Abstract

Cholecystokinin (CCK), released by lipid in the intestine, initiates satiety by acting at cholecystokinin type 1 receptors (CCK1Rs) located on vagal afferent nerve terminals located in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract. In the present study, we determined the role of the CCK1R in the short term effects of a high fat diet on daily food intake and meal patterns using mice in which the CCK1R gene is deleted. CCK1R-/- and CCK1R+/+ mice were fed isocaloric high fat (HF) or low fat (LF) diets ad libitum for 18 hours each day and meal size, meal frequency, intermeal interval, and meal duration were determined. Daily food intake was unaltered by diet in the CCK1R-/- compared to CCK1R+/+ mice. However, meal size was larger in the CCK1R-/- mice compared to CCK1R+/+ mice when fed a HF diet, with a concomitant decrease in meal frequency. Meal duration was increased in mice fed HF diet regardless of phenotype. In addition, CCK1R-/- mice fed a HF diet had a 75% decrease in the time to 1st meal compared to CCK1R+/+ mice following a 6 hr fast. These data suggest that lack of the CCK1R results in diminished satiation, causing altered meal patterns including larger, less frequent meals when fed a high fat diet. These results suggest that the CCK1R is involved in regulating caloric intake on a meal to meal basis, but that other factors are responsible for regulation of daily food intake.

Keywords: meal pattern analysis, cholecystokinin type 1 receptor, high fat diet

INTRODUCTION

The presence of nutrients in the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract modulates food intake through the release of regulatory peptides, such as cholecystokinin (CCK), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY) [1] and activation of the vagal afferent pathway [2]. It is well established that CCK functions as a satiety signal. CCK is released from enteroendocrine cells in response to the presence of lipid or protein in the gut [3]. Lipid, especially long chain fatty acids, is a particularly potent stimulator of CCK release [4]. CCK acts by binding to the CCK1R on vagal afferent nerve terminals located in the intestinal mucosa [5]. The vagal afferent fibers, with cell bodies located in the nodose ganglion, project to the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in the dorsal vagal complex, and from there, transmit information on meal content to the hypothalamus to terminate feeding [2,6]. Exogenous CCK was first shown to decrease food intake in rats in 1973 by Gibbs et al. [7], and since then has been shown to be effective in decreasing food intake in humans [8,9]. Duodenal nutrient infusion inhibits food intake in rats and this is reversed by administration of a CCK1 receptor antagonist, devazepide [10,11]. In addition, continuous intravenous infusion of devazepide increases ad libitum intake of chow in freely feeding rats, demonstrating a role for CCK and the CCK1R in the physiological regulation of food intake [12]. Despite this evidence that CCK plays a role in the regulation of food intake, mice lacking the CCK1R have normal daily food intake and normal body weight [13]. There is evidence that CCK1R-/- mice have altered meal patterns compared to wildtype controls on a standard rodent chow diet [14]. CCK1R-/- mice had significantly increased average meal size and decreased meal frequency compared to wild type mice; this is consistent with the known effects of CCK on food intake and short-term satiety.

It is well established that diet composition has a significant effect on food consumption. Ingestion of a high fat, high energy diet has been associated with increased food intake and weight gain compared to a low fat, high carbohydrate (LF) diets in laboratory animals [15] and in humans [16]. The changes in meal patterns that account for this overall increase in food intake may involve increases in meal size, meal duration or meal frequency. It remains unclear how CCK regulates free feeding of food containing various nutrient compositions. Little is known about how feeding behavior of CCK1R-/- mice is altered by diet composition. The CCK1R is involved in the detection of dietary lipid within the intestine in mice [17], but it is not clear whether these mice are able to respond to the satiating effects of lipid in the diet. We hypothesized that the CCK1R is involved in meal termination, particularly in the presence of high lipid content of the ingested diet.

