Abstract

Oxidative modifications are a hallmark of oxidative imbalance in the brains of individuals with Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and prion diseases and their respective animal models. While the causes of oxidative stress are relatively well-documented, the effects of chronically reducing oxidative stress on cognition, pathology and biochemistry require further clarification. To address this, young and aged control and amyloid-β protein precursor-over-expressing mice were fed a diet with added R-alpha lipoic acid for 10 months to determine the effect of chronic antioxidant administration on the cognition and neuropathology and biochemistry of the brain. Both wild type and transgenic mice treated with R-alpha lipoic acid displayed significant reductions in markers of oxidative modifications. On the other hand, R-alpha lipoic acid had little effect on Y-maze performance throughout the study and did not decrease end-point amyloid-β load. These results suggest that, despite the clear role of oxidative stress in mediating amyloid pathology and cognitive decline in ageing and AβPP-transgenic mice, long-term antioxidant therapy, at levels within tolerable nutritional guidelines and which reduce oxidative modifications, have limited benefit.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid-β, antioxidant, R-alpha lipoic acid, transgenic mice

Introduction

Oxidative modifications have been proposed as one biochemical change that could lead to the neuropathology and neuronal dysfunction and death found in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1–3]. Early work focused on late stage oxidative damage, such as advanced glycation end-products [4] and carboxymethyllysine [5] as the first oxidative modifications found in neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) and plaques containing tau and amyloid-β fibrils (Aβ), respectively. Later studies showed tau phosphorylation, notably the Alz-50 epitope often regarded as an ‘early’ marker of NFT development [6], occurring coincident with markers of oxidative stress [7,8] and led to the notion that oxidative modification, particularly lipid peroxidation products, such as 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) and related compounds [8], were involved in the fibrillization and aggregation of tau [9,10]. Consistent with this, HNE-protein adducts are present at higher levels within pyramidal neurons of AD as compared to controls [11]. Of note, damage to neuronal nucleic acids, in particular RNA, is significantly increased in AD, with the highest levels seen before the development of large numbers of NFT and amyloid plaques, suggesting oxidative damage as one of the earliest events in disease pathogenesis [12–15].

Of clear importance is the fact that oxidative imbalance is found at all stages of AD [16,17]. Diseased neurons can remain viable for 10 years or longer [18,19] and as such must have sufficient protective mechanisms to maintain normal homeostasis. However, as a neurodegenerative disorder, at some point in the disease, the oxidative insults may overwhelm cellular antioxidant defense systems leading to cellular dysfunction and death. Unfortunately, antioxidant therapy studies to date have focused on either administering antioxidants to patients well into the disease course or for shorter durations and have resulted in clinically equivocal or slight measurable benefit [20–22]. On the other hand, while a comprehensive review of many trials utilizing antioxidants for various disorders has shown that, as a group, there was no adverse effect, certain compounds under specific circumstances were correlated with higher mortality rates [23]. One reason may be that phenolic antioxidants, as well as others, produce pro-oxidant intermediates while scavenging free radicals, which can be counterproductive [24]. We hypothesize that the effects of antioxidant therapy work to help cellular function and survival, but only with selected antioxidants and at levels and timepoints in the disease course that will augment endogenous oxidative responses [25].

The antioxidant R-alpha lipoic acid (LA) has been suggested as a therapeutic that might act to increase the production of acetylcholine or as a chelator of redox-active metals or even to combat the accumulation of lipid peroxidation products [26,27]. In this respect, LA used in conjunction with acetyl carnitine protects neuronal cells in vitro from the effects of HNE-toxicity [28] and, at least in some cases, this was shown to be protective via cell signalling mechanisms including the extracellular signal-related kinase pathways, which are dysregulated in AD [29–31]. Importantly, the antioxidant capacity of lipoic acid and its readily reduced form dihydrolipoic acid have been shown to fully attenuate the deleterious phenotype of vitamin E deficiency in a mouse model [32].

In this study, we found that while the long-term administration of LA in control mice and mice over-expressing amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP) did significantly lower the levels of oxidative markers in both wild type and transgenic mice, there were neither effects on cognition as measured by the Y-maze nor on Aβ load. Overall, the findings support the efficacy of long-term antioxidant supplementation to combat the effects of oxidative modifications, but a functional role of these modifications on normal ageing and diseased states is not supported.

Materials and methods

Animals

Twenty mice (B6SJL) were available for this study, nine wild type and 11 transgenic for AβPP Tg2576 [33], aged 6.25–11.5 months at the onset of the study. Wild-type and transgenic mice were divided into groups receiving either normal or an LA supplemented diet (see Table I). All animals were housed individually in microisolator cages in the same room on a schedule of 12 h light and dark and offered environmental enrichment. Intake of food, water, weight, behaviour and enrichment were all carefully monitored for the 10-month period of study. Body weights were recorded every month and r-values obtained. No group (normal or LA-enriched food) showed any significant trend. One animal exhibited very low levels of activity and one animal exhibited continuous running in circles in his cage while all others appeared normal. Every other day the animals were observed by either laboratory personnel or animal centre technicians and veterinarians. All experiments were approved by the institutional animal use and care committee (Case Western Reserve University IACUC).

Table I.

Transgenic status, diet type, age at onset of experimental diet and age at the end of the study for the mice used.

| Mouse type | Diet | Age at onset (months) |

Age at end (months) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Normal | 6.25 | 16.25 |

| Wild-type | Normal | 6.25 | 16.25 |

| Wild-type | Normal | 7 | 17 |

| Wild-type | Normal | 11.5 | 21.5 |

| Wild-type | Lipoic acid | 7 | 17 |

| Wild-type | Lipoic acid | 7 | 17 |

| Wild-type | Lipoic acid | 8.5 | 16† |

| Wild-type | Lipoic acid | 11 | 21 |

| Wild-type | Lipoic acid | 11.5 | 21.5 |

| Tg2576 | Normal | 6.25 | 16.25 |

| Tg2576 | Normal | 6.25 | 16.25 |

| Tg2576 | Normal | 7 | 14.5† |

| Tg2576 | Normal | 8.5 | 18.5 |

| Tg2576 | Normal | 11.5 | 21.5 |

| Tg2576 | Normal | 12 | 22 |

| Tg2576 | Lipoic acid | 6.25 | 16.25* |

| Tg2576 | Lipoic acid | 6.25 | 16.25 |

| Tg2576 | Lipoic acid | 7 | 17 |

| Tg2576 | Lipoic acid | 11.5 | 21.5 |

| Tg2576 | Lipoic acid | 11.5 | 21.5 |

mouse not included in behaviour testing due to inactivity.

died before the end of the study.

