Abstract

More than a decade has passed since the conclusion of the Minnesota tobacco trial and the signing of the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) by 46 US State Attorneys General and the US tobacco industry. The Minnesota settlement exposed the tobacco industry's long history of deceptive marketing, advertising, and research and ultimately forced the industry to change its business practices. The provisions for public document disclosure that were included in the Minnesota settlement and the MSA have resulted in the release of approximately 70 million pages of documents and nearly 20,000 other media materials. No comparable dynamic, voluminous, and contemporaneous document archive exists. Only a few single events in the history of public health have had as dramatic an effect on tobacco control as the public release of the tobacco industry's previously secret internal documents. This review highlights the genesis of the release of these documents, the history of the document depositories created by the Minnesota settlement, the scientific and policy output based on the documents, and the use of the documents in furthering global public health strategies.

BAT = British American Tobacco; FCTC = Framework Convention on Tobacco Control; JAMA = Journal of the American Medical Association; LTDL = Legacy Tobacco Documents Library; MSA = Master Settlement Agreement; NCI = National Cancer Institute; PMI = Philip Morris International; RICO = Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations; TobReg = Study Group on Tobacco Control Regulation; TTC = transnational tobacco company; UCSF = University of California, San Francisco; WHO = World Health Organization

More than a decade has passed since Minnesota settled its litigation against the tobacco industry. The Minnesota settlement has been recognized as one of the most important public health events of the second half of the 20th century because it exposed the tobacco industry's long history of deceptive marketing, advertising, and research.1 It has also been more than 10 years since the tobacco industry's individual settlements with the states of Mississippi (1997), Florida (1997), and Texas (1998) and since the signing of the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) between 46 US State Attorneys General and the tobacco companies (1998). These agreements are the 5 largest settlements in the history of litigation.2

Before the Minnesota tobacco case, filed in 1994 by the Minnesota Attorney General and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Minnesota, successful litigation against the cigarette manufacturers had been almost universally unsuccessful. The “first wave” of suits from the 1950s to the 1970s were met by an industry that had adopted a “scorched earth” litigation strategy, outspending individual litigants by orders of magnitude while vehemently denying any association between their product and diseases such as lung cancer.2 Through hundreds of cases between 1950 and 1970, the tobacco industry disclosed only a few thousand internal documents, thereby maintaining an impregnable wall of silence.3 The first crack in this wall occurred during the “second wave” of tobacco litigation; this wave was marked by the 1983 Cipollone case, in which plaintiffs aggressively sought and received a small cache of damning documents.4

Other events converged in the mid-1990s to expose the tobacco industry's wrongdoing. In 1994, copies of internal documents from the Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation were leaked and were ultimately published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 1995.5 Although these documents were not numerous (4000 pages), they were selected because of their damning content and were sent anonymously to Stanton A. Glantz, PhD, a widely recognized tobacco control researcher. These documents became the basis not only for the articles in JAMA but also for the book The Cigarette Papers.6 The publication of this book was a historic event and provided the deepest look inside the tobacco industry before the Minnesota litigation. In 1994, the US Food and Drug Administration, under the leadership of then-director David A. Kessler, MD, sought to regulate tobacco products by claiming not only that these products were drug delivery devices but also that the industry controlled and manipulated the form and quantity of nicotine contained within their products.7 In addition, Jeffrey Wigand, PhD, a former vice president at Brown & Williamson, began to cooperate with the Food and Drug Administration and ultimately told his story on the television program 60 Minutes.8 The industry was further exposed in Congressional hearings chaired by Representative Henry Waxman (Democrat, California), during which chief executives were forever immortalized on videotape as they swore before Congress and the American people that nicotine was not addictive.9 All of these events were damaging to the tobacco industry, but even collectively their legacy does not compare with that of the Minnesota tobacco trial, which changed the tobacco control landscape forever.

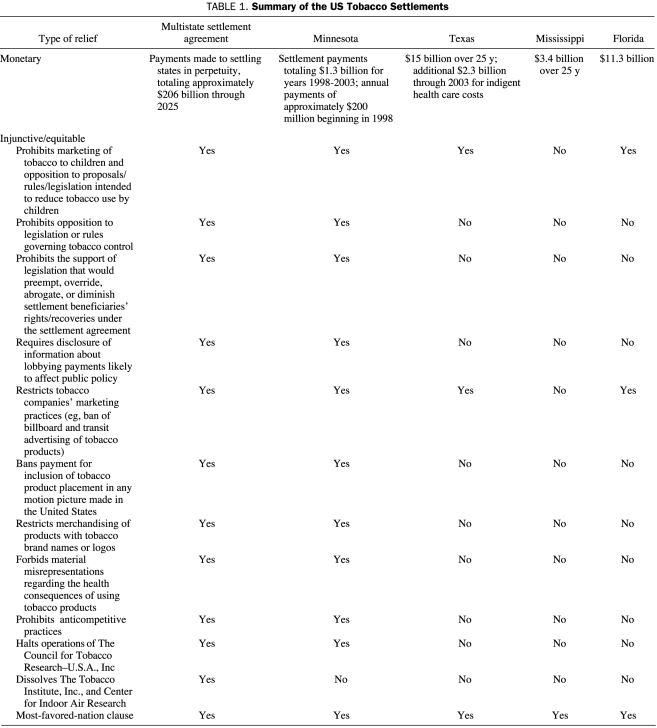

Although the terms of the massive tobacco settlements included large monetary awards and unprecedented public health relief (Table 1), the legacy of the Minnesota trial is the public disclosure of millions of pages of previously secret internal documents from the tobacco industry and the continued disclosure of such documents produced during discovery in US smoking and health litigation from 1998 to 2008. For the first time in history, the Minnesota settlement also allowed public access to the files of UK tobacco giant British American Tobacco (BAT). The MSA also required large tobacco companies to maintain their letter-sized records on the Internet and to deposit any oversized or electronic media in Minnesota until June 2010. To date, these legal settlements have resulted in the release of approximately 70 million pages of documents, thousands of audiovisual files, and hundreds of other electronic media files. No other comparable dynamic, voluminous, and contemporaneous document archive exists. We would argue that the use of these documents in furthering public health goals based in science, policy, and litigation—the 3 fronts on which the tobacco industry had successfully escaped accountability for decades—has been nothing short of astounding.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the US Tobacco Settlements

The first peer-reviewed article based on tobacco companies' internal documents introduced during the Minnesota trial by the plaintiffs' witnesses was published 10 years ago in JAMA.10 The article and the authors' testimony focused on nicotine addiction, pH manipulation, and low-tar/low-nicotine cigarettes. Since then, several hundred peer-reviewed articles have been published. We summarize the multiple legacies of the Minnesota trial and the MSA by highlighting the effect that these internal documents from the tobacco industry have had on tobacco control around the world.