The first aim of this study was to determine the changes in meal patterns in response to an increase in the amount of lipid in the diet in mice. Mice were fed either isocaloric low fat (10% fat, LF) or high fat (38% fat, HF) solid diets ad libitum for 18 hours a day and food intake was monitored continuously using cages with automatic feeders. The second aim of this study was to determine if the CCK1R is essential for the regulation of meal patterns during ingestion of either the LF or HF diet. To address this question, we used mice in which the gene for the CCK1R is deleted [13].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male CCK1R-/- mice (n=24) were used in all experiments. These mice were generously provided by Alan Kopin, MD, Tufts University School of Medicine. These mice are congenic with 129sv mice, which were used as wildtype controls. Aged matched 129Sv mice (8 weeks) (n=24) were obtained from Taconic (Oxnard, CA). All mice were individually housed on wire bottom cages and maintained on a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle (lights on at 3:00 am) at 23°C in a temperature-controlled room. Water was freely available throughout the experiments and body weight was recorded daily. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at University of California Davis.

Food intake analysis

Mice were maintained on either a high fat diet (HF; n=24) with 38% of energy fat derived from fat or a low fat diet (LF; n=24) with 10% of energy from fat. Diets were isonitrogenous (21% of energy) and isocaloric (3.4 kcal/g) (Table 1). Mice were fasted daily in wire bottom cages for 6 hours during the light cycle (9:00 am to 3:00 pm). Body weight was measured at 3 pm, prior to placement in the meal pattern analysis cages. Feeding patterns (meal frequency, meal duration, meal size, intermeal interval) were continuously measured daily from 3:00 pm to 9:00 am using food intake monitoring cages (The Habitest® System, Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA) delivering 20 mg pellets (Bioserv Custom Dustless Precision Pellets, Frenchtown, NJ). The pellet dispensers were controlled by infrared pellet-sensing photo beams; individual pellets were delivered in response to removal of the previous pellet.

Table 1.

Composition of experimental diets.

| Ingredients | LF (g/kg) | HF (g/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Corn Starch | 415 | 158 |

| Casein | 175 | 175 |

| Cellulose | 136 | 291 |

| Maltodextrin | 100 | 100 |

| Sucrose | 80 | 80 |

| Oil (Soy) | 38 | 140 |

| MM TD.79055 Ca-P defic. | 16 | 16 |

| CaHPO4 | 15 | 15 |

| Vitamin mix AIN-93G | 12 | 12 |

| CaCO3 | 7 | 7 |

| DL-Met or L-cys | 3 | 3 |

| Choline Bitatrate | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 1000 | 1000 |

Diets are isocaloric (3.4 kcal/g) and isonitrogenous (21% of energy).

LF diet contains 10% energy from fat and HF diet contains 38% of energy from fat.

Each experiment lasted 15 days. Mice were acclimated to the diets and the feeding paradigm for 5 days. By the end of the acclimation period, spillage was less than 8 pellets per mouse per day. Following the acclimation period, meal pattern data was recorded for 10 consecutive days.

Data analysis

Data was recorded from EZ count software and analyzed using Spike2 (version 5.07, Cambridge Electronic Design 1988-2004), SigmaStat (version3.11, Systat Software Inc. 2004) and Graph Prism® (version 3.02, GraphPad Software Inc. 1994-2000). The parameters were based on two previously published studies using mice [14,18]. A meal was defined as the acquisition of at least 4 pellets within 10 min, preceded or followed by 10 min of no feeding, as determined in preliminary studies. The meal parameters were optimized by adjusting meal size from 3 to 6 pellets per meal, while independently and/or simultaneously adjusting intermeal interval criteria from 5 to 30 minutes. Data from day 6 to day 15 was analyzed for the number of meals, meal size, intermeal interval, and meal duration. Due to occasional technical error with the feeders, a few data collection days were excluded from the final analysis. Days were chosen for analysis based on habitual total food intake. Generally, all mice in this study ate a minimum of 2 grams per day. Consequently, if the total daily food intake recorded was less than 1.5 grams, that entire day excluded from analysis. Based on these criteria, data from 5 individual days was randomly chosen for each mouse for additional data analysis. From these 5 randomly chosen days, every meal for each mouse was analyzed for size and duration, and average meal size, average intermeal interval, and average meal duration were calculated for each animal over the 5 days. Data for each mouse were averaged from the 5 randomly chosen days; this mean value was used to generate the average data for each group.

