Abstract

The NF-κB family of transcription factors consists of fifteen possible dimers whose activity is controlled by a family of inhibitor proteins, known as IκBs. A variety of cellular stimuli, many of them transduced by members of the TNFR superfamily, induce degradation of IκBs to activate an overlapping subset of NF-κB dimers. However, generation and stimulus-responsive activation of NF-κB dimers are intimately linked via various cross-regulatory mechanisms that allow crosstalk between different signaling pathways through the NF-κB signaling system. In this review, we summarize these mechanisms and discuss physiological and pathological consequences of crosstalk between apparently distinct inflammatory and developmental signals. We argue that a systems approach will be valuable for understanding questions of specificity and emergent properties of highly networked cellular signaling systems.

Keywords: organogenesis, inflammation, NF-κB, system emergent properties, mathematical modeling

1. Introduction

1.1 The TNF Receptor Superfamily

The tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily comprises more than two dozen members. Their primary physiological functions appear to be in the immune system, both in the development of specialized immune cells and organs, and in the immune response to pathogens. Many TNFR superfamily members and their extra-cellular ligands have been shown to play critical roles in the organization of the spleen, the development of lymph nodes and thymus, and maturation of T-cells and B-cells within these organs. The lymphotoxin beta receotor (LTβR), for example, is critical for secondary lymphoid organ development, while signaling emanating from BAFFR is important for B-cell survival and maturation. Other TNFR superfamily members are critical for mediating inflammatory responses that may be initiated by pathogen sensing receptors of the TLR superfamily. TNFR superfamily members also play important roles in coordinating innate and adaptive immune responses. For example, two TNF receptors, TNFR1 and TNFR2, mediate the function of the proinflammatory cytokine TNF, and CD40R initiates a powerful B-cell proliferation and activation program upon binding of the ligand CD40L produced by innate immune or antigen presenting cells. Though the distinction between immune development and immune response processes seems intuitive, a variety of observations point towards links between them. One focus of this review will be the signaling crosstalk between the molecular pathways that mediate immune responses and those that mediate immune developmental processes.

1.2 The NF-κB Signaling System

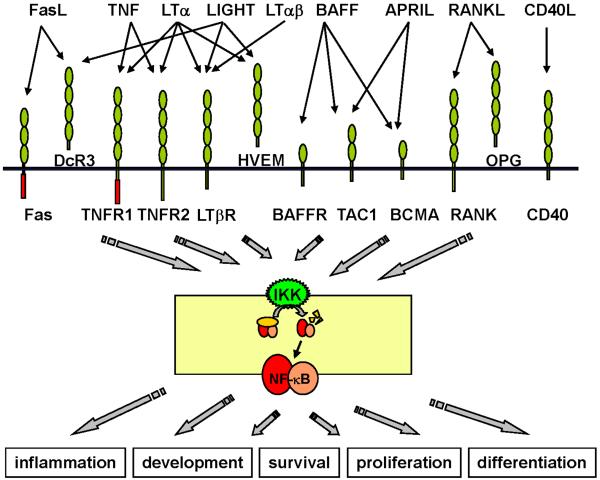

The signaling system that controls the activity of Nuclear Factor kappaB (NF-κB) is responsive to virtually all TNFR superfamily members (Fig. 1). NF-κB activity consists of a family of dimeric transcription factors. Five related mammalian NF-κB proteins, namely RelA/p65, RelB, cRel/Rel, p50 and p52, can potentially form fifteen different homo- or heterodimeric complexes (Hoffmann and Baltimore, 2006). The NF-κB proteins share an approximately 300 amino acid Rel Homology Region (RHR), which comprises domains for DNA binding, dimerization and nuclear localization. NF-κB dimers bind to the promoters of a variety of genes via a sequence element termed the kappaB (κB) site, which exhibits a loose consensus 5'-GGRNN(WYYCC)-3' (where R= purine, N= any base, W= adenine or thymine and Y = pyrimidine). Sequence heterogeneity confers specificity to the promoters via differential utilization of specific NF-κB isoforms (Hoffmann and Baltimore, 2006).

Fig. 1. The TNF receptor super-family and the NF-κB signaling system.

Various members of the TNF receptor super-family utilize the NF-κB signaling pathway to effect diverse physiological responses through NF-κB dependent gene expression program. The stimulus-specificity of the cellular response and the functional interaction of distinct stimuli via the NF-κB signaling system is the focus of this review.

Five proteins have also been identified that can inhibit NF-κB activity. These include three inhibitors of NF-κB (IκBs), namely IκBα, -β and -ε (Li and Nabel, 1997; Whiteside et al., 1997; Zabel and Baeuerle, 1990), and two NF-κB precursor proteins, namely nfkb1 p105 and nfkb2 p100. Common to all five NF-κB inhibitors is the ankyrin repeat domain (ARD), which masks NF-κB DNA binding and nuclear translocation sequences (Huxford et al., 1998). NF-κB activation is achieved through stimulus-responsive proteolysis of the inhibitors. In fact, two mechanisms were originally proposed to account for the NF-κB activation (Baeuerle and Baltimore, 1988a): (a) existence of latent activity bound to a separate inhibitor that releases NF-κB dimer during signaling, and (b) a precursor processing mechanism that generates active NF-κB dimer. The distinction between these two activation mechanisms, as discussed later, continues to be relevant to our current understanding of NF-κB signaling.

2. The canonical NF-κB signaling pathway

2.1 Latent NF-κB/RelA:p50 dimer bound to IκBs

The primary mediator of NF-κB function in most cell types is the RelA:p50 dimer. A C-terminal domain of RelA renders this heterodimer a potent transcriptional activator. The detergent deoxycholate was found to liberate kappaB DNA binding activity in the cytoplasmic extract prepared from the unstimulated cells, confirming the existence of latent NF-κB/RelA:p50 that is bound to inhibitor(s) (Baeuerle and Baltimore, 1988b), that were later identified as the three canonical or classical IκBs, IκBα, -β and -ε. These inhibitors were also shown to retain cRel-containing dimers and regulate their activation.

