Abstract

Most foster parents in the United States are required to participate in training, yet no empirical support exists for the training’s effectiveness. During the past two decades, high-quality clinical trials have documented that parent management training (PMT) programs produce positive outcomes for children and families in clinical and school settings; yet, these advances have not transferred to foster/kinship parents. Here, we describe a randomized control trial testing the effectiveness of a PMT-based treatment with 700 foster/kinship parents in San Diego County. The collaborative processes to engage stakeholders, the strategies for involving parents, and the results of two levels of developer involvement in training and supervision on child behavioral outcomes are also described.

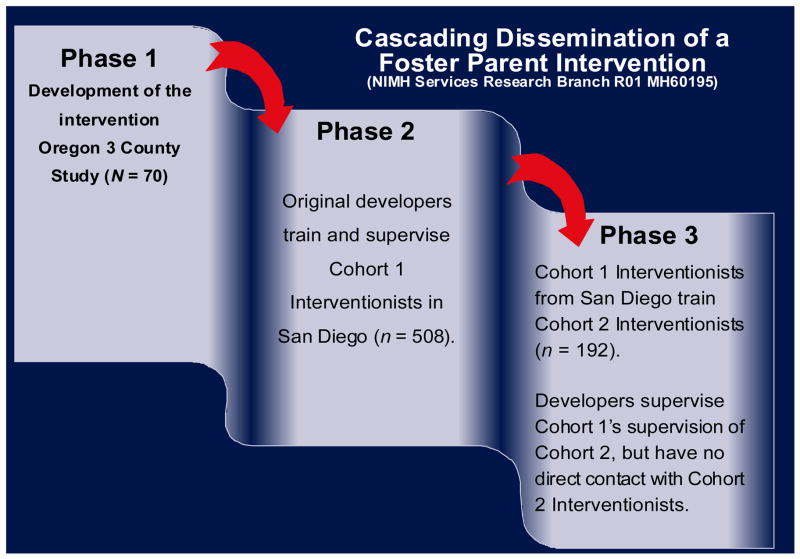

In all but two states, child welfare systems require that foster parents participate in some form of training to prepare them to deal with the children placed in their homes; however, little is known about the effectiveness of this training (Dorsey, Farmer, Barth, Greene, Reid, & Landsverk, 2008). In this paper, we describe a study that tested the transferability of a research-based parent management training (PMT) with foster parents in San Diego County. The study enrolled 700 foster and kinship families and randomly assigned them to the PMT or control conditions. The two overarching aims of the study were (a) to test whether participation in the intervention strengthened foster parents’ parenting skills and whether improved skills resulted in fewer child behavioral and emotional problems and increased permanency (e.g., fewer disruptions, increased stability, more frequent reunifications with biological/adoptive families) and (b) to compare the effects on child outcomes obtained during two phases of implementation (i.e., with and without the direct involvement of the intervention developers; a cascaded training or training the trainers model).

A description of the cascaded training model and results pertaining to the second aim are the focus of this paper. A description of the collaborative process used to engage foster parents and key stakeholders (e.g., child welfare system leaders, caseworker supervisors, foster parent associations) in the study, an overview of the intervention, characteristics of the participating foster parents and the children placed with them, and data on the comparability of study participants and decliners are also provided. Results from the first aim (Chamberlain, Price, Reid, Landsverk, Fisher, & Stoolmiller, 2006; Price, Chamberlain, Landsverk, Reid, Leve, & Laurent, 2008) are also briefly reviewed. Finally, implications from this study for conducting effectiveness-level research in child welfare nonspecialty service settings are discussed, as are community efforts to sustain the intervention over time.

Background

Children in foster care are at high risk for behavioral and mental health problems (Landsverk & Garland, 1999; Landsverk, Garland, & Leslie, 2001), which creates challenges for kinship and foster parents. These parents, however, rarely receive meaningful or relevant consultation on strategies for coping with child mental health problems, as evidenced by several recent surveys with foster parents that indicate that obtaining help to understand and manage children’s mental health needs are a priority (Center for the Study of Social Policy, 2002; Pasztor, Hollinger, Inkelas, & Halfon, 2006; Stephenson, 2002a, 2002b). Externalizing problems are an especially salient issue for youth in foster care (Landsverk et al., 2001). Externalizing problems have been shown to predict an increased probability of placement disruption (Chamberlain et al., 2006), and those disruptions, in turn, escalate externalizing problems (Newton, Litrownik, & Landsverk, 2000). Increases in placement changes and placement instability have been found to contribute to an increased risk for delinquency (Ryan & Testa, 2005) and an increased use of mental health services (James, Landsverk, Slymen, & Leslie, 2004).

