Abstract

Asthma is considered to be more prevalent in obese subjects, and a possible causal link between these two entities has been suggested. In the present study, various observations on this relationship were reviewed, and an analysis of data obtained from the 2000 to 2001 Canadian Community Health Survey on the prevalence of self-reported asthma, medication use and allergy, according to body weight, was reported. Asthma medication use and self-reported asthma were more prevalent in the obese population, particularly in women. Mean body mass index was higher in the asthmatic population compared with the nonasthmatic population. Self-reported nonfood-related allergies were higher in the more obese subjects in the general population, but the prevalence of allergy was not different in obese asthmatic subjects compared with nonobese asthmatic subjects. Smoking did not seem to influence the relationship between asthma and body mass index. Further research should investigate the mechanisms by which obesity may influence the prevalence of asthma or asthma-like symptoms.

Keywords: Asthma, Body mass index, Obesity, Smoking

Abstract

L’asthme semble plus fréquent chez les obèses que chez les non-obèses, et un lien causal possible entre les deux états pathologiques a été avancé. Nous avons entrepris, dans la présente étude, un examen de diverses observations sur ce lien et nous faisons état d’une analyse de données tirées de l’Enquête sur la santé dans les collectivités canadiennes, réalisée de 2000 à 2001, sur la prévalence de l’asthme autodéclaré, la prise de médicaments et les allergies en fonction de l’indice de masse corporelle (IMC). L’utilisation de médicaments pour l’asthme et l’asthme autodéclaré étaient plus fréquents chez les obèses, surtout parmi les femmes. L’IMC moyen était plus élevé chez les asthmatiques que chez les non-asthmatiques. Les allergies non alimentaires autodéclarées étaient plus fréquentes chez les obèses dans la population en général, mais la prévalence des allergies chez les asthmatiques obèses ne différait pas de celle notée chez les asthmatiques non obèses. Le tabagisme ne semblait pas influer sur le lien entre l’asthme et l’IMC. Il faudrait donc faire plus de recherche sur le mécanisme par lequel l’obésité pourrait avoir une incidence sur la prévalence de l’asthme ou des symptômes asthmatiformes.

An increase in the prevalence and severity of asthma has been reported in obese subjects (1–3). However, the relationship between asthma and obesity has been variable from one study to another. In children and adults, and in both sexes, asthma seems to be generally more closely related to body mass index (BMI) in women than in men (4–6). A number of hypotheses have been proposed on how obesity could be involved in the development or an increase in severity of asthma (7,8). Obesity and asthma may be linked to a common genetic predisposition, and abnormalities of chromosomal regions linked to both entities have been observed (8). Mechanical factors could be involved (9), and we (10) recently showed an abnormal airway behaviour in nonasthmatic obese subjects. There may also be a propensity for obese subjects to develop inflammatory and/or allergic responses more easily than nonobese subjects (7,11). Finally, although obesity may predispose subjects to the development of asthma, it is possible that asthma predisposes subjects to the development of obesity (12).

To explore these relationships, we have analyzed the database from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) obtained in 2000 to 2001 (13).

METHODS

The CCHS, a cross-sectional survey, collected information related to health status between September 2000 and November 2001 (13). The survey had obtained information from 136 health regions covering all of the provinces and territories of Canada. Individuals living on Indian reserves and Crown lands, as well as institutional residents, full-time members of the Canadian Forces and residents of certain remote regions were excluded from the sampling. This survey covered approximately 98% of the Canadian population aged 12 years or older. Canada is divided into 10 provinces and three territories. Each province is divided into health regions, and each territory is designated as a single health region, totalling 136 health regions. To provide reliable estimates of these regions, a sample of 133,300 respondents was desired. The number of health regions, the targeted sample sizes by province and territory, the sampling procedures and more details from the CCHS have been published previously (13).

To access the data, we used the program Beyond 20/20 version 6.1 (Beyond 20/20 Inc, Canada) Variables DHHAGAGE and DHHA_SEX for age and sex, respectively, were chosen. HTWTAGBMI displayed a range of BMI from 14.0 kg/m2 to 57.0 kg/m2. The diagnosis of asthma was based on a positive answer to the question, “Do you have asthma?” (CCCA_031). For the purposes of the present analysis, atopy was defined as a positive answer to the question, “Do you have any other allergies?” (CCCA_021) (other than food allergies). To differentiate people who had taken asthma medications from those who had not, respondents were asked the question, “In the past 12 months, have you taken any medication for your asthma such as inhalers, nebulizers, pills, liquids or injections?” (CCCA_036). Finally, age, sex, smoking status and BMI were recorded from the corresponding sections of the database.