Diet

Administration of the supplement through the food was chosen to mimic a routine therapy for human application and has been shown to cross the blood–brain barrier [34]. LA (98.97%) was supplied by NeoGen (Lansing, MI) and incorporated into pelleted AIN93M diet (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) at a concentration for an expected dietary intake of 30 mg/kg per day. The LD50 for rats was found to be ~ 500 mg/kg [35] and studies using between 25–100 mg/kg showed measurable reductions in oxidative stress in other models [26,36]. For this project, all food was administered by the laboratory personnel. Throughout the study, new food was routinely administered to all animals. The weight of fresh food and any food remaining, including any crumbs that could be collected, was recorded. Thus, the approximate amount of food eaten and thus the true daily dosage of LA was determined. At the same time, all animals were weighed to note any physical differences resulting from the two diets. Comparing the beginning and ending weights showed no significant weight changes between any of the groups or diets.

All animals ate very well and no statistically significant differences were seen between the animals on the normal diet vs the LA diet (p = 0.85 for the transgenic and p = 0.35 for the wild-type mice). It was determined that the animals actually ingested, on average, 4.2 ± 0.7 grams of food per day, slightly less than the proposed 5 g/day.

Toxicity test

Since this project was a long-term study, a toxicity test was designed to test any ill-effects of the LA supplemented diet. Using reported LD50 rates of 400–500 mg/kg body weight in rats, two additional mice were fed 5 × and 15 × the experimental dosage or 150 mg/kg and 450 mg/kg for 2 weeks. The mice ate the food normally and showed no behavioural or physical ill effects, up to an additional 6 weeks.

Behaviour testing

Y-maze analysis has been shown to be a reliable, noninvasive test to determine cognitive changes in the Tg2576 mouse [37–39]. The Y-maze apparatus consisted of three arms 32 cm (long) × 10 cm (wide) with 26-cm walls [40]. All animals were tested in a randomized order at the start and end of the experimental protocol. Testing was performed in the same room and at the same time (between 8–10 am) to ensure environmental consistency. Briefly, each animal was placed into the centre of the Y-maze and each arm entry was recorded. An entry into an arm was considered valid if all four paws entered the arm. An alternation was defined as three consecutive entries in three different arms (i.e. 1, 2, 3 or 2, 3, 1, etc). The percentage alternation score was calculated using the following formula: Total alternation number/Total number of entries − 2)*100. Furthermore, total number of arm entries was used as a measure of general activity in the animals. The maze was wiped clean with 70% ethanol between each animal to minimize odour cues.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test and ANOVA were used for statistical evaluation.

Immunohistochemistry

At the end of the study, all mice were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital and the brain removed. The brains were immediately dissected sagitally, with one hemisphere fixed in methacarn (methanol:chloroform: acetic acid; 6:3:1) and the other frozen in liquid nitrogen. After 16 h the fixed tissue was transferred to 70% ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Immunostaining of the 6 µm paraffin sections was performed using the peroxidase–anti-peroxidase method with DAB as the chromogen. Assessment was made either qualitatively or quantitatively by measuring the percentage area covered in the hippocampal and cortical region for Ab and for protein-bound HNE analysis by measuring the cellular densitometric levels using image analysis software (Axiovision Rel 4.5, Zeiss) [39,41].

Dot-blot analysis

Frozen brain samples were homogenized in Trisbuffered saline (TBS, 50 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, pH = 7.6) and protein concentrations were determined using the BCA method (Pierce). Dot blot analysis of homogenized protein samples for all mice was performed in two separate experiments and in triplicate each time. Five micrograms of each mouse brain homogenate was dotted onto Immobilon (Millipore) and dried. Following a blocking step in 10% non-fat milk, primary antibodies were incubated overnight followed by peroxidase labelled secondary antibodies and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (Hyperfilm, Amersham). Results were scanned and densitometric values were obtained using Axiovision 4.5 (Zeiss) and expressed as the mean of all trials using the Student’s t-test to compare groups.

Antibodies used for all studies included rabbit antisera directed against Aβ1–42 (Biosource), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) [7,42], HNE [11], carboxymethyllysine [5], nitrotyrosine [43], monoclonal antibodies specific for Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 (gift of Fukumoto, H., Takeda Chemical Industries), as well as 4G8 (Pierce-Endogen) and the assay for redox active iron [44,45].

