Abstract

Hippocampal function, including spatial cognition and stress responses, matures during adolescence. In addition, hippocampal neuron structure is modified by gonadal steroid hormones, which increase dramatically at this time. This study investigated pubertal changes in dendritic complexity of dentate gyrus neurons. Dendrites, spines, and cell bodies of Golgiimpregnated neurons from the granule cell layer were traced in pre-, mid-, and late pubertal male Syrian hamsters (21, 35, and 49 days of age). Sholl analysis determined the number of intersections and total dendritic length contained in concentric spheres set at 25 μm increments from the soma. Spine densities were quantified separately in proximal and distal segments of a subset of neurons used for Sholl analysis. We found that the structure of neurons in the lower, but not upper, blade of the dentate gyrus changed during adolescence. The lower, infrapyramidal blade showed pruning of dendrites close to the cell body and increases in distal dendritic spine densities across adolescence. These data demonstrate that dentate gyrus neurons undergo substantial structural remodeling during adolescence and that patterns of maturation are region specific. Furthermore, these changes in dendrite structure, which alter the electrophysiological properties of granule cells, are likely related to the adolescent development of hippocampal-dependent cognitive functions such as learning and memory, as well as hippocampus-mediated stress responsivity.

Keywords: Adolescence, Puberty, Dentate Gyrus, Neuron Structure, Dendrite, Dendritic Spines

INTRODUCTION

During adolescence, structural remodeling occurs in a number of brain regions, including the hippocampus, where neural plasticity is a characteristic throughout the lifespan (Koshibu et al., 2004; Lenroot & Giedd, 2006). New neurons are continuously added to the dentate gyrus, allowing for modulation of hippocampal function and possibly contributing to learning and memory (Leuner et al., 2006). However, the rate of postnatal neurogenesis is not constant. Neurogenesis is highest during the perinatal period (Bayer, 1980) and is higher in adolescence than in adulthood (He & Crews, 2007). Adolescence is also a period of rapid behavioral and physiological change. Increases in circulating steroids accompany reproductive maturation and may influence the development of neuronal structure in the hippocampus and other brain regions (Cooke & Woolley, 2005; Giedd et al., 2006). Likewise, developmental changes in learning and memory occur in conjunction with the adolescent development of a variety of social and nonsocial behaviors (Spear, 2000; Sisk & Zehr, 2005; Shors, 2006). This study examined the dentate gyrus of male hamsters to determine if structural remodeling of individual neurons occurs during this period of neural, physiological, and behavioral development.

Several hippocampal functions mature during adolescence in male rodents. First, although sex differences in strategies for performing spatial tasks are observed in adulthood (McCarthy & Konkle, 2005), many sex differences in spatial performance are not observed before puberty (Galea et al., 1994; Kanit et al., 2000), indicating that development of navigation task performance may occur during adolescence. In addition, the effects of environment on some social behaviors emerge during puberty (Primus & Kellogg, 1989). Specifically, pairs of adult male rats spend less time interacting and engaging in social behavior in an unfamiliar environment than in a familiar environment, but prepubertal male rats interact similarly in the two environments (Primus & Kellogg, 1989). This change indicates a developmental shift during adolescence of either responses to environmental and social stimuli or to the anxiogenic properties of unfamiliar environments (Primus & Kellogg, 1989), both of which are controlled, at least in part, by the dentate gyrus and the hippocampus. Stress responsiveness in males also matures during adolescence, with adult males returning much more quickly than prepubertal males to baseline corticosterone levels after exposure to a stressor (Romeo et al., 2004). Interestingly, maturation of stress responsiveness and hippocampal-dependent learning seems to be intertwined in male rodents (Hodes & Shors, 2005). Specifically, stress has little effect on associative learning before puberty but dramatically facilitates learning during adolescence (Hodes & Shors, 2005). Finally, impairments in hippocampal-dependent, contextual fear conditioning emerge during puberty in TGF-α deficient male mice (Koshibu et al., 2005). Since TGF-α increases progenitor cell proliferation (Junier, 2000; Abrous et al., 2005), these impairments in TGF-α deficient mice suggest that neurons normally born in the dentate gyrus during adolescence are necessary for contextual fear conditioning.

