Abstract

Background and objectives: Patient knowledge about chronic hemodialysis (CHD) is important for effective self-management behaviors, but little is known about its association with vascular access use.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: Prospective cohort of adult incident CHD patients from May 2002 until November 2005 and followed for 6 mo after initiation of hemodialysis (HD). Patient knowledge was measured using the Chronic Hemodialysis Knowledge Survey (CHeKS). The primary outcome was dialysis access type at: baseline, 3 mo, and 6 mo after HD initiation. Secondary outcomes included anemia, nutritional, and mineral laboratory measures.

Results: In 490 patients, the median (interquartile range) CHeKS score (0 to 100%) was 65%[52% to 78%]. Lower scores were associated with older age, fewer years of education, and nonwhite race. Patients with CHeKS scores 20 percentage points higher were more likely to use an arteriovenous fistula or graft compared with a catheter at HD initiation and 6 mo after adjustment for age, sex, race, education, and diabetes mellitus. No statistically significant associations were found between knowledge and laboratory outcome measures, except for a moderate association with serum albumin. Potential limitations include residual confounding and an underpowered study to determine associations with some clinical measures.

Conclusions: Patients with less dialysis knowledge may be less likely to use an arteriovenous access for dialysis at initiation and after starting hemodialysis. Additional studies are needed to explore the impact of patient dialysis knowledge, and its improvement after educational interventions, on vascular access in hemodialysis.

Dialysis access is a critical part of the care of chronic hemodialysis (CHD) patients. Lower mortality has been associated with use of an arteriovenous fistula (AVF) or graft (AVG) compared with use of a catheter (1–3), and mortality risk is lowered if patients change from using a catheter to an AVF or AVG (4). Although fistula use has been increasing, in 2004 only 41% of prevalent CHD patients were using an AVF and another 35% used an AVG for dialysis access (5). Importantly, a large proportion of patients used a catheter for dialysis access. This high prevalence of catheter use is aggravated by the more than 80% of CHD patients who use a dialysis catheter for their first outpatient dialysis treatment (5).

Increasing access-related patient education has been suggested as a fundamental process to improve AVF use (6), and patient education is recommended by the National Kidney Foundation's Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF-KDOQI) and the American Nephrology Nurses’ Association to encourage patient empowerment and improve clinical outcomes (7,8). Both CHD patients and providers report that ongoing patient education is a top priority for comprehensive dialysis care (9–11).

Patient education has been associated with improved outcomes in complex chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and congestive heart failure (12–15). Improvement in patient knowledge has frequently been described as a primary outcome in randomized clinical trials evaluating kidney disease patient education (16). However, only a few small studies have demonstrated that higher knowledge in dialysis patients is associated with adherence to dialysis prescription and dietary recommendations (17,18), improved phosphorus management (19,20), control of comorbid disease (21), and better self-reported mental function (22). Little is known about the relationship between patient knowledge and vascular access at the time of, and the period following, maintenance hemodialysis initiation.

We measured patient knowledge of hemodialysis care as part of a multidisciplinary disease- management education program for incident CHD patients (23). The primary objective of this study is to describe patient hemodialysis knowledge, characteristics of patients with lower knowledge, and associations between knowledge and vascular access use in incident CHD patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

The RightStart (RS) program prospectively enrolled 901 incident adult CHD patients within two weeks after the initiation of outpatient dialysis from 38 participating clinics across the United States. Enrollment occurred from May 2002 until November 2005. Inclusion criteria were all CHD patients who were age 18 yr or greater and received hemodialysis therapy at a participating clinic for the study period. Exclusion criteria included seasonal or transient patients and those with poor cognitive function, as judged by the staff of the RS program, with the majority being nursing home residents. From within this cohort, all patients who had an assessment of dialysis care knowledge at the time of enrollment and documentation about type of access used at dialysis initiation were included in this study.

The Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University Medical Center approved this as an exempted study.

