Abstract

Despite the growing number of persons with advanced dementia, and the need to improve their end-of-life care, few studies have addressed this important topic. The objectives of this report are to present the methodology established in the CASCADE (Choices, Attitudes, and Strategies for Care of Advanced Dementia at the End-of-Life) study, and to describe how challenges specific to this research were met. The CASCADE study is an ongoing, federally funded, 5-year prospective cohort study of nursing [nursing home (NH)] residents with advanced dementia and their health care proxies (HCPs) initiated in February 2003. Subjects were recruited from 15 facilities around Boston. The recruitment and data collection protocols are described. The demographic features, ownership, staffing, and quality of care of participant facilities are presented and compared to NHs nationwide. To date, 189 resident/HCP dyads have been enrolled. Baseline data are presented, demonstrating the success of the protocol in recruiting and repeatedly assessing NH residents with advanced dementia and their HCPs. Factors challenging and enabling implementation of the protocol are described. The CASCADE experience establishes the feasibility of conducting rigorous, multisite dementia NH research, and the described methodology serves as a detailed reference for subsequent CASCADE publications as results from the study emerge.

Keywords: dementia, palliative care, nursing home, methodology

In the year 2000, over 4.5 million Americans were estimated to have Alzheimer disease. By 2050, the number of those afflicted is expected to exceed 13 million.1 The 85 years and older age group will have the largest proportional increase in the number of cases and the highest percentage of individuals with severe disease.1 Thus, the provision of end-of-life care to the growing number of older persons living to experience the final stages of dementia is an issue of immense clinical and public health importance.

Approximately 70% of Americans with dementia will die in nursing homes (NHs).2 However, few research studies have focused on the experience of older persons with dementia dying in this setting. Limited data suggest that the palliative care currently provided by NHs to these patients and their families may not be optimal.3–12 However, almost all of this earlier work has several design limitations including: retrospective analysis,3–6 conducted in the hospital,7–9 small sample sizes,6–9,12 all male populations,10 and analysis of secondary databases.3–6 Thus, important gaps in knowledge regarding advanced dementia care remain including: the natural history of end-stage disease, the sources of patient suffering, the quality of key decision-making processes, treatment outcomes, health care utilization, and the sources of family burden.

Advancing the methodologic rigor of advanced dementia research is an important initial step toward improving end-of-life care for this condition. Thus, in February 2003, a federally funded, 5-year prospective cohort study of NH residents with advanced dementia and their families was undertaken. The over-riding goal of the CASCADE (Choices, Attitudes, and Strategies for Care of Advanced Dementia at the End-of-Life) study was to elucidate major gaps in knowledge regarding the end-of-life experience in advanced dementia. The specific aims of the CASCADE study included repeated assessment and identification of modifiable aspects of care in the following areas: (1) disease trajectory and clinical course of advanced dementia; (2) resident comfort; (3) clinical decision-making; (4) family satisfaction with end-of-life care, and (5) complicated grief among bereaved family members.

A rigorous, longitudinal investigation, such as the CASCADE study, has not been conducted, in part, because of the particular challenges this work entails. These challenges include: (1) engaging multiple, community nursing facilities research protocols; (2) identifying and recruiting a cohort with advanced dementia; (3) obtaining consent and repeatedly interviewing surrogates to study a very emotional and stressful life experience, and (4) measuring end-of-life outcomes in advanced dementia.

From February 2003 until November 2005, 189 NH residents with advanced dementia and their surrogates have been recruited into the CASCADE study. Recruitment will continue through March 2007, and data collection is ongoing. The objectives of this report are to present the methodology established in the CASCADE study to successfully examine end-of-life care in advanced dementia and to describe how challenges specific to this type of research were met. It is hoped that this shared experience will encourage and be useful to others embarking on this field of investigation, and the described methodology will serve as detailed reference for future CASCADE publications as results from the study emerge.

METHODS

The conduct of this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Hebrew Senior Life.

Study Facilities

Participant facilities were required to have greater than 60 beds, and be located within a 60-mile radius of metropolitan Boston. Participant facilities represented a convenience sample of NHs meeting these criteria. Federal Wide Assurance numbers are needed to conduct research in NHs and were obtained for all facilities.

Based on the literature,5,13–15 facility variables potentially associated with the quality of end-of-life care were obtained, a priori, from the On-Line Survey of Certification of Automated Records (OSCAR),15 and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) Nursing Home Compare website.16 For comparison purposes, these data were also ascertained for all NHs across the US. Demographic data included: the number of beds, racial/ethnic profile (% non-whites), sex (% female), whether the proportion of Medicaid beds exceeded 85%, and whether the facility had a special care dementia unit. Ownership variables included for-profit status and whether the facility was part of a corporate chain. Staffing variables included the number of licensed nurses and nursing assistants per resident per hour per day. Finally, quality indicators included the proportion of high-risk residents with pressure sores, the use of trunk or limb restraints, and the number of deficiencies on the most recent state inspection.16 Quality indicators were not available from one facility because it was licensed as a hospital rather than a NH.

Study Population

The study population was comprised of 2 groups of subjects (ie, dyads): (1) NH residents with advanced dementia and (2) their health care proxies (HCPs).

