Abstract

Objective

Methods producing human platelets using growth on plastic, on feeder layers, or in suspension have been described. We hypothesized that growth of hematopoietic progenitors in a 3D scaffold would enhance platelet production sans feeder layer.

Methods

We grew CD34 positively-selected human cord blood cells in surgical grade woven polyester fabric or purpose-built hydrogel scaffolds using a cocktail of cytokines.

Results

We found production of functional platelets over 10 days with 2D, 24 days with 3D scaffolds in wells, and more than 32 days in a single-pass 3D perfusion bioreactor system. Platelet numbers produced daily were higher in 3D than 2D, and much higher in the 3D perfusion bioreactor system. Platelet output increased in hydrogel scaffolds coated with thrombopoietin and/or fibronectin, although this effect was largely obviated with markedly increased production caused by changes in added cytokines. In response to thrombin, the platelets produced aggregated and displayed increased surface CD62 and CD63.

Conclusion

The use of 3D scaffolds, especially in a bioreactor-maintained milieu, may allow construction of devices for clinical platelet production without cellular feeder layers.

Introduction

A method to produce transfusable platelets in vitro would obviate many of the problems encountered with current methods to procure this life-saving blood component. Published studies of in vitro megakaryocyte or platelet production have described the use of several starting cell populations including human cord blood, embryonic stem cells, cell lines, peripheral blood progenitor cells, and marrow [1–13]. Many of these described production of megakaryocytes but not platelets. Some were performed in suspension culture or on plastic surfaces; some used feeder layers. A wide variety of added growth factors, often including thrombopoietin (TPO), stem cell factor (SCF) and Flt-3 ligand (FL), or conditioned medium has been used. Several included IL-6 or IL-11 in the last stage of the culture, and found that this increased the number of putative platelets produced [1]. Studies of platelet production per se were performed mainly to shed light on the platelet production process itself, without quantification of numbers produced. Gandhi et al, for example, described production of platelets both from a megakaryocytic cell line and from marrow in tissue culture flasks [11]. The platelets produced aggregated when exposed to appropriate agonists. Matsunaga et al published using a modified human stromal cell line to produce small amounts of functional platelets.[1] They performed their work in culture flasks, and commented that although they saw problems with scale-up, theoretically their method could produce enough platelets for a transfusion from a unit of cord blood.

Cord blood is used clinically as a source of hematopoietic progenitors. It is readily available and largely merely discarded after delivery. On the other hand, there are only a limited number of cells available in each collection. In the study reported here, we used cord blood as a source of cells for production of platelets in vitro, feeling that the ready availability outweighed the limited numbers per collection.

Early hematopoietic cells are adherent to stromal cells and extracellular matrix in vivo; this adherence influences their ability to self-renew. The earliest hematopoietic cells are found in niches along the bone in marrow spaces, relying on cell-cell interactions and the local milieu to determine their immediate fate [14]. Some aspects of the 3D niche microenvironment can be supplied by providing a feeder cell layer. These cells may supply points of contact for adherent cells, or molecules that interact with receptors on the target cell’s surface and may produce soluble chemokines or cytokines necessary for growth and survival of target cells. Several cell lines have been developed for growth of hematopoietic cells, notably the HS-5 line [15]. Primary marrow stromal cells (MSC) also have been used for this purpose, partially recapitulating the role of these cells in vivo [16, 17]. One group has reported growing marrow CD34 positive cells on MSCs, with formation of megakaryocyte colonies in serum-free medium without added cytokines [18]. We have shown that growth in a 3D matrix of nonwoven polyester fabric enhances expansion of committed progenitors, compared to growth on a 2D surface [19].

In addition to using fibrous polyester 3D scaffolds in the studies described here, we made use of purpose-built hydrogel scaffolds. Colloidal crystals can be self-assembled by sedimentation/evaporation of corresponding dispersions and then annealed to form solids [20–23]. Inverted colloidal crystals (ICC) have unique advantages as cell culture substrates, including unprecedented level of control over the 3D geometry of cellular matrixes; high porosity (74 v%void volume); exceptionally high interconnectivity – each cavity has a total of 12 neighboring ones with 12 interconnecting channels; spheroid shape of the cavities hosting cells, stimulating intercellular interactions; and simplicity of preparation. ICC scaffolds can be made without any highly specialized equipment. We postulated that utilization of this geometry constructed with biocompatible hydrogel would provide a useful milieu for marrow cell growth and platelet production, and used this as well as a woven surgical polyester fabric in the studies described here.

While Masunaga et al found that they could generate platelets using stromal support for CD34+ cell expansion into megakaryocytes, others have found the opposite. For instance, Zweegman et al found that stromal proteoglycans bound the megakaryocytopoiesis-inhibiting cytokines IL-8 and MIP-1 [24]. Supporting the use of stromal cells, Cheng et al found that they could produce platelets in culture from CD34 positive cells grown on human MSC, using serum-free medium without added growth factors [18]. Tablin and colleagues found that guinea pig proplatelets form and release platelets well from megakaryocytes on rat tail collagen gel, but are disrupted growing on Matrigel [25]. Given these findings, we elected to avoid a premade cellular feeder layer.

A number of bioreactor types have been used in hematopoietic stem cell expansion and research, including stirred tank suspension, fluidized bed, fixed bed, airlift, perfusion chamber, and hollow fiber [26]. The most frequently described, growth in (2D) static flasks or suspension, limit long term cell-cell or cell-matrix interactions. To see if a more physiologic milieu would further promote platelet production, we utilized woven polyester surgical fabric scaffold in a 3D single-pass perfusion bioreactor system. The bioreactor module is designed to allow maturing cells to settle continuously into the spent medium while immobilized parent cells are out of the direct medium flow path (Fig. 1a). The system is modular, and we have successfully used multiple bioreactor modules in parallel to facilitate cell production. This may avoid problems like those described by Matsunaga et al, in which they needed a very low concentration of early progenitors to produce large numbers of platelets in their feeder layer system [1]. Our system provides a large effective surface area, both as a result of the use of a 3D fabric scaffold and of the modular nature of the system.

