Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the relationship between smoking and trauma exposure in a population-based, longitudinal sample. Contrary to current smoking trends in the general population, recent findings indicate continued high smoking rates in trauma-exposed samples.

Methods

A nationally representative sample of 15,197 adolescents was followed from 1995 (mean age=15.6) to 2002 (mean age=22) as part of 3 waves of The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). We examined the relation between self-reported trauma exposure and smoking behaviors (lifetime regular, current regular), nicotine dependence (Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND)), number of cigarettes per day, and age of onset of regular smoking.

Results

Controlling for demographics and depressive symptoms, exposure to traumatic events yielded a significant increase in the odds of lifetime regular smoking. Nicotine dependence and cigarettes smoked per day was also significantly related to exposure to Childhood Physical and Sexual Abuse. Decreased age of regular smoking onset was seen for those reporting Childhood Physical Abuse and Childhood Sexual Abuse.

Conclusions

Exposure to traumatic life events during childhood and young adulthood increases the risk of smoking, highlighting the need to prevent and treat tobacco use in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Traumatic Stress, Smoking, Nicotine Dependence, Adolescent, Depression

INTRODUCTION

Despite a decrease in smoking prevalence in the general population [1], smoking prevalence has remained high among individuals with a psychiatric disorder [2]. Clinical and epidemiological studies have demonstrated that, relative to those without a mental health condition, there is a strong association between psychiatric conditions, symptoms, and increased smoking prevalence [2, 3]. This relationship extends to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In both clinical and epidemiologic studies of individuals with PTSD, the rates of current cigarette smoking and nicotine dependence have been shown to be three times higher than those in the general population [4-7].

Although a diagnosis of clinical PTSD may be sufficient to increase the risk of smoking, it may not be necessary. A small number of studies have found an increased risk of smoking and nicotine dependence among individuals who report exposure to trauma or adverse events independent of a clinical diagnosis of PTSD [5, 8, 9]. For instance, in a large sample of German adults Hapke et al. (2005) found that persons with PTSD had the highest rates of smoking (OR: 2.12; 95% CI: 1.16 - 3.90), but trauma exposure independent of PTSD was also statistically significantly associated with smoking (OR: 1.28; 95% CI: 1.09 - 1.51). This relationship between trauma exposure and substance use may be particularly unique to smoking as Breslau et al (2003) observed a relation between trauma exposure and 10-year cumulative incidence of nicotine dependence, but found no relation between trauma exposure and alcohol use. Thus, exposure to a traumatic event, defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) as experiencing, witnessing, or being confronted with an event(s) that involve actual or threatened death, serious injury, or threat to the physical integrity of self or others [10], may be a sufficient risk factor for smoking or other smoking-related outcomes (e.g., nicotine dependence). Since, only a small proportion of trauma-exposed individuals develop lifetime PTSD (7%) [11], identifying those with trauma exposure rather than PTSD per se may be an important public health strategy in identifying those at risk for smoking.

Depressive symptoms commonly co-occur among those who have been exposed to a traumatic life event and/or have PTSD [12, 13]. Depressive symptoms also demonstrate a strong relationship with smoking behavior and nicotine dependence [13, 14]. However, the potential confound of depression has been accounted for in a limited number of studies on trauma exposure and smoking [15].

To date, studies examining the relationship between trauma exposure and smoking have focused primarily on clinical or high risk populations [4, 6]. Studies have not examined the relationship that trauma during adolescence has to young adult smoking. Since this is an age when smoking behaviors often starts, it is important to evaluate this potential association. In the present study we assessed the association between self-reported exposure to various traumatic life events and risk of regular smoking. Second, we examined the relationship between trauma exposure and indicators of smoking severity among individuals who were current smokers. In multivariate analyses, we accounted for the potential confounding effects of self-reported depressive symptoms and other potential confounds (e.g., age, race, sex, highest level of education among parents, and parental smoking). To undertake these study goals, we examined data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a nationally representative sample of adolescents followed into young adulthood [16].

METHODS

Data Source

The study sample was drawn from 20,747 adolescents from the Add Health, a nationally representative study of adolescents. Using an IRB-approved protocol, respondents participated in surveys on three separate waves: in 1995 (Wave 1; mean age=15.6, SD=1.7); 1996 (Wave 2; mean age=16.2, SD=1.6); and August 2001 to August 2002 (Wave 3; Mean age=22, SD=1.8). The Wave 3 cross-sectional cohort includes 15,197 respondents. By design, the Add Health survey included a sample stratified by region; urbanicity; ethnicity; and school type and size to garner a nationally representative sample. Details regarding the design and data collection are described elsewhere [16].