2.2 Activation and termination of canonical NF-κB response

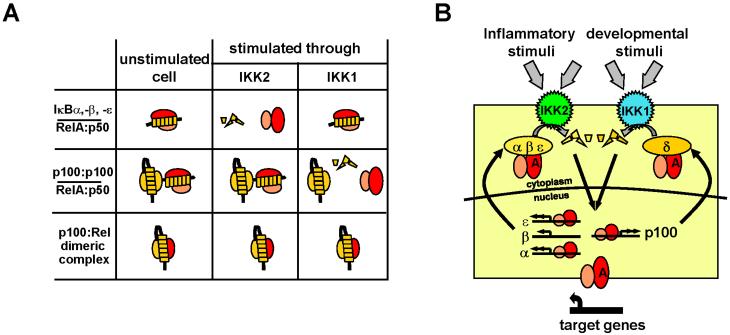

NF-κB/RelA:p50 dimer activation through the classical or the canonical pathway, such as those transduced through TNFR1, involves signal responsive activation of IkappaB kinase (IKK). The IKK complex is composed of two catalytic subunits, IKK1/IKKα and IKK2/IKKβ and several regulatory subunits, including the NF-kappaB Essential Modulator, NEMO. In general, the catalytic activity of IKK2 is required for canonical signaling (Ghosh and Karin, 2002; Scheidereit, 2006). In response to a variety of inflammatory stimuli, the IKK complex phosphorylates IκBs at specific N-terminal serine residues (serine 32 and serine 36 for IκBα). Subsequent β-TrCP-mediated ubiquitination of canonical IκBs promotes complete proteasomal degradation of the inhibitors to liberate bound NF-κB dimers (Karin and Ben-Neriah, 2000) (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, neither phosphorylation nor ubiquitination is sufficient to dissociate IκBs from the RelA:p50 dimer and proteasomal degradation of IκBs is absolutely required for RelA:p50 nuclear translocation (DiDonato et al., 1995). This mode of NF-κB activation in the canonical pathway is protein synthesis-independent. NF-κB transcriptional activity is thought to be further modulated through phosphorylation and other post-transcriptional modifications of RelA (Neumann and Naumann, 2007), but a clear understanding that relates RelA modification with its function is yet to emerge.

Fig. 2. Inhibited NF-κB complexes and their activation through the four IκB containing NF-κB signaling module.

(A) A schematic depiction of stimulus responsive and unresponsive NF-κB complexes. Signal responsive NF-κB/RelA:p50 dimers are bound to either canonical IκBs, IκBα, -β, -ε, or to the non-canonical IκBδ/asymmetric (p100)2. Inflammatory stimuli signal through the IKK2/IKKβ to catalyze phosphorylation of canonical IκBs directing them to proteasome-mediated degradation to release the bound RelA:p50 dimers into the nucleus. In contrast, the developmental cues signal through the IKK1/IKKα to mediate phosphorylation and degradation of IκBδ to result in nuclear translocation of the bound RelA:p50 dimers. In contrast, auto-inhibited dimeric complexes of p100 and other Rel proteins are signal unresponsive. (B) A mathematical model that describes inflammatory IKK2 mediated degradation of IκBα, -β and -ε and developmental IKK1 mediated degradation of IκBδ to release the bound NF-κB/RelA:p50 dimer into the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, NF-κB/RelA:p50 dimer activates transcription of many genes that include NF-κB inhibitors, IκBα, IκBε and IκBδ, thereby, orchestrating an example of feedback-inhibition loop. The yellow box depicts the scope of the current version of a mathematical model (Basak et al., 2007) that is capable of recapitulating NF-κB/RelA:p50 dimer activation in response to TNFR and LTβR signaling. The model contains 98 differential equations representing interactions between RelA;p50, IκBα, IκBβ, IκBε, IκBδ, IKK1 and IKK2, synthesis and degradation of IκB proteins and mRNA, nuclear-cytoplasmic transport of these components and their complexes.

Interestingly, genes encoding IκBα and IκBε are also NF-κB target genes. Therefore, NF-κB activation generates feedback inhibition within the pathway, whereby re-synthesized IκBs sequester nuclear NF-κB dimers and mediate nuclear export of the inhibited NF-κB dimers to ensure appropriate termination of the canonical NF-κB response.

2.3 NF-κB signaling dynamics and a mathematical model

As a result of IκB-mediated negative feedback regulation, inflammatory stimuli result in NF-κB/RelA:p50 activity that shows complex temporal regulation. A detailed understanding of these biochemical events has allowed for the construction of a mathematical model that recapitulates the experimentally observed NF-κB activation dynamics during the TNF response (Hoffmann et al., 2002; Kearns et al., 2006). This mathematical model provided an in silico confirmation that the known biochemical mechanisms, such as stimulus-responsive degradation and resynthesis of IκBs, its association/dissociation with the RelA:p50 dimer, nuclear import and export of free and IκB-bound RelA:p50 dimers, are sufficient to explain the observed NF-κB regulation in response to the canonical pathway activation (Fig. 2B). By combining computation and biochemical analyses, the mathematical model was further refined to capture NF-κB signaling dynamics during TLR4 signaling (Covert et al., 2005; Werner et al., 2005).

3. Immune response regulation by the canonical NF-κB pathway

3.1 Canonical NF-κB activation during immune response

Innate immunity represents a first defense to pathogen infection, followed by adaptive immune responses. Pathogen associated molecular pattern (PAMP) recognition by epithelial or tissue resident hematopoietic cells induces expression of cytokines, which act as mediators of inflammation to recruit phagocytic cells for pathogen clearance. Interestingly, all known PAMPs induce IκB phosphorylation and RelA:p50 activation, and the resulting inflammatory cytokines are also potent inducers of the canonical NF-κB pathway. TNF, in particular, plays a prominent role in this positive autocrine and paracrine feedback. In addition, T-cell activation upon TCR signaling, B-cell activation upon BCR and CD40R engagement also involve NF-κB RelA:p50 activation. Therefore, the canonical NF-κB pathway appears to be intimately linked with the mounting and propagation of both innate and adaptive immune responses.

3.2 Mouse genetics indicate diverse canonical NF-κB functions in immunity

Mouse knockout studies have corroborated that NF-κB has an important role in immune responses. Initially, the embryonic lethality of rela-/- mice due to massive hepatocyte apoptosis (Beg et al., 1995) revealed a novel function of RelA:p50 as an anti-apoptotic regulator but presented obstacles for genetically assessing RelA's function in the immune system. When the lethality was rescued upon combined inactivation of the gene encoding TNFR1, the resulting rela-/-tnfr1-/- mice showed an increased susceptibility to bacterial infection and succumbed to neonatal death (Alcamo et al., 2001). Radiation chimeras that were reconstituted with RelA/TNFR1 deficient hematopoietic cells, also indicated a role for RelA in mounting immune responses.

Deficiency in NF-κB component p50 resulted in reduced levels of serum immunoglobulins in nfkb1-/- mice, indicating a role for the canonical pathway in humoral responses. In addition, B-cells derived from nfkb1-/-, rela-/-tnfr1-/- or crel-/- mice exhibited proliferation defects in vitro (Alcamo et al., 2002; Kontgen et al., 1995; Sha et al., 1995). Similar studies have also established an important role for canonical NF-κB dimers in thymocyte maturation (Boothby et al., 1997), T-cell proliferation, survival and in vivo function (Zheng et al., 2003), and in dendritic cell development (Ouaaz et al., 2002). In sum, these genetic analyses have established a role for the canonical NF-κB pathway in innate and adaptive immune compartments, in both cell activation and development. Further animal studies are warranted to probe the functional specificity of individual NF-κB subunits in immune cells during actual immune responses to pathogens.

3.3 NF-κB dependent gene expression during immune response via the canonical pathway

The functional importance of the NF-κB system in immunity is underscored by an impressive list of genes that have been reported to contain functional κB-elements (www.nf-κB.org). These genes include a large number of inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, chemokines, their receptors and membrane bound proteases, as well as genes that can counteract apoptosis. More recent genetic studies, have established that the majority of TNF-induced gene activation events in MEF do indeed require NF-κB, and that different target genes have differential requirements for canonical NF-κB dimers, such as the RelA:p50 heterodimer vs. RelA:RelA homodimers, or cRel-containing dimers (Hoffmann et al., 2003). Furthermore, using a non-degradable form of IκB as a transgenic repressor of NF-κB function, large numbers of genes were shown to be expressed in an NF-κB-dependent manner in a variety of transformed cell lines.