Over the past three decades, efficacy studies evaluating PMT in non–child welfare settings have documented improved outcomes for youngsters with externalizing problems (e.g., DeGarmo & Forgatch, 2005; Patterson, 2005). While these studies have included children and adolescents who varied in age and severity of problems, all emphasized the need for parents to use a set of core processes, including providing daily encouragement and mentoring, consistent and rational limits, and nonviolent discipline. Outcome data showed that by using these tactics, rates of child problem behaviors typically drop to normal levels in 75% of the cases (Snyder, Reid, & Patterson, 2003). Despite the growing evidence base supporting PMT, approximately only 10% of public child service systems implement evidence-based practices such as PMT (Elliott, 1998; Hoagwood & Olin, 2002; Rones & Hoagwood, 2000). Recent studies in the emerging field of implementation science strongly suggest that the successful incorporation of such interventions into existing practice typically requires pervasive changes at multiple levels, including changes in policy, administrative procedures, and delivery of frontline practice. Furthermore, to implement new interventions and to sustain them in the context of routine practice, factors such as a sense of ownership, collaboration, user-friendly communication and assessments, and compatibility with users’ needs and goals have proven important (Backer, 2000; Gager & Elias, 1997; Rogers, 1995).

In this study, we attempted to address these factors. We used an intervention that was a version of Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (MTFC), a PMT-based approach that has been tested in previous studies with adolescents and children in foster care who have severe externalizing and mental health problems (Chamberlain & Reid, 1991, 1998; Leve & Chamberlain, 2005). We engaged community stakeholders using both top-down and bottom-up approaches in a community participatory process to define the need, identify the target population, and refine and adjust the intervention to be relevant to ethnic and cultural conditions. Our aim was to map the intervention and related procedures onto the on-the-ground ecology of the child welfare systems and to the foster/kinship parent and child population. Therefore, we established very few exclusionary criteria and included all foster and kinship parents (who comprise approximately 40% of the foster caregivers in the United States) who received a new placement of an age-eligible child. The foster or kinship families had no selection criteria; all were included.

Groundwork and Participatory Processes in the Development of the Intervention

Researchers from the Oregon Social Learning Center (OSLC) and from the Child and Adolescent Services Research Center (CASRC) collaborated on the conceptualization and design of the study. OSLC has a history of intervention development (including the PMT and MTFC models), and CASRC has conducted numerous services research studies in child mental health, juvenile justice, and child welfare systems. Additionally, CASRC has a decade-long collaborative relationship with key individuals at the San Diego Health and Human Services (HHS) Agency. The relationship has involved the exchange of information and ideas, joint participation in data analysis projects, and cosponsorship of seminars on child welfare policy; this study was a continuation of this successful community research partnership.

The HHS director of child welfare and the deputy director of policy and planning provided input regarding the study’s goals and content. In addition, HHS management staff, caseworker supervisors, foster parent associations, and foster parents were consulted throughout the development of the intervention. Together, we named the intervention KEEP (keeping foster and kin parents supported and trained). Managers of the six child welfare regions in San Diego County, foster parent licensing specialists, and caseworker supervisors met with study investigators to discuss the intervention. Investigators described outcomes from previous studies, explained the need for using random assignment, and discussed ethical issues related to random assignment. The group made several recommendations regarding implementation of the intervention. Investigators also met with representatives of the local foster parent associations to provide an overview of the study and garner support. Investigators presented the goals and proposed content and design of the intervention as well as recruitment strategies. Comments and suggestions from the representatives were incorporated into the final study procedures.

