Abstract

Aim

A large longitudinal interventional study of patients with a urea cycle disorder (UCD) in hyperammonaemic crisis was undertaken to amass a significant body of data on their presenting symptoms and survival.

Methods

Between 1982 and 2003, as part of the FDA approval process, data were collected on patients receiving an intravenous combination of nitrogen scavenging drugs (Ammonul® sodium phenylacetate and sodium benzoate, 10%, 10%) for the treatment of hyperammonaemic crises caused by urea cycle disorders.

Results

A final diagnosis of a UCD was made for 260 patients, representing 975 episodes of hospitalisation. Only 34% of these patients presented within the first 30 days of life and had a mortality rate of 32%. The most common presenting symptoms were neurological (80%) or gastrointestinal (33%). This cohort is the largest collection of patients reported for these diseases and the first large cohort in the USA.

Conclusion

Surprisingly, the majority (66%) of patients with heritable causes of hyperammonaemia present beyond the neonatal period (>30 days). Patients with late-onset presenting disorders exhibited prolonged survival compared to the neonatal-presenting group.

Keywords: Drug treatment, hyperammonaemia, longitudinal study, survival, urea cycle disorders

INTRODUCTION

The urea cycle was first described in 1932 by Krebs and Henseleit1. The urea cycle disorders (UCDs) result from defects in the clearance of excess nitrogen produced by the breakdown of protein and other nitrogen-containing molecules. The incidence of these disorders in the United States is roughly estimated to be at least 1/25,000 births but partial defects may mean that this number is much higher2,3. In a Japanese study covering the period 1975-1995 the reported incidence was 1/46,000. Severe deficiency or total absence of activity of any of the first four enzymes in the urea cycle (carbamyl phosphate synthetase I, CPS-I; ornithine transcarbamylase, OTC; argininosuccinate synthetase, AS; argininosuccinate lyase, AL), or the cofactor producer N-acetyl glutamate synthase (NAGS), results in the accumulation of ammonia and other precursor metabolites during the first few days of life4. In milder (or partial) urea cycle enzyme deficiencies, hyperammonaemia may be triggered by illness or stress at almost any time of life, resulting in multiple mild elevations of plasma ammonia concentration5,6. In these cases the hyperammonaemias are less severe and the symptoms more subtle than in the patients with early-onset disease.

UCDs are considered a classic model for rare inborn errors of metabolism. Like many of these diseases, there are few patients at any particular treatment centre, and incidence and demographic data are sketchy at best. There has been a relative degree of uniformity in the treatment of acute episodes of hyperammonaemia in patients with UCDs during the past twenty years. This treatment involved the use of intravenous sodium phenylacetate and intravenous sodium benzoate as scavengers of excess nitrogen2. The open Investigational New Drug (number 17,123) study during this time (1982-2003) required enrollment of patients receiving intravenous drug for the treatment of an acute episode of hyperammonaemia. The study was limited primarily to patients with defects in the first three enzymes of the urea cycle (CPS-I, OTC, AS) with minimal inclusion of patients with arginase (ARG) deficiency or AL. As part of the FDA approval process a systematic chart review was done for these patients and data recorded on the presenting signs and symptoms, laboratory test parameters and any mortalities related to these hyperammonaemic incidents. This publication reports on the most comprehensive dataset in existence on these patients. Using this information we have developed statistics on the age of onset of disease for these patients, presenting symptoms, disease incidence for the first three enzyme defects of the urea cycle, and associated mortality rates. These data provide evidence-based insights into the nature of this particular group of rare disorders and challenge some of the assumptions typically made about these patients.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The data source for this study was an open-label, uncontrolled study in patients with hyperammonaemia due to UCDs. Data collected from 10 February 1982 through 31 May 2003 were included in the analyses for this article; the study was closed on 31 March 2005 after marketing approval for sodium phenylacetate and sodium benzoate (NaPA/NaBZ) injection 10%/10% (Ammonul®, Ucyclyd Pharma, Scottsdale, Arizona) was granted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Patients were originally treated under an Investigational New Drug application (IND number 17,123) sponsored, prior to 1999, by Dr. Saul W. Brusilow of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; the IND was transferred to Ucyclyd Pharma in 1999. Written informed consent, as appropriate for each institution, was obtained from each patient or their legal authorised representative. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained as appropriate at that time at the treating institutions. To the best knowledge of the authors and other experts in the field, this study was the only significant source of drug available to treat these patients during the period of 1982 to 2003.

