Abstract

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Ibudilast is an oral drug approved in Asia for asthma.

Tolerability of 10-mg regimens has been described previously.

Published pharmacokinetics (PK) are limited: single or 7-day repeat oral administration of 10 mg in healthy male Asian volunteers.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Safety/tolerability and PK of a single 30-mg dose and a 30-mg twice daily (b.i.d.) 2-week regimen in male and female healthy volunteers.

Higher-dose regimens are relevant for testing in new neurological indications.

LC-MS/MS analytics for quantification of plasma and urine levels of ibudilast parent and its primary metabolite (6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast).

AIMS

To investigate the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics (PK) of ibudilast after a single-dose and a multiple-dose regimen.

METHODS

Healthy adult male (n = 9) and female (n = 9) volunteers were evaluated over a 17-day stay in a Phase 1 unit. Subjects were randomized 1 : 3 to either oral placebo or ibudilast at 30-mg single administration followed by 14 days of 30 mg b.i.d. Complete safety analyses were performed and, for PK, plasma and urine samples were analysed for ibudilast and its major metabolite.

RESULTS

Ibudilast was generally well tolerated. No serious adverse events occurred. Treatment-related adverse events included hyperhidrosis, headache and nausea. Two subjects discontinued after a few days at 30 mg b.i.d. because of vomiting. Although samples sizes were too small to rule out a sex difference, PK were similar in men and women. The mean half-life for ibudilast was 19 h and median Tmax was 4–6 h. Mean (SD) steady-state plasma Cmax and AUC0–24 were 60 (25) ng ml−1 and 1004 (303) ng h ml−1, respectively. Plasma levels of 6,7- dihydrodiol-ibudilast were approximately 30% of the parent.

CONCLUSIONS

Ibudilast is generally well tolerated in healthy adults when given as a single oral dose of 30 mg followed by 30 mg b.i.d. (60 mg day−1) for 14 days. Plasma PK reached steady state within 2 days of starting the b.i.d. regimen. Exposure to ibudilast was achieved of a magnitude comparable to that associated with efficacy in rat chronic pain models.

Keywords: human volunteers, ibudilast, pharmacokinetics, Phase 1, safety, tolerability

Introduction

Chronic neuropathic pain such as that associated with diabetic neuropathy can be a severe and disabling disorder that typically presents as spontaneous pain, hypersensitivity, burning, tingling and other unpleasant sensations. Ibudilast (3-isobutyryl-2-isopropylpyrazolo-[1,5-a]pyridine) is a Japanese oral drug that has been registered and used in Asia for > 15 years for the treatment of asthma and, more recently, for post-stroke dizziness. Although ibudilast is known to be a relatively nonselective phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitor, it has been discovered that another aspect of its pharmacology, i.e. glial cell regulating activity, may enable its use for the treatment of neuropathic pain [1, 2]. Glial cells (microglia, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes) have been shown to play a key role in neuropathic pain in animal models, at least in part via proinflammatory cytokine release [3]. For example, administration of the glial-regulating and anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-10, can result in long-term, significant attenuation of neuropathic pain in standardized animal models of this condition [4]. Alternatively, systemic administration of ibudilast is well-tolerated, attenuates glial cell activation in the central nervous system (CNS), and attenuates mechanical allodynia in several rat models of neuropathic pain [2]. More recently, animal pharmacology studies have yielded support for the utility of ibudilast in opioid withdrawal, wherein glial activation may contribute to tolerance and dependence [5]

Apart from its glial-attenuating activity, ibudilast has some attractive ‘drug-like’ features, including low molecular weight (230 D), good CNS partitioning (2) and reportedly acceptable oral pharmacokinetics (PK) in humans [6]. Moreover, according to the Japanese package inserts for the marketed delayed release capsule forms, Ketas® and Pinatos®, ibudilast appears to have an excellent tolerability and safety profile at approved dose levels of 10 mg administered twice or thrice daily (20 or 30 mg day−1).

To our knowledge, ibudilast (‘AV411’ by Avigen designation) has not been previously evaluated in a classic Phase 1 protocol except for studies confined to Asian men with dosing over ≤8 days and at doses no greater than 30 mg day−1[6, 7]. Based on preclinical work [2], previous human PK data [6, 7] and preliminary assessments of exposure–response relationships in patients [8], we predict that pain relief in patients is likely to require doses greater than those approved and currently used for asthma and other conditions in Asia (i.e. >30 mg day−1). Hence, the purpose of this study was to investigate the safety, tolerability and PK of a ‘higher-dose’ regimen. Here, we present findings for ibudilast in male and female subjects (predominately White) in a Phase 1, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study with single oral doses of 30 mg followed by oral doses of 30 mg b.i.d. (60 mg day−1) for 14 days.

Methods

Study population and design

The study was of double-blind and placebo-controlled design. The planned enrolment was 16 healthy subjects (eight male and eight female), aged 18–70 years. Subjects were randomized to receive ibudilast or placebo in a 3 : 1 ratio in blocks of four with separate randomization schedules for men and women; hence 12 subjects were to receive ibudilast (six male and six female) and four were to receive placebo (two male and two female). Subjects who withdrew from the study could be replaced. The trial was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Royal Adelaide Hospital (Adelaide, South Australia, Australia) and was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practices for Trial of Medicinal Products, as well as the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. All subjects gave their written informed consent before participation in the study.