Addressing Cultural Diversity

A major goal of the study was to develop an intervention that was relevant for the culturally diverse population living in San Diego County. With help from local foster parent associations, a series of focus groups with Latino and African American foster and kin parents were organized to elicit feedback to improve the cultural relevance of the intervention. The focus groups, which included 8 to 10 foster parent participants, provided feedback regarding the goals of the project, the recruitment and assessment procedures, and the curriculum content. Focus group participants expressed strong support for the general notion of using a parent-mediated intervention to attempt to improve child behavior. The participants made several suggestions related to language use and issue framing, particularly around discipline and reinforcement methods. Because almost one-third of the foster/kin parents in San Diego County are Latino, we elected to offer the option of Spanish-speaking intervention groups. Bilingual group facilitators and cofacilitators were hired, and experienced translators translated all materials, assessments, and videotaped presentations into Spanish. Throughout the intervention, group facilitators and cofacilitators provided continuous feedback on the linguistic and cultural appropriateness of the procedures and materials.

Recruitment, Enrollment, and Involvement of Foster Parents

CASRC and HHS developed a recruitment tracking program to provide data on the status and whereabouts of potential subjects and conducted weekly reviews to identify eligible children and foster families. The eligibility requirements were that (a) the child had been in either a kin or a nonkin foster care placement for a minimum of 30 days, (b) the child was between ages 5 and 12, and (c) the child was not considered medically fragile. Once identified, the foster or kin parents of eligible children were contacted by phone and presented with a brief overview of the project. A home visit was scheduled and the foster/kin parents were given a more detailed description of the project. At the home visit, foster/kin parents were also asked to sign an IRB-approved consent form and received a copy of the consent form, a Participant’s Bill of Rights, and contact information for the San Diego State University Institutional Review Board (SDSU IRB). The study was conducted in compliance with OSLC and SDSU IRB and was verified by the results of a random site check by the SDSU IRB administration.

Once enrolled, several strategies were used to maintain parent involvement. Personable and socially competent group facilitators and cofacilitators were hired. Extensive efforts were made to hold group meetings at times and locations convenient to the foster and kin parents, which created complex scheduling challenges. Local community centers, community organization facilities (e.g., boys and girls clubs), and church facilities were used to accommodate the more than 55 parenting groups that met throughout San Diego County. To assist with travel costs, parents were reimbursed $15 per session. Child care with qualified and licensed caregivers was provided, which allowed parents to bring younger children. Refreshments were also provided during each session. Facilitators were trained and supervised to maintain a positive, supportive, and interactive environment during the group sessions while simultaneously adhering to the planned curriculum.

Parents were strongly encouraged to attend parenting sessions; however, home visits were provided for parents who missed a session. Of the sessions, 20.3% (946) were conducted for individual foster or kin parents in their homes, and 79.7% were conducted in the group setting. Facilitators phoned parents weekly to help individualize the curriculum, provide additional support, address questions parents may have felt uncomfortable asking in a group setting, and collect information on the child’s behavior. Foster parents received credit toward their yearly licensing requirement for attending the 16 parenting sessions. Analysis of attendance rates was encouraging: 81% of the foster parents completed 75% or more of the group sessions (12+), and 75% of the foster parents completed 88% or more of the group sessions (14+).

Of the eligible foster parents contacted, 62% agreed to participate and 38% declined. Reasons given for declining to participate included too busy, too much work, or too many children (50%); not interested (43%); family health problems (2%); and concerns about participating in research (5%). Because decliners did not consent to participate, we had limited access to data to compare the participants and decliners. For example, we had no data on foster/kin parent demographic characteristics, or on other contextual factors that might have influenced study outcomes. However, using de-identified data provided by HHS, we were able to compare the numbers of previous placements for children in the participating and declining foster homes. The number of previous placements is considered to be a valid indicator of the level of child risk. For example, Newton et al. (2000) found that the number of previous placements was a strong predictor of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems in foster children. In addition, James et al. (2004) found that increases in the number of placement changes predicted greater rates of outpatient mental health visits. ANOVA and t-tests were used to compare the mean number of placements for participants and decliners in the present trial. No significant differences were found between the numbers of previous placements for children in homes of foster/kin parents who participated versus those who declined.

