SUMMARY

The role of natural killer (NK) cells in controlling hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and replication has not been fully delineated. We examined NK cell-mediated noncytolytic effect on full cycle HCV infection of human hepatocytes. Human hepatocytes (Huh7.5.1 cells) co-cultured with NK cells or treated with supernatants (SN) from NK cells cultures had significantly lower levels of HCV RNA and protein than control cells. This NK cell-mediated anti-HCV activity could be largely abolished by antibody to interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). The investigation of the mechanisms for NK cell-mediated anti-HCV activity showed that NK SN-treated hepatocytes expressed higher levels of IFN-α/β than the control cells. NK SN also enhanced IFN regulatory factor-3 and 7 expression in the hepatocytes. In addition, NK SN enhanced the expression of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 and 2, the nuclear factors that are essential for the activation of IFN-mediated antiviral pathways. These data provide direct evidence at cellular and molecular levels that NK cells have a key role in suppressing HCV infection of and replication in human hepatocytes.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, innate immunity, interferon, STAT

INTRODUCTION

A normal liver as the primary site of hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication contains high percentage of CD3-CD56+ natural killer (NK) cells [1]. NK cells are a central component of the innate immune system and provide a critical first line of defence mechanism against viral infections through their rapid cytotoxic activity and production of antiviral cytokines, such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) [2]. NK cells eliminate virus-infected hepatocytes through direct lysis (perforin/granzyme) or indirect (secretion of antiviral cytokines) mechanisms. In addition, NK cells play an essential role in recruiting virus-specific T cells and exerting antiviral immunity in the liver [3]. However, HCV has developed multiple strategies to evade the host’s NK cell response, which is evidenced by the observations that patients with chronic HCV infection exhibit diminished NK cell numbers in the liver [4-6] and decreased NK cell activity in the peripheral blood compared with uninfected controls [7,8]. Patients who clear HCV infection after IFN-α therapy (responders) exhibit a significant increase in NK cell numbers and activity in the peripheral blood compared with nonresponders [7,9,10]. A number of investigations have examined NK cell function on exposure to HCV components with intriguing data. Tseng and Klimpel [11] and Crotta et al. [12] reported that NK cell function was impaired by HCV envelope protein E2 in vitro. However, studies of ex vivo NK cell function in patients with chronic HCV resulted in mixed results [5,7,8,13-15]. A recent study reported that NK cell cytolytic function does not appear to be impaired in chronic HCV infection [16]. Thus, more intensive studies are needed to examine HCV-NK cell interactions.

The interactions between HCV and the innate immune system play a critical role in the immunopathogenesis of HCV disease. While most research efforts have focused on the role of the interactions between adaptive immunity and the viral factors in the immunopathogenesis of HCV disease, limited information is available about the role of NK cell-mediated innate immunity in controlling HCV infection of hepatocytes. There is a lack of direct evidence at cellular and molecular levels that NK cells have the ability to suppress full cycle replication of HCV in human hepatocytes. We previously demonstrated that NK cells suppressed HCV replicon expression in human hepatocytes [17]. However, the HCV replicons do not permit analysis of the complete life cycle of HCV. Thus, our understanding about the direct interactions between NK cells and HCV is still limited. Fortunately, the recent establishment of a full-length genotype 2a HCV genome (JFH1) that replicates and produces infectious virus in human hepatocytes [18-21] has provided a clinical relevant model for studying the interactions between host immune cells and HCV infection. Therefore, in the present study we examined the anti-HCV activity of NK cells in this new cell system that supports full cycle viral replication. In addition, we used this model to investigate the molecular mechanisms involved in NK cell-mediated anti-HCV action in human hepatocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Recombinant IFN-γ and the monoclonal antibody (Ab) against IFN-γ were obtained from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Goat anti-IFN-α/β receptor 1 (anti-IFN-α/β R1) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit IgG Ab and HRP-conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG Ab were purchased from Jackson Immune Research Labs (West Grove, PA, USA). The Ab to HCV NS5A protein was obtained from Chiron Company (Emeryville, CA, USA). Antibodies to signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (STAT1), STAT2, IFN regulatory factor-3 (IRF-3), and IRF-7 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Cells and cell lines

Primary NK (PNK) cells were isolated from peripheral blood of five adult healthy donors. NK cells were enriched by immunomagnetic negative selection (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). The purity (% of CD56+ CD3-) of isolated NK cells measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was >95%. Enriched PNK cells were maintained in 24-well plates at a density of 106 cells/well in 1 mL 10% Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) media, supplemented with 100 U/mL human rIL-2 (Hoffmann-La Roche, Nutley, NJ, USA). The human NK cell line (NK-92) was derived from an individual with lymphoma [22] and was cultured in 10% RPMI supplemented with 100 U/mL human rIL-2 for continued in vitro growth. NK-92 cell culture supernatants (NK92 SN) were collected every 48 h during cell passages, while PNK cell culture SN (PNK SN) were collected after 72 h in vitro culture. The collected NK SNs were then filtered through 0.22-μm-pore-size filters and stored at -70 °C until use. The PNK SN used in this study was a pooled SN from PNK cells isolated from five different healthy donors. Huh7.5.1 cells were kindly gifted from Dr Charles Rice (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY, USA). Huh7.5.1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM Hepes, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin and 2 mm l-glutamine at 5% CO2. The cell viability was measured by cell proliferation assay. In all cases, the limulus amebocyte lysate assay demonstrated that the media and reagents are endotoxin-free.