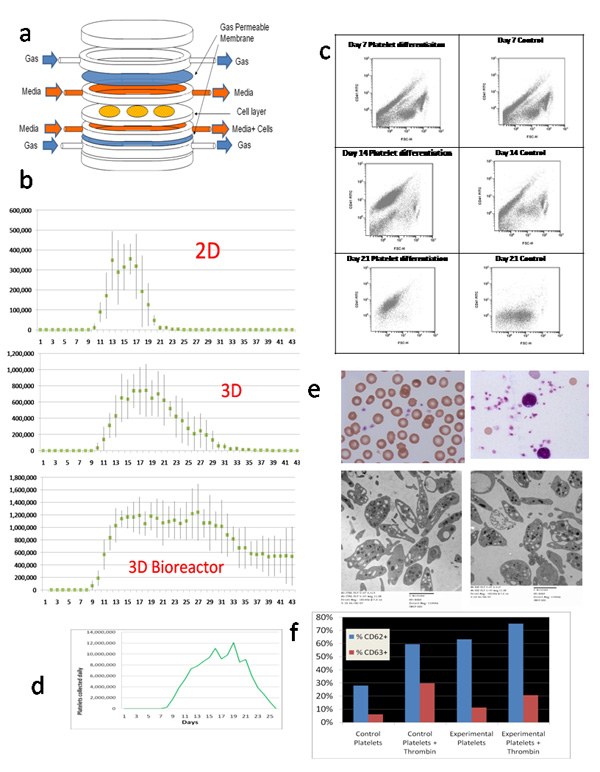

Figure 1.

(a) Exploded -view cartoon of bioreactor module. b) Comparison of daily putative platelet production using the Src kinase inhibitor differentiation medium, results of three experiments. The differentiation medium was added on day 7. (c) Flow cytometric analysis of shed cell output over time from the 3D bioreactor in Experiment 2. Differentiation medium was begun at day 7 (left column). In the control, expansion medium used through day 7 was continued (right column). Forward scatter is plotted on the horizontal axes, and CD41 fluorescence is plotted on the vertical axes. (d) The number of putative platelets produced per day using the modular bioreactor system as in (b), but for this experiment we used 6 million CD34 positively-selected cord cells that had been expanded in brief liquid culture, putting 2 million cells in each of three bioreactor modules (Table 1). (e) Representative Wright’s-stained microscopic (top) and TEM(bottom) images of platelets from the prototype modular bioreactor system (right) and fresh human cord blood platelets (left). (f) We analyzed the platelets for CD62 and CD 63 expression before and after thrombin exposure, and compared this to neonatal platelets harvested from cord blood within 24 hours of delivery, using flow cytometry.

Methods

CD34 positively-selected cord blood cell isolation

Umbilical cord blood units were obtained from normal full-term deliveries after institutional review board approval and informed consent. Light density cells were isolated from citrated cord blood using discontinuous density centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare BioSciences, Uppsala, Sweden). CD34-positive selection was conducted using a MACS Direct CD34 Progenitor Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Anaheim, California). In our laboratory this historically produces greater than 90% CD34 positive cells, as confirmed by flow cytometry. Only samples with greater than 95% viability as determined by trypan blue dye exclusion were used in further studies.

3D scaffolds

Two types of scaffolds were used. The first was 1.9 cm diameter × 1 mm depth disks of sterile surgical grade BARD polyester velour woven fabric (C.R. Bard, Inc., Humacao, Puerto Rico). This was used in both 12 well plates and the perfusion bioreactor system.

The second scaffold type was constructed from hydrogel. For manufacture of these scaffolds, colloidal crystal (CC) was used as a template for the 3D poly(acrylamide(Am)) hydrogel cell culture scaffold. The fabrication protocol of the CC resembles the process developed by Cuddihy and Kotov, and its transformation to inverted colloidal crystal (ICC) hydrogel scaffold resembles the process developed by Lee et al [21, 27]. The CC was constructed by sedimentation of soda lime glass spheres while providing agitation via sonication. To further ensure a high degree of orderliness, the sedimentation rate was retarded by focusing the spheres into a narrow channel prior to entering the mold and by the use of ethylene glycol (Sigma, St Louis, MO) as the sedimentation medium. After the thickness of the CC grew to a desired height, the CC was dried at 160°C and annealed at 700°C for 4 hours. The heat treatment caused partial melting at the surfaces, which resulted in annealing of spheres with their adjacent neighbors.

Upon the fabrication of colloidal crystal, the poly(Am) hydrogel precursor, composed of a 30 wt% acrylamide (Sigma) precursor containing 5 wt% of N,N-methylenebisacrylamide (NMBA) cross-linker, was infiltrated into the CC via centrifugation. Low viscosity of the precursor solution ensured complete infiltration in between the beads. Polymerization was initiated by adding aqueous potassium persulfate (KPS) solution (1 w/v%) at a ratio of 1:10 by volume in an oxygen-free environment. After polymerization, excess hydrogel pieces were removed and the hydrogel encapsulated CC was then immersed in a hydrofluoric acid (HF) and subsequent hydrochloric acid (HCl) bath to extract the internal glass spheres, resulting in a disc-shaped 3D ICC poly (Am) hydrogel scaffold. The ICC poly (Am) hydrogel scaffold was detoxified of the etchants by excessive rinsing with pH10 buffer, 0.1M calcium chloride solution and water followed by freeze drying.

The surfaces of ICC hydrogel scaffolds were modified through layer-by-layer deposition of positively charged 0.5 wt% poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) (PDDA, MW = 200,000, Sigma) solution and negatively charged 0.5 wt% clay platelet (average 1 nm thick and 70–150 nm in diameter, Southern Clay Products) dispersion with deionized water rinse in between the steps. Duration of each deposition and rinse was 15 minutes and a cycle of PDDA adsorption/rinse/clay adsorption/rinse process was repeated 5 times. Following the deposition of PDDA, selected scaffolds were coated separately with using 1mg/mL fibronectin in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or 10ug/mL TPO in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, then washed in PBS to remove unbound protein.

