Abstract

Background and objectives: Pseudomonas peritonitis is a serious complication of peritoneal dialysis. To date, there as been no comprehensive, multicenter study of this condition.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: The predictors, treatment, and clinical outcomes of Pseudomonas peritonitis were examined by binary logistic regression and multilevel, multivariate Poisson regression in all Australian PD patients in 66 centers between 2003 and 2006.

Results: A total of 191 episodes of Pseudomonas peritonitis (5.3% of all peritonitis episodes) occurred in 171 individuals. Its occurrence was independently predicted by Maori/Pacific Islander race, Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander race, and absence of baseline peritoneal equilibration test data. Compared with other organisms, Pseudomonas peritonitis was associated with greater frequencies of hospitalization (96 versus 79%; P = 0.006), catheter removal (44 versus 20%; P < 0.001), and permanent hemodialysis transfer (35 versus 17%; P < 0.001) but comparable death rates (3 versus 2%; P = 0.4). Initial empiric antibiotic choice did not influence outcomes, but subsequent use of dual anti-pseudomonal therapy was associated with a lower risk for permanent hemodialysis transfer (10 versus 38%, respectively; P = 0.03). Catheter removal was associated with a lower risk for death than treatment with antibiotics alone (0 versus 6%; P < 0.05).

Conclusions: Pseudomonas peritonitis is associated with high rates of catheter removal and permanent hemodialysis transfer. Prompt catheter removal and use of two anti-pseudomonal antibiotics are associated with better outcomes.

Peritonitis caused by Pseudomonas species is a serious complication in patients who are on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (PD) and often is associated with poor response to conventional antibiotics and high rates of catheter removal (1–3). The 2005 update of the International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) guidelines for management of PD-related infections recommends the use of dual antibiotic therapy, which includes either a quinolone, third-generation cephalosporin or aminoglycoside and prompt catheter removal in refractory cases (4); however, these recommendations are based on evidence provided by limited single-center observational studies (5,6). There has not been a comprehensive examination of different therapeutic approaches to Pseudomonas peritonitis within each of these centers. The aim of this study was to examine the frequency, predictors, treatment, and clinical outcomes of Pseudomonas peritonitis in all Australian PD patients in 66 PD centers.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The study included all Australian adult patients from the ANZDATA Registry who were receiving PD between October 1, 2003 (when detailed peritonitis data started to be collected), and December 31, 2006. The data collected included demographic data, cause of primary renal disease, comorbidities at the start of dialysis (coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking status), body mass index, late referral (defined as commencement of dialysis within 3 mo of referral to a nephrologist), microbiology of peritonitis episodes (up to three organisms for polymicrobial episodes), and the initial and subsequent antibiotic treatment regimens. The organism responsible for Pseudomonas peritonitis was coded as P. aeruginosa, P. cepacia, P. stutzeri, Pseudomonas other, or Pseudomonas unknown. In cases of polymicrobial peritonitis, Pseudomonas peritonitis was recorded when a Pseudomonas species was at least one of the isolated organisms. Center size was categorized according to quartiles: Small (<11 patients during the study period), small-medium (11 to 38 patients), medium-large (39 to 98 patients), and large (>99 patients).

The outcomes examined were peritonitis relapse, repeat peritonitis, peritonitis-associated hospitalization, catheter removal, temporary or permanent transfer to hemodialysis, and patient death. Peritonitis relapse was defined as occurrence of an episode of peritonitis within 4 wk of the last antibiotic dose (or within 5 wk when intermittent vancomycin was used) for peritonitis caused by the same organism. Repeat peritonitis was defined as occurrence of an episode of peritonitis >4 wk after the last antibiotic dose (or >5 wk when intermittent vancomycin was used) for peritonitis caused by the same organism.

Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, mean ± SD for continuous variables, and median and interquartile range for nonparametric data. Differences between two groups of patients were analyzed by χ2 test for categorical data, unpaired t test for continuous parametric data, and Mann-Whitney test for continuous nonparametric data. The independent predictors of Pseudomonas peritonitis were determined by multivariate Poisson regression using backward stepwise elimination (7). First-order interaction terms between the significant covariates were examined for all analyses. For Poisson analyses, the correlation between observations (intraclass correlation) was taken into account by using a multilevel modeling technique: The hierarchical model took into account clustering on the basis of state of residence, treating unit, and individual patient (because patients could have had more than one event). Peritonitis outcomes were evaluated by multivariable binary logistic regression analysis. Data were analyzed using the software packages SPSS 12.0 for Windows (SPSS, North Sydney, Australia) and Stata/SE 10.1 (College Station, TX). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Population Characteristics

A total of 4675 patients received PD in Australia during the study period (October 1, 2003, to December 31, 2006). They were followed for 6002 patient-years. A total of 191 episodes of Pseudomonas peritonitis occurred in 171 individuals. Pseudomonas species accounted for 5.3% of all 3594 peritonitis episodes. The rate of Pseudomonas peritonitis was 0.032 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.028 to 0.037) episodes per patient-year of treatment. The organisms isolated included P. aeruginosa (n = 116 [61%]), P. stutzeri (n = 15 [8%]), Pseudomonas other (n = 39 [20%]), and Pseudomonas species unknown (n = 21 [11%]). Additional non-Pseudomonas organisms were isolated in 42 (22%) episodes of Pseudomonas peritonitis, including coagulase-negative staphylococci (n = 5), methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (n = 2), streptococci (n = 2), enterococci (n = 4), other Gram-positive organisms (n = 2), Acinetobacter (n = 2), Escherichia coli (n = 9), Klebsiella (n = 1), Serratia (n = 2), Proteus (n = 2), Citrobacter (n = 2), Enterobacter (n = 5), other Gram-negative organisms (n = 5), Candida (n = 1), and other organisms (n = 7). Thirty-three episodes of peritonitis were associated with two organisms, and nine episodes were associated with three organisms. A total of 155 patients experienced one episode of Pseudomonas peritonitis during the study period, 13 experienced two episodes, two experienced three episodes, and one experienced four episodes.

Predictors of Pseudomonas Peritonitis

The characteristics of patients who did and did not experience Pseudomonas peritonitis are shown in Table 1. On univariate analysis, patients who experienced Pseudomonas peritonitis during the study period were more likely to be Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander or Maori and Pacific Islander peoples or living in the Northern Territory than patients who did not experience Pseudomonas peritonitis. They were also significantly less likely to be living in Victoria.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all Australian PD patients who did and did not experience Pseudomonas peritonitis at any stage during the period 2003 through 2006a

| Characteristic | Pseudomonas Peritonitis (n = 171) | No Pseudomonas Peritonitis (n = 4504) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr; mean ± SD) | 59.3 ± 19.3 | 61.6 ± 16.6 | 0.080 |

| Women (n [%]) | 73 (43) | 2053 (46) | 0.500 |

| Racial origin (n [%]) | 0.001 | ||

| white | 122 (71) | 3459 (77) | |

| Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander | 23 (13) | 365 (8) | |

| Maori/Pacific Islander | 8 (5) | 73 (2) | |

| Asian | 12 (7) | 429 (10) | |

| other | 6 (4) | 178 (4) | |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean ± SD) | 25.9 ± 6.4 | 25.4 ± 5.7 | 0.400 |

| eGFR at dialysis start (ml/min per 1.73 m2; mean ± SD) | 7.1 ± 5.0 | 7.3 ± 10.5 | 0.800 |

| Late referral (n [%]) | 46 (27) | 1065 (24) | 0.300 |

| ESRF cause (n [%]) | 0.200 | ||

| chronic glomerulonephritis | 50 (29) | 1273 (28) | |

| diabetic nephropathy | 41 (24) | 1278 (28) | |

| renovascular disease | 18 (11) | 621 (14) | |

| polycystic kidneys | 7 (4) | 189 (4) | |

| reflux nephropathy | 8 (5) | 189 (4) | |

| other | 29 (17) | 616 (14) | |

| unknown | 18 (11) | 278 (6) | |

| Current smoker (n [%]) | 18 (11) | 539 (12) | 0.200 |

| Chronic lung disease (n [%]) | 22 (13) | 577 (13) | 1.000 |

| Coronary artery disease (n [%]) | 58 (34) | 1609 (36) | 0.600 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (n [%]) | 28 (16) | 1018 (23) | 0.800 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (n [%]) | 25 (15) | 583 (13) | 0.500 |