Co-culture of human hepatocytes with NK cells and NK SN treatment

For the co-culture experiments, human hepatic cells (HCV JFH1-infected Huh7.5.1) were co-cultured with NK (PNK and NK-92) cells at specified effector-to-target cell ratios in 0.4-μm-pore-transwell tissue culture plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA). Huh7.5.1 cells (5 × 104 cells) in the lower compartment were co-cultured with different number of NK cells placed in the upper compartment. The hepatic cells in the lower compartments were collected for RNA extraction and HCV RNA was assessed by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) at different time points after the co-culture. For the experiments using NK SN, Huh7.5.1 cells plated in triplicate (5 × 104/well) in 24-well culture plate were cultured in media conditioned with or without NK SN (25%, v/v) for either 24 h prior to HCV infection, or simultaneously or 8 h postinfection. The cells were then washed five times with plain DMEM to remove input virus after 6 h incubation with HCV JFH1 and then cultured in the presence or absence of NK SN for different time points.

HCV infection of human hepatocytes

To generate infectious HCV JFH1, in vitro transcribed genomic JFH1 RNA was transfected into Huh7.5.1 cells as previously described [19]. Cell culture SN collected at day 10 posttransfection were centrifuged and passed through 0.22-μm filter. The cell-free media was used as virus stocks. Stocks were aliquoted and stored at -80 °C. Infection of Huh7.5.1 cells with HCV JFH1 was carried out as previously described [19].

RNA quantification

Total RNA (1 μg) extracted from Huh7.5.1 cells was subjected to reverse transcription using the reverse transcription system from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). The real-time RT-PCR for the HCV, IFN-α, IFN-β, IRF-3 and IRF-7 RNA quantification was performed as previously described [17,23]. The amplified products were analyzed using the software MyiQ provided with the thermocycler (Icycler iQ real-time PCR detection system, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA were used as an endogenous reference to normalize the quantities of target mRNA. To determine the amount of HCV RNA in culture SN, HCV RNA was extracted from 200 μL of culture medium by TRI-Reagent-BD (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). Extracted RNA was purified by using an RNeasy minikit and treated with RNase-free DNase digestion (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Copy numbers of HCV RNA were determined by real-time RT-PCR as described previously [17,23]. The special oligonucleotide primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. The primers were synthesized by Intergrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA, USA).

Table 1.

Primer pairs for real-time RT-PCR

| Primer | Orientation | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Sense | 5′-GGTGGTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACA-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-GTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCGTTGT-3′ | |

| HCV | Sense | 5′-RAYCACTCCCCTGTGAGGACC-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-TGRTGCACGGTCTACGAGACCTC-3′ | |

| IFN-α | Sense | 5′-TTTCTCCTGCCTGAAGGACAG-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-GCTCATGATTTCTGCTCTGACA-3′ | |

| IFN-β | Sense | 5′-AAAGAAGCAGCAATTTTCAGC-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-CCTTGGCCTTCAGGTAATGCA-3′ | |

| IRF-3 | Sense | 5′-ACCAGCCGTGGACCAAGAG-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-TACCAAGGCCCTGAGGCAC-3′ | |

| IRF-7 | Sense | 5′-TGGTCCTGGTGAAGCTGGAA-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-GATGTCGTCATAGAGGCTGTTGG-3′ |

ELISA assay

ELISA kits for IFN-α and IFN-γ were purchased from PBL Biomedical Laboratories (Piscataway, NJ, USA). The assay was performed according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Western blot

Western blot assay was performed as described [24]. At the time of harvest, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and total cellular proteins were extracted with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (0.5% Non-idet P40, 10 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% sodium dodecyl sulphate). Protein concentrations were determined by the DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl/polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with NuPAGE Novex precast with 4-12% Bis-Tris gradient gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The primary antibodies used for Western blot were as follows: rabbit anti-STAT1 (1:1000), mouse anti-STAT2 (1:200), rabbit anti-actin (1:2000), rabbit anti-IRF-3 (1:500), rabbit anti-IRF-7 (1:200) and rabbit anti-NS5A (1:2500). The secondary antibodies were HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG Ab (1:10 000) or goat anti-mouse IgG Ab (1:5000). The bound antibodies were visualized by developing the membrane in SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Statistical analysis

Where appropriate, data were expressed as mean ± SD of triplicate cultures. For comparison of the mean of two groups, statistical significance was assessed by Student’s t-test. If there were more than two groups, one-way repeated measures of ANOVA was used. Statistical analyses were performed with Graphpad Instat Statistical Software (Graphpad™, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

