set, Affymetrix Inc, which interrogates ~238,000 SNP loci. Arrays were hybridized and scanned using the GeneChip Scanner 3000 at the core facility of the Broad Institute of MIT, Cambridge, MA. Probe level signal intensities were normalized utilizing an invariant set of probes identified for each array against a baseline array (benign tissue sample). Normalized probe level intensities were then modeled using PM-MM difference modeling method (background removal) as in dChip (Li and Hung Wong, 2001) to obtain SNP level intensities. Three quality control steps were applied, based on genotype call rate (threshold was set at 85%), single sample intensity distribution, and assessment of genotype distances for all pair of samples within the dataset. The intensity distribution step evaluates if the tumor and normal samples exhibit the expected signal distribution, where genomic aberrations are expected to be present in tumors and not in normal samples. For a normal diploid sample, the excepted distribution for the log2 intensities is a one mode distribution centered in 1. In fact, when considering the entire genome signal distribution, germline copy number variations are expected to show minor signal variation (i.e., masked by the signal noise). The genotype distance evaluation implemented as in SPIA (Demichelis et al., 2008) ensures that there are no duplicates in the dataset and that the prostate cancer tissue and prostate normal tissue are correct matches. We then smoothed and segmented the log2 intensities using GLAD (Hupe et al., 2004) with d set equal to 10. A total of 49 primary tumor samples passed all quality control steps and were included in final analysis.

To detect potential recurrent changes concordant across the dataset and therefore less likely to be random passenger events, we applied GISTIC (Beroukhim et al., 2007) to our segmented dataset. Briefly, this approach considers frequency and dosage of variation across the genome and ultimately assigns a q-value to each locus, reflecting the possibility that the event is due to fluctuations. The statistical evaluation for significance is separately performed for amplifications and losses. The analysis generates a list of significant recurrent changes, each characterized by change peak boundaries and corresponding q-value (threshold set to 0.25). To meaningfully apply this approach to our data and extract consistent information, we needed to define a threshold on the intensity signal to distinguish between noise fluctuation and biological signal variation. We reasoned that the appropriate way was to use prior knowledge on the well characterized interstitial deletion in chromosome band 21q22 (Perner et al., 2006). We identified the samples annotated as ERG rearrangement positive with deletion of the ERG telomeric probe by FISH test and showing presence of deletion by SNP data. We then selected the one with the lowest absolute value of the log2 intensity ratio and set the threshold to that value. Association between lesions (presence or absence) and between single lesion and phenotype was evaluated by Fisher exact test. All p-values are 2-sided, unless otherwise specified.

Custom ETS Fusion Prostate Cancer Tiling Array Design and Experiments and Breakpoint Identification

Tiling arrays allow for high-resolution mapping of copy number genomic polymorphisms, including small to moderately sized (0.5–10kb) deletions and insertions, across large regions of the human genome using total genomic DNA (Urban et al., 2006). Oligonucleotide arrays with 385,000 features can be synthesized by photolithography; by tiling large segments of genomic DNA, these arrays have the potential to map deletions at very high resolution. In addition, the sensitivity of suitably designed arrays is sufficiently high that total genomic DNA can be directly hybridized, thus avoiding bias that arises during selective PCR amplification of subsets of the DNA.

We designed a custom tiling path NimbleGen array for the study of ETS fusion prostate cancer. We prioritized high resolution coverage for the ETS gene regions (average intermarker distance ~30bp) and for the ~3Mbp area between ERG and TMPRSS2 on chromosome arm 21q (average intermarker distance ~20bp). Regions previously reported to be associated with prostate cancer were also included on the chip at ~2.6Kbp resolution. Two control regions were also included in the design to be used as zero state reference (chr12:99,000,001–102,000,000 and chr19:14500001–20000000 location), at a resolution of ~2Kbp. Four samples were hybridized on the ETS fusion prostate cancer tiling array: 1 blood sample (NA12156), 1 cell line (NCI-H660), 2 xenografts (LuCaP86.2 and LuCaP35), and one tissue sample (LN13, lymphonode). All prostate cancer samples were positive for TMPRSS2-ERG rearrangement (Perner et al., 2006). In addition, LuCap93 was hybridized on tiling array as in Urban et al. (2006). All the experiments were carried out at NimbleGen Systems, Reykjavik, Iceland.

Data Analysis

Fluorescence intensity raw data were obtained from scanned images of the oligonucleotide tiling arrays by using NIMBLESCAN 2.3 extraction software (NimbleGen Systems). For each spot on the array, log2-ratios of the Cy3-labeled test sample versus the Cy5-labeled reference sample were calculated. Due to the highly skewed design towards prostate cancer aberrations, the single sample data were not conventionally normalized, but subtracted by the median value of the log2 intensity ratios of the two control regions. For visualization purposes, tiling array data are smoothed using a pseudo-median approach (Royce et al., 2007). Here we used a sliding window of 100 markers.

Breakpoint Identification

The tiling array data were analyzed for breakpoints using BreakPtr algorithm (Korbel et al., 2007). This is described in the supplemental materials. Vectorette PCR amplification system (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used to identify the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion breakpoint. Briefly, 2μg of DNA were digested using EcoRI/HindIII restriction enzymes and cloned into vectorette units which contain adapter sequences of the corresponding restriction enzymes. The co-ordinates from the analysis were used to design sequence specific primers for PCR. The ligated vecorette libraries were used as templates for PCR reactions with the sequence specific primer (ERGVEC_FWD_PRIMER8: 5′AGAAGCCTCCCAAATCTGTATCTTATGG 3′) and the reverse vectorette primer. The products were sequenced using the sequence specific primer at MWG biotech Inc., Highpoint, NC.

Genomic Location Enrichment Analysis for Transcript Data

To study potential genome location enrichment for ETS fusion related genes, we analyzed two prostate cancer gene expression datasets, annotated for ERG rearrangement. We focused on fusion genes selected through consensus procedure for association with prostate cancer rearrangement status: genes selected more than 5% out of 100 iterations. We applied consensus gene selection procedure as in JCNI (Setlur et al., 2008). Briefly, we repeated 10 splits of 10 fold cross validation of t-test, with p<0.00005 (SW) and p<0.001 (PHS) as thresholds, respectively. The enrichment analysis (using 5% as fusion gene selection threshold) included 233 (SW) and 107 (PHS) genes associated with ERG rearrangement (162 and 71, and 48 and 59 down- regulated and up-regulated genes, respectively). We defined the enrichment score as: ESregion = (NfusionGenesregion/NfusionGenes) (NGenesregion/NGenes). Region can be chromosome or chromosomal arm. ESregion greater than 1 indicates that the region is enriched for rearrangement associated genes. Maximum enrichment score occurs when all genes in the region of interest are all the genes associated with rearrangement (for SW would be 48). We applied p-values by means of Hypergeometric distribution.

Immunohistochemistry for MYO6

Paraffin-embedded tissue microarray section, 4μm thick, was deparaffinated and rehydrated using xylene and graded ethanol respectively. Pressure cooking with citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 minutes was used as antigen retrieval method. Primary antibody Myosin VI, 1:50 dilution (mouse monoclonal, clone MUD-19, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) was stained on the Leica Microsystems Bond-Max Autostainer using DakoCytomation Envision and System Labeled Polymer HRP anti-mouse (K4001). Evaluation of the protein expression was performed by visual inspection (MAR).