CREATING “SKELETONS” IN THE CLOSET: THE DOCUMENT DEPOSITORIES

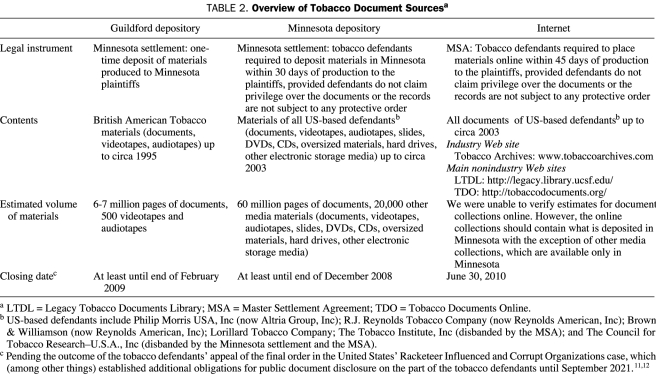

The terms of the Minnesota settlement provided for the creation of 2 publicly accessible document depositories: one in Minneapolis, MN (Minnesota depository) and the other in Guildford, England, near London (Guildford depository) (Table 2). The Minnesota depository contains materials from all defendants, whereas the Guildford depository contains only materials produced to the Minnesota plaintiffs from the defendant BAT.13 At their sole expense, the settling tobacco industry defendants were obligated by the Minnesota settlement to allow public access to the litigation depositories for 10 years.13 After the Guildford depository had been open to the public for only a year, BAT's public relations firm reported to the company that its depository was a “skeleton” in the company's closet,14 in part because of the public airing of its internal documents relating to cigarette smuggling, price fixing, control of scientific research by attorneys, and political attacks against the World Health Organization (WHO).15

TABLE 2.

Overview of Tobacco Document Sourcesa

When the depositories were opened to the public in May 1998 (Minnesota) and February 1999 (Guildford), approximately 35 million pages of once-secret internal documents were available for public review.3 Since the settlement in 1998, the number of pages of tobacco industry documents available for public review has nearly doubled because (1) the Minnesota settlement mandated that all of defendants' previously unproduced documents in any US civil smoking and health litigation during the following 10 years be placed into the Minnesota depository13 and (2) the MSA required the settling tobacco defendants to place oversized and electronic media into the Minnesota depository.16 In one case alone, the US Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) case against the tobacco industry, United States v Philip Morris USA, Inc., et al, the tobacco defendants were forced to produce an additional 26 million pages of documents.17

The Minnesota depository currently houses approximately 60 million pages, and the Guildford depository, approximately 6 to 7 million pages. The Minnesota settlement, in combination with the terms of the MSA, has also made publicly available approximately 20,000 other media materials (audiotapes, videotapes, CDs, DVDs, slides, maps, oversized paper materials, microfilm, and external storage devices such as hard drives). Before the Minnesota litigation, US tobacco companies had produced only a relatively small number of documents during several decades of litigation, and BAT had never produced a single document in a smoking and health action.3

For decades, the tobacco industry had engaged in “scorched earth” litigation tactics aimed at building a nearly impregnable wall around the industry. Included in the industry's litigation tactics were abuses of the attorney-client privilege doctrine as a means of keeping scientific documents secret.3 In Minnesota, the industry faced a brilliant legal team representing the State and a wise, no-nonsense veteran judge who held both sides accountable. In fact, we think that the courageous rulings of the judge, the Honorable Kenneth J. Fitzpatrick, resulted in revelations about this industry that no one could have anticipated.18 Viewed in this context, the sheer volume and breadth of the documents and electronic media available for public review as a result of the Minnesota settlement and the MSA are staggering.

Although the Minnesota litigation resulted in previously unimaginable access to millions of tobacco industry records, substantial barriers have prevented public access to the depositories' contents during the past 10 years. Although the Minnesota depository was administered by an independent third-party paralegal firm,19 BAT was allowed to manage the daily operations of the Guildford depository.20 In doing so, the company violated the spirit of the Minnesota settlement, a fact documented by both the legislative and judicial branches of government and by journalists and academicians.15,17,21-24 Operations at the Minnesota depository were also affected by BAT's conduct with respect to its obligations to make certain litigation documents publicly available. In 2006, Mayo Clinic sought legal relief for its research team from BAT's interference with document research conducted at the Minnesota depository. Mayo sought to compel BAT to produce documents that Mayo thought BAT was obligated to produce into the depository in accordance with the Minnesota settlement and to order BAT to cease interfering with Mayo investigators' use of and access to documents.25 The court did not address the merits of Mayo's claim because it held that Mayo, which was not a party to the Minnesota litigation, did not have legal standing to enforce the Minnesota settlement.26 Although the 10-year public access provision of the Minnesota settlement was an ingenious instrument for furthering the discovery of revelations regarding the industry's behavior, users of the depositories have ultimately been unable to seek relief from disruptions to research and issues related to document access at the depositories.27

Now that 10 years have passed, whether the depositories will close as stated in the Minnesota settlement or will remain open with the addition of new documents is unclear. The Minnesota settlement provided that the Minnesota depository would be in operation for 10 years from May 8, 1998,13 and that the Guildford depository would be maintained for a period of 10 years after its opening on February 22, 1999.13 Accordingly, the Minnesota depository was set to close on May 8, 2008, and the Guildford depository, on February 22, 2009. However, the final order in the RICO case against the tobacco industry requires that the defendants maintain the Minnesota and Guildford Depositories until September 2021.11 Were that decision to be upheld, it would enforce the disclosure of contemporary documents about the tobacco industry's activity, especially because the “light” cigarette case ruling by the Supreme Court of the United States will undoubtedly result in the filing of new litigation against the industry. The tobacco defendants have appealed the case; oral arguments were heard by the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in October 2008.12 A decision is expected in early 2009.