Knowledge Measurement

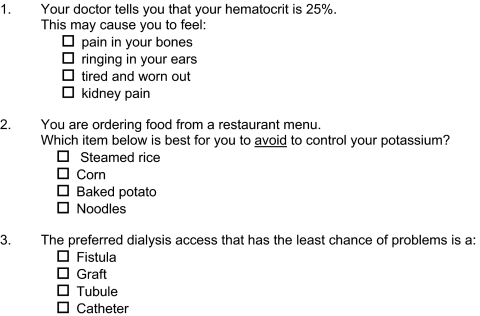

The Chronic Hemodialysis Knowledge Survey (CHeKS) was developed to evaluate patient knowledge about important issues in CHD care including dialysis adequacy, nutrition, anemia, access care, medications, and safety. Item content was determined by multidisciplinary experts of hemodialysis care including nephrologists, dialysis nurses, social workers, renal dietitians, and CHD patients. The scale included 23 multiple-choice items, with only one correct response (Figure 1) (see Supplemental Appendix for complete survey). The scores were reported as percent correct with a possible range of 0% to 100% with each item contributing equally. The readability of the survey by the Flesch Reading Ease score was 65.4 and the Flesh-Kincaid Grade Level was 5.8 (Microsoft Office, version 2003; Microsoft, Redmond, Washington). Administration of the survey without time limitations was performed by either the unit case management or trained research staff.

Figure 1.

CHeKS Question Examples.

Data Collection

Participant demographic information was collected from the electronic medical record. The primary clinical outcome, access type used, and secondary clinical measures including hematocrit, serum albumin, phosphorus, transferrin saturation, and intact-parathyroid hormone were collected from the medical record at baseline, 3 mo, and 6 mo after dialysis initiation.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of patient characteristics and CHeKS scores were performed and presented as either median (interquartile range) or proportion of the total patient population. Knowledge survey responsiveness was assessed in patients who completed the CHeKS both at baseline and 3 mo after dialysis initiation by comparing the two scores with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired observations. Internal consistency of the survey was determined by the Kuder-Richardson coefficient (KR-20) of reliability = 0.79 (24), a measure of reliability similar to the Cronbach's alpha used for scales with dichotomous responses. Using principal components factor analysis, we identified only one factor, or domain, for the CHeKS survey. The Eigen value was equal to 3.4 and this factor explained greater than 83% of the variance of the survey. Therefore, none of the 23 items was omitted from the knowledge test. Construct validity of the CHeKS survey was assessed by evaluation of an a priori model of correlation, hypothesizing that younger age (25,26), more years of education (27), and lower baseline serum phosphorus (20) would be moderately associated with higher knowledge scores.

Baseline CHeKS scores were evaluated for associations with clinical measures both as raw values and also categorized as either meeting or not meeting common goals described in the K/DOQI guidelines for hemodialysis quality measures (28). Associations were evaluated with Spearman's χ2 or Wilcoxon-rank sum test, as appropriate. Additionally, associations between use of an AVF or AVG and CHeKS score were determined by using the Cuzick nonparametric test for trend across CHeKS score quintiles (29). Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the association between CHeKS score and vascular access use at baseline, 3 mo, and 6 mo after enrollment, with a priori adjustment for potential confounding variables including age, sex, race, education, and the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Subjects with missing data were not included in the analyses. Logistic regression models did not demonstrate evidence of collinearity between covariates and were satisfactory by the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (30). Evaluation for effect moderation by education level in the adjusted analyses was determined by assessment of p-values for interaction. All tests were two-tailed and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata 8.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Study Population

A total of 490 incident CHD patients completed the baseline CHeKS and had baseline measures available. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median age was 64 yr, 46% were female, and 33% were African American. The majority of the patients had completed high school (75%) and more than 50% had a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. The characteristics of the patients in this study did not have any statistically significant differences compared with the 411 patients who were excluded from the original cohort because they lacked baseline information about either knowledge score or access type.

Table 1.