RESULTS

Recurrent Aberrations in Primary Prostate Cancer

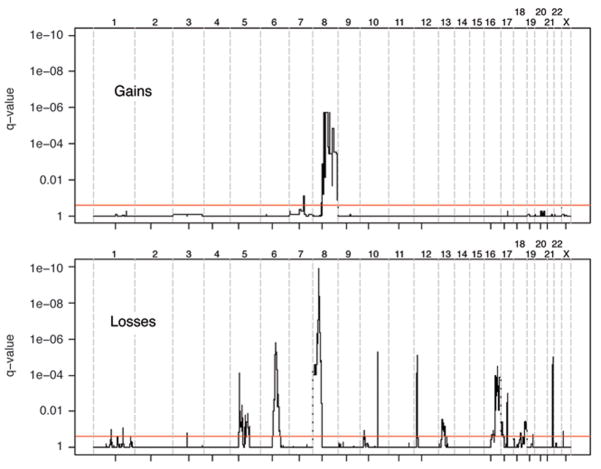

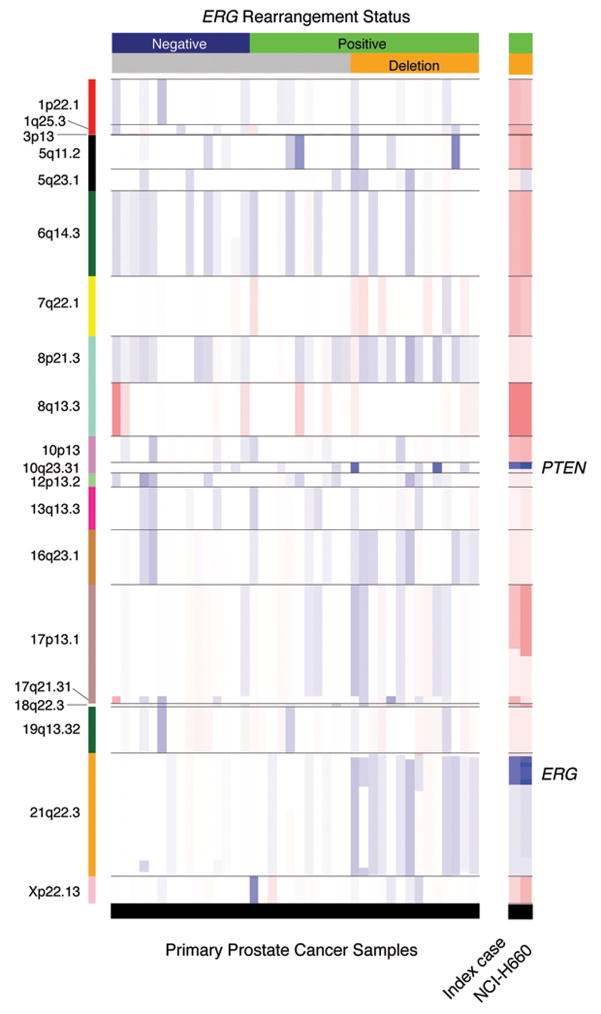

To determine the genomic landscape of primary prostate cancer and identify recurrent copy number alterations, we successfully profiled 49 well-annotated tumors using the high-density genome-wide Affymetrix platform, querying ~238000 loci. To distinguish somatic changes from germline structural variations, we normalized tumor DNA signal to normal prostate DNA signal generated from the same individual. Our analysis detected 20 recurrent events with frequencies ranging from 10% to 43%. Ninety percent of the events (18 out of 20) were losses, with loss at 8p21.3 and 6q14.3 being the most common alterations. A minority of recurrent events (n=2) were gains, located at 8q13.3 and 7q22.1, with low to moderate copy number increases. Nine samples did not show any of these distinct recurrent lesions, and were characterized by only a weak aberrant signal. The genome-wide profile for gains and losses evaluated in our tumor cohort is shown in Figure 1, where the most significant genomic changes are represented by lower q-value. Statistically significant recurrent events are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Interestingly, some events tend to co-occur (see Figure 2). All 19q13.32 losses (N=5) occur in the presence of 1p22.1 loss (Fisher exact test p-value < 0.001). Similarly, losses on 17q21.31 and on 21q22.3 co-occur with losses on 18q22.3 and 16q23.1, respectively (Fisher exact test p-values of 0.004 and 0.001). A comparison between these findings and genomic aberrations previously detected by our group on more advanced tumor samples profiled using 100K Affymetrix Array (Perner et al., 2006) indicates overall agreement and suggests that prostate tumors accumulate gains over time (see Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1. Genomic aberrations in primary prostate cancers as evaluated on a collection of 49 samples.

The red lines identify q-values of 0.25 as cut-off for significance. Q-values are plotted along the genomic location, with chromosomes delineated by vertical dotted lines and centromeres by small marks. The top frame refers to gains (amplification) and the lower frame to losses (deletions).

Figure 2. Smoothed segmented copy number data of recurrent lesions.

The heatmap shows log2 intensity ratios within the detected recurrent lesions (annotated by chromosome band on the left side). The 40 prostate cancer samples harboring the recurrent lesions are presented, ordered based on ERG rearrangement status (upper horizontal bar) and by deletion status of ERG telomeric probe as assessed by dual-color FISH. The right hand profiles show the genomic status of the same regions in NCI-H660 cell line and in the corresponding index case (prostate cancer metastasis). Red and blue colors indicate gains and losses, respectively. Color intensity corresponds to copy number change amplitude. White indicates no change.

Genomic Aberrations Characteristic of ERG Rearranged Prostate Cancer

We recently demonstrated that ERG rearranged prostate cancers are characterized by an 87 gene signature (Setlur et al., 2008), supporting the view that these tumors belong to a distinct subclass. Other than the common interstitial deletion between ERG and TMPRSS2 (21q22 deletion) (Perner et al., 2006), we observed that ERG rearranged and ERG non-rearranged prostate cancer do not differ in terms of overall frequency of copy number alterations, with an average number of lesions being 4.4 +/− 2.7 and 3.5 +/− 2.5, respectively. Of the 20 recurrent events, 3 showed significant association with ERG rearranged genotype: gain on 7q (p-value = 0.04) and deletion on 16q (p-value = 0.04), enriched in rearranged cases and deletion on 6q (p-value = 0.02), enriched in non-rearranged cases. Figure 3a demonstrates the presence or absence of these 3 lesions for the 40 cases which showed recurrent aberrations, sorted with respect to ERG rearrangement status. The combination of losses on 16q and 6q accounts for 75% of ERG rearranged cases. In our series, we did not detect any association between ERG rearrangement and PTEN (Phosphatase and tensin homolog (mutated in multiple advanced cancers 1)) loss. Decreased copy number of PTEN was seen in 16% of the cases (with 2 cases showing loss of both copies), a much lower frequency than recently reported by Yoshimoto et al. (2007).