| Diabetes (n [%]) | 57 (33) | 1681 (37) | 0.300 |

| Peritoneal transport status (n [%]) | 0.800 | ||

| high | 14 (8) | 457 (10) | |

| high average | 64 (37) | 1647 (37) | |

| low average | 37 (22) | 1041 (23) | |

| low | 9 (5) | 189 (4) | |

| unknown/not specified | 47 (27) | 1170 (26) | |

| Centre size (no. of PD patients; n [%]) | 0.600 | ||

| small (≤10) | 2 (1) | 53 (1) | |

| small-medium (11 to 38) | 15 (9) | 306 (7) | |

| medium-large (39 to 98) | 32 (19) | 996 (22) | |

| large (≥99) | 122 (71) | 3149 (70) | |

| State | <0.001 | ||

| New South Wales | 77 (45) | 1755 (39) | |

| Northern Territory | 8 (5) | 77 (2) | |

| Queensland | 37 (22) | 918 (20) | |

| South Australia | 13 (8) | 282 (6) | |

| Tasmania | 1 (1) | 76 (2) | |

| Victoria | 14 (8) | 946 (21) | |

| Western Australia | 21 (12) | 450 (10) |

BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated GFR; ESRF, end-stage renal failure; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Multivariate Poisson regression using a multilevel hierarchical model (accounting for intraclass correlation based on state of residence, treating unit, and individual patient) demonstrated that the occurrence of Pseudomonas peritonitis was significantly and independently predicted by Maori and Pacific Islander racial origin (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR] 3.53; 95% CI 1.43 to 8.72) and Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander racial origin (IRR 2.08; 95% CI 1.10 to 3.92) and the absence of baseline data for peritoneal transport status (IRR 2.60; 95% CI 1.34 to 5.07). There was a trend to lower incidence in female compared with male patients (IRR 0.70; 95% CI 0.49 to 1.01) and for patients aged 50 to 60 yr compared with other age groups (IRR 0.60; 0.35 to 1.05). The development of Pseudomonas peritonitis was not associated with kidney function at dialysis commencement, current smoking status, chronic lung disease, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, end-stage renal failure cause, or late referral within 3 mo of needing to start dialysis.

Effect of Previous Peritonitis Episodes on Occurrence of Pseudomonas Peritonitis

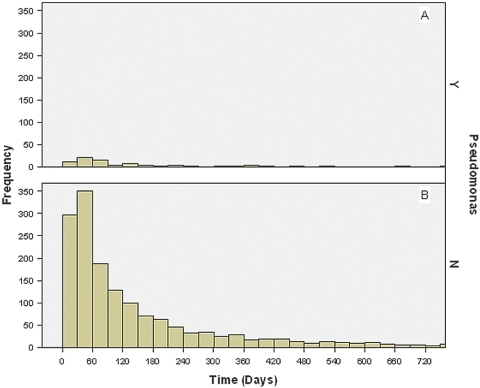

A history of previous peritonitis was not significantly different between Pseudomonas and non-Pseudomonas peritonitis episodes (43 versus 45%, respectively; P = 0.6). Moreover, the time elapsed between a previous peritonitis episode and the subsequent one was similar between Pseudomonas peritonitis (median period 82.00 d; interquartile range [IQR] 40.75 to 182.00 d) and non-Pseudomonas peritonitis (median 77.00 d; IQR 35.00 to 184.00 d; P = 0.4), such that the probability that an episode of subsequent peritonitis would be caused by a Pseudomonas species as opposed to an organism other than Pseudomonas remained comparable over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A and B) Histograms demonstrating the temporal occurrence of Pseudomonas peritonitis (A)and non-Pseudomonas peritonitis (B) in relation to a previous episode of treated non-Pseudomonas peritonitis in Australian peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients who had experienced more than one episode of peritonitis during the study period.