Eligibility criteria for NH residents with advanced dementia included the following: (1) age ≥65 years, (2) length of NH stay >30 days, (3) Cognitive Performance Score (CPS) equal to 5 or 6,17,18 (4) cognitive impairment due to dementia (any type), (5) Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) equal to 7,19 and (6) a formally or informally appointed HCP was available who could communicate in English. HCPs had to communicate in English because the instruments included in their interviews had not been translated into other languages. Residents in short-term rehabilitation units and those in a coma were excluded. Finally, residents with other causes of severe cognitive impairment (ie, stable major stroke, traumatic brain injury, tumor, or chronic psychiatric conditions) were excluded because their end-of-life course would differ from those with a progressive dementia.

The CPS scale uses 5 variables from the Minimum Data Set (MDS)20 to group residents into the following 7 hierarchical cognitive performance categories; 0=intact, 1=borderline intact, 2=mild impairment, 3=moderate impairment, 4=moderately severe impairment, 5=severe impairment, and 6=very severe impairment. 17,18 The CPS was chosen to screen large NH populations for severe cognitive impairment for the following reasons: (1) the MDS is a federally mandated, standardized assessment instrument, completed on all residents living in licensed US NHs, (2) according to the CPS algorithm, residents are categorized as having a score of 5 or 6 based on single MDS variable; cognitive skills for daily decision-making must be equal to 3 (range 0 to 3, 3 indicates severe impairment), and (3) CPS score is a validated measure of cognitive disability. A CPS score of 5 corresponds to mean Mini-Mental State Examination score of 5.1±(SD)5.3.18

In addition to the CPS score, subjects were also required to be at GDS stage 7. The GDS classifies dementia into 7 stages (1 to 7) based on broad descriptions of the cognitive and functional deficits that typify each stage.19 Although there has been limited validation of the GDS, it is a widely recognized instrument classifying the late stages of dementia. Stage 7 of the GDS is distinguished by the following features: very severe cognitive decline with minimal to no verbal communication, assistance needed to eat and toilet, incontinence of urine and stool, and loss of basic psychomotor skills (eg, may have lost ability to walk).

A 2-stage screening protocol was used to identify eligible subjects. To conduct this screening procedure, a waiver of individual authorization for disclosure of personal health information was granted by the Institutional Review Board at Hebrew Senior Life.

As a first step, computerized MDS data provided by the facility identified residents with CPS scores of 5 or 6 on their most recent assessment. If the facility’s MDS data were not computerized, nurses on all units were asked to identify residents with a CPS score of 5 or 6. In the second step, a research assistant (RA) reviewed the charts of residents with a CPS score of 5 or 6 for eligibility criteria, including dementia as a cause of the cognitive impairment. If the diagnosis of dementia was ambiguous, the residents’ primary care physicians were contacted for their opinions.

An information sheet describing the study was mailed to the HCPs of eligible residents. Unless HCPs requested no further contact, they were telephoned 1 week later to obtain informed consent. HCPs provided consent for themselves and for the residents with advanced dementia.

Screening at each facility was conducted in the aforementioned fashion at the time of initial NH recruitment, and on a quarterly basis thereafter. Entry of individual facilities into the study was staggered because of the intense effort required at the time of initial screening.

Data Collection Protocol

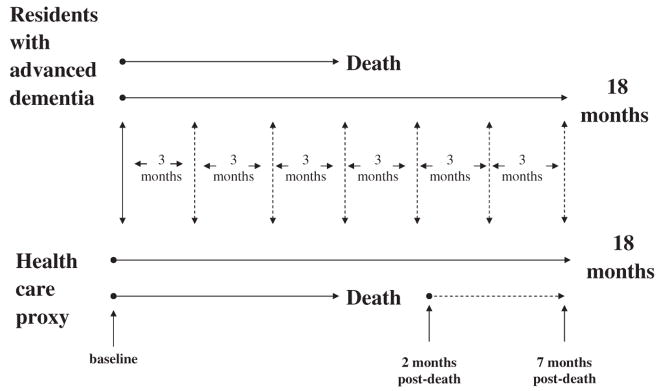

Resident assessments were conducted at baseline and quarterly thereafter for up to 18 months or until death (Fig. 1). If the resident died, a death assessment was completed within 14 days. Resident assessments involved a chart review, a nursing interview, and a brief clinical examination. The follow-up period of 18 months was chosen as a reasonable time to ensure an adequate number of clinical events and deaths would occur to analyze study outcomes.

FIGURE 1.

The CASCADE study data collection protocol. Assessments of residents with advanced dementia were conducted at baseline and quarterly intervals thereafter for up to 18 months or until death. If the resident died, a death assessment was completed within 14 days. HCP assessments were conducted by telephone interviews at baseline and on a quarterly basis thereafter for a maximum of 18 months. If the resident died, HCPs were interviewed 2 and 7 month postdeath.

HCP assessments were conducted by telephone interviews at baseline and on a quarterly basis thereafter for a maximum of 18 months. Every effort was made to conduct HCP interviews within 14 days of the corresponding resident assessment. If the resident died, HCPs were interviewed 2 and 7 month postdeath. Two months was chosen for the first postloss interview to allow enough time to pass after death to maximize the HCP participation, yet proximal enough to death to allow them to remember the circumstances around the dying process. The timing of the 7-month postloss assessment was chosen because a diagnosis of complicated grief requires at least 6 months of symptomatic distress.

HCPs were dropped from the study if they could not be contacted for 2 consecutive assessment periods. If HCPs were lost to follow-up or withdrew, residents within that dyad remained in the study unless the HCPs specifically requested their withdrawal.