DIGITIZING THE DOCUMENTS

Tobacco Defendants Based in the United States

Although the Minnesota settlement required the tobacco defendants to deposit their hard-copy documents in depositories, the MSA obligated the settling tobacco parties to make their documents available online until June 30, 2010.28 In effect, most of the documents produced by US-based defendants and placed into the Minnesota depository have also been posted on industry-created Web sites, with the exception of oversized and electronic materials that the MSA requires to be deposited in Minnesota.16

The tobacco industry's Web sites, developed under the MSA,29 were initially perhaps easier to search than were the hard-copy documents at the depositories30; however, these electronic files have proved to be difficult to use because of impaired search functions, inconsistencies between the tobacco entities' Web sites, and inaccessibility to images. Furthermore, tobacco industry Web sites allow their managers to track user searches.27 In response to the limited search capability of tobacco industry sites, the research community sought to make tobacco document images more accessible and useable and to create permanent images on the Internet. After the MSA required the settling tobacco defendants to provide the National Association of Attorneys General with a “snapshot” of each of their Web sites in July 1999,29 the images were available to the research community, which devised other means of enhancing document access.

Computer programs called spiders have been used to identify images and indexing information on the tobacco defendants' Web sites. These programs allow the ongoing collection of documents as defendants add new documents to their Web sites in response to litigation. Beginning in 1999, Tobacco Documents Online (http://tobaccodocuments.org/) standardized the available document descriptions to allow for uniform searching and offered previously unavailable and invaluable searching tools such as full-text searching (made possible by optical character recognition, or OCR, which converts images into text) and the ability to systematically collect and annotate documents.31 Before the availability of Tobacco Documents Online's enhanced search tools, researchers could not conduct full-text searches and instead had to rely on the indexed fields that were coded for each document (eg, author, title, date).

Similarly, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Library, which had already been posting internal documents from the tobacco industry on the Web,32 began offering researchers more user-friendly options for searching the documents than those provided by the industry sites. In 2002, UCSF, supported by a $10-million grant from the American Legacy Foundation, launched the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library (LTDL), which allows comprehensive, user-friendly, full-text searching. In addition to offering enhanced searching tools, LTDL will remain a permanent online collection.33 Additional collections of tobacco company documents are also available online.34,35

British American Tobacco

Because BAT was not a party to the MSA's requirement of online production of documents, digitizing the documents produced by BAT has been challenging.15 After almost 8 years of efforts by researchers and staff from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Mayo Clinic, and UCSF, with expenditures of $3.6 million, 6 to 7 million pages of BAT documents from both depositories were digitized and made publicly accessible at LTDL.36 Although the expenditures for document acquisition and accessibility by the public health community have been substantial, they pale in comparison to what the tobacco industry has probably spent on operations aimed at managing internal documents. For example, at the time of the Minnesota litigation, one of the tobacco defendants alone, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, disclosed to the Minnesota plaintiffs' lawyers that it had spent $90 million to create its document index.37

INFLUENCE OF THE TOBACCO DOCUMENTS

The response of the tobacco control community to the release of the documents has been profound. However, comprehensive document research would not have occurred without the availability of mechanisms for researching and disseminating the findings from the documents on their public release in Minnesota.

Faced with a treasure trove of documents previously hidden from public view but in an inaccessible format, in 1998 US President Bill Clinton issued an executive memorandum mandating that the Department of Health and Human Services address the issue of how to make the documents more accessible and how to expose relevant content.38,39 The Department turned to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), which issued a Request For Proposals from the scientific community.40 Since 1999, NCI's initiative has resulted in 17 peer-reviewed research grants with a total expenditure of $23.2 million (Michele Bloch, MD, PhD, Medical Officer, Tobacco Control Research Branch, Behavioral Research Program, NCI, written communication, June 2008).

During the past 10 years, more than 500 publications (453 peer-reviewed journal articles, 32 books or book chapters, and 51 reports) relating to the tobacco documents41 have been published across diverse disciplines. The topics of these publications can be categorized as follows: industry science and ethics, secondhand smoke, industry strategy and tactics, ingredients and product design, litigation, marketing, regional issues, economics, youth-related activities, and document research and commentary.41 Examples from nearly every aspect of the tobacco industry's operations have been reported. Publicity surrounding these publications has undoubtedly influenced public opinion about the unscrupulous behavior of the tobacco industry and has furthered health policy goals, in part by denormalizing smoking as an acceptable behavior and discrediting the tobacco industry as a stakeholder in health policy.42,43 In addition to academic publications, the release of the tobacco documents has generated several seminal public health reports from the WHO and its regional offices2,44-46 and from civil society organizations.47,48

Although the impact of the Minnesota litigation has seemingly been centered in the United States, acknowledgment of its impact on tobacco control throughout the world is growing. There is general agreement that many of the advances in tobacco control during the past 10 years have their roots in Minnesota. Although public disclosure of tobacco documents is a creation of US litigation, many tobacco industry defendants are transnational companies. Consequently, the public release of the documents has had a global impact. The release of correspondence between parent companies and foreign subsidiaries has allowed a glimpse into the operations of transnational tobacco companies (TTCs). Accordingly, tobacco control advocates, researchers, and litigants working outside the United States have made extensive use of the documents to support their own health policy efforts.

Although the following is not a comprehensive accounting of the extraordinary efforts of the global tobacco control community, we offer a few examples of individuals and organizations that have used the documents to effect health policy change outside the United States. In 2007, Pascal A. Diethelm, president of the Swiss antismoking group OxyRomandie and vice president of the National Committee Against Smoking, France was given the 2007 International Tobacco Industry Document Research and Advocacy Award for using the documents to reveal the consulting relationship between Philip Morris International (PMI) and a researcher at the University of Geneva, Ragnar Rylander.49 Rylander did not disclose his ties to the tobacco industry in his publications on secondhand smoke. Once this became known through the documents, the University rebuked him and also adopted a policy of no longer allowing its scientists to accept tobacco industry funding. In the statement announcing this policy, the University noted that “The huge mass of tobacco industry documents that has been made public as a result of judgements pronounced by American tribunals against this industry shows that these companies have attempted to manipulate public opinion for decades, and that the targeted recruitment of a large number of scientists has been a privileged instrument of this disinformation plot.” In Nigeria, Akinbode Oluwafemi, on behalf of Environmental Rights Action/Friends of the Earth Nigeria, searched and used the documents to support the April 2007 lawsuit filed by the Lagos State Government in conjunction with Environmental Rights Action seeking legal relief from the industry's efforts to target young people.50 In Finland, Heikki Hilamo has used the documents to produce extensive peer-reviewed publications and books in English and Finnish on topics such as product liability and industry interference with tobacco control.41 In 2003, Professor Gérard Dubois51 of France published a landmark document exposing the tobacco industry's playbook.