The hydrogel scaffolds, 9 to 11 mm diameter disks approximately 1 mm thick, were used in well plates. Cavities in the hydrogel were 355 to 420 um in diameter, and they interconnected with adjacent cavities by openings that averaged 10 to 15 % of the cavity diameter. They were placed on sterile polyester 1mm mesh (Textile Development Associates, Franklin Square, NY) over a conical funnel to facilitate seeding of cells into the hydrogel scaffolds by gravity filtration of cell-containing medium through the scaffold. After seeding, hydrogel scaffolds were placed in 24-well tissue culture plates and maintained in 1 mL medium at 37C humidified air 5% CO2.

3D perfusion bioreactor system

The perfusion bioreactor modules are self-contained cell support systems that facilitate medium and gas exchange over and under a cell support scaffold (Fig. 1a). The device is constructed from polycarbonate. The gas-permeable membrane is made from smooth finish fluorinated ethylene propylene (McMaster Carr, Aurora, Ohio). Three disks of woven polyester fabric, 1.9 cm diameter and 1 mm thick, used as cell scaffolds, were fixed in the center. Medium flows over and under the disks, but not through them, minimizing shear forces. Nonadherent cells produced during incubation fell into the lower medium space, from which they were be collected in the discard medium pushed out of the bioreactor module when fresh medium is added. For gas exchange, the medium is separated by a sterile smooth-finish fluorinated ethylene propylene 0.025 mm thick gas-permeable membrane (McMaster Carr Aurora, OH) barrier from a continuous flow of humidified 5% CO2 in air through the bioreactor module. Each bioreactor module has separate seeding and sampling ports allowing each module to be manipulated or removed independently of the other modules despite connections through the tubing network. In the experiments described, each module supported three BARD fabric cell scaffold disks. Bioreactor modules were run in parallel, with parallel bioreactor modules connected to a single fresh medium source.

To seed the cells into the modules, cell-containing medium was injected via a Luer lock connection. The tubing leading to and from the bioreactor module was clamped to create a cross flow of medium across the cell chamber containing the pre-placed fabric scaffold. The cells were then injected into the bioreactor module from the syringe such that the medium flow was through the matrix from top to bottom, resulting in trapping of cells within the scaffold. Cells were then permitted to adhere to the scaffold for 24–72 hours before the tubing clamps were removed and regular cross flow of medium resumed.

Medium exchange and cell harvests were accomplished simultaneously in the single pass bioreactor module. Daily, medium (3mL) containing non-adherent cells were withdrawn from the bioreactor as fresh medium entered the module from the medium supply. For platelet function studies, a syringe containing 35 mL of glucose-based platelet storage medium, as previously described by Holme et al, was attached to the harvest port of the bioreactor module [28]. Three mL of platelet differentiation medium containing shed cells was withdrawn into the syringe.

Medium and growth factors, experimental design

CD34-enriched cells were initially expanded in liquid culture at 37C humidified air mixed with 5% CO2 for 48–72 hours in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM; Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) expansion medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FCS; JRH Bio Sciences Lenexa, Kansas), 50 ng/ml SCF, 50 ng/ml FL, 10 ng/ml TPO, and 10 ng/ml IL-6. All growth factors were from R and D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

After the liquid culture expanded cells were seeded separately into each type of support scaffold. The cells were maintained for 7 days with daily medium changes after 48 hours in hematopoietic progenitor maintenance medium containing IMDM, 10% FCS, 10% horse serum (JRH Bio Sciences), 0.25uM hydrocortisone, 10ng/mL TPO, and 25ng/mL FL. All additional medium additives and growth factors were from R and D Systems, Minneapolis. After 7 days, the medium was changed to differentiation medium to promote megakaryocyte and platelet production (Src differentiation medium) that consisted of IMDM, 10% FBS, 30ng/ml TPO, 1ng/ml SCF, 7.5 ng/ml IL-6, 13.5 ng/ml IL-9, and 2.5 uM SU6656 (Sigma), a Src kinase inhibitor.

This regime was used to compare incubation in tissue culture wells, in polyester fibrous scaffolds in wells, and in polyester fibrous scaffolds in the bioreactor system. Each experiment was performed using a unit of cord blood; approximately two million CD34 positively-selected cells were used for each of the three conditions. One aliquot was cultured at the bottom of 6 tissue culture wells in a 12 well plate, one was cultured in six 1.9 cm diameter × 1 mm woven polyester scaffold maintained in 6 tissue culture wells in a 12 well plate, and the last was cultured in the 3D single pass perfusion bioreactor, using two modules, containing a total of 6 woven polyester scaffolds, connected in parallel to gas and medium supplies, and maintained at 37 C.

To determine the possible effect of increasing IL-6 and adding IL-11, one experiment was performed using IMDM containing 10% FBS, 1% bovine serum albumen, 25 ng/mL TPO, 25 ng/mL IL-3, 50 ng/mL IL-6, and 10 ng/mL IL-11 as differentiation medium (IL-6,-11 medium).

One experiment to compare effects of different protein coatings’ was performed in hydrogel scaffolds in tissue culture wells using Src differentiation medium. Then, to determine the possible effect of more IL-6 and added IL-11 in the protein-coated hydrogel scaffolds, another experiment using platelet differentiation medium containing IL-11 and a higher dose of IL-6 was performed. Src differentiation medium was used from day 7 to 14, when the differentiation medium was switched to IL-6,-11 medium on day 14.

Imaging

Light microscopy was performed on cells harvested from culture conditions on an Axioskop 2 Zeiss microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) utilizing the Axiocam imaging system. Wright’s-stained Cytospin (Shandon, Pittsburgh, PA) preparations were examined for morphology. For fluorescent studies of hydrogel scaffold sections, wedges were cut from whole scaffolds on day 32 following cell seeding. The hydrogel scaffold sections were incubated with FITC-labeled anti-CD41 or control IgG FITC antibodies, washed in PBS and placed on glass slides under Coverwell imaging chamber gaskets (Molecular Probes, Eugene OR).