Patient characteristicsa

| Characteristic n = 490 | Median [IQR] or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (n = 488) | 64 [53–74] |

| % Female (n = 489) | 226 (46%) |

| Race (n = 454) | |

| % White | 266 (58%) |

| % African American | 148 (33%) |

| % Other | 40 (9%) |

| % Married (n = 419) | 212 (51%) |

| % Education < High School (n = 458) | 116 (25%) |

| % Diabetes Mellitus | 275 (56%) |

| Baseline clinical characteristics | |

| Hematocrit (%) (n = 475) | 31.5 [28.5–34.5] |

| Albumin (g/dl) (n= 475) | 3.5 [3.2–3.9] |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) (n = 475) | 4.7 [3.9–5.9] |

| Tranferrin saturation (%) (n= 459) | 18.0 [13–24] |

| intact-Parathyroid hormone (ng/L) (n = 297) | 323 [174–574] |

| Access: AVF or AVGa | 126 (26%) |

AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVG, arteriovenous graft; IQR, Interquartile range.

Baseline clinical characteristics were also measured and are shown in Table 1. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) were hematocrit of 31.5% (28.5% to 34.5%), serum albumin of 3.5 (3.2 to 3.9) g/dl, and serum phosphorus of 4.7 (3.9 to 5.9) mg/dl. At initiation of dialysis, only 26% of patients were using an AVF or AVG for dialysis access. The proportion of patients using an AVF or AVG increased over the study period to 41% and 58% at 3 mo and 6 mo, respectively.

Knowledge Test Performance

The median score on the CHeKS administered to patients at baseline was 65% (IQR: 52% to 78%). Areas of poor knowledge, where less than 50% of the patients correctly answered the survey question, included safety of over-the-counter medications for dialysis patients, the role of exercise, and also methods to improve dialysis adequacy. There were 251 patients who also completed the survey 3 mo after dialysis initiation and they scored a median (IQR) of 83% (70% to 91%) correct with a median improvement of 13% (4% to 26%) compared with baseline performance (P < 0.001).

Patient characteristics and their associations with hemodialysis care knowledge are shown in Table 2. The CHeKS score was highly correlated with age, race, and education. Older patients had a lower average score (rho = −0.295; P < 0.001) as did patients with less than a high school education (54% versus 66%; P < 0.001). Patients of white race scored higher than patients of nonwhite race (65% versus 59%; P < 0.001). There was no association found between knowledge survey score and sex, marital status, or diabetes mellitus diagnosis.

Table 2.

Association between baseline Chronic Hemodialysis Knowledge Survey score and patient characteristicsa

| Characteristic n = 490 | Spearman's (rho) or Mean (SD) | Pb |

|---|---|---|

| Age (n = 488) | −0.295 | <0.001 |

| Sex (n = 489) | – | 0.55 |

| Female | 62% (18.7) | – |

| Male | 63% (18.7) | – |

| Race (n = 453) | – | <0.001 |

| White | 65% (18.4) | – |

| Non-white | 59% (18.4) | – |

| Diabetes | – | 0.46 |

| Yes | 62% (19.2) | |

| No | 63% (18.1) | |

| Marital Status (n = 419) | 0.34 | |

| Yes | 64% (18.5) | |

| No | 62% (19.1) | |

| Education (n = 484) | – | <0.0001 |

| Less than high school | 54% (19.0) | – |

| High school or greater | 66% (17.5) | – |

| Baseline clinical characteristics | ||

| Hematocrit (%) (n = 475) | −0.027 | 0.55 |

| Albumin (g/dl) (n = 473) | 0.093 | 0.04 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) (n = 475) | 0.045 | 0.33 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) (n = 459) | 0.005 | 0.73 |

| intact-parathyroid hormone (ng/L) (n = 297) | −0.025 | 0.66 |

| Access: AVF or AVG | 65% (17.7) | 0.05 |

| Catheter | 62% (18.9) |

AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVG, arteriovenous graft.

Spearman's Chi-squared or Wilcoxon rank sum test

There were no statistically significant correlations found between baseline laboratory measures, including serum phosphorus, and performance on the CHeKS (Table 2), except for a modest association with serum albumin (r = 0.093; P = 0.04). Patients with higher CHeKS scores were more likely to have higher baseline serum albumin levels. Results were similar if the clinical measures were included as raw values or categorized based on NKF-KDOQI recommended goals.