However, in healthy, primary immune cells, it remains unclear how many genes are critically regulated by NF-κB, which dimers are involved and which of these target genes are responsible for physiological phenotypes in knockout mice. Interestingly, a recent study, revealed that in dendritic cells TLR4 induced expression of inflammatory or T-cell stimulatory genes require distinct RelA or cRel subunits (Wang et al., 2007), suggesting that there is a regulatory code for canonical NF-κB dimers that remains to be elucidated. Given the abundance of NF-κB (more than 100,000 molecules per cell), it may not be surprising that genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis revealed a large number of unexpected binding sites of unknown functional relevance (Martone et al., 2003; Schreiber et al., 2006). Therefore, such chromatin location studies must be coupled to functional analysis using genetic perturbations (knockouts and knock-in mutants) to elucidate the transcriptional regulatory code of NF-κB.

4. Immune organ development and the NF-κB/RelA:p50 dimer

4.1 Secondary lymphoid organ development via the LTβR

Secondary lymph nodes provide microenvironment for antigen recognition and lymphocyte maturation during an adaptive immune response. Lymph nodes are located throughout the body to monitor the draining fluids and migrating lymphocytes for pathological changes (Lo et al., 2006; Mebius, 2003). The ltbr-/- mice demonstrated that lymphotoxin-β receptor (LTβR) signaling critically regulates lymph node formation (Futterer et al., 1998; Rennert et al., 1998). During early embryogenesis, membrane bound LTα1β2 on the hematopoietically derived lymph tissue inducer cells (LTIC) signal through LTβR present on the stromal organizer cells to initiate lymph node development. LTβR engagement results in the production of organogenic chemokines, namely SLC, BLC and ELC, whose secretion allow further influx of LTIC, and cell adhesion molecules, such as ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, whose expression on stromal cells allow for adherence of LTIC through cell-surface integrins. Subsequent clustering between LTIC and stromal cells lead to the formation of secondary lymph nodes in the specific areas of the lymph node anlagen. Additionally, signaling through LTβR was shown to regulate spleen architecture, T/B cell segregation, germinal center formation and maintenance of lymph node microarchitecture in adult mice (Fu and Chaplin, 1999).

4.2 Requirement of RelA and p50 in the lymph node development

Beside its role in immune activation, the NF-κB RelA:p50 dimer has also been implicated in the immune development. Mice that lack RelA (combined with TNFR1 deficiency) revealed an early organogenic defect resulting in a complete lack of secondary lymph nodes in newborn mice. Analysis with radiation chimeras suggested a requirement for RelA within the non-hematopoietic stromal cells for the development of secondary lymphoid organs (Alcamo et al., 2002). Similarly, p50-deficient mice exhibited defects in lymphoid tissues with a loss of inguinal lymph nodes (Lo et al., 2006). A requirement of the RelA:p50 dimer in stromal cells for activating VCAM-1 or ICAM-1 gene expression during LTβR signaling (Dejardin et al., 2002; Lo et al., 2006) was proposed to be responsible for these lymph node phenotypes.

4.3 Mapping RelA:p50 dimer activation pathway downstream of LTβR

An LTβR agonist antibody, that functionally complements for the genetic deletion of LT-ligands in mice (Rennert et al., 1998), was used in a cell culture system to reveal RelA:p50 activation downstream of LTβR and for further analyzing the underlying activation mechanism (Basak et al., 2007). In contrast to TNFR, LTβR stimulation may not induce IKK2-complex activity or the degradation of the three canonical IκB proteins, IκBα, -β and -ε. Indeed, knockout MEF that lack all three canonical IκBs were shown to be defective in RelA:p50 activation in response to TNFR but not LTκR stimulation. As a result, the existence of an additional NF-κB inhibitor was proposed that regulates RelA:p50 activity during LTκR signaling.

Biochemical purification identified nfκb2/p100 as an additional RelA:p50-interacting protein. The precursor for the NF-κB protein p52, p100, possesses seven ankyrin repeats in its C-terminal inhibitory domain that was thought to keep it functionally inert. However, analyses of both recombinant and cellular p100 suggested that p100 can form a homodimer through its N-terminal RHR and utilizes the ARD of one polypeptide in an autoinhibitory conformation, but allows the ARD of the second polypeptide to associate with additional NF-κB dimers in trans (Fig. 2A). Such cytoplasmic (p100)2-inhibited complexes could be disrupted with deoxycholate liberating bound RelA:p50 DNA binding activity. As such, the “second ARD” of the asymmetric (p100)2 dimer was proposed to function as a fourth IκB, termed IκBδ (Basak et al., 2007).

Several developmental stimuli (e.g. LTαβ. BAFF, RANKL, CD40) have been described to activate a kinase cascade that includes the NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) and IKK1 and triggers stimulus-induced processing of p100 to p52 and nuclear accumulation of RelB-containing NF-κB dimers (Pomerantz and Baltimore, 2002; Senftleben et al., 2001; Xiao et al., 2004). This has been termed the “non-canonical” or the “alternative” NF-κB pathway. The new work (Basak et al., 2007) revealed that LTβR signaling induces degradation of IκBδ, resulting in the release of bound RelA:p50 into the nucleus but retaining the self-inhibited p100:p52 dimer in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A). Consistent to this proposal, nik-/- MEF displayed defects in NF-κB/RelA dependent gene expression during LTβR signaling (Yin et al., 2001). Similarly, signals transduced through CD40R and BAFFR that control B-cell maturation were also shown to utilize the NIK pathway for RelA activation (Ramakrishnan et al., 2004). The new model indicates a signaling axis that connects NIK and IKK1 with RelA:p50 activation during developmental signaling via stimulus-induced IκBδ degradation.

In sum, all NF-κB-inducing pathways activate RelA:p50 dimers from a latent cytoplasmic pool. Whereas the immune activation signals utilize the canonical NF-κB pathway and the three canonical IκB proteins IκBα, -β, -ε, immune developmental signals utilize the non-canonical pathways and IκBδ. NF-κB activation in response to developmental signals is weaker and delayed compared to inflammatory signals. The use of the smaller IκBδ bound pool, as opposed to the larger canonical IκB-bound pool, controls the amplitude of the RelA:p50 response during LTβR signaling. As differential thresholds of NF-κB activity may determine target gene expression, such amplitude modulation may therefore enable the expression of cell survival and cell adhesion molecules, without generating an inflammatory response during developmental processes.