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), an enriched platelet suspension was fixed in a 10:1 solution of phosphate buffered saline and 2.5% glutaraldehyde, pH 7.4. Following fixation, the platelet suspension was transferred to 2% liquefied agarose at 45C. The agarose block containing the visible platelet pellet was then processed for TEM following the methods detailed by McLean et al with the exception that for fixation, an Epon-ethanol mixture was used instead of Spurr [29]. Studies were performed using a FEI Technai G2 Spirit Transmission Electron Microscope (Eindhoven, Netherlands).

Flow cytometry and aggregation studies

Cells for flow cytometric analysis were washed in Ca++/Mg++ free Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline to remove culture medium and labeled with FITC/PE conjugated antibodies (Immunotech, Marseille, France) for surface antigens, including those for CD34, CD41, CD62, and CD63. Excess antibody was removed by washing, and the fluorescent cell analysis was performed on a BD FACSCalibur System flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For comparison neonatal platelets were isolated from citrated cord blood by 120 × g centrifugation for 15 minutes at room temperature. Neonatal platelets were then washed and labeled as described for experimentally-produced platelets.

To determine the functional properties of platelets harvested from 2D, 3D and 3D perfusion bioreactor growth conditions, as well as hydrogel scaffolds, harvested platelets were collected, washed, and resuspended in 35mL glucose storage buffer, incubated with or without 1.0U/mL thrombin for 10 min at 37C, and observed for aggregation using phase microscopy [28].

To detect platelet activation antigens CD62 and CD63, platelets were isolated and enriched as previously described. The platelet-rich portion was then resuspended in Ca++/Mg++ free Dulbecco’s PBS and incubated with or without 1.0U/mL thrombin for 10 min at 37C. Platelet activation surface antigens CD62 and CD63 were measured by flow cytometry before and after exposure to thrombin.

Results

Comparison of platelet production in 2D, 3D, and bioreactor

CD34 positively-selected cord cells were expanded for 48 to 72 hours in liquid culture. This increased the number of cells from about 2 million to about 15 million, and increased the number of CD34+ cells 4 to 5 fold. Following this, CD34 positively-selected cord cells from the same donor were divided in equal numbers among three conditions. Cells were further incubated in wells (2D), introduced into fabric scaffolds (3D), or infused into perfusion bioreactor modules containing identical scaffolds (3D bioreactor; Table 1). Daily, old medium was removed and fresh medium was added. Cells in the old medium from each condition were harvested by centrifugation, counted, and further characterized. We connected two identical bioreactor modules in parallel for these experiments. At 7 days, growth factors were changed to IL-6, IL-9, SCF, TPO, and SU6656, a Src kinase inhibitor. We used a modification of the method described by Gandhi et al for 2D culture [11]. We replaced IL-3 with IL-9 based on the work of Cortin et al, who carefully compared a large number of cytokine combinations for their megakaryocyte and platelet production potential, and that of Fujiki et al [30, 31]. In three identical experiments, in tissue culture wells (2D), 2.3, 1.8, and 1.7 × 106 morphologic platelets were produced from day 12 to 25; in 3D scaffolds in wells (with a total of 6 disks per experiment), 10, 6.9, and 9.3 × 106 from day 12 to 37; and in 3D scaffolds in the modular perfusion bioreactor, 31, 31, and 36 × 106 from day 8 to day 40 (Fig. 1b). When normalized to number of platelets produced per CD34 positively-selected expanded cord blood cell, the 3D bioreactor produced statistically significantly higher yield per starting cell compared to either 2D or 3D production in wells.

Table 1.

| Table 1a: Experimental summary. Platelet yields from start of CD34 selection (cell and platelet counts in millions). | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | After CD34+ Column ×106 | After liquid expansion ×106 | Starting cell number per condition ×106 | Platelets from 2D ×106 (number per starting cell) | Platelets from 3D ×106 (number per starting cell) | Number of bioreactor modules/ Number of disks* | Platelets from 3D Bioreactor ×106 (number per starting cell***) |

| 1 Src differentiation medium | 1.8 | 14 | 2.2 | 2.3 (1.0) | 10.5 (4.8) | 2/6 | 31.3 (14.2) |

| 2 Src differentiation medium | 1.5 | 18 | 2.8 | 1.7(0.61) | 6.9 (2.5) | 2/6 | 30.7 (10.9) |

| 3 Src differentiation medium | 2.1 | 22 | 3.5 | 2.8(0.80) | 9.3 (2.6) | 2/6 | 36.2 (10.3) |

| 1 | |||||||

| IL-6, -11 medium | 1.3 | 12 | 6 | ND | ND | 4/12 | 117.7 (19.6) |

| Coated hydrogel scaffolds– Src differentiation medium | 1.5 | 11 | 2 | ND | 4.4 ** (2.2**) |

ND | ND |

| Coated hydrogel scaffolds 3 stage | 2.1 | 14 | 8 | ND | 38.1** (4.7**) |

ND | ND |

| Table 1b: Coated hydrogel scaffold experiments. Platelet yields from start of CD34 selection (cell and platelet counts in millions). | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | After CD34+ column | After liquid expansion | Starting number | Clay Coated | FN Coated | TPO Coated | FN+TPO Coated | Total Platelets from all 4 conditions |

| Coated hydrogel scaffolds--Src differentiation medium | 1.5 | 11 | 2 (0.5 per scaffold, 1 scaffold disk per condition) |

0.9 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 4.4 (2.2 per starting cell) |

| Coated hydrogel scaffolds--3 stage | 2.1 | 14 | 8 (0.5 per scaffold, 4 scaffold disks per condition) |

9.3 (2.3 per scaffold) |

8.1 (2.0 per scaffold) |

10.2 (2.5 per scaffold) |

10.5 (2.6 per scaffold) |

38.1 (9.5 per 4 scaffolds) (4.7 per starting cell) |

Number of disks applies to both the 3D and the 3D Bioreactor conditions. Six wells in 12 well plates were used for eache 2D condition.