The original protocol called for the treatment of patients with CPS-I, OTC or AS deficiency and not AL or ARG deficiency, and therefore the numbers for AL and ARG deficiency in this report do not reflect their true incidences in the patient population.

An episode was defined as a hospitalisation for hyperammonaemia during which the patient received NaPA/NaBZ Injection 10%/10% as rescue treatment. Data collected as part of the FDA study included plasma ammonia levels and presenting signs and symptoms. Episodes described herein occurred at 115 hospitals in the United States (U.S.) and Canada.

Data were collected on patients only during their time in hospital and no data were collected on these patients in the intervals when they were discharged from the hospital.

A specific urea cycle diagnosis was made for each patient by the treating physician. Acceptable diagnostic methods used included liver biopsy with enzymatic analysis (all disorders), mutation analysis (all disorders), allopurinol challenge test combined with hyperammonaemia and plasma amino acid analysis (OTC and CPS-I), plasma amino acid analysis (AS and AL), and erythrocyte assay (ARG).

Statistical Methods

The data presentation for this article consists of descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, and medians for continuous variables and frequency counts and percentages for categorical variables. Variation is reported as standard deviation. Missing data are excluded from the summaries and percentage calculations. Kaplan-Meier survival plots are also provided. Patients were censored at the hospital discharge date from the last episode experienced to avoid missing data errors. All data analyses were performed using SAS® (Cary, NC) version 8.2.

RESULTS

Three hundred sixteen patients were treated for 1045 episodes of hospitalisation between 1982 and 2003; however, 56 patients did not have definitive final diagnoses of a specific UCD and were thus not included in the analyses for this article. A final diagnosis of a UCD was made for 260 patients, representing 975 episodes of hospitalisation.

Patient Diagnoses and Age at Presentation

The most frequent diagnosis was OTC deficiency in 142 of 260 patients (55%), followed by AS deficiency (citrullinaemia I) in 70 patients (27%), CPS-I deficiency in 36 patients (14%), AL deficiency in 7 patients (3%), and ARG deficiency in 2 patients (<1%).

Fig. 1 shows the age of each patient at the first hospitalisation for hyperammonaemia, by each UCD diagnosis and by all diagnoses. Overall, the median age at first presentation was 2.0 years and ranged from 1 day to 53 years. Of the total of 260 patients diagnosed with a UCD, 34% were aged 0 to 30 days, 18% were aged 31 days to 2 years, 28% were aged >2 to 12 years, 10% were aged >12 to 16 years, and 10% were older than 16 years.

Figure 1.

Number of patients by diagnosis and age at first episode

Each patient is counted once at the age the first episode of hyperammonaemia was reported.

The typical age at first presentation varied among the different diagnoses. Males with OTC deficiency tended to present earlier (median of approximately 6 months) than females (median age of 10 years). Of 69 male patients with OTC deficiency, 46% presented at age 0 to 30 days, 19% at 31 days to 2 years, 22% at >2 to 12 years, and 13% at >12 years. As expected for this X-linked disorder, onset during infancy was the typical pattern; however, more than half of the males had late-onset OTC deficiency. Among the 73 female patients with OTC deficiency, onset during childhood or adolescence was the typical pattern, although only 4% presented at age 0 to 30 days, compared to 16% between the age of 31 days to 2 years, 51% at >2 to 12 years, 10% at >12 to 16 years, and 19% at >16 years.

For patients with CPS-I and AS deficiencies there was no typical age at first presentation. For both of these disorders the mean age of first presentation was during young childhood (median approximately 11 months) for CPS-I deficiency, and median of 2.0 years, for AS deficiency. Substantial percentages of patients had their first episodes at age 0 to 30 days (27% for CPS-I deficiency and 37% for AS deficiency), at 31 days to 2 years (30% for CPS-I and 14% for AS deficiency), and at >2 to 12 years (19% for CPS-I and 33% for AS deficiency).

