Abstract

Biological actions resulting from phosphoinositide synthesis trigger multiple downstream signalling cascades by recruiting proteins with pleckstrin homology domains, including phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 and protein kinase B (also known as Akt). Retrospectively, more attention has been focused on the plasma membrane-associated interactions of these molecules and resulting cytoplasmic target activation. The complex biological activities exerted by Akt activation suggest, however, that more subtle and complex subcellular control mechanisms are involved. This review examines the regulation of Akt activity from the perspective of subcellular compartmentalization and focuses specifically upon the actions of Akt activation downstream from phosphoinositide synthesis that influence cell biology by altering nuclear signalling leading to Pim-1 kinase induction as well as hexokinase phosphorylation that, together with Akt, serves to preserve mitochondrial integrity.

Keywords: Heart, Cardiomyocyte, Akt, PKB, Mitochondria, Pim-1, Kinase, Nucleus

1. Introduction

Akt serves as a critical nexus of integration between cellular stimuli and subsequent adaptive responses, and the pervasiveness of Akt signalling has made it one of the most extensively characterized kinases in the myocardium. The substrates of Akt influence every aspect of cellular functions including not only growth, survival, and proliferation, but also metabolism, glucose uptake, gene expression, and cell–cell communication via initiation of paracrine and autocrine factor production. The explosion of our experimental and practical understanding of molecular signal transduction in both normal and pathological conditions revealed Akt as a canonical example of the complexity that lies beneath integration of signals for maintenance of homeostasis.1 To accomplish this diverse, intricate, and wide-ranging set of functions, Akt traverses the cell interior with regulated localization that places the kinase in specific subcellular compartments in a defined temporal sequence.2–5 Much of the literature has focused upon Akt activity and functional effects in the cytoplasm and at the plasma membrane and this has been recently and thoroughly reviewed.6–9 It is becoming increasingly clear, however, that activity of Akt in additional subcellular compartments is a key determinant of its biological effects. This review focuses upon two such subcellular sites for Akt action: the nucleus and the mitochondria. The nascent nature and limited number of studies regarding consequences of nuclear or mitochondrial Akt activity in the myocardium requires extrapolation from non-cardiac literature to present a coherent emerging picture of this rapidly advancing area of investigation. Thus, this review encompasses a mixture of more established studies from non-cardiac cells as well as relevant publications that expand our understanding of nuclear and mitochondrial Akt biology into the realm of cardiomyocyte biology. To provide a contextual background for Akt activation leading to effects in subcellular compartments, we begin with a brief overview of the well-established cytoplasmic Akt activation paradigm.

2. Akt activation at the plasma membrane and cytoplasmic targets

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) catalyses the formation of 3′ phosphorylated phospholipids which play a ubiquitous role in cell growth, proliferation, survival, migration, metabolism, and other biological responses.10 Class I PI3Ks are activated by receptor tyrosine kinase/cytokine receptor activation (class IA and PI3Kα, β, and δ) or by G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) (Class IB and PI3Kγ), leading to increased phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5) trisphosphate (PIP3) levels. Akt inactivity is maintained by interaction between its PH domain and kinase domains.11 Mammalian cells possess three closely related Akt genes that produce the eponymous protein products of Akt 1 (PKBα), Akt2 (PKBβ), and Akt3 (PKBγ). These isoforms exhibit functionally different effects in non-myocytes (reviewed in ref.6) as well as in cardiomyocytes.12–14 Pursuant to receptor stimulation, elevation of PIP3 level induces concentration of molecules possessing PH domains at the plasma membrane promoting interaction between phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1) and Akt resulting in allowing PDK1 to phosphorylate Akt at the T-loop Thr308 residue.15,16 Activated Akt remains in activated form upon dissociation from the plasma membrane and accumulates both in the cytoplasm and the nucleus.11 A second phosphorylation within a C-terminal hydrophobic motif at Ser473 is mediated by the mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) empowering Akt to be fully activated.17,18 Activated Akt is then able to phosphorylate a plethora of downstream targets that run the gamut of cellular regulatory agents controlling glucose transport, glycolysis, glycogen synthesis, and suppression of gluconeogenesis to protein synthesis, cell size enlargement, cell cycle progression, repression of apoptosis, and preservation of mitochondrial integrity. Notable players phosphorylated by Akt include well-known effectors such as glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3), PTEN, Mdm2, PRAS40, BAD, and the FOXO class of transcription factors that help guide the specificity of Akt dependent signalling as detailed in a number of recent review articles.1,6,7,9,19,20

There is abundant evidence that activated Akt prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by multiple pathological insults including ischaemia reperfusion,21,22 pressure overload,23 hypoxia,24 hypoglycaemia,25 or cardiotoxic drugs.26 Thus, the net result of PI3K activity is enhanced Akt activation that impacts cardiomyocyte survival, remodelling, and myocardial proliferation.27,28 Constitutive and sustained Akt activation resulting from adenoviral gene transfer or transgenic expression induces hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes through phosphorylation of target substrate molecules which are predominantly located in the cytoplasm and leads to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in vivo.29,30 These observations suggest that not only the extent of Akt activation, but also spatio- and temporal aspects are important factors to understand the role of Akt in physiological and pathophysiological setting.

Cellular targets of Akt mediating pro-proliferative and anti-apoptotic effects reside within the nuclear compartment.31–33 Effects of nuclear Akt signalling have been studied by our group through the use of a modified Akt expressed in wild-type (non-activated) form, but targeted to the nucleus by incorporation of a nuclear localization signal (Akt-nuc).27 Akt-nuc exerts significant cardioprotective, proliferative, and inotropic effects in cardiomyocytes27,28,34 without induction of hypertrophic response both in vitro and in vivo.23 Akt-nuc shows these biological activities reminiscent of physiological stimulation by insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1)21,35–37 or estrogenic38–40 stimulation despite being targeted directly to the nucleus rather than being initiated via the conventional paradigm of membrane-associated activation and subsequent nuclear accumulation.10 Remarkably, genetic deletion of Akt results in exaggerated hypertrophic remodelling in response to pathological challenge,13 consistent with the anti-hypertrophic effects observed with nuclear-targeted Akt. These effects are distinctly divergent from those reported in earlier studies of transgenic cardiac-specific Akt activity in which phosphomimetic or myristoylated forms of Akt were found to induce alterations in myocardial structure and function consistent with hypertrophic remodelling and/or cardiomyopathy.29,30,41–43 The findings that the salutary effects of nuclear Akt accumulation in cardiomyocytes are more closely resemble those seen with physiological activity of Akt lends support to the postulate that biologically relevant targets of Akt action are located within the nuclear compartment.

3. Nuclear Akt

The concept that nuclear Akt accumulation plays a critical role in myocardial biology has been advanced in several published studies and editorials.23,27,28,34,44–50 In the first of a series of nuclear-targeted Akt-related publications, a wild-type Akt was used to maintain near-physiologic levels of kinase activity with targeting mediated by a concatameric nuclear localization sequence. Nuclear accumulation of Akt was shown to produce profound anti-apoptotic activity without evidence of hypertrophic growth in either cultured cardiomyocytes or genetically engineered mice that specifically expressed nuclear targeted Akt.27 Inhibition of apoptosis was comparable to that seen for myristoylated Akt, and prevention of ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R) damage in vivo was comparable to the potent effect of pre-conditioning. Expression of nuclear-targeted Akt mimicked beneficial characteristics of IGF-mediated protection without maladaptive hypertrophy or undesirable paracrine-signalling side effects. Subsequent publications demonstrated that the nuclear accumulation of Akt is anti-hypertrophic,23 in agreement with findings obtained with Akt knockout mice in which there was exaggerated hypertrophy in response to pathologic challenge.13 Interestingly, the proliferation of myocardial stem and progenitor cell populations is also enhanced by myocardial-specific nuclear Akt expression, casting new light upon the implementation of Akt activity as a molecular interventional approach for treatment of cardiomyopathic damage resulting from acute injury, chronic stress, or the debilitating changes of aging.28,49