Data were collected by 3 trained RAs. In most cases, an individual RA was assigned to specific facilities and collected data from both the resident and HCP comprising a single dyad. These assignments were intended to enhance the establishment of an ongoing relationship between an individual RA with facility staff and HCPs.

Data Collection Elements

Valid and reliable instruments were used to measure data elements whenever possible (Table 1), and measures specifically designed for use in advanced dementia were used if available. The variables needed to achieve the specific aims of the CASCADE study were selected based on the literature,2–14,21–30 and clinical experience. All items had closed-ended response options.

TABLE 1.

CASCADE Data Collection Elements

| Data Collected | Instrument | From | When |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resident Assessments | |||

| Demographics | Chart | Baseline | |

| Medical comorbidity | Chart | Baseline | |

| Medications | Chart | Baseline, quarterly, death | |

| Advance care planning | Chart | Baseline, quarterly, death | |

| Interventions | Chart | Baseline, quarterly, death | |

| Sentinel events | Chart | Quarterly, death | |

| Health services utilization | Chart | Quarterly, death | |

| Comfort | SM-EOLD | Nurse | Baseline, quarterly |

| CAD-EOLD | Nurse | Death | |

| Quality of life | QUALID | Nurse | Baseline, quarterly |

| Functional status | BANS-S | Nurse | Baseline, quarterly |

| Pressure ulcers | Braden | Nurse | Baseline, quarterly |

| Stage | Nurse | Baseline, quarterly, death | |

| Cognitive status | TSI | Resident | Baseline, quarterly |

| Nutritional status | Resident/Chart | Baseline, quarterly | |

| Cause of death | Death certificate | Death | |

| HCP Interviews | |||

| Demographics | HCP | Baseline | |

| Advance care planning | HCP | Baseline, quarterly, 2 mo postloss | |

| Communication | HCP | Baseline, quarterly, 2 mo postloss | |

| Satisfaction with care | SWC-EOLD | HCP | Baseline, quarterly, 2 mo postloss |

| AFDI | 2 mo postloss | ||

| Decision-making | DSI | HCP | Quarterly, 2 mo postloss |

| Health status | SF-12 | HCP | Baseline, quarterly, 2 and 7 mo postloss |

| Mood | K6 | HCP | Baseline, quarterly, 2 and 7 mo postloss |

| Complicated grief | ICG preloss | HCP | Baseline |

| ICG postloss | HCP | 2 and 7 mo postloss | |

Advance directives = do-not-resuscitate, do-not-intubate, do-not-hospitalize, no artificial hydration, antibitotics or tube-feeding, living will.

Interventions = feeding tubes, intravenous therapy, venipunctures, artificial ventilation, trunk or limb restraints, blood transfusions.

Sentinel events = new medical condition lead to a significant change in health status (eg, pneumonia, new eating problem, hip fracture, stroke, etc…).

Heath care utilization = hospitalizations, emergency room visits, intensive care admissions, hospice referral, involvement of physician extenders (nurse practitioners/physician assistants), visits by primary health care providers, special dementia care unit.

Nutritional status = hematocrit, albumin, body mass index, feeding problems, food intake at each meal.

Communication = time discussing advance directives with care provider, practitioner sought HCP opinion about goals of care, counseled HCP about expected health problems, explained comfort and life-prolonging care, and provided prognostic counseling.

Advance care planning = goals of care, understanding of the health problems in advanced dementia, perception that dementia is a terminal condition, estimated prognosis, any change in advance directives.

ADFI indicates After Death Family Interview; BANS-S, Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity; Braden, scale for assessing pressure ulcer risk; CAD-EOLD, The Comfort Assessment in Dying with Dementia; K6, psychological distress scale; QUALID, Quality of Life in Late-Stage Dementia; SF-12, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12 item; SM-EOLD, Symptom Management at the End-of-Life in Dementia; SWC-EOLD, Satisfaction with Care at the End-of-Life in Dementia; TSI, Test for Severe Impairment.

Resident Assessments

Resident data abstracted from the NH medical records included: demographic information, comorbid health conditions, medications, advance care planning, interventions, health care utilization, sentinel events, discomfort, and nutritional markers. Nurse interviews provided data regarding: functional status, physical comfort, and eating patterns. Direct clinical examination of the residents was used to assess cognition, and to obtain the anthropomorphic measures needed to calculate body mass index.

Demographic data included: age, sex, race, ethnicity, religious affiliation, education, primary language, marital status, length of NH stay, and prior living situation. All comorbid health conditions were identified at baseline. Daily medications were determined from the Medical Administration Record at each assessment. Detailed information was gathered regarding the specific administration of antibiotics, analgesics, and antipsychotic medications.

The following advance directives were ascertained at all assessments: do-not-resuscitate, do-not-hospitalize, do-not-intubate, and withholding feeding tubes, parenteral therapy, or antibiotics. The presence of a living will and the directives described within was also determined. Use of interventions included: feeding tubes, parenteral therapy, venipunctures, artificial ventilation, trunk or limb restraints, and blood transfusions.

Sentinel events, defined as new medical conditions that had the potential to lead to a significant change in health status and a shift in the goals of care (eg, pneumonia, hip fracture, etc.), occurring between follow- up assessments were identified and details regarding the management and outcome of these events were ascertained. The chart was also abstracted for the use of the following health services: hospitalizations, emergency room visits, intensive care admissions, hospice referrals, involvement of nurse practitioners and physician assistants, visits by primary care providers, and whether the resident resided in a special dementia care unit. To assess nutritional status, measures of body weight, serum albumin, and hematocrit recorded in the medical chart within 30 days of each assessment were obtained.

