Abstract

AIMS

To investigate whether, in patients in whom drug–drug interaction (DDI) alerts on QTc prolongation were overridden, the physician had requested an electrocardiogram (ECG), and if these ECGs showed clinically relevant QTc prolongation.

METHODS

For all patients with overridden DDI alerts on QTc prolongation during 6 months, data on risk factors for QT prolongation, drug class and ECGs were collected from the medical record. Patients with ventricular pacemakers, patients treated on an outpatient basis, and patients using the low-risk combination of cotrimoxazole and tacrolimus were excluded. The magnitude of the effect on the QTc interval was calculated if ECGs before and after overriding were available. Changes of the QTc interval in these cases were compared with those of a control group using one QTc-prolonging drug.

RESULTS

In 33% of all patients with overridden QTc alerts an ECG was recorded within 1 month. ECGs were more often recorded in patients with more risk factors for QTc prolongation and with more QTc overrides. ECGs before and after the QTc override were available in 29% of patients. Thirty-one percent of patients in this group showed clinically relevant QTc prolongation with increased risk of torsades de pointes or ventricular arrhythmias. The average change in QTc interval was +31 ms for cases and −4 ms for controls.

CONCLUSIONS

Overriding the high-level DDI alerts on QTc prolongation rarely resulted in the preferred approach to subsequently record an ECG. If ECGs were recorded before and after QTc overrides, clinically relevant QTc prolongation was found in one-third of cases. ECG recording after overriding QTc alerts should be encouraged to prevent adverse events.

Keywords: alert override, drug therapy, computer assisted, computerized physician order entry, error management, patient safety, QTc-prolongation

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT.

A large number of drugs can prolong the QTc interval on the electrocardiogram (ECG).

Clinical decision support systems may generate drug safety alerts on QTc prolongation.

Drug safety alerts are frequently overridden.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

QTc alert overriding does rarely result in ECG recordings.

ECGs before and after QTc overrides reveal clinically relevant QTc prolongation.

Introduction

Many cardiac and noncardiac drugs have effects on cardiac repolarization and can prolong the QTc interval on the electrocardiogram (ECG). The use of these drugs is associated with an increased risk of serious ventricular arrhythmias [e.g. torsades de pointes (TdP)] and sudden cardiac death [1–10]. The QTc interval can be used as a surrogate marker for the prediction of sudden cardiac death. Although this relationship is indirect [2, 3], prolongation of the absolute QTc interval beyond 500 ms and/or an increase of >60 ms is regarded as indicative of an increased risk of TdP [1, 2, 6, 10]. Many studies investigated the effects and risks of the use of a single QTc-prolonging drug [2, 3, 8, 9]. However, hardly any literature is available on the risks of TdP if two or more QTc-prolonging drugs are combined.

Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems with integrated computerized clinical decision support often generate drug–drug interaction (DDI) alerts on QTc prolongation. These alerts are frequently overridden, and it is not clear how often an ECG showing acceptable QTc intervals justifies this overriding. The aim of this study was to investigate whether overridden DDI alerts on QTc prolongation result in ECG recording and in how many instances this reveals clinically relevant QTc prolongation.

The questions to be answered were:

How often do overridden DDI alerts on QTc prolongation result in ECG recording following the prescription?

Are there any differences in risk factors, alert numbers or ward type between patients with and without ECG recordings?

Which drug combinations do result in clinical relevant QTc prolongation and risk of TdP?

Is QTc prolongation after addition of QT-prolonging drug(s) more pronounced than upon continuation of one QT-prolonging drug?

Background

The QT interval on the surface ECG is measured from the beginning of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave and varies with heart rate. Therefore, the QT interval is generally corrected for heart rate, resulting in the QTc interval. Bazett's formula, which is often used for the calculation of the QTc interval, divides the QT interval by the square root of the RR interval (QTc = QT/√RR). Besides congenital long QT syndrome, many noncongenital factors may predispose to QT prolongation and higher risk of TdP, such as older age, female gender, cardiovascular disease (left ventricular hypertrophy, low left ventricular ejection fraction, ischaemia), bradycardia and electrolyte disturbances (hypokalaemia and hypomagnesaemia) [6]. Furthermore, several drugs may result in QTc prolongation by blocking potassium currents and/or by pharmacokinetically increasing serum levels of these drugs by DDIs reducing cytochrome P450 activity. Higher doses and renal failure may also result in higher serum levels of these drugs and consequently in QTc prolongation [6].