Total for 4 conditions—see Table 1b

For experiments 1 to 3, p<.05 for 3D Bioreactor vs. 2D or 3D using paired t-test. Paired T-test for 2D vs 3D—normalized to platelets per starting cell p=.062 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Hydrogel scaffolds were 15 mm diameter disks approximately 2 mm in thickness.

Platelet production scale-up

When we increased the dose of IL-6 and added IL-11, as suggested by the work of De Bruyn et al, we found a considerable increase in length of platelet production and numbers produced daily (Table 1 and Fig. 1d) [3]. For this experiment we used 6 million CD34 positively-selected cord cells that had been expanded in brief liquid culture, putting 2 million cells in each of three bioreactor modules (Table 1). Even considering the increased starting numbers over the previous experiments, the number of platelets produced per day was increased dramatically over the previously-used cytokine combination. Approximately twice the number of putative platelets per expanded CD34 positively-selected cell that we observed with Src differentiation medium was produced.

Platelet evaluation

Compound microscopy of Wright-stained smears and Cytospins showed a heterogeneous mixture of normal and atypically-shaped and –sized platelets (Fig. 1e). TEMs showed the presence of alpha and dense granules, mitochondria, open cannicular elements, and circumferential microtubules similar to that seen with concurrent fresh cord blood platelets, although there were somewhat more microparticles, ghosts, and abnormally-shaped and -sized platelets, with some degranulation. Serial flow cytometry in one experiment showed decreasing contamination of CD41 negative particles as CD41 positive small particles increased (Fig. 1c). The day 7 results for the platelet differentiation medium and the control medium were identical, as expected. At 14 days, a large population of small (low forward scatter) CD41 positive particles were recorded in the sample from the differentiation bioreactor; these were presumably platelets. There was also a significant population of small particles that were not CD41 positive, probably cellular debris. This debris almost disappeared at the day 21 and day 28 time points, while the small-sized CD41 positive population persisted.

The platelets collected aggregated in response to thrombin, as did neonatal control platelets. We analyzed the platelets for CD62 and CD 63 expression before and after thrombin exposure, and compared this to neonatal platelets harvested from cord blood within 24 hours of delivery, using flow cytometry (Fig. 1f). The bioreactor-produced platelets showed considerable CD62 and CD63 activation above that seen with cord blood platelets. Thrombin activation increased the expression of both markers of platelet activation above the baseline expression.

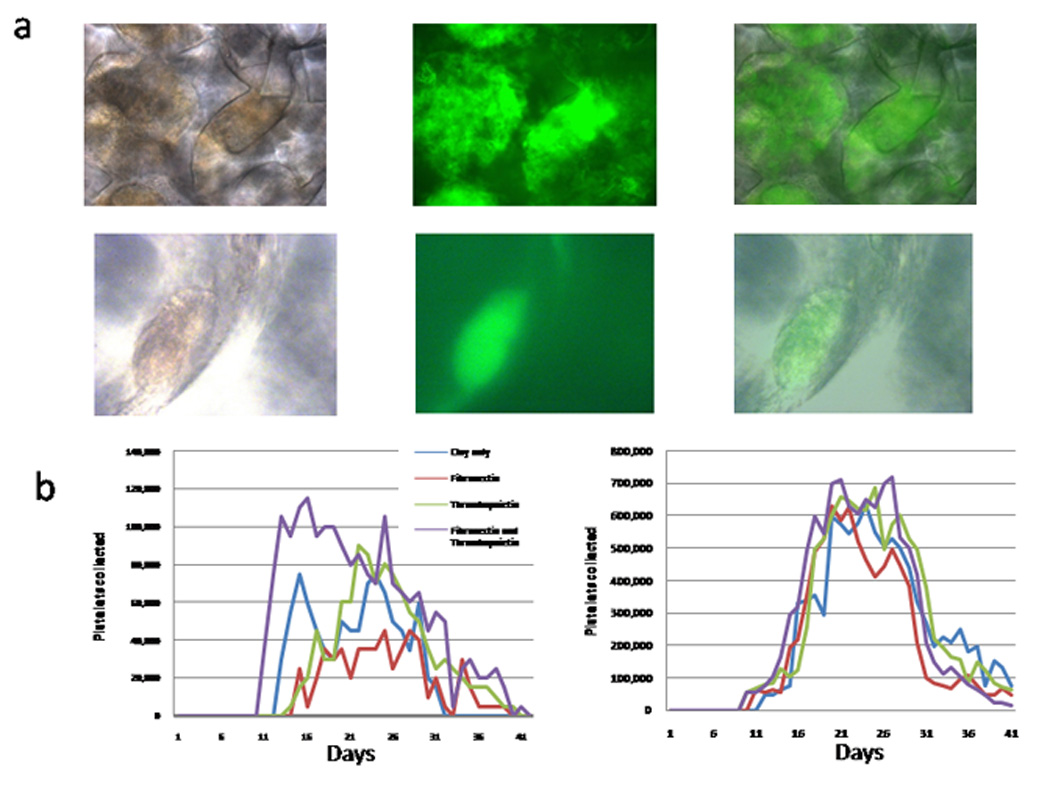

Effect of protein coating scaffold

To see the potential effect of embedded proteins in 3D, we used hydrogel scaffolds coated with clay without embedded protein or decorated with fibronectin and / or thrombopoietin, in tissue culture wells (Fig. 2 and Table 1b). The results suggested fibronectin and TPO increased the amount and duration of platelet production, over plain clay coating alone (Fig. 2b). Increasing IL-6 and adding IL-11 increased platelet production, and the effect of protein coatings was largely lost (Fig. 2b). Total production normalized to starting expanded CD34 positively-selected cells approximately doubled (Table 1).

Figure 2.