Taken together, these behavioral changes indicate that the hippocampus in general and the dentate gyrus in particular undergo structural and functional remodeling during adolescence. In fact, the hippocampus is one of two brain regions in mice showing the largest changes in structure during adolescence when quantified using three-dimensional MRI imaging (Koshibu et al., 2004). Environmental enrichment and social experience are additional variables which alter both hippocampal-dependent behaviors and neuron structure (Juraska et al., 1985; Bartesaghi & Serrai, 2001; Faherty et al., 2003), suggesting that adolescent maturation of hippocampal-dependent behaviors may be linked to changes in dentate gyrus neuron structure. Interestingly, development of dendritic morphology in neurons from the dentate gyrus and hilus differs in the upper versus lower blade in prepubertal guinea pigs (Bartesaghi et al., 2003; Guidi et al., 2006), suggesting that development of dendritic morphology in dentate gyrus neurons may also differ in the upper and lower blades. The upper and lower blades display different patterns of immediate-early gene activity in response to both spatial tasks (Chawla et al., 2005) and stress paradigms (Fevurly & Spencer, 2004), indicating that the two blades are neither structurally nor functionally homogenous in adults.

Increases in gonadal hormones, a hallmark of pubertal development, also influence hippocampal function and dendritic morphology (reviewed by McCarthy & Konkle, 2005; MacLusky et al., 2006). In male mice, dendritic spine density in CA1 fluctuates with circulating testosterone levels, indicating an activational effect of testosterone on dendritic morphology (Meyer et al., 1978; Leranth et al., 2003). Exposure to testosterone during puberty induces a permanent shift from long-term potentiation to long-term depression in response to tetanus (Hebbard et al., 2003), indicating that gonadal hormones also act via organizational mechanisms during adolescence.

Based on the neural, hormonal, and behavioral changes that occur during adolescence, we hypothesized that adolescent brain development includes increases in dentate gyrus dendritic elaboration and spine densities. We quantified dendritic elaboration, spine densities, and soma size of dentate gyrus neurons from pre- mid-, and late adolescent male hamsters. Due to the anatomical and functional differences observed in the upper and lower blades of the dentate gyrus (Scharfman et al., 2002), we analyzed the two blades separately. We predicted that the upper blade would show greater morphological change than the lower blade for two reasons. First, the upper blade is closely tied to a variety of spatial behaviors and stress responses that mature during adolescence. Second, the upper blade has a greater concentration of androgen receptors than the lower blade (Kerr et al., 1995).

METHODS

Subjects

In hamsters, puberty begins around 28 days of age (Miller et al., 1977; Sisk & Turek, 1983). Testosterone levels are below assay sensitivity (< 0.2 ng/ml) at 21 days of age, increase to just under 2 ng/ml by 35 days of age, and are at adult typical levels of over 3 ng/ml by 49 days of age (Zehr et al., 2006). Based on these physiological measures, age groups in this study were defined as pre-adolescent (P20−22), mid-adolescent (P34−36), or late-adolescent (P47-P49).

This study used tissue from a previous study that examined adolescent development of sexual behavior and neuron structure in the medial amygdala, and detailed experimental procedures are reported elsewhere (Zehr et al., 2006). Briefly, male Syrian hamsters were received from Harlan Sprague-Dawley at 18 days of age (P18). Males were weaned at P19 into same-aged groups of 6 animals with free access to water and food (Teklad Rodent Diet No 8640, Harlan). Subjects lived in social groups without manipulation until pre-adolescence (P20−22), middle adolescence (P34−36), or late adolescence (P48−50). Tissue was collected from 2 males in each age group on three successive days. Subjects lived in rooms maintained at 22±2°C with a light-dark cycle of 14 hr light/day (lights off at 1600h EST). Experiments followed the guidelines of the NIH Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Subjects and were approved by the Michigan State University institutional animal care and use committee.