The use of documents by individuals and organizations working to effect policy in their own countries has also occurred in Brazil,52 Indonesia,53 and Austria.54 Furthermore, civil society organizations have used the documents in advocacy efforts to combat the tobacco industry's influence across the globe.47,55-57 Researchers from approximately 70 countries have published regional tobacco document analyses.58 Efforts from the $500-million multipronged tobacco control campaign, which is funded by New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg59 and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation60 and which focuses on reducing the prevalence of smoking in low- and middle-income countries, have relied on revelations from tobacco documents. For example, the global tobacco control campaign funded by the Bloomberg Initiative (WHO's MPOWER package [monitor tobacco use and prevention policies; protect people from tobacco smoke; offer help to quit tobacco use; warn about the dangers of tobacco; enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship; and raise taxes on tobacco]) highlights documents produced to Minnesota plaintiffs and addresses the importance of revealing tobacco industry tactics.61 Had it not been for the Minnesota litigation and the subsequent release of documents, only a small fraction of these events would have taken place in the past decade.

TOBACCO DOCUMENTS AND THE WHO

Document disclosures resulting from the Minnesota litigation have had an extraordinary influence on the global regulation of the TTCs under the leadership of the WHO. In the late 1990s, former WHO Director General Gro Harlem Brundtland launched a landmark inquiry into the tobacco industry's efforts to undermine global tobacco control, as evidenced by tobacco documents made public in Minnesota.44 The 2000 WHO expert report concluded:

At the most fundamental level, this inquiry confirms that tobacco use is unlike other threats to global health. Infectious diseases do not employ multinational public relations firms. There are no front groups to promote the spread of cholera. Mosquitoes have no lobbyists. The evidence presented here suggests that tobacco is a case unto itself, and that reversing its burden on global health will be not only about understanding addiction and curing disease, but, just as importantly, about overcoming a determined and powerful industry.44

The WHO's regional offices also directed substantial resources into mining the tobacco documents that were made public in Minnesota.58

In direct response to the WHO inquiry, the 54th World Health Assembly (WHA) passed resolution WHA54.18 Transparency in Tobacco Control62 in 2001. This resolution urges WHO member states to monitor and to inform its membership about industry affiliations with its membership, as well as to communicate information about identified efforts of the industry to subvert health policy.62 As stated by the WHO, the documents were instrumental in developing the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC)63:

The tobacco industry made a big strategic mistake in Minnesota that is reverberating around the world….[The Minnesota plaintiffs'] plan was to bury the industry in its own documents by forcing disclosure of the truth about what the industry knew, when they knew it, and what they did to hide the truth from the public. The Minnesota team doggedly pursued the industry documents (including several trips to the US Supreme Court) and eventually forced the industry to turn over the material Minnesota needed to make its case….Today, the WHO Tobacco Free Initiative is using these documents to help develop the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control as well as national tobacco control efforts around the world. They are an invaluable resource and probably the most important and lasting result of the tobacco litigation in the United States. The truth will set us all free.64 [Emphasis added]

WHO's comprehensive findings, based on its inspection of the tobacco documents, have proved invaluable in FCTC treaty negotiations. The disclosed documents could be shared with policy makers to inform them of the tobacco industry's efforts to circumvent health policies and to assist them in removing the industry as a stakeholder in the ratification process. Furthermore, in spite of the interference of the tobacco industry in the development of the FCTC,65 several FCTC articles (Article 5.3, 12.C, and 20.4C) are designed to protect tobacco control initiatives from the tobacco industry's decades-long mission of subverting and obfuscating public health measures.63

Finally, to date, 161 countries are Parties to the FCTC. Several guidelines, which are aimed at assisting Parties in meeting their obligations under the treaty, have thus far been developed. As of this writing, the Conference of the Parties has adopted strong guidelines in Article 5.3 (protection of public health policy with respect to tobacco control from the commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry), Article 8 (protection from exposure to tobacco smoke), Article 11 (packaging and labeling), and Article 13 (advertising, promotion, and sponsorship).

Former Director General Brundtland also made the regulation of tobacco production a high priority for WHO by appointing the Scientific Advisory Committee on Tobacco Product Regulation. This committee was subsequently elevated to the status of a standing committee and in 2003 was renamed the WHO Study Group on Tobacco Control Regulation (TobReg). With its prominent status as a standing committee, the WHO TobReg is positioned to develop meaningful standards for tobacco product regulation around the world well into the future. These standards will have a substantial impact in developing countries that lack the expertise and resources to develop their own standards. Many TobReg members have been associated with the tobacco documents, including Channing Robertson, PhD, who was the second witness in the Minnesota trial. The TobReg issued its report, The Scientific Basis of Tobacco Product Regulation, in 2007.66

TOBACCO DOCUMENTS IN LEGISLATIVE AND PARLIAMENTARY INVESTIGATIONS

The internal documents of the tobacco industry have also been used in parliamentary and legislative hearings. In July 1999, the UK House of Commons Health Select Committee24 reviewed documents made public by the Minnesota settlement, set forth nearly 60 recommendations for reducing the health burden of tobacco use, and urged the government to act on its recommendations.24 In the United States, tobacco documents have informed policy makers about the TTCs' internal strategies regarding “reduced-risk” products. In the 2003 congressional investigation of “reduced-risk” tobacco products, documents produced to the Minnesota depository disclosed correspondence from a senior tobacco company researcher who opined that the technology did not and will not exist to manufacture a “reduced-risk” product (a cigarette low in tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines), even while members of the tobacco industry were simultaneously touting the potential health benefit of such products.67

LITIGATION

The publicly available internal corporate records of tobacco companies are also a valuable resource for litigation efforts. In particular, Minnesota's document discovery allowed access by every litigant in cases brought after the Minnesota settlement to 35 million pages of internal records and thousands of documents stripped of privilege by the Minnesota court through its application of the crime-fraud exception to the doctrine of privilege.37 The importance of the Minnesota settlement has been so great that a description of the landscape of global tobacco control has suggested that, “quite simply, ‘when the history of tobacco … is written, there is going to be before the Minnesota case and after the Minnesota case.’”68

The US case against the tobacco industry was extremely document-intensive, as noted by the court,62 and may be “the largest piece of civil litigation ever brought.”69 In United States v Philip Morris, the government proved its case.70 However, a 2005 decision of a Scottish court, McTear v Imperial Tobacco Ltd, determined that the defendant tobacco company was not liable for the death of the plaintiff (who had smoked 2 packs per day) from lung cancer and that “there was no scientific proof of causation between the plaintiff's smoking and his death from lung cancer.”71 The plaintiff in McTear was denied legal aid and, as a result, lacked the financial resources that may have allowed her access in court to the sort of documents available to the plaintiffs in the Minnesota and RICO cases.71 This contemporaneous example makes apparent the importance of plaintiffs' access to documents such as those made public by the Minnesota settlement. However, it should be pointed out that disclosure laws differ from one country to the next; for example, these laws are more restrictive in the United Kingdom and less restrictive in the United States. This is one aspect of the US legal system that makes litigation a far more powerful regulatory tool for promoting product safety than it may be in other countries.43 Furthermore, the cost of failed suits in the United Kingdom falls to the plaintiff; this regulation discourages plaintiffs who are less well financed, even when they have a strong case.

