Abstract

Anal stenosis is a rare but serious complication of anorectal surgery, most commonly seen after hemorrhoidectomy. Anal stenosis represents a technical challenge in terms of surgical management. A Medline search of studies relevant to the management of anal stenosis was undertaken. The etiology, pathophysiology and classification of anal stenosis were reviewed. An overview of surgical and non-surgical therapeutic options was developed. Ninety percent of anal stenosis is caused by overzealous hemorrhoidectomy. Treatment, both medical and surgical, should be modulated based on stenosis severity. Mild stenosis can be managed conservatively with stool softeners or fiber supplements. Sphincterotomy may be quite adequate for a patient with a mild degree of narrowing. For more severe stenosis, a formal anoplasty should be performed to treat the loss of anal canal tissue. Anal stenosis may be anatomic or functional. Anal stricture is most often a preventable complication. Many techniques have been used for the treatment of anal stenosis with variable healing rates. It is extremely difficult to interpret the results of the various anaplastic procedures described in the literature as prospective trials have not been performed. However, almost any approach will at least improve patient symptoms.

Keywords: Anal canal surgery, Anal stenosis, Anoplasty, Hemorrhoidectomy, Complications, Lateral internal sphincterotomy, Surgical flap

INTRODUCTION

Anal stenosis is an uncommon disabling condition[1–5]. It is a narrowing of the anal canal. This narrowing may result from a true anatomic stricture or a muscular and functional stenosis. In anatomic anal stenosis, the normal pliable anoderm, to a varying extent, is replaced with restrictive cicatrized tissue. Stenosis produces a morphologic alteration of the anal canal and a consequent reduction of the region’s functionality, leading to difficult or painful bowel movements[6–8].

Anal stenosis is a serious complication of anorectal surgery. Stenosis can complicate a radical amputative hemorrhoidectomy in 5%-10% of cases[9–14], particularly those in which large areas of anoderm and hemorrhoidal rectal mucosa from the lining of the anal canal is denuded, but can also occur after other anorectal surgical procedures.

Treatment, both medical and surgical, should be modulated based on stenosis severity[4,15]. Mild stenosis can be managed conservatively with stool softeners or fiber supplements. Daily digital or mechanical anal dilatations may be used. Sphincterotomy may be quite adequate for a patient with a mild degree of narrowing. For more severe anal stenosis, a formal anoplasty should be performed to treat the loss of anal canal tissue. Several techniques have been described for the treatment of moderate to severe stenosis refractory to non-operative management. In the literature, several studies have been conducted on anal stenosis treatment, but there is not yet universal consent on the anaplastic procedure to use. This review examines some of the evidence concerning the surgical treatment of anal stenosis.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Stenosis may be caused by an intrinsic or extrinsic pathologic process of the anorectum. Anal stenosis may follow almost any condition that causes scarring of the anoderm. The causes of anal stenosis include surgery of the anal canal, trauma, inflammatory bowel disease, radiation therapy, venereal disease, tubercolosis, and chronic laxative abuse. We focus on the treatment of postsurgical anal stenosis.

Ninety percent of anal stenosis is caused by overzealous hemorrhoidectomy[16]. Removal of large areas of anoderm and hemorrhoidal rectal mucosa, without sparing of adequate muco-cutaneous bridges, leads to scarring and a progressive chronic stricture. The surgical procedure influences the incidence of anal stenosis, particularly after “Whitehead hemorrhoidectomy” because, later, surgeons misinterpreted Whitehead’s description and anchored the mucosa to the anal verge (Whitehead deformity)[14,17–19]. After Milligan-Morgan and stapled rectal mucosectomy (SRM), stenosis is less frequent. In a study of 1107 patients treated with stapled hemorrhoidectomy, 164 of 1107 patients registered a complication: anal stenosis was observed in only 0.8% of cases[19]. Stenoses caused by SRM are presumably rectal stenoses, since the causing event was a resection of rectal mucosa. The stenosis rate following stapled mucosectomy generally ranges from 0.8%-5.0%. The calculated actuarial one-year stenosis rate is 6%, which is higher than the above-mentioned published stenosis rates.

In addition, anal fissure surgery can lead to anal stenosis, if an internal sphincterotomy is not performed. Stenosis may follow anterior resection of the rectum, if complicated by anastomotic dehiscence. Inflammatory bowel diseases may cause anal stenosis, particularly Crohn’s disease. These stenoses are characterized by a transmural scarred inflammatory process. Patients with anal fissure or who abuse paraffin laxatives may develop a disuse stenosis. Radiotherapy treatment for pelvic tumors (i.e. uterine carcinoma, prostatic carcinoma, etc.) promotes anal stenosis formation. Also sepsis, ischemia from occlusion of lower mesenteric artery or upper rectal artery, AIDS, venereal lymphogranuloma, gonorrhea, amoebiasis and anorectal congenital disease may lead to anal stenosis. Finally, chronic abuse of ergotamine tartrate for the treatment of migraine headache attack may lead to anorectal stricture[20].