Initially, each age group contained 6 animals. However, four subjects (n=2, P21; n=1, P35; n=1, P49) showed an irregular pattern of hippocampal Golgi impregnation and were excluded from structural analysis of neurons. In the remaining 14 subjects (n=4, P21; n=5, P35; n=5, P49), dendritic branching, spine densities, and soma size were quantified.

Golgi Histology

The Golgi-impregnation methods used in the present study were adapted from Gomez and Newman (1991). Males were anesthetized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (130 mg/kg ip, Nembutal, Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL). Golgi impregnation began with intracardial perfusion of 100 ml 0.1M phosphate buffered saline with 0.1% sodium nitrite followed by 250 ml of 2.4% potassium dichromate, 6% chloral hydrate, 1.5% potassium chlorate, and 4% formaldehyde in distilled water. Brains were kept in the perfusate for 24 hours, followed by 3% potassium dichromate for 3 days, and 1% silver nitrate for 8 days. Sections were cut on a freezing microtome set at 120 μm, quickly dehydrated in ethanols and xylene, mounted serially, and coverslipped using DPX mounting medium (Biochemika, Sigma Cat. No. 44581).

Quantification of Neuron Structure

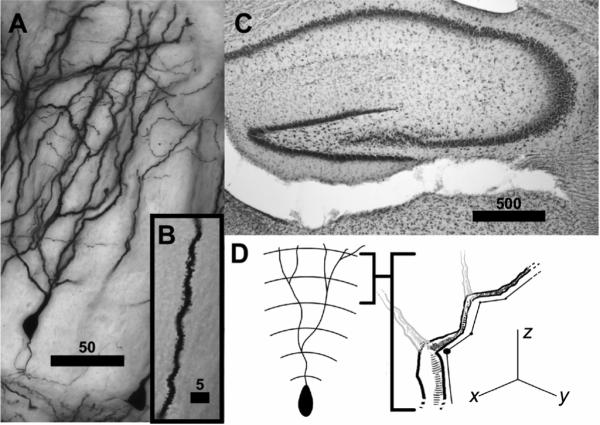

Brain sections containing dentate gyrus and corresponding to plates 26−29 in the Stereotaxic Atlas of the Golden Hamster Brain (Morin and Wood, 2001) were used to create a sample of dentate gyrus neurons. Figure 1 shows Golgiimpregnated (A, B) and thionin- stained (C) neurons in this region of the dentate gyrus. At a low magnification, the boundaries of the dentate gyrus were defined, and neurons were identified for tracing. These candidate neurons were completely impregnated with Golgi stain and overlapped minimally with other stained cells. Most terminal dendritic fields ended within the section (i.e. were not cut by the knife during sectioning). Neurons that met staining criteria were traced using a 60X oil objective, a computerized stage, and Neurolucida software (Ver. 6.50.1, Microbrightfield, Inc., Williston, VT). Tracings were quantified from a total of 112 neurons distributed across the three age groups (P21: n=27; P35: n=41, P49: n=44). The final sample included 1−6 neurons from each hemisphere and 5−10 neurons per individual (X ± SD, 8.00 ± 1.66 neurons/subject).

Figure 1.

A) Image of Golgi-impregnated granule cell from the upper blade of the dentate gyrus. This image has been flattened through multiple planes of focus using a minimum density projection. B) Inset photomicrograph of dendritic spines in granule cell neurons. C) Photomicrograph of Nissl stained tissue, showing the upper and lower blade of the dentate gyrus. Bars in photomicrographs are scaled in μm. D) Schematic of sholl analysis and measurements of dendritic length of Golgi impregnated neurons in x, y, and z planes. Neuroexplorer places these 3 dimensional tracings within concentric spheres at 25 μm intervals originating at the cell body and measures the dendritic length within each sphere and the dendritic intersections with each sphere.