For AL deficiency, 5 of 7 patients presented at age 0 to 30 days, 1 patient at 6 years, and 1 patient at 14 years, and for ARG deficiency, one patient presented at 3 days and the other at 19 years.

Recurrence of Hyperammonaemia

Fig. 2 shows the number of hyperammonaemic episodes by diagnosis and by age. Many patients had multiple episodes of hyperammonaemia, and thus, overall, the total number of hyperammonaemic episodes is far greater than the number of patients. For patients with AS or CPS-I deficiencies and males with OTC deficiency, approximately 70% of episodes occurred between the age of 31 days and 12 years. For females with OTC deficiency, 92% of episodes occurred at age >2 years.

Figure 2. Number of episodes by diagnosis and age at first episode.

Each patient with multiple episodes is counted multiple times at each age during which an episode of hyperammonaemia was reported.

Among patients with 5 or more reported episodes, the average number of episodes per year was 2.2 for patients with AS deficiency, 2.9 for males with OTC deficiency, 2.4 for females with OTC deficiency, and 2.8 for patients CPS-I deficiency. The number of episodes per year varied considerably among individual patients, ranging from 0.6 episodes per year in a patient with AS deficiency (9 episodes from the age of 3 to 17 years) to 8 episodes per year in a female with OTC deficiency (32 episodes from the age of 18 to 21). One patient with CPS-I deficiency had 8 hyperammonaemic episodes in the first year of life. The greatest number of episodes reported in any single patient was 77 in a female with OTC deficiency. She had an average of 3.5 episodes per year between the age of 2 and 23.

Signs and Symptoms of a Hyperammonaemic Episode in Patients with UCDs

Most hyperammonaemic episodes (58% of all episodes) were preceded by reported illness. Other known events preceding episodes included non-compliance with diet (15%), non-compliance with medication (10%), and major life events (such as surgery, accidents, school stress, pregnancy, etc) (10%).

Presenting signs and symptoms of a hyperammonaemic episode are summarised in Table 1. In the majority of episodes (76%) patients already had neurological symptoms at the time of hospital admission. A decreased level of consciousness (symptoms included fatigue, lethargy, drowsiness, unresponsiveness, coma, and obtundation), and/or abnormal motor function (symptoms included slurred speech, tremors, weakness, decreased or increased muscle tone, and ataxia), were more frequent at the first episode than at subsequent episodes. Altered mental status (symptoms included irritability, tantrums, strange behaviour or speech, dizziness, confusion, agitation, and combativeness) were slightly more frequent at subsequent episodes than at the first episode.

Table 1.

Frequency of presenting signs and symptoms

| Symptom | First Episode N=260 |

No. of Episodes Subsequent Episode N=715 |

Any Episode N=975 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any | 240 (92.3%) | 670 (93.7%) | 910 (93.3%) |

| Neurological | 208 (80.0%) | 532 (74.4%) | 740 (75.9%) |

| Decreased level of consciousness | 164 (63.1%) | 365 (51.0%) | 529 (54.3%) |

| Altered mental status | 83 (31.9%) | 268 (37.5%) | 351 (36.0%) |

| Abnormal motor function | 78 (30.0%) | 155 (21.7%) | 233 (23.9%) |

| Seizures | 25 (9.6%) | 34 (4.8%) | 59 (6.1%) |

| Other* | 17 (6.5%) | 65 (9.1%) | 82 (8.4%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 85 (32.7%) | 340 (47.6%) | 425 (43.6%) |

