Abstract

Objective

Use of video recordings of newborn infants to determine: (1) if clinicians agreed whether infants were pink; and (2) the pulse oximeter oxygen saturation (Spo2) at which infants first looked pink.

Methods

Selected clips from video recordings of infants taken immediately after delivery were shown to medical and nursing staff. The infants received varying degrees of resuscitation (including none) and were monitored with pulse oximetry. The oximeter readings were obscured to observers but known to the investigators. A timer was visible and the sound was inaudible. The observers were asked to indicate whether each infant was pink at the beginning, became pink during the clip, or was never pink. If adjudged to turn pink during the clip, observers recorded the time this occurred and the corresponding Spo2 was determined.

Results

27 clinicians assessed videos of 20 infants (mean (SD) gestation 31(4) weeks). One infant (5%) was perceived to be pink by all observers. The number of clinicians who thought each of the remaining 19 infants were never pink varied from 1 (4%) to 22 (81%). Observers determined the 10 infants with a maximum Spo2 ⩾95% never pink on 17% (46/270) of occasions. The Spo2 at which individual infants were perceived to turn pink varied from 10% to 100%.

Conclusion

Among clinicians observing the same videos there was disagreement about whether newborn infants looked pink with wide variation in the Spo2 when they were considered to become pink.

Keywords: infant, newborn, resuscitation, colour, pulse oximetry

International guidelines on neonatal resuscitation recommend that the newborn infant's need for and response to resuscitation be assessed clinically.1 Determination of whether the newborn is pink or blue is an integral part of this assessment. Guidelines recommend examining the infant's face, trunk and mucous membranes to determine central cyanosis.1 There is variability in the determination of cyanosis between observers and poor correlation between this and the oxygen saturation of arterial blood samples (Sao2) in infants in the first 14 days of life.2 Accuracy of the clinical assessment of colour, in the minutes after delivery, is not known, nor the pulse oximetry oxygen saturation (Spo2) when they start to look pink. We used video recordings of newborn infants on a resuscitation trolley in the delivery room to determine:

if clinicians agreed whether infants were pink;

the Spo2, measured from the right hand, when infants were first perceived to be pink.

Methods

Setting

We made video recordings of infants in the delivery room at the Royal Women's Hospital, Melbourne starting in January 2004, and with endorsement from the research and ethics committees. A high definition digital video camera (Panasonic NV‐GS70 3CCD Matsushita Group, Osaka, Japan) was mounted on a Manfrotto Magic Arm with Super Clamp (Manfrotto, Italy) and positioned above the resuscitation cot to acquire a high‐quality view of the infant and any resuscitative interventions. This camera had a 3CCD (charged couple device) system, in which incident light is split in its three primary colours and each colour signal is collected separately. It is the system used in professional broadcast cameras, which the manufacturer reports “reproduces colours with exceptional fidelity, capturing even subtle gradations”.3

If time allowed before the delivery, parents were approached and their permission sought to record the resuscitation. If time did not allow, the recording was made and the parents approached as soon as practicable thereafter. Their permission was then sought to view the recordings and to use them for data extraction and educational purposes.

Pulse oximetry

Immediately after the infant was placed in the resuscitation cot the sensor of a pulse oximeter (Masimo Radical, Masimo Corporation, Irvine CA, USA) was placed around the right hand or wrist. The oximeter was set to acquire data with maximal sensitivity and average it over 2 s intervals. It was positioned near the infant so the heart rate and Spo2 values were recorded by the video camera.

Videos

Videos were used for this study if the infant's face (when not covered by a resuscitation mask), chest and abdomen were visible throughout and pulse oximetry data were obtained. Each video clip the clinicians were shown started with an infant's arrival on the resuscitation trolley and ended when either the infant's Spo2 was ⩾90% for more than 10 s or the infant was removed from the resuscitation trolley. When the clips were shown to the study participants, the oximetry readings were obscured, a clock timing the resuscitation was visible and no sound was audible. The maximum Spo2 value displayed for each infant during the selected clip was recorded.

What is already known on this topic

At birth, a newborn infant's need for and response to assistance is assessed clinically.

Determination of an infant's colour is an integral part of this assessment.