Participant Characteristics

Foster and Kin Parents

We enrolled 700 relative/kin (n = 237; 34%) and nonrelative/foster (n = 463; 66%) caregivers. The mean age of all caregivers at baseline was 48.6 years (range, 19–81 years). Ethnic backgrounds included Latino (37%), Caucasian (27%), African American (26%), multiethnic (6%), Asian/Pacific Islander (3%), and Native American (1%). Of the caregivers, 60% spoke only English, 32% spoke both English and Spanish, and 8% spoke only Spanish.. Additional background characteristics of the foster and kin parents are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Information for Participating Foster Parents

| Demographic Information | Control | Treatment | Both |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (N = 698) | |||

| Age at Baseline | 47.3 (n = 41) | 49.9 (n = 357) | 48.6 (n = 698) |

| Age Range | 19–81 | 19–79 | 19–81 |

| Gender (N = 700) | |||

| Female | 93% (n = 318) | 94% (n = 339) | 94% (n = 657) |

| Male | 7% (n = 23) | 6% (n = 20) | 6% (n = 43) |

| Race (N = 700) | |||

| Caucasian | 34% (n = 116) | 21% (n = 76) | 27% (n = 192) |

| African American | 24% (n = 81) | 28% (n = 99) | 26% (n = 180) |

| Hispanic/Latino/a | 33% (n = 114) | 41% (n = 148) | 37% (n = 262) |

| Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Other Pacific Islander | 2% (n = 7) | 4% (n = 13) | 3% (n = 20) |

| Native American | 2% (n = 5) | 1% (n = 3) | 1% (n = 8) |

| Multiethnic | 5% (n = 18) | 6% (n = 20) | 6% (n = 38) |

| Languages Spoken (N = 674) | |||

| Only English | 65% (n = 214) | 55% (n = 190) | 60% (n = 404) |

| Only Spanish | 6% (n = 20) | 9% (n = 32) | 8% (n = 52) |

| Both English and Spanish | 29% (n = 96) | 36% (n = 122) | 32% (n = 218) |

| Employment (N = 700) | |||

| Currently Employed (not including foster parenting) | 55% (n = 187) | 44% (n = 156) | 49% (n = 343) |

| Hours Worked per Week (including unemployed foster parents) | 20.0(21.1) (n = 337) | 14.3(20.2) (n = 359) | 17.1(20.8) (n = 696) |

| Education Level (N = 700) | |||

| High School/GED or less | 38% (n = 130) | 43% (n = 155) | 41% (n = 285) |

| Some College | 49% (n = 166) | 44% (n = 159) | 46% (n = 325) |

| Vocational or Technical Degree | 1% (n = 4) | 2% (n = 6) | 1% (n = 10) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 7% (n = 24) | 7% (n = 24) | 7% (n = 48) |

| Graduate Degree | 5% (n = 17) | 4% (n = 15) | 5% (n = 32) |

| Average Number of Children in Home (N = 700) | |||

| Biological Children | .7 (1.0) | .7 (1.1) | .7 (1.1) |

| Step Children | .0 (.1) | .0 (.1) | .0 (.1) |

| Adopted Children | .2 (.6) | .2 (.6) | .2 (.6) |

| Foster Children | 2.2 (1.3) | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.4) |

| Other Children | .3 (1.1) | .1 (.5) | .2 (.9) |

| All Children | 3.5 (2.0) | 3.5 (1.8) | 3.5 (1.9) |

| Foster Children (not including target child) | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.4) |

Children

The mean age of the children at baseline was 8.8 years (range, 4–13 years). Females made up 52% of the sample. Ethnic backgrounds included Latino (33%), Caucasian (22%), multiethnic (22%), African American (21%), Asian/Pacific Islander (1%), and Native American (1%). Of the children, 70% spoke only English, 29% spoke both English and Spanish, and 2% spoke only Spanish. The background characteristics of the foster children are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic Information for Participating Target Children

| Demographic Information | Control | Treatment | Both |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (N = 700) | |||