Statistical Analysis

A two-way ANOVA was performed with diet and strain as independent variables. All analyses were conducted using SigmaStat (version 3.11, Systat Software, Inc.). Differences among group means were analyzed using multiple comparison procedures (Holm-Sidak method) and considered significant if P<0.05.

RESULTS

Body weight

There was no difference in body weight between any of the groups at the start or at the end of the experimental period (Start of experiment: CCK1R+/+ 22.7 ± 0.9g, n=24, CCK1R-/- 22.5 ± 0.7g, n=24; End of experiement: CCK1R+/+ 20.6 ± 0.5g, n=24, CCK1R-/- 20.1 ± 0.8g, n=24).

Total food intake

There was no significant difference in daily food intake between any groups (total food intake: CCK1R+/+ LF and. HF diet; 5.4 ± 1.5g and 5.2 ± 1.4g, respectively; CCK1R-/- LF and HF; 4.9 ± 1.2g and 5.2 ± 1.4g, respectively, NS, n=24 per group).

Meal pattern analysis

Individual meals were analyzed for differences in meal duration, size and frequency, and intermeal interval. With the exception of the size of the first meal, there were no significant differences found for any parameter between individual meals for each animal over the course of each day, therefore values from all meals were meaned for each mouse and are presented as mean ± SEM.

Data from the first meal was analyzed separately as parameters differed significantly from all subsequent meals in all groups. The size of the first meal was larger in mice maintained on HF diet compared to LF diet, regardless of genotype. In CCK1R+/+ mice ingesting the HF diet, the 1st meal was 18% larger than mice ingesting LF diet although this did not reach significance (596 ± 50 mg vs. 705 ± 39 mg LF vs. HF, respectively, NS, n=24). In CCK1R-/- mice ingesting the HF diet, the 1st meal was 66% larger than in mice ingesting the LF diet (548 ± 45 vs. 907 ± 59 mg LF vs. HF, respectively, p<0.001).

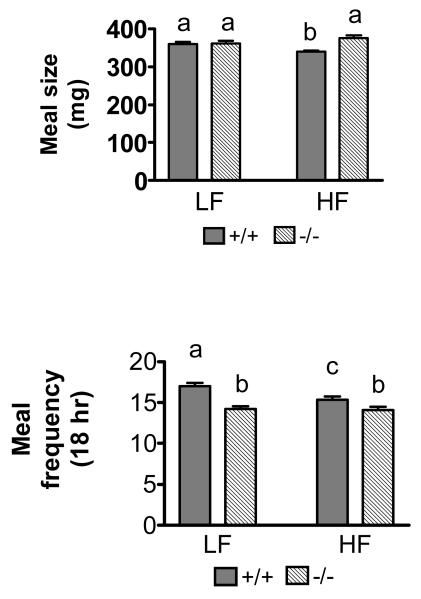

Meal size

Ingestion of the HF diet decreased meal size in wildtype mice, but had no effect on average meal size in CCK1R-/- mice (Fig 1a). There was a significant decrease in meal size in CCK1R+/+ mice when ingesting the HF compared to the LF diet (360 ± 6 mg vs. 339 ± 4 mg LF vs. HF, respectively, p<0.05). There was no difference in meal size in CCK1R-/- mice on the HF diet compared to the LF diet (meal size: LF: 362 ± 6 mg vs. 375 ± 8, LF vs. HF, respectively, NS). However, there was a significant effect of genotype on the meal size on the HF diet; meal size was increased by 10% in CCK1R-/- mice compared to CCK1R+/+ fed the HF diet. (p<0.05) (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

CCK1R-/- mice ate larger meals compared with CCK1R+/+ mice on HF diet. Genotype had no effect on meal size on LF diet. CCK1R-/- mice ate fewer meals compared with CCK1R+/+ mice on both HF and LF diet, whereas CCK1R+/+ mice ate 10% fewer meals on HF diet compared to LF diet. Data represent the average quantity of food ingested per meal over the entire 18 hours feeding period. (Values are means ± SEM, n=24 values with different letters denote significant difference between groups, p<0.05)

Meal frequency

There was a decrease in the number of meals in CCK1R+/+ mice fed the HF diet compared to the LF diet (Figure 1b); ingestion of the HF diet resulted in a 10% decrease in meal frequency compared to LF diet in CCK1R+/+ (p< 0.05). There was no difference in meal frequency in the CCK1R-/- mice on LF or HF diet. However, there was a significant genotype difference in meal frequency; CCK1R-/- mice ate significantly fewer meals compared to CCK1R+/+ mice, irrespective of diet (p< 0.001).