Assessment of colour

We invited medical and nursing staff from the neonatal intensive care unit to participate. They were screened for colour blindness using Ishihara colour charts (Toledo‐bend.com, http://www.toledo‐bend.com/colorblind/index.html). The video clips were shown on a large screen in a darkened room to three groups of participants using the digital video camera and a data projector. The ambient light conditions and display settings on the camera and data projector were identical for the three groups. The observers could not see one another's answer sheet. They were asked to indicate, for each video, whether the infant looked pink at the beginning, whether the infant became pink during the video or whether the infant never looked pink. If they judged the infant turned pink, they indicated the time on the clock when this occurred. The infant's Spo2 at this time was subsequently determined by the research team. Data were entered in a database and analysed using SPSS version 11.0 and Stata Release 8.2 software.

What this study adds

Clinicians often disagree whether or not an infant is pink.

When they agree, the oxygen saturation at which they perceive them to be pink varies widely.

Results

A total of 20 consecutive videos which fulfilled the selection criteria were shown. The infants had a mean (SD) birth weight and gestational age of 1552 (938) g and 31(4) weeks, respectively. Pulse oximetry data were available 66 (20) s after birth and clips were 205 (64) s long. Three infants received no respiratory support, two had free‐flow oxygen and the remaining 15 were given 100% oxygen using the Neopuff Infant Resuscitator (Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, Auckland, New Zealand). Nine infants were given either continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or positive pressure ventilation intermittently through a face mask (Laerdal, Victoria, Australia). Two others had nasal CPAP via a single nasal prong and four were intubated and ventilated. No infant received chest compressions or medications. Five infants were placed in polyethylene bags and the rest were dried with towels and placed under radiant heat. The Spo2 increased in all infants as the clips progressed.

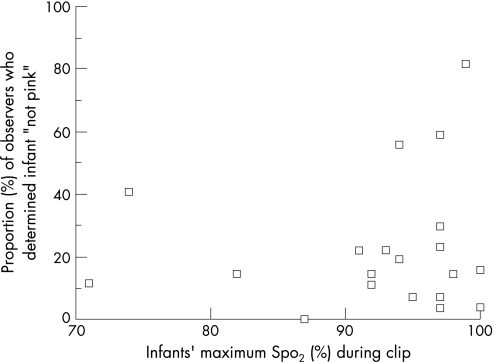

The 20 videos were assessed by 27 observers (7 neonatologists, 5 neonatal fellows, 1 paediatric registrar and 14 neonatal nurses). Only one (5%) infant was determined to be pink by all participants. This infant's highest Spo2 during the video clip was 87% (fig 1). For the other 19 infants, the number of observers who thought each infant never looked pink varied from 1 (4%) to 22 (81%). Observers determined the 10 infants with a maximum Spo2 ⩾95% never pink on 17% (46/270) of occasions.

Figure 1 Scatterplot showing the proportion (%) of observers who determined infants in 20 videos not pink according to the infants' highest oxygen saturation (Spo2) during the video clip.

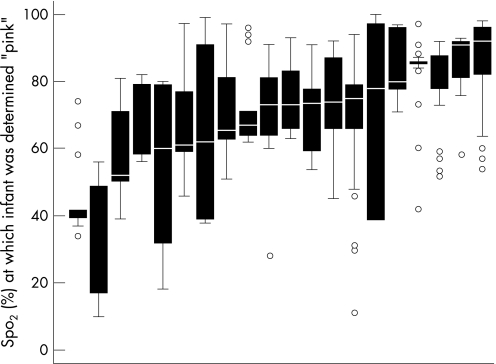

The mean Spo2 when infants were perceived to be pink by all 27 observers was 69% ranging from 10% to 100% between observers. The median Spo2 for individual babies varied from 42% to 93% (fig 2).

Figure 2 Boxplots showing median, interquartile range, outliers and extremes of oxygen saturation (Spo2) at which observers determined infants in 20 videos to be pink. Infants are ranked by increasing median Spo2 at which they were determined pink.