Male and female subjects of any ethnic group were eligible for participation, provided they were able to provide written informed consent and met the following criteria: nonsmoking; 18–70 years old, no clinical abnormality (in the investigator's clinical judgment) in the laboratory and urine analyses; normal renal function with glomerular filtration rate >90 ml min−1; liver enzymes less than twice the upper limit of normal; screening ECG with QT interval adjusted for heart rate within normal limits in the investigator's clinical judgment. Furthermore, all subjects had to agree to use barrier contraceptive methods during the course of this study (hormonal contraceptive alone was not acceptable) and female subjects of child-bearing potential had to have a negative pregnancy test on study day 1. The occurrence of the following prevented study enrolment, warranting exclusion: known hypersensitivity to Pinatos® (ibudilast or excipients); conditions that might affect drug absorption, metabolism or excretion; untreated mental illness, current drug addiction or abuse or alcoholism; blood donation in the past 90 days or poor peripheral venous access; platelets <100 000 mm−3 and/or a history of thrombocytopenia; confirmed diagnosis of chronic liver disease, e.g. chronic hepatitis B, hepatitis C infection, autoimmune disease, alcoholic or neoplastic liver disease; positive for human immunodeficiency virus; pregnant or nursing mother; history of clinically significant cardiovascular, pulmonary, endocrine, neurological, metabolic or psychiatric disease; receipt of an investigational drug in the past 30 days; or inability to swallow large capsules.

Subjects were resident in a clinical research unit for the study duration. A single administration of 30 mg was administered on day 1 followed by 14 days of b.i.d. dosing beginning on day 3. Standard meals were served at 07.00, 12.00 and 18.00 h and were given at least 1 h before dosing at approximately 08.00 and 20.00 h.

Drug

The study used a generic delayed-release ibudilast product, Pinatos®, which was obtained from the Japanese manufacturer, Taisho Pharmaceuticals Industries, Ltd (Koka, Japan) and produced under Japanese current Good Manufacturing Practice guidelines. In order to blind the drug product, over-encapsulation was performed using Swedish-orange capsules. The critical release analytical procedures (Japanese marketed product release criteria) were repeated on the over-encapsulated drug product. Visual placebos were produced by over-encapsulating white capsules filled with mannitol. Each capsule of drug product contained 10 mg of ibudilast and additives inherent to the Pinatos® product, some of which prolong dissolution of ibudilast in the human gastrointestinal tract.

Clinical safety assessments

Adverse events were coded using the MedDRA Version 9.0 coding dictionary. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were defined as adverse events that started after the first dose of study drug or worsened in intensity after the first dose of study drug.

Blood sampling for haematology and chemistry were drawn at screening, day 1, day 6, day 10 (haematology only), day 13 (haematology only), day 16, day 20 and at a follow-up visit, 90 days after the last dose. Urinalysis was performed on the same days as the blood except for days 10 and 13.

Vital signs were assessed at screening and in the morning (before taking study medication when it was a dosing day) on each day from day 1 to day 17 and again on day 20. A 12-lead ECG was obtained at screening, day 1 (predose and 4 h post dose), day 6 and day 16 (before the morning dose and 4 h after the evening dose) and day 20.

Pharmacokinetics

Blood samples for ibudilast and its primary metabolite (6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast) were drawn on day 1 predose and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 24, 32 and 48 h after dosing; predose on day 5; on day 6 predose (at 0 h) and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16 and 24 h after the morning dose; predose on days 10 and 13; on day 16 predose (at 0 h) and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 22, 26 and 32 h after the morning dose; and a final sample drawn in the morning of day 20. On each occasion, a 2-ml volume of blood was drawn into a K2 ethylenediamine tetraaceticacid vacutainer tube; blood was promptly processed into plasma by centrifugation in a refrigerated unit. Urine samples were collected from 0 to 8 h and from 8 to 16 h after the morning dose on day 1, day 6 and day 16. Plasma samples and urine specimens were collected for assay of ibudilast and its metabolite and stored frozen at approximately −70°C.

For each subject, the PK variables were calculated by noncompartmental methods from the plasma concentrations of ibudilast and 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast. The following PK variables were calculated for day 1 (after a single dose): (i) maximum concentration (Cmax); (ii) time of the maximum concentration (Tmax); (iii) area under the curve during the dosing interval (AUCτ); (iv) area under the curve from the time of dosing to 24 h after dosing (AUC0–24); (v) area under the curve from the time of dosing extrapolated to infinity (AUC0–∞); and (vii) terminal half-life (t1/2). The following PK variables were calculated for day 6 and day 16 (after multiple doses): (i) Cmax at steady state (Cmax,ss); (ii) Tmax at steady state (Tmax,ss); (iii) minimum concentration at steady state (Cmin,ss); (iv) AUCτ at steady state (AUCτss); (v) AUC0–24 at steady state (AUC0–24ss); and (vi) t1/2 (day 16 only). The following three accumulation ratios were calculated for day 6/day 1, day 16/day 1 and day 16/day 6:

RA1 = Cmax,ss/Cmax

RA2 = AUCτss/AUCτ

RA3 = AUCτss/AUC0–∞

Bioanalytics

Plasma and urine samples were evaluated for ibudilast using a bioanalytical method that was validated in accordance with Food and Drug Administration guidance [9]. To prepare the samples for analysis, ibudilast and the corresponding internal standard (AV1040, a structurally-related ibudilast analogue with a favourable fractionation pattern) were isolated from plasma and urine by addition of 0.2% formic acid in acetonitrile. Centrifugation was used to isolate the supernatant fraction. The supernatant fractions were analysed by high-performance liquid chromatography (LC) in conjunction with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer that used electrospray ionization in tandem with positive ionization (MS/MS) under the following LC-MS/MS conditions:

Analytical column: Fluophase RP, 2.1 × 50 mm, 5 µm

Temperature: 35°C.

Mobile phase (A): 0.2% formic acid in water

Mobile phase (B): 0.2% formic acid in acetonitrile

Mass spectrometer: Sciex API 5000 with Turbo Spray Source, electrospray ionization positive injection volume: 10 µl

Gradient

| Time | Flow | A | B |

|---|---|---|---|

| (min) | (µl/min) | (%) | (%) |

| 0.00 | 450 | 75 | 25 |

| 0.50 | 450 | 75 | 25 |

| 2.50 | 450 | 5 | 95 |

| 4.00 | 450 | 5 | 95 |

| 4.01 | 450 | 100 | 0 |

| 4.50 | 450 | 100 | 0 |

| 4.51 | 450 | 75 | 25 |

| 6.50 | 450 | 75 | 25 |

The accuracy was 100 ± 10%, the precision was ≤10% (SD/mean) and the lower limit of quantification was 1.00 ng ml−1.

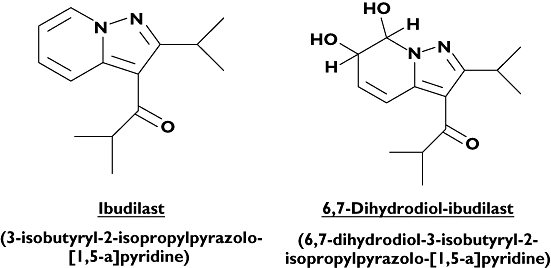

In addition to measuring ibudilast, the LC-MS/MS assay was used to analyse plasma and urine samples for 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast (Figure 1). Because chemical synthesis of the metabolite was not possible, it was purified from rat and rabbit liver. As only a small amount of 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast was obtainable, the purified material was used to compare the LC-MS/MS signals for ibudilast and the metabolite. The results showed that the calibration curves for the two molecules were reproducibly parallel over concentrations ranging from 1 to 1000 ng ml−1. The mean ratio of the two curves was used to estimate a ‘correction factor’ multiplier used to deduce concentrations of 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast from ibudilast calibration curves.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of ibudilast and its major oxidative metabolite, 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast

Statistical analyses

Descriptive and inferential statistics were performed using SAS release 8.02 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). For continuous variables, the summary statistics of N, geometric mean, arithmetic mean (referred to as ‘mean’), standard deviation about the arithmetic mean (SD), median, minimum and maximum were used. Where change from baseline was evaluated, baseline was defined as the last measurement before the first dose of study drug; the baseline mean for those subjects with change from baseline data at each time point was also evaluated. For categorical data, the number and percentage were used in the data summaries. No imputations were made for missing data.

PK parameters were derived by noncompartmental analysis using WinNonlin 5.0.1 (Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA, USA). All PK parameters were calculated on an individual subject basis. Summary statistics were calculated for each profile day [after a single dose on day 1 (30 mg) and after multiple doses on day 6 and day 16 (30 mg, b.i.d.)]. All plasma and urine concentrations determined to be <1.00 ng ml−1[below the quantifiable limit (BQL) for ibudilast and 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast] were substituted to half the limit of quantification (0.50 ng ml−1) for the calculation of the descriptive statistics of the concentrations and for use in the plasma concentration–time profiles, except at 0 h, where the concentration was taken as zero. All BQL values in the terminal phase or between two quantifiable concentrations were excluded from the PK variable calculations except at time points before the Cmax, where such data were to be taken as zero. AUCs were calculated by the logarithmic-linear (log-linear) trapezoidal method. For parameters derived through estimation of the terminal slope (t1/2 and AUC0–∞), linear regression was performed of the logarithm of plasma concentration vs. time during the apparent elimination phase.

Results

Disposition of subjects and demographics

Of the 18 healthy volunteers who were randomized, four subjects (all of whom received ibudilast) did not complete the study to day 20. Of these four subjects, two were withdrawn by the investigator because of nausea and vomiting and two withdrew for nonstudy-related reasons and were replaced by subjects assigned to the ibudilast treatment.