5. Interconnected pathways for inflammatory and developmental signaling

5.1 A “four IκB” containing mathematical model

Unlike the three canonical IκBs, IκBδ is not degraded in response to IKK2 mediated inflammatory signals, but its expression is induced due to NF-κB dependent transcriptional activation of nfκb2/p100 (de Wit et al., 1998). To further address the relationship between canonical and non-canonical signaling, a set of ordinary differential equations, that describe synthesis, degradation and molecular interactions of p100, was included into a mathematical model that was already accounted for NF-κB activation dynamics in inflammatory settings (Hoffmann et al., 2002). The resulting model (Basak et al., 2007) included 98 biochemical reactions, which were parameterized based on biochemical measurements and parameter fitting algorithms. Simulation runs using this in silico model recapitulated IKK2-mediated degradation of classical IκBs during TNFR1 signaling as well as IKK1-mediated proteolysis of p100/IκBδ during LTβR signaling to predict NF-κB/RelA:p50 dimer activation dynamics in response to canonical or the non-canonical signals (Fig. 2B).

5.2 Crosstalk between the signaling mediated through TNFR1 and LTβR

Remarkably, simulations with the four IκB-containing mathematical model predicted that even a transient inflammatory exposure would have a lasting effect on the IκB homeostasis, such that the TNF-primed cells would display hyperactivation of RelA:p50 dimer during subsequent LTβR signaling, as compared to naïve cells (Basak et al., 2007). Indeed, biochemical experiments revealed an altered distribution of canonical and non-canonical IκB proteins, with an increased fraction of RelA:p50 dimer bound to IκBδ in TNF-primed cells. In TNF-primed cells, non-canonical signaling mediated through LTβR not only resulted in increased NF-κB activity, but also had qualitative effects on gene expression (Basak et al., 2007). Prominent RelA target genes, such as iκbα and tnf, that are not normally induced during LTβR signaling, were shown to be activated by the non-canonical pathway in TNF primed MEF. Therefore, inflammatory signaling appears to amplify developmental responses of NF-κB/RelA:p50 via a crosstalk mechanism that controls the cellular homeostasis of canonical and non-canonical IκB proteins.

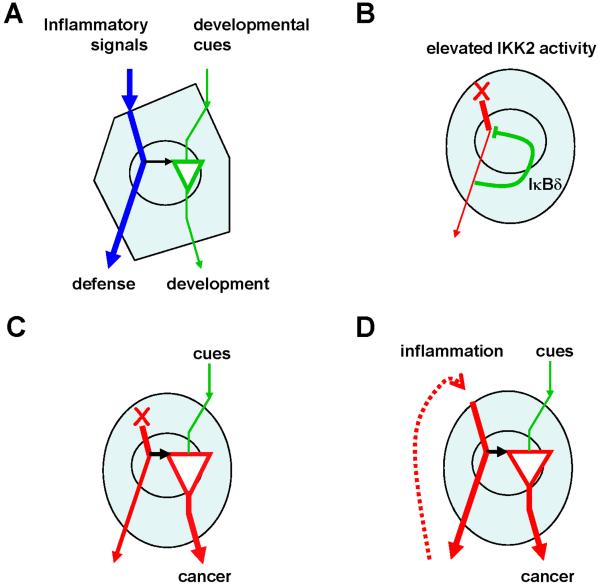

5.3 Implications of the signaling crosstalk in physiology

Within their physiological context, cells receive and process signals from a variety of extra-cellular cues. Therefore, the signaling crosstalk that modulates the amplitude of the NF-κB response during developmental processes may have profound physiological significance. Indeed, tnfr1-/- mice revealed developmental defects with a lack of Peyer's Patches and disrupted Marginal Zone formation (Neumann et al., 1996). In vitro generation of fibroblast reticular cells from lymph node tissue was shown to require both TNFR and LTβR signaling (Katakai et al., 2004), while in utero treatment of decoy receptors that abrogated TNFR or LTβR signaling or both revealed a cooperation between TNF/LT pathways that underlie lymph node biogenesis (Rennert et al., 1998). Also signaling through both LTβR and TNFR was shown to be required for dendritic cell development and expansion (Wang et al., 2005). Utilization of TNFR by LTα3 homotrimer ligand was thought to constitute a functional connection between the TNF and LT axes. The above-described model (Basak et al., 2007), instead, proposes a cell-autonomous signaling crosstalk mechanism via IκBδ to provide an alternative explanation for the requirement of inflammatory signaling in developmental pathways. In this proposal, inflammatory signaling regulates the strength of the non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway and thereby the cellular responsiveness to developmental cues (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. The signaling cross-talk model in physiology and in disease.

(A) A schematic representing normal healthy cells that receive both inflammatory (blue line) and developmental (green line) signals. Inflammatory stimuli, generally associated with pathogen responses, also boost developmental responses via signaling crosstalk within the NF-κB signaling system (black arrow). (B) A schematic representing a cancer cell with a cell-autonomous defect (red cross) that results in an elevated IKK activity. Such heightened IKK activity degrades theee canonical IκB isoforms, but IκBδ, whose expression is NF-κB inducible but whose degradation is IKK2-insensitive, provides a brake on chronic NF-κB activity. (C) Elevated IκBδ levels result in hyper-responsiveness of such cancerous cells to tonic developmental cues, that may contribute to pathological outcomes. (D) Elevated inflammation that is often associated with cancer may generate similar cellular hyper-responsiveness towards developmental cues via the signaling crosstalk, thus implicating a role of the developmental pathway in pathogenesis.

One might speculate that in other cases where such developmental cues may be persistently present or tonic, the canonical signaling pathway (initiated by transient inflammatory stimuli) may increase the cellular responsiveness to these tonic signals. Interestingly, it was proposed that inflammatory signaling co-operates with the non-canonical signaling mediated through Receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANK) to accelerate differentiation of the precursors into mature osteoclasts within bone marrow and in peripheral tissues (Walsh et al., 2006). Indeed, TNFα signaling, through TNFR1, enhanced osteoclast formation in vitro from the precursors that are pre-treated with RANKL (Yamashita et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2001). The significance of such crosstalk mechanisms in bone resorption and homeostasis, and in rheumatoid arthritis remains to be fully explored. Furthermore, how B-cell survival and proliferation program, mostly guided by the chronic signals mediated through BAFFR (and CD40R), is altered upon exposure to the transient inflammatory stimuli also remains to be investigated to fully understand the implications of the proposed signaling crosstalk between canonical and non-canonical signal transduction pathways.

5.4 Implication of the signaling crosstalk in disease

The homeostatically controlled distribution of canonical and non-canonical IκB proteins is also subject to disease-associated perturbations; such altered IκB homeostasis may be the underlying cause for pathological misregulation of NF-κB.

Chronically elevated nuclear NF-κB/RelA:p50 activity has long been associated with many different types of cancer, where it contributes to survival signaling, chemoresistance, proliferation and metastasis (Karin, 2006). Indeed, an elevated constitutive IKK2 activity has been observed in many different cancer cell-lines. With the newly appreciated role of IκBδ/(p100)2 as a fourth IκB that is not degraded in response to IKK2 signals, one might expect that IκBδ functions as an important brake to elevated canonical signaling (Fig. 3B). Indeed, in the absence of canonical IκB proteins, IκBδ limits NF-κB activity in MEF by sequestering an increased amount of RelA:p50 dimer in the cytoplasm (Basak et al., 2007). Similarly, samples derived from primary breast tumors and derived cell-lines revealed an elevated level of p100 protein that sequesters NF-κB dimers in the cytoplasm (Dejardin et al., 1995).