NK cells suppress HCV replication

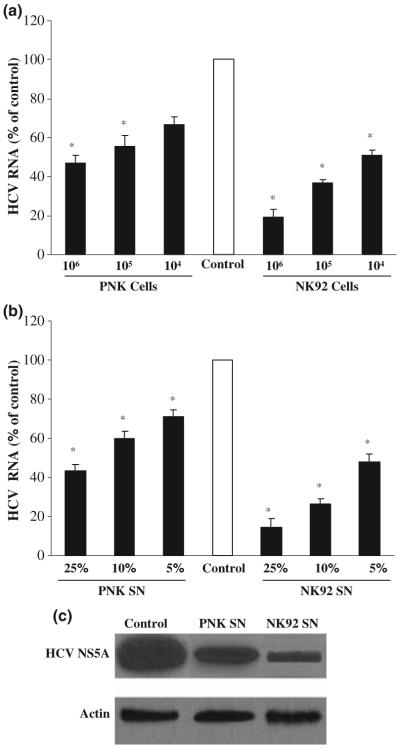

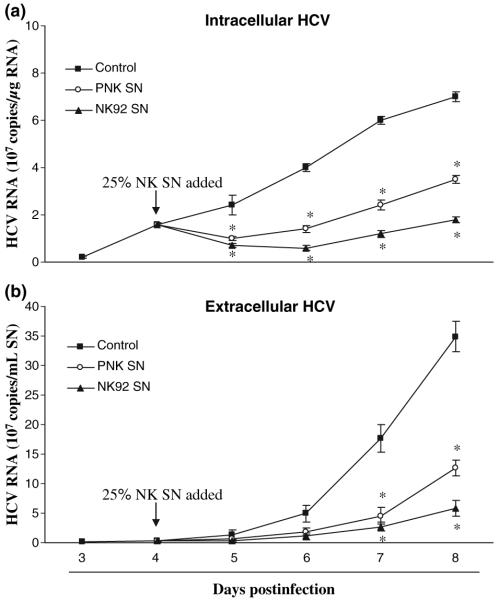

We hypothesized that NK cells release anti-HCV soluble factor(s) that suppress infectious HCV infection of human hepatocytes. Two approaches were carried out to test this hypothesis. In the first set of experiments, a transwell co-culture system was used to determine whether NK cells release soluble factor(s) that suppress HCV infection of human hepatocytes. NK cells in the top compartment (insert) were co-cultured with JFH1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells that were plated in the bottom compartment. HCV RNA expression was markedly inhibited (up to 80-90% of suppression) in the hepatocytes co-cultured with NK cells (Fig. 1a). The degree of inhibition was positively correlated with the number of NK cells added to the co-culture system (Fig. 1a). In the second set of experiments, we examined whether NK SN collected from NK (PNK or NK92) cell cultures have the anti-HCV activity. NK SN inhibited HCV RNA expression in a concentration-dependent fashion (Fig. 1b). The anti-HCV activity of NK SN in HCV JFH1-infected hepatocytes was also demonstrated by Western blot assay, showing that NK SN inhibited HCV NS5A protein expression (Fig. 1c). NK SN, when added to HCV JFH1-infected hepatocytes once, could suppress intercellular viral replication for at least 96 h (Fig. 2a), which was confirmed by the observation that NK SN-treated hepatocytes released significant lower levels of HCV RNA than untreated control cells (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 1.

NK cells release soluble factor(s) to suppress expression of HCV RNA and NS5A protein in human hepatocytes. (a) Co-culture of NK cells with HCV JFH1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells. At day 4 postinfection, Huh7.5.1 cells in the low compartment of a 24-well transwell co-culture system were co-cultured with primary NK (PNK) or NK92 cells that were added to the top compartment of the co-culture system. (b) Effect of NK SN on HCV JFH1 RNA expression. JFH1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells (day 4 postinfection) were cultured in media conditioned with or without NK SN (PNK or NK92) for 48 h. Total cellular RNA extracted from the hepatic cells was subjected to real-time RT-PCR for HCV and GAPDH RNA quantification. The data are expressed as HCV RNA levels relative to the control (% of control, no NK cells on the top compartment or without treatment with NK SN, which is defined as 100%). The results shown are mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three separate experiments (*, P < 0.05, NK cells or NK SN vs control). (c) Effect of NK SN on NS5A protein expression. NK SN (PNK or NK92) was added to HCV JFH1-infected hepatocyte cultures at day 4 postinfection. Total proteins were extracted from the cells 48 h posttreatment and subjected to Western blot assay using antibodies specific to NS5A and actin. One representative of three experiments is shown.

Fig. 2.

Time course of inhibition of HCV RNA expression by NK SN. Primary NK (PNK) SN or NK-92 SN was added to HCV JFH1-infected hepatocyte cultures at day 4 postinfection. Intracellular (a) or extracellular (b) RNA was extracted from hepatocytes or culture supernatants (SN) at indicated time points and subjected to the real-time RT-PCR for HCV and GAPDH RNA quantification. Intracellular (a) and extracellular (b) HCV RNA expression is expressed as either HCV RNA 107 copies/μg cellular RNA or 107 copies/mL SN, respectively. The results shown are mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three experiments (*, P < 0.05, NK SN-treated vs untreated).