In terms of demographics, the mean age of all subjects (ibudilast and placebo groups) was 29.3 (SD 11.6) years and the median age of subjects in the ibudilast group was the same in the placebo group, 25 years. The male : female ratio was 1 : 1, as expected by the randomization sequence. Mean height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were similar in both groups (height 174 and 177 cm for ibudilast and placebo groups; weight 77 and 78 kg, respectively; BMI 25 for each). Ethnic background was predominantly White (11% Asian).

Safety

TEAEs were of mild to moderate intensity, and incidence (Table 1) was similar in both the ibudilast group [12 (85.7%) subjects] and the placebo group [three (75.0%) subjects]. Nine (64.3%) of the subjects from the ibudilast group and one (25%) subject from the placebo group had TEAEs of moderate intensity, whereas the remainder of subjects had TEAEs considered mild. The three most frequently reported TEAEs were experienced in subjects from both groups; these were as follows: hyperhidrosis [seven (50%), two (50%) subjects, respectively], headache [six (42.9%), one (25.0%) subjects, respectively] and nausea [three (21.4%), one (25.0%) subjects, respectively]. The TEAEs of nausea [three (21.4%) subjects] and vomiting [two (14.3%) subjects] that were considered to be possibly or probably related to study medication were all (with the exception of one subject with nausea in the placebo group) reported by subjects from the ibudilast group. Two women in the ibudilast group discontinued study medication because of several vomiting incidents in the first few days of b.i.d. dosing. As nausea has been associated with ibudilast (Ketas® and Pinatos® Package Inserts), this TEAE was not unexpected. There were four subjects (28.6%) from the ibudilast group with single episode headaches that were considered to be possibly or probably related to study medication and none from the placebo group.

Table 1.

Adverse events

| Ibudilast (n = 14)n (%) | Placebo (n = 4)n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Possibly or probably related to study medication | Total | Possibly or probably related to study medication | |

| Number of subjects experiencing a TEAE | 12 (85.7) | 11 (78.6) | 3 (75.0) | 2 (50.0) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 7 (50.0) | 7 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) |

| Hyperhidrosis* | 7 (50.0) | 7 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 5 (35.7) | 4 (28.6) | 3 (75.0) | 2 (50.0) |

| Nausea | 3 (21.4) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) |

| Vomiting | 2 (14.3) | 2 (14.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) |

| Diarrhoea | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (25.0) | 0 |

| Stomach discomfort | 0 | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 0 |

| Nervous system disorders | 6 (42.9) | 4 (28.6) | 1 (25.0) | 0 |

| Headache | 6 (42.9) | 4 (28.6) | 1 (25.0) | 0 |

| Disturbance in attention | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Tremor | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Infections and infestations | 3 (21.4) | ND | 0 | 0 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 2 (14.3) | ND | 0 | 0 |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Leukopenia | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| General disorders and admin. site conditions | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Feeling abnormal | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Investigations | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase increased | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 |

Excessive sweating. Percentages are based on the number of subjects in the Safety Set. ND, not determined. TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Assessment of the haematology and serum chemistry data at the treatment level showed that the mean changes from baseline at various time points were small and inconsistent, with no marked differences between the ibudilast and placebo groups. Whereas laboratory tests showed a weak trend for increases in mean alkaline phosphatase (ALP) values in the ibudilast group, all values remained in the normal range. In one subject, leukopenia considered possibly related to study medication was reported on day 13. However, the baseline white blood cell count (WBC) was 4.35 × 109 l−1 (close to the lower limit of the reference range of 4 × 109–11 × 109 l−1), yet 3.88 × 109 l−1 on day 1 and then on day 13 it was 3.69 × 109 l−1 and normal again at 4.13 × 109 l−1 on day 16. Another subject had an increase of γ-glutamyl transferase value at day 16 to 78 U l−1 from a baseline of 60 U l−1 that was considered to be clinically significant and possibly related to study medication. Another subject's urine was normal at baseline, but on day 20 the subject's urine had a WBC urinary count of 40 µl−1 and a red blood cell urinary count of 20 µl−1. This was asymptomatic, and on day 23 a repeat urinalysis was normal. Urinalysis abnormalities were recorded as TEAEs and considered unrelated to study medication.

In terms of vital sign measurements, no consistent changes from baseline were observed in blood pressure, temperature, respiratory rate or pulse. On the basis of the 12-lead ECG analysis, there were no changes relative to baseline in waveform morphology or interval duration measurements.

Pharmacokinetics

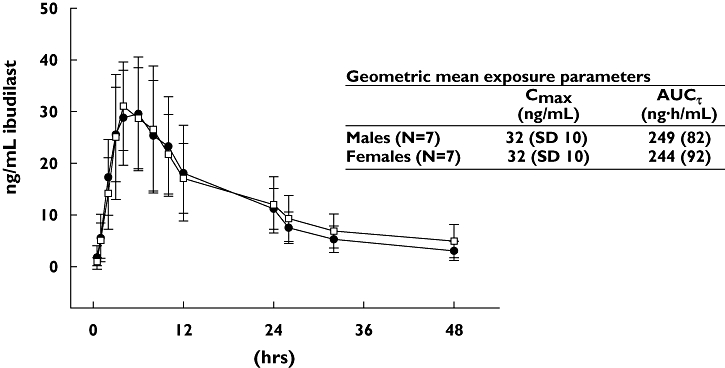

The ibudilast concentration–time plots for men and women (Figure 2) show that the PK profiles were essentially the same in the two sexes; thus, the data from this study suggest that sex may not be an important determinant of ibudilast PK. Because of the apparent lack of an important difference between the sexes, the concentration–time plots and PK parameters for men and women were combined to assess trends in the data and to compute the summary statistics (geometric means and SDs).

