Abstract

Involving caregivers in hospice interdisciplinary team (IDT) meetings has been offered as a potential solution to caregivers' unmet communication needs. This case study details one caregiver's participation in her mother's hospice interdisciplinary team care planning meetings, both in person and via videophone technology. This preliminary case is offered as part of a larger National Cancer Institute sponsored study investigating involvement of caregivers in team meetings using videophone technology. This analysis highlights communication differences between the two mediums as well as measures caregiver outcomes. Findings noted differences in team leadership and verbal validation and remediation between the two mediums. Caregiver outcomes revealed potential benefits of their involvement in team meetings. Caregiver-team communication issues are noted including the need for standardized caregiver assessment and team education and training.

Keywords: caregiver, interdisciplinary team, videophone technology, communication

Hospice caregivers report anxiety about patient care, uncertainty regarding treatment, role changes within family, transportation needs, strained financial resources, physical restrictions, lack of social support, and loneliness (1). The most challenging aspect of the caregiver role is inadequate health professional support (1). Specifically, caregivers report an increased need for more information, communication, and services and support from community services (1-3). The inclusion of patients and families in interdisciplinary team (IDT) meetings is theorized to improve communication and satisfaction with care (4). However, challenges to patient and family participation include organizational context, structural concerns such as team comfort and communication, and patient/caregiver burdens (5).

Finding ways to overcome the challenges and support the involvement of caregivers in IDT meetings is important to assure hospice goals and plans of care are centered on both the patient and the family (4). While preliminary research on hospice IDT meetings has revealed that interdisciplinary collaboration does not always occur (6, 7), caregiver involvement has been theorized as a way to improve this process and change the way that IDT meetings are conducted (4). This paper reports on one case study within a larger project which seeks to use videophone technology to support the involvement of patients and caregivers in the IDT meetings. Currently, caregiver involvement in hospice IDT is not a standard of care (4) and no research exists exploring the differences between videophone and face-to-face communication between hospice teams and caregivers. The purpose of the case study presented here is to (1) explore team communication with caregivers, and (2) to assess care outcomes over the trajectory of the caregiver's participation in the interdisciplinary team process.

Method

Participants were recruited from a hospice agency in the Midwestern United States. Hospice staff, patients, and caregivers were consented for participation in a larger intervention study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the supporting university. The case called for an in-depth analysis as it is the only one so far within the larger project where the caregiver was able to participate in both a face-to-face and video-mediated IDT meetings.

Hospice staff provided referrals to a Graduate Research Assistant (GRA) who then contacted patients and caregivers for consent. Upon consent, baseline measures were taken and a videophone that operates over regular phone lines was installed in the caregiver's home. Caregivers used the videophone to call in and participate in IDT meetings. In this case study, three videophone calls and one face-to-face meeting occurred between the caregiver and the hospice team. The face-to-face meeting was unplanned as the caregiver “showed up” at the office unexpectedly for the scheduled videophone contact with the IDT. All videophone communication and the one time face-to-face encounter were videotaped and conversations were transcribed word for word. A grounded theory approach (8) was used to review the transcripts. A constant comparative method of the transcripts in relation to the two communication mediums was conducted (9). Once thematized, the data were circulated among members of the research team to check for validity.

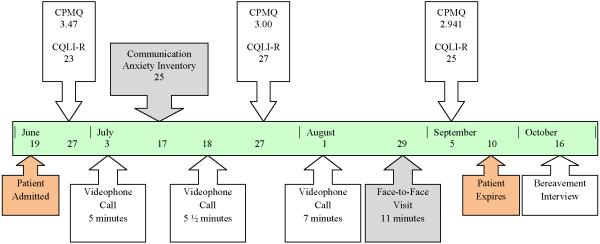

Three instruments were used to measure caregiver outcomes. The Caregiver Quality of Life Index Revised (CQLI-R) was used to measure caregivers' quality of life (10). The Caregiver Pain Management Questionnaire (CPMQ) (11) was used to measure caregiver concerns about pain management (11). The Communication Anxiety Inventory-Form State (12) was used to assess actual responses of fear or anxiety during the videophone experience. The GRA contacted caregivers every 30 days to repeat the measures. Additionally, the GRA conducted a bereavement interview 30 days after the patient expired. Please see Figure 1 for an overview of the caregiver's participation and the measures.

Figure 1.

Timeline of Caregiver Participation and Clinical Care Measures.

Results

One Caucasian female caregiver, Mrs. Bee (name changed), participated in the study for 77 days. The patient, her mother, was living in a long term care facility. Mrs. Bee was married and had no other care-giving responsibilities. She lived 1.5 miles away from the long term care facility, had no outside employment, and had a high school education. Mrs. Bee participated in three videophone calls with the IDT and one face-to-face encounter. The three video meetings were 5, 5 ½, and 7 minutes, while the face-to-face meeting lasted 11 minutes.

A total of three repeated measures using the CQLI-R and the CPMQ were taken. Mrs. Bee's initial assessment on the CPMQ yielded an average score of 3.47 which demonstrates mild overall concern, but time two (3.00) and time three measures (2.941) indicate more concern. Repeated measures on the CQLI-R over the duration of the study show a positive trend on the caregiver's quality of life as the overall CQLI-R score moves from 23 to 27 on a 40 point scale (0 is lowest quality of life and 40 is the highest quality of life). Finally, Mrs. Bee's score of 25 on the Communication Anxiety Inventory suggest low anxiety and fear affiliated with use of the videophone technology.