Figure 3. ERG rearranged prostate cancer lesions.

A, Binary representation of three genomic recurrent lesions associated with ERG rearranged prostate cancer (gray indicates absence, black indicates presence of lesion). The samples are sorted by ERG rearrangement status and annotated for deletion status of ERG telomeric probe as assessed by dual-color FISH. B, Distributions of transcript expression of SNX14, MCM7, and MAF genes in two sets of ERG rearranged negative and ERG rearranged positive prostate cancers as determined by expression profiling. The genes were selected as centrally located in the three fusion associated lesions. C, Monoallelic deletion for SNX14 in primary prostate cancer cell as determined by FISH. A representative tumor nucleus demonstrates the loss of a red probe at 6q14.3.

The genomic profile of the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion positive NCI-H660 cell line (Mertz et al., 2007), derived from a pulmonary metastasis of an aggressive small cell carcinoma of the prostate, shows characteristic deletions of 21q22 and PTEN locus (10q23) and abundant amplifications in the most commonly altered prostate cancer loci (see right hand side of Figure 2). Multicolor FISH (M-FISH) was performed on the NCI-H660 cell line revealing a complex karyotype presumably due to a high degree of genomic instability. In addition, 50% of the cells analyzed were hyperdiploid and the rest were polyploid (consistent with whole chromosome gains observed in the SNP data), with the exception of chromosomes 21 and X. Chromosome Y was seen to be lost (Supplemental Figure 2).

In situ Validation

In order to validate the recurrent lesions associated with the rearranged cancer subclass, we chose genes within the area of maximum statistical confidence and prioritized genes that were demonstrated to be functionally important in cancer progression. For the in situ validation, we performed FISH test to assess for copy number alterations of SNX14 (sorting nexin 14) (Figure 3c), MCM7 (Minichromosome maintenance complex component 7), and MAF (v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog (avian)) located in the peak lesions of 6q, 7q, and 16q on a selection of samples (N=11). We were able to confirm all three aberrations (the concordances between SNP data and FISH were 82%, 73%, and 73%) (data not shown). In few cases we observed mosaicism (presence of two populations of cells with different genotypes in one individual), where approximately 20% of the tumor cells showed aberration. This phenomenon may help explain the low signal variations observed in the SNP data.

To assess whether these genomic aberrations affect the gene transcripts, we interrogated a set of 52 primary prostate cancers (Rickman and Rubin, unpublished data), focusing on SNX14, MCM7, and MAF mRNA levels and observed expected trends (Figure 3b), where SNX14 and MCM7 tend to be over-expressed (with p-values < 0.01 and 0.09 - 1-tail) in ERG rearranged cases and MAF tends to be down-regulated (p-value = 0.06, 1-tail).

Analysis of Rearrangement Related Gene Expression for Chromosome/arm Enrichment

Cooperative changes in gene expression levels might be initiated by genomic alterations, as gains or losses, by other non-genomic mechanisms such as transcriptional regulation, or by their combination. Orthogonal datasets of well annotated tissue samples are needed to investigate potential mechanism on large scale. To investigate genomic areas enriched for ERG rearrangement associated transcripts, we analyzed two prostate cancer datasets annotated for ERG rearrangement by FISH analysis and then compared the results with ERG rearrangement associated genomic aberrations. One cohort includes 354 individuals from Sweden (SW) and a second cohort includes 101 individuals from the US (Physician Health Study, PHS) (for details on the cohorts see Setlur et al. (Setlur et al., 2008)). The expression array data set is accessible through GEO–(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

When evaluating chromosomal and chromosomal arm enrichment, we detected significant enrichment values for chromosomes 6 (PHS, p<0.007), 14 (SW, p<0.01) and 21 (PHS, p<0.05), and for 6p (PHS, p<0.05), 6q (PHS, p<0.04), 14q (SW, p<0.01) and 21q (PHS, p<0.05). When considering the deregulation direction (over- or under-expression with respect to ERG rearrangement genotype), we measured significant enrichment scores for over-expression on 2p (SW, p<0.009), 6p (PHS, p<0.009), 6q (SW, p<0.009 and PHS, p<0.01), and 14q (SW, p<0.001). Significant enrichment scores for under-expression are detected on 18p (PHS, p<0.03), and 21q (PHS, q<0.04).

Figure 4a shows the enrichment scores as evaluated for p- and q-arms of each chromosome (x-axis) for the two cohorts, distinguishing between up-regulated and down-regulated rearrangement genes. Only significant p-values are reported. Of interest, chromosome arm 6q is consistently scored significant for enrichment of up-regulated rearrangement-related genes in the two cohorts. The detected genes located on 6q are MYO6 (Myosin VI), SNAP91 (Synaptosomal-associated protein, 91kDa homolog (mouse), AMD1 (Adenosylmethionine decarboxylase 1), HDAC2 (Histone deacetylase 2), MAP3K5 (Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 5), PREP (Prolyl endopeptidase), PTPRK (Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, K), SMPDL3A (Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase, acid-like 3A), MAP7 (Microtubule-associated protein 7), TBP (TATA box binding protein).

Figure 4. Chromosomal arm enrichment for ERG rearrangement related genes.

Two prostate cancer gene expression datasets annotated for ERG rearrangement by FISH analysis were analyzed and compared with genomic aberrations. A, ERG rearrangement enrichment scores derived by gene expression data are presented on y-axis for p and q arms for each chromosome (x-axis). Maximum enrichment score occurs when all genes on a specific arm are associated with rearrangement status. The two cohorts (see text for details) are color coded and directionality of deregulation versus rearrangement status is represented by up and down arrows. Significant p-values, evaluated by the Hypergeometric distribution, are shown. Significant enrichment scores for over-expression were detected for 2p (SW, p<0.009), 6p (PHS, p<0.009), 6q (SW, p<0.009 and PHS, p<0.01), and 14q (SW, p<0.001). Significant enrichment scores for under-expression are detected on 18p (PHS, p<0.03), and 21q (PHS, q<0.04). Interestingly, the 6q arm is consistently scored significant for enrichment of up-regulated rearrangement-related genes in the two cohorts and was shown to harbor a genomic deletion in fusion negative cancers. B. MYO6 (Myosin VI) located 6q14.1 and deregulated in rearrangement positive cancers (see boxplot, left). C. We observed a direct association between over-expression of MYO6 protein (immunohistochemistry evaluation on a tissue microarray, right) and ERG rearrangement status (Fisher exact test p-value = 0.04).

MYO6 was one of the genes included in the 87 gene signature as being up-regulated in ERG rearranged prostate cancers (1-tail p-value = 2.0e-7, see boxplot in Figure 4b) and has been previously implicated as being over expressed in prostate cancer – particularly in higher grade disease (Wei et al., 2008). On an independent set of primary prostate cancers (N=16), half showing ERG rearrangement and half without ERG rearrangement, we evaluated MYO6 protein expression (Figure 4c, see supplemental materials). We observed a direct association between over-expression of MYO6 protein and ERG rearrangement status (Fisher exact test, p-value = 0.04).