| Age at Baseline | 8.7(n = 341) | 8.9(n= 359) | 8.8(n = 700) |

| Age Range | 4–13 | 4–13 | 4–13 |

| Relationship to Foster Parent (N = 700) | |||

| Nonkinship | 64% (n = 218) | 68% (n = 245) | 66% (n = 463) |

| Kinship | 36% (n = 123) | 32% (n = 114) | 34% (n = 237) |

| Gender (N = 700) | |||

| Female | 54% (n = 185) | 50% (n = 179) | 52% (n = 364) |

| Male | 46% (n = 156) | 50% (n = 180) | 48% (n = 336) |

| Race (N = 700) | |||

| Caucasian | 25% (n = 84) | 20% (n = 73) | 22% (n = 157) |

| African American | 19% (n = 65) | 23% (n = 83) | 21% (n = 148) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 30% (n = 101) | 35% (n = 127) | 33% (n = 228) |

| Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Other Pacific Islander | 1% (n = 3) | 1% (n = 3) | 1% (n = 6) |

| Native American | 2% (n = 5) | 1% (n = 3) | 1% (n = 8) |

| Caucasian and Hispanic/Latino | 7% (n = 24) | 7% (n = 25) | 7% (n = 49) |

| Caucasian and African American | 3% (n = 11) | 5% (n = 16) | 4% (n = 27) |

| African American and Hispanic/Latino | 4% (n = 14) | 2% (n = 8) | 3% (n = 22) |

| Other Multiracial | 10% (n = 34) | 6% (n = 21) | 8% (n = 55) |

| Languages Spoken (N = 671) | |||

| Only English | 74% (n = 243) | 65% (n = 224) | 70% (n = 467) |

| Only Spanish | 2% (n = 6) | 2% (n = 7) | 2% (n = 13) |

| Both English and Spanish | 24% (n = 79) | 33% (n = 112) | 29% (n = 191) |

Overview of the Intervention and Facilitator Training

Participants who were randomly assigned to the intervention group received 16 weeks of foster/kinship family support and training as well as supervision in behavior management methods. Intervention groups consisted of 3 to 10 foster parents and were conducted by a trained facilitator and cofacilitator team. The 90-minute sessions were structured so that the curriculum content was integrated into group discussions. The overall objective was to give parents effective tools for dealing with child externalizing and other behavioral and emotional problems and to provide support for implementing those tools. Curriculum topics included framing the foster/kin parents’ central role in altering the life course trajectories of children, methods for encouraging child cooperation and reinforcing normative behavior, using behavioral contingencies including effective limit setting, and balancing encouragement and limits with an emphasis on increasing rates of positive reinforcement to the child. In addition, parenting sessions included strategies for managing difficult problem behaviors (including covert behaviors), promoting school success, encouraging positive peer relationships, and tactics for managing stress incurred by providing foster care. The facilitators emphasized active learning methods; illustrations of primary concepts were presented via role-playing and videotapes. At the end of each meeting, facilitators introduced a home practice assignment related to the topics covered during the session. These assignments were aimed at having parents implement the behavioral procedures reviewed at the group meetings. If foster/kin parents missed a parent training session, material from the missed session was delivered during a home visit at a time convenient for the parents (20.3% of the total sessions). This method of transmitting information has been found to effectively increase the intervention dosage for families who miss intervention sessions (Reid & Eddy, 1997).

Facilitators were paraprofessionals who had no prior experience with behavior management or with other parent-mediated interventions. Rather, experience with group settings, interpersonal skills, motivation, and knowledge of children were given high priority in selecting the facilitators and cofacilitators. They were trained on the curriculum during a five-day session where role-playing was emphasized. Prior to groups with actual foster parents, the facilitators conducted and received feedback on practice groups that they videotaped.