Results

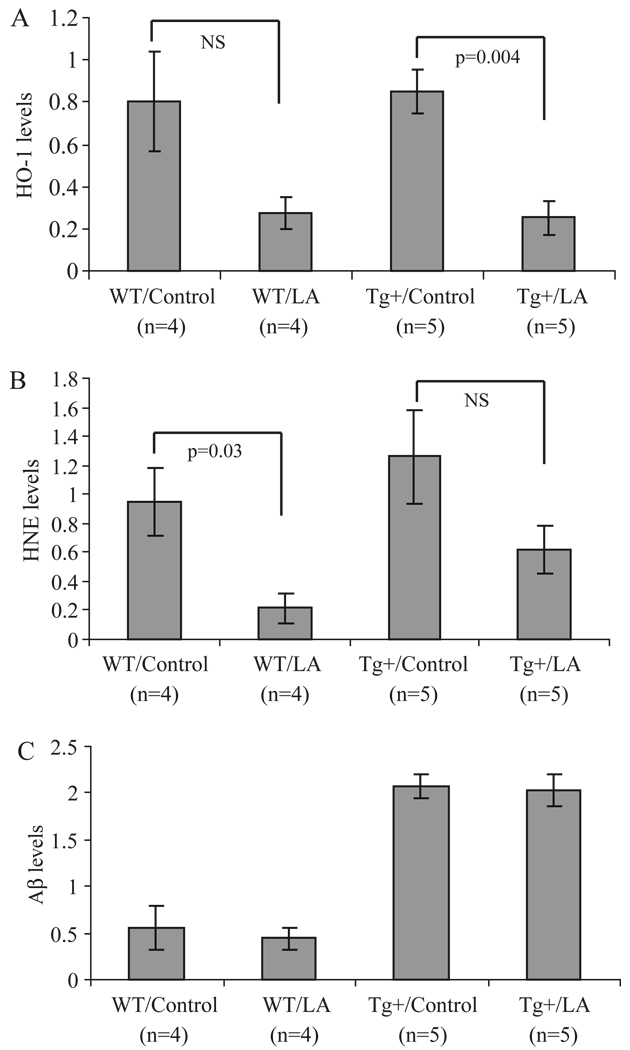

Markers of oxidative modification but not amyloid-β load are decreased with LA

A significant decrease in the expression of HO-1 (Figure 1A) as well as protein-bound HNE (Figure 1B) was observed in both wild-type and transgenic mice treated with LA using immunoblot analysis of brain homogenates. No differences were detected in either nitrotyrosine or carboxymethyllysine levels following LA treatment (data not shown) in control or transgenic mice. In AβPP transgenic mice, the Aβ load was not significantly changed in either control or transgenic mice by the LA diet (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Dot-blot analysis of total brain homogenate reveals striking differences in markers of oxidative damage. Specifically, in both wild-type and Tg2576 mice who received the LA-enriched diet, levels of HO-1 (A) and HNE (B) were reduced, in some cases significantly. Using this method, the amount of Aβ was also determined. In the Tg2576 mice, Aβ levels remained unchanged following the chronic LA diet (C).

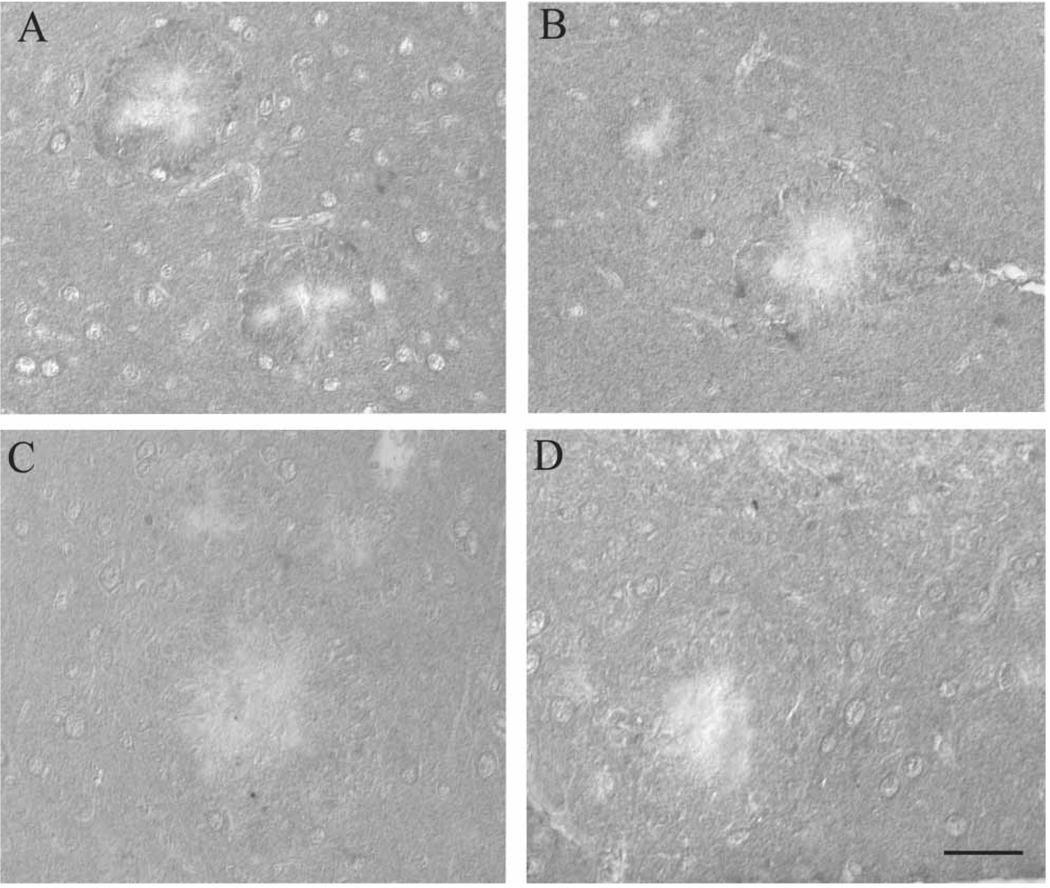

Immunocytochemistry

Supporting the immunoblot analyses, HO-1, which is expressed specifically in the regions surrounding the amyloid plaques in the Tg2576 mice on control diet (Figure 2A), was decreased around the amyloid plaques in mice receiving LA (Figure 2C). Similarly, the LA diet decreased protein-bound HNE expression surrounding Aβ plaques (Figure 2D) in mice compared to those on control diet (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis suggests accumulation of markers of oxidative damage in the brain is attenuated following chronic LA administration. HO-1, which accumulates around the Aβ depositions in the Tg2576 mice on normal diet (A), is reduced in the mice on the LA diet (C). Similarly, in the normal diet group, HNE accumulation surrounding the large Aβ plaques is evident (B), while essentially absent from all animals in the LA group (D). Scale bar = 50 µm.