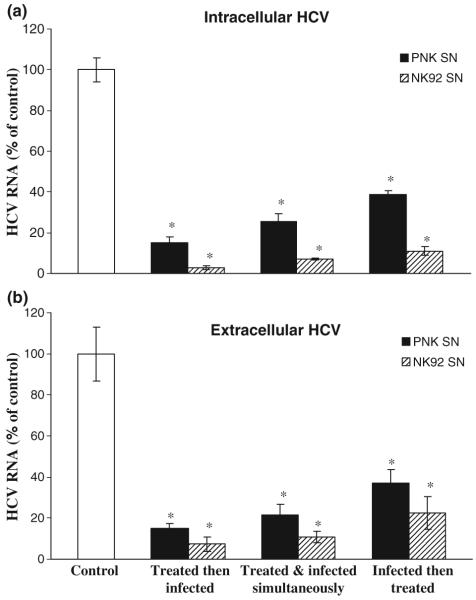

Knowing that NK cells have the ability to release anti-HCV soluble factor(s), we further examined the anti-HCV activity of NK cells under three different conditions: Huh7.5.1 cells were incubated with NK SN either 24 h before HCV JFH1 infection, or simultaneously with HCV JFH1, or 8 h after HCV JFH1 infection. Cells that were pretreated for 24 h with 25% (v/v) of NK SN and then infected had significantly lower levels of HCV RNA than untreated and infected cells (Fig. 3a). Similarly, cells treated with NK SN and infected simultaneously showed decreased expression of HCV RNA than the control cells (Fig. 3a). NK SN, when added to the cell culture 8 h after HCV JFH1 infection, also suppressed HCV RNA expression in the infected cells (Fig. 3a). Under three different conditions, all the NK SN-treated hepatocytes released significant lower levels of HCV RNA than untreated control cells (Fig. 3b). In addition, although both PNK SN and NK92 SN were shown to inhibit HCV RNA expression, NK92 SN had a greater anti-HCV effect than PNK SN (Figs 2 & 3).

Fig. 3.

Suppression of HCV RNA expression by NK SN under different conditions. Huh7.5.1 cells were cultured in media conditioned with or without primary NK (PNK) SN or NK92 SN for either 24 h prior to HCV infection, or simultaneously or 8 h postinfection. The cells were then washed five times to remove input HCV after 6 h incubation with HCV JFH1 and then cultured in the presence or absence of NK SN for 8 days. Intracellular (a) and extracellular (b) RNA extracted from hepatocytes or culture supernatants (SN) at day 8 postinfection was subjected to the real-time RT-PCR for HCV and GAPDH RNA quantification. Intracellular (a) and extracellular (b) HCV RNA expression is expressed as HCV RNA levels relative (%) to the control (untreated cell cultures, which are defined as 100%). The results shown are mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three experiments (*, P < 0.05, NK SN-treated vs untreated).

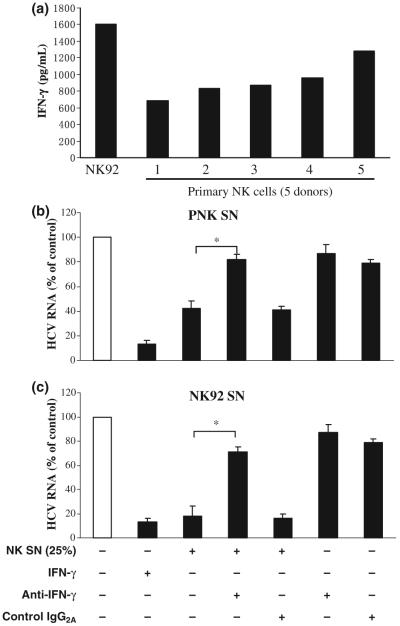

IFN-γ is a primary player in the NK cell-mediated anti-HCV activity

Since NK cells play a significant role in innate antiviral defence, partly through their ability to secrete cytokines such as IFN-γ [25], we examined whether IFN-γ is responsible for NK cell-mediated anti-HCV activity. NK92 cells and PNK cells isolated from healthy donors produced IFN-γ (Fig. 4a). NK92 cells produced higher levels of IFN-γ than PNK cells (Fig. 4a). Thus, we further determined whether IFN-γ has the ability to inhibit full cycle HCV expression in human hepatocytes. We showed that when recombinant IFN-γ was added to HCV JFH1-infected hepatocyte cultures, HCV RNA expression was inhibited (Fig. 4b,c). We then studied whether the Ab to IFN-γ is capable of abolishing NK cell-mediated anti-HCV activity. It was demonstrated that the preincubation of NK SN with anti-IFN-γ Ab largely neutralized the anti-HCV activity of NK SN (Fig. 4b,c).

Fig. 4.

IFN-γ is involved in NK SN-mediated anti-HCV activity. (a) IFN-γ production by primary NK (PNK) cells and NK92 cells. IFN-γ levels in media from PNK cells (five donors) and NK-92 cells were determined by ELISA. (b) HCV JFH1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells were cultured in the presence or absence of NK SN and/or antibody (Ab) against IFN-γ. For the cultures using both NK SN and Ab to IFN-γ, the NK SN was preincubated with the Ab to IFN-γ for 30 min before being added to JFH1-infected hepatocyte cultures at day 4 postinfection. IFN-γ (1000 U/mL) alone was added to the cell cultures as a positive control to determine the neutralization ability of the Ab to IFN-γ. Mouse IgG2A was used to determine the specificity of the Ab to IFN-γ. Total cellular RNA extracted from hepatocytes was subjected to the real-time RT-PCR for HCV and GAPDH RNA quantification at 48 h postexposure to NK SN. The data are expressed as HCV RNA levels relative (% of control, no Abs treatment and no NK SN added, which is defined as 100%). The results shown are mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three experiments (*, P < 0.05, IFN-γ Ab plus NK SN vs NK SN only). +, in the presence; -, in the absence.