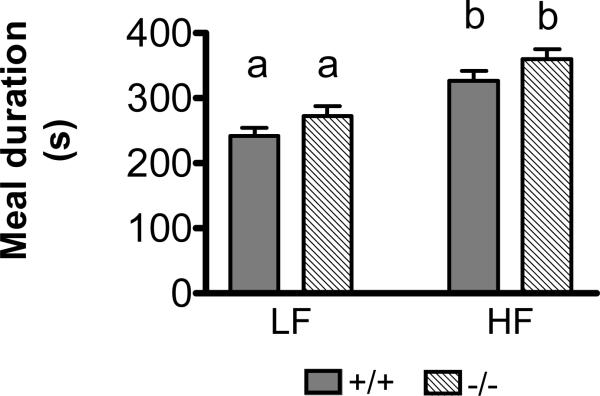

Meal Duration

Ingestion of the HF diet resulted in a significantly longer meal duration in both CCK1R+/+ and CCK1R-/- mice (Figure 2). Average meal duration was 35% longer in CCK1R+/+ mice on the HF diet compared to the LF diet (p<0.001). Similarly, average meal duration was 32% longer in CCK1R-/- mice on the HF compared to the LF diet (p<0.01). However, there was no effect of genotype on meal duration in mice fed either the LF or HF diet (NS) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

CCK1R-/- had a 32% longer average meal duration on the HF diet compared to the LF diet (p<0.01). CCK1R+/+ mice on HF diet had a 35% longer average meal duration compared to those fed the LF diet (n=24 per group, (p<0.001). There was no effect of genotype on average meal duration, regardless or diet. (NS, n=24)

Intermeal Interval

Diet composition or genotype had no significant effect on the average intermeal interval (IMI) (NS, n=24). IMI in CCK1R+/+ mice on LF and HF diet was 2116 ± 58s vs. 2242 ± 78s, respectively. Similarly, average IMI in CCK1R-/- mice on LF diet and HF diet was 2283 ± 73s vs. 2351 ± 86s. There was a tendency for the intermeal interval to be longer in the CCK1R-/- mice regardless of the diet on which they were maintained; however, this did not reach statistical significance.

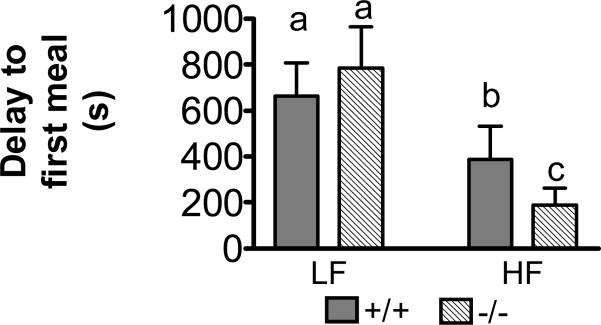

Delay to start of the first meal

The time to the start of the first meal was significantly decreased in CCK1R-/- mice fed the HF diet compared to the LF diet (Figure 3; p<0.05, n=24). There was also a 42% decrease in time to the first meal between LF and HF diet groups in the CCK1R+/+ mice. There was no significant difference between CCK1R+/+ mice and CCK1R-/- mice in the time to initiation of the first meal when mice were maintained on a LF diet (NS, n=24). However, there was a significant decrease in the time to the start of the first meal in the CCK1R-/- compared to the CCK1R+/+ mice on HF diet. Thus, the CCK1R-/- mice had 51% shorter time to 1st meal compared to CCK1R+/+ mice when fed the HF diet (p<0.05, n=24).

Figure 3.

CCK1R-/- mice on HF diet had significantly shorter latency to first meal compared to CCK1R+/+ mice and compared to -/- mice maintained on LF diet (p<0.05, n=24). There was no difference between -/- and +/+ on LF diet (NS, n=24).