Physical comfort during the prior 90 days was measured by nursing interview using the Symptom Management at the End-of-Life in Dementia scale at baseline and all follow-up assessments.31 At the death assessment the Comfort Assessment in Dying with Dementia scale was used to describe symptoms during last 7 days of life.31 These scales were specifically designed to quantify physical discomfort in advanced dementia. The Quality of Life in Late-Stage Dementia was administered to nurses at all time periods to assess overall quality of life.32

Commonly used scales to measure functional status (eg, Katz ADL) are not sensitive to change in advanced disease. Therefore, the Bedford Alzheimer’s Nursing Severity-Subscale (BANS-S) (range 7 to 28; higher scores indicate more functional disability) was used to measure functional disability at all assessments.28 The Functional Assessment Staging (FAST) was also collected.33 The FAST consists of 7 major stages, with stage 7 representing the most advanced phase of dementia. Nurses also provided detailed information regarding feeding problems, oral intake at each meal, pressure ulcer risk (Braden Scale),34 and the existence of any pressure ulcers (categorized as stages 1 to 4).35

Cognitive assessments were conducted by direct clinical examination of the resident at each time period using the Test for Severe Impairment (range 0 to 24, lower scores indicate greater cognitive impairment),36 a validated and reliable measure of cognition in persons with advanced disability. As most residents were bedfast, knee height was used to estimate the resident’s height to calculate the body mass index.37

Finally, if the resident died, the primary and contributing causes of death recorded on the death certificate were ascertained. Death certificates were obtained from municipal offices if a copy was not in the resident’s chart.

HCP Interviews

Data gathered during the HCP interviews included: demographic information, advance care planning, communication, satisfaction with care, decision-making, health status, mood, and bereavement adjustment.

Demographic data included: age, sex, race, ethnicity, primary language, education, household income, religious affiliation, religiousity (importance of faith, frequency of religious services attendance), marital status, work status, relation to the resident, the number of years as HCP, and proximity of the HCPs’ primary residence to the NH.

At the baseline and each quarterly follow-up interview, HCPs were asked about the following advance care planning issues: primary goal of care (life-prolongation vs. comfort), their understanding of the health problems expected in advanced dementia, whether they perceived dementia as a terminal condition, and how close they believed the resident was to the end of life. HCPs were also asked whether the residents previously specified their care preferences to them (verbally or in a living will). At each quarterly follow-up, HCPs stated whether any of the residents’ advance directives (eg, DNR) had changed since the prior interview.

In terms of communication, HCPs were asked with whom (ie, physician, social worker) and for how long they discussed the residents’ advance directives at the time NH admission (baseline interview), and at the time of any changes (quarterly interviews). HCPs were also asked whether a NH physician did any of the following: sought the HCP’s opinion regarding goals of care, counseled the HCP about the expected health problems in advanced dementia, explained comfort and life-prolonging care, and provided prognostic counseling.

Satisfaction with overall end-of-life care was assessed at each time period using The Satisfaction with Care at the End-of-Life in Dementia Scale (SWCEOLD). 31 In addition, The After-Death Family Interview was administered at the 2 months postdeath interview. 27,30 The After-Death Family Interview specifically focused on care provided during the dying process in the following domains: physical comfort, shared decision-making, communication, treatment of the resident with respect, and tending to the emotional family needs.

Decision-making was assessed at each follow-up interview. HCPs were asked whether they had made any major health care decisions for the resident since the prior interview and if so, the nature of that decision (ie, pneumonia treatment, hospitalization, feeding problem). If HCPs’ had made a decision, their satisfaction with the decision-making process was measured using the Decision Satisfaction Inventory.38

The well-validated SF-1239 was used to measure the HCPs’ health status at each interview. In addition, HCPs were asked whether they experienced any hospitalizations, emergency room visits, or physician visits since the prior assessment. Mood was assessed with the K6, a 6-item instrument assessing symptoms of psychological distress used in the National Health Interview Survey, the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health (WMH) Initiative, and elsewhere.40

Finally, The Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG),41,42 was administered to HCPs 2 and 7 months after the residents’ death. The ICG assesses symptoms of complicated mourning (eg, separation and traumatic distress). A related instrument, the ICG-Short Form: Pre-loss was also administered to the HCP during the baseline interview to test the hypothesis that HCPs who have complicated grief before the residents’ death are more likely to experience this condition after their death.

RESULTS

The results presented below describe our experience implementing the CASCADE study protocol to date. A brief description of the baseline cohort is provided to illustrate the success of the recruitment scheme. Major challenges encountered during each component of the protocol and approaches to circumvent these challenges are presented. As data collection is on-going, findings related to the primary outcomes and specific aims of the study are forthcoming.

Study Facilities

To date, 51 facilities have been invited to participate in the study, of which 15 have been recruited. It is anticipated that at least 3 additional facilities will be recruited. A total of 36 facilities refused to participate for the following reasons: administrator would not respond to multiple telephone messages (N=21), senior management was in transition (ie, changing the director of nursing) (N=5), concern the study was too much work for sta. (N=6), and lack of interest (N=4). One recruited facility withdrew from the study citing that the staff was too busy. At the time of the withdrawal, all subjects recruited from that facility (N=4) had died and data collection was complete.