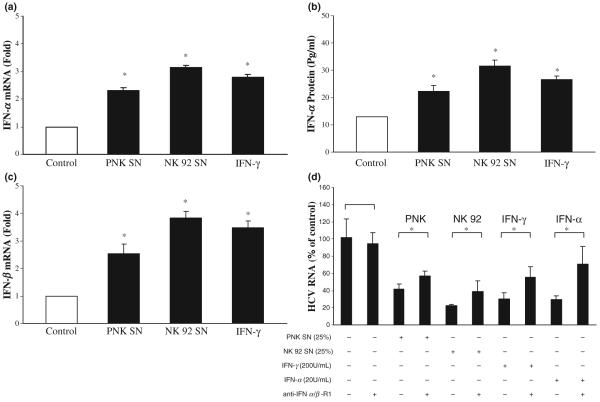

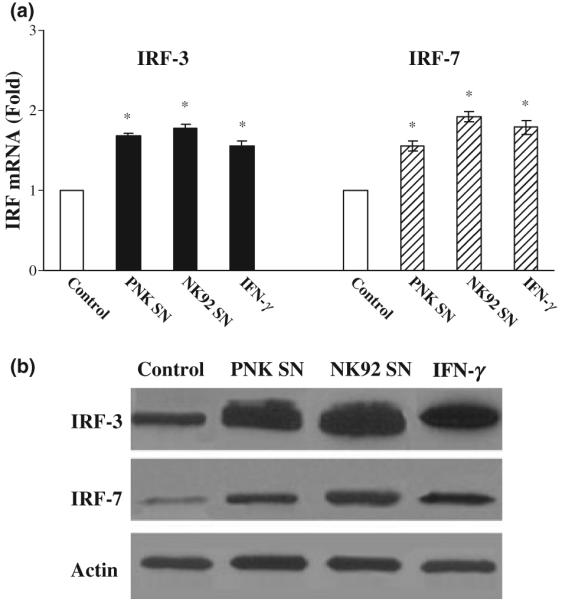

NK SN induces the expression of intracellular IFN-α/β and IRFs

Since intracellular IFN-α produced by the hepatic cells has a central role in inhibiting HCV replication [26], we examined whether NK SN has the ability to induce intracellular IFN-α expression in the hepatic cells. In line with our previous study [17], we showed that Huh7.5.1 treated with NK SN expressed higher levels of endogenous IFN-α than untreated control cells at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 5a,b). In addition, Huh7.5.1 cells treated with NK SN expressed higher levels of endogenous IFN-β mRNA than untreated control cells (Fig. 5c). When HCV JFH1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells were preincubated with Ab to IFN-α/β R1 and then subjected to NK SN treatment, the levels of HCV RNA were significantly increased compared with those from NK SN-treated cells without preincubation with anti-IFN-α/β R1 (Fig. 5d). To investigate whether the induction of intracellular IFN-α/β by NK SN is a result of the activation of IRF-3 and IRF-7, the major modulators of type I IFNs in JAK/STAT pathway, we analyzed the expression of IRF-3 and IRF-7 in HCV JFH1-infected hepatocytes. Cells treated with NK SN showed increased expression of IRF-3 and IRF-7 at both mRNA (Fig. 6a) and protein (Fig. 6b) levels.

Fig. 5.

Effect of NK SN on the expression of IFN-α/β in human hepatocytes. (a and c) IFN-α/β RNA expression. At day 4 postinfection, primary NK (PNK) SN or NK-92 SN was added to HCV JFH1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells (25%, v/v). Total cellular RNA was extracted from the cell cultures at 12 h posttreatment with NK SN and then subjected to real-time RT-PCR for IFN-α/β and GAPDH RNA quantification. The data were expressed as IFN-α/β RNA levels relative (fold) to the control (without NK SN, which is defined as 1). The results shown are mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three separate experiments. (b) IFN-α protein expression. HCV JFH1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells (day 4 postinfection) were cultured in the presence or absence NK (PNK and NK-92) SN (25%, v/v) for 48 h. SNs from the cell cultures were then harvested for IFN-α protein ELISA assay. The results shown are mean ± SD of triplicate cultures (*, P < 0.05, NK SN-treated vs untreated). (d) Antibody (Ab) to IFN-α/β R1 blocks NK SN-mediated anti-HCV activity. HCV JFH1-infectd Huh7.5.1 cells were incubated with or without goat anti-IFN-α/β R1 (10 μg/mL) for 1 h prior to the addition of the NK SN. IFN-γ (200 U/mL) or IFN-α (20 U/mL) treatment of human hepatocytes was used as the controls. HCV RNA levels in Huh7.5.1 cells were determined at 48 h postexposure to NK SN. Total cellular RNA extracted from Huh7.5.1 cells was subjected to the real-time RT-PCR for HCV and GAPDH RNA quantification. The data are expressed as HCV RNA levels relative (%) to control (no Ab treatment and no NKT SN added, which is defined as 100%). The results shown are mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three separate experiments (*, P < 0.05, anti-IFN-α/β R1 plus NK SN vs NK SN only). +, in the presence; -, in the absence.

Fig. 6.

NK SN induces the expression of IRF-3 and IRF-7 in human hepatocytes. (a) IRF-3 and IRF-7 mRNA expression. Huh7.5.1 cells (day 4 postinfection) were cultured in the presence or absence 25% of primary NK (PNK) SN or NK-92 SN for 12 h. Total cellular RNA extracted from the cell cultures was subjected to real-time RT-PCR for IRF-3, IRF-7 and GAPDH RNA quantification. The data are expressed as IRF RNA levels relative (fold) to the control (without NK SN, which is defined as 1). The results shown are mean ± SD of triplicate cultures, representative of three experiments (*, P < 0.05, NK SN-treated vs untreated). (b) IRF-3 and IRF-7 protein expression. Huh7.5.1 cells (day 4 postinfection) were cultured in the presence or absence 25% of NK SN (PNK and NK-92) for 48 h, total proteins extracted from the cells were subjected to Western blot. One representative of three experiments is shown.