In the natural anatomic configuration, the anal canal is an upside down funnel, where its diameter is lower than the diameter of the anal verge. Physiologically, during evacuation, the internal sphincter relaxes and dilates to the cutaneous side, where the diameter is greater, to allow the regular passage of stool. On this subject, it is important to distinguish acute from chronic anal stenosis. Acute anal stenosis is determined by a severe and sudden spasm of persistent pain (i.e. in the anal fissure). These spasms are dynamic and reversible. In this case, the ano-rectal passage is cylindrical. Chronic anal stenosis, occurs secondary to surgical procedures, infections and fibrosis, and spasms are adynamic and irreversible[3,4]. Thus, the anal canal progressively reduces its diameter. In patients who use laxatives improperly, physiologic regular dilatation is abolished. Gradual and irreversible fibrosis occurs in the sub-cutaneous space of the anal canal with a pathologic funnel-shaped configuration in which the diameter of the anal canal is greater than the diameter of the anal verge.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of this condition is straightforward. The patient usually reports difficult or painful bowel movements. The patient may also have rectal bleeding and narrow stools. The fear of fecal impaction or pain usually causes the patient to rely on daily laxatives or enemas. Suspicion of anal stenosis is heightened by a history of hemorrhoidectomy, Crohn’s disease, or excessive laxative use.

Physical examination confirms the diagnosis. Visual examination of the anal canal and perianal skin, along with a digital rectal examination, is usually suffice to establish the presence of anal stenosis. Occasionally the patient is too anxious or the anal canal too painful to allow an adequate examination. In this situation, anesthesia is needed to perform a proper examination of the anal canal. The anesthetic abolishes the spasm associated with an acute fissure but will not produce an increased luminal diameter in a patient with a true stenosis. Anorectal manometry is an objective method for assessing anal musculature tone, rectal compliance, anorectal sensation, and verifying the integrity of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex. Several methods are available for obtaining this information. No single method is universally accepted and manometric data from different institutions are difficult to compare. Manometry has been widely used to document sphincter function prior to procedures, such as lateral internal sphincterotomy, which may affect continence.

It is important to ascertain the cause of the stricture in order to determine proper therapy; a malignant disease must be treated by excision or resection, and anal Crohn’s disease is an absolute contraindication to anoplasty[4].

CLASSIFICATION AND TOPOGRAPHY

When planning treatment of anal stenosis, it is useful to categorize the severity of the stenosis. Anatomic anal stenosis may be classified on the grounds of stricture severity, its structure and the level of involvement in the anal canal. On the basis of severity, Milsom and Mazier[6] distinguished mild (tight anal canal can be examinated by a well-lubricated index finger or a medium Hill-Ferguson retractor), moderate (forceful dilatation is required to insert either the index finger or a medium Hill-Ferguson retractor), and severe anal stenosis (neither the little finger nor a small Hill-Ferguson retractor can be inserted unless a forceful dilatation is employed). Furthermore, stenosis may be diaphragmatic (after inflammatory bowel disease, characterized by a thin strip of constrictor tissue), ring-like or anular (after surgical or traumatic lesions, of length less than 2 cm), and tubular (length more than 2 cm). On the basis of the anal canal levels, stenosis may also be distinguished as low stenosis (distal anal canal at least 0.5 cm below the dentate line, 65% of patients), middle (0.5 cm proximal to 0.5 cm distal to the dentate line, 18.5%), high (proximal to 0.5 cm above the dentate line, 8.5%), and diffuse (all anal canal, 6.5% of cases)[6].

TREATMENT

The best treatment of postsurgical anal stenosis is prevention. Adequate anorectal surgery reduces the incidence of anal stenosis[3,16]. It is essential to treat tissues delicately and not to draw them. Also it is important to use absorbable sutures and minimal resection of tissues. Khubchandani[3] condemned the use of manual dilatation under anesthesia for the non-operative treatment of mild to moderate stenosis because the resultant hematoma in the sphincter apparatus may cause fibrosis and progressive stenosis. In Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy, internal sphincterotomy, if necessary, associated with preservation of adequate muco-cutaneous bridges, prevents anal stenosis. However, if anal stenosis is present, treatment should be modulated based on severity, cause and localization[6].

Non-operative treatment is recommended for mild stenosis and for initial care of moderate stenosis. Also, with severe stenosis, conservative treatment can lead to good results, however, surgery is always necessary. The use of stool softeners and fiber supplements with adequate gain of fluids is the basis of non-operative treatment. This gradual and natural dilation is very effective in most patients. Anal dilatation is another important part of this treatment. Anal dilation can be performed daily both digitally or with any of a number of graduated mechanical dilators. Patients are instructed to sit down on the toilet, bear down, and gradually insert the smallest dilator with ample lubrication. If the patient can persist with the dilations on a regular basis, the result is usually excellent. Many patients do not tolerate this procedure. On the other hand, a dilator may tear the canal. In fact, a complication from the use of dilators may itself precipitate the need for surgical intervention. However, it would be a rare circumstance when mild stenosis would require surgery[4].