Facilities varied with respect to demographic features, ownership, staffing, and measures of quality. The mean number of beds in participant facilities was 185.5±(SD)155.8 (range, 62 to 700 beds), compared to a national average of 102.2±(SD)67.3 beds (Table 2). Similar to NHs nationwide, the majority of residents in the CASCADE facilities were female and white. The mean percentage of NHs with >85% Medicaid beds was 69.7%, comparable to the nationwide average of 61.4%. Slightly more than half (56%) the facilities had special care dementia units, 37.5% were for-profit, and 31.2% were part of a corporate chain. The staffing ratios were comparable to those nationwide. The mean number of pressure sores among high-risk residents was similar to average US NHs. However, study facilities displayed slightly better than average quality with respect to restraints use, indwelling foley catheter use, and deficiencies on state inspection.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of CASCADE Facilities vs. US Nursing Homes

| Characteristics | CASCADE Facilities (N = 15) | US Nursing Homes (N = 16,933) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| No. Beds | ||

| Mean ± SD | 185.2 ± 155.8 | 102.2 ± 67.3 |

| Range | ||

| % White residents | ||

| Mean ± SD | 83.1 ± 78.2 | 85.9 ± 79.8 |

| Range | 35.5–98.8 | |

| % Female residents | ||

| Mean ± SD | 75.6 ± 12.4 | 68.7 ± 10.7 |

| Range | 39.0–83.0 | |

| % Medicaid bed | 69.7 ± 9.7 | 61.4 ± 27.5 |

| Special care dementia unit (%) | 56% | 16.4% |

| Ownership | ||

| For profit (%) | 37.5 | 65.3 |

| Part of a chain (%) | 31.2 | 55.7 |

| Staffing* | ||

| Licensed nursing staff hours per resident per day | ||

| Mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.2 |

| Range | 0.8–1.9 | |

| Nursing assistant staff hours per resident per day | ||

| Mean ± SD | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 2.3 |

| Range | 1.7–3.2 | |

| Quality of Care*† | ||

| % High risk residents with pressure sores | ||

| Mean ± SD | 14.7 ± 4.5 | 14 |

| Range | 6–22 | |

| % residents with restraints | ||

| Mean ± SD | 4.5 ± 4.0 | 7 |

| Range | 0–13 | |

| % residents with indwelling foley catheters | ||

| Mean ± SD | 4.2 ± 3.4 | 6 |

| Range | 0–12 | |

| No. deficiencies on state inspection | ||

| Mean ± SD | 6.2 ± 5.0 | 8 |

| Range (0–41) | 0–16 | |

Means were not available for staffing and quality of care variables for all US nursing homes.

Quality of care data were unavailable at one CASCADE facility that was licensed as a chronic hospital.

Study Population

Upon screening the 15 participant facilities (total beds=2850), 919 residents had CPS scores of 5 or 6, representing approximately one-third of the entire population of the NHs. Among these 919 residents, 375 (40.8%) met all eligibility criteria. There were 32 eligible residents for whom consent was obtained, but who died before their baseline data could be collected. Among the remaining 343 eligible residents, 189 (55.1%) were recruited into the study. Reasons for nonrecruitment included HCP (N=153) and physician (N=1) refusal. Fifty-two of the HCPs who refused did not specify a reason. Reasons cited for refusal among the remaining 101 HCP nonparticipants included: lack of interest (N=53), study was too burdensome (N=30), privacy concerns (N=8), family illness (N=7), and topic was too painful (N=3). Nonrecruited eligible residents did not differ significantly from those recruited with respect to mean age or sex.

Median follow-up time for the resident cohort was 379 days. To date, 69 (36.5%) of recruited residents have died. However, as the study is on-going, the full 18-month follow-up period has not elapsed for many residents. Thus, the final mortality rate is expected to be higher by the study’s completion. Two residents were lost to follow-up after they moved to NHs that were not participating in the study. Only 9 HCPs were lost in follow-up; 8 refused to continue or could not be contacted and 1 died.

The recorded causes of dementia included: Alzheimer disease (N=130, 68.8%), multi-infarct dementia (N=35, 18.5%), and other causes (N=28, 14.8%) (4 residents had mixed Alzheimer and multi-infarct disease). The mean age of recruited residents was 84.8±(SD)7.9 years, 84.1% were female, and their ethnic/racial distribution was as follows: white, N=169 (89.5%); African American, N=18 (9.5%); and Hispanic, N=2 (1%). Recruited residents were severely cognitively impaired as indicated by a mean Test for Severe Impairment score of 0.5±(SD)1.3, with 75.7% scoring 0. Functional impairment was also advanced [mean BANS score=20.6±(SD)2.7]. FAST stage was 7 for 98% of the resident sample. Mean length of stay was 47.7±(SD)43.2 months.

The mean age of HCPs was 59.7±(SD)12.0 years, 61.4% were female and 90.5% were white. The HCPs’ relationship to the residents were as follows: child, N=131 (69.3%); spouse, N=23 (12.2%); niece or nephew, N=15 (7.9%); sibling, N=10 (5.3%); grandchild, N=2 (1.0%); legal guardian, N=2 (1.0%); and other, N=6 (3.3%). The distribution of the HCPs’ self-rated health was: excellent or very good, 59.3%; good, 25.9%; and fair or poor, 14.8%.