Figure 2.

Mean plasma concentrations of ibudilast in men and women. Plasma concentration vs. time profile of Ibudilast following a single 30-mg oral dose from n = 7 men (•) and n = 7 women (□). Data presented are mean (± SD)

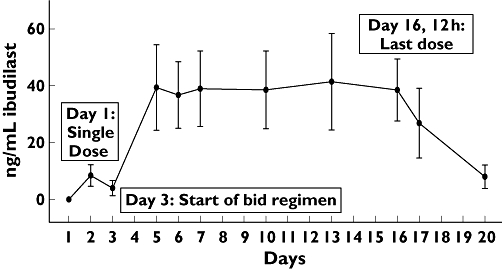

A plot of the mean trough concentrations of ibudilast (Figure 3) suggests that steady state was reached by day 5, 2 days after the start of the b.i.d. regimen. As indicated in Table 2, the geometric mean Cmax,ss concentration for ibudilast was approximately 60 ng ml−1 and Cmin,ss was approximately 20–30 ng ml−1. Correspondingly, at steady state, the peak (Cmax) was about two to three times higher than the trough (Cmin).

Figure 3.

Mean trough plasma concentrations of ibudilast. Trough ibudilast plasma concentrations from n = 14 subjects receiving a 30-mg single administration on day 1, followed by n = 10 subjects receiving 30 mg b.i.d. from day 3 to day 16. Data represents mean (± SD)

Table 2.

Plasma pharmacokinetic parameters for ibudilast

| Day 1(n = 14) | Day 6(n = 10) | Day 16(n = 10) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUCτ or AUCτss | ng h ml−1 | 246 (83.6) | 517 (157) | 507 (145) |

| AUC0–24 or AUC0–24,ss | ng h ml−1 | 373 (133) | 987 (302) | 1000 (303) |

| AUC0–∞ | ng h ml−1 | 610 (321) | NC | NC |

| Cmax or Cmax,ss | ng ml−1 | 32.0 (9.38) | 59.9 (19.6) | 59.9 (25.2) |

| Tmax or Tmax,ss* | h | 5.0 (3.0–8.0) | 3.53 (2.0–16.0) | 4.0 (1.0–22.0) |

| t1/2 | H | 19.2 (8.53) | NC | NC |

| Cmin,ss | ng ml−1 | NA | 27.5 (8.31) | 22.1 (10.0) |

| RA1 | [Cmax,ss/Cmax] | NA | 1.87 (0.38) | 1.87 (0.63) |

| RA2 | [AUCτss/AUCτ] | NA | 2.12 (0.36) | 2.08 (0.31) |

| RA3 | [AUCτ/AUC0–∞] | NA | 0.90 (0.26) | 0.88 (0.26) |

| RA1 day 16/day 6 | [Cmax,ss/Cmax] | NA | NA | 1.00 (0.19) |

| RA2 day 16/day 6 | [AUCτss/AUCτ] | NA | NA | 0.98 (0.09) |

For Tmax and Tmax,ss, the median (rather than the geometric mean) is reported and the values in parentheses are the ranges of observed values. Values reported are the geometric means (SD).

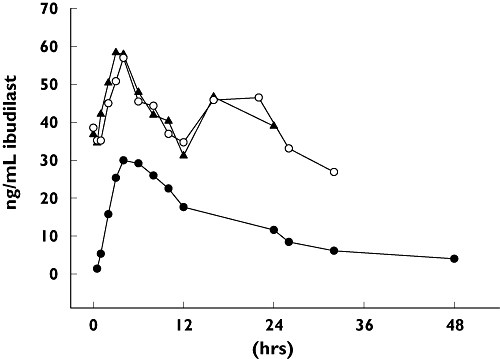

The geometric mean t1/2 was approximately 19 h. The median Tmax (4–6 h) was similar during the b.i.d. regimen (days 6 and 16) and after a single dose (day 1). As show in Figure 4, during the b.i.d. regimen Cmax appeared to be somewhat higher after the morning dose than after the evening dose. As further shown in Figure 4, the PK profile for ibudilast was shifted upward on days 6 and 16 relative to day 1; relative to the single dose (day 1), the b.i.d. regimen had a roughly twofold increase in plasma concentrations of ibudilast. This upward shift was reflected in the exposure parameters (AUC and Cmax). The geometric mean AUCτss during the bid regimen (516.6 ng h ml−1 for day 6 and 506.5 ng h ml−1 for day 16) was approximately double the AUCτ after a single dose (246.3 ng h ml−1); correspondingly, the accumulation ratio RA2 was about 2 (Table 2). The geometric mean Cmax was 87% higher during the b.i.d. regimen than after a single dose (accumulation ratio RA1 = 1.87 for both day 6 and day 16).