While the mechanistic basis and consequences of nuclear Akt accumulation remain the subject of ongoing investigations, initial forays into this area indicate a range of possibilities as diverse and multifaceted as those uncovered for cytoplasmic effects. Nuclear import of Akt in cardiomyocytes may be facilitated by interaction with the cytoskeletal protein zyxin, which interacts with Akt and constitutively shuttles through the nuclear compartment.47 Studies in cancer cell lines demonstrate that Akt is actively transported to the nucleus and that this appears to be conformation dependent, although the functionality of an embedded nuclear export sequence within Akt remains uncertain.51,52 The oncogenic protein TCL-1 promotes Akt activation and nuclear translocation in T cell leukaemia.53 There are many cellular targets of Akt that are involved in nuclear signalling events, including (but are not limited to) regulators of cell survival and senescence such as S6 kinase,54 forkhead transcription factors,55–57 BRCA1,58,59 p21Cip1/WAF,60–62 p27,63–66 Mdm2,61,67 HDM2,68 YAP,69 CDC25,70 WEE Hu,71 ERKs via PEA-15,72 and tuberin.73–76 Nuclear accrual of Akt presumably serves to inhibit, enhance, or modulate localization77,78 for these effectors. Moreover, nuclear accumulation of Akt induces expression of Pim-1 kinase, which has been shown to be responsible for cardioprotective properties of Akt50,79 as discussed in detail later in this review. Of course, effects involving the nuclear activities of GSK80–82 and PTEN20 are also likely, but the specifics about these interactions in the nuclear compartment of cardiomyocytes remain obscure. Maintenance of Akt in activated form may depend in part upon heat shock proteins (Hsp) including stabilization by interaction with Hsp 9083,84 or activation facilitated by interaction with Hsp2785 as well as Hsp20,86 with the latter found to be cardioprotective via increased Akt activity against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. The control of cell cycle and commitment or pluripotency may also be influenced by Akt nuclear actions. Transitions in the nuclear vs. cytoplasmic localization of Akt correlate with cell cycle phases in Rat1 cells.5 Introduction of Akt dramatically alters the outcome of nuclear reprogramming experiments by enhancing pluripotency of cell fusion or diminishing the developmental potential of somatic cell nuclear transfer.87 Although much of the aforementioned studies were performed in non-cardiac systems, the implications and future directions for nuclear Akt signal transduction and the implications for influencing cardiomyocyte biology are abundantly clear.

3.1. Regulation of nuclear Akt activity: phosphoinositide signalling?

Cellular targets of Akt mediating pro-proliferative or anti-apoptotic effects are known to reside within the nuclear compartment.31–33 Nuclear-targeted Akt shows these biological activities despite being targeted directly to the nucleus rather than the conventional paradigm of membrane-associated activation and subsequent nuclear accumulation.10 The inherent activity of nuclear-targeted Akt may depend upon a nuclear PI3K/PDK1 signalling network present in cardiomyocytes that can be augmented in response to cardioprotective stimulation. Precedents in the literature support the existence of a nuclear phosphoinositide signalling mechanism that exerts significant influences upon nuclear Akt signalling. It is important to stipulate that the following construction for nuclear regulation of Akt activity remains to be confirmed in the cardiomyocyte context, but the abundance of preceding knowledge serves as a valuable guide to design ongoing and future studies in this area.

Although the plasma membrane is the major site for phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5) trisphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3) accumulation, several different nuclear phosphatidylinositol phosphates (PIPs) independent of the cytosolic pool have been identified thus far including PI(3,4,5)P3 generated by Type I PI3K.88,89 This nuclear PI(3,4,5)P3 is consistent with prior reports of intra-nuclear Type I PI3K,90–93 a regulatory GTPase called PIKE,94–96 and PI(3,4,5)P3-specific phosphatases SHIP2 and PTEN.97 Cell culture studies suggest independent regulation of the nuclear pool separate from cytosolic PTEN-mediated metabolism.98 Inferential evidence for nuclear lipid second messenger signalling in rat brain shows a PI(3,4,5)P3-binding protein that accumulates in the nucleus with export mediated by constitutively activated PI3K.99 The nuclear signalling connection between PI(3,4,5)P3 and Akt could be mediated through nucleophosmin/B23, a nuclear PI(3,4,5)P3 receptor that binds to Akt.100 In turn, Akt binding prevents proteolytic cleavage of nucleophosmin/B23 that allows for enhanced anti-apoptotic signalling.101

The paradigm of phospholipids signalling primarily at the plasma membrane has shifted to incorporate an independent nuclear phospholipid cycle102–104 as well as plasma membrane-associated events being initiated by a nuclear phosphoinositide signalling cascade.105–107 Nuclear localization of components of the PI3K signalling pathway was first reported in 1994 when PI3K was found to translocate to the nucleus of PC12 cells upon nerve growth factor treatment.105 Following this initial report, similar results were described in various cell types (HepG2 cells, osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells, and others) after stimulation by insulin, IGF-1, and platelet derived growth factor.90,92,108 PI3K is not the only Akt-regulatory component found to shuttle or exist in the nucleus; PDK1 and PTEN also translocate to the nucleus upon stimulation or to reside in the nucleus under basal conditions.106,107,109,110 The idea of a PI3K/Akt pathway present in the nucleus of cardiomyocytes under normal conditions, or being recruited after stimulation, adds another level of regulation for the phosphorylation of Akt and its targets in the nucleus. Several studies have shown that Akt phosphorylation is not required for nuclear translocation,52,111,112 which makes the idea of nuclear activation of Akt even more appealing113 as supported by studies in continuous cultured cell lines with GFP-tagged Akt constructs.51

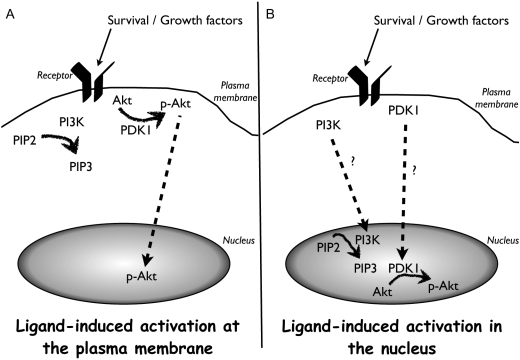

Specifically in the context of the cardiomyocyte, our group has examined the nuclear accumulation of PI3K and PDK1 in response to cardioprotective stimulation.114 Stimulation with atrial natriuretic peptide previously shown to stimulate nuclear Akt accumulation47 resulted in concomitant nuclear accumulation of both PI3K and PDK1. Similar findings of nuclear PI3K accumulation were observed in the border zone surrounding infarcts in mice. Thus, it seems reasonable to posit that a dynamically regulated nuclear-associated signalling cascade for Akt activation involving PI3K and PDK1 operates in cardiomyocytes as hypothetically depicted in Figure 1***.

Figure 1.

Activation of Akt in the cytoplasm (A) vs. activation of Akt-nuc in the nucleus (B). (A) Diagram depicting the classical activation pathway of Akt at the plasma membrane. Upon stimulation of tyrosine kinase/cytokine receptors, PI3K catalyses the phosphorylation of PIP2 into PIP3. Increased PIP3 levels recruit PDK1 to the membrane resulting in its activation and subsequent Akt phosphorylation. (B) Hypothesized activation of Akt in the nucleus. Upon stimulation of membrane receptors, PI3K and PDK1 translocate onto nuclear membrane or into the nucleus where they aid in phosphorylation of nuclear Akt.