DISCUSSION

The results from the present study demonstrate that the CCK1R is a major determinant in the regulation of meal patterns. Mice lacking the CCK1R ate larger and longer meals when ingesting a high fat diet compared to wildtype mice, while meal frequency was reduced such that daily food intake were unaffected. These data suggest that the absence of the CCK1R impairs the ability to terminate meals and support the hypothesis that both CCK and the CCK1R are involved in the determination of meal size. Thus, in normal mice, the presence of nutrients, in particular lipid when ingesting a HF diet, acts via release of CCK, and subsequent activation of CCK1Rs, to terminate a meal. In the absence of the CCK1R, detection of lipid in the intestinal lumen is reduced and there is diminished intestinal feedback regulation of meal size. As a result, the alteration of meal patterns in CCK1R null mice is more marked when ingesting a high fat diet, consistent with the role of the receptor in detection of lipid in the intestinal lumen [17]. However, overall daily food intake and intermeal interval remain unchanged, suggesting that other mechanisms regulate food intake over the course of several meals. Furthermore, these data also show that the CCK1R-/- mice ingesting the HF diet have significantly decreased latency to first meal after a short term fast. These data are consistent with increased hunger and urgency to feed and suggest a role for the CCK1R in meal initiation. Collectively, these results support the hypothesis that the CCK1R is essential for dietary lipid sensing within the intestine and normal meal patterning, especially when ingesting a HF diet.

The first aim of the study was to determine how dietary fat influences meal patterns in CCK1R+/+ mice. In order to determine the effect of lipid in the absence of increased caloric density of a high fat diet, we used isocaloric diets. There was no overall change in the total daily food intake, however, the daily pattern of ingestion was markedly altered. There was a significant decrease in meal size and an increase in meal duration in CCK1R+/+ mice ingesting the HF diet compared to the isocaloric LF diet; which is consistent with previous observations in rodents and humans [19,20]. In addition, there was a concomitant decrease in meal frequency in CCK1R+/+ mice fed the HF diet compared to the isocaloric LF diet. This is in accordance with other rodent studies that showed an inverse relationship between meal size and meal frequency [21,22]. Studies examining meal patterns have revealed that an increase in meal size results in a decrease in meal frequency [23,24].

Satiety is sometimes measured by the correlation between meal size or meal duration and intermeal interval. In the present study there was no significant correlation between IMI and meal size or meal duration. Although several labs have documented a correlation between meal size and postprandial intermeal interval [25-27], this concept has been disputed and remains controversial [28]. Additionally, other factors secreted by ingested food may act to extend the intermeal interval. Experiments using exogenous CCK injections found that CCK does not extend postprandial interval between meals [7,29,30], while bombesin and GRP do [31]. This indicates that CCK may be most influential in regulating satiation following the first meal, while additional factors could predominate subsequently.

The second aim of the study was to determine if the CCK1R is a major determinant of meal patterning in mice in response to dietary fat. Previous work has shown that the CCK1R is important in the regulation of food intake, but the role of the receptor in overall regulation of food intake has been hampered by limitations in the pharmacological tools available, particularly the duration of action of CCK1R antagonists. Experiments using rats have shown that continuous infusion of the CCK1R antagonist results in increase meal size [29]. Otsuka Long Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) rats, which lack the CCK1R, are hyperphagic due to an increase in meal size and an insufficient decrease in meal frequency to compensate for this increase in meal size [32]. The results from the present study show that the lack of the CCK1R reversed the decrease in meal size in response to HF diet, but had no effect on mice fed LF diet. This finding is inconsistent with the results observed by Bi et al. who showed that CCK1R-/- mice consumed 35% more chow per meal compared to wild-type mice [14]. However, this difference in meal size could be due to differences in diet composition, because CCK1 R+/+ mice ate smaller meals of HF diet compared to the mice fed LF diet, but CCK1R-/- mice ate the same size meals of LF and HF diet.