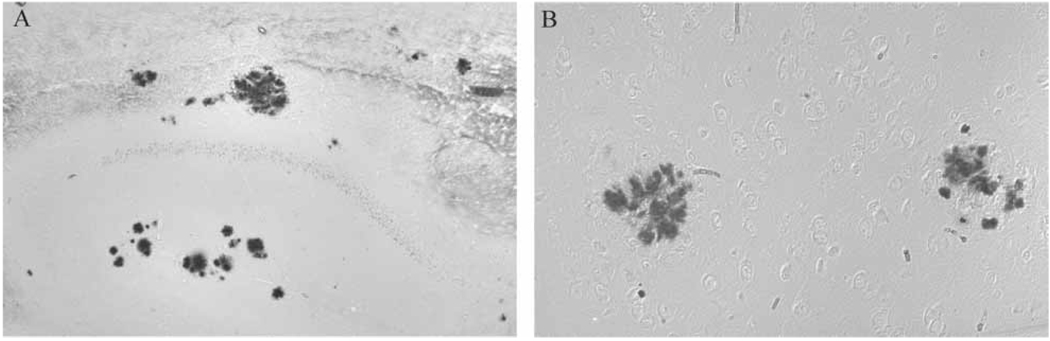

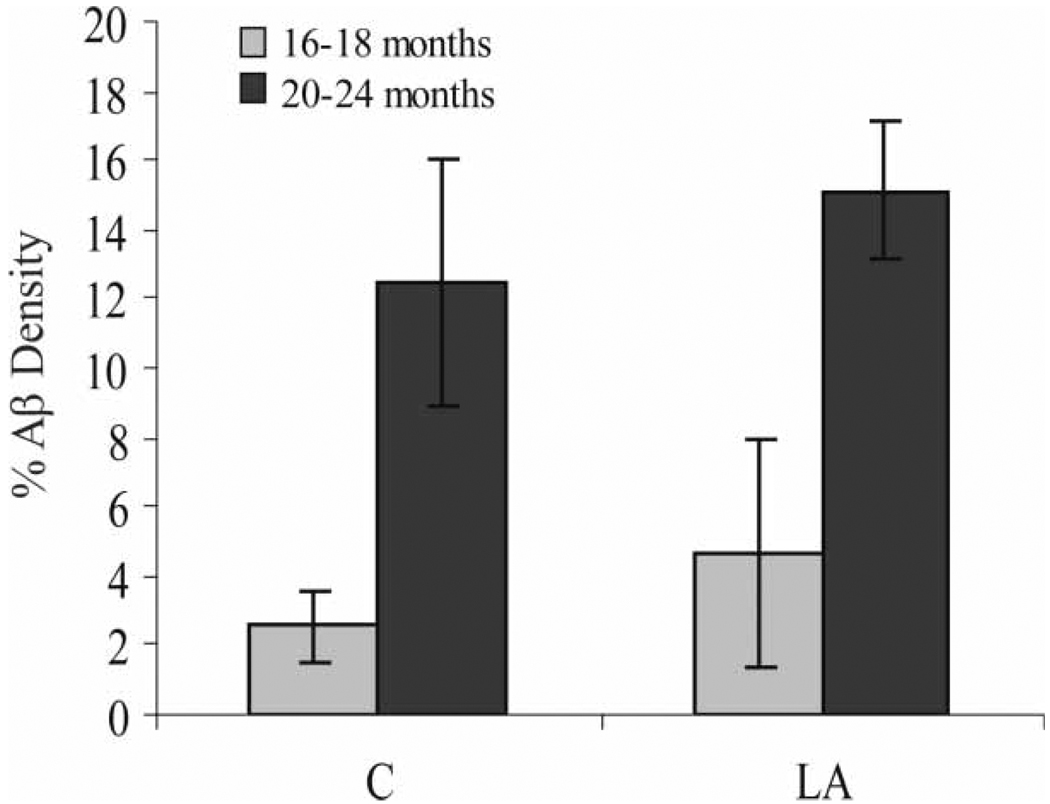

Redox active iron accumulation was specifically colocalized with Aβ plaques in all Tg2576 mice on the normal diet (Figure 3B) in the hippocampus and cortical regions as well as in all mice receiving the chronic LA diet (Figure 3A). Aβ load showed no change either qualitatively or after quantitative analysis of the area immunostained in the entire cortical and hippocampal area (Figure 4). Age at commencement of study did not impact amyloid load in LA-treated animals (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Redox-active iron, detected using a histochemical technique on paraffin embedded tissue sections, specifically accumulates with Aβ in Tg2576 mice on normal diet (B) and is present at the same levels even in mice on the LA diet in Aβ plaques in the hippocampus and cortex (A).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical analysis of Aβ density in the cortex and hippocampus, expressed as the percentage area covered by Aβ, as detected with antibody 4G8 in the Tg2576 mice. While the older mice have expectedly higher levels of Aβ deposition, those mice administered the LA-enriched diet for 10 months show no less Aβ deposition. Significantly, even in those mice beginning the diet at age 6–8 months, presumably before visible Aβ plaque development, by the end of the experiment after 10 months, Aβ deposition was also not attenuated.

