Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the independent risk factors for ovarian metastasis in cervical cancer.

Methods

Among 1,040 consecutive patients who underwent operation for cervical cancer at our institution from January 1998 to July 2007, a total of 625 patients had both ovaries removed during primary operation were retrospectively selected by medical records. In order to determine clinicopathological risk factors for ovarian metastasis, we analyzed patients' demographics, FIGO stage, and other pathologic findings. The Chi-square or Fisher's extract tests were used to compare any association of clinicopathologic variables with ovarian metastasis. For multivariate analysis, the log regression models were used to determine independent predictors for ovarian metastasis.

Results

Overall, ovarian metastasis was detected in fourteen (2.2%) patients: two of 473 patients with squamous cell carcinoma (0.4%) and twelve of 151 patients with non-squamous cell carcinoma (7.9%), respectively (p<0.0001). Univariate analysis represents age (≤45 vs. >45 years: p=0.347), histologic types (squamous vs. non-squamous, p<0.0001), FIGO stages (IA1-IIA ≤4 cm vs. IB2-IIB >4 cm, p=0.054), stromal invasion (≤1/2 vs. >1/2, p=0.788), lymph node metastasis (positive vs. negative, p=0.007), parametrium (involved vs. uninvolved, p=0.145), upper vagina (involved vs. uninvolved, p=0.003), uterine corpus (involved vs. uninvolved, p<0.0001), and margin status (involved vs. uninvolved, p=0.017). By multivariate analysis, uterine corpus involvement was the only independent risk factor for ovarian metastasis (p=0.008), in addition to histologic types (p<0.0001).

Conclusion

Based on our study, uterine involvement of cervical cancer is an independent predictor for ovarian metastasis, except histologic types. Ovarian preservation in cervical cancer may be safely performed only when no involvement of uterine corpus is present.

Keywords: Ovarian metastasis, Cervical cancer, Squamous cell carcinoma, Adenocarcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Due to cervicovaginal screening for cervical cancer and it precursors, the incidence of cervical cancer, especially squamous cell carcinoma, has been greatly reduced during the past 50 years.1,2 However, the relative and absolute incidence of adenocarcinoma of the cervix has increased during the past 3 decades, especially among young women in their 20s and 30s.1,3

Ovarian metastasis rarely occurs in cervical cancer and has not been included in the clinical staging system. The issue of ovarian preservation becomes relevant for young patients and their quality of care. Since McCall et al.4 reported that the risk of ovarian involvement is low in early squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix, ovarian preservation at the time of radical hysterectomy is well established in young patients undergoing surgery for early stage of cervical cancer. In addition, the Gynecologic Oncology Group showed only 2 patients among 121 patients with stage IB adenocarcinoma that showed ovarian metastasis and also extra-ovarian disease.5 Recently, a Cooperative Task Force Study in Japan demonstrated that age, FIGO stages, histology, and unaffected peripheral stromal thickness were independent risk factors for ovarian metastasis.6 Except for histologic type, other pathologic risk factors or predictors for ovarian metastasis have not been established in uterine cervical cancer at present.

Therefore, we retrospectively investigated 625 consecutive patients with cervical cancer including 14 cases with ovarian metastasis confirmed after operation to identify the independent risk factors associated with ovarian metastasis.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