Nonetheless, the documents have had, and probably will continue to have, a great impact on tobacco-regulation litigation throughout the world, as predicted by commentators after the initial release of these documents.72 Within 2 years after the 1998 US tobacco settlements, tobacco litigation of some type had been filed in Australia, Bangladesh, Brazil, Canada, China, Finland, France, Germany, India, Ireland, Israel, Japan, the Marshall Islands, Norway, Oman, Pakistan, Peru, Poland, South Korea, Spain, Sri Lanka, Switzerland, Uganda, and the United Kingdom.2 Currently, many cases are pending in countries other than the United States. In Brazil, for example, a case filed against PMI in 1995, The Smoker Health Defense Association (ADESF) v Souza Cruz, S.A. and Philip Morris Marketing, S.A., was decided for the plaintiffs, but the appeal was pending as of December 2008.70 The government of British Columbia brought suit against PMI in 2001, seeking recovery of past and future costs associated with a “tobacco related wrong.”73 The trial in that case, British Columbia v Imperial Tobacco Ltd., et al, is set to begin in September 2010.73 In 2007, the Nigerian government filed a lawsuit for recovery of health care costs against BAT, PMI, and others, seeking US $22.9 billion in damages for costs incurred by treating their citizens for tobacco-related illnesses.74 According to media coverage of the case:

A lot of their case is based on documents found at the British American Tobacco Documents Archives. BAT was required to make their internal documents public after a lawsuit won by the American state of Minnesota. Now many of these documents are for public use online, maintained by the University of California, San Francisco, Mayo Clinic and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. In this archive there are documents in which BAT reveals that they were aware of the fact that few Nigerians know the health risks of cigarette smoking and, in fact, many Nigerians believe that smoking may even be healthy.50

Litigation against tobacco manufacturers is also currently pending in Israel, Spain, Columbia, Nigeria, Argentina, and Turkey.73

A final example of the influence of the tobacco documents released under the Minnesota settlement on other litigation is the recent 5-to-4 ruling by the US Supreme Court in Altria Group, Inc. v Good, which allows filings against tobacco manufacturers of cases that allege deceptive marketing of “light” and “low-tar” cigarettes.75 The topic of “low-tar” or “light” cigarettes was central to the testimony of 1 of the authors of the current review (R.D.H.), and the industry's knowledge of the false health claims made about these products had not been previously entered into the public record. Had most members of the US Supreme Court agreed with the industry, the case would have ended the approximately 40 pending “light” cigarette cases and could have barred future cases involving deceptive health-related claims of any kind. As noted by legal scholars, “even the state lawsuits that resulted in the $246 billion Master Settlement Agreement 10 years ago would arguably have been barred” if the industry had prevailed at the Supreme Court.76

UNANTICIPATED DOCUMENT FINDINGS

Although a primary goal of the Minnesota litigation was “to expose the industry's decades-long campaign of deception by revealing the industry's secret research in smoking and health, addiction and nicotine manipulation,”77 the documents revealed much more than the industry anticipated. The tobacco defendants' plan to overwhelm the Minnesota plaintiffs with truckloads of documents back-fired, as reported by the WHO:

The idea—what lawyers call “papering”—was to simply bury the relevant material in a lot of trash. They forgot that winters are long in Minnesota and did not realize that the Minnesota team would look through all the paper….And while 99.9% of the material that the industry produced in Minnesota was irrelevant to the Minnesota trial, it had great relevance to other tobacco control issues…. Indeed, the documents reveal industry subversion of not only the scientific but also the political process all over the world.63,64

Documents released in Minnesota expanded public knowledge of information that had not been previously available to the public in existing sources. First, the documents, through reports published by journalists, researchers, and civil society organizations, paved the way for holding the companies accountable for their role in the global illicit tobacco trade and provided information that has proved crucial to the development of effective counterstrategies against this trade.48,78-88 In 2008, for example, Canada's largest cigarette manufacturers pleaded guilty to aiding and abetting tobacco smuggling and agreed to pay CanD$1.15 billion for defrauding the Canadian government of unpaid taxes. Also, in a different case, without admitting guilt and in return for dropping smuggling-related litigation against Philip Morris, the company agreed to pay US $1.25 billion to the European Commission, the executive branch of the European Union.89 Article 15 of the WHO FCTC, the world's first public health treaty, makes provisions for measures aimed at combating the illicit tobacco trade. Parties to the FCTC are currently negotiating a supplementary treaty aimed at ending this practice.65

A second area highlighted by the Minnesota settlement was the extent to which lawyers concealed and destroyed documents. Although before the Minnesota case went to trial there had been glimpses of what the tobacco industry had been hiding in its files,5,6,90-96 after more than 20 trial court orders and more than 5 appeals Minnesota's successful application of the crime-fraud exception to the attorney-client privilege and work-product doctrine resulted in the release of an additional 39,000 explosive documents.39 These most secret documents, previously protected by attorney-client privilege, provided evidence of the industry's systematic destruction and concealment of information, including abuses of the attorney-client privilege doctrine.97,98 The judge in United States v Philip Morris, et al, the Honorable Gladys Kessler, who found the major tobacco companies guilty of violating certain provisions of the RICO statute in August 2006,99 summarized the tobacco industry's conduct related to suppression of information:

The evidence is clear that on a significant number of occasions, Defendants did in fact suppress research and destroy documents to protect themselves and the industry….By destroying evidence, Defendants make it virtually impossible to know what materials existed prior to their destruction.100

Finally, in September 2008, the UK's Royal College of Physicians called for an end to smoking in the United Kingdom in 20 years, a call that would have been unfathomable just 10 years earlier.101