Lipoic acid does not alter cognition

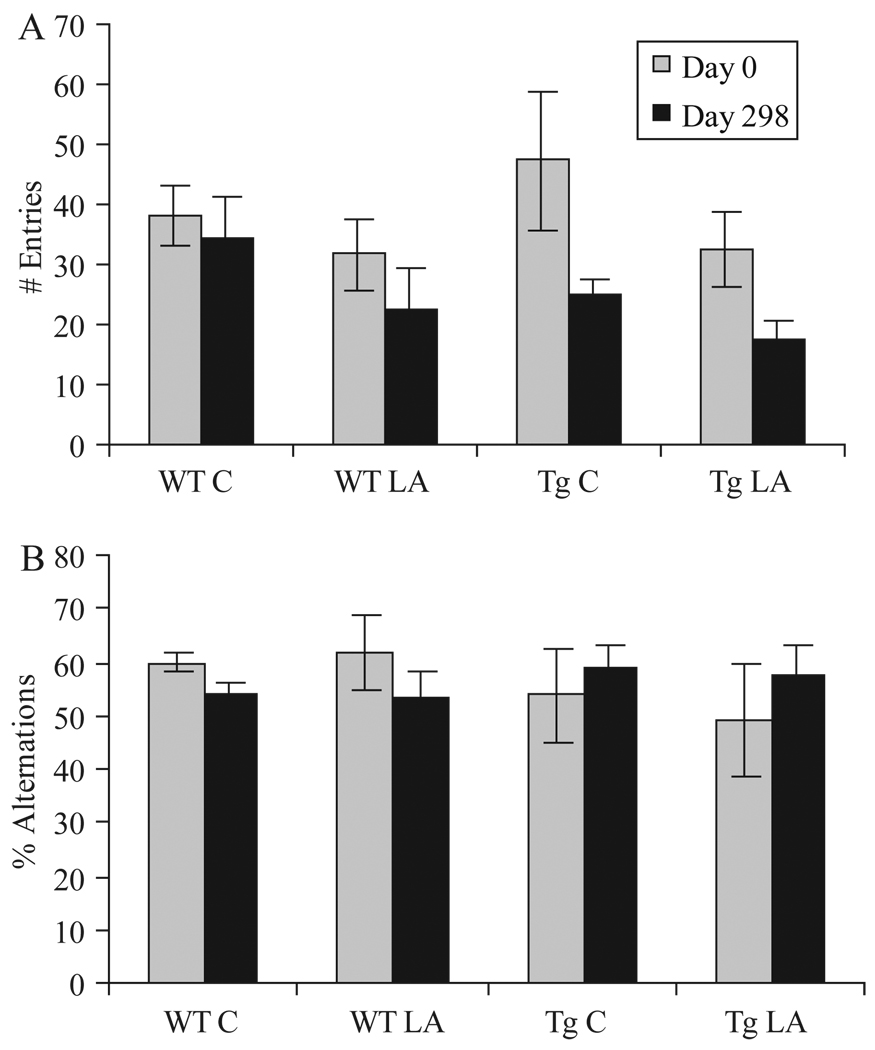

Behavioural testing using the Y-maze was carried out at day 0 to establish a baseline measurement and at the end of the study to determine the effects of LA diet in all groups. Tg2576 mice, as expected, showed fewer spontaneous alternations, a difference which was not statistically significant using ANOVA (p > 0.05). At day 298, neither the control nor LA diet group showed any significant difference in alternation behaviour from the beginning of the study (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Behaviour analysis, in this case administration of the Y-maze task, showed little change between the groups of mice on normal or LA-enriched diet. The number of arm entries, while higher in the Tg mice at the beginning of study in accordance with previous reports, decreased by the end of the study in all groups. No significant differences were noted between the mice on normal or LA-enriched diet (A). The percentage alternations, defined as entries into an arm different than the previous two choices, did not show any significant changes in any group (B).

Using ANOVA analysis, no significant differences (p > 0.05) were noted in either the number of entries or percentage alternations between the groups of mice aged 6–8 or 11–12 months of age at the beginning of the study (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study, we show that chronic administration of the antioxidant LA decreased the expression of protein and lipid peroxidation markers of oxidative modification within the brains of both control and AβPP-transgenic mice. In a related study [46], LA treatment improved Morris water maze performance in the Tg2576 mouse model, but was ineffective at modulating cognition in the Y-maze test or in the wild-type group for both tests. Significantly, the present work expands upon this by showing that administration of the antioxidant at timepoints well before the onset of plaque development and increasing the duration of treatment to 10 months neither improves cognition nor reduces amyloid deposition. Importantly, despite the small number of animals per group in our study, the Y-maze data for the control and Tg2576 mice at Day 0 is very similar to a previous study [37]. Nevertheless, we did not find differences in general activity across groups, as has been indicated previously for this task [38].

In addition to finding no change in Aβ protein levels or plaque load in the brains of Tg2576 following long-term administration of LA, no changes in nitrotyrosine or carboxymethyllysine levels following LA treatment were detected. However, substantial decreases in both HO-1 and protein-bound HNE levels following LA were evident in both the wild-type and Tg2576 mice. Studies measuring HO-1 in AβPP transgenic mice to date have looked at immunohisto-chemical localization of oxidative stress markers, where there is a striking accumulation of HO-1 around amyloid deposits [47]. Yet, HO-1 is readily detectable in wild-type mice by western blot analysis [48]. Further, strong induction of HO-1, detectable with western blot analysis, is usually highest at time points less than 24 h after stress (hyperthermia, ischemia, etc.) [49,50]. Therefore, the finding in the present study, that HO-1 dot blot analysis of total brain homogenate from aged animals undergoing chronic rather than acute stress shows insignificant differences, is not unexpected. Importantly, the focal accumulation of HO-1 around the amyloid deposits (Figure 2) is similar to what has been previously reported [47]. The significance of the results presented here is that both HO-1 levels and accumulation around amyloid deposits were dramatically lowered following LA dietary supplementation. Similarly, while the levels of HNE are higher in the AβPP transgenic mice when the total brain homogenate is assayed, future studies using larger groups should show significance. Again, however, the specific localization of HNE protein adducts accumulating around amyloid deposits is similar to previous reports and is also attenuated following antioxidant administration.

In the Tg2576 model, the significant development of Aβ deposits does not result in the extensive neuronal degeneration or loss as is found in AD [18,51]. The behavioural changes, which are well-documented in this model, are not associated with Aβ load [38]. The fact that Aβ deposition does not correlate well with AD severity [52] and occurs in many normal aged individuals [53,54], as well as in many other species [55,56], suggests Aβ is not a direct cause of the disease [18,57,58]. Many reports have even suggested that Aβ, as well as other fibrillar proteins in other neurodegenerative diseases, may accumulate as a protective response [59–64]. LA, however, while not decreasing Aβ deposition, has been shown to counteract the inflammation responses seen in mice following Aβ vaccination [65]. The present study, and others showing significant cognitive improvements following antioxidant therapies [66,67] yet no Aβ load attenuation, provides further evidence for the idea that amyloid is not a direct cause of the clinical manifestations of AD [68–70].

These studies may be applied to other non-Aβ expressing models of neurodegeneration, including the tauopathy models which display striking NFT accumulations. Increased reactive oxygen species, which are specifically localized in the NFT in AD, have also been found in the tauopathy mice [71]. In fact, some antioxidant therapies have been shown to delay the onset of the tau pathology which develops in these mice [72]. In another mouse model of neurodegeneration, using chronic systemic d-galactose exposure, treatment with LA effectively ameliorated neurodegeneration and cognitive function [73]. Further, in models of apolipoprotein E deficiency that result in intraneuronal amyloid inclusions, administration of combination antioxidant therapy both increased longevity and reduced inclusion formation in the hippocampus [74]. Antioxidants, therefore, attenuate oxidative damage in the Tg2576 mouse, in tauopathy models and in metabolic models and further work is needed to analyse the effects of LA on neurodegeneration involvement and cognitive decline in these and other models.

Restoring or maintaining the homeostatic balance between oxidative stressors and cellular responses is crucial to neuronal survival in both ageing and neurodegeneration [75]. Antioxidant therapy, either via nutritional guidelines [76] or pharmacological involvement, is often considered a low risk therapeutic strategy [77]. LA and other antioxidants have been used both in cell culture and animal models, most often showing significant and specific effects [78], though when applied to AD patients have only minor results including slowing the progression of the disease [22,79,80]. In a previous study with Tg2576 mice, administering vitamin E prior to but not after 5 months of age reduced Aβ deposition, yet the vitamin E attenuated lipid peroxidation in all groups [81]. These studies, taken together with the present work, suggest the action of LA may be targeting mitochondria, the most affected organelle responsible for AD development. Indeed, it has been shown that mitochondria are damaged in AD, structurally and functionally [82–84] and, therefore, antioxidants that easily penetrate not only the cell, but the mitochondria, may provide the greatest protection. To this end, compounds other than the naturally occurring antioxidants have much greater access to and provide protection to mitochondria from oxidative stressors [85,86].