Overview of Outcomes on Changes in Child Behavior and Parenting Practices

Child behavioral outcomes were measured using the parent daily report (PDR) checklist (Chamberlain et al., 2006; Kazdin & Wassell, 2000). To minimize the bias associated with retrospective recall of child behavior, the PDR was designed to ask parents to endorse the occurrence/nonoccurrence of specific behaviors within the previous 24 hours. PDRs were collected in a brief telephone interview; this method has been shown to correlate with in-home behavioral observations (Patterson, 1976) and with long-term outcomes such as arrests (Chamberlain, 2003) and placement disruptions (Chamberlain et al., 2006). In this study, PDR data were collected from foster and kin parents for three days at baseline and three days at treatment termination. No differences existed between the behavior rates reported by intervention parents and those reported by control parents at baseline. At treatment termination, however, foster/kin parents in the KEEP intervention condition reported significantly fewer child behavior problems than those in the control condition (M = 4.37 [3.91] and 5.44 [4.15], respectively, p < .05). In addition, these changes in child behavior were found to be mediated by changes in parenting behavior. At the five-month interview postbaseline, foster parents who participated in the KEEP groups showed an increase in the proportion of positive reinforcements relative to discipline parenting practices, and this increase predicted a decrease in child problem behaviors (Chamberlain, Price, Leve, Laurent, Landsverk, & Reid, 2008). Children of parents in the KEEP group were also found to have higher rates of reunification with biological or adoptive families and fewer placement disruptions than those in the control condition (Price et al., 2008).

Results on the Cascaded Model of Training Interventionists

The second goal of our research was to compare the effects of the intervention on child behavioral outcomes with and without the involvement of the original developers (see Figure 1). Phase 1 of the cascade occurred in a study conducted in three Oregon counties (Chamberlain, Moreland, & Reid, 1992). In that study, foster families were randomly assigned to one of three groups: (a) enhanced services plus a monthly stipend, (b) a monthly stipend only, or (c) a foster-care-as-usual control group. Treatment for the enhanced groups was conducted by an experienced foster parent who was well versed in the OSLC PMT model and supervised by the treatment developer. In the current study, phase 2 of the cascade was implemented. In this phase, the treatment for foster parents was delivered by paraprofessional staff hired by CASRC. The CASRC staff was supervised weekly by both an on-site supervisor and an experienced OSLC clinical consultant. The consultation from the OSLC clinical consultant took place during weekly telephone calls. Prior to the calls, the OSLC consultant viewed videotapes of the previous foster parent group meetings. The calls were one to one-and-a-half hours long and included discussions of clinical strategies. During phase 3 of the cascade (also in the current study), the San Diego intervention staff trained and supervised a second cohort of interventionists. The OSLC clinical consultant had no direct contact with the staff in the second cohort, although they did supervise cohort 1’s supervision of the cohort 2 interventionists. In all phases of the study, the foster parent group sessions were videotaped, and the tapes were reviewed during supervision sessions.

Figure 1.

The Cascaded Training Model

Baseline rates of behavior problems did not differ for phase 2 and phase 3 children (M = 5.86 and 5.82, respectively). The results of the cascaded training model also showed that there were no differences between rates of child problems at treatment termination for those who participated in phases 2 and 3 (M = 4.84 and 4.95, respectively). Assignment to the KEEP intervention group was associated with a significant decrease in child problems from baseline to termination; however, there was no decrement in the treatment effect when the developers of the intervention pulled back and had the staff trained in phase 2 provide training and supervision for phase 3 interventionists. These data support the notion that given proper training and ongoing supervision, the intervention could be transported to third generation interventionists who were not directly trained or supervised by the original developers of the intervention.

Supervision and Communication

Communication between the research teams in Oregon and San Diego was maintained through monthly meetings in San Diego. Every six months, the investigators and project coordinators met at OSLC or CASRC to evaluate and correct problems in the recruitment, intervention, and assessment procedures. San Diego HHS managers were invited to the meetings and participated in several. HHS received quarterly updates about the study’s progress and had regular contact with CASRC staff regarding recruitment and clinical issues. In addition, the Oregon and San Diego clinical teams communicated weekly regarding clinical issues; facilitators and cofacilitators in both cohorts received weekly clinical supervision. All sessions were videotaped and reviewed by the on-site supervisor, who identified the key processes and events to be discussed during weekly consultation calls with the OSLC clinical consultant. During those calls, issues related to curriculum adherence and attention to group dynamics, processes, and the individual needs of families as well as clinical development of the facilitator and cofacilitator were discussed. This supervision process enabled group facilitators to obtain specific feedback on their own performance and provided a mechanism for monitoring the progress of each parenting group.