Sample

For the present study, we examined data from the most recent wave (Wave 3) of data collection. However, data from parental interviews that were conducted at Wave 1 that involved self-report of parental education level and smoking status were also used. Analyses excluded individuals whose post-stratification weights were unavailable (n=875) and pregnant women (n=379), as women who were pregnant may alter or discontinue their smoking behaviors [17]. The Wave 3 sample used for these analyses was partitioned to correspond with the reports of items assessing trauma exposure and smoking. One sample includes those who reported exposure to traumatic life events in the past year and ever vs. never smoking in the past year (n = 7,436). The other sample includes those who reported exposure to a traumatic event in childhood and smoking onset subsequent to that event (n = 11,394). Reduction in these sample sizes for multivariate models was a result of listwise deletion.

Measures

Smoking Status

Initially, participants were classified into groups based on their self-reports of ever-regular smoking (having ever smoked at least one cigarette every day for 30 days). To correspond with the time-frame of reported trauma (see below) the sample of participants was classified into two different categories: 1) “Ever-Regular Smoking in Past Year” vs. “Never-Regular Smoking in Past Year” and 2) “Ever-Regular Smoking After 6th Grade” vs. “Never-Regular Smoking After 6th Grade”. In the initial case (smoking in past year), individuals who began smoking prior to a year before their Wave 3 interview did not contribute to the analyses. In the subsequent case (smoking after 6th grade) individuals who began smoking prior to age 11 (a proxy for 6th grade) did not contribute to the analyses. For both cases, the “Never-Regular Smoker” group was comprised of individuals who had never tried smoking, had only taken one or two puffs, who had taken puffs but never smoked an entire cigarette, or who had smoked an entire cigarette but never smoked regularly. Smoking behavior has been quantified in a similar manner in other epidemiological studies [18, 19].

Among respondents currently smoking at Wave 3, two additional smoking behaviors were utilized: 1) the number of cigarettes smoked/day in the last 30 days (1 - 100 cigarettes); and 2) self-report of nicotine dependence. Self report of nicotine dependence was measured using the Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence, a widely used six item measure of nicotine use [20]. Scores from this instrument have been found to be correlated with biomarkers for nicotine levels [21]. Summed scores from these six items were used as the primary measure of nicotine dependence for the analysis. In addition, the age of regular smoking onset was examined for those participants who reported exposure to early childhood traumatic life events.

Trauma exposure

In Wave 3, participants were asked to retrospectively report on the exposure to various trauma types: Unwanted Sexual Contact, Physical Assault, Interpersonal Violence, Childhood Sexual Abuse, and Childhood Physical Abuse. To quantify “Unwanted Sexual Contact” and “Interpersonal Violence” participants were asked to report on whether or not these types of trauma occurred in any of their relationships within the past year and the number of times it occurred. Individuals who did not have any relationships in the past year or who indicated no instances of unwanted sexual contact or interpersonal violence were coded as 0 and were the referent group. If an individual reported having more than one relationship in the past year their score reflected occurrence across any of their relationships in the past year. The Unwanted Sexual Contact item asked “how often has your partner insisted on or made you have sexual relations with him/her when you didn't want to.” The low prevalence of multiple occurrences of this type trauma prevented the creation of an ordinal variable and thus a dichotomous variable was used. The “Interpersonal Violence” variable utilized items and the scoring procedure from the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) [22]. Items inquiring about being threatened with violence in a relationship were aggregated (e.g., have you been: 1) pushed or shoved, hit, slapped, kicked; 2) injured; 3) threatened with violence). Since this was more frequent in the sample the variable was coded as both a dichotomous exposure variable and ordinal variable reflecting the number of times (1 to 2 times; 3 to 5 times; and 6 or more times). This approach allowed for evaluating the relationship between increasing exposure to interpersonal violence on smoking.

Physical Assault was comprised of items asking whether the participant ever 1) witnessed violence such as a shooting or stabbing, or having a friend or family member commit suicide; 2) was threatened with a gun or knife; or 3) physically attacked, which included being shot or stabbed, and being robbed or physically assaulted. This variable was coded as a dichotomous variable (presence or absence of any three assault types) and an ordinal variable which included being exposed to one of the three types or 2 or 3 of the 3 types. As with relationship violence, this approach allowed for evaluating the relationship between cumulative exposures to violent assault on smoking.

Additional trauma variables included the following: “Childhood Physical Abuse” (CPA) defined as being slapped, hit, kicked or neglected by a caregiver and “Childhood Sexual Abuse” (CSA) defined as being forced to engage in sexual relations with an adult caregiver. For these types of trauma participants were asked to report on the number of times these two types of traumatic events occurred prior to the 6th grade.