The present study only augments both the safety and potential benefits of applying antioxidants long-term for healthy human ageing. Further studies using LA in conjunction with other antioxidants or at different concentrations is warranted. The one remarkable result from this long-term study is that chronic, low-dose antioxidant therapy, specifically LA in this case, is both safe and effective for lowering accumulations of oxidative stress products in both wild-type and transgenic aged mice. However, the lack of effect on cognitive decline or amyloid load by this therapy is not insignificant and provides evidence that antioxidants may be beneficial for healthy, normal ageing but should be used as a safe addition to other therapies aimed at stopping the neurodegeneration of AD.

Acknowledgements

Work in the authors’ laboratories is supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer’s Association and Philip Morris USA Inc. and Philip Morris International.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- AβPP

amyloid-β protein precursor

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- NFT

neurofibrillary tangles

- LA

R-alpha lipoic acid

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: Dr. Smith is, or has in the past been, a paid consultant for, owns equity or stock options in and/or receives grant funding from Neurotez, Neuropharm, Edenland, Panacea Pharmaceuticals, and Voyager Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Perry is a paid consultant for and/or owns equity or stock options in Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Voyager Pharmaceuticals, Panacea Pharmaceuticals and Neurotez Pharmaceuticals. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Markesbery WR. Oxidative stress hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23:134–147. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polidori MC, Griffiths HR, Mariani E, Mecocci P. Hallmarks of protein oxidative damage in neurodegenerative diseases: focus on Alzheimer’s disease. Amino Acids. 2007;32:553–559. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry G, Castellani RJ, Hirai K, Smith MA. Reactive oxygen species mediate cellular damage in Alzheimer disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 1998;1:45–55. doi: 10.3233/jad-1998-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith MA, Taneda S, Richey PL, Miyata S, Yan SD, Stern D, Sayre LM, Monnier VM, Perry G. Advanced Maillard reaction end products are associated with Alzheimer disease pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5710–5714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castellani RJ, Harris PL, Sayre LM, Fujii J, Taniguchi N, Vitek MP, Founds H, Atwood CS, Perry G, Smith MA. Active glycation in neurofibrillary pathology of Alzheimer disease: N(epsilon)-(carboxymethyl) lysine and hexitol-lysine. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:175–180. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver CL, Espinoza M, Kress Y, Davies P. Conformational change as one of the earliest alterations of tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:719–727. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeda A, Smith MA, Avila J, Nunomura A, Siedlak SL, Zhu X, Perry G, Sayre LM. In Alzheimer’s disease, heme oxygenase is coincident with Alz50, an epitope of tau induced by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal modification. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1234–1241. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Q, Smith MA, Avila J, DeBernardis J, Kansal M, Takeda A, Zhu X, Nunomura A, Honda K, Moreira PI, Oliveira CR, Santos MS, Shimohama S, Aliev G, de la Torre J, Ghanbari HA, Siedlak SL, Harris PL, Sayre LM, Perry G. Alzheimerspecific epitopes of tau represent lipid peroxidation-induced conformations. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:746–754. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith MA, Siedlak SL, Richey PL, Nagaraj RH, Elhammer A, Perry G. Quantitative solubilization and analysis of insoluble paired helical filaments from Alzheimer disease. Brain Res. 1996;717:99–108. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01473-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez-Ramos A, Diaz-Nido J, Smith MA, Perry G, Avila J. Effect of the lipid peroxidation product acrolein on tau phosphorylation in neural cells. J Neurosci Res. 2003;71:863–870. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sayre LM, Zelasko DA, Harris PL, Perry G, Salomon RG, Smith MA. 4-Hydroxynonenal-derived advanced lipid peroxidation end products are increased in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 1997;68:2092–2097. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68052092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nunomura A, Perry G, Pappolla MA, Wade R, Hirai K, Chiba S, Smith MA. RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of vulnerable neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1959–1964. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01959.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nunomura A, Chiba S, Lippa CF, Cras P, Kalaria RN, Takeda A, Honda K, Smith MA, Perry G. Neuronal RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of familial Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Honda K, Smith MA, Zhu X, Baus D, Merrick WC, Tartakoff AM, Hattier T, Harris PL, Siedlak SL, Fujioka H, Liu Q, Moreira PI, Miller FP, Nunomura A, Shimohama S, Perry G. Ribosomal RNA in Alzheimer disease is oxidized by bound redox-active iron. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20978–20986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markesbery WR, Lovell MA. Damage to lipids, proteins, DNA, and RNA in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:954–956. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.7.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu X, Lee HG, Casadesus G, Avila J, Drew K, Perry G, Smith MA. Oxidative imbalance in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2005;31:205–217. doi: 10.1385/MN:31:1-3:205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perry G, Cash AD, Smith MA. Alzheimer disease and oxidative stress. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2002;2:120–123. doi: 10.1155/S1110724302203010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castellani RJ, Lee HG, Zhu X, Nunomura A, Perry G, Smith MA. Neuropathology of Alzheimer disease: pathognomonic but not pathogenic. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2006;111:503–509. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0071-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morsch R, Simon W, Coleman PD. Neurons may live for decades with neurofibrillary tangles. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:188–197. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199902000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thal LJ, Ferris SH, Kirby L, Block GA, Lines CR, Yuen E, Assaid C, Nessly ML, Norman BA, Baranak CC, Reines SA. A randomized, double-blind, study of rofecoxib in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1204–1215. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, Klauber MR, Schafer K, Grundman M, Woodbury P, Growdon J, Cotman CW, Pfeiffer E, Schneider LS, Thal LJ. A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol, or both as treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1216–1222. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704243361704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grundman M, Grundman M, Delaney P. Antioxidant strategies for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Nutr Soc. 2002;61:191–202. doi: 10.1079/PNS2002146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;297:842–857. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chyan YJ, Poeggeler B, Omar RA, Chain DG, Frangione B, Ghiso J, Pappolla MA. Potent neuroprotective properties against the Alzheimer beta-amyloid by an endogenous melatonin-related indole structure, indole-3-propionic acid. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21937–21942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nunomura A, Castellani RJ, Zhu X, Moreira PI, Perry G, Smith MA. Involvement of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:631–641. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000228136.58062.