Knowledge Test Scores and Vascular Access

Lower knowledge scores were found in patients who used a dialysis catheter at initiation compared with those who used an AVF or AVG (P = 0.05) (Table 2). For patients who scored in the lowest quintile of CHeKS scores (scoring <50%), 20% used an AVF or AVG at baseline; and for patients in the two highest CHeKS score quintiles, 29% to 35% used an AVF or AVG (p-trend = 0.08). Patients who scored the equivalent of one SD higher (or 20 percentage points) higher on the CHeKS were 25% more likely to use an AVF or AVG at initiation of dialysis (Odds Ratio [OR] [95% CI]: 1.25 [1.00, 1.57]; P = 0.05) compared with use of a catheter for dialysis access. This was statistically significant even after adjustment for potential confounding factors, including age, sex, race, education, and diabetes status (Table 3). At 6 mo after dialysis initiation, use of an AVF or AVG had increased overall, and patients in the two highest CHeKS score quintiles continued to have a greater proportion of patients using an AVF or AVG compared with patients in the lowest quintile (63 to 66% versus 45%, respectively; p-trend = 0.008). In multivariable analyses at 3 mo and 6 mo after dialysis initiation, patients who scored 20 percentage points higher on the CHeKS at baseline were more likely to be using an AVF or AVG for dialysis access (OR [95% CI] = 1.49[1.16, 1.93]; P = 0.002 and 1.33[1.03, 1.72]; P = 0.03, respectively) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted Logistic Regression Analyses: Association between baseline CHeKS score and use of an arteriovenous fistula or graft at baseline and three- and six-months after dialysis initiation

| Characteristica | OR [95% CI]

|

P | OR [95% CI]

|

P | OR [95% CI]

|

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline n = 426 | 3–Months n = 395 | 6–Months n = 367 | ||||

| Dialysis Care Knowledge CHeKS Score (20% points) | 1.34 [1.02, 1.76] | 0.03 | 1.49 [1.16, 1.93] | 0.002 | 1.33 [1.03, 1.72] | 0.03 |

| Age (per year) | 1.00 [0.99, 1.02] | 0.69 | 1.00 [0.99, 1.02] | 0.81 | 1.00 [0.98, 1.01] | 0.64 |

| Sex (Female versus Male) | 1.22 [0.78, 1.90] | 0.38 | 1.18 [0.78, 1.78] | 0.44 | 1.10 [0.72, 1.68] | 0.64 |

| Race (Non-white versus White) | 1.07 [0.66, 1.73] | 0.78 | 1.04 [0.67, 1.63] | 0.85 | 0.95 [0.61, 1.50] | 0.84 |

| Education (HS or greater versus less than HS) | 0.88 [0.52, 1.50] | 0.65 | 0.91 [0.56, 1.48] | 0.70 | 0.88 [0.54, 1.45] | 0.62 |

| Diabetes (Yes versus no) | 1.08 [0.69, 1.69] | 0.74 | 1.25 [0.82, 1.90] | 0.30 | 1.24 [0.81, 1.90] | 0.33 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HS, high school.

Adjusted analyses also demonstrated evidence that the association between higher CHeKS score and use of a catheter for dialysis access was significantly different comparing patients with less than a high school education and those with at least a high school education or more (p-interaction = 0.03). In patients with less than a high school education who scored higher on the CHeKS, no association was found with use of an AVF or AVG as initial dialysis access (OR [95% CI]: 0.85[0.51, 1.41]; P = 0.53), but among patients with higher levels of education, those who scored 20 percentage points higher on the CHeKS were 60% more likely to use an AVF or AVG at baseline (OR [95% CI]: 1.60[1.15, 2.24]; P = 0.006). This finding persisted with similar results at the 3-mo interval after dialysis initiation; however, there was no statistical evidence of effect modification at the 6-mo interval.

Discussion

In this study, patient hemodialysis knowledge was fair, with specific areas of poor knowledge. Lower knowledge scores were associated with older age, nonwhite race, and fewer years of education. Although there were few associations found between CHeKS score and clinical measures, there was a moderate and persistent association between higher scores and use of an AVF or AVG for dialysis access, especially in patients who reported a higher level of education.