Moreover, if the patient remained symptomatic with the usual measures, it is important to be certain that anal stenosis is indeed the cause of the patient’s complaints; particularly in the postoperative patient, anal fissure must be ruled out as a possible source of the problem. If stenosis is refractory to non-operative management, surgery represents the last solution. However, a long course of conservative, medical management is indicated in the treatment of mild anal stenosis before resorting to a surgical approach.

Many different surgical techniques have been described for the management of moderate to severe anal stenosis. Moderate stenosis is generally treated initially in the same fashion as mild stenosis. Fiber supplementation is initiated and dilations are carried out if necessary. Furthermore, partial lateral internal sphincterotomy may be quite adequate for a patient with a mild degree of narrowing. This technique is simple and safe and use is limited to functional stenosis. It is important that the sphincterotomy is done in the open fashion so that the associated scarred anoderm is divided at the same time to allow full release of the scar. The resulting wound is then left open and allowed to heal by secondary intent. This provides relief of the partial obstruction and pain caused by the stenosis, but the relief will be short-lived without appropriate medical management. The importance of a high-fiber diet and fiber supplements must be emphasized to the patient and instituted immediately after surgery. Although the results have been reported as excellent[21,22], it is difficult to interpret whether the patients had significant narrowing or spasm associated with the anal fissure.

For more severe anal stenosis, a formal anoplasty should be performed to treat the loss of anal canal tissue. Various types of flaps have been described for anal stenosis which allow delivery of the more pliable anoderm into the anal canal to replace the scarred lining at that level. A lateral internal sphincterotomy is also usually necessary at the time of anoplasty.

Lateral mucosal advancement flap

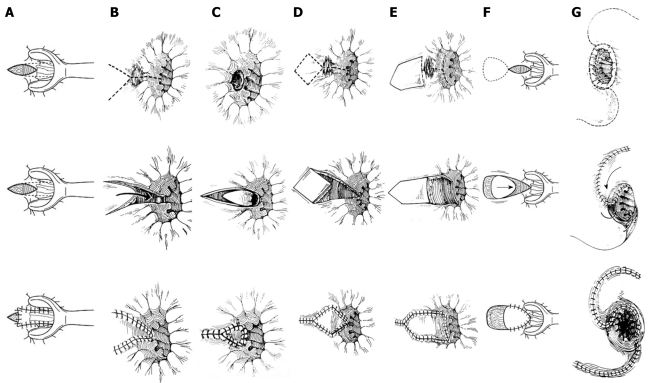

This is a modification of Martin’s anoplasty (Figure 1A)[1,23,24]. A midlevel stenosis is corrected by excision of the scar tissue. An undermining of the proximal rectal and anal mucosa through a transverse incision at the dentate line is performed. An internal sphincterotomy is performed if a functional component is present. The resulting flap is advanced to the distal edge of the internal sphincter near the anal verge. The vascular supply is maintained through the submucosal plexuses. The external part of the wound is left open to minimize ectropion formation.

Figure 1.

Operative procedure for the surgical treatment of anal stenosis. A: Martin’s anoplasty; B: Y-V advancement flap; C: V-Y advancement flap; D: Diamond-shaped flap; E: House-shaped flap; F: U-shaped flap; G: Rotational S-flap.

Y-V advancement flap

This procedure is performed in the gynaecological prone position. It is important to administer adequate antibiotic therapy (cephazoline and metronidazole) at the time of surgery. A mechanical bowel preparation is usually done the day before surgery. After anal dilatation with a medium Hill-Ferguson retractor, the initial incision overlying the area of stricture is the vertical limb of the Y (Figure 1B). This incision is extended on the perianal skin in two directions for creating a V flap. Incisions are carried proximally for 5 to 8 cm. The V flap is incised with fatty subdermal tissue, providing an adequate blood supply. The resulting V advancement flap is sutured into the vertical limb of the Y incision in the anal canal with the internal apex of the triangular flap sutured to the internal sphincter and to rectal mucosa (dentate line) with interrupted long-term absorbable sutures[5,20,23,25–30]. This flap can be done in the posterior midline or in either lateral position. It can also be done bilaterally if needed to relieve the stenosis. Postsurgical management consists of fiber supplements and pain control. Sitz baths can also be instituted to assist with local hygiene. In the post-operative period, a constipating regimen is recommended for 2 d. Antibiotic therapy is usually continued for 7 d. This technique is simple and quite useful for stenosis associated with an anal fissure. However, if more than 25% of the circumference of the anal canal needs to be covered, another anaplastic procedure is indicated[4].

V-Y advancement flap

This procedure is an alternative to Y-V anoplasty. The base of the triangular V flap is sutured to the dentate line (Figure 1C). In addition, the underlying vascular pedicle is contained in the subcutaneous fat. Thus, it is necessary to preserve fatty subcutaneous tissue with wide mobilization to maintain flap viability. The skin is then closed behind the V at the external portion of the perineum to push the V into the anal canal and widen the stenotic area[31].