Depressive Symptoms

The Add Health study included a modified 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies - Depression (CES-D). For Add Health, the response scale and tense (i.e., from the first to second person) of some CES-D items were modified, but have been shown to not meaningfully affect the internal structure of the measure [23]. This version of the CES-D has demonstrated good internal consistency across waves (Cronbach's α=. 87 at Wave 3).

Demographic variables

Factors related to socioeconomic status (SES) have also been shown to be associated with the development of smoking [24], thus we controlled for parental report of the highest education level. Additional demographic variables included age, race, sex, and parental smoking. These variables were included as they have been shown to be related to smoking behaviors in previous studies [25].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS-callable SUDAAN (version 8.0) statistical software [26]. SUDAAN allows for control of survey design effects of individuals clustered in sampling unit by school, and stratification of geographic region. Post-stratification weights were applied in order to allow the results to be comparable to young adults in the U.S. population.

For the trauma exposure variables that inquired about occurrences in the past year (i.e., unwanted sexual contact, physical assault, and interpersonal violence), the analyses were limited to participants who reported smoking onset in the past year. It was believed that this would most accurately capture exposure to trauma and smoking relationship within the same timeframe (e.g., Wave 3). Ever-Regular smoking after 11 years of age (a proxy for 6th grade) was used to determine the relationship between CSA and CPA that occurred prior to 6th grade and risk of smoking. The percentage of smoking by trauma type was initially calculated. This was followed by multiple logistic regression analyses to examine the relationship between trauma exposure and Ever-Regular smoking status (with Never-Regular Smoking as the referent) controlling for age, race, sex, highest level of education among parents, depressive symptoms, and parental smoking. Examination of the ordinal trauma variables and smoking status was used to evaluate the incremental contribution of repeated trauma exposure. Among respondents currently smoking at Wave 3, t-tests were used to test the difference in mean nicotine dependence and number of cigarettes smoked per day between those who reported exposure to trauma vs. those with no history of reported trauma. T-tests were also used to determine the relationship between exposure to CSA and CPA, and Age of Onset of Smoking.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic information is shown in Table 1. Among smokers in the past year, the sample reported regular smoking onset at age 19.84 (SE =.18) (not shown). Among the sample of ever-regular smoking after sixth grade, the mean age of regular smoking onset was 16.59 (SE=.05) (not shown). Among the sociodemographic variables, ethnicity and depressive symptoms (as measured by the CES-D) were significantly related to both smoking phonotypes (i.e., Ever-Regular Smokers in the past year and Ever-Regular Smokers after Sixth Grade). Table 2 and 3 shows the prevalence of various trauma types and Ever-Regular smoking. The percentage of Ever-Regular Smokers for the sample at Wave 3 was 38.6%, which is consistent with prevalence data from other sources [27]. Among those who reported exposure to trauma in the past year, the overall percentage of Ever-Regular Smokers was 59.78% (not shown). The most frequently reported traumatic events included CPA (32% for any occurrence, 14% for 1-2 occurrences, 19% for greater than 2 occurrences) and Interpersonal Violence (24% for any occurrence, 10% for 1-2 occurrences, and 13% for greater than 2 occurrences). These estimates correspond to the results from at least one other regionally representative sample [28].

Table 1.

Demographics and other variables of ever and never smokers within the past year and after 6th grade

| Demographics | Ever-Regular Smoking in Past Year, No (%) |

Ever Regular Smoking after 6th grade |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Ever | X2 | Never | Ever | X2 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 3584 (94.63) | 169 (5.37) | X2 = 0.27 | 3537 (57.41) | 2246 (42.60) | X2 = 0.64 |

| Female | 3514 (94.18) | 169 (5.82) | 3473 (58.42) | 2138 (41.58) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 4157 (93.81) | 225 (6.19) | X2 = 5.22* | 4103 (53.26) | 3383 (46.74) | X2 = 74.31* |

| non-White | 2936 (95.93) | 112 (4.07) | 2904 (72.85) | 1003 (27.15) | ||

| Parental education | ||||||

| <High School | 778 (96.53) | 26 (3.47) | X2 = 5.93 | 764 (63.21) | 373 (36.79) | X2 = 26.30* |

| High School or GED | 1360 (93.42) | 74 (6.58) | 1343 (54.34) | 1037 (45.66) | ||

| A.A. or Some College | 1759 (94.01) | 92 (5.99) | 1739 (54.39) | 1255 (45.61) | ||

| College Degree or greater | 2234 (93.92) | 120 (6.08) | 2210 (61.73) | 1208 (38.27) | ||

| Parental Smoking | ||||||

| No | 4954 (94.15) | 255 (5.85) | X2 = 1.58 | 2133 (70.72) | 775 (29.28) | X2 = 129.40* |

| Yes | 2158 (95.08) | 83 (4.92) | 4891 (53.87) | 3614 (46.13) | ||

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | OR (95% CI) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | 21.84 (.12) | 20.52 (.17) | 1.52 (1.67, 1.37) | 21.84 (.12) | 20.54 (.17) | .99 (.94, 1.03) |

| Depressive Symptoms | 5.23 (.09) | 6.07 (.26) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.07) | 4.15 (.09) | 6.05 (.27) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.04) |