CONCLUSION

Few single events in the history of public health have had as dramatic an effect on global tobacco control as the public release of the tobacco industry's internal documents in the Minnesota tobacco trial and through the MSA. The tobacco industry's own words have reverberated through court rooms, public hearings, and media outlets across the globe, and this decade of truth has forever affected health policy worldwide. In fact, one of the legacies of the tobacco documents may be the end of cigarettes as a prevalent and legal commodity.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 CA90791, “Tobacco Industry Documents on Environmental Tobacco Smoke-The Next Front” from the National Cancer Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weinstein H. Big tobacco settles Minnesota lawsuit for $6.6 billion. Los Angeles Times May9, 1998: A1. Statement made by C. Everett Koop, Former U.S. Surgeon General http://articles.latimes.com/1998/may/09/news/mn-47882 Accessed February 19, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Towards Health With Justice: Litigation and Public Inquiries as Tools for Tobacco Control Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. http://www.who.int/tobacco/en/final_jordan_report.pdf Accessed February 19, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciresi MV, Walburn RB, Sutton TD. Decades of deceit: document discovery in the Minnesota tobacco litigation. William Mitchell Law Rev. 1999;25:477-566 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douglas CE, Davis RM, Beasley JK. Epidemiology of the third wave of tobacco litigation in the United States, 1994-2005. Tob Control 2006;15(suppl IV):iv9-iv16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glantz SA, Barnes DE, Bero L, Hanauer P, Slade J. Looking through a keyhole at the tobacco industry: the Brown and Williamson documents. JAMA 1995;274(3):219-224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glantz SA, Slade J, Bero LA, Hanauer P, Barnes DE. The Cigarette Papers Berkley, CA: University of California Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/dailys/02/Sep02/090602/800253a7.pdf. Nicotine in cigarettes and smokeless tobacco is a drug and these products are nicotine delivery devices under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act: Jurisdictional Determination, 61 Fed Reg 44619-01 (Aug 28, 1996) Accessed February 20, 2009.

- 8.JeffreyWigand.com Web site. Jeffrey Wigand on 60 Minutes, February4, 1996. http://www.jeffreywigand.com/60minutes.php Accessed February 20, 2009

- 9.http://www.house.gov/waxman/issues/health/tobacco_leg.htm. Representative Henry Waxman Web site. Issues and Legislation: Tobacco. Accessed February 20, 2009.

- 10.Hurt RD, Robertson CR. Prying open the door to the cigarette industry's secrets about nicotine: the Minnesota Tobacco Trial. JAMA 1998;280(13):1173-1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United States v Philip Morris USA I, et al., 449 F Supp 2d 1 (D.D.C. 2006). appeal pending, No. 06-5267 (D.C. Cir.). Order # 1021. Filed September 20, 2006

- 12.Unites States v Philip Morris USA. No. 06-5267 (D.C. Cir. June 11, 2008) (order setting date of oral argument)

- 13.Consent Judgment. The State of Minnesota and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Minnesota v Philip Morris et al Court File No. C1-94-8565 May8, 1998. http://www.library.ucsf.edu/sites/all/files/ucsf_assets/mnconsent.pdf Accessed February 20, 2009

- 14.Legacy Tobacco Documents Library Web site Shandwick W. Presentation to BAT March22, 2000. British American Tobacco; Bates No. 325049984 http://bat.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wpm30a99 Accessed February 20, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muggli ME, LeGresley EM, Hurt RD. Big tobacco is watching: British American Tobacco's surveillance and information concealment at the Guildford Depository. Lancet 2004;363(9423):1812-1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Project Tobacco Web site Master Settlement Agreement Paragraph IV(g) November23, 1998. http://www.naag.org/backpages/naag/tobacco/msa/msa-pdf/1109185724_1032468605_cigmsa.pdf/file_view Accessed February 20, 2009

- 17.United States v Philip Morris USA I, et al. 449 F Supp 2d 1 (D.D.C. 2006). appeal pending, No. 06-5267 (D.C. Cir.)http://www.usdoj.gov/civil/cases/tobacco2/amended%20opinion.pdf Accessed February 20, 2009

- 18.Phelps D. Judge Kenneth Fitzpatrick: order in the court; unflappable jurist in spotlight as state, Blue Cross join in lawsuit against tobacco firms. Minneapolis Star Tribune January27, 1997:1D [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smart Legal Assistance 119 North 4th Street Minneapolis, MN 55104 Direct: (612) 340-1030. Fax: (612) 340-0019 Email: mndepo@aol.com http://www.tobaccoarchives.com/docbasic.html Accessed February 20, 2009

- 20.http://bat.library.ucsf.edu/ Guildford depository. Unit 3A, Opus Business Park Moorfield Road, Slyfield Guildford, GU1 1SZ. Tel: +44 (1483) 464 300. Requests for admission to the Guildford depository should be faxed to the BAT Legal Department: British American Tobacco. Globe House 4, Temple Place London, UK WC2R 2PG, Fax: 44 20 7845 2783. Accessed February 20, 2009.

- 21.Glantz S. The truth about big tobacco in its own words: it is time to truly open up British American Tobacco's depository in Guildford [editorial]. BMJ 2000;321(7257):313-314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collin J, Lee K, Gilmore AB. Unlocking the corporate documents of British American Tobacco: an invaluable global resource needs radically improved access. Lancet 2004;363(9423):1746-1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee K, Gilmore AB, Collin J. Looking inside the tobacco industry: revealing insights from the Guildford depository [editorial]. Addiction 2004;99(4):394-397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Select Committee on Health. House of Commons http://www.parliament.the-stationery-office.co.uk/pa/cm199900/cmselect/cmhealth/27/2702.htm. Health: Second Report. Smoking in Britain: awareness of the health risks of smoking. Session 1999-2000. Publications and Records Web site. Accessed: February 23, 2009.

- 25.Memorandum of Law of Support of the Mayo Clinic's Motion to Compel the Deposit of Documents by British American Tobacco Company and to Preclude its Interference with the Use of the Documents in the Minnesota Depository January17, 2006. The State of Minnesota and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Minnesota v Philip Morris et al. Court File No. C1-94-8565 http://stic.neu.edu/MN/court_orders/2134.min.html Accessed February 23, 2009

- 26.Order RE Tobacco Depository August18, 2006. The State of Minnesota and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Minnesota v Philip Morris et al. Court File No. C1-94-8565

- 27.Brief of Amicus Curiae in United States v Philip Morris USA I, et al. The Regents of the University of California in Support of the United States' Proposed Final Judgment and Order, August24, 2005. http://www.library.ucsf.edu/sites/all/files/ucsf_assets/amicus_curiae_ucsf.pdf Accessed February 23, 2009

- 28.Project Tobacco; National Association of Attorneys General Master settlement agreement. Paragraphs IV(c) and IV(d) November23, 1998. http://www.naag.org/backpages/naag/tobacco/msa/msa-pdf/1109185724_1032468605_cigmsa.pdf/file_view Accessed February 23, 2009