Data Collection

To date, data collection has involved: 189 baseline resident assessments and HCP interviews, 449 quarterly (follow-up) residents assessments, 432 quarterly HCP interviews, 68 resident death assessments, 53 two-month postdeath HCP interviews, and 36 seven-month postdeath HCP interviews. Approximately 2% of scheduled HCP interviews were not conducted because the HCP could not be contacted. All resident assessments have been obtained. There have been no adverse events arising from the study. At the end of each interview, HCPs were asked to rate their discomfort answering the questions. In only 48 of 712 (6.7%) completed interviews did the HCPs state that they were uncomfortable.

Approximately 1 hour was needed to complete the resident assessment (chart review, 45 min; nurse interview, 10 min; resident exam, 5 min). However, considerable additional time was spent traveling to the facility, locating the records, and tracking down the appropriate nurse to interview. HCP telephone interviews required approximately 10 minutes, with additional time spent coordinating the interview.

Factors Challenging and Enabling NH Recruitment

NH recruitment posed 2 major challenges (Table 3). First, there was the perception by administrators that the study would occupy too much staff time. In response, the project director emphasized the minimal effort required by facility staff during the very first contact with the administrator. The second major challenge represented frequent transitions in senior NH managers whose participation was essential to approve and conduct the study. To circumvent these upheavals, the project director was persistent in reapproaching a facility after a particular disruption had settled, sometimes waiting as long as 6 to 12 months after the initial contact. Factors that facilitated NH recruitment included approaching facilities known to have a successful track record conducting research, the established reputation of the Institute for Aging Research at Hebrew Senior Life, and the endorsement of NIH funding.

TABLE 3.

Major Factors Challenging and Enabling the Implementation of the CASCADE Protocol

| Protocol Component | Challenge | Strategy Employed to Circumvent Challenge | Enabling Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing Home Recruitment | Perception that study would occupy too much staff time |

Emphasize low staff burden during initial contact with administrator |

Established reputation of research team’s institution Federal funding |

| Major transitions or instability of nursing home management |

|

||

| Screening large nursing home populations for residents with advanced dementia |

|

|

|

| Subject Recruitment | Health Care Proxy refusal |

Use an experienced geriatric nurse researcher to recruit Emphasize low time commitment for health care proxy and low burden for residents |

|

| Enrollment of racial and ethnic minorities |

|

||

| Engaging busy nurses to interview |

Research assistants wear official nursing home identifcation badge Conduct staff in-services Leave study information and consent form in resident’s chart |

|

|

| Data Collection | Need to abstract data from multiple current and stored written sources |

Use computerized information (i.e., medications) whenever possible |

|

| Scheduling Health Care Proxy Interviews |

Conduct interviews at preferred times (i.e., evening, work) |

||

| Keeping track of follow-up assessments |

|

Factors Challenging and Enabling Subject Recruitment

The first challenge to subject recruitment involved efficiently screening entire NH populations for residents with advanced dementia (Table 3). Screening was facilitated by using computerized MDS data to obtain CPS scores. In the 5 NHs that did not have MDS databases, the RAs went unit-to-unit asking nursing staff to score the residents’ on the CPS. Although more onerous, this alternate screening process was feasible as it only involved responding to a single question related to the residents’ decision-making capability.

The second major hindrance to subject recruitment was the HCP refusal rate. To facilitate HCP consent, an information letter using stationary from the residents’ NH was mailed to the HCP before an initial telephone call. An experienced geriatric nurse researcher conducted all HCP recruitment, emphasizing the low time commitment of the study, that interviews would be conducted at the HCPs’ convenience, and that data collection presented almost no burden for the resident. The final recruitment challenge was adequate representation of minorities. Currently, efforts are focusing on recruiting additional facilities with higher proportion of ethnic and racial minorities.

Factors Challenging and Enabling Data Collection

Engaging busy staff nurses in the research interviews posed a challenge with regards to data collection. Although the interview required only 10 minutes, it remained difficult for over-burdened nurses to disengage from the many demanding tasks requiring their immediate attention. In addition, fluctuating work shifts and the greater use of agency nurses in some facilities, complicated the team’s ability to coordinate the interview with a nurse who had primary knowledge of the resident. To facilitate nursing participation, RAs avoided coming to the nursing unit at inconvenient times (ie, shift changes and medication passes), and occasionally calling ahead to make appointments with the nurses. The RAs also found it essential to obtain official identification badges from the facilities, to conduct structured in-services with the nursing sta., and to leave study information and consent forms in the residents’ charts. A second major data collection challenge involved the need to obtain information from multiple written sources such as current and past medical records (ie, many facilities split the charts every 3 months), medication administration records, and physician orders. This challenge was alleviated in one facility that had on-line medical records, but otherwise required perseverance by RAs. The most essential factor enabling data collection from NH staff and records was strong endorsement and involvement by a senior facility administrator.

Scheduling interviews was the main hindrance in collecting data from HCPs, particularly during popular vacation times. Strategies for facilitating data collection from HCPs included making an appointment for the next interview well in advance, and flexibility in conducting interviews at times preferred by individual HCPs (ie, evenings, at work).

Finally, timely completion of hundreds of resident assessments, HCP interviews and facility screenings, presented a challenge to the overall CASCADE protocol. To keep on task, a tracking program was created using ACCESS software which regularly provided RAs with individualized schedules of upcoming due dates for facility rescreening and data collection elements.