3.2. Pim-1 kinase downstream of nuclear Akt activity

Pro-survival and proliferative effects of Akt activity in the myocardium are well documented.21,27,115 However, recent evidence indicates that these actions previously ascribed to Akt are actually mediated by a downstream kinase called Pim-1,50,79 one of a three-member family of serine/threonine kinases belonging to the calmodulin-dependent protein kinase related group.116,117 Pim-1 was originally identified as a proto-oncogene and subsequently found to be a highly conserved serine/threonine kinase. Unlike other serine/threonine kinases (e.g. Akt, MAPK, PKA, or PKC), Pim-1 phosphotransferase activity is not regulated by upstream kinases—it is active in nascent translated form. Thus, Pim-1 activity is regulated by concerted control of gene transcription, mRNA translation, and protein degradation. The target phosphorylation consensus sequence for Pim-1 is found in proteins mediating transcription, cell growth, proliferation, and survival. While Pim-1 overexpression alone is not highly oncogenic, it does predispose cells to transformation upon exposure to mutagens.118,119 In general, Pim-1 up-regulation enhances cell survival, whereas loss of Pim-1 increases apoptotic cell death. The protective effect of Pim-1 is dependent upon kinase activity as borne out by experiments using a dominant negative kinase dead mutant construct.120,121 Occasional exceptions wherein Pim-1 activity increases cell death seem to result from differences in the cellular backgrounds where Pim-1 was studied. Increased Pim-1 expression also associated with cellular differentiation122–124 as well as proliferation.125,126

Pim-1 expression is stimulated by a variety of hormones, cytokines, and mitogens, many of which are associated with cardioprotective signalling.127,128 These multiple inductive stimuli lead to an accepted survival kinase in the myocardium, Akt/protein kinase B (PKB). However, the connection of Akt-mediated effects to Pim-1 mediated signalling in the myocardial context had been overlooked. Pim-1 shares homology with two related family members that have largely overlapping functions named Pim-2 and Pim-3, although the latter two isoforms are not highly expressed in the heart.50 There were compelling reasons to examine Pim-1 downstream of Akt signalling based upon observations derived from fields of cancer biology and haematopoiesis. Expression of Pim-1 is increased by Akt activation129 and studies using LY294002 to block PI3-K activity were also inadvertently inhibiting Pim-1 kinase activity as well.130 Despite some parallels between Pim-1 and Akt, these kinases exhibit distinct effects in regulation of cell growth and survival.131

Independent aspects of Pim-1 mediated signalling are waiting to be teased apart from overlaps with Akt using knockout mouse lines in conjunction with overexpression approaches, thereby providing new insight regarding regulation of myocardial survival and proliferation. Such studies with haematopoietic cells have revealed that Pim-2 and Akt are critical components of overlapping but independent signalling pathways responsible for enhancement of growth and survival.131,132 Mouse lines engineered with deletion of Pim-1 or triple knockouts deficient for all Pim kinases are viable without severe phenotypic effects.133

Last year, our group extended observations of Pim-1 expression to include the myocardium, where Pim-1 expression is found in cardiomyocytes of the postnatal heart and is down regulated within a few weeks after birth.50 Induction of Pim-1 occurs after pathologic challenge to the adult heart, with accumulation and persistence of Pim-1 in surviving myocytes that border areas of infarction. Cardiac-specific expression of Pim-1 was highly protective in response to infarction challenge, whereas genetic deletion of Pim-1 rendered mice more susceptible to infarction damage despite significant compensatory increases in Akt expression and phosphorylation. These findings point to Pim-1 as a critical downstream participant in Akt-mediated cardioprotection, with implications for Pim-1 as a participant in survival, proliferative, and reparative processes previously associated with Akt activity as summarized in Figure 2***. Future studies expanding upon the role of myocardial Pim-1 may lead to more focused avenues for intervening in cellular processes rather than Akt, since Pim-1 activity can be directly regulated by expression level and may not have the widespread and often deleterious impact of altered Akt signalling previously observed in the heart.29,30,115,134–136

Figure 2.

Summary of the multifaceted effects mediated by Pim-1 in cardiomyocytes and in the myocardium as delineated in published studies.50,79

3.3. Tying Pim-1 to preservation of mitochondrial integrity

The apparent conundrum of anti-apoptotic actions mediated by nuclear accumulation of Akt can be readily explained, at least in part, by cytosolic effects of Pim-1. The list of target molecules for Pim-1 kinase continues to accumulate new members every year, many of which regulate cell cycle progression and apoptosis. In the context of this review, the capacity of Pim-1 to inactivate pro-apoptotic Bad protein via phosphorylation and enhance Bcl-2 activity132,137,138 is reminiscent of prior investigations of cardiomyocyte survival signalling.139,140 Evidence supporting a critical role for Pim-1 as a mediator of mitochondrial-based cardioprotection is further supported by recent studies in our laboratory that show Pim-1 activity enhances mitochondrial resistance to calcium-induced swelling and inhibits cytochrome c release in response to apoptotic stimuli (Sussman, unpublished results).

4. Mitochondrial Akt

Since mitochondria act as integrators of multiple cellular conditions reflecting physiological and genomic stresses, it is reasonable to expect that kinase signalling mechanisms influencing cell survival impinge either directly or indirectly upon mitochondrial integrity. Indeed, a cornucopia of studies have documented the influence of each major kinase signalling pathway including PKA, PKC, ERK, JNK, p38, and Akt on mitochondrial activity.141 The connection between IGF signalling, Akt, and mitochondrial protection points to the interplay of Akt with mitochondria.36 Moreover, the cardioprotective of Akt has been suggested to depend upon translocation from the cytosol to mitochondria142 where it inhibits opening of the permeability transition pore to maintain mitochondrial integrity.143–145 As the role of Akt in protection of mitochondrial integrity has recently been reviewed in detail.146 Accordingly, this section will summarize basic principles of intrinsic cell death and introduce recent advances regarding the role for hexokinases and other effectors in Akt-mediated mitochondrial protection in the myocardium.

4.1. Mitochondrial death pathway

Cardiomyocyte death is an established contributor to the cardiac pathophysiology that occurs with I/R injury and the development of heart failure.147–153 There are two major apoptotic pathways referred to as extrinsic (death receptor pathway) and intrinsic (mitochondrial pathway). The mitochondrial death pathway is the main executor of induction of apoptosis as well as necrosis in response to variety of stress signals in the heart; thus, we will focus on the mitochondrial death pathway in this review.

Several lines of evidence demonstrate that cardiomyocyte injury induced by I/R results from increased cytosolic Ca2+ and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which subsequently leads to opening of the mitochondrial PT-pore.152,154–157 The PT-pore is a mega channel which spans the inner mitochondrial membrane and outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM). Ca2+-induced PT-pore opening was first reported in the 1970s. Upon its opening, the PT-pore allows permeation of solutes up to 1500 Da, resulting in dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential (which usually drives ATP production), mitochondrial swelling, and rupture of OMM. Opening of the PT-pore eventually induces necrotic and apoptotic cell death, contributing to heart diseases.148,152,154–159 The type of cell death induced by the PT-pore is dependent on the availability of cellular ATP, and recent evidence suggests that PT-pore opening primarily induces necrosis. The PT-pore has been postulated to be composed of a voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT), cyclophilin D (Cyp-D), and hexokinase-II (HK-II).152 However, the molecular composition of the PT-pore is still not clear. Recent genetic studies indicate that VDAC and ANT are not essential for PT-pore opening.160,161 In contrast, mitochondria isolated from Cyp-D knockout (KO) mice are resistant to Ca2+ overload-induced PT-pore opening. Two different groups have demonstrated that the Cyp-D KO mouse heart is resistant to I/R injury and Ca2+/ROS induced necrotic cell death,148,159 lending further credence to the hypothesis that opening of the PT-pore is a critical mediator in heart disease.

Bcl-2 family proteins play a central role in controlling mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. The pro-apoptotic group of Bcl-2 family proteins including BAX and BAK are activated under stress conditions and elicit mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), resulting in release of apoptotic molecules such as cytochrome c, apoptosis inducing factor (AIF), Smac and HrtA2/Omi, subsequent caspase-9/caspase-3 activation, and the development of apoptosis. Pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins (Bad, BID, BIM, and PUMA) promote MOMP by activation of BAX/BAK or by antagonizing inhibitory effects of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL on BAX/BAK.88

Interactions between the PT-pore and the Bcl-2 family proteins have been also postulated although this idea is still controversial. Thus, Bax does not affect Ca2+ induced PT-pore opening in isolated mitochondria162 nor does overexpression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein inhibit Ca2+ mediated PT-pore.163 Knockdown of Cyp-D prevents the PT-pore and Ca2+-mediated necrotic cell death, but not apoptotic cell death.148 Therefore, it appears that PT-pore and Bcl-2 family proteins independently regulate mitochondrial permeability. Nonetheless, recent studies have unveiled non-mitochondrial actions of Bcl-2 family proteins. Growing evidence suggest that apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins can localize to ER/SR and increase ER/SR Ca2+ loading, resulting in subsequent induction of supraphysiological level of Ca2+ release and PT-pore opening.164–167 Thus, Ca2+ signalling in between ER/SR and mitochondria links these two distinct cell death mechanisms as observed in Nix, a BH-3-only protein, mediated cell death in cardiomyocytes.167

4.2. Akt, cardioprotection, and mitochondria

Akt plays a major role in cell survival signal in many cell types21,24,168 and as indicated above, Akt is protective against I/R injury in the heart. Initial and direct evidence of Akt-mediated cardioprotection was demonstrated by two groups by using gene transfer of WT or constitutively activated Akt.21,24 It has been also shown that Akt activated in response to receptor stimulations such as receptor tyrosine kinases,21,24 glycoprotein 130,169–171 and GPCRs172–176 can also confer protection in the heart. Akt activation by insulin or S1P decreases I/R damage in the isolated perfused heart or in vivo176–178 and Akt activation has been implicated in cardioprotection mediated by pre-conditioning.140,179–181 Both chronic (transcriptional) and acute (posttranscriptional) effects of Akt are implicated in its Akt-mediated cardioprotective effect. The cardioprotective effects of Akt activation by agonists observed in I/R models occur within minutes to hours. These are unlikely to be mediated through transcriptional or translational events, but likely result from modification of proteins by Akt-mediated phosphorylation.