QTc prolongation may predispose to ventricular arrhythmias, which may be fatal, but a linear relationship between QTc prolongation and risk of TdP is absent. However, a patient with a QTc interval >500 ms is regarded as at risk for TdP [2]. Of patients with TdP on QTc-prolonging drugs, 5–10% appear to have a subclinical form of the long QT syndrome [2], but for the majority of patients with TdP this is not the case. The relationship between potassium current blocking effect and TdP is not clear-cut either. Amiodarone blocks potassium currents and often prolongs the QT interval beyond 500 ms, but rarely causes TdP [2].

The G-standard is the Dutch national drug database and contains drug (safety) information for all drugs registered in the Netherlands, including DDIs [11]. All CPOEs in the Netherlands make use of this G-standard, which has included DDI alerts on QTc prolongation since March 2005. All drugs with clinical evidence of TdP (lists D and E of De Ponti [3, 7]) were generating this alert, as well as all class Ia and III antiarrhythmics. The standardized alert text from the G-standard for DDIs on QTc prolongation is very long and consists of a summary of the effects of the combination, a recommendation about what to do, risk factors for a prolonged QTc interval, the mechanism of the DDI, clinical effects, values for normal QT intervals, and the drugs that generate the alert.

The website http://www.torsades.org of the University of Arizona distinguishes between drugs that are known for causing TdP (class 1), drugs with probable risk of causing TdP (class 2) and drugs that are unlikely to cause TdP (class 4).

Methods

Setting

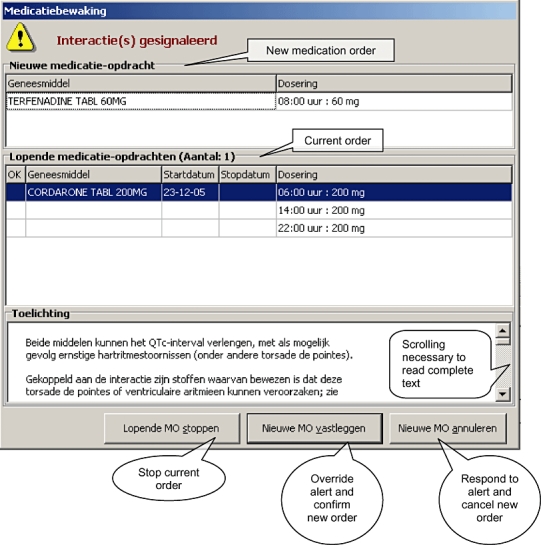

This study was conducted at the 1237-bed Erasmus University Medical Centre (Rotterdam, the Netherlands). All non-intensive care unit wards use the CPOE Medicatie/EVS® (Leiden, the Netherlands), which generates drug safety alerts for DDIs, overdose, and duplicate orders that are presented intrusively (Figure 1). Overridden drug safety alerts are routinely logged for pharmacy review.

Figure 1.

Example of a drug–drug interaction alert on QTc prolongation. The complete text can only be read if it is scrolled down. The translated text seen at a glance is: ‘Both drugs may prolong the QTc-interval and may possibly result in serious arrhythmias (torsades de pointes among others). Drugs known for their potential to cause ventricular arrhythmias are linked to this drug-drug interaction; see …’

Study population

All patients with overridden DDI alerts on QTc prolongation in Medicatie/EVS® version 2.20 between 1 February 2006 and 31 July 2006 in the Centre Location of Erasmus MC were selected. Patients with ventricular pacemakers or treated on an outpatient basis were excluded, as were patients treated with the low-risk combination of tacrolimus with prophylactic, low dose cotrimoxazole (class 2 and 4 on http://www.torsades.org). Patients on long-term use of QTc-prolonging drugs with unknown start date or no longer using the combination of QTc-prolonging drugs were also excluded. For each patient in the cohort a sex- and age-matched control with two ECG recordings during use of one QTc-prolonging drug was selected in the same time frame to evaluate within-patient variability.