In addition, both groups of mice on the HF diet had significantly longer meal duration compared to mice fed the LF diet. These data suggests that, in CCK1R null mice, there is an inability to end meals and the mice fed HF diet eat larger meals over a longer time. It is well established that fat is a potent inhibitor of food intake via CCK release [33,34]. We conclude that in the absence of the CCK1R, the detection of the presence of dietary nutrients, notably fat, in the intestinal lumen is impaired and the pathway mediating intestinal feedback leading to satiation has been interrupted. It is possible that other satiety factors released from the GI tract and associated organs such as PYY, GLP-1 or amylin may act to terminate the meal; the time required for release of these other factors results in prolonged meal duration. Together, these results provide evidence that the CCK1R is required for regulation of meal size and intrameal satiation in mice. The onset of satiation is the major determinant of meal size, thus delaying satiation will cause an increase in meal size. Mice lacking the CCK1R may have larger meal size on HF diet due to faster gastric emptying time due to lack of lipid-induced intestinal feedback. Prior studies have shown more rapid gastric emptying in CCK1R-/- mice compared to wildtype controls [17].

One of the most striking findings in the present study was that CCK1R-/- mice ingesting a HF diet had significantly shorter latency to the start of the first meal after a 6 hour fast. This suggests that lack of the CCK1R reduces intrameal satiation, and additionally influences hunger. The association between CCK and initiation of feeding was established by Foltin and Moran who showed a dose dependent increase in the onset of feeding in adult male baboons using the CCK analog U-67827E [35]. The mechanism is unclear, but may involve orexigenic peptides, such as ghrelin or cannabinoids, both of which have been shown to increase hunger, and receptors for these peptides are expressed on vagal afferents [36,37]. It is likely that there is an intrinsic difference between wild type mice and those lacking the CCK1R in terms of receptor expression in the gut-brain pathway. It has been suggested that CCK modulates additional anorexigenic and orexigenic factors and it is probable that in the absence of the CCK pathway, expression of these factors or their receptors is altered [36].

CCK1R-/- mice ate fewer meals compared to CCK1R+/+ mice, irrespective of diet. This confirms previous results by Bi et al [14] who saw a slight decrease in meal frequency in CCK1R-/- mice fed standard rodent chow and other published data, as discussed above. The mechanism by which meal frequency is regulated remains unclear, but most likely involves other feeding peptides such as ghrelin. Degraaf et al. reported that exogenous administration of CCK decreased the stimulatory effects of ghrelin on meal size and meal initiation [38]. Additionally, it was reported that injection of sulfated CCK-8 blocked the orexigenic effect of ghrelin [39]. Consequently, it appears that the CCK1R pathway is involved with meal termination in response to HF diet, but does not directly regulate meal frequency. Interconnected with meal frequency, intermeal interval was also not changed by diet or phenotype, suggesting that other satiety factors such as leptin or PYY may be involved in regulating food intake over multiple meals. It has been previously reported that exogenous CCK decreased meal size without changing the duration of the intermeal interval [30]. Moreover, foraging studies using rats have shown little correlation between meal size and intermeal interval [28].

We observed no difference in total food intake in CCK R-/- mice compared to CCK1R+/+ mice regardless of diet. This is in accordance with previous studies have shown that there was no difference in 24 hour food intake between CCK1R-/- and CCK11+/+1 mice fed chow [13,14]. It is well established that rodents can regulate their caloric intake by eating less of a high calorie diet and more of a low calorie diet [40]. In the present study the caloric density was identical for both diets, which could account for the observation that total food intake was uniform across all groups.

Our results support the hypothesis that meal composition and the CCK1R are involved in regulating meal size. The present study provides evidence that CCK R1R-/- mice have decreased satiation compared to wild type mice when fed a HF diet. These results support the idea that the CCK1R is required for satiation, but has little effect on satiety in mice. It is evident that the ability to regulate body weight and energy balance over days and weeks is independent of the CCK1R in mice. It is well established that leptin and CCK act in synergy to reduce food intake and it has been shown that CCK enhances weight loss, but not the anorexic response to leptin [41]. Consequently, it is probable that normal expression of long term satiety signals such as leptin are responsible for the maintenance of normal body weight in the absence of the CCK1R.