| Vomiting | 50 (19.2%) | 242 (33.8%) | 292 (29.9%) |

| Poor feeding | 24 (9.2%) | 75 (10.5%) | 99 (10.2%) |

| Diarrhoea | 9 (3.5%) | 58 (8.1%) | 67 (6.9%) |

| Nausea | 9 (3.5%) | 31 (4.3%) | 40 (4.1%) |

| Constipation | 0 | 9 (1.3%) | 9 (0.9%) |

| Other† | 13 (5.0%) | 73 (10.2%) | 86 (8.8%) |

| Co-morbid conditions | 118 (45.4%) | 299 (41.8%) | 417 (42.8%) |

| Infection | 75 (30.0%) | 252 (35.2%) | 330 (33.8%) |

| Respiratory | 16 (6.2%) | 57 (8.0%) | 73 (7.5%) |

| Renal | 17 (6.5%) | 12 (1.7%) | 29 (3.0%) |

| Cardiovascular | 10 (3.8%) | 3 (0.4%) | 13 (1.3%) |

| Haematological | 7 (2.7%) | 6 (0.8%) | 13 (1.3%) |

| Hepatic | 3 (1.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 4 (0.4%) |

| Other‡ | 15 (5.8%) | 27 (3.8%) | 42 (4.3%) |

| General/constitutional | 35 (13.5%) | 84 (11.7%) | 119 (12.2%) |

| Fever | 17 (3.5%) | 56 (7.8%) | 73 (7.5%) |

| Dehydration | 11 (4.2%) | 26 (3.6%) | 37 (3.8%) |

| Hypothermia | 5 (1.9%) | 1 (0.1%) | 6 (0.6%) |

| Weight loss | 2 (0.8%) | 2 (0.3%) | 4 (0.4%) |

| Failure to thrive | 0 | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Other§ | 2 (0.8%) | 3 (0.4%) | 5 (0.5%) |

| Routine check-up | 0 | 18 (2.5%) | 18 (1.8%) |

Includes headache, stroke, cerebral oedema, cerebral haemorrhage, cortical blindness, hemianopsia with scotoma, and burning eyes

Includes abdominal pain, gastritis, duodenitis, ileus, gastro-oesophageal reflux, gastrointestinal (GI) dysmotility, intestinal obstruction, irritable bowel syndrome, pancreatitis, GI bleed, duodenal atresia, gastroparesis, pyloric ulcer, and pyloric stenosis

Includes rash, fracture, burn, surgery, cholelithiasis, ovarian cyst, hernia, and necrosis of femoral heads

Includes hypovolaemia, paleness, puffiness, and oedema

Other notable presenting signs and symptoms included infection (reported in 34% of episodes) and vomiting (30%). Both sets of signs and symptoms were somewhat more frequent at subsequent episodes than at the first episode, particularly vomiting.

It should also be noted that in some patients (18 hyperammonaemic episodes), an elevated plasma ammonia level which received treatment was noted during a routine office visit and was not accompanied by symptoms typical of hyperammonaemia. In 9 of the 18 episodes for which hyperammonaemia was discovered during a routine office visit, no other symptoms were reported, while in the other 9 episodes, mild neurological symptoms such as irritability, drowsiness, or restlessness were noted during neurological examination but had not been reported previously. It is possible that in these circumstances the high levels of ammonia may reflect an artefact of specimen handling.