As mentioned in the introduction, activated Akt translocates to and executes diverse cellular effects in various subcellular compartments.3,4,45,182,183 Visualization of Akt activation using FRET-based Akt activity reporters in non-cardiac cells has demonstrated that activated Akt translocates to mitochondria and the nucleus.3,182 Translocation of activated Akt to mitochondria was initially reported in neuronal cells4 and has more recently been observed in cardiomyocytes stimulated by LIF or late pre-conditioning.142,183 Therefore, Akt could prevent cell death not only through modulation of cytosolic molecules or effects at the nucleus (as discussed above), but also through direct effects at mitochondria.

5. Akt and mitochondrial protection

5.1. Bcl-2 family proteins

The ability of Bcl-2 pro-apoptotic proteins to mediate induction of apoptosis through MOMP was described above. Bad, a BH3-only apoptotic protein, was the first Bcl-2 family protein to be discovered as a Akt target molecule. Akt phosphorylates Bad at Ser136 and this leads to dissociation of Bad from protective Bcl-2 proteins Bcl-XL, resulting in inhibition of Bax/Bak mediated pore formation.184,185 Bad phosphorylation by Akt agonists such as insulin, cardiotrophin-1, and LIF has also been reported in the heart.26,169,177,186

Akt has also been reported to phosphorylate and inhibit Bax. Yamaguchi and Wang187 first reported using FL5.12 cells that phosphorylation of Bax by Akt prevents the conformational change in Bax associated with its activation as well as its translocation to mitochondria. Subsequent studies have found that Akt phosphorylates Bax at Ser184 in yeast and neutrophils.188,189 A previous study demonstrated that Bax ablation protects isolated hearts against I/R injury, suggesting that Bax plays a role in cardiac injury.190 However, to our knowledge, Bax phosphorylation by Akt has not been reported in cardiomyocytes and thus the role of regulation of Bax by Akt-mediated phosphorylation in the heart is not clear.

In addition to direct modulation of Bcl-2 family proteins by phosphorylation, it has been reported that Akt regulates expression levels of protective Bcl-2 family proteins by multiple pathways. LIF treatment inhibits doxorubicin-induced decreases in Bcl-XL expression in cardiomyocytes26 and it has been also reported that VEGF induces Bcl-2 upregulation through Akt and PKCϵ in endothelial cell.191,192 Bcl-2 levels are decreased by I/R in the heart and this is prevented by pre-conditioning through Akt activation.68 Thus, Akt appears to preserve protective Bcl-2 family proteins although it is still not clear whether this occurs through transcriptional regulation or whether protein degradation is prevented.

5.2. GSK-3ß

GSK-3 is a Ser/Thr protein kinase that was originally identified as a key regulator of glycogen synthesis.193 Subsequently, it has been shown to regulate many cellular functions, including regulation of cell death. There are two isoforms, GSK-3α and -3β and Akt phosphorylates GSK-3α and -β at Ser21 and Ser9, respectively, inhibiting GSK kinase activity.194 The role of GSK-3β in the heart has been extensively studied. An initial study in the heart from Murphy’s laboratory demonstrated that the inhibition of GSK-3β is cardioprotective against I/R.180 Sollott and co-workers145 showed that GSK-3β could localize at mitochondria and that inhibition of GSK-3β was protective through PT-pore inhibition in ventricular myocytes. Expression of kinase inactive form of GSK-3ß protects rat ventricular myocytes in vitro195 and dominant negative GSK-3ß TG mice show reduced apoptosis and fibrosis during transverse aortic constriction.196 A recent study using transgenic mice expressing a form of GSK-3ß that cannot be phosphorylated at the site of Akt phosphorylation (GSK-3ß-S9A) has clearly shown that phosphorylation at this site is critical in inhibition of PT-pore opening by post-conditioning in the heart.197 These results suggest that phosphorylation of GSK-3β by Akt at Ser9 is a critical mechanism for Akt-mediated cardioprotection. Protection observed in GSK-3β-S9A TG mice is suggested to be Cyp-D independent197 and occur upstream of the PT-pore. A recent study has proposed a model in which GSK-3 inhibition decreases VDAC2 phosphorylation and thus decreases mitochondrial ATP consumption during ischaemia, this contributes to cardioprotection by GSK-3 inhibition.198 It has also been shown that GSK-3ß phosphorylates VDAC and disrupts mitochondrial binding of HK-II in non-cardiac cells.199 Whether these are truly the only mechanism by which inhibition of GSK-3ß prevents PT-pore opening is still not clear because role of VDAC in PT-pore has been questioned.

Recent studies using non-phosphorylatable mutants of GSK-3α and -β knockin mice (KI mice) demonstrate unexpected results. Matsuda et al.80 suggested that phosphorylation of GSK-3α plays a compensatory role, whereas phosphorylation of GSK-3β mediates pathophysiological responses to pressure overload. Regarding cell death, the authors observed that TAC induced apoptosis was enhanced by knockin of a dominant interfering GSK-3α, GSK-3α(S21A) and inhibited by knockin of GSK-3β(S9A), further suggesting that phosphorylation of GSK-3β at Ser9 is pro-apoptotic. This is a sharp contrast to the conclusions cited above using GSK-3β(S9A) TG mice where post-conditioning failed to protect heart.197 Another recent study demonstrated that pre-conditioning and post-conditioning protected heart against I/R even in GSK-3α(S21A) and GSK-3β(S9A) double KI mice, suggesting that neither GSK-3 isoform is required for pre- and post-conditioning mediated cardioprotection.200 Interestingly, this study showed the ability of insulin to prevent the PT-pore opening was preserved in double KI mice, suggesting another target of Akt for the PT-pore inhibition. Taken together, there remains controversy with regard to whether phosphorylation of and inhibition of GSK-3β is cardioprotective. These conflicting data might be due to different experimental settings, such as animal models (KD or S9A-TG vs. S21A/S9A KI mice), insults (TAC, ex vivo I/R and in vivo I/R), and methods for detection of the PT-pore opening (mitochondrial membrane potential detection, mitochondrial swelling assay and calcium retention capacity, etc.).

Regarding Bcl-2 family proteins and GSK-3, several studies have reported that GSK-3 has apoptotic effect through regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins. It has been shown that GSK-3ß phosphorylates VDAC and disrupts mitochondrial binding of HK-II in non-cardiac cells, facilitating BAX binding to VDAC and apoptosis.199 Green and co-workers201 first found that inhibition of GSK-3ß by Akt leads to stabilization of MCL-1, an anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family protein, by preventing its ubiquitination and degradation. A similar upregulation in MCL-1 level by inhibition of GSK-3ß has been reported in cardiomyocytes.196 In addition, mTOR complex-1 (mTORC1), which is activated by Akt, has been reported to translationally control Mcl-1 expression and promotes tumour cell survival.202 Inhibition of GSK-3 by Akt-mediated phosphorylation may contribute to cardioprotection through regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins and apoptosis.