Education programs for chronic kidney disease patients have been shown to delay the time to dialysis and even improve survival (31,32). However, 36% of patients with chronic kidney disease stages 3 to 5, seen by a nephrologist, report having no knowledge about hemodialysis (33). Our study supports that patients who go on to receive hemodialysis may indeed have moderate to low levels of dialysis knowledge.

Our study also suggests that patients with greater knowledge about dialysis at initiation are more likely to use an AVF or AVG. Predialysis programs may increase permanent access use at dialysis initiation by many mechanisms (34). In our study, patients with higher dialysis knowledge were also more likely to be using an arteriovenous permanent access 3 and 6 mo after initiation, suggesting that greater knowledge at the start of dialysis may have persistent impact on dialysis care. We are unable to comment on the independent association of dialysis knowledge and access use because we do not have a measure of predialysis care. However, assuming that once patients initiate dialysis they are exposed to similar education and referrals for access placement, we might hypothesize that if predialysis care was the dominant factor, then the association between knowledge and permanent access at 6 mo after dialysis initiation would not persist. Another explanation may be that patients who have more dialysis knowledge may also have the overall skills to interact with the health care system more effectively.

Interestingly, in patients with less than a high school education there was no significant association between dialysis knowledge and use of a permanent dialysis access. For this subgroup of patients, there may be additional barriers to successful permanent access placement such that knowledge itself has less of an impact. Another reason for the difference seen by educational level may be that years of educational attainment may not reflect the skill set of the patient. Even patients who report a high school education may still have significant deficits with the interpretation and application of health care information, such as low health literacy skills (35). Therefore, dialysis knowledge (CHeKS score) is a measure that more specifically characterizes the patients’ skills and their association with the access type used. This exploratory subgroup analysis needs replication and verification in a larger chronic dialysis population.

In this study, the only statistically significant association between patient dialysis knowledge and laboratory measures was for serum albumin. Lower serum albumin has been shown to be associated with a higher risk of mortality and a lower reported general health status in dialysis patients (36,37). Patients with more severe kidney, or comorbid, disease may have lower knowledge scores and also have lower serum albumin due to a more impaired nutritional profile (38). Additional studies exploring other markers of severity of illness, such as inflammatory markers and more detailed nutritional assessments, may give additional insight into this preliminary finding. Despite our reasonable sample size, this study was underpowered to detect significant associations with dialysis knowledge and other clinical measures.

The CHeKS was a reliable survey to evaluate dialysis knowledge of CHD patients, was easy to administer, and differentiated patients with poor hemodialysis knowledge. Other kidney knowledge surveys (22,39,40) have evaluated a broad range of kidney information in both chronic kidney disease and dialysis patients. Similar to other studies, lower knowledge was associated with older age and less education (25–27). Nonwhite race (78% African American) was associated with lower knowledge, and it is important to note that in another recent study African American race was associated with lower perceived knowledge of dialysis therapies (33). The mechanisms underlying this disparity remain unknown, and further investigation is needed.

There are several limitations of this study. First, there is the possibility of residual confounding. Knowledge may be associated with other variables, including income, social support, and health literacy, which may also be related to clinical outcomes. Second, this study included patients who were eligible for participation in a renal disease management educational intervention. Therefore, the findings may not be generalizable to all dialysis patients. Third, although there were no differences in characteristics between patients beginning dialysis who completed the CHeKS and those who did not, there is the possibility of selection bias because not every patient in this program completed the survey. Additionally, a limitation of CHeKS is that it was not evaluated for test-retest reliability. However, the survey did demonstrate responsiveness in those who completed it at both baseline and 3 mo. Use of the CHeKS in larger, prospective cohort, or educational intervention trials will provide further evaluation for its role in describing hemodialysis patient knowledge, as well as its predictive validity of CHD clinical outcomes. Finally, all patients in this project were exposed to an educational intervention, and therefore there is not an adequate control group to explore over time the effect of improvement of knowledge scores on the outcomes.