CONCLUSIONS

While previous studies have shown that the CCK1R is involved in regulating short term food intake, no studies have examined the role of the CCK1R in 129sv mice in conjunction with feeding a high fat diet. In this study we have shown that mice lacking the CCK1R have diminished satiation causing altered meal patterns including longer, larger meals. Furthermore, we have shown that this reduction in satiation is accentuated by feeding a high fat diet. This effect is possibly due to diminished detection of dietary lipid within the intestine. Our results suggest that lipid detection in the CCK1R-/- mice may be impaired resulting in altered meal patterns. However, due to the action of other long term satiety peptides such as leptin and PYY these animals are able to maintain a normal body weight. The observed feeding patterns on HF diet suggest that the CCK1R is involved in regulating caloric intake on a meal to meal basis, and other factors are responsible for regulation over multiple meals.

Acknowledgements

Work funded by NIH DK41004. The authors are grateful to Alan Kopin, MD for the CCK type 1 receptor null mice.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Moran TH. Gut peptide signaling in the controls of food intake. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(Suppl 5):250S–253S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berthoud HR, Neuhuber WL. Functional and chemical anatomy of the afferent vagal system. Auton Neurosci. 2000;85:1–17. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liddle RA, Green GM, Conrad CK, Williams JA. Proteins but not amino acids, carbohydrates, or fats stimulate cholecystokinin secretion in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1986;251:G243–248. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1986.251.2.G243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaughlin JT, Lomax RB, Hall L, Dockray GJ, Thompson DG, Warhurst G. Fatty acids stimulate cholecystokinin secretion via an acyl chain length-specific, ca2+-dependent mechanism in the enteroendocrine cell line stc-1. J Physiol. 1998;513(Pt 1):11–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.011by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moran TH, Baldessarini AR, Salorio CF, Lowery T, Schwartz GJ. Vagal afferent and efferent contributions to the inhibition of food intake by cholecystokinin. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R1245–1251. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.4.R1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broberger C, Hokfelt T. Hypothalamic and vagal neuropeptide circuitries regulating food intake. Physiol Behav. 2001;74:669–682. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbs J, Young RC, Smith GP. Cholecystokinin decreases food intake in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1973;84:488–495. doi: 10.1037/h0034870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kissileff HR, Pi-Sunyer FX, Thornton J, Smith GP. C-terminal octapeptide of cholecystokinin decreases food intake in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:154–160. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieverse RJ, Jansen JB, Masclee AA, Lamers CB. Role of cholecystokinin in the regulation of satiation and satiety in humans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;713:268–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strohmayer AJ, Greenberg D. Devazepide increases food intake in male but not female zucker rats. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:273–275. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(96)83164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yox DP, Brenner L, Ritter RC. Cck-receptor antagonists attenuate suppression of sham feeding by intestinal nutrients. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:R554–561. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.4.R554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reidelberger RD, O'Rourke MF. Potent cholecystokinin antagonist l 364718 stimulates food intake in rats. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:R1512–1518. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.6.R1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kopin AS, Mathes WF, McBride EW, Nguyen M, Al-Haider W, Schmitz F, Bonner-Weir S, Kanarek R, Beinborn M. The cholecystokinin-a receptor mediates inhibition of food intake yet is not essential for the maintenance of body weight. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:383–391. doi: 10.1172/JCI4901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bi S, Scott KA, Kopin AS, Moran TH. Differential roles for cholecystokinin a receptors in energy balance in rats and mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3873–3880. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warwick ZS, Schiffman SS. Role of dietary fat in calorie intake and weight gain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1992;16:585–596. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lissner L, Levitsky DA, Strupp BJ, Kalkwarf HJ, Roe DA. Dietary fat and the regulation of energy intake in human subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;46:886–892. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/46.6.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whited KL, Thao D, Lloyd KC, Kopin AS, Raybould HE. Targeted disruption of the murine cck1 receptor gene reduces intestinal lipid-induced feedback inhibition of gastric function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G156–162. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00569.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powley TL, Chi MM, Baronowsky EA, Phillips RJ. Gastrointestinal tract innervation of the mouse: Afferent regeneration and meal patterning after vagotomy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R563–R574. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00167.