5.3. Hexokinase (HK)

5.3.1. Hexokinase and protection

While hexokinase is normally considered for its role in phosphorylating glucose to glucose-6-phosphate, driving glycolysis, HK-I and HK-II have mitochondrial binding motifs at their N-termini203 and a significant fraction of total cellular HKs is associated with mitochondria.203,204 Tumour cells show increased Akt activity which facilitates tumour cells survival, and also enhanced glycolysis due to upregulation of HK expression.205,206 It is well known that Akt regulates metabolism through glucose uptake and it appears that energy metabolism and cell survival utilize convergent pathways in many organ systems.206,207

The importance of mitochondrial HKs in cell survival has only recently been considered, initiated by studies in the field of cancer research (see reviews;206,208–210). HK-I is ubiquitously expressed and HK-II is found to be predominantly expressed in insulin sensitive tissues including heart. In epithelial cell lines, growth factor (HB-EGF) was shown to increase HK activity and its protective effect against oxidative stress was mimicked by overexpression of HK-I.211 Overexpressed HK-II also showed mitochondrial distribution, preserved mitochondrial integrity, and conferred protection under oxidative stress.211,212 Further, recombinant HK-I, but not yeast HK which lacks mitochondrial binding motif, inhibited Ca2+-induced mitochondrial swelling.213 Conversely, dissociation of HK from mitochondria was shown to sensitize rat1a fibroblast to apoptotic cell death214 or to induce PT-pore opening in Hela cells.215 These results indicate that mitochondrial HKs are important in regulation of mitochondrial integrity and protective in various cell types. Indeed, very recent works including studies from one of our laboratories demonstrated that mitochondrial HK-II contributes to preservation of mitochondrial integrity in cardiomyocytes (Figure 3). Ardehali’s group demonstrated that overexpression of HK-I or HK-II prevented mitochondrial membrane depolarization induced by H2O2 in neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes, and this protection was significantly blunted when mitochondrial binding motif deletion mutants of HK-I or HK-II were expressed,216 suggesting that mitochondrial HKs could be cardioprotective. In contrast to overexpression of HK, it has been also shown that dissociation of HK-II from mitochondria increased PT-pore susceptibility to ROS in intact adult rat ventricular myocytes.215 Our study suggested that mitochondrial HK-II is important in Akt mediated cardioprotection as described below.183 Thus, mitochondrial HK-II would be an important regulator of the PT-pore in the heart.

Figure 3.

Akt preserves mitochondrial integrity against stress at multiple levels.

5.3.2. Hexokinase as an Akt target

Several seminal studies have established mitochondrial HK-II as downstream effector by which Akt inhibits cell death.206,208,214,217 A study by Hay and co-workers was among the first to link mitochondrial HK-II to Akt-mediated mitochondrial protection. This work demonstrated that myr-Akt overexpression leads to increased mitochondrial HK activity and protects Rat1a fibroblasts against growth factor withdrawal and UV exposure and that ectopic HK-I expression mimicked the ability of Akt to inhibit apoptosis.218 Our recent study using neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) and isolated mitochondria from adult mouse heart demonstrated that mitochondrial HK-II also plays a central role in Akt-mediated protection in the heart.183 Akt activation by LIF in cardiomyocytes leads to active Akt accumulation at mitochondria, and increases the phosphorylation of mitochondrial HK-II, which has Akt consensus sequence (RxRxxS/T). This results in increased association of HK-II with mitochondria and confers protection against PT-pore opening induced by oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes or against Ca2+ overload in permeabilized cardiomyocytes or isolated mitochondria.183 Conversely, we demonstrated that dissociation of HK-II from mitochondria diminishes LIF/Akt-mediated mitochondrial protection against oxidative stress. Notably, a recent report demonstrates that ischaemic pre-conditioning, as well as insulin and morphine (interventions known to activate Akt) increase mitochondrial hexokinase activity in the heart.219 An immunogold labelling study in the heart has further demonstrated that insulin increases mitochondrial association of HK-I and HK-II but the increase is greater in HK-II than HK-I, suggesting the differential regulation of these two mitochondrial HKs distribution.220 This is of particular interest as we found the Akt consensus sequence in mouse, rat, and human HK-II, but not in HK-I (or HK-III). Thus, Akt mediated phosphorylation and regulation of hexokinase distribution might be specific to HK-II. It remains to be determined whether HK-II is a mediator of cell survival in the intact heart, where HK-II is abundantly expressed. It has been shown that knockout of HK-II causes embryonic lethality and a partial KO (heterozygous) mouse has been utilized for metabolic studies. To determine the protective effects of mitochondrial HK-II in the heart, it will be necessary to develop and analyse cardiac-specific and inducible HK-II KO mice.

HK interacts with apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins such as Bax and Bid. Specifically, HK-II was shown to interfere with the ability of Bax to bind to mitochondria and release cytochrome c.217 The Akt-induced increase in mitochondrial HK-II is also associated with loss of t-Bid-mediated BAX and BAK activation at mitochondria.221 These effects of HK-II on Bcl-2 family proteins have not been demonstrated in the heart, but it appears that the Akt/HK-II axis may have multiple targets to protect mitochondria.

5.4. Downstream inhibition after mitochondrial events

Akt has several additional targets through which it might inhibit development of apoptosis. The AIF is released from mitochondria, translocates to the nucleus, and is responsible for executing chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation. This occurs in ventricular myocytes in response to oxidative stress.222 A recent study shows that overexpression of active Akt inhibits the translocation of AIF to the nucleus in response to the pro-apoptotic lipid ceramide in neuroblastoma cells.223

Akt has also been reported to phosphorylate and inhibit HtrA2/Omi activity.224 HtrA2/Omi is mitochondrial serine protease which is released into the cytosol in response to stress, and binds to and inhibits IAPs (inhibitor of apoptotic proteins); this prevents caspase inhibition mediated by IAPs.

Once cytochrome c is released from mitochondria, it forms a molecular complex Apaf-1, dATP and procaspase-9, called apoptosome. After the formation of apoptosome, procaspase-9 is cleaved and activated, and this in turn activates downstream caspase, caspase-3. Human procaspase-9 has been shown to be phosphorylated by Akt, resulting in its inactivation.225 This phosphorylation site, however, is not conserved in rat or mouse, and thus this is animal species dependent.

5.5. Upstream inhibition of mitochondrial events; cytosolic Ca2+ overload

As mentioned above, Ca2+ overloading of mitochondria induces PT-pore opening, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cell death. Thus, another possible target for Akt mediated protection would be through inhibition of mitochondrial Ca2+ overloading that occurs under pathophysiological conditions. We have observed that H2O2-induced cytosolic Ca2+ overloading in NRVMs is inhibited by LIF pre-treatment, presumably through Akt activation (S. Miyamoto and J.H. Brown, unpublished results). Our earlier studies in NRVMs expressing constitutively activated Gaq demonstrated that there was downregulation of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), decreased Ca2+ extrusion, and induction of apoptosis, when Akt activity was decreased.226 In line with these findings, a recent study suggests that Akt activation upregulates NCX-1 through transcriptional regulation and that this contributes to the Akt mediated protection against hypoxia in PC12 cells.227 It is also well established that pharmacological inhibitors of Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) afford cardioprotection during I/R in vitro and in vivo.228 A recent paper clearly demonstrates that NHE is a target for Akt phosphorylation and that Akt-mediated phosphorylation inhibits cardiac NHE activity.229 The NHE extrudes H+ ions from intracellular space and imports Na+ ions in response to the acidosis that develops under ischaemia. The resulting intracellular accumulation of Na+ in turn inhibits Ca2+ extrusion by NCX or even stimulates Ca2+ influx by NCX (reverse-mode), leading to Ca2+ overloading. Thus, dysregulation of Ca2+ through NHE and NCX appears to be targets for Akt mediated Ca2+ regulation under I/R.

An interesting new finding is that Akt phosphorylates the type-I IP3 receptor (IP3R)230,231 and that this inhibits IP3 mediate Ca2+ release and attenuates induction of apoptosis.231 An Akt consensus sequence is found in all three IP3Rs. In non-cardiac cells, IP3-induced Ca2+ release from the ER has been established as a major Ca2+ source. Dysregulation of this Ca2+ release mechanism has been considered to contribute to mitochondrial Ca2+ overload because of the proximity of release site and mitochondria.232,233 Although the contribution of IP3 receptors to Ca2+ mobilization in the heart has not been fully established, IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores may indeed play a role in regulation of apoptosis, as recently discovered for IP3R contribution to gene expression in cardiomyocytes.234 Notably, IP3R are upregulated in heart diseases,235 suggesting that Akt/IP3R signalling could also play a role in regulating mitochondrial Ca2+ and cardiomyocyte survival under pathophysiological conditions. Interestingly, apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family proteins can localize to ER, induce ER Ca2+ overload, result in supra-physiological levels of Ca2+ release, and eventually lead to mitochondrial Ca2+ overload.236 In cardiomyocytes, Nix, a BH-3 only protein, is shown to localize at SR as well as at mitochondria.167 This recent study suggests that Nix localizes to the SR and increases Ca2+ content of the SR, leading to Ca2+ overload induced PT-pore opening, while Nix at mitochondria induces MOMP in coordination with Bax and Bak. It will be of considerable interest to determine whether other Bcl-2 family proteins regulate SR-mitochondrial Ca2+ crosstalk in the heart, and whether Akt mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 family proteins can lead to change in their ER/SR localization.