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmquist L, Stuchbury G, Berbaum K, Muscat S, Young S, Hager K, Engel J, Munch G. Lipoic acid as a novel treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreira PI, Harris PL, Zhu X, Santos MS, Oliveira CR, Smith MA, Perry G. Lipoic acid and N-acetyl cysteine decrease mitochondrial-related oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease patient fibroblasts. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;12:195–206. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-12210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdul HM, Butterfield DA. Involvement of PI3K/PKG/ERK1/2 signaling pathways in cortical neurons to trigger protection by cotreatment of acetyl-L-carnitine and alpha-lipoic acid against HNE-mediated oxidative stress and neurotoxicity: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:371–384. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu X, Raina AK, Lee HG, Chao M, Nunomura A, Tabaton M, Petersen RB, Perry G, Smith MA. Oxidative stress and neuronal adaptation in Alzheimer disease: the role of SAPK pathways. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5:571–576. doi: 10.1089/152308603770310220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perry G, Roder H, Nunomura A, Takeda A, Friedlich AL, Zhu X, Raina AK, Holbrook N, Siedlak SL, Harris PL, Smith MA. Activation of neuronal extracellular receptor kinase (ERK) in Alzheimer disease links oxidative stress to abnormal phosphorylation. Neuroreport. 1999;10:2411–2415. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199908020-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu X, Raina AK, Perry G, Smith MA. Alzheimer’s disease: the two-hit hypothesis. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:219–226. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00707-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Podda M, Tritschler HJ, Ulrich H, Packer L. Alpha-lipoic acid supplementation prevents symptoms of vitamin E deficiency. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204:98–104. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morini M, Roccatagliata L, Dell’Eva R, Pedemonte E, Furlan R, Minghelli S, Giunti D, Pfeffer U, Marchese M, Noonan D, Mancardi G, Albini A, Uccelli A. Alpha-lipoic acid is effective in prevention and treatment of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;148:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wollin SD, Jones PJ. Alpha-lipoic acid and cardiovascular disease. J Nutr. 2003;133:3327–3330. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farr SA, Poon HF, Dogrukol-Ak D, Drake J, Banks WA, Eyerman E, Butterfield DA, Morley JE. The antioxidants alpha-lipoic acid and N-acetylcysteine reverse memory impairment and brain oxidative stress in aged SAMP8 mice. J Neurochem. 2003;84:1173–1183. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.King DL, Arendash GW. Behavioral characterization of the Tg2576 transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease through 19 months. Physiol Behav. 2002;75:627–642. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00639-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holcomb LA, Gordon MN, Jantzen P, Hsiao K, Duff K, Morgan D. Behavioral changes in transgenic mice expressing both amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 mutations: lack of association with amyloid deposits. Behav Genet. 1999;29:177–185. doi: 10.1023/a:1021691918517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casadesus G, Webber KM, Atwood CS, Pappolla MA, Perry G, Bowen RL, Smith MA. Luteinizing hormone modulates cognition and amyloid-beta deposition in Alzheimer APP transgenic mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casadesus G, Milliken EL, Webber KM, Bowen RL, Lei Z, Rao CV, Perry G, Keri RA, Smith MA. Increases in luteinizing hormone are associated with declines in cognitive performance. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;269:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nunomura A, Perry G, Aliev G, Hirai K, Takeda A, Balraj EK, Jones PK, Ghanbari H, Wataya T, Shimohama S, Chiba S, Atwood CS, Petersen RB, Smith MA. Oxidative damage is the earliest event in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:759–767. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.8.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith MA, Kutty RK, Richey PL, Yan SD, Stern D, Chader GJ, Wiggert B, Petersen RB, Perry G. Heme oxygenase-1 is associated with the neurofibrillary pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:42–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith MA, Richey Harris PL, Sayre LM, Beckman JS, Perry G. Widespread peroxynitrite-mediated damage in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2653–2657. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02653.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith MA, Harris PL, Sayre LM, Perry G. Iron accumulation in Alzheimer disease is a source of redox-generated free radicals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9866–9868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sayre LM, Perry G, Harris PL, Liu Y, Schubert KA, Smith MA. In situ oxidative catalysis by neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in Alzheimer’s disease: a central role for bound transition metals. J Neurochem. 2000;74:270–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinn JF, Bussiere JR, Hammond RS, Montine TJ, Henson E, Jones RE, Stackman RW., Jr Chronic dietary alpha-lipoic acid reduces deficits in hippocampal memory of aged Tg2576 mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:213–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith MA, Hirai K, Hsiao K, Pappolla MA, Harris PL, Siedlak SL, Tabaton M, Perry G. Amyloid-beta deposition in Alzheimer transgenic mice is associated with oxidative stress. J Neurochem. 1998;70:2212–2215. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70052212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matz PG, Copin JC, Chan PH. Cell death after exposure to subarachnoid hemolysate correlates inversely with expression of CuZn-superoxide dismutase. Stroke. 2000;31:2450–2459. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ryter SW, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase-1: molecular mechanisms of gene expression in oxygen-related stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4:625–632. doi: 10.1089/15230860260220120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maeda S, Nakatsuka I, Hayashi Y, Higuchi H, Shimada M, Miyawaki T. Heme oxygenase-1 induction in the brain during lipopolysaccharide-induced acute inflammation. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:663–667. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Irizarry MC, Soriano F, McNamara M, Page KJ, Schenk D, Games D, Hyman BT. Abeta deposition is associated with neuropil changes, but not with overt neuronal loss in the human amyloid precursor protein V717F (PDAPP) transgenic mouse. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7053–7059. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-07053.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berg L, McKeel DW, Jr, Miller JP, Baty J, Morris JC. Neuropathological indexes of Alzheimer’s disease in demented and nondemented persons aged 80 years and older. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:349–358. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540040011008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bell MA, Ball MJ. Neuritic plaques and vessels of visual cortex in aging and Alzheimer’s dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 1990;11:359–370. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(90)90001-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rafalowska J, Barcikowska M, Wen GY, Wisniewski HM. Laminar distribution of neuritic plaques in normal aging, Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome. Acta Neuropathol. 1988;77:21–25. doi: 10.1007/BF00688238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sloane JA, Pietropaolo MF, Rosene DL, Moss MB, Peters A, Kemper T, Abraham CR. Lack of correlation between plaque burden and cognition in the aged monkey. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;94:471–478. doi: 10.1007/s004010050735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Borras D, Ferrer I, Pumarola M. Age-related changes in the brain of the dog. Vet Pathol. 