Diamond-shaped flap

After adequate mechanical bowel preparation and antibiotic therapy in the pre-operative period, this procedure is performed in the gynaecological prone positition. To avoid bleeding, epinephrine can be used. On the basis of stenosis severity, one or two flaps can be created. The scar tissue is incised leaving a diamond-shaped defect (Figure 1D). A diamond-shaped flap is designed so that it will cover the intra-anal portion of the defect[5,23,29]. The preparation of the flap is a crucial step in the procedure: the flap should be well mobilized to reduce tension and to provide enough blood supply to preserve the underlying vascular pedicle.

House flap

After the use of stool softeners in the pre-operative period, enema is performed on the day of surgery. This technique is performed in the gynaecological prone position. If stenosis is extended from the dentate line to perianal skin, a house flap is recommended (Figure 1E). With the use of a Hill-Ferguson retractor, a longitudinal incision is made toward the perianal skin, from the dentate line to the end of the stenosis. The length of incision corresponds to the length of the flap wall. Proximal and distal transverse incisions are centered on the longitudinal incision. The flap is then designed in the shape of a house with the base oriented proximally. The width of the base of the house is designed to match the transverse incisions and hence the width of the mucosal defect to be replaced. It is necessary to preserve the subcutaneous vascular pedicle[2,7,26,31,32]. The flap is then easily advanced into the anal canal and sutured. This procedure offers two advantages: (1) the creation of a wide flap increases the anal canal diameter along its length, (2) the technique allows primary closure of the donor site.

U flap

This procedure is used for the treatment of anal stenosis associated with mucosal ectropion. A U-shaped incision is made in the adjacent perianal skin (Figure 1F). Mobilization and suture of the flap are the same as for diamond-shaped anoplasty. The donor site is left open, and covered with fatty gauzes.

C flap

This procedure is performed in the lithotomy position. With the use of a small Hill-Ferguson retractor, a radial lateral incision is made from the dentate line to the anal verge. Then a C-shaped incision is made in the perianal skin starting from the distal point of radial incision. Preparation of a C flap should guarantee an adequate blood supply.

Rotational S-flap

The S-plasty is best used for the treatment of Bowen’s disease or Paget’s disease, where a large amount of skin has to be excised and new skin rotated into the area[29,33]. The S-plasty does not open a stricture as well as the advancement flap. In the gynaecological prone position, after scar tissue has been excised, a full-thickness S-shaped flap is made in the perianal skin, with the size of the base as great as its length, starting from the dentate line for approximately 8 cm to 10 cm. The flap is then rotated and sutured to the normal mucosa (Figure 1G).

Internal pudendal flap anoplasty

A solitary case report has been reported where extensive coverage was required concomitant with excision of Paget’s disease of the anal canal[34].

Foreskin anoplasty

This interesting operation has been described for the treatment of mucosal ectropion. The procedure uses the foreskin (suitable prepuce) to provide a full-thickness skin graft to the anal canal. Since the initial report by Freeman with six children in 1984[35], no further publications have been noted.

Choise of procedure

The choice of an adequate procedure is related to the extent and severity of the stenosis (Table 1) as it may involve the skin, transitional zone to the dentate line, anal canal, or all of these. Y-V anoplasty is not used in the treatment of stricture above the dentate line. V-Y anoplasty has been used in the treatment of severe low anal stenosis with good results.

Table 1.

Anoplasty for anal stenosis

| Procedures | Indications | Advantages/Disadvantages |

| Partial lateral internal sphincterotomy | Functional stenosis; mild and low stricture in the anal canal | This technique is simple and safe. Use is limited to functional stenosis |

| Mucosal advancement flap | Middle or high localized stricture | Ectropion formation if the flap is sutured at the anal verge |

| Y-V advancement flap | Low and localized stricture below the dentate line | Proximal part of the flap is very narrow and will not allow for a significant widening of the stricture above the dentate line. Also, the tip of the V within the anal canal is subject to ischemic necrosis from lack of mobilization, tension of the flap or loss of vascularization |

| V-Y advancement flap | Mild to severe stricture at the dentate line. Middle or high localized strictures, associated with mucosal ectropion | The tip of the V is subject to ischemic necrosis |

| Diamond flap | Moderate to severe long stricture, localized or circumferential stricture above the dentate line, associated with mucosal ectropion | A diamond-shaped flap is designed so that it will cover the intra-anal portion of the defect. The flap is mobilized with minimal undermining to preserve the integrity of the subcutaneous vascular pedicle |

| House flap | Moderate to severe long stricture, localized or circumferential or diffuse, and stricture above the dentate line, associated with mucosal ectropion | It allows primary closure of the donor site and increases anal canal diameter along its length. Because of the wide base, it avoids the pitfall of having a narrow apex present inside the anal canal that may become ischemic |

| U flap | Moderate to severe stricture, localized or circumferential, associated with mucosal ectropion | This technique is particularly useful when there is need to excise a significant area of ectropion. The donor site is left open |

| C flap | Moderate to severe stricture, localized or circumferential, associated with mucosal ectropion | The donor site is left open |

| Rotational S flap | High severe stricture, circumferential or diffuse, associated with mucosal ectropion | It provides for adequate blood supply, avoids tension, and can be performed bilaterally if necessary for coverage of large areas of skin. Complex technique: high morbidity and longer hospital stay |