Note. Percents and means are weighted to be representative of the U.S. population of young adults; A.A. = Advanced Associates Degree; GED = General Equivalent Degree;

p < .05

Table 2.

Percent and adjusted odds ratio* of onset of ever-regular smoking in past year by trauma exposure in past year

| Prevalence of Trauma |

Ever-Regular Smoking in Past Year** |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category of Trauma | % |

% |

Odds Ratio (95% CI)* |

p value |

| Unwanted Sexual | n = 5164 | |||

| Contact | ||||

| None | 89.7 | 5.9 | 1 | referent |

| 1 or more | 10.3 | 6.6 | 1.06 (.68,1.66) | ns |

| Physical Assault | n = 6360 | |||

| None | 90.3 | 4.9 | 1 | referent |

| 1 or more | 9.67 | 9.9 | 1.91 (1.25, 2.92) | 0.003 |

| None | 90.3 | 4.9 | 1 | referent |

| 1 of 3 Types | 7.43 | 10.2 | 1.97 (1.25, 3.10) | 0.004 |

| 2 - 3 Types | 2.23 | 8.9 | 1.70 (.77, 3.76) | ns |

| Interpersonal Violence | n = 5152 | |||

| None | 78.4 | 5.7 | 1 | referent |

| 1 or more | 21.6 | 6.9 | 1.46 (1.01, 1.07) | 0.04 |

| None | 78.4 | 5.7 | 1 | referent |

| 1 to 2 times | 9.68 | 4.8 | 1.05 (.63, 1.73) | ns |

| 3 to 5 times | 4.16 | 5.7 | 1.08 (.50, 2.37) | ns |

| greater than 6 times | 7.75 | 10.0 | 2.28 (1.34, 3.88) | 0.003 |

Models adjusted for age, ethnicity/race, sex, highest level of education among parents, depressive symptoms, and parental smoking

To correspond with exposure variable individuals who began smoking prior to a year before their Wave III interview did not contribute to the outcome

Table 3.

Percent and adjusted odds ratio of onset of lifetime ever-regular smoking by childhood sexual and physical abuse

| Prevalence of Trauma |

Ever-Regular Smoking After 6th Grade |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category of Trauma | % | % |

Odds Ratio (95% CI)* |

p value |

| CSA b/f 6th grade | n = 9551 | |||

| None | 95.5 | 41 | 1 | referent |

| Yes | 4.5 | 48.3 | 1.43 (1.07,1.92) | 0.02 |

| None | 95.5 | 41 | 1 | referent |

| 1 to 2 times | 2.93 | 50.3 | 1.61 (1.10,2.34) | 0.01 |

| 3 to 5 times | 0.78 | 40 | .99 (.48,2.02) | ns |

| Greater than 6 times | 0.79 | 49 | 1.36 (0.74,2.48) | ns |

| CPA b/f 6th grade | n = 9286 | |||

| None | 67.69 | 39.3 | 1 | referent |

| Yes | 32.31 | 45.4 | 1.28 (1.13,1.45) | 0.0001 |

| None | 67.69 | 39.3 | 1 | referent |

| 1 to 2 times | 13.74 | 44 | 1.15 (.99,1.35) | ns |

| 3 to 5 times | 7.18 | 44.3 | 1.40 (1.11,1.78) | 0.005 |

| greater than 6 times | 11.39 | 48 | 1.37 (1.12,1.69) | 0.002 |

Models adjusted for age, race, sex, highest level of education among parents, depressive symptoms, and parental smoking

** To correspond with exposure variables, individuals who began smoking prior to the 11 years of age (approximately 6th grade) did not contribute to the outcome

The results of multivariate analyses can be seen in Table 2 and Table 3. In each case, tests of the full model versus a model with intercept only were statistically significant. No statistically significant linear trend was seen between the number of traumatic events and smoking for any category of trauma. Those exposed to the highest number of incidents of interpersonal violence (greater than 6 times) had the highest odds of smoking. In addition, individuals with at least 1 exposure to physical assault were also at increased risk for smoking. However, greater levels of physical assault were not statistically significantly associated with ever-regular smoking. In each of the logistic regression models, depressive symptoms and ethnicity yielded a significant effect (not shown). Thus, the association between trauma exposure and smoking represents the association between these variables controlling for depressive symptoms and race/ethnicity. Interaction effects between depressive symptoms and trauma exposure variables were examined in all models and all were non-significant (not shown).