Treatment of Pseudomonas Peritonitis

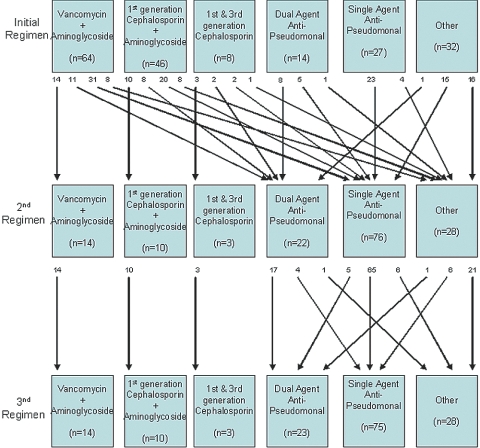

The vast majority of patients with Pseudomonas peritonitis were initially treated with either intraperitoneal vancomycin or cephazolin in combination with gentamicin as empiric therapy (Figure 2). Once culture results became known at a median time of day 2, the majority of patients were changed to an alternative regimen. The most common agent prescribed in second and third antibiotic regiments was ciprofloxacin, which was most often prescribed as monotherapy. Although the ISPD guidelines recommend treatment of Pseudomonas peritonitis with at least two agents that are active against Pseudomonas species (4), only 40 (21%) Pseudomonas peritonitis episodes received such combination therapy at any stage. The most common combination used was ciprofloxacin and gentamicin, followed by ticarcillin and gentamicin and by ceftazidime and gentamicin. Overall, the median total antibiotic course duration was 16 d (Table 2). Heparin was administered to dialysate in 20 (13%) episodes of Pseudomonas peritonitis. Streptokinase was not instilled in the PD catheter in any episodes of Pseudomonas peritonitis, and only nine (6%) patients with Pseudomonas peritonitis received concomitant prophylactic nystatin therapy.

Figure 2.

Antimicrobial agents prescribed in initial, second, and third antibiotic regimens for Pseudomonas peritonitis episodes in Australian PD patients, 2003 through 2006. Numbers at arrow origins depict number of peritonitis episodes. Dual-agent anti-pseudomonal therapy comprised, in descending order of frequency, ciprofloxacin + aminoglycoside (usually gentamicin), ticarcillin + aminoglycoside, ceftazidime + aminoglycoside, and piperacillin + aminoglycoside. Single-agent anti-pseudomonal therapy (excluding those who received aminoglycoside in combination with either vancomycin or first-generation cephalosporin) comprised, in descending order of frequency, ciprofloxacin, aminoglycoside (usually gentamicin), ticarcillin, piperacillin, ceftazidime, and cefepime.

Table 2.

Treatment characteristics and clinical outcomes of PD-associated peritonitis caused by Pseudomonas or other organisms in Australia, 2003 through 2006. Results are expressed as number (%) or median days [interquartile range]a

| Outcome | Pseudomonas Peritonitis (n = 191 Episodes) | Non-Pseudomonas Peritonitis (n = 3403 Episodes) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | |||

| change to second antibiotic regimen (n [%]) | 126 (66) | 1884 (55) | 0.005 |

| time to second antibiotic regimen (d; median [IQR]) | 2.00 (1.00 to 4.00) | 3.00 (2.00 to 5.00) | 0.030 |

| change to third antibiotic regimen (n [%]) | 48 (25) | 449 (13) | <0.001 |

| time to third antibiotic regimen (d; median [IQR]) | 6.00 (4.00 to 11.00) | 7.00 (4.00 to 10.00) | 0.400 |

| total antibiotic treatment duration (d; median [IQR]) | 16.00 (9.75 to 23.00) | 14.00 (8.00 to 19.00) | 0.001 |

| Relapse (n [%]) | 17 (9) | 485 (14) | 0.040 |

| Hospitalization | |||

| n (%) | 150 (79) | 2354 (69) | 0.006 |

| duration (d; median [IQR]) | 9.00 (5.00 to 20.00) | 6.00 (3.00 to 11.00) | <0.001 |

| Catheter removal | |||

| n (%) | 84 (44) | 691 (20) | <0.001 |

| time to occurrence (d; median [IQR]) | 5.50 (3.00 to 11.00) | 6.00 (3.00 to 13.00) | 0.400 |

| Temporary hemodialysis | |||

| n (%) | 20 (10) | 132 (4) | <0.001 |

| time to occurrence (d; median [IQR]) | 7.50 (4.25 to 12.50) | 6.00 (3.00 to 11.50) | 0.500 |