Various types of anoplasties with adjacent tissue transfer flaps have been devised to relieve anal stenosis. All of these flaps share the concept of an island of anoderm that is incised completely around its circumference. A significant advantage of these flaps over the Y-V anoplasty is that there is significantly greater mobility of the flap, so it can be advanced well into the anal canal. The diamond flap, House flap, and island flap have all been reported to yield excellent results[3–8,10,15,19,20,22–24–32,34–44]. The type of flap to be used is based on the surgeon’s familiarity and choice as well as the patient’s anatomy and the availability of adequate perianal skin for use in the various flaps. For any of these flaps, the preoperative preparation is the same as for the Y-V flap. A partial lateral internal sphincterotomy is often required as well. Once the flap is fully mobilized, it can be advanced into the anal canal and sutured in place with interrupted long-term absorbable sutures. Similar to the Y-V flap, these flaps can be done in any location and can be done bilaterally if needed.

The House flap is recommended if stenosis extends from the dentate line to perianal skin, allowing primary closure of the donor site and an increase in anal canal diameter along its length. U flap anoplasty is used for the treatment of anal stenosis associated with mucosal ectropion. If less than 50% of the anal circumference is involved, an advancement flap should suffice; however, if 50% or more of the anal canal needs to be reconstructed, a rotational flap of skin should be considered, as it is necessary to cover a large area providing adequate blood supply and avoiding tension.

Postoperative care

Single and limited flaps may be performed in the outpatient setting. For the simplest procedures, patients are started on a high-fiber diet, bulk laxatives and mineral oil for a short time in the postoperative period. Sitz baths and showers are recommended for comfort and hygiene. Flaps with multiple and extensive dissection or reconstruction will require hospital admission. These extensive procedures may require bowel confinement for 3 d to 5 d after which a high-fiber diet is initiated.

Complications

In the literature, various complications have been reported after anoplasty. These include flap necrosis from loss of vascular supply, infection or local sepsis, suture dehiscence from excessive suture line tension, failure to correct the stenosis, donor site problems, sloughing of the flap, ischemic contracture of the edge of the flap, pruritus, urinary tract infection subsequent to Clostridium difficile enterocolitis only in a few cases, fecal incontinence, constipation without stenosis, urinary retention, restenosis and ectropion if the flap is advanced too far and sutured at the anal verge[4–7,10,15,19,20,22,23,25,26,31,32,34,36–39,41,42,44].

COMMENTS

Anal stenosis, although rare, is one of the most feared and disabling complications of anorectal surgery. It has been documented that hemorrhoidectomy is the most frequent cause, but stenosis may be a consequence of other causes. Several operative techniques to treat hemorrhoids have been described. Milligan-Morgan’s open hemorrhoidectomy is most commonly used; other procedures, such as Ferguson’s closed hemorrhoidectomy and Parks’ submucosal hemorrhoidectomy, are technically more complex. We feel that the surgeon’s choice of technique is primarily based on personal experience and technical training, and only a competently performed technique produces satisfying results: hemorrhoidectomy needs skilled operators. If technical guidelines are rigorously followed, the feared complications associated with surgical procedures, such as anal stricture and sphincteric injuries, are largely reduced.

Furthermore, anal stenosis became a focus of interest after the introduction of SRM. Anorectal stenosis is not a specific problem of SRM but is a considerable problem after all anal interventions. In a direct comparison in prospective randomized trials there was no significant difference in stenosis rate between conventional hemorrhoidectomy and SRM. Nevertheless, a substantial rate of stenoses was observed following conventional hemorrhoidectomy, and probably the highest stenosis rate was described after Whitehead hemorrhoidectomy. One potential mechanism that might cause stenosis following SRM is ring dehiscence followed by submucous inflammation. Another theoretical cause is that the stapled ring is placed too deep in the anal canal and that the squamous skin cells react by scarring and shrinking. One major aspect of the potential risk of developing a stenosis is the distance to the anal verge. A full thickness excision of the rectal wall is another potential cause for stenosis after SRM.

A number of corrective surgical procedures have been designed aiming to bring a healthy lining to the narrowed portion of the anal canal. Since more complex techniques, such as S-plasty, have now been abandoned due to high morbidity and longer hospital stay, easier techniques are still being performed with good results (Table 2). The ideal procedure should be simple, should lead to no or minimal early and late morbidity, and should restore anal function with a good long-term outcome.