Analysis

Adults aged 20 to 64 years were categorized according to BMI following the recommendations of the World Health Organization and the United States National Institutes of Health: underweight (BMI less than 20 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI 20 kg/m2 or greater but less than 25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25 kg/m2 or greater but less than 30 kg/m2), obese class I (BMI 30 kg/m2 or greater but less than 35 kg/m2), obese class II (BMI 35 kg/m2 or greater but less than 40 kg/m2) and obese class III (BMI 40 kg/m2 or greater) (14,15). The weighted prevalences of weight and age were calculated using the individual sample weights provided from the database to ensure that the representative character of the results were maintained. The results are only descriptive, and no formal statistical analyses were conducted.

RESULTS

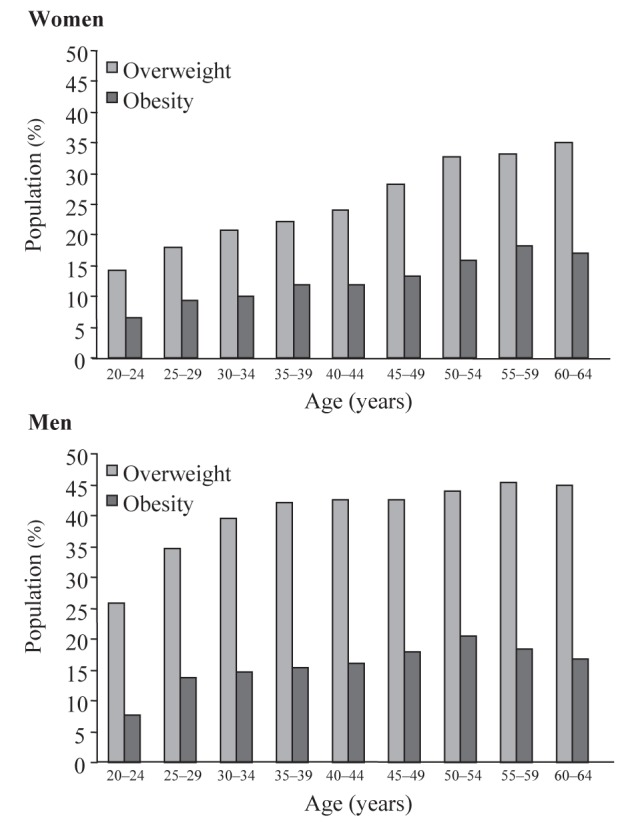

Figure 1 shows the relationships between obesity and being overweight with age and sex. In the Canadian population, being overweight and obesity had increased with age in both sexes up to the fifties, and the proportions in each age group were generally higher in men than women. Based on this sample, approximately 34% of the Canadian population are above normal weight.

Figure 1).

Relationships of obesity and being overweight to age and sex in the Canadian population. The prevalence of both obesity and being overweight increase with age, although this is more pronounced in men than in women. Normal weight: body mass index [BMI] 20 kg/m2 or greater but less than 25 kg/m2; overweight: BMI 25 kg/m2 or greater but less than 30 kg/m2; obese: BMI 30 kg/m2 or greater

Figure 2 shows self-reported asthma in Canada according to age and sex. More women than men report asthma for all age groups between 20 years and 64 years. Overall, a mean of 8% of Canadians aged 12 years or older had reported suffering from asthma. Moreover, for both sexes, the proportion of asthma had generally decreased from adolescence to the 50-year and older age group.

Figure 2).

Percentage of men and women in the Canadian population who report suffering from asthma, according to age and sex. The prevalence of asthma is higher in women than men for all age groups between 20 and 64 years

As shown in Figure 3, self-reported asthma increased with BMI. However, this increase was more evident in women with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater, while in men it seemed to increase only in those with a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or greater.

Figure 3).