For each neuron, a Sholl analysis measured dendritic length and dendritic intersections. In Sholl analysis, concentric spheres are placed at 25 μm intervals from the cell body. The number of times the dendrite intersected each sphere and the total dendritic length within each sphere was quantified (Figure 1D, data generated from tracings by NeuroExplorer, Version 3.70.2, Microbrightfield, Inc., Williston, VT). Dendritic length was summed across distance in the x, y, and z, planes and across multiple dendritic branches of the neuron that are contained within each radius (Figure 1D). Thus, total dendritic length within a given Sholl radius may exceed the distance of the radius from the soma and may be either smaller or larger than in adjacent Sholl radius measurements. In addition, we quantified for each neuron the number of primary branches, total dendritic length, number of branch points, and the length of the soma (Clairborne et al., 1990; Bartesaghi et al., 2003). Spine density analysis was conducted on a randomly selected subset of 1−3 neurons. Within this subset of neurons, proximal and terminal spine densities were quantified at high magnification using a 100X oil objective. For these neurons, 1−3 distal and proximal dendritic segments were randomly chosen for spine density measurements, and spine density was measured in approximately 20 microns of the segment. Measurements of spine density were then averaged to create a single measure of distal and proximal spine density for each neuron. Of 82 neurons selected for spine density analysis, proximal spine densities were obtained for 80 neurons, and terminal spine densities were obtained for 75 neurons.

Traced neurons were located in both the upper and lower blades of the dentate gyrus, and neurons from males of different ages were equally likely to come from the two blades (N=112, χ2(2)=2.94, n.s.). Previous studies have found some structural differences based on a cell's location within the granule cell layer (e.g. Juraska et al., 1985; Redila & Christie, 2006). In particular, neurons located deep within the granule cell layer are thought to be younger and have fewer primary dendrites. Neurons located superficially within the granule cell layer are thought to be older and are more likely to have multiple primary dendrites. Neurons in this sample were located throughout the entire granule cell layer. Neurons from males of different ages were equally likely to come from superficial and deep granule cell layers (N=112, χ2(2)=0.715, n.s.). As in a previous study (Clairborne et al., 1990), the present study replicated differences in the number of primary dendrites and found no differences in total dendritic length in neurons from superficial and deep layers (data not shown). Furthermore, superficial and deep neurons did not differ significantly in the dependent measures analyzed in this study, including Sholl analysis of dendritic length and intersections, proximal and distal spine densities, soma size, and branch points (data not shown). Thus, superficial and deep neurons were analyzed together.

Statistics

Measures from traced neurons in the upper and lower blade were averaged separately for each subject. For measures of dendritic length and dendritic intersections, a mixed factors analysis of variance (ANOVA) tested for the effects of age (pre-, mid-, or late- adolescence, between subjects variable) and distance from the cell body (Sholl radius, repeated measures variable). Simple comparisons of age at each Sholl radius were used to follow up significant interactions (Keppel, 1991). For the other variables of neuron structure (spine densities, total length, primary number, soma size, and branch points), a single factor ANOVA tested for age (pre-, mid-, or late- adolescence) effects. Significant differences in measures of neuron structure were followed up with a Fisher's LSD post hoc analysis (Keppel, 1991). For all analyses, a p≤0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Sholl Analysis