Data analysis

For each patient included, the interacting drugs, risk factors for TdP and digital ECG recordings (12-lead resting ECGs recorded with a Mortara electrocardiograph) were collected. Risk factors for TdP were defined as: female gender, age > 65 years, presence of cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, cerebrovascular accident, peripheral atherosclerotic vasculopathy), diabetes mellitus (use of glucose-lowering drugs) or renal failure (glomerular filtration rate < 50 ml min−1) and potassium level < 3.5 mmol l−1. Drugs were categorized using the classification of http://www.torsades.org. The QTc intervals were defined as prolonged if >470 ms for women and >450 ms for men. Increased risk of TdP was defined as QTc interval >500 ms or an increase of the QTc interval >60 ms upon addition of at least one QTc-prolonging drug. Statistical comparisons were performed with Student's t-test (for independent samples) and χ2 test in SPSS version 10.1 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

In the 6-month study period, DDI alerts on QTc prolongation were overridden in 368 patients; 200 patients were excluded for different reasons (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient selection

| Patients with drug safety alerts on QTc prolongation from 1 February to 31 July 2006 | 368 | |

| Patients excluded | 200 | |

| Treated on an outpatient basis | 35 | |

| Using tacrolimus and low-dose cotrimoxazole | 124 | |

| Combination already discontinued | 22 | |

| Long-term use of combination (start date unknown) | 7 | |

| Ventricular pacemaker | 4 | |

| Other reasons | 8 | |

| Patients included | 168 | |

The inclusion criteria were met in 168 patients, and Table 2 shows the patient characteristics. For these 168 patients, 483 alerts were overridden with 70 different drug combinations. The majority of overridden alerts (91%) were due to at least one drug with a high risk of causing TdP (class 1). In 93% of the patients, besides the medication, there was at least one additional risk factor for TdP.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics cohort

| Cohort (n= 168) | |

|---|---|

| Female gender | 73 (44%) |

| Age > 65 years | 87 (52%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 118 (70%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 43 (26%) |

| Renal failure (GFR < 50 ml min−1)* | 43 (30%) |

| Potassium level < 3.5 mmol l−1† | 10 (6.9%) |

| Average number of risk factors | 2.2 ± 1.2 |

| CI −0.2, 4.6 | |

| Average number of QTc-prolonging drugs | 2.2 ± 0.4 |

| CI 1.4, 2.9 | |

| Two QTc-prolonging drugs | 139 (83%) |

| Three QTc-prolonging drugs | 29 (17%) |

| No ECG | 24 (14%) |

| ECG only before DDI | 88 (52%) |

| ECG only after DDI | 7 (4.2%) |

| ECG before and after DDI | 49 (29%) |

| ECG after DDI within 1 week‡ | 42 (75%) |

| Pharmacists' advise to make an ECG‡ | 8 (14%) |

Calculated on all patients in whom an estimated GFR was available (141).

Calculated on all patients with a measured potassium level (145).

Calculated on all patients with an ECG after DDI overriding (56). CI, 95% confidence interval; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; DDI, drug–drug interaction.

In 56 patients (33%) an ECG was made within 1 month after overriding the DDI alert and in 42 patients (25%) within 1 week of the prescription.

Differences between patients with and without an ECG being recorded are presented in Table 3. ECGs were more often recorded in patients suffering from cardiovascular disease and in patients with a higher average number of risk factors and overridden alerts. On cardiology wards, in 45% of patients with overridden DDIs an ECG was recorded, whereas this occurred less often (31%) on other wards. However, this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Patient characteristics for subjects with and without ECG recording after drug–drug interaction overriding

| Post ECG (n= 56) | No post ECG (n= 112) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 24 (43%) | 49 (44%) | NS |

| Age > 65 years | 29 (52%) | 58 (52%) | NS |

| Cardiovascular disease | 51 (91%) | 67 (60%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18 (32%) | 25 (22 %) | NS |