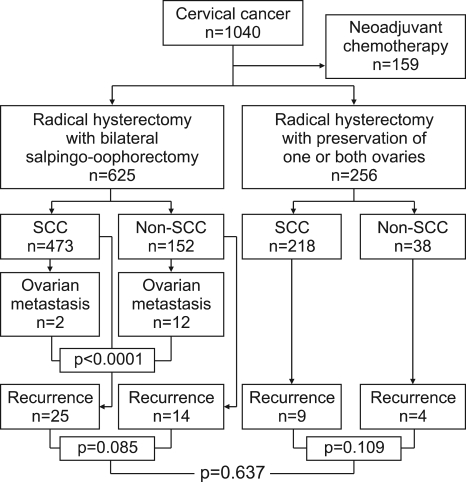

Among the 1,040 consecutive patients diagnosed with cervical cancer at our institute from January 1998 to July 2007, a total of 881 patients who underwent primary operation for cervical cancer were retrospectively searched and included in our study, excluding 159 subjects who received chemotherapy before operation. As shown in Fig. 1, a total of 625 (70.9%) patients received radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection, including bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with or without appendectomy. The remaining 256 (29.1%) patients received the same operation, but with preservation of one or both ovaries. In order to determine clinicopathological risk factors for ovarian metastasis in cervical cancer, we reviewed the medical records including patients' clinical data, demographic data and histopathologic records, which consists of FIGO stages, grades, histologic types (squamous vs. non-squamous), depth of stromal invasion, lymph node metastasis, uterine corpus involvement, parametrial invasion, vaginal involvement, resection margin status and follow-up status. Follow-up data, including date and site of recurrence, were collected for all patients till terminally hopeless or expired state.

Fig. 1.

Overview of study population. SCC: squamous cell carcinoma.

Histopathologic slides were separately reviewed by two different expert pathologists of our institution with a great deal of experience in gynecological malignancies to confirm the diagnosis.

All patients were followed up every 3 months for the first two years, every 4 months for the third year, and every 6 months up to 5 years, and once or twice a year thereafter. Time to recurrence was defined as the time between the first day of treatment and either the day of evidence of recurrent disease or the starting day of second-line treatment.

The Chi-square or the Fisher's extract tests were used to compare any association of prognostic factors with ovarian metastasis. For multivariate analysis, the log regression models were used to detect independent prognostic factors for ovarian metastasis. All analyses were performed using SPSS 12 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) and p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

This study focused on the independent predictors for ovarian metastasis in cervical cancer at the time of operation. Eligible patients are a total of 625 consecutive subjects (median age of 52.2, range 22.2-82.2) who underwent primary operation for uterine cervical cancer as shown in Fig. 1. Ovarian metastasis was overall detected in 2.2% (14/625), which were 0.4% (2/473) of patients with squamous cell carcinoma and 7.9% (12/151) of those with non-squamous cell carcinoma (p<0.0001). Histopathology of non-squamous cell carcinomashowing ovarian metastasis consisted of adenocarcinoma malignun (n=8), adenosquamous cell carcinoma (n=1), small cell carcinoma (n=1) and neuroendocrine type histology (n=2). Non-squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix also had significantly higher recurrences (p=0.018) and an increasing tendency to involve the uterus corpus than did squamous cell carcinoma, even though statistically insignificant (p=0.094). However, the other baseline characteristics, such as patients' age and other histologic findings were well-balanced between the squamous cell carcinoma group and non-squamous cell carcinoma group (data not shown).

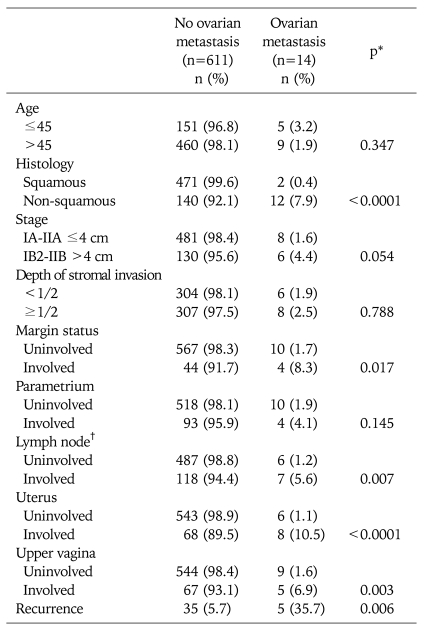

Univariate analysis for ovarian metastasis represents age (≤45 vs. >45 years: p=0.347), histologic types (squamous vs. non-squamous, p< .0001), FIGO stage (IA1-IIA ≤4 cm vs. IB2-IIB >4 cm: p=0.054), depth of stromal invasion (≤1/2 vs. >1/2 p=0.788), lymph node metastasis (positive vs. negative, p=0.007), parametrium (involved vs. uninvolved, p=0.145), upper vagina (involved vs. uninvolved, p=0.003), uterine corpus (involved vs. uninvolved, p<0.0001) and status of resection margin (involved vs. uninvolved, p=0.007) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis for ovarian metastasis in uterine cervical cancer