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Synowski SJ, Smart AB, Warwick ZS. Meal size of high-fat food is reliably greater than high-carbohydrate food across externally-evoked single-meal tests and long-term spontaneous feeding in rat. Appetite. 2005;45:191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warwick ZS, McGuire CM, Bowen KJ, Synowski SJ. Behavioral components of high-fat diet hyperphagia: Meal size and postprandial satiety. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R196–200. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.1.R196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West DB, Fey D, Woods SC. Cholecystokinin persistently suppresses meal size but not food intake in free-feeding rats. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:R776–787. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.246.5.R776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathis CE, Johnson DF, Collier GH. Procurement time as a determinant of meal frequency and meal duration. J Exp Anal Behav. 1995;63:295–311. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1995.63-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clifton PG. Meal patterning in rodents: Psychopharmacological and neuroanatomical studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:213–222. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chi MM, Fan G, Fox EA. Increased short-term food satiation and sensitivity to cholecystokinin in neurotrophin-4 knock-in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1044–1053. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00420.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenwasser AM, Boulos Z, Terman M. Circadian organization of food intake and meal patterns in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1981;27:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies RF. Long-and short-term regulation of feeding patterns in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1977;91:574–585. doi: 10.1037/h0077335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas DW, Mayer J. Meal size as a determinant of food intake in normal and hypothalamic obese rats. Physiol Behav. 1978;21:113–117. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(78)90284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson DF, Ackroff K, Peters J, Collier GH. Changes in rats' meal patterns as a function of the caloric density of the diet. Physiol Behav. 1986;36:929–936. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miesner J, Smith GP, Gibbs J, Tyrka A. Intravenous infusion of ccka-receptor antagonist increases food intake in rats. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:R216–219. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.2.R216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strohmayer AJ, Smith GP. Cholecystokinin inhibits food intake in genetically obese (c57bl/6j-ob) mice. Peptides. 1981;2:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(81)80009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rushing PA, Henderson RP, Gibbs J. Prolongation of the postprandial intermeal interval by gastrin-releasing peptide1-27 in spontaneously feeding rats. Peptides. 1998;19:175–177. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(97)00274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moran TH, Bi S. Hyperphagia and obesity in oletf rats lacking cck-1 receptors. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361:1211–1218. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matzinger D, Gutzwiller JP, Drewe J, Orban A, Engel R, D'Amato M, Rovati L, Beglinger C. Inhibition of food intake in response to intestinal lipid is mediated by cholecystokinin in humans. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R1718–1724. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.6.R1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liddle RA, Goldfine ID, Rosen MS, Taplitz RA, Williams JA. Cholecystokinin bioactivity in human plasma. Molecular forms, responses to feeding, and relationship to gallbladder contraction. J Clin Invest. 1985;75:1144–1152. doi: 10.1172/JCI111809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foltin RW, Moran TH. Food intake in baboons: Effects of a long-acting cholecystokinin analog. Appetite. 1989;12:145–152. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(89)90103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burdyga G, Lal S, Varro A, Dimaline R, Thompson DG, Dockray GJ. Expression of cannabinoid cb1 receptors by vagal afferent neurons is inhibited by cholecystokinin. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2708–2715. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5404-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burdyga G, Varro A, Dimaline R, Thompson DG, Dockray GJ. Ghrelin receptors in rat and human nodose ganglia: Putative role in regulating cb-1 and mch receptor abundance. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G1289–1297. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00543.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Graaf C, Blom WA, Smeets PA, Stafleu A, Hendriks HF. Biomarkers of satiation and satiety. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:946–961. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobelt P, Tebbe JJ, Tjandra I, Stengel A, Bae HG, Andresen V, van der Voort IR, Veh RW, Werner CR, Klapp BF, Wiedenmann B, Wang L, Tache Y, Monnikes H. Cck inhibits the orexigenic effect of peripheral ghrelin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R751–758. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00094.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Treit D, Spetch ML. Caloric regulation in the rat: Control by two factors. Physiol Behav. 1986;36:311–317. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matson CA, Reid DF, Ritter RC. Daily cck injection enhances reduction of body weight by chronic intracerebroventricular leptin infusion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R1368–1373. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00080.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]