Conclusions

Evaluation of patient dialysis knowledge is a rapid and easy method to identify patients who may be at higher risk of not using an arteriovenous access both at dialysis initiation and after starting dialysis, and therefore may be candidates for targeted educational interventions. Further evaluation of the impact of patient dialysis knowledge and the improvement in knowledge level in larger studies is needed to better understand its relationship with clinical measures and to provide guidance for improved CHD patient education.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Thomas and Marie Hobbs, Fresenius Medical Care, for their data management assistance. This work was presented in part as an abstract and poster presentation at the National Kidney Foundation Clinical Meeting April 10 through 14, 2007, (Orlando, Florida) AJKD 2007; 49 (4):A33. The RightStart program was supported by a grant from Amgen, Inc. However, Amgen, Inc. did not provide support for the analyses presented, nor did the company review this manuscript. Dr. Cavanaugh is supported by a National Kidney Foundation Young Investigator Grant and grant K23 DK080952-01, Dr. Ikizler by grant K24 DK62849, and Dr. Elasy by grants K24 DK77875 and P60 DK 020593 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Astor BC, Eustace JA, Powe NR, Klag MJ, Fink NE, Coresh J: Type of vascular access and survival among incident hemodialysis patients: The Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for ESRD (CHOICE) Study. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1449–1455, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhingra RK, Young EW, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Leavey SF, Port FK: Type of vascular access and mortality in U.S. hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 60: 1443–1451, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xue JL, Dahl D, Ebben JP, Collins AJ: The association of initial hemodialysis access type with mortality outcomes in elderly Medicare ESRD patients. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 1013–1019, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allon M, Daugirdas J, Depner TA, Greene T, Ornt D, Schwab SJ: Effect of change in vascular access on patient mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 47: 469–477, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins AJ, Foley R, Herzog C, Chavers B, Gilbertson D, Ishani A, Kasiske B, Liu J, Mau LW, McBean M, Murray A, St Peter W, Xue J, Fan Q, Guo H, Li Q, Li S, Li S, Peng Y, Qiu Y, Roberts T, Skeans M, Snyder J, Solid C, Wang C, Weinhandl E, Zaun D, Zhang R, Arko C, Chen SC, Dalleska F, Daniels F, Dunning S, Ebben J, Frazier E, Hanzlik C, Johnson R, Sheets D, Wang X, Forrest B, Constantini E, Everson S, Eggers P, Agodoa L: Excerpts from the United States Renal Data System 2007 annual data report. Am J Kidney Dis 51: S1–S320, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacson E, Jr., Lazarus JM, Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA, Hakim RM: Balancing fistula first with catheters last. Am J Kidney Dis 50: 379–395, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Kidney Foundation: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39: S1–S266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Nephrology Nurses’ Association. ANNA position statements. Nephrol Nurs J 35: 301–318, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piccoli GB, Mezza E, Pacitti A, Iacuzzo C, Bechis F, Quaglia M, Anania P, Garofletti Y, Martino B, Peirano G, Agli I, Jeantet A, Segoloni GP: Patient knowledge and interest on dialysis efficiency: A survey. Int J Artif Organs 25: 129–135, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin HR, Jenckes M, Fink NE, Meyer K, Wu AW, Bass EB, Levin N, Powe NR: Patient's view of dialysis care: Development of a taxonomy and rating of importance of different aspects of care. CHOICE Study. Choices for Healthy Outcomes in Caring for ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis 30: 793–801, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swartz MD, Robinson K, Davy T, Politoski G: The role of patients in the implementation of the National Kidney Foundation-Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative. Adv Ren Replace Ther 6: 52–58, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grover SA, Lowensteyn I, Joseph L, Kaouache M, Marchand S, Coupal L, Boudreau G: Patient knowledge of coronary risk profile improves the effectiveness of dyslipidemia therapy: The CHECK-UP study: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 167: 2296–2303, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM: Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care 24: 561–587, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothman RL, Malone R, Bryant B, Wolfe C, Padgett P, DeWalt DA, Weinberger M, Pignone M: The Spoken Knowledge in Low Literacy in Diabetes scale: A diabetes knowledge scale for vulnerable patients. Diabetes Educ 31: 215–224, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stromberg A: The crucial role of patient education in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 7: 363–369, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mason J, Khunti K, Stone M, Farooqi A, Carr S: Educational interventions in kidney disease care: A systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis 51: 933–951, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas LK, Sargent RG, Michels PC, Richter DL, Valois RF, Moore CG: Identification of the factors associated with compliance to therapeutic diets in older adults with end stage renal disease. J Ren Nutr 11: 80–89, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juergensen PH, Gorban-Brennan N, Finkelstein FO: Compliance with the dialysis regimen in chronic peritoneal dialysis patients: Utility of the pro card and impact of patient education. Adv Perit Dial 20: 90–92, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashurst Ide B, Dobbie H: A randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention to improve phosphate levels in hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr 13: 267–274, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford JC, Pope JF, Hunt AE, Gerald B: The effect of diet education on the laboratory values and knowledge of hemodialysis patients with hyperphosphatemia. J Ren Nutr 14: 36–44, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMurray SD, Johnson G, Davis S, McDougall K: Diabetes education and care management significantly improve patient outcomes in the dialysis unit. Am J Kidney Dis 40: 566–575, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtin RB, Sitter DC, Schatell D, Chewning BA: Self-management, knowledge, and functioning and well-being of patients on hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J 31: 378–386, 396; quiz 387, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wingard RL, Pupim LB, Krishnan M, Shintani A, Ikizler TA, Hakim RM: Early intervention improves mortality and hospitalization rates in incident hemodialysis patients: RightStart program. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 1170–1175, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeVellis RF. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. Newbury Park, California, Sage, 1991, pp 25–26