(a) Phase (first column), fluorescent (second column) and combined (third column) microscopic images of cells growing in hydrogel scaffold. Cells are stained with FITC-labeled antiCD41. The top row is a low power view that shows the shape of the interconnecting cavities in the scaffold and the large extent of megakaryocyte and platelet production in the scaffold. The lower row is a high power view of an isolated megakaryocyte on the wall of a cavity. (b) Daily putative platelet production in hydrogel scaffolds in wells: effect of protein coating. Results are shown for Src kinase differentiation medium (left graph), and for IL-6,-11 differentiation medium after 7 days of Src differentiation medium (right graph).

Discussion

Although no one has yet reported production of platelets in numbers near that required for transfusion in humans, others have published some beginning progress in this area [1–13]. Most were performed in suspension or 2D flask culture; some used feeder layers. A wide variety of added growth factors or, for earlier studies, conditioned medium was used to support the cultures. Common medium cell growth additives include TPO, SCF and FL, sometimes with the addition of IL-6 or IL-11. None of these cited publications used a 3D scaffold to support the cells.

In the report by Gandhi et al, which utilized growth in tissue culture flasks (2D), the number of platelets produced was not given [11]. They used a Src kinase inhibitor, in addition to the cytokines IL3, IL6, SCF and TPO to enhance megakaryocyte development. In our study, we used the method described in that paper, with slight modification, to produce platelets in our 3D and 3D bioreactor systems. Our modification was to replace IL-3 with IL-9, based on the work of Cortin et al, who carefully compared a large number of cytokine combinations for their megakaryocyte and platelet production potential, and that of Fujiki et al [30, 31]. In our 3D bioreactor system, when we increased the dose of IL-6 and added IL-11, as suggested by the work of De Bruin et al, we found increased putative platelet production [3].

Matsunaga and colleagues published results suggesting that the number of platelets that can be produced in vitro may be enough for clinical platelet transfusion [1]. They expanded cord blood CD34 positive cells using SCF, FL, and TPO on genetically modified human marrow stroma (carrying an inserted gene for telomerase). After 14 days, growth factors were switched to SCF, TPO, FL and IL-11 for 14 days, to promote megakaryocyte formation. Then the cells were incubated without the stromal cells for another 7 days in these same growth factors to allow the megakaryocytes to mature and produce platelets. Although the batch size was a fraction of that needed to make platelets for transfusion, they calculated that with a single unit of cord blood they could make platelets in numbers equivalent to 2 to 4 units of donor platelets made from whole blood, or 20 to 60 percent of a unit of apheresis platelets. They found normal morphology by TEM and normal response to ADP and fibrinogen, both by aggregation and by appearance of P-selectin and activated IIb/IIIa on the surface of the cells. The incubations were performed in 75 cm2 tissue culture flasks. The authors reported trying various other cytokine combinations at each stage but the ones listed above seemed to be the best for platelet production.

In the research presented here, we avoided the use of feeder cells. Some aspects of the 3D niche microenvironment can be supplied in a culture system in which a feeder cell layer is used. This feeder layer, often cell lines or MSCs, may supply points of contact for adherent cells, molecules that interact with receptors on the target cell’s surface, or the opposite, and may also produce soluble chemokines or cytokines necessary for the target cells growth and survival [15][[16, 17]. Osiris Therapeutics, Inc., has reported successfully growing marrow CD34 positive cells on MSCs, with formation of megakaryocyte colonies in serum-free medium without added cytokines [18]. Because of the difficulty of obtaining and maintaining a feeder layer in a large scale system, we sought, successfully, to determine whether we could produce functional platelets using a feeder-free 3D culture system.

We demonstrated marked improvement in platelet production when 3D cell-scaffold constructs were created and grown in a 3D modular single-pass perfusion bioreactor system. Several types of bioreactors have been described for growth of hematopoietic cells. The most simple, suspension or 2D adherent-cell cultures, allow minimum cell-cell contact. Most flow systems such as packed bed reactors produce significant shear forces on the growing cells [32–34]. The Aastrom RepliCell, initially introduced to expand marrow-derived progenitors, uses a single pass 2D system(e.g.,[35]). Other 3-dimensional culture methods for human cells that utilize some form of bioreactor include a tantalum-coated porous biomaterial (Cytomatrix) to culture and expand hematopoietic progenitor cells from bone marrow for up to 6 weeks and umbilical cord blood CD34+ cells for up to 2 weeks [36, 37]. Banu, et al, successfully cultured CD34+ cells from human bone marrow on a porous three-dimensional biomatrix (Cellfoam™) for up to 6 weeks [38]. Zhao and Ma reported the used PET matrix scaffolds in a bioreactor device to culture human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for a period of 40 days [39]. Braccini, et al, also reported expansion of MSCs in a 3D scaffold-based bioreactor system, in addition to co-culture of hematopoietic progenitor cells [40]. Our bioreactor system is purpose-built for hematopoietic culture; it allows continuous collection of nonadherent cells. At the same time, it allows independent control of medium and gas flow, as well as a variety of medium utilization methods. The system as described here uses a discontinuous (every 24h) single-pass scheme, but it can be configured for continuous or pulsed flow with or without automatic recycling of the output medium. The environment engendered by the bioreactor module, even with the limited (once per 24 hours) flow, allows nutrient, waste, and gas exchange above and below the 3D scaffold; we believe this accounts for the greatly increased platelet production in the bioreactor system.

To test function, we performed aggregation studies using a method for small numbers of platelets [28]. The platelets showed a similar thrombin response to that seen in neonatal platelets, both in our studies and in that of others [41, 42]. There was also a measurable response to thrombin using antibodies to CD62 and CD63 by flow cytometry. The flow studies, while showing an increment in activation with thrombin, also showed that these platelets were activated in the absence of added thrombin. Several possible explanations, including activation on contact with portions of the bioreactor system flow path or activation by the cytokine-containing differentiation medium, are possible. We also noted somewhat deranged morphology compared to similarly-prepared neonatal platelets in both Wright’s stained preparations and with TEM. We think that the activation sans added agonists and the abnormal morphology can be remedied by several future changes in the system, notably by using continuous medium flow into the bioreactor modules with resulting continuous collection of shed platelets, and by modifying the surfaces of the bioreactor system and scaffolds.