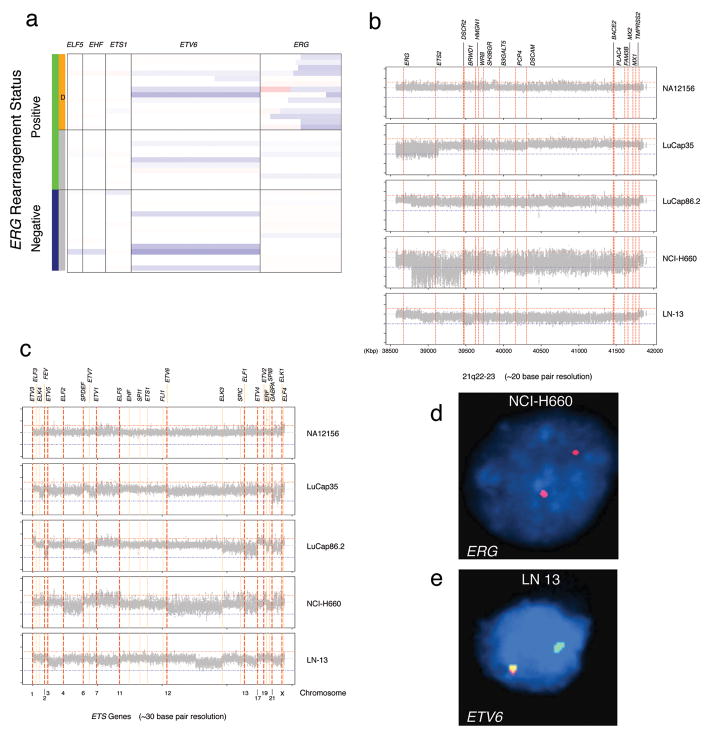

Genomic Aberrations of ETS Genes: the Use of Tiling Arrays for Breakpoint Analysis

The 250K Sty SNP Array offers coverage (more than 5 markers) for a subset of ETS genes, namely ELF5 (E74-like factor 5 ESE-2), EHF (Ets homologous factor), ETS1 (V-Ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog 1 (avian)), ETV6 (Ets variant gene 6 (TEL oncogene)), and ERG (Figure 5a). Interestingly, ETV6, the largest among the ETS genes, undergoes hemizygous deletion in about 25% of prostate cancers. ERG, the most frequent ETS gene involved in fusion event with the androgen regulated TMPRSS2 gene, is represented by 31 SNP markers. As previously reported (Liu et al., 2006; Perner et al., 2006), the interstitial genomic lesion which accounts for about half of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancers exhibits a heterogeneous starting location (Figure 5a). To better investigate the extent of aberrations of the ETS genes and to pin-point TMPRSS2-ERG rearrangements, we designed a custom tiling array chip with one marker every 20–30bp on areas of interest (see Supplemental Table 2) and profiled 4 prostate cancer samples.

Figure 5. Genomic aberrations of ETS genes.

A. 250K Sty SNP Array data for a subset of ETS genes, (i.e., ELF5, EHF, ETS1, ETV6, and ERG) are presented. ETV6 undergoes hemizygous deletion in about 25% of prostate cancers. ERG is represented by 31 SNP markers and demonstrates an interstitial genomic lesion in approximately half of ERG rearranged prostate cancers. B-C. Custom ETS gene tiling arrays with one marker every 20–30bp were used on four prostate cancer samples. Smoothed log2 ratio signals for the four prostate cancer samples and one control (top frames) demonstrate the heterogeneity of the interstitial deletion between ERG and TMPRSS2 as seen in panel B. LuCap35 is characterized by homozygous deletion of ERG and of centromeric portion of ETS2 (39,150Kb) and by hemizygous deletion from ETS2 to PCP4 (Purkinje cell protein 4) (from 39,150Kb to 40,320Kb). The NCI-H660 cell line shows homozygous deletion starting at exon 4 of ERG to ETS2 (from 38,786Kb to 39,440Kb), followed by hemizygous deletion to TMPRSS2. The homozygous deletion observed in NCI-H660, was confirmed by FISH (D). In panel C, the remaining ETS genes were analyzed. We observed that the hormone naïve metastatic lymph node sample (LN13) demonstrated a partial deletion of ETV6, the second most commonly altered ETS gene, starting at 11,813,084bp (chromosome 12). FISH analysis validated the deletion of the telomeric end of ETV6 (E). In addition to ERG, ETS2, and ETV6, we observed aberrations of other ETS genes (i.e., FEV, ELF1, and ERF).

Figure 5b and 5c show smoothed log2 ratio signals for four prostate cancer samples and one control (NA12156, top frames). The heterogeneity of the interstitial deletion between ERG and TMPRSS2 is highlighted in these four samples. LuCap35 is characterized by homozygous deletion of ERG and of centromeric portion of ETS2 (39150 Kb) and by hemizygous deletion from ETS2 to PCP4 (Purkinje cell protein 4) (from 39150 Kb to 40320 Kb). The NCI-H660 cell line shows homozygous deletion starting at exon 4 of ERG to ETS2 (from 38786 Kb to 39440 Kb), followed by hemizygous deletion to TMPRSS2. The high signal variance shown by the cell line is likely explainable by a complex karyotype revealed by M-FISH analysis (See Supplemental Figure 2). The homozygous deletion observed in NCI-H660 was previously confirmed by FISH (Figure 5d; see also SNP data analysis in Figure 2).

When querying all ETS genes, we observed that the hormone naïve metastatic lymph node sample (LN13) shows a partial deletion of ETV6, the second most commonly altered ETS gene, starting at 11813084 bp (chromosome 12). FISH analysis validated the deletion of the telomeric end of ETV6 (Figure 5e). In addition to ERG, ETS2, and ETV6, we observed aberrations of other ETS genes (see Supplemental Table 2), such as FEV (FEV (ETS oncogene family)), ELF1 (E74-like factor 1 (ets domain transcription factor)), and ERF (Ets2 repressor factor).

One major advantage of using a high resolution tiling array is that by narrowing down the breakpoint area, we would be able to identify precise fusion location, as suggested by Korbel et al. (2007). This approach would allow for efficient identification and characterization of various breakpoints observed in the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion. Here we present one example as proof of principle, where we were able to demonstrate the fusion breakpoint for LuCap93 xenograft. By applying BreakPtr to the tiling array data we identified the two putative breakpoint areas, at 38804000 ± 1000 bp and 41792500 ± 2500 bp. This information was used to design a series of primers to identify the exact breakpoint using the vectorette PCR approach and sequencing (Korbel et al., 2007). Supplemental Figure 3 shows the log2 intensity ratio of the area of interest between TMPRSS2 and ERG in the fusion positive xenograft (Panel A), LuCaP 93 and the breakpoint sequencing data (Panel B). The breakpoints were found to be located in introns 3 (Genomic position 38802313 bp) and 1 (Genomic position 41794772 bp) of ERG and TMPRSS2 respectively. The detection of fusion isoform expression as evaluated by RT-PCR showed presence of isoform 3, consistent with the DNA breakpoint (Panel C).

