Practice guidelines on respiratory diseases have been published in Canada over the past two decades. Canada has led the way with regard to the production of evidence-based recommendations on optimal care, and guidelines are now available in a large variety of domains, both nationally and internationally. There was, however, until recently, no structured plan to ensure timely revision of Canadian respiratory guidelines, their rapid and effective dissemination, and particularly, no joint implementation strategy to help translate the recommendations into current care in the most effective way. Recognizing these limitations, the Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS) has therefore established a new strategy to address those needs, with a particular focus on collaborative work to more efficiently review the guidelines so that more resources are devoted to their implementation, particularly in primary care.

Among the mandates of the CTS are those of assessing the situation with regard to respiratory care in Canada and contributing to ensure appropriate and up-to-date disease management, to reduce the burden of respiratory diseases on Canadians. In collaboration with many other organizations and stakeholders, the CTS has produced various clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) in the field of respiratory health. The first Canadian Consensus Conference leading to such a guideline was held in 1989 on asthma, under the leadership of Dr Frederick E Hargreave, and was followed by the publication of updates in 1999 and 2004 (1–3). Specific guidelines have also been produced and updated on occupational asthma (4) and pediatric asthma (5). Evidenced-based management guidelines on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (6) and other conditions such as sleep apnea syndrome (7) have also been produced and disseminated, as well as various documents on standards of care in various domains of respiratory medicine.

Over the years, collaborations have been developed with international bodies, including the Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines (www.ginasthma.com) and the American College of Chest Physicians, on various aspects of guidelines production, particularly for this last, on the management of cough (8,9), occupational asthma and pulmonary vascular diseases.

The production of CPGs has improved markedly over the past few years, and Guidelines on the production of Guidelines have been developed (10). Nowadays, the majority of these documents are evidence-based and recommendations follow recommended grading systems with regard to the evidence available (11). Initial criticisms such as noninvolvement of primary care physicians, too lengthy documents, absence of hierarchy of recommendations, no cost-benefit assessment, no mention of possible adverse effects and no standardization or grading of evidence have been generally addressed. These improvements have led to significant enhancements in the quality and utility of the guideline documents.

However, integration of guideline recommendations into day-today care remains deficient, and this may be one of the reasons why disease control is still far from ideal and why many care gaps remain (12,13). This deficiency may be related to the fact that although the production of guidelines and their dissemination have much improved, much more needs to be done with regard to implementation and evaluation of their ‘real-life’ effects in various populations.

In the past few years, many large-scale initiatives have been developed to improve respiratory care in Canada. For example, the Towards Excellence in Asthma Management (TEAM) in Quebec has produced a series of multidisciplinary and targeted interventions to improve asthma management both in hospitals and in primary care, importantly combined with an evaluation of their effects on various asthma outcomes (14). The Ontario Asthma Plan is currently ongoing and includes various projects on asthma (15). Programs have been developed for COPD, in addition to numerous dissemination initiatives from the CTS COPD Committee (16).

However, these successful efforts are not widely known, and communication among the various groups and the organizations involved in the process of guideline implementation and translation of current knowledge into best care, must be improved. This is particularly true with regard to communication of successes and failures of the various implementation initiatives, and for collaborations to develop so that the best long-term strategies are established more quickly and efficiently. Currently, no such forum for effective communication of these issues exists in Canada.

Evidence has been gathered on how to develop effective knowledge transfer and guideline implementation (17). Based on solid behavioural theories and concepts, the most effective interventions to improve health behaviour have been assessed, and processes on how to structure effective implementation programs have been proposed (18). These learnings from valuable initiatives provide a good basis to establish valid implementation plans (19).

The report of a special CTS Working Group on guideline dissemination and implementation, produced in June 2006, stressed the urgent need to establish a common Canadian strategy to promote guideline implementation in this area. Following the report of the Working Group, an outline for a Canadian National Respiratory Guidelines Implementation Strategy was discussed by many interested stakeholders in Toronto on April 21, 2007. Its aims were to review the report and recommendations of the above-mentioned CTS Working Group, and to determine how the production and dissemination of guidelines by the CTS and other collaborators could follow an articulated long-term plan, thus ensuring a rapid update of these guidelines by the medical community. They also discussed a plan for guideline implementation based on current successful programs, research findings and basic principles of an effective implementation program, in addition to how to ensure appropriate evaluation of the effects of these initiatives.

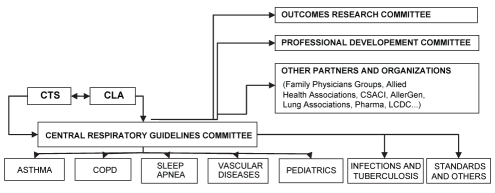

For the production of these various respiratory guidelines, the development of a central collaborative structure (Figure 1) with stable, long-term funding and meaningful terms of reference were proposed, with a specific targeted mandate. Yearly updates were suggested, with a rapid publication of changes (in relation to the dissemination process) in current guideline recommendations, in addition to additional targeted national and regional/local dissemination though various journals, media, continuing medical education events and other means. For the implementation of the guidelines, it was proposed that pilot projects, tools development, various interventions, and existing instruments either adapted or improved, could be developed. Finally, how the effect of these various initiatives on patient outcomes, health care delivery, and overall disease-related human and socioeconomic burden, could best be evaluated was considered, with a partnership with current research organizations and partners.