To test platelet formation in the presence or absence of adherent TPO or fibronectin. we used poly(Am) hydrogel as the substrate material for an inverted crystalloid scaffold, chosen for its biocompatibility, mechanical strength and transparency. Mechanical rigidity resulted in a firm ICC structure and transparency allowed facile optical analysis. We modified the hydrogel surface using by layer-by-layer deposition of positively charged 0.5 wt% PDDA solution and negatively charged 0.5 wt% clay platelet dispersion.[43] The LBL deposition of nano-structured clay platelet and PDDA increased nano-scale roughness and created surface charge and stiff film, which worked in concert, along with adhered proteins, to bind and stimulate cells. We knew from the literature that megakaryocytes and CFU-MK bind to fibronectin and that TPO promotes early hematopoietic cell and megakaryocyte adherence to fibronectin [44]. We found that with the combination of both TPO and fibronectin, utilizing the SRC kinase inhibitor medium, platelet production lasted longer at a higher level vs. only one or the other or neither. On the other hand, when we maximized platelet production using IL-6 and IL-11, little increase was seen in platelet numbers produced with either or both coating proteins. Our hypothesis is that the TPO has both a stimulating and a binding effect in our system, and that fibronectin also binds both progenitors and megakaryocytes during hematopoiesis in the system. The need for the bound proteins to increase platelet production is overcome by increasing fluid-phase IL-6 and adding IL-11.

The current results show continuous prolonged production of platelets using a 3D single-pass intermittent-flow perfusion bioreactor system, markedly more than with conventional 2D culture. While we expected to produce platelets with the system, its ability to produce them over a long period of time (several weeks) was unexpected. It appears that the 3D milieu engendered by the scaffolds we have used, especially when used with our modular bioreactor system, allows asynchronous production of platelet progenitors and precursors for prolonged periods. Even so, the number of platelets produced falls far short of the number needed for transfusion. Future improvements to increase yield include adoption of methods to increase the number of early progenitors from cord blood; longer periods of continuous perfusion, with or without medium recirculation; and alterations in scaffold surface makeup and design.