Table 2.

Experiences in literature

| Authors | No. of cases | Procedure |

Results |

Healing rate (%) | ||

| Good | Fair | Poor | ||||

| Sarner et al[45] | 21 | Sarner’s flap | - | - | - | 100 |

| Nickell et al[46] | 4 | Advancement flap anoplasty | 4 | - | - | 100 |

| Oh et al[41] | 12 | C anoplasty | 11 | - | 1 | 90 |

| Khubchandani[40] | 53 | Advancement flap anoplasty | Nr | Nr | Nr | 94 |

| Milsom et al[6] | 24 | V-Y anosplasty and Sarner’s anoplasty | - | - | - | 90 |

| 1Gingold et al[28] | 14 | Y-V anoplasty | 9 | 5 | - | 64 |

| Caplin et al[11] | 23 | Diamond flap anoplasty | 23 | - | - | 100 |

| Ramanujam et al[30] | 21 | Y-V anoplasty | 18 | 2 | 1 | 95 |

| Pearl et al[29] | 25 | Island flap anoplasty | 16 | 7 | 2 | 92 |

| 2Angelchik et al[23] | 19 | Y-V anoplasty (12 cases) | 8 | 4 | 0 | 100 |

| Diamond flap anoplasty (7 cases) | 7 | - | - | 100 | ||

| Pidala et al[42] | 28 | Island flap anoplasty | 25 | 3 | 91 | |

| Eu et al[38] | 9 | Lateral internal sphincterotomy (5 patients) and anoplasty (4 cases) | 9 | - | - | 100 |

| Gonzalez et al[39] | 17 | S anoplasty (6 cases) and advancement flap anoplasty (11 cases) | 16 | - | 1 | 92 |

| Sentovich et al[32] | 29 | House advancement flap | 26 | - | 3 | 90 |

| Saldana et al[34] | 1 | Internal pudendal flap anoplasty | 1 | - | - | 100 |

| Aitola et al[25] | 10 | Y-V anoplasty with internal sphincterotomy | 6 | 3 | 1 | 60 |

| de Medeiros[47] | 30 | Sarner’s flap or Musiani’s flap | - | - | - | 100 |

| Maria et al[5] | 42 | Y-V anoplasty (29 cases) | 26 | - | 3 | 90 |

| Diamond flap anoplasty (13 cases) | 13 | - | - | 100 | ||

| Stratmann et al[44] | 3 | - | - | - | - | 100 |

| Ettorre et al[26] | 1 | House advancement flap | 1 | - | - | 100 |

| Saylan[20] | 3 | Y-V anoplasty | - | - | - | 100 |

| 3Rakhmanine et al[24] | 95 | Lateral mucosal advancement anoplasty | 74 | - | 8 | 90 |

| Carditello et al[36] | 149 | Internal sphincterotomy and mucosal flap anoplasty | Nr | Nr | Nr | 97 |

| Habr-Gama et al[15] | 77 | Sarner’s flap (58 patients) and Musiani’s flap (19 patients) | - | - | - | 87 |

| Filingeri et al[27] | 7 | Y-V anoplasty | - | - | - | 100 |

| Casadesus et al[1] | 19 | Y-V anoplasty (7 patients) and lateral mucosal advancement flap anoplasty (12 patients) | - | - | - | 100 |

| Alver et al[31] | 8 | House advancement flap (14 flaps: 1 flap for 2 patients, and 2 flaps for 6 patients) | 6 | - | - | 100 |

Nr: Not reported.

No sphincterotomies were done;

Not all patients underwent sphincterotomy, and some of the procedures were for anal ectropion;

Depending on the degree of stenosis, patients initially underwent either unilateral (62%) or bilateral (38%) anoplasty. Thirteen patients with a follow up of less than 6 mo were excluded from the analysis for restenosis.

Each of the surgical techniques described can be performed safely and have been used with variable healing rates. It is extremely difficult to interpret the results of the various anaplastic procedures in the literature for the obvious reason that prospective trials have not been performed. There are no controlled studies on the advantages and disadvantages of the various anaplastic maneuvers; however, almost any approach will at least improve symptoms in the patient. Oh and Zinberg[41] used C anoplasty in 12 patients with anal stenosis (10 by previous hemorrhoidectomy, 1 by fistulectomy and 1 by fissurectomy), and 11 patients obtained satisfactory results with a total healing rate of 91%. Khubchandani[3] published a study in which 53 patients underwent mucosal advancement flap anoplasty with a healing rate of 94%. Similar results have been reported in a total of 33 patients treated with Y-V anoplasty in two studies[23,28]. A total healing rate of 100% was obtained using diamond flap anoplasty in a total of 23 patients affected by anal stricture and mucosal ectropion. The healing rate was 91.5% in 53 patients who suffered from anal stenosis and ectropion treated with island flap anoplasty[29,39].