- 25.Kriegsman DM, Penninx BW, van Eijk JT, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJ: Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients’ self-reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin Epidemiol 49: 1407–1417, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson CF, Boyd CM, Carlson MC, Griswold ME, Guralnik JM, Fried LP: Agreement between self-report of disease diagnoses and medical record validation in disabled older women: Factors that modify agreement. J Am Geriatr Soc 52: 123–127, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ: Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol 57: 1096–1103, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clinical practice guidelines for hemodialysis adequacy, update 2006. Am J Kidney Dis 48 Suppl 1: S2–S90, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuzick J: A Wilcoxon-type test for trend. Stat Med 4: 87–90, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW, Jr.: A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models. Am J Epidemiol 115: 92–106, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Devins GM, Mendelssohn DC, Barre PE, Binik YM: Predialysis psychoeducational intervention and coping styles influence time to dialysis in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 693–703, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devins GM, Mendelssohn DC, Barre PE, Taub K, Binik YM: Predialysis psychoeducational intervention extends survival in CKD: A 20-year follow-up. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 1088–1098, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finkelstein FO, Story K, Firanek C, Barre P, Takano T, Soroka S, Mujais S, Rodd K, Mendelssohn D: Perceived knowledge among patients cared for by nephrologists about chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease therapies. Kidney Int 74: 1178–1184, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindberg JS, Husserl FE, Ross JL, Jackson D, Scarlata D, Nussbaum J, Cohen A, Elzein H: Impact of multidisciplinary, early renal education on vascular access placement. Nephrol News Issues 19: 35–36, 41–43, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothman RL, Housam R, Weiss H, Davis D, Gregory R, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Elasy TA: Patient understanding of food labels: The role of literacy and numeracy. Am J Prev Med 31: 391–398, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dwyer JT, Larive B, Leung J, Rocco M, Burrowes JD, Chumlea WC, Frydrych A, Kusek JW, Uhlin L: Nutritional status affects quality of life in Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study patients at baseline. J Ren Nutr 12: 213–223, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaysen GA, Johansen KL, Cheng SC, Jin C, Chertow GM: Trends and outcomes associated with serum albumin concentration among incident dialysis patients in the United States. J Ren Nutr 18: 323–331, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pupim LB, Ikizler TA: Assessment and monitoring of uremic malnutrition. J Ren Nutr 14: 6–19, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chambers JK, Boggs DL: Development of an instrument to measure knowledge about kidney function, kidney failure, and treatment options. Anna J 20: 637–642, 650; discussion 643, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devins GM, Binik YM, Mandin H, Letourneau PK, Hollomby DJ, Barre PE, Prichard S: The Kidney Disease Questionnaire: A test for measuring patient knowledge about end-stage renal disease. J Clin Epidemiol 43: 297–307, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]