| Renal failure (GFR < 50 ml min−1)* | 20 (38%) | 23 (26%) | NS |

| Potassium level < 3.5 mmol l−1† | 3 (5.7%) | 7 (7.6%) | NS |

| Average number of risk factors | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 2.0 ± 1.2 | <0.01 |

| CI 0.3, 4.8 | CI −0.3, 5.2 | ||

| Average number of alerts per patient | 4.4 ± 3.8 | 2.2 ± 2.2 | <0.001 |

| CI −3.3, 12.0 | CI −2.2, 6.5 | ||

| Average number of alert days per patient | 2.8 ± 2.4 | 1.7 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| CI −2.0, 7.7 | CI −0.6, 4.1 | ||

| Combination of at least 2 class 1 drugs | 23 (41%) | 35 (31%) | NS |

| Cardiology ward | 13 (23%) | 16 (14%) | NS |

Calculated on all patients in whom an estimated GFR was available (n= 52 and 89, respectively).

Calculated on all patients with known potassium level (n= 53 and 92, respectively). CI, 95% confidence interval; GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

In 49 patients (29%) an ECG before and after start of the drug that generated the QTc alert was available, allowing the change in QTc interval to be calculated. In 51% of these cases, QTc interval prolongation was found, and in 31% this was to such an extent that the patient was considered at risk for TdP. Fifty-one percent of the patients were already using one QT-prolonging drug at the time of their first ECG recording.

The 25 patients in whom a prolonged QTc interval was found on the ECG made following DDI overriding are presented in Table 4. The number of risk factors ranged from one to five, and the drugs generating the alert ranged from high risk (class 1) to low risk (class 4). The majority of these patients (88%) were using two QT-prolonging drugs. One patient, not presented in Table 4 because his QTc interval remained <450 ms, was also considered at risk for TdP because he showed an increase in QTc interval of 75 ms upon starting the combined treatment with domperidone and amitriptyline (class 1 and 4). Two patients in whom the ECG criteria did not fulfil the criteria for an increased risk of TdP did develop ventricular arrhythmias, possibly due to the contribution of other risk factors. One patient used cisapride, which has been withdrawn from the market in certain countries in view of known risk of TdP in combination with several drugs.

Table 4.

Subjects with prolonged QTc interval (n= 25)

| Gender | Age, years | Cardiovascular disease | Diabetes mellitus | GFR, ml min−1 | K+ level, mmol l−1 | No. of risk factors | Drug 1 | Drug 2 | Drug 3 | QTc2, ms | ΔQTc, ms | Risk TdP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 75 | + | + | 13 | 4.1 | 5 | Haloperidol (1) | Amiodarone (1) | – | 504 | 29 | + |

| Female | 70 | + | + | 58 | 3.8 | 4 | Haloperidol (1) | Amiodarone (1) | Cotrimoxazole (4) | 487 | 47 | −† |

| Female | 71 | + | − | 37 | 4.2 | 4 | Indapamide (2) | Promethazin (NC) | – | 470 | 64 | + |

| Male | 54 | + | + | 33 | 4.3 | 3 | Haloperidol (1) | Pentamidine (1) | – | 499 | 49 | − |

| Male | 68 | + | − | 49 | 4.1 | 3 | Amiodarone (1) | Haloperidol (1) | – | 487 | 100 | + |

| Male | 72 | + | − | 48 | 3.9 | 3 | Amiodarone (1) | Ketanserin (NC) | – | 537 | 83 | + |

| Male | 94 | + | − | 25 | 4 | 3 | Amiodarone (1) | Haloperidol (1) | Claritromycine (1) | 461 | 19 | − |

| Female | 62 | + | − | 7 | 4.2 | 3 | Amiodarone (1) | Tacrolimus (2) | – | 592 | 201 | + |

| Female | 53 | + | − | 49 | 4.1 | 3 | Haloperidol (1) | Tacrolimus (2) | – | 530 | 62 | + |

| Male | 72 | + | − | 22 | 3.7 | 3 | Indapamide (2) | Haloperidol (1) | – | 462 | 30 | − |

| Male | 73 | + | + | 3* | Domperidone (1) | Cotrimoxazole (4) | – | 453 | 25 | − | ||