- 29.http://www.tobaccoarchives.com/ Tobacco Archives. com Web site. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 30.Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tob Control 2000;9(3):334-338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tobacco Documents Online TOBACCODOCUMENTS.org Web site. http://tobaccodocuments.org/about.php Accessed February 23, 2009

- 32.Authors' note. In June 1995, the UCSF Library posted thousands of Brown and Williamson documents, which the company sought, but failed, to have permanently removed. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. v Regents of the University of California (Super. Ct. for Country of San Francisco, No 967298)

- 33.University of California SF http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/ Legacy Tobacco Documents Library Web site. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 34.Roswell Park Cancer Institute http://roswell.tobaccodocuments.org/ Tobacco document and advertising collection. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 35.The Centre for Tobacco Control Research UK Tobacco industry advertising documents database Tobaccopapers.com Web site. http://tobaccopapers.com/ Accessed February 23, 2009

- 36.http://bat.library.ucsf.edu/history.html. British American Tobacco Documents Archive. The Guildford Archiving Project's (GAP) history. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 37.Walburn RB. The role of the once-confidential industry documents. William Mitchell Law Rev. 1999;25:431-438 [Google Scholar]

- 38.US Dept of Health and Human Services HHS unveils new tobacco industry documents Web site November18, 1999. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/1999pres/991118.html Accessed October 2008

- 39.White House fact sheet. President Clinton makes tobacco documents more accessible to the public July17, 1998. http://hhs.gov/news/press/1998pres/980716a.html Accessed October 2008

- 40.US Dept of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute Review and analysis of tobacco industry documents [announcement] Rockville, MD: Office of Extramural Research; June17, 1999. PAR-99-114 http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/par-99-114.html Accessed February 23, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 41.UCSF Library Web site http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docsbiblio. Tobacco Documents Bibliography. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 42.Bero L. Implications of the tobacco industry documents for public health and policy. Annu Rev Public Health 2003;24:267-288 Epub 2001 Nov 6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vernick JS, Rutkow L, Teret SP. Public health benefits of recent litigation against the tobacco industry. JAMA 2007;298(1):86-89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization http://www.who.int/tobacco/media/en/who_inquiry.pdf. Tobacco company strategies to undermine tobacco control activities at the World Health Organization: report of the committee of experts on tobacco industry documents: July 2000. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 45.Pan American Health Organization http://www.paho.org/English/HPP/HPM/TOH/profits_over_people.pdf. Profits over people: tobacco industry activities to market cigarettes and undermine public health in Latin America and the Caribbean: November 2002. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 46.World Health Organization EMRO. Voice of Truth: Multinational Tobacco Industry activity in the Middle East: A review of internal industry documents Available at: http://www.emro.who.int/TFI/VOICE%20OF%20TRUTH.pdf Accessed January 5, 2009

- 47.http://old.ash.org.uk/html/conduct/pdfs/bat2005.pdf. Action on Smoking and Health. Christian Aid; Friends of Earth. BAT in its own words. 2005 Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 48.http://tobaccofreekids.org/campaign/global/framework/docs/Smuggling.pdf. Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. Illegal pathways to illegal profits: the big cigarette companies and international smuggling. 2001 Apr; Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 49.Public Health Advocacy Institute http://www.tobaccodocumentaward.com/ International award for outstanding use of tobacco industry documents. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 50.Kubuitsile L. Tobacco firms find market in Third World [news release]. Mmegi Online Web site August27, 2007. Mmegi Online http://www.mmegi.bw/index.php?sid=1&aid=7&dir=2007/August/Wednesday22 Accessed February 23, 2009

- 51.Dubois G. Le Rideau de Fumée: Les méthodes secrètes de l'industrie du tabac Paris, France: Le Seuil; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Instituto Nacional De Cancer (INCA) www.inca.gov.br. Brasil- Advertencias Sanitarias nos Produtos de Tabaco- 2009. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 53.Tobacco firms target kids: probe. The Jakarta Post June14, 2007. http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2007/06/14/tobacco-firms-target-kids-probe.html Accessed February 23, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davani K, Busson S. http://www.smokereality.com/ Smoke Reality: Free Your Mind. 2007 Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 55.Corporate Accountability International http://www.stopcorporateabuse.org/cms/page1747.cfm. Challenging Abuse, Protecting People. Challenging Big Tobacco: Big Tobacco Surveillance Quotes. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 56.Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance; SEATCA. Accessed February 23, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Framework Convention Alliance http://fctc.org/ Working for a world free from death and disease caused by tobacco Web site. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 58.Authors' note For a complete and current list of peer-reviewed articles published from the tobacco documents relating to countries or regions outside of the U.S. see the Legacy Tobacco Document Library bibliography available at: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/smokebiblio Accessed February 23, 2009

- 59.Frieden TR, Bloomberg MR. How to prevent 100 million deaths from tobacco. Lancet 2007;369(9574):1758-1761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McNeil DG. Billionaires back antismoking effort. The New York Times July24, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/24/health/24tobacco.html Accessed February 23, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 61.World Health Organization http://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/en/ WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008 - The MPOWER package. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 62.World Health Organization http://www.who.int/tobacco/framework/wha_eb/wha54_18/en/index.html. WHA 54.18 Transparency in tobacco control. Published May 22, 2001. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 63.World Health Organization http://www.who.int/tobacco/framework/WHO_FCTC_english.pdf. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 64.World Health Organization http://www.who.int/tobacco/policy/industry_conduct/en/print.html. Industry Conduct. Accessed April 9, 2009.