Figure 4.

Mean plasma concentrations of ibudilast on days 1, 6 and 16. Plasma concentration vs. time profile of ibudilast in n = 10 subjects receiving 30 mg b.i.d. from day 3 to day 16. Mean plasma levels on day 6 (▴) and day 16 (○) from the b.i.d. regimen are contrasted with n = 14 subjects receiving a single 30-mg dose on day 1 (•). All data are means

The geometric mean AUCτss during b.i.d. dosing (516.6 ng h ml−1 for day 6 and 506.5 ng h ml−1 for day 16) was about 10% smaller than the AUC0–∞ after a single dose, which corresponded to an RA3 of approximately 0.9. That the RA3 was <1.0 shows that there was no unexpected accumulation of ibudilast from the single dose to the multiple doses, and the multiple dose plasma concentrations were as predicted under linear PK.

The results for 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast largely confirmed the results for ibudilast, although these data were highly variable. The mean plasma 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast concentration–time profiles for men were slightly higher than those for women (data not shown), but at individual sample times the range of concentrations of the 6,7-dihydrodiol in men overlapped those of women, suggesting that sex differences (if any) were unimportant. Maximum plasma concentrations of 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast were achieved for most subjects within 10 h of administration of the first dose (day 1) and each of the doses during the multiple dose phase (days 6 and 16). The Cmax for the metabolite on day 1 ranged from 2.48 to 53.4 ng ml−1, from 4.95 to 91.6 ng ml−1 on day 6 and from 4.86 to 65.2 ng ml−1 on day 16. As shown in Table 3, these Cmax values tended to be about 20–50% of the Cmax for the parent drug. A comparable ratio of metabolite : parent was observed with the AUCs.

Table 3.

Metabolite/parent ratios of 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast

| Day 1(n = 12) | Day 6(n = 10) | Day 16(n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma AUCτ or AUCτss | 0.25 (0.64) | 0.22 (0.70) | 0.18 (0.35) |

| Plasma Cmax or Cmax,ss | 0.48 (0.63) | 0.26 (0.69) | 0.26 (0.56) |

| Urine 0–8 h | 1.00*,† (16.2) | 31.2* (23.6) | 37.8* (24.8) |

| Urine 8–16 h | 1.00*,† (22.2) | 43.8* (27.4) | 28.6* (23.2) |

Median value is reported.

n = 14. Values reported are the geometric means (SD).

Urine samples (which were collected from 0 to 8 h and from 8 to 16 h after the morning dose) had concentrations of 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast either equal to those of ibudilast (day 1; Table 3) or up to approximately 40 times greater than those of ibudilast (days 6 and 16). The fraction of the dose recovered in the urine as unchanged drug averaged ≤0.01% on day 1 (0–16 h), and the fraction recovered as 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast averaged ≤0.05%. Whereas ibudilast concentrations in the urine of most subjects were <3 ng ml−1 at all time points, the group mean urine concentrations of 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast were 5–8 ng ml−1 on day 1, 40–46 ng ml−1 on day 6 and 30–52 ng ml−1 on day 16.

Discussion

Ibudilast has been marketed in Japan and other Asian countries for >15 years for the treatment of bronchial asthma and, more recently, post-stroke dizziness. For the indications approved in Japan, patients typically are prescribed 10 mg orally twice daily (for asthma) or thrice daily (for cerebrovascular disorders), corresponding to respective doses of 20 and 30 mg day−1. In a population of about 15 000 patients treated with the drug in Japan, a relatively low incidence (3.39%) of adverse events was noted (Ketas® package insert; Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan). The most common adverse events reported were increased liver enzyme levels in 0.30–0.36% of patients, anorexia (0.58%) and nausea (0.56%). Rare cases of thrombocytopenia (reduced platelet counts) were also reported.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 238 subjects with post-stroke dizziness, for which the dose was 30 mg day−1 for 8 weeks, there were no significant differences in adverse drug reactions between the ibudilast and placebo groups [10]. Primary adverse effects in the ibudilast group were gastrointestinal distress (11.2%), including anorexia (4.3%), and hepatic dysfunction. In an open-label, 2-year study of ibudilast in 937 individuals examining the recurrence of stroke (dosed 30 mg day−1), adverse events, primarily gastrointestinal, were reported in 2.3% of subjects, and the drug was discontinued in 1.8% of subjects [11].

Based on our preclinical work [2], previous human PK data [6, 7], and preliminary assessments of exposure–response relationships in patients [8], we predict that pain relief in patients is likely to require doses greater than those approved and currently used for asthma and other conditions in Asia (i.e. >30 mg day−1). Clinical experience regarding larger doses of ibudilast is limited. However, two studies have reported using higher dose regimens in patients in multiweek trials with acceptable tolerability and no significant adverse events. Notably, in a study of 30 asthma patients, 13 were given 40 mg day−1 of ibudilast for 6 months, which was well tolerated [12]. The incidence of adverse events overall was <10%, and none was serious. Gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, abdominal discomfort) were mentioned as specific adverse events, but no further details were provided. In addition, ibudilast was given at 60 mg day−1 to 11 patients with multiple sclerosis for 4 weeks [13]. The drug was generally well tolerated, with no serious adverse events and adverse events limited to gastrointestinal distress. None appeared to be treatment-limiting. There was one case of early withdrawal by an elderly patient with heart palpitations, which resolved within 1 month of drug discontinuation.