1999;36:202–211. doi: 10.1354/vp.36-3-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rottkamp CA, Atwood CS, Joseph JA, Nunomura A, Perry G, Smith MA. The state versus amyloid-beta: the trial of the most wanted criminal in Alzheimer disease. Peptides. 2002;23:1333–1341. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee HG, Casadesus G, Zhu X, Takeda A, Perry G, Smith MA. Challenging the amyloid cascade hypothesis: senile plaques and amyloid-beta as protective adaptations to Alzheimer disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1019:1–4. doi: 10.1196/annals.1297.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Castellani RJ, Lee HG, Perry G, Smith MA. Antioxidant protection and neurodegenerative disease: the role of amyloid-beta and tau. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2006;21:126–130. doi: 10.1177/153331750602100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee HG, Petersen RB, Zhu X, Honda K, Aliev G, Smith MA, Perry G. Will preventing protein aggregates live up to its promise as prophylaxis against neurodegenerative diseases? Brain Pathol. 2003;13:630–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith MA, Casadesus G, Joseph JA, Perry G. Amyloid-beta and tau serve antioxidant functions in the aging and Alzheimer brain. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1194–1199. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hayashi T, Shishido N, Nakayama K, Nunomura A, Smith MA, Perry G, Nakamura M. Lipid peroxidation and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal formation by copper ion bound to amyloid-beta peptide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:1552–1559. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakamura M, Shishido N, Nunomura A, Smith MA, Perry G, Hayashi Y, Nakayama K, Hayashi T. Three histidine residues of amyloid-beta peptide control the redox activity of copper and iron. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2007;46:12737–12743. doi: 10.1021/bi701079z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chan C-W, Dharmarajan A, Atwood CS, Huang X, Tanzi RE, Bush AI, Martins RN. Anti-apoptotic action of Alzheimer Abeta. Alzheimers Rep. 1999;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jesudason EP, Masilamoni JG, Kirubagaran R, Davis GD, Jayakumar R. The protective role of DL-alpha-lipoic acid in biogenic amines catabolism triggered by Abeta amyloid vaccination in mice. Brain Res Bull. 2005;65:361–367. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Malm TM, Iivonen H, Goldsteins G, Keksa-Goldsteine V, Ahtoniemi T, Kanninen K, Salminen A, Auriola S, Van Groen T, Tanila H, Koistinaho J. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate activates Akt and improves spatial learning in APP/PS1 mice without affecting beta-amyloid burden. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3712–3721. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0059-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Joseph JA, Denisova NA, Arendash G, Gordon M, Diamond D, Shukitt-Hale B, Morgan D. Blueberry supplementation enhances signaling and prevents behavioral deficits in an Alzheimer disease model. Nutr Neurosci. 2003;6:153–162. doi: 10.1080/1028415031000111282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Joseph J, Shukitt-Hale B, Denisova NA, Martin A, Perry G, Smith MA. Copernicus revisited: amyloid beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:131–146. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perry G, Nunomura A, Raina AK, Smith MA. Amyloid-beta junkies. Lancet. 2000;355:757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)72173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith MA, Atwood CS, Joseph JA, Perry G. Predicting the failure of amyloid-beta vaccine. Lancet. 2002;359:1864–1865. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08695-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.David DC, Hauptmann S, Scherping I, Schuessel K, Keil U, Rizzu P, Ravid R, Drose S, Brandt U, Muller WE, Eckert A, Gotz J. Proteomic and functional analyses reveal a mitochondrial dysfunction in P301L tau transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23802–23814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500356200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nakashima H, Ishihara T, Yokota O, Terada S, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Kuroda S. Effects of alpha-tocopherol on an animal model of tauopathies. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cui X, Zuo P, Zhang Q, Li X, Hu Y, Long J, Packer L, Liu J. Chronic systemic D-galactose exposure induces memory loss, neurodegeneration, and oxidative damage in mice: protective effects of R-alpha-lipoic acid. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:647–654. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Veurink G, Liu D, Taddei K, Perry G, Smith MA, Robertson TA, Hone E, Groth DM, Atwood CS, Martins RN. Reduction of inclusion body pathology in ApoE-deficient mice fed a combination of antioxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:1070–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moreira PI, Zhu X, Lee HG, Honda K, Smith MA, Perry G. The (un)balance between metabolic and oxidative abnormalities and cellular compensatory responses in Alzheimer disease. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:501–506. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith MA, Petot GJ, Perry G. Diet and oxidative stress: a novel synthesis of epidemiological data on Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 1999;1:203–206. doi: 10.3233/jad-1999-14-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ancelin ML, Christen Y, Ritchie K. Is antioxidant therapy a viable alternative for mild cognitive impairment? Examination of the evidence. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24:1–19. doi: 10.1159/000102567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gasic-Milenkovic J, Loske C, Munch G. Advanced glycation endproducts cause lipid peroxidation in the human neuronal cell line SH-SY5Y. J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5:25–30. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hager K, Kenklies M, McAfoose J, Engel J, Mucnh G. Alpha-lipoic acid as a new treatment option for Alzheimer’s disease—a 48 months follow-up analysis. In: Gerlach M, Deckert J, Double K, Kouytsillieri E, editors. J Neural Transm Suppl 72. Springer; 2007. pp. 189–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pitchumoni SS, Doraiswamy PM. Current status of antioxidant therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1566–1572. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sung S, Yao Y, Uryu K, Yang H, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Pratico D. Early vitamin E supplementation in young but not aged mice reduces Abeta levels and amyloid deposition in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2004;18:323–325. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0961fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hirai K, Aliev G, Nunomura A, Fujioka H, Russell RL, Atwood CS, Johnson AB, Kress Y, Vinters HV, Tabaton M, Shimohama S, Cash AD, Siedlak SL, Harris PL, Jones PK, Petersen RB, Perry G, Smith MA. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3017–3023. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03017.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang X, Su B, Perry G, Smith MA, Zhu X. Insights into amyloid-beta-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:1569–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang X, Su B, Fujioka H, Zhu X. Dynamin-like protein 1 reduction underlies mitochondrial morphology and distribution abnormalities in fibroblasts from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease patients. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:470–482. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.071208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Reddy PH, Beal MF. Amyloid beta, mitochondrial dysfunction and synaptic damage: implications for cognitive decline in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Reddy PH. Mitochondrial medicine for aging and neurode-generative diseases. Neuromolecular Med. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s12017-008-8044-z. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]