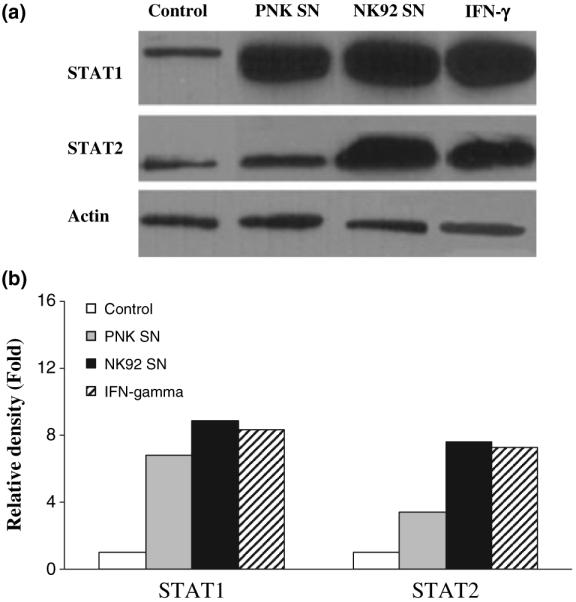

NK SN enhances expression of STAT1 and STAT2

While STAT1 plays a key role in signalling for type I IFN expression, STAT2 also has a well-established role as an essential mediator of signal transduction through the type I IFN receptors [27,28]. We hypothesized that NK SN that contains IFN-γ activates both STAT1 and STAT2 expression in the hepatic cells. As expected, NK SN-treated hepatic cells had higher levels of STAT1 and STAT2 proteins than untreated control cells (Fig. 7). The role of IFN-γ in NK SN-mediated induction of STAT1 and STAT2 was supported by the observation that the addition of recombinant IFN-γ to the same cell cultures resulted in the similar effects as NK SN (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Effect of NK SN on STAT1 and STAT2 protein expression. (a) HCV JFH1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells at day 4 postinfection were cultured in media conditioned with 25% of primary NK (PNK) SN or NK-92 SN for 48 h. Total proteins extracted from HCV JFH1-infected Huh7.5.1 cells were subjected to Western blot assay using antibodies (Abs) specific to STAT1, STAT2 and actin. IFN-γ (1000 U/mL) was used as a positive control. One representative experiment is shown. (b) The data presented in Fig. 7a was analyzed by relative density which was normalized to actin (untreated HCV JFH1-infected cells which was defined as 1).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we further examined the noncytolytic anti-HCV activity of NK cells in the newly developed infectious HCV (JFH1) system. We have demonstrated that NK cells release soluble factors that potently inhibit HCV replication in human hepatocytes. This NK cell-mediated anti-HCV activity is potent, which is evidenced by the observations that as much as 90% of HCV RNA expression was suppressed in the hepatocytes either co-cultured with NK cells or exposed to NK SN. This NK cell-mediated anti-HCV activity is also innate, since the PNK cells used in the experiments were isolated from HCV seronegative subjects. We subsequently identified that IFN-γ is a major player in NK cell-mediated anti-HCV activity. The critical role of IFN-γ in NK SN-mediated anti-HCV action was demonstrated by the experiments showing that the preincubation NK SN with Ab to IFN-γ largely blocked NK SN-mediated anti-HCV activity in hepatocytes (Fig. 4b,c). The anti-HCV role of IFN-γ produced by NK cells were further confirmed by the observation that SN from NK92 cells produced higher levels of IFN-γ than PNK cells (Fig. 4a), which corresponds to the finding that the anti-HCV activity of NK92 SN superior to that of PNK SN (Figs 1-3). IFN-γ is produced by cells of immune system in response to pathogens. NK cells are one of primary immune cells that produce IFN-γ that has a significant role in the control of viral infections. It has been shown that IFN-γ is a powerful inhibitor of HCV replication [25,29]. We previously demonstrated that NK cells, through an IFN-γ-dependent mechanism, inhibited HCV replicon expression in the hepatocytes [17]. However, HCV replicon cells do not produce infectious HCV, and the in vivo implication of this previous finding remains to be determined. Thus, the current study using the newly established HCV infectious cell system [18-21] serves not only as a confirmatory investigation but also provides new and significant information that may have clinical relevance. For example, in contrast to HCV replicon system where we were only able to examine the impact of NK cells on intracellular HCV replicon expression, the infectious HCV cell model allows us to determine whether NK cells have the ability to inhibit HCV infection of the naïve hepatocytes. We demonstrated that hepatocytes pretreated with NK SN were less susceptible to HCV JFH1 infection than untreated cells (Fig. 3a). In addition, we were able to show that NK SN-treated hepatocytes released significant lower levels of HCV that untreated control cells (Fig. 3b).