Further computational simulations predicted that such altered IκB homeostasis would also render cells hyper-responsive towards developmental stimuli, in that the degradation of IκBδ upon LTβR signaling resulted in a heightened RelA:p50 dimer activation (Basak et al., 2007). Experimental analyses demonstrated that LTβR stimulation in or MEF induced significantly more RelA:p50, as well as expression of inflammatory cytokines not normally induced in wild type cells by the same stimulus. Therefore, we suggest that disease-associated perturbations of the NF-κB system, which alter the strength of the non-canonical pathway, may turn the usually subtle cellular responses to weak, possibly tonic developmental signals into gene expression programs that contribute to pathologies (Fig. 3C).

There are some indications in the literature that altered responsiveness of disease-associated cells render normally benign developmental signals to have significant roles in pathology. For example, an inflammatory skin condition caused by keratinocyte-specific deletion of IκBα could be partially rescued not only by deletion of tnf or tnfr1, but also ltα, with only compound deficiency of tnf, ltα and ltβ completely rescuing this skin phenotype (Rebholz et al., 2007). Furthermore, a significant fraction of the malignant Reed Sternberg cells in Hodgkin lymphoma have been shown to harbor functionally defective iκbα gene (Krappmann et al., 1999). But more recently is was shown that signaling by BAFF is critical not only for promoting survival of these diseased cells, but also their growth and proliferation (Chiu et al., 2007). Finally, it is remarkable that components of the non-canonical pathway, such as LTβR, NIK, or NFκB2, are more often found to be mutated or misregulated in multiple myeloma than components of the canonical NF-κB pathway. Inhibition of this hyperactivated non-canonical pathway indeed led to growth arrest and cell death in vitro (Annunziata et al., 2007; Keats et al., 2007).

Inflammation has been identified as a tumor promoter, and the molecular link between them was identified as deregulated IKK2 and NF-κB activity (Greten et al., 2004). However, in cell culture, increased p100/IκBδ protein levels due to chronic inflammation severely attenuates the NF-κB response (Basak et al., 2007; Shih et al, 2008). Based on these observations, we propose that the non-canonical signaling pathway plays a critical role in controlling aberrant NF-κB activity associated with cancer cells (Fig. 3D). Non-canonical signaling could be the result of tonic developmental paracrine signals in situ, or an autocrine signaling loop acquired by the cancer cell. Therefore, we suggest that tonic developmental cytokines, could provide an opportunity for therapeutic intervention.

6. Towards an understanding of the multi-dimer NF-κB Signaling System

6.1 Non-canonical activation of NF-κB/RelB DNA binding acitvity

Non-canonical signaling results not only in RelA:p50 activation, but there is a significant literature on the activation of the RelB:p52 dimer, which may be slower and more persistent. LTβR stimulation was shown to induce nuclear accumulation of RelB:p52 via the NIK/IKK1 pathway and the phosphorylation and processing of de novo synthesized, rather than pre-existing p100 protein (Mordmuller et al., 2003; Senftleben et al., 2001; Xiao et al., 2001). Indeed, a first phase of RelA activity was proposed to induce p100 synthesis to amplify RelB:p52 dimer activation (Dejardin et al., 2002; Muller and Siebenlist, 2003), but recent evidence indicates that RelA-responsive expression of RelB is more important in this regard (Basak et al., 2008). Signaling through multiple other TNF receptor superfamily members, such as BAFFR, CD40R, BCMA, TAC1 or RANK, was also reported to activate the RelB:p52 dimer via the non-canonical pathway.

Indeed, genetic analysis indicated that RelB plays an essential role in lymph node development, especially in maintaining lymph node architecture in adult mice (Weih et al., 2001; Yilmaz et al., 2003). Important lymphoid chemokine genes, such as BLC and SLC, were shown to be RelB target genes (Basak et al., 2008; Schneider et al., 2004) via a proposed variant kappaB site that recruits RelB- but not RelA-containing dimers upon LTβR stimulation (Bonizzi et al., 2004). Homozygous knockin mice expressing a non-activatable IKK1 variant (ikk1AA/AA) show impaired lymphoid organogenesis (Senftleben et al., 2001) due to stromal cell defects (Bonizzi et al., 2004). These studies established that the non-canonical pathway plays a critical role in development of lymphoid tissues. However, genome-wide analysis to identify RelB target genes downstream of LTβR is wanting and bears the promise to define the promoter code for RelA and RelB containing NF-κB dimers.

6.2 Disparate lymph node phenotype in various NF-κB knockouts

The straight forward model that describes the canonical signaling as controlling inflammation and the non-canonical signaling as controlling secondary lymphoid tissue development is, however, not well supported by mouse knockout studies. For example, nfkb2-/-mice, which are deficient in the primary regulators of non-canonical NF-κB signaling p100/p52, display defects only in the inguinal lymph node formation with all other nodes present at wild type frequencies (Lo et al., 2006). It was proposed that the RelB:p50 dimer may be responsible for the incomplete penetrance of phenotype in nfkb2-/- mice. Indeed, nfkb1-/-nfkb2-/- double knockout mice displayed complete lack of lymph nodes, thus phenocopying LTβR deficient mice (Lo et al., 2006). Interestingly, nfkb1-/- mice were also shown to have inguinal lymph node defects and derived MEF showed attenuated RelB activation in response to LTβR stimulation (Lo et al., 2006). As described earlier, rela-/- mice also exhibited an early organogenic defect with complete absence of lymph nodes in new born mice (Alcamo et al., 2002), and RelB:p52 dimer activation by LTβR signaling was shown to be defective in rela-/- MEF (Basak et al., 2008). As opposed to the commonly held view of distinct canonical and non-canonical signaling axes, these studies indicated the potential involvement of multiple cross-regulatory mechanisms, whose details may best be presented and characterized within network description of the NF-κB signaling system.

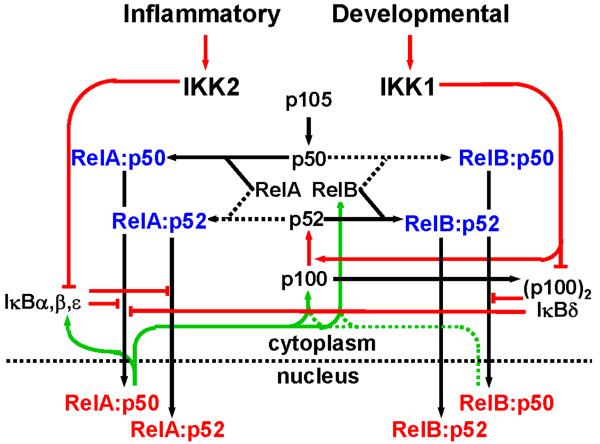

6.3 A multi-NF-κB dimer signaling system

We have recently explored the functional interconnectedness of these two pathways by systematically characterizing the mechanisms that control the generation of each of the relevant NF-κB dimers and thereby determine their availability for stimulus-responsive activation (Basak et al., 2008). The interdependencies between the components of the NF-κB signaling system could be represented using a wiring diagram (Fig. 4). Here, the preferred biochemical reactions have been indicated with a solid line, lesser reactions with a dashed line. Feedback reactions are denoted with a green line, constitutive and inducible processes with black and red lines, respectively.