DISCUSSION

Somatic copy number alterations have been shown to be associated with prostate cancer (Saramaki and Visakorpi, 2007). Reported alterations include amplifications of 7q and 8q and deletions of 5q, 6q, 8p, 13q, 16q, 17p, and 18q. These cancer associated chromosomal alterations have been recapitulated in our dataset where we see an accumulation of aberrations with cancer progression. Our observations are in agreement with a recent study from Lapointe et al. (2007), which showed higher number of losses versus gains and accumulation of genomic aberrations in lymph node metastases. A few samples did not show any of the recurrent changes suggesting that non-genomic alterations (epigenetic, transcriptional, and translational) might be responsible for tumorigenesis in these samples. The confounding limitation of stromal contamination has been addressed by exclusion of cases from which infiltrating tumor cells could not be reliably dissected from the surrounding non-tumor tissue. Importantly, this study elucidates the landscape of chromosomal aberrations in the context of fusion prostate cancer, a distinct subclass defined most commonly by fusion of the androgen TMPRSS2 gene and the ETS transcription factor ERG.

High resolution SNP arrays were used to identify common molecular alterations to help distinguish ERG rearranged prostate cancers from non-rearranged prostate cancer. Comparison of the absolute number of lesions detected in non-rearranged cancer versus rearranged cancer did not show a statistically significant difference. This may indicate either that the sample number is limiting or that, number of lesions being equal, separate genomic alterations may be responsible for tumor onset and progression in each of the subclasses. Further, the subclass specific lesions might define the clinical outcome. Although a few of the identified alterations have been shown earlier to be associated with prostate cancer, our study demonstrates that these changes occur specifically in the rearranged or non-rearranged subclasses of prostate cancer.

The loss of 16q has been previously reported to be associated with prostate cancer (Saramaki and Visakorpi, 2007). This loss was seen to occur at a frequency as high as 50% which is similar to the frequency of reported TMPRSS2-ERG fusions in prostate cancer (Matsuyama et al., 2003; Saramaki et al., 2006). The frequency of deletions at 16q24 has also been reported to increase with cancer progression and with metastasis incidence (Matsuyama et al., 2003). Our study demonstrates the specific association of this alteration with the ERG rearranged cancer subclass. Several genes in this area have been implicated to have a tumor suppressor role, with loss leading to cancer progression. The candidate genes that have been reported include MAF (v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene), ATBF1 (AT-binding transcription factor 1), FOXF1 (forkhead box F1), MVD (mevalonate (diphospho) decarboxylase), WFDC1 (WAP four-disulfide core domain 1), WWOX (WW domain containing oxidoreductase), CDH13 (Cadherin 13) and CRISPLD2, (cysteine-rich secretory protein LCCL domain containing 2) (Watson et al., 2004; Saramaki and Visakorpi, 2007). We validated the expression of MAF in our cohort and found its expression to be concomitantly down regulated in the rearranged subclass. MAF (16q23) is a basic zipper transcription factor that belongs to a subfamily of large MAF proteins and interacts with other transcription factors with the basic zipper motif to mediate both gene activation and repression. It is believed to act as an oncogene after undergoing translocation with the IgH locus (14q32) (Chesi et al., 1998). This translocation is observed in approximately 2% of multiple myelomas. MAF is believed to interact with Cyclin D2 which is overexpressed in cases with translocations leading to increased tumor proliferation, and a poorer clinical outcome. Although the molecular mechanisms of MAF proteins are not well understood, one study reports that overexpression of MAF leads to downregulation of BCL2 expression and increase in apoptosis upon interaction with MYB (Peng et al., 2007). The fact that this gene is down regulated in our dataset suggests that cell viability is enhanced in tumors with MAF deletion. This is further supported by the fact that MAF has a tumor suppressor role since it participates in TP53 mediated cell death (Hale et al., 2000). MAFA, a member of the MAF family, maps to the frequently amplified 8q24.3 region found in prostate cancer (Saramaki and Visakorpi, 2007), hence suggesting a different mode of action for this member of the MAF subfamily. Interestingly, MAFB, another member of this subfamily, interacts with the ETS transcription factor ETS1 to inhibit erythroid differentiation (Sieweke et al., 1996). Hence it appears that the deletion of the MAF tumor suppressor gene in the ERG rearranged subclass facilitates tumor progression by inhibition of the apoptotic pathways.

The second ERG rearranged cancer-specific aberration, amplification of 7q, is one of the earliest reported chromosomal events associated with prostate cancer (Saramaki and Visakorpi, 2007). In particular, recent studies have demonstrated amplification of MCM7 in approximately 50% of aggressive prostate cancers and 20% in indolent tumors (Ren et al., 2006). They also demonstrated a good correlation between transcript expression, protein expression and gene amplification of MCM7. A recent study demonstrated MCM7 as being significantly associated with prostate cancer progression (Laitinen et al., 2008). MCM7 is part of a complex of genes that plays a key role in controlling DNA replication (Homesley et al., 2000) and has been implicated to be involved in tumorigenesis (Honeycutt et al., 2006). No previous evidence has been reported on association of ERG rearranged prostate cancer with gain of 7q. We also found a corresponding upregulation of the transcript expression in our samples. Interestingly, the MCM7 gene also contains a microRNA miR-106b-25 cluster which is overexpressed in prostate cancer (Ambs et al., 2008). miR-106b-25 acts as a modulator of the TGFβ pathway where it suppresses the expression of CDKN1A (p21), a cell cycle inhibitor downstream of TGFβ which is also a target of MYC. Since MYC is seen to be amplified in prostate cancer, it suggests a co-operative effect at the genomic level that leads to inhibition of the TGFβ tumor suppressor pathway. In addition, the transcription factor E2F1 regulates the expression of both MCM7 and miR-106b-25. E2F1 in turn is regulated by miR-106b-25 in a negative feedback loop. Hence, it remains to be established if overexpression of the miRNA or amplification of MCM7 or both contributes to the oncogenic event at this locus. If indeed the miRNA is involved in tumor progression, antisense oligos designed against miR-106b-25 would be potential candidates to treat tumors with ERG rearrangement.

The non-rearranged cancers showed enrichment for deletion in 6q. Studies have reported a deletion frequency of 24–50% (Alers et al., 2001; El Gedaily et al., 2001). SNX14, which maps to this region, was seen to have a single copy deletion by FISH. A corresponding reduction in transcript expression was seen in the non-rearranged cases. SNX14 is associated with the endoplasmic reticulum and may play a role in receptor trafficking (Carroll et al., 2001). The protein contains a regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) domain. This is the first report of association of this gene with prostate cancer. In addition, analysis of the ERG rearrangement associated gene expression signature showed an enrichment of upregulated genes mapping to 6q in the ERG rearranged subclass. Among the 6q genes that showed striking differences between rearranged and non- rearranged cancer was MYO6 which is preferentially expressed in rearranged cancers. MYO6 is an actin motor involved in intracellular vesicle trafficking and transport. It was proposed to be an early marker for prostate cancer since its expression was seen to be high in PIN lesions. It has been suggested that overexpression of MYO6 may promote tumor growth and invasion (Knudsen, 2006). It has also been demonstrated to be associated with distinct changes in the Golgi apparatus and is co-expressed with GOLM1 (Golgi membrane protein 1), a gene involved in prostate cancer progression (Wei et al., 2008). Hence the genes at this locus appear to be involved in the modulation of protein trafficking.