Aitola and coworkers[25] conducted a retrospective study in 10 patients who had undergone Y-V anoplasty combined with internal sphincterotomy between 1991 and 1995. After a median follow up period of 12 mo, all but one patient improved. Six patients had good results, three had fair results and in one the result was poor. This patient later developed a restenosis. Total healing rate was 60% with improvement rate of 30%. In a recent study[5], a Y-V anoplasty was perfomed in 29 cases and a diamond flap anoplasty in the remaining 13 cases. At 2 years follow-up, all patients who underwent diamond flap anoplasty had complete resolution of the stenosis (healing rate 100%). Among 29 patients who underwent Y-V anoplasty, 26 (90%) judged their clinical results as excellent while 3 patients (10%) required periodical use of anal dilators. Those three patients had post-operative complications (two suture dehiscence and one ischemic contracture of the edge of the flap).

Rakhmanine and colleagues[24] published a study in which 95 patients underwent lateral mucosal advancement anoplasty. Mean follow up was 50 mo. Only 63% of patients had undergone previous surgery: 35 patients had had hemorrhoidectomy, 10 operations for anal fissure, 4 for fistula, 1 transversal excision of a neoplasm and 10 other operations. The overall complication rate was 3% (one abscess and two seepage of liquid stool).

CONCLUSION

Anal stenosis is most often a preventable complication. A well-performed hemorrhoidectomy is the best preventative measure. Anoplasty should be part of the armamentarium of colorectal surgeons for treating severe anal stenosis. The anatomic configuration of the anorectum and perianal region is very complex and knowledge of this area is essential before performing any surgical procedure. Most post-anoplasty complications can be avoided by respecting the rectal wall anatomy in the execution of surgical procedures. The preparation of flaps is important for treatment success. In all cases, in fact, it is necessary to preserve as much sub-cutaneous fat as possible with wide mobilization, and to maintain viability and to avoid excessive suture line tension. In addition, it is important to treat tissues delicately and not to draw them, to use absorbable sutures and perform minimal tissue resection.

Peer reviewer: Luigi Bonavina, Professor, Department of Surgery, Policlinico San Donato, University of Milano, via Morandi 30, Milano 20097, Italy