| Male | 72 | + | − | 48 | 3.9 | 3 | Sotalol (1) | Erythromycin (1) | – | 501 | 32 | + |

| Male | 51 | + | + | 33 | 4.4 | 3 | Tacrolimus (2) | Mianserin (NC) | – | 510 | 122 | + |

| Male | 67 | + | − | 65 | 4.4 | 2 | Sotalol (1) | Haloperidol (1) | Cisapride (1) | 467 | 25 | − |

| Male | 68 | + | − | >90 | 4.4 | 2 | Chloorpromazine (1) | Cisapride (1) | 490 | 64 | + | |

| Male | 61 | + | − | 26 | 4.1 | 2 | Haloperidol (1) | Sotalol (1) | – | 478 | 84 | + |

| Male | 64 | + | + | 77 | 4.7 | 2 | Sotalol (1) | Amiodarone (1) | – | 502 | 73 | + |

| Male | 63 | + | + | 3.8 | 2* | Sotalol (1) | Amiodarone (1) | – | 483 | −29 | −† | |

| Male | 64 | + | + | 2* | Chloorpromazine (1) | Ketanserin (NC) | – | 467 | 91 | + | ||

| Male | 64 | + | − | 59 | 4.0 | 1 | Haloperidol (1) | Amiodarone (1) | – | 560 | 141 | + |

| Male | 41 | + | − | 69 | 3.9 | 1 | Haloperidol (1) | Amiodarone (1) | – | 475 | 48 | − |

| Male | 64 | + | − | 79 | 3.3 | 1 | Sotalol (1) | Claritromycine (1) | – | 485 | 10 | − |

| Male | 56 | + | − | 80 | 4.8 | 1 | Sotalol (1) | Amiodarone (1) | – | 464 | 24 | − |

| Male | 45 | + | − | >90 | 4.2 | 1 | Haloperidol (1) | Tacrolimus (2) | – | 492 | 84 | + |

| Male | 36 | + | − | 60 | 3.7 | 1 | Tacrolimus (2) | Haloperidol (1) | – | 461 | 16 | − |

Patients are categorized according to number of risk factors. +, present; −, absent; GFR, glomerular filtration rate in ml min−1; TdP, torsades de pointes; (), drug class according to http://www.torsades.org; NC, drug not classified on http://www.torsades.org

QTc2, QTc interval after QTc-alert overriding; ΔQTc, change in QTc-interval ECG before and ECG after QTc alert.

Number of risk factors might have been higher due to unknown values.

Patient with ventricular arrhythmias. Italics, QTc-prolonging drug(s) started at time of QTc alert.

For all patients with cardiovascular morbidity the type of cardiovascular disease and the cardiovascular drugs used are shown in Table 5. The average number of cardiovascular diseases in these patients was 1.5 and they used on average of 2.2 different cardiovascular drug classes.

Table 5.

Cardiovascular diseases and drugs

| Cohort n= 168 | Post ECG n= 56 | No post ECG n= 112 | Prolonged QTc interval n= 25 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with cardiovascular disease | 116 | 51 | 67 | 25 |

| Diseases | ||||

| Myocardial Infarction | 17 (15%) | 9 (18%) | 8 (12%) | 7 (28%) |

| Heart failure | 25 (22%) | 15 (29%) | 10 (15%) | 10 (40%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 33 (28%) | 16 (31%) | 17 (25%) | 8 (32%) |

| Hypertension | 49 (42%) | 22 (43%) | 27 (40%) | 7 (28%) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 9 (8%) | 6 (12%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (8%) |

| Peripheral atherosclerotic vasculopathy | 4 (3%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (8%) |

| Angina pectoris | 14 (12%) | 4 (8%) | 10 (15%) | 3 (12%) |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 12 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (18%) | 0 (0%) |

| Drugs | ||||

| Diuretics | 55 (47%) | 19 (37%) | 36 (54%) | 11 (44%) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 20 (17%) | 12 (24%) | 8 (12%) | 5 (20%) |

| β-Blockers | 68 (59%) | 28 (55%) | 40 (60%) | 12 (48%) |

| RAAS inhibitors | 64 (55%) | 32 (63%) | 32 (48%) | 21 (84%) |

| Nitrates | 21 (18%) | 8 (16%) | 13 (19%) | 4 (16%) |

| Digoxin | 13 (11%) | 6 (12%) | 7 (10%) | 3 (12%) |

| Amiodarone | 16 (14%) | 8 (16%) | 8 (12%) | 5 (20%) |

RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system.