Discussion

We found substantial variation in the perception of newborn infants' colour among neonatal staff watching the same video recordings. Newborn infants' colour is used to assess the adequacy of their oxygenation in the delivery room. However, factors other than oxygenation influence an individual's colour. These include characteristics particular to the individual, such as skin thickness, skin colour, perfusion and haemoglobin concentration.4 Also, environmental factors such as ambient light5,6 affect colour perception. Infants in this study were from a variety of ethnic backgrounds, and were delivered at different gestations in varying ambient light conditions (eg, next to a delivery room window in daylight versus under fluorescent operating theatre lights at night). Although such factors may explain in part the variation in perception of colour between infants in this study, they do not explain why observers of the same video of the same infants disagreed about their colour to such a great extent. Differences between individuals' perception of colour have previously been shown.7,8 In our study each observer saw exactly the same information about each individual infant. We believe that the disagreement between observers of the colour the same infant is more important than the differences between infants, and that this finding in particular suggests that clinical assessment of the newborn infant's colour is unreliable. Variability in this assessment probably contributes to the variability reported in Apgar score assignment.9

While debate continues about how much oxygen to use when supporting infants at birth,1 the use of modifiable oxygen concentrations and pulse oximetry has been advocated for newborn preterm infants.10 A very wide range of Spo2 has been observed in healthy term and preterm infants in the minutes following birth.11,12,13 These values are in general lower than the Spo2 targeted in neonatal intensive care and increase with time. Among infants studied in neonatal intensive care, the correlation between the oxygen saturation determined by various pulse oximeters (Spo2) and that determined from blood gases (Sao2) was relatively poor when Sao2 was outside the range 92–97%.14 It is not clear how Spo2 values should influence the use of oxygen in the delivery room. However, the lack of agreement between observers whether infants were pink when Spo2 was ⩾90% suggests that clinical assessment may be an unreliable method to judge infants' oxygenation. Pulse oximetry may thus have a role in monitoring infants in the delivery room.

Conclusion

Observers of videos of newborn infants frequently disagreed whether the infants were pink and, when they agreed, the Spo2 at which they perceived infants to be pink varied widely. Clinical assessment of a newborn infant's colour may thus be unreliable. The role of pulse oximetry in the delivery room merits further evaluation.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Mark Davies for the mullet.

Abbreviations

Sao2 - arterial oxygen saturation

Spo2 - pulse oximeter oxygen saturation

Footnotes

Drs O'Donnell and Kamlin were in receipt of Royal Women's Hospital Postgraduate Degree Scholarships. Associate Professor Davis is in receipt of a National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) Practitioner Fellowship.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation The International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) consensus on science with treatment recommendations for pediatric and neonatal patients: neonatal resuscitation. Pediatrics 2006117e978–e988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldman H I, Maralit A, Sun S.et al Neonatal cyanosis and arterial oxygen saturation. J Pediatr 197382319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panasonic, ideas for life, Australia Digital Video Camera. http://panasonic.com.au/products/details.cfm?objectID = 2558 (accessed 25 June 2007)

- 4.Lundsgaard C, Van Slyke D D. Cyanosis. Medicine 192321–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelman G R, Nunn J F. Clinical recognition of hypoxaemia under fluorescent lamps. Lancet 196611400–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan‐Hughes J. Lighting and cyanosis. Br J Anaesth 196840503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comroe J H, Botelho S. The unreliability of cyanosis in the recognition of arterial anoxaemia. Am J Med Sci 19472141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medd W E, French E B, Wyllie V. Cyanosis as a guide to arterial oxygen desaturation. Thorax 195924714 [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Donnell C P, Kamlin C O, Davis P G.et al Interobserver variability of the 5‐minute Apgar score. J Pediatr 2006149486–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Heart Association Neonatal resuscitation textbook, 5th edn. Elk Grove IL: American Academy of Pediatrics 2006

- 11.Kamlin C O, O'Donnell C P, Davis P G.et al Oxygen saturation in healthy infants immediately after birth. J Pediatr 2006148585–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabi Y, Yee W, Chen S Y.et al Oxygen saturation trends immediately after birth. J Pediatr 2006148590–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mariani G, Dik P B, Ezquer A.et al Pre‐ductal and post‐ductal O2 saturation in healthy term neonates after birth. J Pediatr 2007150418–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerstmann D, Berg R, Haskell R.et al Operational evaluation of pulse oximetry in NICU patients with arterial access. J Perinatol 200323378–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]