Fig. 4. A wiring diagram to depict functional relationships between various components within the NF-κB signaling system.

NF-κB monomers are shown in black, cytoplasmic dimers in blue and nuclear dimers in red. Constitutive processes are shown in black lines, regulated processes in red and feedback processes in green. Preferred biochemical reactions are shown in solid lines, while lesser reactions in dashed line. The wiring accounts for the generation and activation of four NF-κB dimers that are detected in response to LTβR signaling, namely RelA:p50, RelA:p52, RelB:p50 and RelB:p52 dimers. The NF-κB signaling system receives signals from both inflammatory and developmental cues through IKK2 and IKK1 kinases, respectively, to activate distinct NF-κB dimers during inflammation or during development. See the text for a detailed description.

The model shows that inflammatory signals activate RelA:p50 dimer through IKK2 mediated IκB degradation, while IκBδ/(p100)2-inhibited RelA:p50 and RelB:p50 complexes are released into the nucleus upon IKK1 mediated developmental signaling. Furthermore, p52 is cotranslationally generated from p100 in response to IKK1 signaling (Mordmuller et al., 2003) and dimerizes with RelB and RelA to appear as RelB:p52 and RelA:p52 DNA binding complexes. The RelA:p50 dimer controls RelB synthesis and thus modulates stimulus responsive activation of the RelB dimers via the non-canonical pathway. On the other hand, feedback inhibition mediated by the re-synthesized IκBs are capable of terminating RelA responses. In addition, it was shown that the RelB-containing dimers could upregulate NFκB2 and RelB mRNA synthesis (Basak et al., 2008), forming a positive feedback loop in the pathway. Finally, p50 and p52 compete with each other for binding to a limited pool of RelA and RelB proteins. Constitutive p105 processing generates p50 in the resting cell. In contrast, p100 is stabilized by RelB (A. Fusco and G. Ghosh, UCSD) but its processing to p52 is responsive to developmental stimuli such as LT.

6.4 Perturbations in the NF-κB signaling system via gene knockouts

Studies of single and compound NF-κB gene deletions resulted in unexpected mouse phenotypes and perturbed RelB:p52 dimer activation by LTβR signaling (Basak et al., 2008; Lo et al., 2006). Analysis of the proposed model as depicted in the system-wiring diagram in Fig. 4, not only assists in understanding the molecular basis of these knockout phenotypes but also confirms the existence of multiple cross-regulatory mechanisms as emergent systems properties.

First, the lack of RelA activity not only resulted in the complete absence of NF-κB activity during inflammatory signaling but also abrogated the non-canonical pathway. Two distinct mechanisms emerge when analyzing the proposed NF-κB signaling system model to account for such defective RelB activation. First, RelA deficiency reduces RelB (and also p100) mRNA synthesis. Second, excess p50 monomer (resulting from the lack of RelA) competes with p52 for RelB binding and thus interferes with p52 generation and RelB:p52 dimer formation. Indeed, in cell culture, RelA-deficiency was shown to result in a reduced level of RelB mRNA and protein, and also p52 generation by LTβR signaling was shown to be abrogated in rela-/-MEF but was rescued in rela-/-nfkb1-/- MEF (Basak et al., 2008).

It has been suggested that RelB binding to p100 inhibits its stimulus-responsive processing (A. Fusco and G. Ghosh, UCSD), whereas, RelA-bound p100 is subjected to constitutive processing (Basak et al., 2008). The wiring diagram indicates that in the absence of its preferred interaction partner p50, RelA would compete with RelB to bind p100. RelA binding would then allow for an increased accumulation of p52 through constitutive p100 processing. Indeed, elevated p100 processing into p52 was observed in nfkb1-/- MEF (Basak et al., 2008) that resulted in functional compensation at the level of κB-DNA binding activity and gene expression in response to TNF stimulation (Hoffmann et al., 2003). However, elevated processing also depletes the cellular pool of p100 that can be inducibly processed into p52 during non-canonical signaling. As such, functional compensation in inflammatory signaling impairs the systems responsiveness to developmental signals. Therefore, the system wiring diagram illustrates an explanation for the observed NF-κB activation defect in nfkb1-/- MEF that may impair lymph node development in nfkb1-/- mice (Lo et al., 2006). In concordance to the competition hypothesis, elevated constitutive p100 processing was reduced to normal levels in rela-/-nfkb1-/- MEF (Basak et al., 2008).

Similarly, the wiring diagram illustrates that in nfkb2-/- MEF, the majority of the RelB protein is available to bind p50. As RelB:p50 is not subject to efficient inhibition by IκB proteins, it appears as a constitutive DNA binding activity in the nucleus. We postulate that the transcriptional activity of the constitutive RelB:p50 dimer (Basak et al., 2008) partly masks a phenotype that is otherwise expected in nfkb2-/- mice (Lo et al., 2006).

In sum, genetic and biochemical analyses indicated that the lymph node development and its maintenance requires both components of the canonical (rela and nfkb1) and the non-canonical pathway (relb and nfkb2). Understanding LTβR signaling requires integration of both pathways into a single NF-κB signaling system, which describes the generation of a number of NF-κB dimers and their interactions with IκB proteins. Regulation of the homeostasis of dimer availability emerged as an important theme in understanding NF-κB activation during LTβR signaling. Hence, the system wiring diagram not only emphasized the functional interdependence of the canonical and the non-canonical pathways, but the functional relationships between homeostatic mechanisms that are responsible for NF-κB dimer generation and the stimulus-induced, dynamic mechanisms that control dimer activation.

7. Concluding Remarks

As mouse genetic studies of signaling proteins have yielded surprising phenotypes and thus revealed unexpected functional interdependencies and redundancies, we are forced to confront the interconnectedness of a signaling network that breaks the simplifying assumptions of linear signaling pathways. With a large number of TNFR superfamily members functionally interacting with a complex NF-κB signaling system consisting of 15 possible dimers, a systems biology approach may be called for in addressing questions of signaling specificity and crosstalk. Within this context, mathematical modeling of the signaling system allows for quantitative predictions and motivates a quantitative biochemical and biophysical analysis of protein interactions and kinetic reactions.

Given the importance of the NF-κB signaling system in physiology and disease, further studies that address the specificity of RelA and RelB-mediated gene expression programs, signaling crosstalk in both physiological and pathological contexts, and alternate homeostatic signaling states during cell differentiation, and in cancer-associated perturbations will be of great interest. Quantitative computational modeling may be a useful tool to complement systematic experimental studies, and may lead to novel therapeutic strategies that minimize non-specific or off-target side effects.

8. Acknowledgements

In the interest of clarity, we have narrowly focused this review article and apologize for not citing many important contributions in the field. Research on related topics in the Signaling Systems Laboratory was funded by the NIH. We also acknowledge helpful discussions with members of the laboratory during preparation of the manuscript.