Sustainability and Challenges of Full Integration into Routine Practice

Prior to completion of the study, HHS officials expressed interest in continuing the intervention and in working toward integrating it into their regular practice. HHS submitted an application to California and received funding to support 10 to 12 parent groups for the following year.

Because mental health services for foster children are typically provided through private contractors in San Diego County, a contractor was selected to provide the parent group facilitation. Facilitators were trained in the intervention model, sessions were videotaped, and the tapes were reviewed weekly to monitor adherence to the intervention goals, curriculum, and study procedures. Pre- and post-assessments of family and child functioning and select system outcomes (e.g., the number and nature of placement changes) are being collected so that they can be benchmarked against the outcomes achieved in the study.

Several challenges remain for fully integrating the KEEP intervention into routine practice. These challenges include developing systems and protocols for obtaining referrals and establishing effective communication channels with caseworkers, sustaining funding for adherence monitoring, determining which outcomes can be feasibly tracked and monitoring those outcomes, maintaining a trained and supported interventionist core, and providing the interventionists with high-quality supervision.

Implications for Integrating Evidence-Based Practices into Usual Care Child Service Systems

Against the backdrop of research showing that powerful parenting interventions, though developed and validated through rigorous research, are rarely implemented in child welfare agencies, the results of this study are encouraging. The current study demonstrates that it is possible to develop strong and effective partnerships involving diverse stakeholders, including foster parents and their membership organizations, administrators of child services agencies, services researchers, and intervention developers and researchers. This study also indicates that these collaborations have the potential to produce significant improvements in services for extremely vulnerable children. Further, such collaborations have the potential to improve the children’s daily behavior, their adjustment to foster and kin placements, and their long-term outcomes. The encouraging results reported in this study, however, represent only a promissory note for implementation of the intervention.

Interventions that have proven useful in carefully controlled efficacy trials have little chance of reaching vulnerable children without buy in from and collaboration with relevant community service agencies and providers. In this regard, this intervention trial affirmed the necessity of developing strong partnerships between program developers, service agencies, and service providers. In this study, such partnerships were formed early, at the initial planning stages of implementation. From the beginning, HHS administrators were active participants in adapting the intervention to their local ecology, to the characteristics of their service population, and to the structure of their agency. It is likely that this level of initial involvement laid the groundwork for the intervention to be implemented after the study was over. The collaboration leading to this effectiveness trial, however, developed over the course of several years. Without the long-term working relationships between the service agency (San Diego HHS) and CASRC and between CASRC and OSLC, this intervention trial could not have been completed.

Service agencies vary tremendously in the obstacles they face in adopting new evidence-based practices. Agencies differ in organization, financial structure, training procedures, and community contextual issues. Each implementation represents a creative task in which the specific components of the intervention and assessment strategy must be carefully adjusted to meet the unique requirements of the agency, community, service providers, and child population. These creative implementations must also maintain the integrity of the intervention that was evaluated in previous efficacy trials. To successfully implement the interventions, rigorous and feasible assessments are critical in each new site. We are just beginning to learn how to develop rigorous assessment strategies, such as the PDR, that can be used in existing agencies.

To readily translate new evidence-based interventions into wide practice, it is necessary to conduct rigorous, systematic, collaborative research to understand the potential contributions of each of the many stakeholders to these implementations and to develop procedures to improve and facilitate the stakeholders’ involvement in all phases of implementation. Further, it is imperative to develop new research designs that are not disruptive to agency business as usual and that provide useful information to the field of implementation. The current randomized trial represents a small step in this direction.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by NIMH grant MH60195 and NIDA grants DA020172-01A1 and DA017592. The authors wish to thank the San Diego County Department of Health and Human Services, Courtenay Padgett (OSLC), and Jan Price (CASRC) for their assistance with recruitment, data collection, and management, and Janet Davis, Norma Talamantes, and Melissa Woods (lead interventionists).