For each case a control patient using one QTc-prolonging drug was selected to evaluate within-patient variability in the QTc interval. Patient characteristics presented in Table 6 show that the groups were similar, except for the first QTc interval. QT prolongation and risk of TdP were significantly more pronounced in cases with additional QT-prolonging drug(s) compared with the controls that continued one QT-prolonging drug. In the control group, the proportion of patients with an increased risk of TdP, based on QTc interval, did not change (QTc interval 10% for both first and second ECG), whereas in patients in whom an additional QTc-prolonging drug was started this percentage increased from 4 to 31%.

Table 6.

Patient characteristics cases (with QTc-alert overrides) and controls (using one QTc-prolonging drug)

| Cases (n= 49) | Controls (n= 48) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender female | 20 (41%) | 20 (42%) | NS |

| Cardiovascular disease | 44 (90%) | 45 (94%) | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus | 17 (35%) | 18 (37%) | NS |

| Renal failure (GFR < 50 ml min−1)* | 19 (42%) | 13 (33%) | NS |

| Mean age (years) | 65 ± 12 | 62 ± 15 | NS |

| CI 42, 88 | CI 32, 92 | ||

| Potassium level (mmol l−1) | 4.14 ± 0.49 | 4.24 ± 0.57 | NS |

| CI 2.90, 4.86 | CI 3.11, 5.38 | ||

| Average QTc interval ECG1 (ms) | 430 ± 32 | 451 ± 37 | <0.005 |

| CI 366, 493 | CI 377, 524 | ||

| Average QTc interval ECG2 (ms) | 461 ± 44 | 447 ± 33 | NS |

| CI 372, 549 | CI 381, 512 | ||

| Δ QTc (ms) | +31 | −4 | <0.001 |

| CI −72, 133 | CI −80, 72 | ||

| Prolonged QTc interval ECG1 | 7 (14%) | 19 (40%) | <0.005 |

| Prolonged QTc interval ECG2 | 25 (51%) | 15 (31%) | <0.05 |

| Increased risk TdP ECG1 | 2 (4%) | 6 (10%) | NS |

| Increased risk TdP ECG 2 | 15 (31%) | 5 (10%) | <0.025 |

Calculated on all patients with an estimated GFR (n= 45 and 39, respectively). CI, 95% confidence interval; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; TdP, torsades de pointes.

Discussion

It was expected that a physician overriding a QTc-prolongation alert in the CPOE would decide to record an ECG within a period of about 1 week. This ECG could then be used for the decision whether continuation of the initiated combination was justified. However, ECGs were recorded in only a small percentage of patients with overridden QTc alerts (25% within 1 week, 33% within 1 month). Patients for whom an ECG was recorded more often suffered from cardiovascular diseases, had a higher number of risk factors for QTc prolongation and had a higher number of QTc overrides and more different days with QTc overrides. From our study we cannot distinguish whether ECGs were made because of cardiovascular comorbidity or because of the QTc alert. The percentage of ECGs recorded due to the alert only may even be <33%.

Several factors may explain why in only so few cases was an ECG recorded. First, the upper part of the alert text, which is seen at a glance (see Figure 1), draws attention to a serious adverse event (serious arrhythmias), but the words ‘may’ and ‘possibly’ weaken its impact. Furthermore, a recommendation to record an ECG is lacking in the first sentences and can be read only if the alert text is scrolled down. If the user decides to record an ECG, the CPOE provides no possibility of ordering it electronically. Even on cardiology wards with more understanding of the seriousness of TdP and with more possibilities for recording an ECG, alerts on QTc-prolonging drug combinations resulted in ECGs in only 45% of patients. Possibly, physicians assumed that despite the alert, the absolute risk of a serious arrhythmia remained low, and therefore overriding the alert would probably not result in adverse events.