Biographies

Soumen Basak is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the Signaling Systems Laboratory, UCSD. His research interests encompass the functional interactions between different stimuli within the immune system, and how these are mediated through the NF-κB signaling system. Signaling crosstalk is a systems emergent property that can be characterized with interdisciplinary tools, involving biochemistry, genetics and mathematical modeling. He received his graduate training with Dhrubajyoti Chattopadhdyay (Calcutta University) on the molecular mechanisms that regulate Chandipura virus replication and gene expression.

Alexander Hoffmann is Assistant Professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at UCSD. He established the Signaling Systems Laboratory (http://signalingsystems.ucsd.edu) at UCSD in 2003 to study signaling networks with a combination of biochemical, genetic and computational modeling tools. A primary focus is the NF-κB pathway that controls diverse gene expression programs. His graduate training was with Robert G Roeder (Rockefeller University) on the molecular characterization of TFIID and post-doctoral training was with David Baltimore (MIT and Caltech) on the genetic analysis of NF-κB. He is a Hellman Foundation fellow, and an Ellison Foundation Investigator in Aging Research.

References

- Alcamo E, Hacohen N, Schulte LC, Rennert PD, Hynes RO, Baltimore D. Requirement for the NF-kappaB family member RelA in the development of secondary lymphoid organs. J Exp Med. 2002;195:233–244. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcamo E, Mizgerd JP, Horwitz BH, Bronson R, Beg AA, Scott M, Doerschuk CM, Hynes RO, Baltimore D. Targeted mutation of TNF receptor I rescues the RelA-deficient mouse and reveals a critical role for NF-kappa B in leukocyte recruitment. J Immunol. 2001;167:1592–1600. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziata CM, Davis RE, Demchenko Y, Bellamy W, Gabrea A, Zhan F, Lenz G, Hanamura I, Wright G, Xiao W, Dave S, Hurt EM, Tan B, Zhao H, Stephens O, Santra M, Williams DR, Dang L, Barlogie B, Shaughnessy JD, Jr., Kuehl WM, Staudt LM. Frequent engagement of the classical and alternative NF-kappaB pathways by diverse genetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. Activation of DNA-binding activity in an apparently cytoplasmic precursor of the NF-kappa B transcription factor. Cell. 1988a;53:211–217. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. I kappa B: a specific inhibitor of the NF-kappa B transcription factor. Science. 1988b;242:540–546. doi: 10.1126/science.3140380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak S, Kim H, Kearns JD, Tergaonkar V, O'Dea E, Werner SL, Benedict CA, Ware CF, Ghosh G, Verma IM, Hoffmann A. A fourth IkappaB protein within the NF-kappaB signaling module. Cell. 2007;128:369–381. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak S, Shih VF-S, Hoffmann A. Generation and activation of multiple dimeric transcription factors within the NF-B signaling system. MCB accepted. 2008 doi: 10.1128/MCB.01469-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg AA, Sha WC, Bronson RT, Ghosh S, Baltimore D. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-kappa B. Nature. 1995;376:167–170. doi: 10.1038/376167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonizzi G, Bebien M, Otero DC, Johnson-Vroom KE, Cao Y, Vu D, Jegga AG, Aronow BJ, Ghosh G, Rickert RC, Karin M. Activation of IKKalpha target genes depends on recognition of specific kappaB binding sites by RelB:p52 dimers. Embo J. 2004;23:4202–4210. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothby MR, Mora AL, Scherer DC, Brockman JA, Ballard DW. Perturbation of the T lymphocyte lineage in transgenic mice expressing a constitutive repressor of nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1897–1907. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.11.1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu A, Xu W, He B, Dillon SR, Gross JA, Sievers E, Qiao X, Santini P, Hyjek E, Lee JW, Cesarman E, Chadburn A, Knowles DM, Cerutti A. Hodgkin lymphoma cells express TACI and BCMA receptors and generate survival and proliferation signals in response to BAFF and APRIL. Blood. 2007;109:729–739. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covert MW, Leung TH, Gaston JE, Baltimore D. Achieving stability of lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-kappaB activation. Science. 2005;309:1854–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.1112304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Dokter WH, Koopmans SB, Lummen C, van der Leij M, Smit JW, Vellenga E. Regulation of p100 (NFKB2) expression in human monocytes in response to inflammatory mediators and lymphokines. Leukemia. 1998;12:363–370. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejardin E, Bonizzi G, Bellahcene A, Castronovo V, Merville MP, Bours V. Highly-expressed p100/p52 (NFKB2) sequesters other NF-kappa B-related proteins in the cytoplasm of human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 1995;11:1835–1841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejardin E, Droin NM, Delhase M, Haas E, Cao Y, Makris C, Li ZW, Karin M, Ware CF, Green DR. The lymphotoxin-beta receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF-kappaB pathways. Immunity. 2002;17:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDonato JA, Mercurio F, Karin M. Phosphorylation of I kappa B alpha precedes but is not sufficient for its dissociation from NF-kappa B. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1302–1311. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu YX, Chaplin DD. Development and maturation of secondary lymphoid tissues. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:399–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futterer A, Mink K, Luz A, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Pfeffer K. The lymphotoxin beta receptor controls organogenesis and affinity maturation in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Immunity. 1998;9:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S81–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, Park JM, Li ZW, Egan LJ, Kagnoff MF, Karin M. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitisassociated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann A, Baltimore D. Circuitry of nuclear factor kappaB signaling. Immunol Rev. 2006;210:171–186. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann A, Leung TH, Baltimore D. Genetic analysis of NF-kappaB/Rel transcription factors defines functional specificities. Embo J. 2003;22:5530–5539. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann A, Levchenko A, Scott ML, Baltimore D. The IkappaB-NF-kappaB signaling module: temporal control and selective gene activation. Science. 2002;298:1241–1245. doi: 10.1126/science.1071914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxford T, Huang DB, Malek S, Ghosh G. The crystal structure of the IkappaBalpha/NF-kappaB complex reveals mechanisms of NF-kappaB inactivation. Cell. 1998;95:759–770. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441:431–436. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katakai T, Hara T, Sugai M, Gonda H, Shimizu A. Lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells construct the stromal reticulum via contact with lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2004;200:783–795. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns JD, Basak S, Werner SL, Huang CS, Hoffmann A. IkappaBepsilon provides negative feedback to control NF-kappaB oscillations, signaling dynamics, and inflammatory gene expression. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:659–664. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keats JJ, Fonseca R, Chesi M, Schop R, Baker A, Chng WJ, Van Wier S, Tiedemann R, Shi CX, Sebag M, Braggio E, Henry T, Zhu YX, Fogle H, Price-Troska T, Ahmann G, Mancini C, Brents LA, Kumar S, Greipp P, Dispenzieri A, Bryant B, Mulligan G, Bruhn L, Barrett M, Valdez R, Trent J, Stewart AK, Carpten J, Bergsagel PL. Promiscuous mutations activate the noncanonical NF-kappaB pathway in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontgen F, Grumont RJ, Strasser A, Metcalf D, Li R, Tarlinton D, Gerondakis S. Mice lacking the c-rel proto-oncogene exhibit defects in lymphocyte proliferation, humoral immunity, and interleukin-2 expression. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1965–1977. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.16.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krappmann D, Emmerich F, Kordes U, Scharschmidt E, Dorken B, Scheidereit C. Molecular mechanisms of constitutive NF-kappaB/Rel activation in Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:943–953. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Nabel GJ. A new member of the I kappaB protein family, I kappaB epsilon, inhibits RelA (p65)-mediated NF-kappaB transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6184–6190. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo JC, Basak S, James ES, Quiambo RS, Kinsella MC, Alegre ML, Weih F, Franzoso G, Hoffmann A, Fu YX. Coordination between NF-kappaB family members p50 and p52 is essential for mediating LTbetaR signals in the development and organization of secondary lymphoid tissues. Blood. 2006;107:1048–1055. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martone R, Euskirchen G, Bertone P, Hartman S, Royce TE, Luscombe NM, Rinn JL, Nelson FK, Miller P, Gerstein M, Weissman S, Snyder M. Distribution of NF-kappaB-binding sites across human chromosome 22. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12247–12252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135255100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mebius R. Otrganogenesis of lymphoid tissues. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:292–303. doi: 10.1038/nri1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordmuller B, Krappmann D, Esen M, Wegener E, Scheidereit C. Lymphotoxin and lipopolysaccharide induce NF-kappaB-p52 generation by a co-translational mechanism. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:82–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller JR, Siebenlist U. Lymphotoxin beta receptor induces sequential activation of distinct NF-kappa B factors via separate signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12006–12012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann B, Luz A, Pfeffer K, Holzmann B. Defective Peyer's patch organogenesis in mice lacking the 55-kD receptor for tumor necrosis factor. J Exp Med. 1996;184:259–264. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M, Naumann M. Beyond IkappaBs: alternative regulation of NF-kappaB activity. Faseb J. 2007;21:2642–2654. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7615rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouaaz F, Arron J, Zheng Y, Choi Y, Beg AA. Dendritic cell development and survival require distinct NF-kappaB subunits. Immunity. 2002;16:257–270. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz JL, Baltimore D. Two pathways to NF-kappaB. Mol Cell. 2002;10:693–695. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00697-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan P, Wang W, Wallach D. Receptor-specific signaling for both the alternative and the canonical NF-kappaB activation pathways by NF-kappaB-inducing kinase. Immunity. 2004;21:477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebholz B, Haase I, Eckelt B, Paxian S, Flaig MJ, Ghoreschi K, Nedospasov SA, Mailhammer R, Debey-Pascher S, Schultze JL, Weindl G, Forster I, Huss R, Stratis A, Ruzicka T, Rocken M, Pfeffer K, Schmid RM, Rupec RA. Crosstalk between keratinocytes and adaptive immune cells in an IkappaBalpha protein-mediated inflammatory disease of the skin. Immunity. 2007;27:296–307. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennert PD, James D, Mackay F, Browning JL, Hochman PS. Lymph node genesis is induced by signaling through the lymphotoxin beta receptor. Immunity. 1998;9:71–79. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80589-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidereit C. IkappaB kinase complexes: gateways to NF-kappaB activation and transcription. Oncogene. 2006;25:6685–6705. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider K, Potter KG, Ware CF. Lymphotoxin and LIGHT signaling pathways and target genes. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:49–66. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber J, Jenner RG, Murray HL, Gerber GK, Gifford DK, Young RA. Coordinated binding of NF-kappaB family members in the response of human cells to lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5899–5904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510996103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senftleben U, Cao Y, Xiao G, Greten FR, Krahn G, Bonizzi G, Chen Y, Hu Y, Fong A, Sun SC, Karin M. Activation by IKKalpha of a second, evolutionary conserved, NF-kappa B signaling pathway. Science. 2001;293:1495–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.1062677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha WC, Liou HC, Tuomanen EI, Baltimore D. Targeted disruption of the p50 subunit of NF-kappa B leads to multifocal defects in immune responses. Cell. 1995;80:321–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih, et al. 2008. i.p. in preparation.