In determining the frequency of molecular alterations using SNP array analysis, one important limitation has to do with the issue of sampling. The SNP array data used in the current study interrogates pools of tumor cells that also contain other cell types such as endothelial and stromal cells. The FISH assays are able to assess a specific genomic result -albeit at a lower resolution- on individual cells. We would view the FISH data presented in the current study as the Gold Standard and the SNP data as the hypothesis generating whole genome discovery dataset. Future studies using the FISH assays developed in this study for validation on larger clinical cohorts will be better suited to address the actual frequency of the lesions found to be associated with ERG rearrangement.

Our observation on associations between ERG rearranged prostate cancer and 16q and 6q alterations is consistent with the results from Lapointe et al. (2007), where 16q deletion is in the same category as TMPRSS2-ERG fusion by deletion whereas 6q deletion is found in the less aggressive subtype. Previously, Tomlins et al. (2007) reported on the enrichment of ETS fusion prostate cancer related genes on 6q21 using ETS overexpression as a surrogate for ETS rearrangements. They suggested a cooperative amplification at 6q21 in ETS rearranged tumors or loss of 6q21 in ETS non-rearranged tumors and hypothesized that down-regulation of genes at 6q21 may be important to tumor development in ETS non-rearranged prostate cancers. Here, we present direct evidence of association of 6q DNA copy number alteration with the prostate cancer subclasses and the corresponding deregulation of gene expression. Interestingly, the reported frequencies of all the ERG rearranged cancer specific genomic alterations identified by our study are in agreement with the frequencies of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion incidence.

We originally introduced the break apart assay for ERG rearrangements (Tomlins et al., 2005) because the genomic distance between TMPRSS2 and ERG was 3 MB (Perner et al., 2006) and thus too small to develop a reliable fusion assay using BAC probe-based FISH. However, the ERG break-apart assay only indirectly assesses that ERG is fused to TMPRSS2. In the vast majority of cases, ERG break apart is a surrogate for TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion as previously demonstrated by RT-PCR (Tomlins et al., 2005). One limitation of the ERG break apart assay is that other 5 prime partners than TMPRSS2 could give the same result. Based on unpublished observations, we estimate that this may occur in at most 5–10% of cases with ERG rearrangement. Specifically, we have seen ERG break apart with SLC45A3 being the 5 prime partner in 5% of over 550 prostate cancer cases analyzed on a clinical cohort from Berlin. Therefore, while ERG break apart is an indirect assay, it only misclassifies a small percentage of cases. The parallel use of other break apart assays targeting the 5 prime partners such as TMPRSS2 and SLC45A3 would help clarify these cases.

The use of custom tiling arrays further allowed us to interrogate the various ETS genes. Some of the ETS genes showed changes in the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion positive samples tested. One of the aberrations involved a complete/partial deletion of ETV6. The product of ETV6 contains two functional domains: an N-terminal pointed (PNT) domain that is involved in the protein-protein interactions with itself and other proteins, and a C-terminal DNA-binding domain. Gene knockout studies in mice suggest that it is required for hematopoiesis and maintenance of the developing vascular network. This gene is known to be involved in a large number of chromosomal rearrangements associated with leukemia and congenital fibrosarcoma. This gene has been reported to be frequently deleted or mutated in prostate cancer (Kibel et al., 2002) suggesting that it may act as a tumor suppressor with inactivation leading to cancer progression. The tiling array also proved to be an efficient method for mapping the exact TMPRSS2-ERG fusion breakpoints. In the case EWS rearrangements in leukemia, the genomic breakpoints have been determined to be tightly clustered for the EWS locus (<8 Kb region), whereas the breakpoints of its partner FLI1, occurs over a larger 35 Kb region in Ewing’s family tumors (Delattre et al., 1992). To date, 12 distinct EWS-FLI1 rearrangements have been described each containing variable combinations of exons flanking the DNA fusion point (Zucman et al., 1993; Zoubek et al., 1994). Therefore, even within a specific EWS rearrangement subclass such as EWS-FLI1, slightly different fusion proteins are produced. The result may lead to variations in the protein fusion product with respect to protein structure and activity as an oncogene. From a clinical perspective, these variant fusion proteins may be associated with different prognostic significance (Zoubek et al., 1996; de Alava et al., 1998).

Hence using high resolution arrays we were able to determine the genomic alterations specific to the ETS fusion subclass of prostate cancer. The approach of combining the genomic data with the gene expression will facilitate a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms that lead to tumor progression.

Supplementary Material

Genomic aberrations detected on advanced tumor samples profiled using 100K Affymetrix Array indicate overall agreement with the current study findings. In addition, these results support the view that prostate tumors accumulate gains over time. Q-values are plotted along the genomic location. The blue line indicates results obtained on tissue samples and xenografts; the black line on tissue samples.

M-FISH performed on the cell line NCI-H660 revealed a complex karyotype indicating a high degree of genomic instability. Most cells analyzed showed greater than two copies of each chromosome (consistent with whole chromosome gains observed in the SNP data), with the exception of chromosomes 21 and X. This cell line showed a complete loss of the Y chromosome. In addition, several chromosomes appeared to be mosaic. This figure is a representative image of the cells that were analyzed.

RTPCR using a forward primer in TMPRSS2 exon 1 and a reverse primer in ERG exon 6 revealed that TMPRSS2-ERG transcript variant III (TMPRSS2 exon 1 joined to ERG exon 4 resulting in a PCR fragment at 509 bp) is expressed in LuCaP93 (lane 1). The TMPRSS2-ERG positive prostate cancer cell line VCaP (lane 2) and a human prostate cancer sample 1701_A (lane 3) served as positive controls as both express variant III (confirmed by sequencing of the PCR product). The fusion negative prostate cancer cell line PC-3 (lane 4) and a water control (lane 5) served as negative controls. All RT-PCRs were done with 50ng of cDNA in a final volume of 50ul. 10ul of each RT-PCR was loaded.

Acknowledgments

Supported by: Grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA116337 and R01CA125612 to MAR and FD, R01CA109038 to MM, 5K08CA122833-02 to RB) and the Department of Defense (PCO40715 to MAR and FD).

The authors like to acknowledge xenograft samples provided by Robert Vessella and Larry True from the University of Washington, Gad Getz for fruitful discussion on bioinfomatics aspects, and Kirsten D Mertz for characterization of NCI-H660 cell line and xenografts.