Two distinct communication differences were noted between videophone conferences and the face-to-face interaction. First, there was an obvious and apparent shift in the leadership of the meeting. In videophone communication the direction and content of the conversation was directed by the caregiver. For example, in the first and third videophone calls Mrs. Bee was asked to provide an update on the condition of her mother. Although the second videophone call began with team introductions, Mrs. Bee interrupted the introduction process and began addressing questions to the case managing nurse. In the face-to-face interaction, however, the team provided the leadership and direction of the meeting. The nurse began to provide the caregiver with an update on her mother. Throughout the entire face-to-face meeting, the discussion was dictated by the team rather than the caregiver.

Second, videophone communication and face-to-face interaction differed in validation and remediation. Validation and remediation of the caregiver's concerns did not occur in videophone communication. In the videophone calls Mrs. Bee expressed concern about the use of morphine, however the concern was minimized by the team and a plan of action never addressed. As a result her concern was never validated and the responsibility of remediation was also placed upon the caregiver. There was no attempt to educate Mrs. Bee on morphine in terminally ill individuals, or to teach Mrs. Bee how she might assess overmedication herself.

Validation and remediation did occur in the face-to-face interaction. When the caregiver interjected her concern about the use of a catheter, the nurse asked the caregiver to elaborate on her concern. Once the caregiver explained the reason behind her concern, both the doctor and nurse responded thoroughly. The concern was validated when the nurse asked for an explanation of the concern. Overall, more than one team member verbally expressed interest in her comments and asked follow-up questions along with supportive statements.

In the bereavement interview Mrs. Bee said she found the videophone to be helpful. Additionally she stated that she was dissatisfied with hospice services and expressed great regret about her interaction with the team. She felt uninformed by hospice and felt that she was not informed when decisions were made. She also complained of not knowing the team and did not feel the support that she had hoped for from hospice.

Discussion

The case study presented here found that videophone communication afforded the caregiver more leadership in dictating the topic of discussion, yet the caregiver was given more verbal validation and remediation in the face-to-face interaction. Additionally, the caregiver's score on the CQLI-R indicated that involvement was positive, however, the CPMQ and the caregiver's qualitative comments in the bereavement interview demonstrate a communication breakdown despite caregiver participation.

Findings from this case study illustrate the need to incorporate standardized caregiver assessment as part of the IDT meeting. Our findings indicate that the team needs to have the skills and processes in place to address caregivers' feedback and accordingly improve or redesign the services delivered to patients and caregivers. Our results validate the need for routine caregiver inclusion and demonstrate that the CPMQ is a potential standardized measure that captures the perspective of hospice caregivers.

Communication differences between the two mediums suggest a larger inherent problem to caregiver involvement in IDT meetings. Changes in leadership and validation and remediation could be a result of the team's opinion and attitude toward including caregivers in the meeting. These differences may indicate that caregiver involvement was considered an intrusion into the team's typical meeting. This case study highlights the need to educate staff about how to include caregivers in the IDT meeting, particularly when using videophone technology.

While findings cannot be generalized, this case study informs future research on hospice interdisciplinary team communication with caregivers. Specifically, this case study demonstrates the need for: (1) caregiver inclusion in IDT meetings as an opportunity to ask questions of all team members, (2) the necessity of educating the team on effective communication, the assessment of caregivers, and on a paradigm shift that includes the caregiver as a recipient of hospice services, (3) and the need for caregiver education related to pain management.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute R21 CA120179: Patient and family participation in hospice interdisciplinary teams, Debra Parker Oliver, PI.

References

- 1.Aoun SM, Kristjanson LJ, Currow DC, Hudson PL. Caregiving for the terminally ill: at what cost? Palliat Med. 2005 Oct;19(7):551–5. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm1053oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hwang SS, Chang VT, Alejandro Y, Osenenko P, Davis C, Cogswell J, et al. Caregiver unmet needs, burden, and satisfaction in symptomatic advanced cancer patients at a Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center. Palliat Support Care. 2003 Dec;1(4):319–29. doi: 10.1017/s1478951503030475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans WG, Cutson TM, Steinhauser KE, Tulsky JA. Is there no place like home? Caregivers recall reasons for and experience upon transfer from home hospice to inpatient facilities. J Palliat Med. 2006 Feb;9(1):100–10. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliver DP, Demiris G, Wittenberg-Lyles E. The promise of videophone technology for patient and family participation in hospice interdisciplinary team meetings. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. In Review. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker Oliver D, Porock D, Demiris G, Courtney K. Patient and family involvement in hospice interdisciplinary teams. J Palliat Care. 2005 Winter;21(4):270–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bokhour BG. Communication in interdisciplinary team meetings: what are we talking about? J Interprof Care. 2006 Aug;20(4):349–63. doi: 10.1080/13561820600727205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wittenberg-Lyles EM. Information sharing in interdisciplinary team meetings: an evaluation of hospice goals. Qual Health Res. 2005 Dec;15(10):1377–91. doi: 10.1177/1049732305282857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine; Chicago: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffey A, Atkinson P. Making sense of qualitative data analysis: complementary strategies. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courtney K, Demiris G, Oliver DP, Porock D. Conversion of the Caregiver Quality of Life Index to an interview instrument. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2005 Dec;14(5):463–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Letizia M, Creech S, Norton E, Shanahan M, Hedges L. Barriers to caregiver administration of pain medication in hospice care. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2004;27(2):114–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Booth-Butterfield S, Gould M. The communication anxiety inventory: Validation of state- and context- communication apprehension. Communication Quarterly. 1986;34:194–205. [Google Scholar]