| duration (d; median [IQR]) | 73.50 (51.00 to 109.50) | 67.00 (20.50 to 103.00) | 0.300 |

| Permanent hemodialysis | |||

| n (%) | 66 (35) | 569 (17) | <0.001 |

| time to occurrence (d; median [IQR]) | 6.00 (4.00 to 11.75) | 7.00 (4.00 to 13.00) | 0.700 |

| Death | |||

| n (%) | 6 (3) | 76 (2) | 0.400 |

| time to death (d; median [IQR]) | 19.00 (5.00 to 26.00) | 11.00 (3.00 to 22.25) | 0.400 |

IQR, interquartile range.

Outcomes of Pseudomonas Peritonitis

Pseudomonas peritonitis episodes commonly resulted in relapse (9%), hospitalization (79%), catheter removal (44%), permanent hemodialysis transfer (35%), and death (3%; Table 2). Compared with non-Pseudomonas peritonitis, Pseudomonas peritonitis was associated with a significantly lower risk for relapse and greater frequencies of hospitalization, catheter removal, and permanent hemodialysis transfer, as well as a longer duration of hospitalization (Table 2). The risk for death was higher with Pseudomonas peritonitis, although the difference was not statistically significant. The treatment and outcomes of Pseudomonas peritonitis were broadly comparable between single-organism and polymicrobial infections (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment characteristics and clinical outcomes of PD-associated peritonitis caused by Pseudomonas alone or in association with other organisms (polymicrobial peritonitis) in Australia 2003 through 2006

| Outcome | Pseudomonas Alone (n = 145 Episodes) | Pseudomonas and Other Organisms (n = 46 Episodes) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | |||

| change to second antibiotic regimen (n [%]) | 91 (63) | 35 (76) | 0.14 |

| time to second antibiotic regimen (d; median [IQR]) | 3.00 (1.00 to 4.00) | 2.00 (1.00 to 4.00) | 0.70 |

| change to third antibiotic regimen (n [%]) | 32 (22) | 16 (35) | 0.12 |

| time to third antibiotic regimen (d; median [IQR]) | 6.00 (4.00 to 11.00) | 6.00 (3.00 to 7.75) | 0.40 |

| total antibiotic treatment duration (d; median [IQR]) | 16.00 (9.00 to 22.00) | 15.00 (10.00 to 24.25) | 0.50 |

| Relapse (n [%]) | 12 (8) | 5 (11) | 0.60 |

| Hospitalization | |||

| n (%) | 113 (78) | 37 (80) | 0.70 |

| duration (d; median [IQR]) | 9.00 (4.25 to 20.00) | 14.00 (7.00 to 21.00) | 0.20 |

| Catheter removal | |||

| n (%) | 63 (43) | 21 (46) | 0.80 |

| time to occurrence (d; median [IQR]) | 5.00 (3.00 to 9.00) | 10.00 (4.00 to 13.00) | 0.10 |

| Temporary hemodialysis | |||

| n (%) | 17 (12) | 3 (7) | 0.30 |

| time to occurrence (d; median [IQR]) | 7.00 (4.00 to 12.00) | 10.00 (4.00 to 24.00) | 0.60 |

| duration (d; median [IQR]) | 69.00 (45.50 to 95.00) | 127.00 (51.00 to 161.00) | 0.30 |

| Permanent hemodialysis | |||

| n (%) | 46 (32) | 20 (43) | 0.14 |

| time to occurrence (d; median [IQR]) | 6.00 (3.00 to 14.00) | 6.00 (5.00 to 12.00) | 0.50 |

| Death | |||

| n (%) | 4 (3) | 2 (4) | 0.60 |

| time to death (d; median [IQR]) | 19.00 (2.50 to 50.00) | 21.00 (16.00 to 26.00) | 0.70 |

The administration of vancomycin, cephalosporin, or another agent in the initial empiric antibiotic regimen did not significantly influence Pseudomonas peritonitis outcomes. Episodes of Pseudomonas peritonitis that were treated with at least two anti-pseudomonal agents in combination at any stage were significantly less likely to be complicated by the need for permanent hemodialysis transfer than peritonitis episodes that did not receive such treatment (10 versus 38%, respectively; P = 0.03); however, there were no differences between these groups with respect to rates of relapse (8 versus 9%; P = 0.7), hospitalization (83 versus 77%; P = 0.5), catheter removal (38 versus 46%; P = 0.4), or death (3 versus 3%; P = 0.8).