6. Conclusions

While the cardiovascular field has been fascinated by Akt signalling and the dramatic effects it has upon the myocardium for well over a decade, it is clear there remains considerably more complexity and subtlety to be teased apart. Akt activation regulates diverse cellular functions including cell survival, growth, and proliferation through transcriptional and post-transcriptional controls. Spatio-temporal dynamics of Akt activity plays a significant role in accomplishment of diverse and wide-ranging functions. Akt activation in response to receptor stimulation leads to mitochondrial translocation of active Akt and preservation of mitochondrial integrity, protecting cardiomyocytes against acute stress such as I/R. Increases in Akt activity in the nuclear compartment regulate gene expression and provide long-lasting cardioprotection against chronic stress including myocardial infarction. Thus, cellular compartmentalization of Akt signalling is responsible for diverse protective effects of Akt in cardiomyocytes. The challenge for future studies is not only to activate Akt, but to accomplish activation in the right place, at the right time, and at the right level to effect downstream responses with important therapeutic implications for the treatment and management of cardiovascular disease.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants [5R01HL067245, 1R01HL091102, 1P01HL085577 to M.A.S. and 1P01AG023071 (to Piero Anversa)] as well as the American Heart Association [930237N to S.M.].

References

- 1.Franke TF. Intracellular signaling by Akt: bound to be specific. Sci Signal. 2008;1:pe29. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.124pe29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao X, Zhang J. Spatiotemporal analysis of differential Akt regulation in plasma membrane microdomains. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4366–4373. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sasaki K, Sato M, Umezawa Y. Fluorescent indicators for Akt/protein kinase B and dynamics of Akt activity visualized in living cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30945–30951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bijur GN, Jope RS. Rapid accumulation of Akt in mitochondria following phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1427–1435. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosner M, Hanneder M, Freilinger A, Hengstschlager M. Nuclear/cytoplasmic localization of Akt activity in the cell cycle. Amino Acids. 2007;32:341–345. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franke TF. PI3K/Akt: getting it right matters. Oncogene. 2008;27:6473–6488. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhaskar PT, Hay N. The two TORCs and Akt. Dev Cell. 2007;12:487–502. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang J, Manning BD. A complex interplay between Akt, TSC2 and the two mTOR complexes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:217–222. doi: 10.1042/BST0370217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duronio V. The life of a cell: apoptosis regulation by the PI3K/PKB pathway. Biochem J. 2008;415:333–344. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foukas LC, Okkenhaug K. Gene-targeting reveals physiological roles and complex regulation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;414:13–18. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calleja V, Alcor D, Laguerre M, Park J, Vojnovic B, Hemmings BA, et al. Intramolecular and intermolecular interactions of protein kinase B define its activation in vivo. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e95. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeBosch B, Sambandam N, Weinheimer C, Courtois M, Muslin AJ. Akt2 regulates cardiac metabolism and cardiomyocyte survival. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32841–32851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513087200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeBosch B, Treskov I, Lupu TS, Weinheimer C, Kovacs A, Courtois M, et al. Akt1 is required for physiological cardiac growth. Circulation. 2006;113:2097–2104. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muslin AJ, DeBosch B. Role of Akt in cardiac growth and metabolism. Novartis Found Symp. 2006;274:118–126. discussion 126–131, 152–115, 272–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cameron AJ, De Rycker M, Calleja V, Alcor D, Kjaer S, Kostelecky B, et al. Protein kinases, from B to C. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1013–1017. doi: 10.1042/BST0351013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milburn CC, Deak M, Kelly SM, Price NC, Alessi DR, Van Aalten DM. Binding of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate to the pleckstrin homology domain of protein kinase B induces a conformational change. Biochem J. 2003;375:531–538. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guertin DA, Stevens DM, Thoreen CC, Burds AA, Kalaany NY, Moffat J, et al. Ablation in mice of the mTORC components raptor, rictor, or mLST8 reveals that mTORC2 is required for signaling to Akt-FOXO and PKC[alpha], but Not S6K1. Dev Cell. 2006;11:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Der Heide LP, Hoekman MF, Smidt MP. The ins and outs of FoxO shuttling: mechanisms of FoxO translocation and transcriptional regulation. Biochem J. 2004;380:297–309. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oudit GY, Penninger JM. Cardiac regulation by phosphoinositide 3-kinases and PTEN. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82:250–260. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujio Y, Nguyen T, Wencker D, Kitsis RN, Walsh K. Akt promotes survival of cardiomyocytes in vitro and protects against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mouse heart. Circulation. 2000;101:660–667. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.6.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miao W, Luo Z, Kitsis RN, Walsh K. Intracoronary, adenovirus-mediated Akt gene transfer in heart limits infarct size following ischemia-reperfusion injury in vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:2397–2402. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsujita Y, Muraski J, Shiraishi I, Kato T, Kajstura J, Anversa P, et al. Nuclear targeting of Akt antagonizes aspects of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11946–11951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsui T, Li L, del Monte F, Fukui Y, Franke TF, Hajjar RJ, et al. Adenoviral gene transfer of activated phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase and Akt inhibits apoptosis of hypoxic cardiomyocytes in vitro. Circulation. 1999;100:2373–2379. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.23.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricci C, Jong CJ, Schaffer SW. Proapoptotic and antiapoptotic effects of hyperglycemia: role of insulin signaling. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;86:166–172. doi: 10.1139/Y08-021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Negoro S, Oh H, Tone E, Kunisada K, Fujio Y, Walsh K, et al. Glycoprotein 130 regulates cardiac myocyte survival in doxorubicin-induced apoptosis through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt phosphorylation and Bcl-xL/caspase-3 interaction. Circulation. 2001;103:555–561. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiraishi I, Melendez J, Ahn Y, Skavdahl M, Murphy E, Welch S, et al. Nuclear targeting of Akt enhances kinase activity and survival of cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2004;94:884–891. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000124394.01180.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gude N, Muraski J, Rubio M, Kajstura J, Schaefer E, Anversa P, et al. Akt promotes increased cardiomyocyte cycling and expansion of the cardiac progenitor cell population. Circ Res. 2006;99:381–388. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000236754.21499.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shioi T, McMullen JR, Kang PM, Douglas PS, Obata T, Franke TF, et al. Akt/protein kinase B promotes organ growth in transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2799–2809. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2799-2809.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsui T, Li L, Wu JC, Cook SA, Nagoshi T, Picard MH, et al. Phenotypic spectrum caused by transgenic overexpression of activated Akt in the heart. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22896–22901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biggs WH, 3rd, Meisenhelder J, Hunter T, Cavenee WK, Arden KC. Protein kinase B/Akt-mediated phosphorylation promotes nuclear exclusion of the winged helix transcription factor FKHR1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7421–7426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kops GJ, de Ruiter ND, De Vries-Smits AM, Powell DR, Bos JL, Burgering BM. Direct control of the Forkhead transcription factor AFX by protein kinase B. Nature. 1999;398:630–634. doi: 10.1038/19328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du K, Montminy M. CREB is a regulatory target for the protein kinase Akt/PKB. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32377–32379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rota M, Boni A, Urbanek K, Padin-Iruegas ME, Kajstura TJ, Fiore G, et al. Nuclear targeting of Akt enhances ventricular function and myocyte contractility. Circ Res. 2005;97:1332–1341. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000196568.11624.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. New directions for protecting the heart against ischaemia-reperfusion injury: targeting the Reperfusion Injury Salvage Kinase (RISK)-pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:448–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai HC, Liu TJ, Ting CT, Sharma PM, Wang PH. Insulin-like growth factor-1 prevents loss of electrochemical gradient in cardiac muscle mitochondria via activation of PI 3 kinase/Akt pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;205:99–106. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMullen JR, Shioi T, Huang WY, Zhang L, Tarnavski O, Bisping E, et al. The insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor induces physiological heart growth via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase(p110alpha) pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4782–4793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Eickels M, Grohe C, Cleutjens JP, Janssen BJ, Wellens HJ, Doevendans PA. 17beta-estradiol attenuates the development of pressure-overload hypertrophy. Circulation. 2001;104:1419–1423. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.095577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patten RD, Karas RH. Estrogen replacement and cardiomyocyte protection. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu CH, Liu JY, Wu JP, Hsieh YH, Liu CJ, Hwang JM, et al. 17beta-estradiol reduces cardiac hypertrophy mediated through the up-regulation of PI3K/Akt and the suppression of calcineurin/NF-AT3 signaling pathways in rats. Life Sci. 2005;78:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Condorelli G, Drusco A, Stassi G, Bellacosa A, Roncarati R, Iaccarino G, et al. Akt induces enhanced myocardial contractility and cell size in vivo in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12333–12338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172376399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taniyama Y, Ito M, Sato K, Kuester C, Veit K, Tremp G, et al. Akt3 overexpression in the heart results in progression from adaptive to maladaptive hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schiekofer S, Shiojima I, Sato K, Galasso G, Oshima Y, Walsh K. Microarray analysis of Akt1 activation in transgenic mouse hearts reveals transcript expression profiles associated with compensatory hypertrophy and failure. Physiol Genomics. 2006;27:156–170. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00234.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samarel AM. IGF-1 overexpression rescues the failing heart. Circ Res. 2002;90:631–633. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000015425.11187.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camper-Kirby D, Welch S, Walker A, Shiraishi I, Setchell KD, Schaefer E, et al. Myocardial Akt activation and gender: increased nuclear activity in females versus males. Circ Res. 2001;88:1020–1027. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.090858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugden PH, Clerk A. Akt like a woman: gender differences in susceptibility to cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2001;88:975–977. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.091864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kato T, Muraski J, Chen Y, Tsujita Y, Wall J, Glembotski CC, et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide promotes cardiomyocyte survival by cGMP-dependent nuclear accumulation of zyxin and Akt. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2716–2730. doi: 10.1172/JCI24280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Catalucci D, Condorelli G. Effects of Akt on cardiac myocytes: location counts. Circ Res. 2006;99:339–341. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000239409.90634.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sussman M. ‘Akt’ing lessons for stem cells: regulation of cardiac myocyte and progenitor cell proliferation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2007;17:235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muraski JA, Rota M, Misao Y, Fransioli J, Cottage C, Gude N, et al. Pim-1 regulates cardiomyocyte survival downstream of Akt. Nat Med. 2007;13:1467–1475. doi: 10.1038/nm1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang R, Brattain MG. Akt can be activated in the nucleus. Cell Signal. 2006;18:1722–1731. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saji M, Vasko V, Kada F, Allbritton EH, Burman KD, Ringel MD. Akt1 contains a functional leucine-rich nuclear export sequence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pekarsky Y, Koval A, Hallas C, Bichi R, Tresini M, Malstrom S, et al. Tcl1 enhances Akt kinase activity and mediates its nuclear translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3028–3033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040557697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koh H, Jee K, Lee B, Kim J, Kim D, Yun YH, et al. Cloning and characterization of a nuclear S6 kinase, S6 kinase-related kinase (SRK); a novel nuclear target of Akt. Oncogene. 1999;18:5115–5119. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takaishi H, Konishi H, Matsuzaki H, Ono Y, Shirai Y, Saito N, et al. Regulation of nuclear translocation of forkhead transcription factor AFX by protein kinase B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11836–11841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.del Peso L, Gonzalez VM, Hernandez R, Barr FG, Nunez G. Regulation of the forkhead transcription factor FKHR, but not the PAX3-FKHR fusion protein, by the serine/threonine kinase Akt. Oncogene. 1999;18:7328–7333. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brownawell AM, Kops GJ, Macara IG, Burgering BM. Inhibition of nuclear import by protein kinase B (Akt) regulates the subcellular distribution and activity of the forkhead transcription factor AFX. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3534–3546. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3534-3546.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Altiok S, Batt D, Altiok N, Papautsky A, Downward J, Roberts TM, et al. Heregulin induces phosphorylation of BRCA1 through phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32274–32278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hinton CV, Fitzgerald LD, Thompson ME. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling enhances nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of BRCA1. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:1735–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou BP, Liao Y, Xia W, Spohn B, Lee MH, Hung MC. Cytoplasmic localization of p21Cip1/WAF1 by Akt-induced phosphorylation in HER-2/neu-overexpressing cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:245–252. doi: 10.1038/35060032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rossig L, Jadidi AS, Urbich C, Badorff C, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Akt-dependent phosphorylation of p21(Cip1) regulates PCNA binding and proliferation of endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5644–5657. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.16.5644-5657.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shin I, Yakes FM, Rojo F, Shin NY, Bakin AV, Baselga J, et al. PKB/Akt mediates cell-cycle progression by phosphorylation of p27(Kip1) at threonine 157 and modulation of its cellular localization. Nat Med. 2002;8:1145–1152. doi: 10.1038/nm759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liang J, Zubovitz J, Petrocelli T, Kotchetkov R, Connor MK, Han K, et al. PKB/Akt phosphorylates p27, impairs nuclear import of p27 and opposes p27-mediated G1 arrest. Nat Med. 2002;8:1153–1160. doi: 10.1038/nm761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Viglietto G, Motti ML, Bruni P, Melillo RM, D’Alessio A, Califano D, et al. Cytoplasmic relocalization and inhibition of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27(Kip1) by PKB/Akt-mediated phosphorylation in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2002;8:1136–1144. doi: 10.1038/nm762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shin I, Rotty J, Wu FY, Arteaga CL. Phosphorylation of p27Kip1 at Thr-157 interferes with its association with importin alpha during G1 and prevents nuclear re-entry. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6055–6063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412367200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim J, Jonasch E, Alexander A, Short JD, Cai S, Wen S, et al. Cytoplasmic sequestration of p27 via Akt phosphorylation in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:81–90. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mayo LD, Donner DB. A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway promotes translocation of Mdm2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11598–11603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181181198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ashcroft M, Ludwig RL, Woods DB, Copeland TD, Weber HO, MacRae EJ, et al. Phosphorylation of HDM2 by Akt. Oncogene. 2002;21:1955–1962. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Basu S, Totty NF, Irwin MS, Sudol M, Downward J. Akt phosphorylates the Yes-associated protein, YAP, to induce interaction with 14–3-3 and attenuation of p73-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2003;11:11–23. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00776-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baldin V, Theis-Febvre N, Benne C, Froment C, Cazales M, Burlet-Schiltz O, et al. PKB/Akt phosphorylates the CDC25B phosphatase and regulates its intracellular localisation. Biol Cell. 2003;95:547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katayama K, Fujita N, Tsuruo T. Akt/protein kinase B-dependent phosphorylation and inactivation of WEE1Hu promote cell cycle progression at G2/M transition. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5725–5737. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5725-5737.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gervais M, Dugourd C, Muller L, Ardidie C, Canton B, Loviconi L, et al. Akt down-regulates ERK1/2 nuclear localization and angiotensin II-induced cell proliferation through PEA-15. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:3940–3951. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosner M, Freilinger A, Hengstschlager M. Akt regulates nuclear/cytoplasmic localization of tuberin. Oncogene. 2007;26:521–531. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.York B, Lou D, Noonan DJ. Tuberin nuclear localization can be regulated by phosphorylation of its carboxyl terminus. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:885–897. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rosner M, Hengstschlager M. Cytoplasmic/nuclear localization of tuberin in different cell lines. Amino Acids. 2007;33:575–579. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rosner M, Freilinger A, Hanneder M, Fujita N, Lubec G, Tsuruo T, et al. p27Kip1 localization depends on the tumor suppressor protein tuberin. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1541–1556. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ferrigno P, Silver PA. Regulated nuclear localization of stress-responsive factors: how the nuclear trafficking of protein kinases and transcription factors contributes to cell survival. Oncogene. 1999;18:6129–6134. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou BP, Hung MC. Novel targets of Akt, p21(Cipl/WAF1), and MDM2. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:62–70. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.34057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Muraski JA, Fischer KM, Wu W, Cottage CT, Quijada P, Mason M, et al. Pim-1 kinase antagonizes aspects of myocardial hypertrophy and compensation to pathological pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13889–13894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Matsuda T, Zhai P, Maejima Y, Hong C, Gao S, Tian B, et al. Distinct roles of GSK-3alpha and GSK-3beta phosphorylation in the heart under pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20900–20905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808315106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Antos CL, McKinsey TA, Frey N, Kutschke W, McAnally J, Shelton JM, et al. Activated glycogen synthase-3 beta suppresses cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:907–912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231619298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haq S, Choukroun G, Kang ZB, Ranu H, Matsui T, Rosenzweig A, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta is a negative regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:117–130. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Basso AD, Solit DB, Chiosis G, Giri B, Tsichlis P, Rosen N. Akt forms an intracellular complex with heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) and Cdc37 and is destabilized by inhibitors of Hsp90 function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39858–39866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Solit DB, Basso AD, Olshen AB, Scher HI, Rosen N. Inhibition of heat shock protein 90 function down-regulates Akt kinase and sensitizes tumors to Taxol. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2139–2144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wu R, Kausar H, Johnson P, Montoya-Durango DE, Merchant M, Rane MJ. Hsp27 regulates Akt activation and polymorphonuclear leukocyte apoptosis by scaffolding MK2 to Akt signal complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21598–21608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fan GC, Zhou X, Wang X, Song G, Qian J, Nicolaou P, et al. Heat shock protein 20 interacting with phosphorylated Akt reduces doxorubicin-triggered oxidative stress and cardiotoxicity. Circ Res. 2008;103:1270–1279. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakamura T, Inoue K, Ogawa S, Umehara H, Ogonuki N, Miki H, et al. Effects of Akt signaling on nuclear reprogramming. Genes Cell. 2008;13:1269–1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reed JC. Proapoptotic multidomain Bcl-2/Bax-family proteins: mechanisms, physiological roles, and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1378–1386. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ye K, Ahn JY. Nuclear phosphoinositide signaling. Front Biosci. 2008;13:540–548. doi: 10.2741/2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim SJ. Insulin rapidly induces nuclear translocation of PI3-kinase in HepG2 cells. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1998;46:187–196. doi: 10.1080/15216549800203692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lu PJ, Hsu AL, Wang DS, Yan HY, Yin HL, Chen CS. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase in rat liver nuclei. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5738–5745. doi: 10.1021/bi972551g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martelli AM, Borgatti P, Bortul R, Manfredini M, Massari L, Capitani S, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase translocates to the nucleus of osteoblast-like MC3T3-E1 cells in response to insulin-like growth factor I and platelet-derived growth factor but not to the proapoptotic cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1716–1730. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.9.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Metjian A, Roll RL, Ma AD, Abrams CS. Agonists cause nuclear translocation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gamma. A Gbetagamma-dependent pathway that requires the p110gamma amino terminus. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27943–27947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ye K. PIKE GTPase-mediated nuclear signalings promote cell survival. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:570–576. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ye K, Hurt KJ, Wu FY, Fang M, Luo HR, Hong JJ, et al. Pike. A nuclear gtpase that enhances PI3kinase activity and is regulated by protein 4.1N. Cell. 2000;103:919–930. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ye K, Snyder SH. PIKE GTPase: a novel mediator of phosphoinositide signaling. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:155–161. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Deleris P, Bacqueville D, Gayral S, Carrez L, Salles JP, Perret B, et al. SHIP-2 and PTEN are expressed and active in vascular smooth muscle cell nuclei, but only SHIP-2 is associated with nuclear speckles. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38884–38891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lindsay Y, McCoull D, Davidson L, Leslie NR, Fairservice A, Gray A, et al. Localization of agonist-sensitive PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 reveals a nuclear pool that is insensitive to PTEN expression. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:5160–5168. doi: 10.1242/jcs.000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tanaka K, Horiguchi K, Yoshida T, Takeda M, Fujisawa H, Takeuchi K, et al. Evidence that a phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-binding protein can function in nucleus. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3919–3922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ahn JY, Liu X, Cheng D, Peng J, Chan PK, Wade PA, et al. Nucleophosmin/B23, a nuclear PI(3,4,5)P(3) receptor, mediates the antiapoptotic actions of NGF by inhibiting CAD. Mol Cell. 2005;18:435–445. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lee SB, Xuan Nguyen TL, Choi JW, Lee KH, Cho SW, Liu Z, et al. Nuclear Akt interacts with B23/NPM and protects it from proteolytic cleavage, enhancing cell survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16584–16589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807668105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gillooly DJ, Morrow IC, Lindsay M, Gould R, Bryant NJ, Gaullier JM, et al. Localization of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate in yeast and mammalian cells. EMBO J. 2000;19:4577–4588. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Irvine RF. Nuclear lipid signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:349–360. doi: 10.1038/nrm1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Martelli AM, Tabellini G, Borgatti P, Bortul R, Capitani S, Neri LM. Nuclear lipids: new functions for old molecules? J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Neri LM, Milani D, Bertolaso L, Stroscio M, Bertagnolo V, Capitani S. Nuclear translocation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in rat pheochromocytoma PC 12 cells after treatment with nerve growth factor. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 1994;40:619–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lim MA, Kikani CK, Wick MJ, Dong LQ. Nuclear translocation of 3′-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK-1): a potential regulatory mechanism for PDK-1 function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14006–14011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335486100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Andjelkovic M, Alessi DR, Meier R, Fernandez A, Lamb NJ, Frech M, et al. Role of translocation in the activation and function of protein kinase B. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31515–31524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zini N, Ognibene A, Bavelloni A, Santi S, Sabatelli P, Baldini N, et al. Cytoplasmic and nuclear localization sites of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in human osteosarcoma sensitive and multidrug-resistant Saos-2 cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 1996;106:457–464. doi: 10.1007/BF02473307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sano T, Lin H, Chen X, Langford LA, Koul D, Bondy ML, et al. Differential expression of MMAC/PTEN in glioblastoma multiforme: relationship to localization and prognosis. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1820–1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Scheid MP, Parsons M, Woodgett JR. Phosphoinositide-dependent phosphorylation of PDK1 regulates nuclear translocation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2347–2363. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2347-2363.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Adini I, Rabinovitz I, Sun JF, Prendergast GC, Benjamin LE. RhoB controls Akt trafficking and stage-specific survival of endothelial cells during vascular development. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2721–2732. doi: 10.1101/gad.1134603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhu L, Hu C, Li J, Xue P, He X, Ge C, et al. Real-time imaging nuclear translocation of Akt1 in HCC cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;356:1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Webster KA. Aktion in the nucleus. Circ Res. 2004;94:856–859. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126699.49835.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rubio MAD, Fischer K, Emmanuel GE, Gude N, Miyamoto S, Mishra S, et al. Cardioprotective stimuli mediate phosphoinosotide 3-kinase and phosphoinositide dependent kinase 1 nuclear accumulation in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.02.022. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Walsh K. Akt signaling and growth of the heart. Circulation. 2006;113:2032–2034. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.615138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bullock AN, Debreczeni J, Amos AL, Knapp S, Turk BE. Structure and substrate specificity of the Pim-1 kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41675–41682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510711200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hoover D, Friedmann M, Reeves R, Magnuson NS. Recombinant human pim-1 protein exhibits serine/threonine kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14018–14023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bachmann M, Hennemann H, Xing PX, Hoffmann I, Moroy T. The oncogenic serine/threonine kinase Pim-1 phosphorylates and inhibits the activity of Cdc25C-associated kinase 1 (C-TAK1): a novel role for Pim-1 at the G2/M cell cycle checkpoint. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48319–48328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Roh M, Gary B, Song C, Said-Al-Naief N, Tousson A, Kraft A, et al. Overexpression of the oncogenic kinase Pim-1 leads to genomic instability. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8079–8084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kim KT, Baird K, Ahn JY, Meltzer P, Lilly M, Levis M, et al. Pim-1 is up-regulated by constitutively activated FLT3 and plays a role in FLT3-mediated cell survival. Blood. 2005;105:1759–1767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lilly M, Sandholm J, Cooper JJ, Koskinen PJ, Kraft A. The PIM-1 serine kinase prolongs survival and inhibits apoptosis-related mitochondrial dysfunction in part through a bcl-2-dependent pathway. Oncogene. 1999;18:4022–4031. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]