Percentage of men and women from the Canadian population who report suffering from asthma, according to body mass index. An increased prevalence of asthma can be observed in obese Canadians, particularly in women

The prevalence of the Canadian population using asthma medications is shown in Figure 4. Seventy-five per cent of Canadians who had self-reported asthma mentioned that they were using asthma medications. Furthermore, the proportion of asthmatic patients using medications increased with increasing BMI, and this was more apparent in women than men.

Figure 4).

Percentage of men and women in the Canadian population who report using asthma medications, according to body mass index (percentage from the total population)

Figure 5 shows the prevalence of obesity in the asthmatic population compared with the nonasthmatic population. The prevalence of obesity (BMI 30 kg/m2 or greater) was higher in the asthmatic population.

Figure 5).

Prevalence of obesity in the asthmatic versus nonasthmatic population

Figure 6 represents the Canadian population for self-reported allergy, sex and BMI. One-quarter of the Canadian population had reported having nonfood-related allergies, and allergy had been reported more often in women and in those in obese class III. In the asthmatic population, the proportion of asthmatic patients self-reporting nonfood-related allergies was relatively constant, at approximately 60%, in each BMI group (Figure 7).

Figure 6).

Relationship between self-reported allergy (not including food allergy) and body mass index according to sex in the Canadian population

Figure 7).

Self-reported allergies (other than food allergies) according to body mass index in the Canadian asthmatic population

Finally, Figures 8 and 9 show the distribution of smoking in the general and asthmatic populations as well as the influence of BMI on this distribution. In the general population, although more ex-smokers were found in the obese groups, the distribution of BMI was relatively similar in smokers and non-smokers, even though there was much variability among groups. In the asthmatic population, the same trend is observed. Figure 9 also shows that there are fewer asthmatic subjects in the occasional (nondaily) smoking group.

Figure 8).

Self-reported asthma according to smoking habits and body mass index in the Canadian population. E Coefficient of variation between 16.6% and 33.3% (interpret with caution); F Coefficient of variation greater than 33.3% (value should be suppressed because of extreme sampling variability)

Figure 9).

Distribution of self-reported asthma among the Canadian asthmatic population according to smoking habits and body mass index. E Coefficient of variation between 16.6% and 33.3% (to be interpreted with caution); F Coefficient of variation greater than 33.3% (value should be suppressed because of extreme sampling variability)

DISCUSSION

The present overview of results of the 2000 to 2001 CCHS revealed an increased proportion of self-reported asthma and asthma medication use in obese Canadians, particularly in women. The mean BMI in the asthmatic population was higher than the mean BMI in the nonasthmatic population. Self-reported nonfood-related allergy was more often reported in the markedly obese subjects. Finally, the relationship between self-reported asthma and BMI did not seem to be influenced by smoking.

The present data analysis is mostly descriptive but provides a global estimate of obesity and contributes interesting data on the association of obesity with asthma, atopy and smoking in Canada. Our data are in keeping with previous reports, such as the analysis performed by Belanger-Ducharme and Tremblay (16) who reported that the prevalence estimates from self-reported data in a national representative sample showed that 15% of the adult population 18 years of age or older were obese, while an additional 33% were classified in the overweight category in 2003.

Our data are also in keeping with studies showing that obesity increases and allergies decrease with age, but also revealing an association between asthma and obesity (17,18). With regard to morbidly obese subjects, we had previously reported a very high prevalence of self-reported asthma in this population, suggesting that respiratory symptoms compatible with asthma or related to an asthma-like condition had affected a large number of subjects from this group (19).

Our observations also confirm that the relationship between obesity and asthma is more evident in women, although the mechanisms explaining this fact are still uncertain (20).

The prevalence of obesity decreased as BMI increased in both the asthmatic and the nonasthmatic population, suggesting that asthma generally does not significantly influence BMI.

The observation that obesity was not more prevalent in asthmatic subjects, but that asthma was more prevalent in the more obese subjects only, may suggest that, in most instances, asthma or its treatment is not responsible for obesity; it is possible, however, that the patients with more severe asthma have a higher BMI because they are more limited in exercise capacity and may take more medications that may influence weight such as oral corticosteroids. However, most asthmatics are not significantly limited in their exercise tolerance, and oral corti-costeroids are only needed in a very small number of patients or for only brief periods. Therefore, asthma medications, in general, do not seem to contribute to weight gain (21).