More than two million platelet transfusions are given in the US annually. The brief storage time of platelets, 5 to 7 days, often creates shortages in times of emergency and environmental crisis. These and other difficulties could be overcome with an in vitro platelet production system. The work presented here may provide a foundation for future development of such a clinical production system, in addition to creating an in vitro model of megakaryocytopoiesis and thrombopoiesis that can be used to study these processes and the effect of drugs and disease.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Center for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine (Tech 06-063) through the Biomedical Research and Commercialization Program, a component of the Third Frontier Program of Ohio (LCL), NIH 5R01EB007350-02 (NAK), and NIH R21HL072088 (LCL). Flow cytometry was performed at the University Cell Analysis and Sorting Core, a joint venture between The Comprehensive Cancer Center and The Davis Heart & Lung Research Institute, and electron microscopy was performed at the Campus Microscopy and Imaging Facility, both at The Ohio State University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Matsunaga TTI, Kobune M, Kawano Y, Tanaka M, Kuribayashi K, Iyama S, Sato T, Sato Y, Takimoto R, Takayama T, Kato J, Ninomiya T, Hamada H, Niitsu Y. Ex Vivo Large-Scale Generation of Human Platelets from Cord Blood CD34+ Cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2877–2887. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu YLT, Fan X, Ma X, Cui Z. Ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem cells derived from umbilical cord blood in rotating wall vessel. J Biotechnol. 2006;124:592–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Bruyn C, Delforge A, Martiat P, Bron D. Ex Vivo Expansion of Megakaryocyte Progenitor Cells: Cord Blood Versus Mobilized Peripheral Blood. Stem Cells and Development. 2005;14:415–424. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao CLCI, Hsieh TB, Hwang SM. A systematic strategy to optimize ex vivo expansion medium for human hematopoietic stem cells derived from umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:720–727. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shim MHHA, Blake N, Drachman JG, Reems JA. Gene expression profile of primary human CD34+CD38lo cells differentiating along the megakaryocyte lineage. Exp Hematol. 2004;32:638–648. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawano YKM, Yamaguchi M, Nakamura K, Ito Y, Sasaki K, Takahashi S, Nakamura T, Chiba H, Sato T, Matsunaga T, Azuma H, Ikebuchi K, Ikeda H, Kato J, Niitsu Y, Hamada H. Ex vivo expansion of human umbilical cord hematopoietic progenitor cells using a coculture system with human telomerase catalytic subunit (hTERT)-transfected human stromal cells. Blood. 2003;101:532–540. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schipper LFBA, Reniers N, Melief CJ, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Differential maturation of megakaryocyte progenitor cells from cord blood and mobilized peripheral blood. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:324–330. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabri SJ-PM, Bertoglio J, Farndale RW, Mas VM, Debili N, Vainchenker W. Differential regulation of actin stress fiber assembly and proplatelet formation by alpha2beta1 integrin and GPVI in human megakaryocytes. Blood. 2004;104:3117–3125. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujimoto TT, Kohata S, Suzuki H, Miyazaki H, Fujimura K. Production of functional platelets by differentiated embryonic stem (ES) cells in vitro. Blood. 2003;102:4044–4051. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eto K, Murphy R, Kerrigan SW, et al. Megakaryocytes derived from embryonic stem cells implicate CalDAG-GEFI in integrin signaling. PNAS. 2002;99:12819–12824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202380099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandhi MJ, Drachman JG, Reems JA, Thorning D, Lannutti BJ. A novel strategy for generating platelet-like fragments from megakaryocytic cell lines and human progenitor cells. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2005;35:70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazur EMBD, Newton JL, Cohen JL, Charland C, Sohl PA, Narendran A. Isolation of large numbers of enriched human megakaryocytes from liquid cultures of normal peripheral blood progenitor cells. Blood. 1990;76:1771–1782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaushansky KBV, Lin N, Jorgensen MJ, McCarty J, Fox N, Zucker-Franklin D, Lofton-Day C. Thrombopoietin, the Mp1 ligand, is essential for full megakaryocyte development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3234–3238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams GB, Scadden DT. The hematopoietic stem cell in its place. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:333–337. doi: 10.1038/ni1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roecklein BA, Torok-Storb B. Functionally distinct human marrow stromal cell lines immortalized by transduction with the human papilloma virus E6/E7 genes. Blood. 1995;85:997–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kadereit S, Deeds LS, Haynesworth SE, et al. Expansion of LTC-ICs and maintenance of p21 and BCL-2 expression in cord blood CD34(+)/CD38(−) early progenitors cultured over human MSCs as a feeder layer. Stem Cells. 2002;20:573–582. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.20-6-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng L, Hammond H, Ye Z, Zhan X, Dravid G. Human adult marrow cells support prolonged expansion of human embryonic stem cells in culture. Stem Cells. 2003;21:131–142. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-2-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng L, Qasba P, Vanguri P, Thiede MA. Human mesenchymal stem cells support megakaryocyte and pro-platelet formation from CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitor cells. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:58–69. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200007)184:1<58::AID-JCP6>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Ma T, Kniss DA, Yang ST, Lasky LC. Human cord cell hematopoiesis in three-dimensional nonwoven fibrous matrices: in vitro simulation of the marrow microenvironment. J HematotherStem Cell Res. 2001;10:355–368. doi: 10.1089/152581601750288966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotov N, Liu Y, Wang S, et al. Inverted Colloidal Crystals as 3D Cell Scaffolds Langmuir. 2004;20:7887–7892. doi: 10.1021/la049958o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J, Shanbhag S, Kotov NA. Inverted colloidal crystal scaffolds as three dimensional microenvironments to study cell interactions in co-cultures. JMaterRes. 2006;16:3558–3564. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shanbhag S, Lee JW, Kotov N. Diffusion in three-dimensionally ordered scaffolds with inverted colloidal crystal geometry. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5581–5585. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Wang S, Eghtedari M, Motamedi M, Kotov NA. Inverted-colloidal-crystal hydrogel matrices as three-dimensional cell scaffolds. Advanced Functional Materials. 2005;15:725–731. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zweegman SVDBJ, Mus AM, Kessler FL, Janssen JJ, Netelenbos T, Huijgens PC, Drager AM. Bone marrow stromal proteoglycans regulate megakaryocytic differentiation of human progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 2004;299:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tablin FCM, Leven RM. Blood platelet formation in vitro. The role of the cytoskeleton in megakaryocyte fragmentation. J Cell Sci. 1990;97(Pt 1):59–70. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cabrita GJM, Ferreira BS, Lobato de Silva C, Goncalves R, Almeida-Porada G, Cabral JMS. Hematopoietic stem cells: from the bone to the bioreactor. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21:233–240. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(03)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuddihy JM, Kotov NA. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) bone scaffolds with inverted colloidal crystal geometry. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2008 doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holme. Improved in vivo and in vitro viability of platelet concentrates stored for seven days in a platelet additive solution. Br J Haematol. 1987;66:233–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1987.tb01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLean MRLA, Garancis JC, Hause LL. A method for the preparation of platelets for transmission electron microscopy. Stain Technol. 1982;57:113–116. doi: 10.3109/10520298209066538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cortin V, Garnier A, Pineault N, Lemieux R, Boyer L, Proulx C. Efficient in vitro megakaryocyte maturation using cytokine cocktails optimized by statistical experimental design. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:1182–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujiki. Role of human interleukin-9 as a megakaryocyte potentiator in culture. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:1373–1380. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00966-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mantalaris A, Keng P, Bourne P, Chang AY, Wu JH. Engineering a human bone marrow model: a case study on ex vivo erythropoiesis. Biotechnol Prog. 1998;14:126–133. doi: 10.1021/bp970136+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meissner P, Schröder B, Herfurth C, Biselli M. Development of a fixed bed bioreactor for the expansion of human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Cytotechnology. 1999;30:227–234. doi: 10.1023/A:1008085932764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jelinek N, Schmidt S, Hilbert U, Thoma S, Biselli M, Wandrey C. Novel Bioreactors for the ex vivo Cultivation of Hematopoietic Cells. Enginnering in Life Sciences. 2002;2:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaroscak J, Goltry K, Smith A, et al. Augmentation of umbilical cord blood (UCB) transplantation with ex vivo-expanded UCB cells: results of a phase 1 trial using the AastromReplicell System. Blood. 2003;101:5061–5067. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bagley J, Rosenzweig M, Marks DF, Pykett MJ. Extended culture of multipotent hematopoietic progenitors without cytokine augmentation in a novel three-dimensional device. Experimental Hematology. 1999;27:496–504. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(98)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ehring B, Biber K, Upton TM, Plosky D, Pykett M, Rosenzweig M. Expansion of HPCs from cord blood in a novel 3D matrix. Cytotherapy. 2003;5:490–499. doi: 10.1080/14653240310003585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banu N, Rosenzweig M, Kim H, Bagley J, Pykett M. Cytokine-augmented culture of haematopoietic progenitor cells in a novel three-dimensional cell growth matrix. Cytokine. 2001;13:349–358. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao F, Ma T. Perfusion bioreactor system for human mesenchymal stem cell tissue engineering: dynamic cell seeding and construct development. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;91:482–493. doi: 10.1002/bit.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braccini A, Wendt D, Jaquiery C, et al. Three-dimensional perfusion culture of human bone marrow cells and generation of osteoinductive grafts. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1066–1072. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Israels SJRM, Michelson AD. Neonatal platelet function. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2003;29:363–372. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Israels. Impaired signal transduction in neonatal platelets. Pediatr Res. 1999;45:687–691. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199905010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang Z, Kotov NA, Magonov S, Ozturk B. Nanostructured artificial nacre. Nature Materials. 2003;2:413–418. doi: 10.1038/nmat906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Molla A, Mossuz P, Berthier R. Extracellular matrix receptors and the differentiation of human megakaryocytes in vitro. Leuk Lymphoma. 1999;33:15–23. doi: 10.3109/10428199909093721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]