Catheter removal was associated with a significantly lower risk for death than treatment with antibiotics alone (0 versus 6%; odds ratio [OR] 0.54; 95% CI 0.48 to 0.62; P < 0.05). Among the 84 episodes of Pseudomonas peritonitis in which catheters were removed, there was no significant difference in rates of permanent hemodialysis transfer between cases in which the catheter was removed within 5 d of peritonitis onset (n = 35 [83%]) and those in which the catheter was removed later than 5 d (n = 29 [69%]; P = 0.12; Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of timing of catheter removal on subsequent clinical outcomes in 142 patients with Pseudomonas peritonitis requiring catheter removal

| Characteristic | No. (%) of Days from Peritonitis Onset to Catheter Removal

|

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 (n = 42) | >5 (n = 42) | ||

| Permanent hemodialysis transfer | 35 (83) | 29 (69) | 0.12 |

| Death | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

Using multivariable binary logistic regression to determine the independent predictors of Pseudomonas peritonitis outcomes, isolation of P. aeruginosa was associated with an increased risk for catheter removal (OR 3.39; 95% CI 1.05 to 10.90) compared with other Pseudomonas species but did not significantly influence other peritonitis outcomes. The presence of polymicrobial peritonitis or choice of initial antibiotic regimen also did not influence any of the clinical outcomes evaluated. Hospitalization was less likely in Asian patients (OR 0.030; 95% CI 0.003 to 0.300) and individuals treated in the Northern Territory (OR 0.020; 95% CI 0.001 to 0.460) and more likely with increasing age (OR 1.04; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.08), presence of coronary artery disease (OR 5.21; 95% CI 1.33 to 20.40), and treatment in New South Wales (OR 5.60; 95% CI 1.28 to 24.50). Catheter removal was independently predicted by coronary artery disease (OR 3.20; 95% CI 1.40 to 7.30), diabetes (OR 2.57; 95% CI 1.14 to 5.79), missing Peritoneal equilibration test (PET) test data (OR 5.60; 95% CI 1.84 to 17.00), and high average transport status (OR 4.45; 95% CI 1.55 to 12.80). High transport status also tended to be associated with catheter removal (OR 2.60; 95% CI 0.65 to 10.40), whereas individuals who lived in the Northern Territory were less likely to have their catheters removed (OR 0.040; 95% CI 0.003 to 0.610). Permanent hemodialysis transfer was predicted by a history of late referral to a renal unit before renal replacement therapy commencement, missing PET data (OR 7.80; 95% CI 2.26 to 26.90), high transporter status (OR 7.76; 95% CI 1.75 to 34.50), and high average transport status (OR 8.37; 95% CI 2.50 to 28.00). No significant, independent predictors of death were identified.

Discussion

This study, involving 191 cases of PD-associated Pseudomonas peritonitis across 66 PD centers, represents the largest examination to date of the frequency, predictors, treatment, and clinical outcomes of this important condition. Pseudomonas species accounted for 5.3% of all PD-related peritonitis episodes and was associated with greater frequency of hospitalization (79%), catheter removal (44%), and permanent transfer to hemodialysis (35%) and a longer duration of hospitalization compared with non-Pseudomonas peritonitis. The rate of death, however, was not statistically significantly different between groups. The use of two anti-pseudomonal antibiotics resulted in comparable rates of relapse, hospitalization, catheter loss, and death but less likelihood for permanent transfer to hemodialysis; ciprofloxacin and gentamicin was the most common combination used.