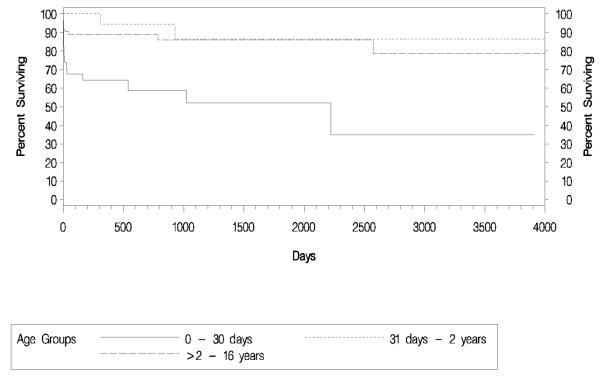

Survival of Patients with UCDs

Fig. 3 shows a Kaplan-Meier graph of survival by age at the first episode of hyperammonaemia. Survival time is calculated as the amount of time between the discharge date of the last episode and the admission date from the first episode. Patients who presented with the first hyperammonaemic episode at age between 0 and 30 days had the worst outcome - only 35% of patients were still alive at the final follow-up time point (approximately 11 years after the start of the study period). Of the 26 deaths that occurred in this group, 22 were within the first 2 months of life and only one patient after 3 years at the age of 6 years. Patients presenting in late infancy had the best outcome, with 87% remaining alive at the final follow-up time point. Only 2 patients in this group died, one at approximately 10 months of age and the other at approximately 2.5 years after the first episode. Of the patients presenting at >2 to 16 years of age, 78% were alive at the final follow-up time point. Ten of the 12 deaths in this group occurred within the first 50 days of initial presentation, one approximately 2 years later, and one approximately 7 years later.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival by age at first episode.

Fig. 4 shows a Kaplan-Meier graph of survival by diagnosis (data are not presented for AL and ARG) . Percent survival at the final follow-up time point was 78% among patients with AS deficiency, 74% among females with OTC deficiency, 61% among patients with CPS-I deficiency, and 53% among males with OTC deficiency. For all diagnoses, most deaths occurred within the first 2 months of initial presentation (16 of 20 deaths for males with OTC deficiency, 8 of 9 deaths for females with OTC deficiency, 4 of 7 deaths for patients with CPS-I deficiency, and 5 of 6 deaths for patients with AS deficiency.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival by diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

This report is the second large overview of data collected from the United States on the incidence of UCDs combined with clinical presentation and outcome data, and is the largest report on UCDs to date. These data also reflect the survival rates using the current treatment methods available for hyperammonaemic crisis (nitrogen scavenging compounds). These data are surprising in that they contradict the commonly held belief that UCDs are primarily disorders of the newborn period. As our data show, even when female OTC carriers are excluded the most common first presentation period for all diseases is outside the newborn period. The age distributions seen in these data contrast with the traditional view of UCDs as being primarily diseases of the newborn. Although 0 to 30 days was the most common age at first presentation, two-thirds of all patients had late-onset disease, and childhood (age 2 to 12 years) appears to be another vulnerable time period for the first hyperammonaemic episode. Accordingly, physicians caring for adults and older children should strongly consider a diagnosis of a UCD when confronted with the appropriate symptoms.

The data presented in this publication represent the original 316 patients and 1045 episodes of hyperammonaemia that were analysed for the US New Drug Application and that are described in the current Ammonul package insert. The data presented in a recent New England Journal of Medicine paper by Enns et al.7 used a slightly larger dataset of 389 patients and 1294 episodes of hospitalisation that were included in the safety update provided to the FDA at the time of the approval of the product. Analyses for both articles excluded patients without a diagnosis of a UCD. This manuscript uses this dataset to focus on the clinical presentations, morbidity and mortality rather than the acute response to drug. Slight differences between the two articles in survival are found because of the additional patients collected after the cutoff for this work.

It should also be noted that the highest mortality peaks for all disorders occur very close to the initial presentation. This suggests that there is a subset of patients that have such severe disease that they are resistant to therapy. Alternatively, delayed initial diagnosis and the consequent magnitude of hyperammonaemia may adversely affect the outcome of the initial hospitalisation for hyperammonaemia. Of the 43 deaths in these 260 patients, 27 occurred after the withdrawal of life support.

There was no strict definition of an elevated plasma ammonia level used in this study. It was the responsibility of the individual investigator to decide when treatment should be initiated. The investigator was asked only to check a box on the case report form noting whether the hyperammonaemic episode was preceded by illness, non-compliance with diet or medication, or major life event. A comments field allowed an investigator to report if the elevated plasma ammonia level was observed at a routine office visit and/or that the patient was asymptomatic.

The incidence data for the disorders targeted in this study group are very similar to those seen in the Japanese population in a study performed by Uchino et al3 on 216 cases. The biggest discrepancies were fewer males with OTC deficiency in the U.S. data (26% vs 43%) and more patients with AS deficiency (27% vs 11%). This may reflect detection and reporting rates of different disorders although similar laboratory methods are used. There has not been a report of a common mutation for either disease in either population at this time so we cannot account for it in this regard. Since the majority of these studies were performed before the advent of expanded newborn screening, there should not be a detection difference based purely on methodology.

