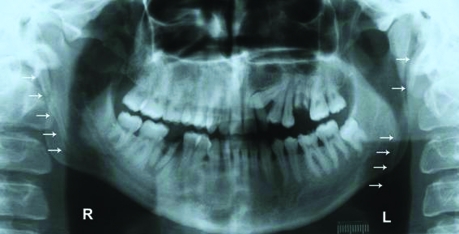

A 26-year-old man who had end-stage renal disease (ESRD) due to primary glomerulonephritis presented for a routine dental examination. He had peritoneal dialysis (PD) as renal replacement therapy for 2 years. He had smoking one to two packs of cigarettes a day for five years and did not drink alcohol. On clinical examination, the maxillary left canine tooth was absent. The left first molar tooth’s clinical crown was fully carious, but its roots were in the jaw. In the mandibular jaw, the right first molar tooth and the left first molar tooth were carious. A panoramic radiography (PR) was taken as a screening film after the examination. Radiographic imaging showed that the left canine tooth was impacted, and the left first molar tooth’s roots were in the maxillary jaw. In the mandibular jaw, the left third molar tooth was also impacted and the right first molar tooth was carious, but the roots were in the jaw. Bilateral styloid process elongations (SPEs) were also detected (right: 47 mm, left: 58 mm) in the PR of the patient (Figure 1). He had any complaints regarding SPE or Eagle’s syndrome.

Figure 1.

Bileteral styloid process elongation in an end-stage renal disease patient with peritoneal dialysis on a panoramic radiography.

The styloid process (SP) is a cylindrical, long cartilaginous bone located on the temporal bone. There are many vessels such as carotid arteries and nerves adjacent to the SP.1,2 The normal length of the SP is approximately 20–30 mm.3–8 The length of SP and/or stylohyoid ligament, which are longer than 30 mm were considered to be SPE.3,5,7–10 SPE resulted in facial and neck pain is known as Eagle’s syndrome.5,6,10,11 More uncommonly, symptoms such as dysphagia, tinnitus, and otalgia may occur in patients with this syndrome. The symptoms and signs with this syndrome are due to the anatomic relationship between the SP and its surrounding structures.1,12 Therefore, it may also cause stroke due to the compression of carotid arteries.3,13

The exact cause of the elongated SP due to calcified and ossified bone and the ligament is not clear. It was suggested that local chronic irritations, surgical trauma, endocrine disorders in female at menopause, persistence of mesenchymal elements, growth of the osseous tissue and mechanical stress or trauma during development of SP could result in calcified hyperplasia of the SP.3,10,14,15

Extraskeletal (ectopic) calcification or ossification may have a role for the elongation of the SP. Ectopic calcification (EC) in nonosseous soft tissue may be due to three mechanisms: metastatic calcification due to disorders causing abnormal serum Ca and P levels, dystrophic calcification due to mineral deposition into metabolically impaired or dead tissue despite normal serum levels of Ca and P, and ectopic ossification. The patients with ESRD have risks for EC due to disorders (renal failure, dialysis, secondary hyperparathyroidism) causing metastatic calcification.16 In the present report, a detailed differential diagnosis was done for the disorders causing dystrophic calcification (scleroderma, dermatomyositis, systemic lupus erythematosis, trauma-induced etc.), ectopic ossification (post surgery, burns, neurologic injury, myositis ossificans etc.) and also, any diseases causing metastatic calcification. Except renal failure, disease causing metastatic calcification such as sarcoidosis, tumoral calcinosis, primary hyperparathyroidism, milk alkali syndrome etc. were investigated for this patient and any disease was detected.16

As a result, SPE found as incidental findings on PRs may be important clinically in not only patients with ESRD, but also normal population. Instead of many hypotheses and studies, the exact etiology of elongated SP and the role of ectopic calcification are unknown. Abnormality in Ca and P metabolism (EC) is very common in patients with ESRD. According to our knowledge, this is the first case study showing SPE associated with ESRD in a patient. In conclusion, this report suggests that EC or the abnormality in Ca and P metabolism may have a role in the elongation of SP. However, further studies and large samples are needed to clarify the etiology of this disorder, and the role of EC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gözil R, Yener N, Calgüner E, Araç M, Tunç E, Bahcelioḡlu M. Morphological characteristics of styloid process evaluated by computerized axial tomography. Ann Anat. 2001;183:527–535. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(01)80060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camarda AJ, Deschamps C, Forest D., II Stylohyoid chain ossification: a discussion of etiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:515–520. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prasad KC, Kamath MP, Reddy KJ, Raju K, Agarwal S. Elongated styloid process (Eagle’s syndrome): a clinical study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:171–175. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.29814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monsour PA, Young WG. Variability of the styloid process and stylohyoid ligament in panoramic radiographs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61:522–526. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ilguy M, Ilguy D, Guler N, Bayirli G. Incidence of the type and calcification patterns in patients with elongated styloid process. J Int Med Res. 2005;33:96–102. doi: 10.1177/147323000503300110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kursoglu P, Unalan F, Erdem T. Radiological evaluation of the styloid process in young adults resident in Turkey’s Yeditepe University faculty of dentistry. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Oral Endod. 2005;100:491–494. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung T, Tschernitschek H, Hippen H, Schneider B, Borchers L. Elongated styloid process: when is it really elongated? Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004;33:119–124. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/13491574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaki HS, Greco CM, Rudy TE, Kubinski JA. Elongated styloid process in a temporomandibular disorder sample: prevalence and treatment outcome. J Prosthet Dent. 1996;75:399–405. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(96)90032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keur JJ, Campbell JP, McCarthy JF, Ralph WJ. The clinical significance of the elongated styloid process. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61:399–404. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murtagh RD, Caracciolo JT, Fernandez G. CT findings associated with Eagle syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1401–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eagle WW. Elongated styloid process. Report of two cases. Arch Otolaryngol. 1937;25:548–587. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1949.03760110046003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bafaqeeh SA. Eagle syndrome: classic and carotid artery types. J Otolaryngol. 2000;29:88–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chuang WC, Short JH, McKinney AM, Anker L, Knoll B, McKinney ZJ. Reversible left hemispheric ischemia secondary to carotid compression in Eagle syndrome: surgical and CT angiographic correlation. Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:143–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balbuena L, Jr, Hayes D, Ramirez SG, Johnson R. Eagle’s syndrome (elongated styloid process) South Med J. 1997;90:331–334. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199703000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fini G, Gasparini G, Filippini F, Becelli R, Marcotullio D. The long styloid process syndrome or Eagle’s syndrome. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2000;28:123–127. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2000.0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Favus MJ, Vokes TJ. Paget disease and other dysplasias of bone. In: Jameson JL, editor. Harrison’s endocrinology. USA: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2006. pp. 485–498. [Google Scholar]