DISCUSSION

The experience of the CASCADE study as presented in this paper demonstrates our success conducting advanced dementia research in the NH setting. In particular, the study has shown that multiple, community NHs can be involved in a research protocol and that a cohort of NH residents with advanced dementia and their HCPs can be established and repeatedly assessed. Although this type of investigation presented specific challenges, the CASCADE experience helps elucidate strategies aimed at minimizing these challenges and factors enabling this research.

The CASCADE study corroborates that palliative care research is tolerated well by surrogates of persons will terminal illnesses,24,30,41–46 and extends this observation to proxies of NH residents dying with dementia. The CASCADE recruitment rate of approximately 50% of eligible subjects is similar to other investigations involving interviews of family members regarding the end-of-life experience of a loved one.24,30,42 Although eligible residents who were not enrolled in CASCADE did not differ from those enrolled with respect to age and sex, the degree to which their exclusion introduces bias into the study will need to be considered as the data are analyzed and interpreted.

The CASCADE recruitment protocol effectively identified NH residents with end-stage dementia as evidenced by the their severe cognitive impairment, advanced functional disability, and high mortality rate. The characteristics of the residents in CASCADE were similar to other advanced dementia cohorts with respect to mean age (reported range, 84 to 88 y),3,7,16,21,44–47 length of NH stay (reported mean, 40 mo),16 functional status,28,47 and cognitive disability.36 However, the CASCADE cohort had a comparatively higher proportion of female residents compared to these prior studies (CASCADE 84%, reported range, 57% to 76%).3,5,7,21,47,48 This finding may reflect the fact that CASCADE facilities had a relatively higher percentage of females than NHs across the US. Minority representation in CASCADE was equal to or greater than that reported in other advanced dementia studies,7,10,16 but below the NH population nationwide (19%).5 Given the importance of race/ethnicity in end-of-life care, ongoing recruitment efforts will target facilities with greater minority representation.

Prior research describing dementia caregivers has primarily been conducted in the community,43,44,49 rather than in the NH setting. Nonetheless, demographic characteristics of the HCPs enrolled in CASCADE are comparable to the few available reports describing proxies of the NH residents with advanced dementia such that their mean age is approximately 60 years,45,50 the majority are female,45,50 and roughly three-quarters are the resident’s child.6,45,50 In contrast, most dementia caregivers in the community are spouses.40,43 Emerging data suggest that the emotional distress of families does not decline when patients with dementia are institutionalized, 44 but the reason for this observation is not well understood. The extensive amount of data being collected in the CASCADE study will further our knowledge regarding the sources of burden borne by HCPs in the NH setting.

Facility characteristics are important determinants of end-of-life care.5,14,15 For example, facility factors associated with greater use of feeding tubes in advanced dementia include: larger NH size, for-profit ownership, greater proportion of non-whites, and lack of a special care dementia unit.5 The CASCADE facilities demonstrated variability with respect to demographic features, fiscal organization, staffing, and quality of care, such that the association of these factors with the experience of the residents with advanced dementia and their families can be examined in subsequent analyses.

The CASCADE study has some limitations that deserve comment. First, this is an observational study. Thus, although the study is designed to identify aspects of care in advance dementia that need improvement, it does not test any interventions. In the same vein, although the study will allow the comparison of outcomes resulting from different approaches to care (ie, antibiotics vs. comfort care for pneumonia), the results will be limited by the fact that it is not a randomized trial. Second, the study does not gather data from physicians regarding their perspectives of decision-making processes, communication with the family, and end-of-life care in advanced dementia. Finally, the study is limited to the Boston area, a predominantly white cohort, and facilities that had, on average, better quality of care indicators than NHs nationwide. Thus, some findings may not be generalizable to other geographic regions, non-white populations, and facilities of poorer quality.

Despite advances in understanding of the pathophysiology of dementia and the development of drugs that may temporarily improve symptoms, dementia remains a terminal condition. The clinical course and experience of NH residents with end-stage dementia has not been studied in a comprehensive and prospective fashion. This lack of information impedes our ability to provide the best care to the growing number of individuals dying with dementia and has been identified as a research priority.51,52 The data derived from the CASCADE study will help promote evidence-based clinical practices and health policies aimed at improving that care. This paper serves as methodologic reference for that work and supports future dementia palliative care research initiatives in the NH setting.

Acknowledgments

The investigators wish to thank the CASCADE study data collection and management team (Ruth Carroll, Cherie Swift, Sara VanValkenburg, Shirley Morris, Ellen Gornstein, Nina Shikhanov, and Margaret Bryan), all the staff at the participant nursing homes, and the residents and families who have generously given their time to this study.

Supported by NIH-NIA R01 AG024091 and P50 AG05134 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center Grant (S.L.M.).