References

- Alers JC, Krijtenburg PJ, Vis AN, Hoedemaeker RF, Wildhagen MF, Hop WC, van Der Kwast TT, Schroder FH, Tanke HJ, van Dekken H. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of prostatic adenocarcinomas from screening studies: early cancers may contain aggressive genetic features. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:399–406. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63983-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambs S, Prueitt RL, Yi M, Hudson RS, Howe TM, Petrocca F, Wallace TA, Liu CG, Volinia S, Calin GA, Yfantis HG, Stephens RM, Croce CM. Genomic profiling of microRNA and messenger RNA reveals deregulated microRNA expression in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6162–6170. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin MB, Grignon DJ, Humphrey PA, Srigley JR. Gleason Grading of Prostate Cancer: a contemporary approach. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2003. p. 116. [Google Scholar]

- Attard G, Clark J, Ambroisine L, Fisher G, Kovacs G, Flohr P, Berney D, Foster CS, Fletcher A, Gerald WL, Moller H, Reuter V, De Bono JS, Scardino P, Cuzick J, Cooper CS. Duplication of the fusion of TMPRSS2 to ERG sequences identifies fatal human prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:253–263. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beroukhim R, Getz G, Nghiemphu L, Barretina J, Hsueh T, Linhart D, Vivanco I, Lee JC, Huang JH, Alexander S, Du J, Kau T, Thomas RK, Shah K, Soto H, Perner S, Prensner J, Debiasi RM, Demichelis F, Hatton C, Rubin MA, Garraway LA, Nelson SF, Liau L, Mischel PS, Cloughesy TF, Meyerson M, Golub TA, Lander ES, Mellinghoff IK, Sellers WR. Assessing the significance of chromosomal aberrations in cancer: Methodology and application to glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20007–20012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710052104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll P, Renoncourt Y, Gayet O, De Bovis B, Alonso S. Sorting nexin-14, a gene expressed in motoneurons trapped by an in vitro preselection method. Dev Dyn. 2001;221:431–442. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesi M, Bergsagel PL, Shonukan OO, Martelli ML, Brents LA, Chen T, Schrock E, Ried T, Kuehl WM. Frequent dysregulation of the c-maf proto-oncogene at 16q23 by translocation to an Ig locus in multiple myeloma. Blood. 1998;91:4457–4463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alava E, Kawai A, Healey JH, Fligman I, Meyers PA, Huvos AG, Gerald WL, Jhanwar SC, Argani P, Antonescu CR, Pardo-Mindan FJ, Ginsberg J, Womer R, Lawlor ER, Wunder J, Andrulis I, Sorensen PH, Barr FG, Ladanyi M. EWS-FLI1 fusion transcript structure is an independent determinant of prognosis in Ewing’s sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1248–1255. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delattre O, Zucman J, Plougastel B, Desmaze C, Melot T, Peter M, Kovar H, Joubert I, de Jong P, Rouleau G, Aurias A, Thomas G. Gene fusion with an ETS DNA-binding domain caused by chromosome translocation in human tumours. Nature. 1992;359:162–165. doi: 10.1038/359162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demichelis F, Fall K, Perner S, Andren O, Schmidt F, Setlur SR, Hoshida Y, Mosquera JM, Pawitan Y, Lee C, Adami HO, Mucci LA, Kantoff PW, Andersson SO, Chinnaiyan AM, Johansson JE, Rubin MA. TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion associated with lethal prostate cancer in a watchful waiting cohort. Oncogene. 2007;26:4596–4599. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demichelis F, Greulich H, Macoska JA, Beroukhim R, Sellers WR, Garraway L, Rubin MA. SNP panel identification assay (SPIA): a genetic-based assay for the identification of cell lines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2446–2456. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Gedaily A, Bubendorf L, Willi N, Fu W, Richter J, Moch H, Mihatsch MJ, Sauter G, Gasser TC. Discovery of new DNA amplification loci in prostate cancer by comparative genomic hybridization. Prostate. 2001;46:184–190. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20010215)46:3<184::aid-pros1022>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, Thun M. Cancer statistics, 2001. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:15–36. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale TK, Myers C, Maitra R, Kolzau T, Nishizawa M, Braithwaite AW. Maf transcriptionally activates the mouse p53 promoter and causes a p53-dependent cell death. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17991–17999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000921200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson BE, Tomlins SA, Shah N, Laxman B, Cao Q, Prensner JR, Cao X, Singla N, Montie JE, Varambally S, Mehra R, Chinnaiyan AM. Characterization of TMPRSS2:ETV5 and SLC45A3:ETV5 gene fusions in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:73–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer MD, Kuefer R, Huang W, Li H, Bismar TA, Perner S, Hautmann RE, Sanda MG, Gschwend JE, Rubin MA. Prognostic factors in lymph node-positive prostate cancer. Urology. 2006;67:1016–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homesley L, Lei M, Kawasaki Y, Sawyer S, Christensen T, Tye BK. Mcm10 and the MCM2-7 complex interact to initiate DNA synthesis and to release replication factors from origins. Genes Dev. 2000;14:913–926. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honeycutt KA, Chen Z, Koster MI, Miers M, Nuchtern J, Hicks J, Roop DR, Shohet JM. Deregulated minichromosomal maintenance protein MCM7 contributes to oncogene driven tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2006;25:4027–4032. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupe P, Stransky N, Thiery JP, Radvanyi F, Barillot E. Analysis of array CGH data: from signal ratio to gain and loss of DNA regions. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3413–3422. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibel AS, Faith DA, Bova GS, Isaacs WB. Mutational analysis of ETV6 in prostate carcinoma. Prostate. 2002;52:305–310. doi: 10.1002/pros.10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen B. Migrating with myosin VI. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1523–1526. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbel JO, Urban AE, Grubert F, Du J, Royce TE, Starr P, Zhong G, Emanuel BS, Weissman SM, Snyder M, Gerstein MB. Systematic prediction and validation of breakpoints associated with copy-number variants in the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10110–10115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703834104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen S, Martikainen PM, Tolonen T, Isola J, Tammela TL, Visakorpi T. EZH2, Ki-67 and MCM7 are prognostic markers in prostatectomy treated patients. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:595–602. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe J, Li C, Giacomini CP, Salari K, Huang S, Wang P, Ferrari M, Hernandez-Boussard T, Brooks JD, Pollack JR. Genomic profiling reveals alternative genetic pathways of prostate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8504–8510. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leprince D, Gegonne A, Coll J, de Taisne C, Schneeberger A, Lagrou C, Stehelin D. A putative second cell-derived oncogene of the avian leukaemia retrovirus E26. Nature. 1983;306:395–397. doi: 10.1038/306395a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Hung Wong W. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: model validation, design issues and standard error application. Genome Biol. 2001;2:RESEARCH0032. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-8-research0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Chang B, Sauvageot J, Dimitrov L, Gielzak M, Li T, Yan G, Sun J, Adams TS, Turner AR, Kim JW, Meyers DA, Zheng SL, Isaacs WB, Xu J. Comprehensive assessment of DNA copy number alterations in human prostate cancers using Affymetrix 100K SNP mapping array. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:1018–1032. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama H, Pan Y, Yoshihiro S, Kudren D, Naito K, Bergerheim US, Ekman P. Clinical significance of chromosome 8p, 10q, and 16q deletions in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2003;54:103–111. doi: 10.1002/pros.10173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertz KD, Setlur SR, Dhanasekaran SM, Demichelis F, Perner S, Tomlins S, Tchinda J, Laxman B, Vessella RL, Beroukhim R, Lee C, Chinnaiyan AM, Rubin MA. Molecular characterization of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in the NCI-H660 prostate cancer cell line: a new perspective for an old model. Neoplasia. 2007;9:200–206. doi: 10.1593/neo.07103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera JM, Perner S, Demichelis F, Kim R, Hofer MD, Mertz KD, Paris PL, Simko J, Collins C, Bismar TA, Chinnaiyan AM, Rubin MA. Morphological features of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2007;212:91–101. doi: 10.1002/path.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S, Lalani S, Leavenworth JW, Ho IC, Pauza ME. c-Maf interacts with c-Myb to down-regulate Bcl-2 expression and increase apoptosis in peripheral CD4 cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2868–2880. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perner S, Demichelis F, Beroukhim R, Schmidt FH, Mosquera JM, Setlur S, Tchinda J, Tomlins SA, Hofer MD, Pienta KG, Kuefer R, Vessella R, Sun XW, Meyerson M, Lee C, Sellers WR, Chinnaiyan AM, Rubin MA. TMPRSS2:ERG fusion-associated deletions provide insight into the heterogeneity of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8337–8341. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren B, Yu G, Tseng GC, Cieply K, Gavel T, Nelson J, Michalopoulos G, Yu YP, Luo JH. MCM7 amplification and overexpression are associated with prostate cancer progression. Oncogene. 2006;25:1090–1098. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royce TE, Rozowsky JS, Gerstein MB. Assessing the need for sequence-based normalization in tiling microarray experiments. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:988–997. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saramaki O, Visakorpi T. Chromosomal aberrations in prostate cancer. Front Biosci. 2007;12:3287–3301. doi: 10.2741/2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saramaki OR, Porkka KP, Vessella RL, Visakorpi T. Genetic aberrations in prostate cancer by microarray analysis. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1322–1329. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlur SR, Mertz KD, Hoshida Y, Demichelis F, Lupien M, Perner S, Sboner A, Pawitan Y, Andren O, Johnson LA, Tang J, Adami HO, Calza S, Chinnaiyan AM, Rhodes D, Tomlins S, Fall K, Mucci LA, Kantoff PW, Stampfer MJ, Andersson SO, Varenhorst E, Johansson JE, Brown M, Golub TR, Rubin MA. Estrogen-Dependent Signaling in a Molecularly Distinct Subclass of Aggressive Prostate Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:815–825. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieweke MH, Tekotte H, Frampton J, Graf T. MafB is an interaction partner and repressor of Ets-1 that inhibits erythroid differentiation. Cell. 1996;85:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlins SA, Laxman B, Dhanasekaran SM, Helgeson BE, Cao X, Morris DS, Menon A, Jing X, Cao Q, Han B, Yu J, Wang L, Montie JE, Rubin MA, Pienta KJ, Roulston D, Shah RB, Varambally S, Mehra R, Chinnaiyan AM. Distinct classes of chromosomal rearrangements create oncogenic ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer. Nature. 2007;448:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nature06024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlins SA, Mehra R, Rhodes DR, Smith LR, Roulston D, Helgeson BE, Cao X, Wei JT, Rubin MA, Shah RB, Chinnaiyan AM. TMPRSS2:ETV4 gene fusions define a third molecular subtype of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3396–3400. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, Sun XW, Varambally S, Cao X, Tchinda J, Kuefer R, Lee C, Montie JE, Shah RB, Pienta KJ, Rubin MA, Chinnaiyan AM. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban AE, Korbel JO, Selzer R, Richmond T, Hacker A, Popescu GV, Cubells JF, Green R, Emanuel BS, Gerstein MB, Weissman SM, Snyder M. High-resolution mapping of DNA copy alterations in human chromosome 22 using high-density tiling oligonucleotide arrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4534–4539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511340103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JE, Doggett NA, Albertson DG, Andaya A, Chinnaiyan A, van Dekken H, Ginzinger D, Haqq C, James K, Kamkar S, Kowbel D, Pinkel D, Schmitt L, Simko JP, Volik S, Weinberg VK, Paris PL, Collins C. Integration of high-resolution array comparative genomic hybridization analysis of chromosome 16q with expression array data refines common regions of loss at 16q23-qter and identifies underlying candidate tumor suppressor genes in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:3487–3494. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S, Dunn TA, Isaacs WB, De Marzo AM, Luo J. GOLPH2 and MYO6: putative prostate cancer markers localized to the Golgi apparatus. Prostate. 2008;68:1387–1395. doi: 10.1002/pros.20806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto M, Cunha IW, Coudry RA, Fonseca FP, Torres CH, Soares FA, Squire JA. FISH analysis of 107 prostate cancers shows that PTEN genomic deletion is associated with poor clinical outcome. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:678–685. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoubek A, Dockhorn-Dworniczak B, Delattre O, Christiansen H, Niggli F, Gatterer-Menz I, Smith TL, Jurgens H, Gadner H, Kovar H. Does expression of different EWS chimeric transcripts define clinically distinct risk groups of Ewing tumor patients? J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1245–1251. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.4.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoubek A, Pfleiderer C, Salzer-Kuntschik M, Amann G, Windhager R, Fink FM, Koscielniak E, Delattre O, Strehl S, Ambros PF. Variability of EWS chimaeric transcripts in Ewing tumours: a comparison of clinical and molecular data. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:908–913. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucman J, Melot T, Desmaze C, Ghysdael J, Plougastel B, Peter M, Zucker JM, Triche TJ, Sheer D, Turc-Carel C, Ambros P, Combaret V, Lenoir G, Aurias A, Thomas G, Delattre O. Combinatorial generation of variable fusion proteins in the Ewing family of tumours. Embo J. 1993;12:4481–4487. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Genomic aberrations detected on advanced tumor samples profiled using 100K Affymetrix Array indicate overall agreement with the current study findings. In addition, these results support the view that prostate tumors accumulate gains over time. Q-values are plotted along the genomic location. The blue line indicates results obtained on tissue samples and xenografts; the black line on tissue samples.

M-FISH performed on the cell line NCI-H660 revealed a complex karyotype indicating a high degree of genomic instability. Most cells analyzed showed greater than two copies of each chromosome (consistent with whole chromosome gains observed in the SNP data), with the exception of chromosomes 21 and X. This cell line showed a complete loss of the Y chromosome. In addition, several chromosomes appeared to be mosaic. This figure is a representative image of the cells that were analyzed.

RTPCR using a forward primer in TMPRSS2 exon 1 and a reverse primer in ERG exon 6 revealed that TMPRSS2-ERG transcript variant III (TMPRSS2 exon 1 joined to ERG exon 4 resulting in a PCR fragment at 509 bp) is expressed in LuCaP93 (lane 1). The TMPRSS2-ERG positive prostate cancer cell line VCaP (lane 2) and a human prostate cancer sample 1701_A (lane 3) served as positive controls as both express variant III (confirmed by sequencing of the PCR product). The fusion negative prostate cancer cell line PC-3 (lane 4) and a water control (lane 5) served as negative controls. All RT-PCRs were done with 50ng of cDNA in a final volume of 50ul. 10ul of each RT-PCR was loaded.