Figure 1).

Potential links with regard to joint guideline production, dissemination, implementation and research committees. CLA Canadian Lung Association; COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CSACI Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; CTS Canadian Thoracic Society; LCDC Laboratory Centre for Disease Control

In conclusion, there is a pressing need to improve the process of guideline production, dissemination, implementation and evaluation. Collectively, we must ensure that these efforts quickly translate into significant improvements in respiratory care, with the patient realizing the full benefits of these efforts. While the task is enormous, the results should be outstanding and serve to optimize management of respiratory disorders in Canada.

Acknowledgments

I would like to sincerely thank Virginia Forbert and Anne Van Dam for their useful comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest of Dr Louis-Philippe Boulet over the past five years include: Advisory Boards and honoraria for continuing medical education: Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Frosst, Novartis, Nycomed and Pfizer; lecture fees: 3M, Altana, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Frosst and Novartis; sponsorship for investigator-generated research: AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Frosst and Schering; research funding for participating in multicentre studies: 3M, Altana, AsthmaTx, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Dynavax, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, IVAX, MedImmune, Merck Frosst, Novartis, Roche, Schering, Topigen and Wyeth; support for the production of educational materials: AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Merck Frosst; governmental: Adviser for the Conseil du Médicament du Québec Member of the Quebec Workmen Compensation Board Respiratory Committee; organisational: Chair of the Canadian Thoracic Society Guidelines Dissemination and Implementation Committee, Chair of Canadian Thoracic Society Asthma Committee, Coleader of the therapeutics theme of the Canadian AllerGen Network of Centres of Excellence.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hargreave FE, Dolovich J, Newhouse MT. The assessment and treatment of asthma: A conference report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;85:1098–111. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(90)90056-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulet LP, Becker A, Bérubé D, Beveridge R, Ernst P. Canadian Asthma Consensus Report, 1999. Canadian Asthma Consensus Group. CMAJ. 1999;161(11 Suppl):S1–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemière C, Bai T, Balter M, Bayliff C, Becker A, Boulet LP, et al. Adult Asthma Consensus Guidelines Update 2003. Can Respir J. 2004;11(Suppl A):9A, 18A. doi: 10.1155/2004/271362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ad Hoc Committee on Occupational Asthma of the Standards Committee, Canadian Thoracic Society Occupational asthma: Recommendations for diagnosis, management and assessment of impairment. CMAJ. 1989;140:1029–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker A, Bérubé D, Chad Z, et al. Canadian Pediatric Asthma Consensus guidelines, 2003 (updated to December 2004): Introduction. CMAJ. 2005;173(6 Suppl):S12–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, et al. State of the Art Compendium: Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can Respir J. 2004;11(Suppl B):7B–59B. doi: 10.1155/2004/946769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleetham J, Avas N, Bradley D, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society guidelines: Diagnosis and treatment of sleep disordered breathing in adults. Can Respir J. 2006;13:387–92. doi: 10.1155/2006/627096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irwin RS, Boulet LP, Cloutier MM, et al. Managing cough as a defense mechanism and as a symptom. A consensus panel report of the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest. 1998;114(2 Suppl Managing):133S–81S. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.2_supplement.133s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irwin RS, Baumann MH, Boulet LP, et al. Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1 Suppl):1S–23S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.1S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidelines for Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines <http://mdm.ca/cpgsnew/cpgs/gccpg-e.htm> (Version current at August 17, 2007).

- 11.Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, et al. Grading strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in clinical guidelines: Report from an American College of Chest Physicians task force. Chest. 2006;129:174–81. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boulet LP, Becker A, Bowie D, Hernandez P, McIvor A, Rouleau M. Implementing practice guidelines: A workshop on guidelines dissemination and implementation with a focus on asthma and COPD. Can Respir J. 2006;13(Suppl A):5A–47. doi: 10.1155/2006/810978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulet LP. Asthma guidelines and outcomes. In: Adkinson NF Jr, Yunginger JW, Busse WW, Bochner BS, Holgate ST, Simons FER, editors. Middleton’s Allergy: Principles and Practice. 6th edn. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2003. pp. 1283–301. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulet LP, Thivierge RL, Amesse A, Nunes F, Francoeur S, Collet JP. Towards excellence in asthma management (TEAM): A populational disease-management model. J Asthma. 2002;39:341–50. doi: 10.1081/jas-120002292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lougheed MD, Moosa D, Finlayson S, et al. Impacts of a provincial asthma guidelines continuing medical education project: The Ontario Asthma Plan of Action’s Provider Education in Asthma Care Project. Can Respir J. 2007;14:111–7. doi: 10.1155/2007/768203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canadian Thoracic Society. Full Guidelines – CTS recommendations for management of COPD. <http://www.copdguidelines.ca/home-accueil_e.php> (Version current at August 17, 2007).

- 17.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: Effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362:1225–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis D. Clinical practice guidelines and the translation of knowledge: The science of continuing medical education. CMAJ. 2000;163:1278–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boulet LP.Improving knowledge transfer on chronic respiratory diseases: A Canadian perspective J Nutr Health Aging(In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]