To evaluate the relative contribution of trauma categories on smoking, a full model with all trauma categories was tested against a constant-only model with nuisance variables. In estimating ever-regular smoking in past year, a comparisons of log-likliehood ratios indicated a significant improvement in fit when adding interpersonal violence to a model with physical assault [X 2 (1) = 419.44, p < .001], but adding unwanted sexual contact to a model with both physical assault interpersonal violence did not significantly improve overall model fit [X 2 (1) = 1.42, p = .23]. In the model with both interpersonal violence and physical assault entered simultaneously, the odds ratios for both variables decreased (physical assault OR = 1.77; 95% CI: 1.16, 2.70; Interpersonal violence OR = 1.39; 95% CI: .96 - 2.02). This pattern of findings suggests that interpersonal violence and physical assault have shared variance and that physical assault appears to be a reliable predictor of ever-regular smoking after accounting for interpersonal violence. Unwanted sexual contact does not appear to be reliable predictor of ever-regular smoking after controlling for physical assault and interpersonal violence. In estimating ever-regular smoking since 6th grade, the log-likliehood ratios test indicated a significant improvement in fit when adding CPA to a model including CSA and nuisance variables [X 2 (1) = 465.28, p < .001]. When entered simultaneously, the odds ratios for both variables decreased (CSA OR = 1.29; 95% CI: .93 - 1.77; CPA OR = 1.24; 95% CI: 1.09-1.41). This pattern suggests that both CPA and CSA have shared variance, and that CPA appears to be a reliable predictor or ever-regular smoking even after accounting for a history of CSA.

The bivariate relationships between the various trauma exposure variables and both nicotine dependence, and number of cigarettes smoked per day can be seen in Table 4. The number of cigarettes smoked per day was significantly related to CPA and CSA. Of all the types of trauma, those exposed to 1 to 2 occurrences of CSA reported the greatest mean number of cigarettes smoked per day (M=15.00, SE=1.15). Similarly, those reporting a history of multiple incidence of CPA reported smoking nearly 13 cigarettes per day which was statistically significantly different from those with no history of CPA. A number of trauma types were significantly related to greater self-reported nicotine dependence. The greatest mean nicotine dependence was reported by those exposed to greater than six occurrences of CPA and those exposed to two or three types of Physical Assault.

Table 4.

Mean nicotine dependence and mean number of cigarettes smoked per day among current smokers as a function of trauma types

| Category of Trauma | Nicotine Dependence Mean (SE) | p-value | Cigarettes per day Mean (SE) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Type of trauma in last year |