*p value by linear-by-linear association, †Excluding patients not performed pelvic lymph node dissection

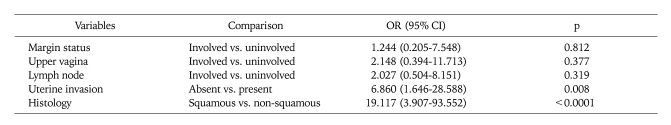

By multivariate analysis, the independent factors for ovarian metastasis were uterine involvement (p=0.008) as well as histologic types of non-squamous cell carcinoma (p<0.0001) including adenoma malignum and neuroendocrine tumor (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis for ovarian metastasis in uterine cervical cancer

DISCUSSION

Ovarian metastasis is a rare event in cervical cancer as shown in the results of our study (2.2%), which is similar to other reports.5-8 Therefore, ovarian preservation may be safely performed, especially in young patients who benefits from ovaries preservation.

There have been several reports to evaluate the independent clinicopathological risk factors for ovarian metastasis in uterine cervical cancer,9-11 however, it has been known to be difficult to diagnose metastatic lesions of ovary. The retrospective study of the Gynecologic Oncologic Group demonstrated that the ovarian metastasis of patients with adenocarcinoma (1.7%) was more frequent, but not significantly different, when compared to those with squamous cell carcinoma (0.5%), and all six patients with ovarian metastasis had represented other evidence of extracervical disease.5

However, Nakanishi et al.12 reported that ovarian metastases were significantly more common in adenocarcinoma compared with squamous cell carcinoma in a series of 14 patients (1.3%) with squamous cell carcinoma and 15 (6.3%) with adenocarcinoma among a total of 1,304 patients with FIGO stage IA-IIB cervical cancer. According to a Cooperative Task Force study, in addition to histology, FIGO stage and age, unaffected peripheral stromal thickness (<3 mm), were independent risk factors for ovarian metastases in 1,965 patients.6

Based on the present data of our study, uterine involvement of cervical carcinoma is an independent risk factor for ovarian metastasis, except for tumor histologic type. Five of fourteen patients with ovarian metastasis showed intraoperative findings of omental or pelvic peritoneal tumor involvement, and were mainly non-squamous cell carcinoma patients. In contrast, none of those with no ovarian metastasis reveal evidence of disease of the omentum or pelvic cavity (data not shown).

One possible explanation is that with uterine involvement, cervical adenocarcinoma appears to be a similar act to endometrial cancer, often characterized as the extracervical or pelvic spread including the ovary and peritoneum. Among the non-squamous cell carcinoma group of our study population, seven out of 23 patients with uterine involvement represented ovarian metastasis, while only five out of 129 subjects with no evidence of uterine involvement showed ovarian metastasis. In contrast, among the squamous cell carcinoma subpopulation, ovarian metastasis was detected in one case of each of the two groups (1/52 and 1/420, p=0.212) according the uterine involvement, respectively. Therefore, non-squamous cell carcinoma including adenocarcinoma is more likely to spread to extrauterine lesions than squamous cell carcinoma with uterine corpus involvement. In other studies, possible routes of spread to the ovary from cervical cancer have varied; via hematologic metastasis,9 or lymphatic drainage and transtubal drainage.10