It has been suggested that asthma may be more prevalent in obese subjects due to a tendency to develop allergic responses or inflammatory processes (8,11,22). Although allergy had been more often reported in the markedly obese subjects, we found no significant differences in the prevalence of self-reported nonfood-related allergies among the subgroups of asthmatic subjects categorized according to BMI.

Finally, we examined the influence of smoking on asthma and obesity. There were no more asthmatic subjects among smokers than there were nonsmokers among obese subjects, as expected.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the intrinsic limitations related to the present descriptive analysis, we observed that in the Canadian population, obesity is associated with increased self-reporting of asthma and use of asthma medications. Smoking did not seem to influence the relationship between asthma and obesity. These observations support previous findings of a relationship between obesity and asthma, particularly in women, but also stress the need for more research on the significance of these findings.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Serge Simard for his help with the statistical analysis. The analyses reported in this manuscript have been performed on anonymous data obtained from the Statistics Canada public microdata files of the Canadian Community Health Survey Cycle 1.1 (2000 to 2001). The analysis and interpretation of these microdata files are the sole responsibility of the authors. This study was supported by local funds.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schaub B, von Mutius E. Obesity and asthma, what are the links? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:185–93. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000162313.64308.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akerman MJ, Calacanis CM, Madsen MK. Relationship between asthma severity and obesity. J Asthma. 2004;41:521–6. doi: 10.1081/jas-120037651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinn S. Concurrent trends in asthma and obesity. Thorax. 2005;60:3–4. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.031161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camargo CA, Jr, Weiss ST, Zhang S, Willett WC, Speizer FE. Prospective study of body mass index, weight change, and risk of adult-onset asthma in women. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2582–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.21.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hancox RJ, Milne BJ, Poulton R, et al. Sex differences in the relation between body mass index and asthma and atopy in a birth cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:440–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-623OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Dales R, Tang M, Krewski D. Obesity may increase the incidence of asthma in women but not in men: Longitudinal observations from the Canadian National Population Health Surveys. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:191–7. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tantisira KG, Weiss ST. Complex interactions in complex traits: Obesity and asthma. Thorax. 2001;56(Suppl 2):ii, 64–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss ST. Obesity: Insight into the origins of asthma. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:537–9. doi: 10.1038/ni0605-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredberg JJ. Frozen objects: Small airways, big breaths, and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:615–24. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.109429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boulet LP, Turcotte H, Boulet G, Simard B, Robichaud P. Deep inspiration avoidance and airway response to methacholine: Influence of body mass index. Can Respir J. 2005;12:371–6. doi: 10.1155/2005/517548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vieira VJ, Ronan AM, Windt MR, Tagliaferro AR. Elevated atopy in healthy obese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:504–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.3.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford ES, Mannino DM. Time trends in obesity among adults with asthma in the United States: Findings from three national surveys. J Asthma. 2005;42:91–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Statistics Canada Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) –Cycle 1.1 Ottawa, Ontario: Statistics Canada, Health Statistics Division; 2000–2001. <http://www.statcan.ca/english/concepts/health/index.htm> (Version current at April 4, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i–xii. 1–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults – The Evidence Report Obes Res 1998651S–209S.(Erratum in 1998;6:464). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belanger-Ducharme F, Tremblay A. Prevalence of obesity in Canada. Obes Rev. 2005;6:183–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: Prevalence and trends, 1960–1994. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:39–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin AJ, Landau LI, Phelan PD. Natural history of allergy in asthmatic children followed to adult life. Med J Aust. 1981;2:470–4. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1981.tb112942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simard B, Turcotte H, Marceau P, et al. Asthma and sleep apnea in patients with morbid obesity: Outcome after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1381–8. doi: 10.1381/0960892042584021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss ST, Shore S. Obesity and asthma: Directions for research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:963–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-403WS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedberg A, Rossner S. Body weight characteristics of subjects on asthma medication. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1217–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Mutius E, Schwartz J, Neas LM, Dockery D, Weiss ST. Relation of body mass index to asthma and atopy in children: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Study III. Thorax. 2001;56:835–8. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.11.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]