||||

| Current Smoking in Past Year | ||||

| Unwanted Sexual Contact | n=201 | n=360 | ||

| None | 2.21 (.20) | referent | 7.25 (.62) | referent |

| 1 or more | 2.61 (.38) | ns | 8.03 (2.37) | ns |

| Physical Assault | n=237 | n=423 | ||

| None | 1.98 (.18) | referent | 6.71 (.56) | referent |

| 1 or more | 3.09 (44) | 0.03 | 7.58 (1.46) | ns |

| None | 1.98 (.18) | referent | 6.71 (.56) | referent |

| 1 of 3 Types | 2.85 (.34) | 0.03 | 7.63 (1.51) | ns |

| 2 - 3 Types | 3.67 (1.24) | ns | 7.44 (3.66) | ns |

| Interpersonal Violence | n=200 | n=359 | ||

| None | 2.27 (.25) | referent | 7.11 (.69) | referent |

| 1 or more | 2.28 (.24) | ns | 8.00 (1.21) | ns |

| None | 2.27 (.25) | referent | 7.11 (.69) | referent |

| 1 to 2 times | 1.63 (.27) | ns | 4.31 (.97) | 0.01 |

| 3 to 5 times | 2.18 (.69) | ns | 5.83 (1.21) | ns |

| greater than 6 times | 2.58 (.30) | ns | 10.72 (2.03) | ns |

|

Type of Trauma before 6th grade |

||||

| Current Regular Smoking | ||||

| CSA b/f 6th grade | n=3089 | n=3962 | ||

| None | 3.24 (.06) | referent | 11.67 (.25) | referent |

| Yes | 3.97 (.22) | 0.002 | 13.96 (1.15) | 0.05 |

| None | 3.24 (.06) | referent | 11.67 (.25) | referent |

| 1 to 2 times | 4.25 (.28) | 0.0007 | 15.00 (1.15) | 0.04 |

| 3 to 5 times | 3.34 (.49) | ns | 10.38 (1.55) | ns |

| Greater than 6 times | 3.36 (.44) | ns | 12.58 (1.54) | ns |

| CPA b/f 6th grade | ||||

| None | 3.16 (.08) | referent | 11.50 (.29) | referent |

| Yes | 3.53 (.10) | 0.004 | 12.57 (.37) | 0.01 |

| None | 3.16 (.08) | referent | 11.50 (.29) | referent |

| 1 to 2 times | 3.48 (.17) | ns | 12.75 (.56) | 0.03 |

| 3 to 5 times | 3.38 (.23) | ns | 12.15 (.69) | ns |

| greater than 6 times | 3.67 (.15) | 0.003 | 12.64 (.57) | 0.06 |

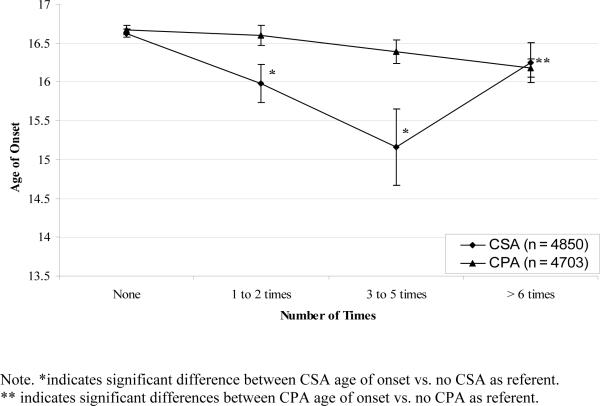

The relationship of CSA and CPA to mean age of smoking onset and significance levels can be seen in Figure 1. A significant decrease in age of regular smoking onset was seen among those exposed to the CSA. For CSA, smoking onset began nearly a full year earlier among those exposed to 3 to 5 events of CSA (M = 16.63, SE = .05 vs. M = 15.16. SE=.49).

Figure 1.

Onset of Regular Smoking by Number of Acts of Childhood Physical Abuse and Childhood Sexual Abuse.

DISCUSSION

Utilizing a nationally representative sample of young adults, we found that exposure to traumatic events was associated with increased smoking. In particular, reports of trauma exposure during the past year of early adulthood were associated with up to a two fold increased risk of regular smoking in the past year. There was not a clear linear dose effect for many of the trauma variables, perhaps suggesting that only specific types of trauma at specific exposure levels confer risk for smoking behavior and nicotine dependence. Overall, these findings are in accord with a longitudinal study of adults conducted by Breslau et al. [5], and with other cross-sectional surveys of adolescents [7] and adults [8]. This study builds upon previous findings by examining how traumatic life experiences during the past year relate to young adult smoking and to how childhood trauma relate to smoking among a nationally representative sample.

Our findings also indicated that reports of childhood trauma were associated with an increased risk of smoking and greater nicotine dependence. In independent models, reports of CSA were associated with a greater risk of smoking and earlier age of onset than reports of CPA. However, in models that included both of these variables, a history of CPA appears to be a reliable predictor of ever-regular smoking independent of a history of CSA. In general, these findings in this sample of young adults confirm findings from others studies of older health care beneficiaries [29] and regional community samples [28].

Finally, we also found exposure to trauma in the last year was associated with smoking risk within that time frame. Most notably, exposure to physical assault yielded a two-fold increase in the odds of being an ever-regular smoker in the past year. Even after accounting for a reported history of relationship violence, exposure to physical assault remained a significant predictor of ever-regular smoking. This is consistent with findings from another study based on a nationally representative survey of adolescents [7], which found a two to three fold increase in the odds of current smoking among those who witnessed violence or were attacked with a weapon.

The multivariate models in this investigation controlled for factors that have been associated with smoking, such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, highest level of parental education, depressive symptoms, and parental smoking. Across all multivariate models, approximately a 2-5 % increased odds of smoking for a one unit increase in current reports of depressive symptoms on the CES-D was observed. The directionality between smoking and depression is not completely understood [30]. However, the odds reported in the current study represent the odds associated with trauma exposure accounting for current depression level. We did not find that current levels of depressive symptoms interacted with any of the reported trauma types. Thus, it does not appear that current depressive symptoms among this non-clinical sample increased the association between trauma and smoking. Other studies have employed a similar strategy of controlling for psychiatric diagnosis of depression or PTSD along with trauma exposure, but have not examined interaction effects [7]. At least one other study examined depressed affect, smoking during middle adulthood, and exposure to adverse childhood experiences, showing that depression was higher among smokers with a greater number of adverse experiences reported. Unfortunately, these results were not tested using multivariate methods [29]. Further studies that examine trauma exposure, other psychiatric symptoms, and smoking may better elucidate these complex interactions [31].