Besides these problems on information content, low incidence, and handling possibilities, a specificity problem plays a role. Specificity has several aspects: relevance, urgency and accuracy. An alert is specific if it is not of minor importance (relevance), requires action (urgency) and is presented at the patient level, making use of gender, age, and serum levels (accuracy) [12]. The alerts on QTc prolongation are relevant because serious arrhythmias may result from overriding and only drugs with clinical evidence for TdP have been included in alert generation, and are urgent because the action of making an ECG is required, but they lack accuracy. Alert generation is not being tailored to female gender, older age, low potassium serum levels and bad renal function, and does not take into account comorbidity (cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus) and drug dose. This is caused by the fact that the majority of Dutch CPOEs do not have a link either with laboratory data or with clinical information of the patient.

It is unclear why ECGs were more often recorded in patients with a higher number of overridden alerts. We did not check the number of ECGs recorded, but only whether an ECG had been recorded, so it remains unknown whether a certain percentage of alerts did result in ECGs, or that a kind of alert threshold had to be exceeded before ECG recording took place. Furthermore, different physicians involved might have had different actions.

Error management

Drug safety alerts are incorporated in CPOE systems with the aim to make potential errors visible and thus prevent patient harm [13, 14]. High sensitivity is strived for to limit the incidence of potentially dangerous prescribing errors. High specificity is necessary to prevent data overload.

To improve specificity substantially, all risk factors for developing TdP should be taken into account for alert generation. However, it is not clear to what extent the different risk factors add to the overall risk. These partial contributions should first be elucidated before accurate alert generation can take place. In case of combinations of QTc-prolonging drugs, ECGs just before and after combining such drugs should be recorded, and risk factors collected. Because of the urgency of the required action (preferably before starting the new drug), an unambiguous recommendation to record an ECG before and after starting a combination should be given in the first sentence of the alert text. If postponement of starting the drug combination is not desirable, a single ECG after combination can also give useful information. The hospital pharmacist can play a role in checking whether ECGs are recorded. If partial contributions of risk factors for QTc prolongation are known, clinical rules incorporating this knowledge can be developed to improve specificity.

The advice to keep showing low specificity alerts to physicians seems contrary to the conclusion that high specificity is necessary to prevent data overload. Direction to someone else in the workflow, which is a useful alternative for low specificity alerts, is not feasible in case of QTc alerts because the action of ECG recording is urgent (should take place before starting the drug) and is necessary to quantify the risk of developing TdP. Without ECGs, someone else in the workflow cannot handle the alert either.

The fact that amiodarone is frequently involved in subjects with prolonged QTc interval or risk of TdP would suggest that special caution should be taken in patients using this drug. However, amiodarone has been shown to cause TdP rarely despite QTc-interval prolongation, which can probably be explained by its action on both sodium and calcium channels, preventing after-depolarizations [15].

Strengths and weaknesses

This study has revealed the problem of a low percentage of ECGs recorded after QTc-alert overriding and has shown several causes for this overriding. Furthermore, it has shown an increase in the average QTc interval and in the percentage patients at risk for developing TdP in cases. Within-patient variability in the QTc interval was shown to be of minor importance by comparing cases with controls.

This study had several limitations. It was performed retrospectively during 6 months, in one hospital, with a relatively small number of patients with ECGs recorded before and after overriding QTc alerts. Unfortunately, alerts resulting in prescription cancellation cannot be logged by the system, so only overridden alerts could be studied. Motives for ECG recordings remained unknown and might be induced by alerts as well as by other patient conditions, such as cardiovascular comorbidity. Potassium or creatinine levels were sometimes unknown due to the retrospective nature of the study and therefore the number of risk factors might be higher than calculated. Several comparisons did not reach statistical significance due to small patient numbers. The study was underpowered to predict which patients might develop TdP, and a prospective study should be performed to study the extent to which different risk factors add to the overall risk of TdP. We analysed QTc prolongation to assess the risk of TdP. Although this relationship is not clear-cut, this is the best way to study it, as TdP has a low incidence. Patients on the combination tacrolimus and cotrimoxazole were excluded from this study because of a perceived low risk of TdP, as these drugs are categorized in class 2 and 4 and the protocolized cotrimoxazole dose of 480 mg daily to prevent Pneumocystis carinii infection is low. As several combinations with class 2 and class 4 drugs did result in considerable QTc prolongation with increased risk of TdP, it can be questioned whether this combination is really low risk.