The clinical outcomes of Pseudomonas peritonitis in Australia differ from those of Szeto et al. (5), who reported 104 episodes of Pseudomonas peritonitis at a single center in Hong Kong between 1995 and 1999. Pseudomonas peritonitis accounted for 13.2% of all peritonitis cases in their study. P. aeruginosa was found in 90.4% of cases compared with only 61% in our study. Szeto et al. reported a primary response rate of 60.6% but an early relapse rate of 14.4% (15 cases). Inclusion of a third-generation cephalosporin in their initial empiric antibiotic regimen did result in better primary response rates compared with an aminoglycoside, but the complete cure rates did not differ. Throughout the duration of their study, 27 (25.9%) patients underwent catheter removal, and 12 (11.5%) deaths were reported. The higher risk for relapse and death may be related to the higher rate of P. aeruginosa found in their study cohort. An alternative explanation may lie in the predominant (>80%) use of PD as a renal replacement therapy in Hong Kong, where hemodialysis transfer occurs as a last resort such that patients are “switched to hemodialysis only when they have ultrafiltration failure or peritoneal sclerosis” (5). This makes it possible that the high relapse rate may in part reflect attempts to prioritize technique survival over cure of peritonitis episode through catheter removal. Recent antibiotic therapy was also found to be an important risk factor for Pseudomonas peritonitis and subsequent poor response to treatment. This is also in contrast to our findings that past history of peritonitis did not predict the occurrence of subsequent Pseudomonas peritonitis.

It is interesting that we observed that the principal risk factor for Pseudomonas peritonitis was race: Maori and Pacific Islander and Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islanders had a significant higher risk. We previously demonstrated that indigenous racial origin is associated with a higher risk for peritonitis in general, which is independent of the increased risks of diabetes, obesity, and other comorbidities in this group (8). Socioeconomic factors, such as housing conditions, and remoteness of living are likely to be important contributors to the increased risk for Pseudomonas peritonitis in this study but could not be evaluated because of the limited amount of data collected by the ANZDATA Registry. Nevertheless, because hospitals serve areas with differing socioeconomic status, there will have been some accounting for this effect by the hierarchical nature of the Poisson analysis. Previous studies identified a strong association between socioeconomic disadvantage and end-stage kidney disease among indigenous Australians (9). On the basis of residential postcodes, we previously demonstrated that Aboriginal PD patients were more likely to reside in nonmetropolitan than metropolitan areas but were unable to evaluate adequately how remoteness (compared with urban and peri-urban residences) influenced peritonitis outcomes in indigenous patients (8). It is likely, however, that the lower rates of hospitalization and catheter removal in patients in the Northern Territory in this study reflected a high proportion of disadvantaged individuals’ living remotely in relation to their dialysis centers (10). Risk factors for Pseudomonas peritonitis have not been well studied, although Bunke et al. (7) did not observe any association with race in their North American population.

When Pseudomonas is identified by microscopy or culture, the ISPD guidelines recommend removal of an infected catheter, use of two anti-pseudomonal antibiotics, and continuation of antibiotics for at least 2 wk after catheter removal or 3 wk when the catheter is not removed (4). Pseudomonas peritonitis is often related to infection of the catheter and the formation of a biofilm (11,12). The presence of a biofilm leads to its resistance to antibiotic therapy and high relapse rates. Catheter removal should be considered in refractory cases after 4 to 5 d of antibiotics. The findings in our study certainly support the recommendations made by ISPD for catheter removal in cases of catheter infection and use of two anti-pseudomonal antibiotics. We found a high rate of hospitalization, catheter removal, and permanent transfer to hemodialysis with only 21% of patients being treated with two anti-pseudomonal antibiotics. Only the patients who received the combination therapy experienced a significant reduction in the rate of permanent transfer to hemodialysis. The median duration of antibiotics was 16 d, whereas catheters were removed at a median period of 5.5 d from onset of peritonitis. Prescribed antibiotic course durations were therefore slightly shorter (by approximately 4 to 5 d) than those recommended by the ISPD and may have contributed to poorer observed outcomes. Isolation of P. aeruginosa was more predictive of catheter removal (OR 3.39; 95% CI 1.05 to 10.90) compared with other Pseudomonas species. Catheter removal was also more likely in the setting of comorbid illness (coronary artery disease and diabetes), higher peritoneal permeability (which is known to be associated with higher rates of technique failure), and missing PET data (which may reflect a propensity for patient nonattendance or difficulty accessing renal units because of geographic distance). The lower catheter removal rate in the Northern Territory may reflect the rural/remote location of many PD patients such that technique survival might be given higher priority over expeditious cure by catheter removal as a result of the difficulties accessing hemodialysis units. Removal of catheters resulted in a significant reduction in death rate, and no difference in outcome was found when catheters were removed before or after 5 d.