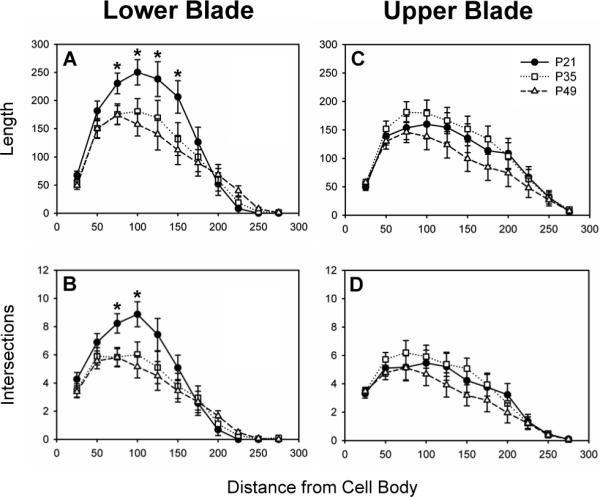

Sholl analysis showed that dendritic structure varied significantly with age in the lower blade but not in the upper blade. Figure 2 illustrates the Sholl analysis of dendritic length (upper graphs) and dendritic intersections (bottom graphs) in the lower and upper blades (left and right graphs respectively). In the lower blade, neurons from 21 day old males had significantly more dendritic length between Sholl radii 75−150 than did neurons from 49 day old males (Figure 2A, Age: F(2,10)=2.001, n.s.; Radius: F(10,100)=83.292, p<0.001; Interaction: F(20,100)=2.741, p<0.001). Similarly, neurons from 21 day old males had significantly more dendritic intersections at Sholl radii 75 and 100 than did neurons from 35 and 49 day old males (Figure 2B, Age: F(2,10)=1.793, n.s.; Radius: F(10,100)=79.107, p<0.001; Interaction: F(20,100)=2.379, p<0.005). In the upper blade, Sholl analysis of dendritic length and intersections did not differ across the three age groups (Length: Figure 2C, Age: F(2,11)<1, n.s.; Radius: F(10,110)=75.088, p<0.001; Interaction: F(20,110)=1.090, n.s.; Intersections: Figure 2D, Age: F(2,11)<1, n.s.; Radius: F(10,110)=77.769, p<0.001; Interaction: F(20,110)=1.107, n.s.). .

Figure 2.

Dendritic length and intersections in neurons from 21, 35, and 49 day old male hamsters located in the lower and upper blades of the dentate gyrus. In the lower blade, dendritic length (A) and intersections (B) were significantly greater in neurons from 21 day old males at Sholl radii between 75 and 150 μm from the cell body. In the upper blade, neither dendritic length (C) nor intersections (D) differed in neurons from 21, 35, and 49 day old males. Panels plot mean ± SEM in μm for dendritic length and in number per neuron for dendritic intersections. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences between age groups at a Sholl radius.

Spine Densities and Measures of Neuron Structure

Distal spine densities varied with age in the lower blade. Specifically, distal spine densities were significantly higher in neurons from 49 day old males (17.36 ± 0.67 spines per 10 μm) than in neurons from 21 day old males (12.76 ± 1.39 spines per 10 μm) or 35 day old males (14.19 ± 0.76 spines per 10 μm) Age: F(2,11)=7.43, p<0.01). Distal spine densities in the upper blade did not vary with age, nor did proximal spine densities vary with age in either blade (Table 1). In both the lower and upper blade, measures of neuron structure, including total dendritic length, the number of primary dendrites, soma size, and the number of branch points did not vary in males of different ages (Table 1).

Table 1.

Measures of dentate gyrus neuron structure that did not differ by age in the upper and lower blades.

| Measure | Blade | P21 Mean ± SEM | P35 Mean ± SEM | P49 Mean ± SEM | Age F(df,df) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distal Spine Densitya | Upper | 17.83 ± 0.14 | 17.41 ± 0.39 | 18.16 ± 0.52 | <1(2,11) |

| Proximal Spine Densitya | Upper | 8.24 ± 1.20 | 11.17 ± 0.71 | 8.83 ± 0.96 | 2.73(2,13) |

| Lower | 6.91 ± 2.99 | 7.59 ± 1.24 | 6.81 ± 0.83 | <1(2,11) | |

| Primary Branchesb | Upper | 1.65 ± 0.27 | 2.00 ± 0.14 | 1.90 ± 0.11 | 1.06(2,13) |

| Lower | 1.75 ± 0.43 | 1.59 ± 0.07 | 1.58 ± 0.12 | <1(2,12) | |

| Total Dendritic Lengthc | Upper | 1123.29 ± 184.03 | 1226.73 ± 126.31 | 938.12 ± 203.09 | <1(2,13) |

| Lower | 1360.11 ± 51.05 | 1044.64 ± 166.52 | 989.91 ± 155.15 | 2.00(2,12) | |

| Branch Pointsb | Upper | 6.58 1.13 | 7.11 ± 0.22 | 4.90 ± 1.10 | 1.78(2,13) |

| Lower | 8.31 ± 0.62 | 6.76 ± 0.75 | 6.92 ± 0.50 | 1.81(2,12) | |

| Soma Sizec | Upper | 17.11 ± 0.72 | 16.84 ± 0.91 | 15.64 ± 0.69 | <1(2,13) |

| Lower | 16.82 ± 0.38 | 16.48 ± 0.55 | 16.63 ± 0.67 | <1(2,12) |

Number per 10 μm

Number per neuron

μm per neuron.