References

- 1.Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, et al. Alzheimer’s disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 Census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1119–1122. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Miller SC, et al. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:321–326. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell SL, Morris JN, Park PS, et al. Terminal care for persons with advanced dementia in the nursing home and home care settings. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:808–816. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Roy J, et al. A national study of the clinical and organizational determinants of tube-feeding among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2003;290:73–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamberg JL, Person CJ, Kiely DK, et al. Decisions to hospitalize nursing home residents dying with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1396–1400. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrison RS, Siu AL. Survival in end-stage dementia following acute illness. JAMA. 2000;284:47–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahronheim JC, Morrison RS, Baskin SA, et al. Treatment of the dying in the acute care hospital: advanced dementia and metastatic cancer. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2094–2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meier DE, Ahronheim JC, Morris J, et al. High short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with advanced dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:594–599. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabiszewski KJ, Volicer B, Volicer L. Effect or antibiotic treatment on the outcome of fevers in institutionalized Alzheimer patients. JAMA. 1990;263:3168–3172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachs GA, Shega JW, Cox-Haley D. Barriers to excellent end-of-life care for patients with dementia. J Gen InternMed. 2004;19:1057–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovach CR, Wilson CR, Noonan PE. The effects of hospice interventions on behaviors, discomfort, and physical complications of end stage dementia nursing home residents. Am J Alzheimer Dis. 1996;11:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Gillick MR. Nursing home characteristics associated with tube-feeding in advanced cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:75–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gessert CE, Mosier MC, Brown EF, et al. Tube feeding in nursing home residents with severe and irreversible cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;48:1593–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Intrator O, Castle NG, Mor V. Facility characteristics associated with hospitalization of nursing home residents. Med Care. 1999;37:228–237. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medicare Nursing Home Compare. [Accessed December 1, 2005]; Available at: http://www.medicare.gov/NHCompare/Home.asp.

- 17.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M174–M182. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartmaier SL, Sloane PD, Guess HA, et al. Validation of the Minimum Data Set Cognitive Performance Scale: agreement with Mini-Mental State Examination. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50:M128–M133. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.2.m128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, De Leon MJ, et al. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris JN, Hawes C, Fries BE, et al. Designing the National Assessment Instrument for nursing homes. Gerontologist. 1990;30:293–307. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB, et al. Estimating prognosis for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA. 2004;291:2734–2740. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life: patients’ perspective. JAMA. 1999;281:163–168. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenger NS, Rosenfeld K. Quality indicators for end-of-life care in vulnerable elders. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:667–685. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_part_2-200110161-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cogen R, Patterson B, Chavin S, et al. Surrogate decision-maker preferences for medical care of severely demented nursing home patients. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:1885–1888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teno JM, Landrum K, Lynn J. Defining and measuring outcomes in end-stage dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teno JM, Clarrige B, Casey V, et al. Validation of the toolkit after death bereaved family member interview. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:752–22. 758. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Volicer l, Hurley AC, Lathi DC, et al. Measurement of severity in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M223–M226. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.m223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P. What is appropriate health care for endstage dementia? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb05943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of death. JAMA. 2004;291:83–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Volicer L, Hurley L, Blasi ZV. Scales for the evaluation of end-of-life care in dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15:194–2000. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiner MF, Martin-Cook K, Svetlik DA, et al. The quality of life in late-stage dementia (QUALID) scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2000;1:114–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reisberg B. Functional assessment staging (FAST) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1998;24:653–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergstrom N, Demuth PJ, Braden BJ. The Braden Scale for predicting pressure sore risk. Nurs Res. 1987;36:205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure ulcers: incidence, prevalence, cost and risk assessment. Consensus Development Conference Statement. Decubitus. 1989;6:42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albert M, Cohen C. The test for severe impairment: an instrument for the assessment of patients with severe cognitive dysfunction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:449–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muncie HL, Sobal J, Hoopes M, et al. A practical method of estimating stature of bedridden female nursing home patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35:285–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1987.tb04632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barry MJ, Cherkin DC, YuChiao C, et al. A randomized trial of a multimedia shared decision-making program for men facing a treatment decision for benign prostatic hypertrophy. Dis Manage Clin Outcomes. 1997;1:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. A 12-item short form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary test of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Newsom J, et al. The Inventory of Complicated Grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59:65–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prigerson HG, Cherlin E, Chen JH, et al. The Stressful Caregiving Adult Reactions to Experiences of Dying (SCARED) Scale: a measure for assessing caregiver exposure to distress in terminal care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:309–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schulz R, Mendelsohn AB, Haley WE, et al. End-of-life care and the effects of bereavement on family caregivers of persons with dementia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1936–1942. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schulz R, Belle SH, Czaja SJ, et al. Long-term care placement of dementia patients and caregiver health and well-being. JAMA. 2004;292:961–967. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitchell SL, Lawson FME, Berkowitz RA, et al. A cross national survey of decision for long-term tube-feeding in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:391–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanson L, Danis M, Garrett J. What is wrong with end of life care? Opinions of bereaved family members. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:1339–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Steen JT, Kruse RL, Ooms ME, et al. Treatment of nursing home residents with dementia and lower respiratory tract infection in the United States and the Netherlands: an ocean apart. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:691–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schonwetter RS, Han B, Small BJ, et al. Predictors of survival among patients with dementia: an evaluation of hospice Medicare guidelines. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20:105–113. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins C, Ogle K. Patterns of predeath service use by dementia patients with a family caregiver. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:719–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sloane PD, Zimmerman S, Hanson L, et al. End-of-life care in assisted living and related residential care settings: comparison with nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1587–1594. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kayser-Jones J. The experience of dying: an ethnographic NH study. Gerontologist. 2002;42:11–19. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Institutes of Health. State-of-Science Conference Statement: Improving End-of-Life Care. [Accessed January 31, 2006];2005 Available at: http://consensus.nih.gov/PREVIOUSSTATEMENTS.htm#EndOfLifeCare.