The strengths of this study include its very large sample size, inclusiveness, and robust analyses. We included all patients who received PD in Australia across 66 centers during the study period, such that a variety of centers were included with varying approaches to the treatment of peritonitis. This greatly enhanced the external validity of our findings. These strengths should be balanced against the study's limitations, which included limited depth of data collection. ANZDATA does not collect important information, such as the presence of concomitant exit-site and tunnel infections, patient compliance, individual unit management protocols, laboratory values (e.g., C-reactive protein, dialysate white cell counts), severity of comorbidities, patients’ socioeconomic status or educational backgrounds, antimicrobial susceptibilities of Pseudomonas isolates, prescribed antimicrobial dosages, or routes of antimicrobial administration. Even though we adjusted for a large number of patient characteristics, the possibility of residual confounding could not be excluded. In common with other registries, ANZDATA is a voluntary registry, and there is no external audit of data accuracy, including the diagnosis of peritonitis. Consequently, the possibility of coding/classification bias cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

Pseudomonas peritonitis is a serious, not infrequent complication of PD that is associated with a higher rate of hospitalization, catheter removal, and transfer to hemodialysis. On the basis of the findings in our study, we recommend the use of two anti-pseudomonal antibiotics once Pseudomonas is isolated, for a minimum duration of 2 wk. Initial empiric antibiotic choice did not influence any outcome and therefore should still be based on local centers’ microbial profile. Prompt catheter removal should be considered early in refractory cases.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the substantial contributions of the entire Australia and New Zealand nephrology community (physicians, surgeons, database managers, nurses, renal operators, and patients) in providing information for and maintaining the ANZDATA Registry database.

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Bunke M, Brier ME, Golper TA: Pseudomonas peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients: The Network #9 Peritonitis Study. Am J Kidney Dis 25: 769–774, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juergensen PH, Finkelstein FO, Brennan R, Santacroce S, Ahern MJ: Pseudomonas peritonitis associated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: A six-year study. Am J Kidney Dis 11: 413–417, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mujais S: Microbiology and outcomes of peritonitis in North America. Kidney Int Suppl S55–S62, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Piraino B, Bailie GR, Bernardini J, Boeschoten E, Gupta A, Holmes C, Kuijper EJ, Li PK, Lye WC, Mujais S, Paterson DL, Fontan MP, Ramos A, Schaefer F, Uttley L: Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2005 update. Perit Dial Int 25: 107–131, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szeto CC, Chow KM, Leung CB, Wong TY, Wu AK, Wang AY, Lui SF, Li PK: Clinical course of peritonitis due to Pseudomonas species complicating peritoneal dialysis: A review of 104 cases. Kidney Int 59: 2309–2315, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernardini J, Piraino B, Sorkin M: Analysis of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis-related Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Am J Med 83: 829–832, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCullagh P, Nelder JA: Generalised Linear Models, 2nd Ed., London, Chapman and Hall, 1989

- 8.Lim WH, Johnson DW, McDonald SP: Higher rate and earlier peritonitis in Aboriginal patients compared to non-Aboriginal patients with end-stage renal failure maintained on peritoneal dialysis in Australia: Analysis of ANZDATA. Nephrology (Carlton) 10: 192–197, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cass A, Cunningham J, Snelling P, Wang Z, Hoy W: End-stage renal disease in indigenous Australians: A disease of disadvantage. Ethn Dis 12: 373–378, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cass A, Gillin AG, Horvath JS: End-stage renal disease in aboriginals in New South Wales: A very different picture to the Northern Territory. Med J Aust 171: 407–410, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasgupta MK, Ulan RA, Bettcher KB, Burns V, Lam K, Dosseter JB, Costerton JW: Effect of exit site infection and peritonitis on distribution of biofilm encased adherent bacterial microcolonies (BABM) on Tenckhoff catheters in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Adv Perit Dial 2: 102–109, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dasgupta MK, Larabie M: Biofilms in peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 21[Suppl 3]: S213–S217, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]