A potential mechanism to explain these associations may be that among individuals who have a history of exposure to traumatic events and/or the diagnosis of PTSD, nicotine may be used in order to regulate stress and affective responses [32]. Commonly referred to as the self-medication model [33], it assumes that substances (i.e., nicotine) are used in order to regulate mood, affective states, or trauma related symptoms [32]. A growing body of laboratory and clinical research has demonstrated that mood states and trauma-related symptoms lead to increased urges and cravings [34, 35]. Smoking topography data has also shown that, compared to controls, trauma-exposed individuals who develop the full diagnosis of PTSD smoke more intensely in response to induced negative affect [36]. Thus, the significant associations observed here may be mediated by self-medication of negative mood states associated with the traumatic experience.

Limitations

One limitation of the current study is that clinical psychiatric diagnoses were not ascertained. Thus, we cannot determine how clinical levels of PTSD may relate to smoking in this population. The current investigation was also limited by the trauma exposure assessment. The original study was not designed to comprehensively measure trauma exposure, and although items used in this study inquired about exposure to a given experience, subjective emotional reaction to the events as required for a Criterion A event for PTSD in the DSM-IV [37] was not assessed. Nonetheless, the event types included are those shown to confer the greatest risk of PTSD and have a high probability of eliciting fear, horror, or helplessness [14, 38]. Replication utilizing a standardized measure of trauma exposure, including information about the emotional reaction and diagnostic status, would clarify and extend the current findings. Another limitation is that the data relies upon self report of smoking rather than biological measurements. Finally, our study was focused on salient predictors of smoking and trauma. Nonetheless, other variables such as exposure to high crime neighborhood environmental factors could contribute to both higher smoking rates and greater exposure to traumas. Future studies addressing the larger contextual factors are needed.

Despite limitations, the study has important strengths. Since adolescence is the developmental period during which smoking onset is most prevalent [39] and is also the period at which trauma exposure has the greatest probability of occurrence [14, 40], evaluation of the association during this time period is particularly relevant in contributing to our understanding of trauma exposure and smoking. Utilizing a nationally representative sample of U.S. young adults and controlling for important covariates, the consistently significant relationship between multiple trauma types and multiple smoking parameters provide the strongest support to date for this relationship. While it is encouraging that the rates of smoking have declined in the past 20 years, a high risk of smoking remains among certain subpopulations. Current study results demonstrate that trauma exposed young adults are one such subpopulation. It will be beneficial in future studies to focus on additional contributors to the association between trauma exposure and cigarette smoking (e.g., possible dose-response relationship for the number of traumatic events, genetic variables, psychiatric co-morbidity) in young adults, with the goal of reducing smoking in this vulnerable population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse K23DA017261-01 (FJM), K24DA016388 (MER and JCB), R21 DA019704-01 (JCB), National Cancer Institute 2R01 CA081595 (JCB), and Veterans Affairs Merit Award MH-0018 (JCB).

This research uses data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health: J. Richard Udry, PhD, principal investigator, and Peter Bearman, PhD) and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies, to the Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Persons interested in obtaining data files regarding for the Add Health project should contact Add Health Project, Carolina Population Center, 123 W Franklin St, Chapel Hill, NC 27516-2524 (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Miguel E. Roberts, Duke University Medical Center/Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Bernard F. Fuemmeler, Duke University Medical Center*