The survival data from this study are more encouraging than the commonly held opinion might be for these disorders. In all disease groups, at least 50% of the patients were alive at 5 years. Mortality seems to correlate closely with age at presentation, with the newborn group having the lowest survival statistics. These data also justify the consideration of alternative therapies such as orthotopic liver transplantation in those enzyme deficiencies such as OTC and CPS-I that present in the neonatal period.

For the clinical presentation of these patients it was expected and confirmed that neurological signs would be the most common presenting feature. It was surprising that only 63% of patients had a reported decreased level of consciousness at the first episode and only 19% presented with vomiting. A decreased level of consciousness (symptoms included fatigue, lethargy, drowsiness, unresponsiveness, coma, and obtundation), and/or abnormal motor function (symptoms included slurred speech, tremors, weakness, decreased or increased muscle tone, and ataxia), were more frequent at the first episode than at subsequent episodes. This may be because patients were younger at the first episode, or because treatment was sought sooner at subsequent episodes (after a definitive diagnosis had been established), before more severe symptoms such as coma and ataxia had developed.

Altered mental status (symptoms included irritability, tantrums, strange behaviour or speech, dizziness, confusion, agitation, and combativeness) were slightly more frequent at subsequent episodes than at the first episode. Such symptoms may be more frequent among older patients, or may have been reported less frequently at the first episode because they were overshadowed by more serious symptoms such as coma and ataxia.

The high incidence of infection (34%) as a co-morbid condition underscores the importance of careful “sick-day” monitoring and treatment of these patients. Moreover, these data support the long-time anecdotal observation that catabolic stress, e.g., from a viral illness, is a more significant risk factor for hyperammonaemia than an increased dietary intake of nitrogen.

These data may not contain all of the presenting symptoms of these patients, but a careful review of each medical record was made to extract the data.

The low frequency of patients with AL deficiency (argininosuccinic aciduria) differs from other reports; however, as described in the methods, these patients were not included in the original study design for treatment.

In summary, UCDs represent a model for studies of the incidence and prevalence of rare inborn errors of metabolism. The NIH has sponsored a long term in-depth longitudinal study of these patients to answer many of the questions about neurological development, survival, quality of life, and growth that are not answered in this study. More information about this study and an enrollment site for patients can be found at: http://rarediseasesnetwork.epi.usf.edu/ucdc/index.htm.

Acknowledgments

B.L. and M.S. are supported by the Rare Disease Clinical Research Center Urea Cycle Grant (RR19453-01), B.L. is supported by R01 DK54450 and Baylor College of Medicine Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Center (MRDDC). We would like to thank David Varnam for the excellent editing work in this manuscript. We would like to thank Erin Glynn and Joe Mauney for their help in database and statistical work.

Footnotes

The authors do not have a financial conflict of interest in the publication of this material.

References

- 1.Krebs HA, Henseleit K. Untersuchungen uber die harnstoffbildung im tierkorper. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z Physiol Chem. 1932;210:325–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brusilow SW, Maestri NE. Urea cycle disorders: diagnosis, pathophysiology, and therapy. Adv Pediatr. 1996;43:127–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uchino T, Endo F, Matsuda I. Neurodevelopmental outcome of long-term therapy of urea cycle disorders in Japan. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21(Suppl 1):151–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1005374027693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Summar M. Current strategies for the management of neonatal urea cycle disorders. J Pediatr. 2001;138(1 Suppl):S30–9. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith W, Kishnani PS, Lee B, et al. Urea cycle disorders: clinical presentation outside the newborn period. Crit Care Clin. 2005;21(4 Suppl):S9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Summar ML, Barr F, Dawling S, et al. Unmasked adult-onset urea cycle disorders in the critical care setting. Crit Care Clin. 2005;21(4 Suppl):S1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enns GM, Berry SA, Berry GT, Rhead WJ, Brusilow SW, Hamosh A. Survival after treatment with phenylacetate and benzoate for urea-cycle disorders. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(22):2282–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]