References

- Backer TE. The failure of success: Challenges of disseminating effective substance abuse prevention programs. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:363–373. [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Study of Social Policy. Arkansas foster parent survey analysis for the division of child and family services of the Arkansas department of human services. Little Rock, AR: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P. Treating chronic juvenile offenders: Advances made through the Oregon multidimensional treatment foster care model. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Moreland S, Reid K. Enhanced services and stipends for foster parents: Effects on retention rates and outcomes for children. Child Welfare. 1992;71:387–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price J, Leve LD, Laurent H, Landsverk J, Reid JB. Prevention of behavior problems for children in foster care: Outcomes and mediation effects. Prevention Science. 2008;9:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price JM, Reid JB, Landsverk J, Fisher PA, Stoolmiller M. Who disrupts from placement in foster and kinship care? Child Abuse and Neglect. 2006;30:409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Reid JB. Using a specialized foster care community treatment model for children and adolescents leaving the state mental hospital. Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19:266–276. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Reid JB. Comparison of two community alternatives to incarceration for chronic juvenile offenders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;6:624–633. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Forgatch MS. Early development of delinquency within divorced families: Evaluating a randomized preventive intervention trial. Developmental Science. 2005;8:229–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Farmer EMZ, Barth RP, Greene KM, Reid J, Landsverk J. Current status and evidence base of training for foster and treatment foster parents. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:1403–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, editor. Blueprints for violence prevention. Boulder: Institute of Behavioral Science, Regents of the University of Colorado; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gager PJ, Elias MJ. Implementing prevention programs in high-risk environments: Application of the resiliency paradigm. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1997;67:363–373. doi: 10.1037/h0080239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K, Olin S. The NIMH blueprint for change report: Research priorities in child and adolescent mental health. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:760–767. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James S, Landsverk J, Slymen DJ, Leslie LK. Predictors of outpatient mental health service use: The role of foster care placement change. Mental Health Services Research. 2004;6:127–141. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000036487.39001.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Wassell G. Therapeutic changes in children, parents, and families resulting from treatment of children with conduct problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:414–420. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsverk J, Garland AF. Foster care and pathways to mental health services. In: Curtis PA, Grady DE, editors. The foster care crisis: Translating research into practice and policy. Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press; 1999. pp. 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Landsverk JA, Garland AF, Leslie LK. Mental health services for children reported to protective services. In: Myers JEB, Hendrix CT, Berliner L, Jenny C, Briere JN, Reid T, editors. APSAC handbook on child maltreatment. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. pp. 487–507. [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Chamberlain P. Association with delinquent peers: Intervention effects for youth in the juvenile justice system. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3571-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton RR, Litrownik AJ, Landsverk JA. Children and youth in foster care: Disentangling the relationship between problem behaviors and number of placements. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2000;24:1363–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. The aggressive child: Victim and architect of a coercive system. In: Hamerlynck LA, Handy LC, Mash EJ, editors. Behavior modification and families: I. Theory and research. II. Applications and developments. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1976. pp. 267–316. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. The next generation of PMTO models. The Behavior Therapist. 2005;28(2):25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Price JM, Chamberlain P, Landsverk J, Reid JB, Leve LD, Laurent H. Effects of a foster parent training intervention on placement changes of children in foster care. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:64–75. doi: 10.1177/1077559507310612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasztor EM, Hollinger DS, Inkelas M, Halfon N. Health and mental health services for children in foster care: The central role of foster parents. Child Welfare. 2006;85 (1):33–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid JB, Eddy JM. The prevention of antisocial behavior: Some considerations in the search for effective interventions. In: Stoff DM, Breiling J, Maser JD, editors. Handbook of antisocial behavior. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. pp. 343–356. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 4. New York: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rones M, Hoagwood K. School-based mental health services: A research review. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review. 2000;3(4):223–241. doi: 10.1023/a:1026425104386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JP, Testa MF. Child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: Investigating the role of placement and placement instability. Children and Youth Services Review. 2005;27:227–249. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JJ, Reid JB, Patterson GR. A social learning model of child and adolescent antisocial behavior. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, editors. Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson L. Parent association of Washington state training needs survey: A report on the survey of foster parents in region 1. Olympia, WA: Foster Parents Association of Washington State; 2002a. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson L. Parent association of Washington state training needs survey: A report on the survey of foster parents in region 2. Olympia, WA: Foster Parents Association of Washington State; 2002b. [Google Scholar]