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Casadesus D, Villasana LE, Diaz H, Chavez M, Sanchez IM, Martinez PP, Diaz A. Treatment of anal stenosis: a 5-year review. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:557–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen MA, Pitsch RM Jr, Cali RL, Blatchford GJ, Thorson AG. "House" advancement pedicle flap for anal stenosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:201–203. doi: 10.1007/BF02050680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khubchandani IT. Anal stenosis. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:1353–1360. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liberman H, Thorson AG. How I do it. Anal stenosis. Am J Surg. 2000;179:325–329. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maria G, Brisinda G, Civello IM. Anoplasty for the treatment of anal stenosis. Am J Surg. 1998;175:158–160. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milsom JW, Mazier WP. Classification and management of postsurgical anal stenosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1986;163:60–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owen HA, Edwards DP, Khosraviani K, Phillips RK. The house advancement anoplasty for treatment of anal disorders. J R Army Med Corps. 2006;152:87–88. doi: 10.1136/jramc-152-02-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parnaud E. Leiomyotomy with anoplasty in the treatment of anal canal fissures and benign stenosis. Am J Proctol. 1971;22:326–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boccasanta P, Capretti PG, Venturi M, Cioffi U, De Simone M, Salamina G, Contessini-Avesani E, Peracchia A. Randomised controlled trial between stapled circumferential mucosectomy and conventional circular hemorrhoidectomy in advanced hemorrhoids with external mucosal prolapse. Am J Surg. 2001;182:64–68. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00654-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boccasanta P, Venturi M, Orio A, Salamina G, Reitano M, Cioffi U, Floridi A, Strinna M, Peracchia A. Circular hemorrhoidectomy in advanced hemorrhoidal disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:969–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caplin DA, Kodner IJ. Repair of anal stricture and mucosal ectropion by simple flap procedures. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:92–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02555384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutherland LM, Burchard AK, Matsuda K, Sweeney JL, Bokey EL, Childs PA, Roberts AK, Waxman BP, Maddern GJ. A systematic review of stapled hemorrhoidectomy. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1395–1406; discussion 1407. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.12.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson MS, Pope V, Doran HE, Fearn SJ, Brough WA. Objective comparison of stapled anopexy and open hemorrhoidectomy: a randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1437–1444. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6446-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolff BG, Culp CE. The Whitehead hemorrhoidectomy. An unjustly maligned procedure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:587–590. doi: 10.1007/BF02556790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habr-Gama A, Sobrado CW, de Araujo SE, Nahas SC, Birbojm I, Nahas CS, Kiss DR. Surgical treatment of anal stenosis: assessment of 77 anoplasties. Clinics. 2005;60:17–20. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322005000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brisinda G. How to treat haemorrhoids. Prevention is best; haemorrhoidectomy needs skilled operators. BMJ. 2000;321:582–583. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7261.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brisinda G, Brandara F, Cadeddu F, Civello IM, Maria G. Hemorrhoids and hemorrhoidectomies. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1017–1018. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madoff RD, Fleshman JW. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of hemorrhoids. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1463–1473. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ravo B, Amato A, Bianco V, Boccasanta P, Bottini C, Carriero A, Milito G, Dodi G, Mascagni D, Orsini S, et al. Complications after stapled hemorrhoidectomy: can they be prevented? Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:83–88. doi: 10.1007/s101510200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sayfan J. Ergotamine-induced anorectal strictures: report of five cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:271–272. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turell R. Postoperative anal stenosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1950;90:231–233, illust. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sileri P, Stolfi VM, Franceschilli L, Perrone F, Patrizi L, Gaspari AL. Reinterventions for specific technique-related complications of stapled haemorrhoidopexy (SH): a critical appraisal. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1866–1872; discussion 1872-1873. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angelchik PD, Harms BA, Starling JR. Repair of anal stricture and mucosal ectropion with Y-V or pedicle flap anoplasty. Am J Surg. 1993;166:55–59. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80583-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rakhmanine M, Rosen L, Khubchandani I, Stasik J, Riether RD. Lateral mucosal advancement anoplasty for anal stricture. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1423–1424. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aitola PT, Hiltunen KM, Matikainen MJ. Y-V anoplasty combined with internal sphincterotomy for stenosis of the anal canal. Eur J Surg. 1997;163:839–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ettorre GM, Paganelli L, Alessandroni L, Baiano G, Tersigni R. [Anoplasty with House advancement flap for anal stenosis after hemorrhoidectomy. Report of a clinical case] Chir Ital. 2001;53:571–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filingeri V, Gravante G, Cassisa D. Radiofrequency Y-V anoplasty in the treatment of anal stenosis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2006;10:263–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gingold BS, Arvanitis M. Y-V anoplasty for treatment of anal stricture. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1986;162:241–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearl RK, Hooks VH 3rd, Abcarian H, Orsay CP, Nelson RL. Island flap anoplasty for the treatment of anal stricture and mucosal ectropion. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:581–583. doi: 10.1007/BF02052210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramanujam P, Venkatesh KS, Cohen M. Y-V anoplasty for severe anal stenosis. Contemp Surg. 1988;33:62–68. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alver O, Ersoy YE, Aydemir I, Erguney S, Teksoz S, Apaydin B, Ertem M. Use of “house” advancement flap in anorectal diseases. World J Surg. 2008;32:2281–2286. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9699-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sentovich SM, Falk PM, Christensen MA, Thorson AG, Blatchford GJ, Pitsch RM. Operative results of House advancement anoplasty. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1242–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferguson JA. Repair of Whitehead deformity of the anus. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1959;108:115–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saldana E, Paletta C, Gupta N, Vernava AM, Longo WE. Internal pudendal flap anoplasty for severe anal stenosis. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:350–352. doi: 10.1007/BF02049481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freeman NV. The foreskin anoplasty. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:309–313. doi: 10.1007/BF02555638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carditello A, Milone A, Stilo F, Mollo F, Basile M. [Surgical treatment of anal stenosis following hemorrhoid surgery. Results of 150 combined mucosal advancement and internal sphincterotomy] Chir Ital. 2002;54:841–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corno F, Muratore A, Mistrangelo M, Nigra I, Capuzzi P. [Complications of the surgical treatment of hemorrhoids and its therapy] Ann Ital Chir. 1995;66:813–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eu KW, Teoh TA, Seow-Choen F, Goh HS. Anal stricture following haemorrhoidectomy: early diagnosis and treatment. Aust N Z J Surg. 1995;65:101–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1995.tb07270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzalez AR, de Oliveira O Jr, Verzaro R, Nogueras J, Wexner SD. Anoplasty for stenosis and other anorectal defects. Am Surg. 1995;61:526–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khubchandani IT. Mucosal advancement anoplasty. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:194–196. doi: 10.1007/BF02554245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oh C, Zinberg J. Anoplasty for anal stricture. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:809–810. doi: 10.1007/BF02553321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pidala MJ, Slezak FA, Porter JA. Island flap anoplasty for anal canal stenosis and mucosal ectropion. Am Surg. 1994;60:194–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosen L. Anoplasty. Surg Clin North Am. 1988;68:1441–1446. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stratmann H, Kaminski M, Lauschke H, Hirner A. [Plastic surgery of the anorectal area. Indications, technique and outcome] Zentralbl Chir. 2000;125:161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarner JB. Plastic relief of anal stenosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1969;12:277–280. doi: 10.1007/BF02617284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nickell WB, Woodward ER. Advancement flaps for treatment of anal stricture. Arch Surg. 1972;104:223–224. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1972.04180020103022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Medeiros RR. Estenose anal. Analise de 30 casos. Rev Bras Coloproctol. 1997:17: 24–26. [Google Scholar]