- 65.Saloojee Y, Dagli E. Tobacco industry tactics for resisting public health policy on health. Bull World Health Organ 2000;78(7):902-910 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.eScholarship Repository. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education The Scientific Basis of Tobacco Product Regulation: Report of a WHO Study Group Tobacco Control. WHO Tobacco Control Papers Paper WHOTSR2007 January1, 2007. http://repositories.cdlib.org/tc/whotcp/WHOTSR2007 Accessed February 23, 2009

- 67.Committee on Government Reform. US House of Representatives http://oversight.house.gov/documents/20040629082458-34684.pdf. The lessons of “light” and “low tar” cigarettes: without effective regulation, “reduced risk” tobacco products threaten the public health. Published June 3, 2003. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 68.Dolan M. The Minnesota tobacco case—Reasoned antitrust analysis goes up in smoke: State By Humphrey v Philip Morris Inc., 551 N.W.2d 490 (Minn. 1996). Hamline Law Rev. 2002;193:194-195 [Google Scholar]

- 69.United States v Philip Morris USA I, et al. No. 99-2496 http://www.usdoj.gov/civil/cases/tobacco2/amended%20opinion.pdf Accessed February 23, 2009

- 70.Philip Morris International http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1413329/000119312508229203/d10q.htm. Form 10Q, filed December 2008. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 71.Friedman L, Daynard R. Scottish court dismisses a historic smoker's suit. Tob Control 2007;16(5):e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pedersen L. Tobacco Litigation Worldwide: Follow Up Study to Norwegian Official Report 2000: 6 “Tort Liability for the Norwegian Tobacco Industry.” Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Agency for Health and Social Welfare; 2002. http://www.shdir.no/vp/multimedia/archive/00001/is-1004_1701a.pdf Accessed February 23, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Philip Morris International http://www.phillipmorrisinternational.com. Form 10-12B/A, Ex. 99.2, filed March 5, 2008. Accessed April 9, 2009.

- 74.Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids International Resource Center http://www.tobaccofreecenter.org/nigeria_lawsuit12nov07. Nigerian advocates take on big tobacco: groups battle tax waivers, take to the airwaves. Published November 12, 2007. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 75.http://www.supremecourtus.gov/opinions/08pdf/07-562.pdf. Altria Group, Inc. et al. v Good, et al. No. 07-562. (2008) Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 76.Tobacco Control Legal Consortium http://tobaccolawcenter.org/documents/legal-update-fall-2008.pdf. Legal update: Supreme Court up-holds smokers rights to sue. 2008 Fall; Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 77.Czajkowski A. The making of a lawsuit: a health plan perspective. William Mitchell Law Rev. 1999;25:382 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Legresley E, Lee K, Muggli ME, Patel P, Collin J, Hurt RD. British American Tobacco and the “insidious impact of illicit trade” in cigarettes across Africa. Tob Control 2008;17(5):339-346 Epub 2008 Jul 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.http://www.ash.org.uk/files/documents/ASH_567.pdf. BAT and tobacco smuggling-evidence to the Health Select Committee. Tobacco industry smuggling: Submission to the House of Commons Health Select Committee. Action on Smoking and Health 16th February 2000. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 80.International Consortium of Investigative Journalists Tobacco companies linked to criminal organizations in lucrative cigarette smuggling, China March3, 2001. Washington DC: Center for Public Integrity; http://projects.publicintegrity.org/Content.aspx?context=article&id=351 Accessed March 22, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Collin J, Legresley E, MacKenzie R, Lawrence S, Lee K. Complicity in contraband: British American Tobacco and cigarette smuggling in Asia. Tob Control 2004;13(suppl 2):ii104-ii111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee K, Collin J. ‘Key to the future’: British American Tobacco and cigarette smuggling in China. PLoS Med. 2006;3(7):e279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Joosens L, Raw M. Cigarette smuggling in Europe: who really benefits? Tob Control 1998;7(1):66-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gilmore AB, McKee M. Moving east: how the transnational tobacco industry gained entry to the emerging markets of the former Soviet Union, Part I: establishing cigarette imports. Tob Control 2004;13(2):143-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Joosens L, Raw M. http://old.ash.org.uk/luk/lukdocs/turningoffthetap.pdf. Turning off the tap: an update on cigarette smuggling in the UK and Sweden, with recommendations to control smuggling. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 86.World Health Organization The cigarette “transit” road to the Islamic Republic of Iran and Iraq. illicit tobacco trade in the Middle East Cairo, Egypt: WHO_EM/TFI/011/E/G/07.03/1000) http://www.emro.who.int/tfi/TFIiraniraq.pdf Accessed February 23, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 87.International Consortium of Investigative Journalists Tobacco companies linked to criminal organizations in cigarette smuggling, Africa Washington DC: Center for Public Integrity, 2001. http://www.project.publicintegrity.org/Content.aspx?context=article&id=351 Accessed March 22, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 88.Campbell D. Further evidence by Duncan Campbell in respect of smuggling in Africa by British American Tobacco PLC, obstruction of access to evidence. House of Commons TB51A Health Committee: Session 1999-2000 Inquiry into the Tobacco Industry and the Health Risks of Smoking. London: Published January 15, 2000. Accessed February 23, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marsden W. How to get away with smuggling: Canada's billion-dollar deal for big tobacco October19, 2008. Center for Public Integrity Web site http://www.publicintegrity.org/investigations/tobacco/articles/entry/765/ Accessed February 23, 2009

- 90.Orey M. Assuming the Risk: The Mavericks, The Lawyers and the Whistle-Blowers Who Beat Big Tobacco New York, NY: Little, Brown & Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hilts PJ. Smoke Screen: The Truth Behind the Tobacco Industry Cover Up Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publication Company, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kessler D. A Question of Intent: A Great American Battle With a Deadly Industry New York, NY: Public Affairs; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 93.UCSF Legacy Tobacco Documents Library About the collections http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/about/about_collections.jsp#ucbw and http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/ Accessed February 23, 2009

- 94.Barnes DE, Hanauer P, Slade J, Bero LA, Glantz SA. Environmental tobacco smoke: the Brown and Williamson documents. JAMA 1995;274(3):248-253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hanauer P, Slade J, Barnes DE, Bero L, Glantz SA. Lawyer control of internal scientific research to protect against products liability lawsuits: the Brown and Williamson documents. JAMA 1995;274(3):234-240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Collishaw NE. http://www.smoke-free.ca/pdf_1/MONTMINNnov1.pdf. Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada. From Montreal to Minnesota: following the trail of Imperial Tobacco's documents. Published September 1999. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 97.Guardino S, Friedman LC, Daynard RA. Remedies for document destruction: tales from the tobacco wars. Va J Soc Policy Law 2004;12:1-60 [Google Scholar]

- 98.LeGresley EM, Muggli ME, Hurt RD. Playing hide-and-seek with the tobacco industry. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(1):27-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act. 18 U S C § (1962) (c)(d)

- 100.http://www.usdoj.gov/civil/cases/tobacco2/amended%20opinion.pdf. Amended Final Opinion. United States of America v Philip Morris USA Inc, et al, case No. 99-CV-02496 (GK) at paragraph 3864, p 1408. Accessed February 23, 2009.

- 101.Royal College of Physicians http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/news/news.asp?pr_id=416. End tobacco smoking by 2025 [news] Ending tobacco smoking in Britain: radical strategies for prevention and harm reduction in nicotine addiction. Published September 8, 2008. Accessed February 23, 2009.