The first ECGs of the control group and the cases were not comparable with respect to the QTc interval. This can be explained by the fact that the percentage of patients using one QT-prolonging drug was 51% for cases and 100% for controls. This did not pose a problem, however, as the change in QTc interval was significantly more pronounced in cases than in controls.

Conclusion

Our study has shown that in only 33% of patients in whom a combination of two or more QTc-prolonging drugs had been initiated was an ECG recorded, despite the QTc alert shown to the prescribing physician. In those patients for whom an ECG was recorded, it remained unclear whether ECG recording was the result of the QTc alert or of other considerations. Patients with ECG recordings appeared to have more risk factors, more alert overrides and more days on which alerts were overridden.

For those subjects with ECGs before and after overriding the QTc alert, 51% had QTc-interval prolongation and 31% was considered at increased risk for TdP. This was due to many different drug combinations with drugs known for their potential to result in TdP as well as drugs unlikely to cause TdP or not classified as such.

QTc prolongation was statistically significantly more pronounced in the cases (due to addition of at least one QTc-prolonging drug) than in the control group that continued one QTc-prolonging drug. The low proportion of patients in whom an ECG was made following the alert, and the high prevalence of clinically important QTc prolongation in patients in whom ECGs were made, prompt us to recommend being more vigilant in such cases. Prescribing physicians should receive more information on the necessity of checking QTc intervals after initiating combinations of QTc-prolonging drugs. Pharmacists could send out reminders to those who do not comply.

Competing interests

None to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morganroth J, Brown AM, Critz S, Crumb WJ, Kunze DL, Lacerda AE, Lopez H. Variability of the QTc interval: impact on defining drug effect and low-frequency cardiac event. Am J Cardiol. 1993;72:26B–31B. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90037-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roden MD. Drug-induced prolongation of the QT interval. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1013–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Ponti F, Poluzzi E, Montanaro N. Organising evidence on QT-prolongation and occurrence of Torsade de Pointes with non-antiarrhythmic drugs: a call for consensus. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57:185–209. doi: 10.1007/s002280100290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Straus SMJM, Kors J, De Bruin ML, van der Hooft CS, Hofman A, Heeringa J, Deckers JW, Kingma JH, Sturkenboom MC, Stricker BH, Witteman JC. Prolonged QTc interval and risk of sudden cardiac death in a population of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:362–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen LaPointe NM, Curtis LH, Chan KA, Kramer JM, Lafata JE, Gurwitz JH, Raebel MA, Platt R. Frequency of high-risk use of QT-prolonging medications. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:361–8. doi: 10.1002/pds.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Khatib SM, LaPointe NMA, Kramer JM, Califf RM. What clinicians should know about the QT interval. JAMA. 2003;289:2120–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Ponti F, Poluzzi E, Montanaro N. QT-interval prolongation by non-cardiac drugs: lessons to be learned from recent experience. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;56:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s002280050714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Bruin M, Hoes A, Leufkens HGM. QTc-prolonging drugs and hospitalization for cardiac arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:59–62. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02998-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benoit SR, Mendelsohn AB, Nourjah P, Staffa JA, Graham DJ. Risk factors for prolonged QTc among US adults: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12:363–8. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000173110.21851.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viskin S. Long QT syndrome caused by noncardiac drugs. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;45:415–27. doi: 10.1053/pcad.2003.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Roon EN, Flikweert S, le Comte M, Langendijk PN, Kwee-Zuiderwijk WJ, Smits P, Brouwers JR. Clinical relevance of drug–drug interactions: a structured assessment procedure. Drug Saf. 2005;28:1131–9. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200528120-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, Berg M. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:138–47. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nolan TW. System changes to improve patient safety. BMJ. 2000;320:771–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reason J. Human error: models and management: lessons from aviation. BMJ. 2000;320:781–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazzara R. Amiodarone and Torsade de Pointes. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:549–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-7-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]