While it has been extensively demonstrated that IFN has the antiviral property, the mechanism of IFN-mediated antiviral activity remains obscure. We hypothesized that IFN-γ in NK SN activates intracellular innate immunity in hepatocytes. One of the critical components in the intrahepatic innate immunity against HCV infection is IFN-α [26]. Clinically, IFN-α has been used as a major treatment for chronic HCV infection. In addition, IFN-β plays a critical role in the host innate immunity against viral infections. Given the vital role of intracellular IFN-α/β in determining whether HCV can establish persistent infection, it is of importance to determine whether IFN-γ or NK SN induces the expression of endogenous IFN-α/β in HCV-infected hepatocytes, which inhibits HCV replication. Our finding that NK SN induces intracellular IFN-α/β expression in human hepatocytes (Fig. 5) provides a sound mechanism for NK SN-mediated anti-HCV activity. Similarly, recombinant IFN-γ, when added to HCV JFH1-infected hepatocyte cultures, induced endogenous IFN-α/β expression, suggesting that it is likely that IFN-γ in NK SN is primarily responsible for NK-SN-mediated induction of endogenous IFN-α/β in human hepatocytes.. The contribution of IFN-γ to NK cell-mediated noncytolytic anti-HCV activity is also supported by the observation that NK SN enhanced the expression of STAT1 and STAT2, the nuclear factors that are essential for the activation of type I IFN-mediated antiviral pathways. It is well known that IFN-γ signalling activates both STAT1 and STAT2 [27,28], and functional STAT1 and STAT2 are crucial to host innate responses to viral infections. The IFN-γ and IFN-α/β signal pathways interact at multiple levels. Takaoka et al. demonstrated that IFN-γ signalling in mouse embryonic fibroblasts requires a constitutive subthreshold IFN-α/β signal, while low levels of IFN-α/β signal are necessary for maintaining its receptor in the phosphorylated form, thus providing a functional aid for efficient assembly of IFN-γ-activated STAT1 homodimers [30].

Our current studies showed that NK SN or IFN-γ induced the expression of IRF-3 and IRF-7 in human hepatocytes. Both IRF-3 and IRF-7 play distinct and essential roles in the type I IFN-mediated antiviral response [31,32], as signalling though IRF-3 and IRF-7 stimulates IFN-α/β production [33]. A well-characterized collaboration exists between IRF-3 and IRF-7, which serves to amplify the antiviral response. Specifically, during viral infection, IRF-3 has an early role in inducing transcription of IFN-α and IFN-β that can induce IRF-7 expression. The newly synthesized IRF-7 then promotes transcription of different IFN subunits, thereby creating a positive feedback loop [34]. As with IRF-3, virus infection appears to induce phosphorylation of IRF-7 at its C-terminus, a region that is highly homologous to IRF-3 C-terminal end. IRF-7 forms homodimers or heterodimers with IRF-3, both of which have transactivating potential. IRF-7 not only induces IFN-α, but also activates many IFN-stimulated genes that have antiviral activities. In addition, IRF-7 may directly inhibit HCV replication. It has been demonstrated that several proteins of HCV have the ability to suppress the expression of IRF-3 and IRF-7, which inhibit the production of endogenous IFN-α in human hepatocytes. Foy et al. showed that HCV NS3/4A serine protease blocks the phosphorylation and effector action of IRF-3 [35]. We have previously demonstrated that HCV NS5A protein inhibits the expression of IRF-7 [26]. Thus, the findings demonstrating the induction of both IRF-3 and IRF-7 expression by NK SN has provided a reasonable mechanism for NK SN-mediated enhancement of endogenous type I IFN expression in hepatocytes.

Collectively, the present study using the clinical relevant cell model that produces infectious HCV has provided not only confirmatory but also new information, demonstrating that NK cells have an important role in the host innate defence against HCV infection and replication in hepatocytes. More importantly, we showed that IFN-γ produced by NK cells, through the activation of intracellular type I IFN system, inhibits HCV replication in hepatocytes. This finding is particularly important given the fact that NK cells are abundant in liver and are also a critical component of host innate immune defence mechanism. Although our in vitro studies using both PNK cells and NK cell line have provided insights into the noncytolytic anti-HCV ability of NK cells in human hepatocytes, further studies are needed in order to validate the clinical significance of our findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs Charles Rice (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY, USA) and Takija Wakita (Tokyo Metropolitan Institute for Neuroscience, Tokyo, Japan) for generously providing us with the Huh7.5.1 cell line and the plasmid pJFH1, respectively. This study was supported by the grants from the National Institutes of Health (DA 12815 and DA 22177).