The present study was a Phase I, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation in healthy subjects that assessed the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of ibudilast when administered as a single oral dose of 30 mg followed by multiple oral doses of 30 mg b.i.d. (60 mg day−1) for 14 days; 14 subjects were administered ibudilast and four were administered placebo.

The safety data indicate that ibudilast was generally well tolerated. The incidence of TEAEs was similar in both the ibudilast and placebo groups. The three most frequently reported TEAEs [hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating), headache and nausea] were experienced by subjects from both groups. The TEAEs of headache (four subjects) and nausea (three subjects, including two subjects with vomiting who withdrew from the study) were considered to be possibly or probably related to ibudilast. Nausea, which has been previously reported with ibudilast (Ketas® and Pinatos® Package Inserts) and other PDE inhibitors [14], was not unexpected. Interestingly, in the current study, headache and nausea were most frequently observed early in the multiday dosing period. Ibudilast appears to penetrate well into the CNS [LM Sanftner, JA Gibbons, MI Gross, BM Suzuki, FCA Gaeta, KW Johnson, unpublished data]; it is therefore possible that the TEAEs of headache and nausea are centrally triggered.

Nine subjects experienced TEAEs of hyperhidrosis that were considered to be possibly or probably related to study medication; however, the incidence was similar across both ibudilast and placebo groups, and therefore environmental factors could not be ruled out. There were no clear, consistent changes from baseline or individual shifts in laboratory parameters, and no consistent changes from baseline in vital signs or ECG were observed. There were no findings of thrombocytopenia or elevated liver enzymes, both of which are reported in the Pinatos® package insert as potential adverse events. Overall, ibudilast administered at 60 mg day−1 was well tolerated.

The PK data showed no apparent difference between men and women in ibudulast PK profiles. Given the small sample sizes used in this study, this is not considered definitive evidence that sex has no impact on ibudilast PK. Nevertheless, this result is in contrast to some findings in some animal species, in which profound sex differences were observed [LM Sanftner, JA Gibbons, MI Gross, BM Suzuki, FCA Gaeta, KW Johnson, unpublished data]. Another divergence from animal PK was observed in time dependency. Whereas rats may show increases in ibudilast clearance during multiple dose exposures to the drug [LM Sanftner, JA Gibbons, MI Gross, BM Suzuki, FCA Gaeta, KW Johnson, unpublished data], the current data from the Phase 1 study are consistent with time-invariant PK. For example, the median Tmax (4–6 h) was similar after multiple dosing (days 6 and 16) and after a single dose (day 1). Furthermore, the day 16/day 6 exposure ratios (RA1, Cmax,ss/Cmax and RA2, AUCτss/AUCτ) had geometric mean values of approximately 1, suggesting stationariness during the multiple-dose phase.

The data for 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast showed that plasma exposure to this metabolite was roughly 20–50% of the exposure to the parent drug. The urine data, which showed a higher ratio of the metabolite to the parent drug, provided evidence that biotransformation to 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast followed by urinary excretion of this metabolite is an important pathway for ibudilast elimination.

The PK results of the current study mostly corroborate the findings of two studies in the Japanese literature that describe oral ibudilast in Asian male subjects. These studies used 10-mg Ketas® capsules (Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co.), a delayed-release ibudilast product, of which Pinatos® is the generic equivalent. The first of these examined single-dose ibudilast at 10 mg [7] and the second examined multiple-dose ibudilast at 10 mg given three times daily for 8 days [6]. Both studies also found that the metabolite 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast circulated in plasma in concentrations that were roughly about half those of the parent molecule. In addition, approximately 50% of the circulating levels of 6,7-dihydrodiol-ibudilast were in the form of conjugated products, the nature of which was not identified (e.g. glucuronide, glutathione, etc.). Urine appeared to be the primary route (60%) of elimination. Little or no parent drug was seen in the urine and excretion of metabolites was primarily via the 6,7-dihydrodiol metabolite, approximately 85% of which was present in the urine as conjugated products. In the multiple-dose study, steady-state peak plasma levels of ibudilast and the 6,7 dihydrodiol metabolite and its conjugates were achieved within 3 days and appeared to be sustained for the next 5 days.