F. Joseph McClernon, Duke University Medical Center

Jean C. Beckham, Duke University Medical Center/Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center/VISN 6 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services Health, United States. 2005 doi: 10.3109/15360288.2015.1037530. [cited July 11, 2007]; Available from: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus05.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, et al. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000 Nov 22-29;284(20):2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalman D, Morissette SB, George TP. Co-morbidity of smoking in patients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2005 Mar-Apr;14(2):106–123. doi: 10.1080/10550490590924728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hourani LL, Yuan H, Bray RM, et al. Psychosocial correlates of nicotine dependence among men and women in the U.S. naval services. Addict Behav. 1999 Jul-Aug;24(4):521–536. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslau N, Davis GC, Schultz LR. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the incidence of nicotine, alcohol, and other drug disorders in persons who have experienced trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003 Mar;60(3):289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckham JC, Roodman AA, Shipley RH, et al. Smoking in Vietnam combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 1995 Jul;8(3):461–472. doi: 10.1007/BF02102970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick H, et al. Assault, PTSD, family substance use, and depression as risk factors for cigarette use in youth: findings from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Trauma Stress. 2000 Jul;13(3):381–396. doi: 10.1023/A:1007772905696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hapke U, Schumann A, Rumpf HJ, et al. Association of smoking and nicotine dependence with trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a general population sample. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005 Dec;193(12):843–846. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000188964.83476.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al Mamun A, Alati R, O'Callaghan M, et al. Does childhood sexual abuse have an effect on young adults' nicotine disorder (dependence or withdrawal)? Evidence from a birth cohort study. Addiction. 2007 Apr;102(4):647–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C.: 2000. `4th'. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jun 16;352(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Donnell ML, Creamer M, Pattison P. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma: understanding comorbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Aug;161(8):1390–1396. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: II. Psychiatric outcomes of childhood sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996 Oct;35(10):1365–1374. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, et al. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998 Jul;55(7):626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorndike FP, Wernicke R, Pearlman MY, et al. Nicotine dependence, PTSD symptoms, and depression proneness among male and female smokers. Addict Behav. 2006 Feb;31(2):223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris KM, Florey F, Tabor J, et al. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: research design. 2006 [cited Accessed October31]; Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- 17.Morasco BJ, Dornelas EA, Fischer EH, et al. Spontaneous smoking cessation during pregnancy among ethnic minority women: a preliminary investigation. Addict Behav. 2006 Feb;31(2):203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lerman C, Audrain J, Tercyak K, et al. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) symptoms and smoking patterns among participants in a smoking-cessation program. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001 Nov;3(4):353–359. doi: 10.1080/14622200110072156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kollins SH, McClernon FJ, Fuemmeler BF. Association between smoking and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in a population-based sample of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Oct;62(10):1142–1147. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991 Sep;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pomerleau CS, Carton SM, Lutzke ML, et al. Reliability of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire and the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence. Addict Behav. 1994 Jan-Feb;19(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, et al. The revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crockett LJ, Randall BA, Shen YL, et al. Measurement equivalence of the center for epidemiological studies depression scale for Latino and Anglo adolescents: a national study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005 Feb;73(1):47–58. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilman SE, Abrams DB, Buka SL. Socioeconomic status over the life course and stages of cigarette use: initiation, regular use, and cessation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003 Oct;57(10):802–808. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Derzon JH, Lipsey MW. Predicting tobacco use to age 18: a synthesis of longitudinal research. Addiction. 1999 Jul;94(7):995–1006. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9479955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institute RT . In: SUDAAN User's Manual. Institute RT, editor. Research Triangle Park, NC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Health and Human Services . SAMHSA. Office of Applied Studies; 2003. Results from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nichols HB, Harlow BL. Childhood abuse and risk of smoking onset. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004 May;58(5):402–406. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.008870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA. 1999 Nov 3;282(17):1652–1658. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998 Nov;18(7):765–794. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morissette SB, Tull MT, Gulliver SB, et al. Anxiety, anxiety disorders, tobacco use, and nicotine: a critical review of interrelationships. Psychol Bull. 2007 Mar;133(2):245–272. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Paronis CA. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychol Bull. 2003 Mar;129(2):270–304. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keane TM, Gerardi RJ, Lyons JA, et al. The interrelationship of substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Epidemiological and clinical considerations. Recent Dev Alcohol. 1988;6:27–48. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-7718-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coffey SF, Lombardo TW. Effects of smokeless tobacco-related sensory and behavioral cues on urge, affect, and stress. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998 Nov;6(4):406–418. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.4.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beckham JC, Lytle BL, Vrana SR, et al. Smoking withdrawal symptoms in response to a trauma-related stressor among Vietnam combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Addict Behav. 1996 Jan-Feb;21(1):93–101. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McClernon FJ, Beckham JC, Mozley SL, et al. The effects of trauma recall on smoking topography in posttraumatic stress disorder and non-posttraumatic stress disorder trauma survivors. Addict Behav. 2005;30(2):247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. `4th ed.'. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Breslau N, Kessler RC. The stressor criterion in DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder: an empirical investigation. Biol Psychiatry. 2001 Nov 1;50(9):699–704. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Center for Disease Control and Prevention . Department of Health and Human Services PHS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. Department of Health and Human Services; 1994. Preventing tobacco use among young people: A report of the Surgeon General. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cloitre M. Trauma and PTSD. CNS Spectrums. 2004;9(9):4–5. [Google Scholar]