- Walsh MC, Kim N, Kadono Y, Rho J, Lee SY, Lorenzo J, Choi Y. Osteoimmunology: interplay between the immune system and bone metabolism. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:33–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang X, Hussain S, Zheng Y, Sanjabi S, Ouaaz F, Beg AA. Distinct roles of different NF-kappa B subunits in regulating inflammatory and T cell stimulatory gene expression in dendritic cell. J Immunol. 2007;178:6777–6788. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YG, Kim KD, Wang J, Yu P, Fu YX. Stimulating lymphotoxin beta receptor on the dendritic cells is critical for their homeostasis and expansion. J Immunol. 2005;175:6997–7002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weih DS, Yilmaz ZB, Weih F. Essential role of RelB in germinal center and marginal zone formation and proper expression of homing chemokines. J Immunol. 2001;167:1909–1919. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner SL, Barken D, Hoffmann A. Stimulus specificity of gene expression programs determined by temporal control of IKK activity. Science. 2005;309:1857–1861. doi: 10.1126/science.1113319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside ST, Epinat JC, Rice NR, Israel A. I kappa B epsilon, a novel member of the I kappa B family, controls RelA and cRel NF-kappa B activity. Embo J. 1997;16:1413–1426. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G, Fong A, Sun SC. Induction of p100 processing by NF-kappaB-inducing kinase involves docking IkappaB kinase alpha (IKKalpha) to p100 and IKKalpha-mediated phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30099–30105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401428200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G, Harhaj EW, Sun SC. NF-kappaB-inducing kinase regulates the processing of NF-kappaB2 p100. Mol Cell. 2001;7:401–409. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T, Yao Z, Li F, Zhang Q, Badell IR, Schwarz EM, Takeshita S, Wagner EF, Noda M, Matsuo K, Xing L, Boyce BF. NF-kappaB p50 and p52 regulate receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL) and tumor necrosis factor-induced osteoclast precursor differentiation by activating c-Fos and NFATc1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18245–18253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz ZB, Weih DS, Sivakumar V, Weih F. RelB is required for Peyer's patch development: differential regulation of p52-RelB by lymphotoxin and TNF. Embo J. 2003;22:121–130. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Wu L, Wesche H, Arthur CD, White JM, Goeddel DV, Schreiber RD. Defective lymphotoxin-beta receptor-induced NF-kappaB transcriptional activity in NIK-deficient mice. Science. 2001;291:2162–2165. doi: 10.1126/science.1058453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel U, Baeuerle PA. Purified human I kappa B can rapidly dissociate the complex of the NF-kappa B transcription factor with its cognate DNA. Cell. 1990;61:255–265. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90806-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YH, Heulsmann A, Tondravi MM, Mukherjee A, Abu-Amer Y. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) stimulates RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis via coupling of TNF type 1 receptor and RANK signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:563–568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Vig M, Lyons J, Van Parijs L, Beg AA. Combined deficiency of p50 and cRel in CD4+ T cells reveals an essential requirement for nuclear factor kappaB in regulating mature T cell survival and in vivo function. J Exp Med. 2003;197:861–874. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]