Although the PK findings of the present study mostly agree with the results of the previous studies [6, 7], there were differences in the t1/2, which was shorter in the Japanese studies than in the current study (roughly 8–12 h vs. 19 h). In addition, there were differences in the dose-normalized plasma exposure, which tended to be higher in the Japanese studies. In the present study, 30 mg of ibudilast resulted in a geometric mean Cmax of 32.0 (SD 9.38) ng ml−1 and a geometric mean AUC0–∞ of 609.8 (SD 321.2) ng h ml−1 (Table 2). When normalized per mg of dose, these parameters correspond to 1 ng ml−1 per mg (Cmax) and 20 ng h ml−1 per mg (AUC0–∞). In the Japanese studies, the corresponding dose-normalized parameters were nearly 3 ng ml−1 per mg (Cmax) and 40 ng h ml−1 per mg (AUC0–∞). Thus, whereas the terminal half-life tended to be shorter in the Japanese studies, exposure per mg of ibudilast administered was about two times higher. The difference in the terminal half-life may be related to differences in the sampling schedule, which was longer in the present study (48 h vs. 24–32 h). However, the reason for the exposure difference is unknown. It is possible that the racial composition of the cohorts may partially account for the exposure difference, the current trial comprising mostly Whites and the Japanese trials comprising entirely Asians. Although one of the two Asian subjects in the study had the highest exposure at steady state, considering the dataset as a whole, however, was inconclusive, as both of the Asian subjects had exposures close to the group mean.

In conclusion, the results of this study have indicated that ibudilast (AV411) was generally well tolerated in healthy adults when given as a single oral dose of 30 mg followed by 30 mg b.i.d. (60 mg day−1) for 14 days. Plasma PK reached steady state within 2 days of starting the twice-daily dosing regimen, and yielded exposures comparable to efficacy in animal models of neuropathic pain.

Competing interests

L.H., E.C., D.J., M.I.G., J.B.D., L.M.S. and K.W.J. are employed by, and possess stock options for, Avigen Inc., the developer of ibudilast (AV411). P.R. was Principal Investigator in the clinical trial and was not compensated as a consultant. J.A.G. was a paid consultant for Avigen Inc. The authors gratefully acknowledge the medicinal chemistry and development contributions of Dr Federico Gaeta, the support of Dr Ken Chahine, the clinical operation efforts of Satej Nadkarni, and assistance by Quintiles Australia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ledeboer A, Hutchinson MR, Watkins LR, Johnson KW. Ibudilast (AV-411). A new class therapeutic candidate for neuropathic pain and opioid withdrawal syndromes. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;16:935–50. doi: 10.1517/13543784.16.7.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ledeboer A, Liu T, Shumilla JA, Mahoney JH, Vijay S, Gross MI, Vargus JA, Sultzbaugh L, Claypool MD, Saftner LM, Watkins LR, Johnson KW. The glial modulatory drug AV411 attenuates mechanical allodynia in rat models of neuropathic pain. Neuron Glia Biol. 2007;2:279–91. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X0700035X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wieseler-Frank J, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Glial activation and pathological pain. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:389–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milligan ED, Langer SJ, Sloane EM, He L, Wieseler-Frank J, O’Connor K, Martin D, Forsayeth JR, Maier SF, Johnson K, Chavez RA, Leinwand LA, Watkins LR. Controlling pathological pain by adenovirally driven spinal production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-10. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2136–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutchinson MR, Bland ST, Johnson KW, Rice KC, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Opioid-induced glial activation: mechanisms of activation and implications for opioid analgesia, dependence, and reward. Scientific World Journal. 2007;7:98–111. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maeda S, Ishida R, Komuro M, Ohmuro S, Hashimoto H, Hotta M, Uchida H. Studies of KC-404 (3-Isobutyryl-2-isopopylpyrazolo-[1,5-apyridine]) pharmacokinetics in humans (Report 2) Clin Rep (Kiso to Rinsho) 1989;23:183–9. in Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uchida O, Ohmuro S, Hashimoto H, Irikura T. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of 3-isobutyryl-2-isopropylpyrazolo [1,5-a]pyridine (KC-404) in humans. Clin Rep (Kiso to Rinsho) 1985;19:42–50. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rolan PE. Methods for Targeting Glial Activation in the treatment of Neuropathic Pain. 10th International Conference on the Mechanisms and Treatment of Neuropathic Pain; Salt Lake City, Utah. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.FDA. Guidance for Industry. Bioanalytical Method Validation. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FaDA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinohara Y, Kusunoki T, Nakashima M. Clinical efficacy of ibudilast on vertigo and dizziness observed in patients with cerebral infarction in the chronic stage – a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a run-in period. Shinnkeitiryougaku (Neurol Ther) 2002;19:177–87. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohtomo H. Effect of ibudilast (Ketas) in preventing the recurrence of cerebral infarction. Yakuri to Rinsho (Jpn Pharmacol Ther) 1995;23:139–57. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawasaki A, Hoshino K, Osaki R, Mizushima Y, Yano S. Effect of ibudilast: a novel antiasthmatic agent, on airway hypersensitivity in bronchial asthma. J Asthma. 1992;29:245–52. doi: 10.3109/02770909209048938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng J, Misu T, Fujihara K, Sakoda S, Nakatsuji Y, Fukaura H, Kikuchi S, Tashiro K, Suzumura A, Ishii N, Sugamura K, Nakashima I, Itoyama Y. Ibudilast, a nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor, regulates Th1/Th2 balance and NKT cell subset in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004;10:494–8. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1070oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torphy TJ. PDE inhibitors – Second William Harvey Research Conference. Drugs with an expanding range of therapeutic uses. 1–3 December 1999, Nice, France. IDrugs. 2000;3:170–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]