Abbreviations

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- IFN-γ

interferon gamma

- IRF-3

IFN regulatory factor-3

- NK

natural killer

- PNK

primary NK

- SN

supernatants

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- STAT1

signal transducer and activator of transcription-1

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors do not have a commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nuti S, Rosa D, Valiante NM, et al. Dynamics of intra-hepatic lymphocytes in chronic hepatitis C: enrichment for Valpha24+ T cells and rapid elimination of effector cells by apoptosis. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28(11):3448–3455. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199811)28:11<3448::AID-IMMU3448>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biron CA. Activation and function of natural killer cell responses during viral infections. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9(1):24–34. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang KM. Immunopathogenesis of hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7(1):89–105. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(02)00068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiore G, Angarano I, Caccetta L, et al. In-situ immunophenotyping study of hepatic-infiltrating cytotoxic cells in chronic active hepatitis C. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9(5):491–496. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199705000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawarabayashi N, Seki S, Hatsuse K, et al. Decrease of CD56(+)T cells and natural killer cells in cirrhotic livers with hepatitis C may be involved in their susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2000;32(5):962–969. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.19362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yonekura K, Ichida T, Sato K, et al. Liver-infiltrating CD56 positive T lymphocytes in hepatitis C virus infection. Liver. 2000;20(5):357–365. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020005357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonavita MS, Franco A, Paroli M, et al. Normalization of depressed natural killer activity after interferon-alpha therapy is associated with a low frequency of relapse in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Int J Tissue React. 1993;15(1):11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corado J, Toro F, Rivera H, Bianco NE, Deibis L, De Sanctis JB. Impairment of natural killer (NK) cytotoxic activity in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;109(3):451–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4581355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Page C, Genin P, Baines MG, Hiscott J. Interferon activation and innate immunity. Rev Immunogenet. 2000;2(3):374–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Appasamy R, Bryant J, Hassanein T, Van Thiel DH, Whiteside TL. Effects of therapy with interferon-alpha on peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets and NK activity in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;73(3):350–357. doi: 10.1006/clin.1994.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tseng CT, Klimpel GR. Binding of the hepatitis C virus envelope protein E2 to CD81 inhibits natural killer cell functions. J Exp Med. 2002;195(1):43–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crotta S, Stilla A, Wack A, et al. Inhibition of natural killer cells through engagement of CD81 by the major hepatitis C virus envelope protein. J Exp Med. 2002;195(1):35–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duesberg U, Schneiders AM, Flieger D, Inchauspe G, Sauerbruch T, Spengler U. Natural cytotoxicity and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) is not impaired in patients suffering from chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2001;35(5):650–657. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortaldo JR, Oldham RK, Cannon GC, Herberman RB. Specificity of natural cytotoxic reactivity of normal human lymphocytes against a myeloid leukemia cell line. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977;59(1):77–82. doi: 10.1093/jnci/59.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Par G, Rukavina D, Podack ER, et al. Decrease in CD3-negative-CD8dim(+) and Vdelta2/Vgamma9 TcR+ peripheral blood lymphocyte counts, low perforin expression and the impairment of natural killer cell activity is associated with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2002;37(4):514–522. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morishima C, Paschal DM, Wang CC, et al. Decreased NK cell frequency in chronic hepatitis C does not affect ex vivo cytolytic killing. Hepatology. 2006;43(3):573–580. doi: 10.1002/hep.21073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Zhang T, Ho C, Orange JS, Douglas SD, Ho WZ. Natural killer cells inhibit hepatitis C virus expression. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76(6):1171–1179. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0604372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, et al. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science. 2005;309(5734):623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1114016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat Med. 2005;11(7):791–796. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong J, Gastaminza P, Cheng G, et al. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(26):9294–9299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503596102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tscherne DM, Jones CT, Evans MJ, Lindenbach BD, McKeating JA, Rice CM. Time- and temperature-dependent activation of hepatitis C virus for low-pH-triggered entry. J Virol. 2006;80(4):1734–1741. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1734-1741.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gong JH, Maki G, Klingemann HG. Characterization of a human cell line (NK-92) with phenotypical and functional characteristics of activated natural killer cells. Leukemia. 1994;8(4):652–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang JH, Lai JP, Douglas SD, Metzger D, Zhu XH, Ho WZ. Real-time RT-PCR for quantitation of hepatitis C virus RNA. J Virol Methods. 2002;2:119–128. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(02)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Zhang T, Douglas SD, et al. Morphine enhances hepatitis C virus (HCV) replicon expression. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(3):1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63476-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frese M, Schwarzle V, Barth K, et al. Interferon-gamma inhibits replication of subgenomic and genomic hepatitis C virus RNAs. Hepatology. 2002;35(3):694–703. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang T, Lin RT, Li Y, et al. Hepatitis C virus inhibits intracellular interferon alpha expression in human hepatic cell lines. Hepatology. 2005;42(4):819–827. doi: 10.1002/hep.20854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takaoka A, Yanai H. Interferon signalling network in innate defence. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8(6):907–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA. Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75(2):163–189. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0603252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu C, Zhu H, Tu Z, Xu YL, Nelson DR. CD8+ T-cell interaction with HCV replicon cells: evidence for both cytokine- and cell-mediated antiviral activity. Hepatology. 2003;37(6):1335–1342. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takaoka A, Mitani Y, Suemori H, et al. Cross talk between interferon-gamma and -alpha/beta signaling components in caveolar membrane domains. Science. 2000;288(5475):2357–2360. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hengel H, Koszinowski UH, Conzelmann KK. Viruses know it all: new insights into IFN networks. Trends Immunol. 2005;26(7):396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fitzgerald KA, McWhirter SM, Faia KL, et al. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(5):491–496. doi: 10.1038/ni921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Civas A, Island ML, Genin P, Morin P, Navarro S. Regulation of virus-induced interferon-A genes. Biochimie. 2002;84(7):643–654. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato M, Hata N, Asagiri M, Nakaya T, Taniguchi T, Tanaka N. Positive feedback regulation of type I IFN genes by the IFN-inducible transcription factor IRF-7. FEBS Lett. 1998;441(1):106–110. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foy E, Li K, Wang C, et al. Regulation of interferon regulatory factor-3 by the hepatitis C virus serine protease. Science. 2003;300(5622):1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.1082604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]