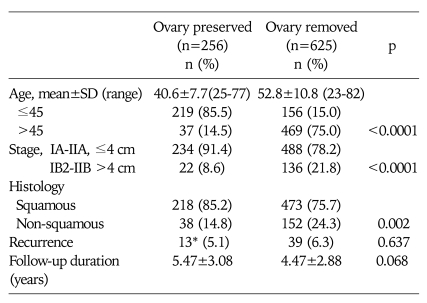

The clinical and pathological comparisons of the study population and the 256 patients with ovarian preservation at the time of radical hysterectomy are summarized in Table 3. Disease recurrence often occurs in the non-squamous cell carcinoma group, which also represents more frequent ovarian metastasis than the squamous cell carcinoma group, as shown in Fig. 1. Mean of time to recurrence was 1.5 years (±1.3 years) in all cases with recurrence. Although significantly younger age and early stage cervical cancer was observed in the group with one or both preserved ovary, ovarian preservation did not show any deterioration with regard to prognosis or recurrence of uterine cervix cancer, as depicted in Table 3 (p=0.637). Moreover, even though recurrent disease was detected in twelve out of 292 patients with one or both preserved ovaries, none demonstrated evidence of disease of the preserved ovary, and which is in agreement with other reports, especially the GOG retrospective study.5,6

Table 3.

Clinicopathological comparison in terms of ovarian operation in the cervical cancer

*Cases showing recurrence in lung (n=3), supraclavicular lymph node (n=4), bone and peritoneal seeding (n=1), psoas muscle, pelvic lymph nodes and vaginal stump (n=7)

Ovarian preservation, therefore, should be pursued since the maintenance of ovarian function is beneficial to young patients without significantly increasing their risk of recurrences.

The limitation of our study is that there was no intraoperative evaluation of uterine involvement in the specimen, or no evaluation of its correlation with pathologic findings in patients with cervical cancer. Therefore, it is required to evaluate the correlation of its permanent pathologic findings with intraoperative gross evaluation of uterine corpus or preoperative endometrial biopsy by curettage. Furthermore, no preoperative findings of radiology images were considered in our study for the preoperative determination of uterine involvement. Consequently, it should also be warranted whether preoperative radiologic images e.g., pelvis magnetic resonance image or computed tomography could predict the uterine involvement of cervical cancer and correlate with intraoperative findings.

Taken together, ovarian preservation could be safely performed in patients with the uterine cervical cancer of non-squamous cell as well as squamous cell, only if no pelvic peritoneal and no uterine corpus involvement.

References

- 1.Chung HH, Jang MJ, Jung KW, Won YJ, Shin HR, Kim JW, et al. Cervical cancer incidence and survival in Korea: 1993-2002. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:1833–1838. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith HO, Tiffany MF, Qualls CR, Key CR. The rising incidence of adenocarcinoma relative to squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix in the United States: A 24-year population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:97–105. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benedetti-Panici P, Maneschi F, D'Andrea G, Cutillo G, Rabitti C, Congiu M, et al. Early cervical carcinoma: The natural history of lymph node involvement redefined on the basis of thorough parametrectomy and giant section study. Cancer. 2000;88:2267–2274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCALL ML, Keaty EC, Thompson JD. Conservation of ovarian tissue in the treatment of carcinoma of the cervix with radical surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1958;75:590–600. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(58)90614-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutton GP, Bundy BN, Delgado G, Sevin BU, Creasman WT, Major FJ, et al. Ovarian metastases in stage IB carcinoma of the cervix: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(1 Pt 1):50–53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91828-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landoni F, Zanagnolo V, Lovato-Diaz L, Maneo A, Rossi R, Gadducci A, et al. Ovarian metastases in early-stage cervical cancer (IA2-IIA): A multicenter retrospective study of 1965 patients (a Cooperative Task Force study) Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:623–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimada M, Kigawa J, Nishimura R, Yamaguchi S, Kuzuya K, Nakanishi T, et al. Ovarian metastasis in carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:234–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singleton HM, Orr JW. Cancer of the cervix. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Company; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu HS, Yen MS, Lai CR, Ng HT. Ovarian metastasis from cervical carcinoma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;57:173–178. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(97)02848-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabata M, Ichinoe K, Sakuragi N, Shiina Y, Yamaguchi T, Mabuchi Y. Incidence of ovarian metastasis in patients with cancer of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1987;28:255–261. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(87)90170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Natsume N, Aoki Y, Kase H, Kashima K, Sugaya S, Tanaka K. Ovarian metastasis in stage IB and II cervical adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;74:255–258. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakanishi T, Wakai K, Ishikawa H, Nawa A, Suzuki Y, Nakamura S, et al. A comparison of ovarian metastasis between squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82:504–509. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]