DISCUSSION

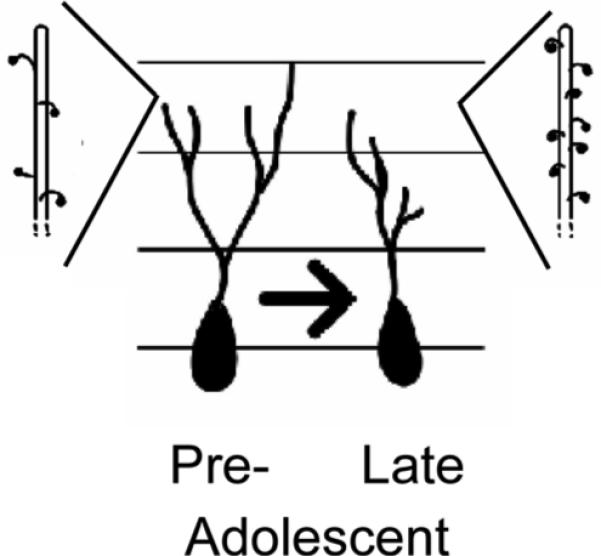

Dentate gyrus neurons exhibit a remarkable, reciprocal interaction between structure and function. The present study demonstrates that, during adolescence, fundamental structural features of dentate gyrus granule cells, including dendritic elaboration and dendritic spines, are remodeled in ways that likely alter cell excitability. Figure 3 summarizes the structural changes observed in neurons from pre-, mid-, and late- adolescent males. Development of neuron structure differed in the upper and lower blades, supporting previous studies that have demonstrated distinct neuroanatomical structure, connections, and functions for these two subregions of the dentate gyrus (Ambrogini et al., 2002; Scharfman et al., 2002; Bartesaghi et al., 2003; Fevurly & Spencer, 2004; Chawla et al., 2005). Specifically, we found no measurable structural modifications to dendrites of neurons in the upper blade, whereas in lower blade neurons, we found evidence of both dendritic pruning and selective synapse proliferation in distal dendritic segments across adolescent development. These developmental changes in neuron structure are likely associated with adolescent changes in spatial cognition, learning and memory, and stress responses.

Figure 3.

Summary of adolescent changes in neuron structure within the lower blade of the dentate gyrus. Dendritic length decreased ∼ 75 to 150 μm from the cell body and terminal spine densities increased during adolescence in these neurons.

This study provides an important complement to the existing literature on hippocampal development during adolescence. The decreases in dendritic length and intersections in Sholl radii close to the cell body between pre- and mid-adolescent male hamsters in our study are consistent with the developmental changes during the juvenile period in male guinea pigs (Bartesaghi et al., 2003). It is possible that the developmental window between 21 and 35 days in hamsters may overlap with the developmental window between 15 and 45 days in guinea pigs. Further study encompassing more developmental periods in a variety of species are necessary to provide a comparative perspective on the development of dentate gyrus neuron structure across the lifespan.

Spine density, a second measure of dendritic elaboration, varies both with age and with circulating hormone levels in the hippocampus. This study demonstrated that, as in male mice (Meyer et al., 1978), spine densities increase during adolescence in dentate gyrus neurons. However, this study also showed that these increases are specific to distal segments in the lower blade. In contrast to our findings, distal spine densities in the lower blade decreased from the neonatal to prepubertal period in male guinea pigs (Bartesaghi et al., 2003), suggesting either that the timing of developmental changes in spine density are species-specific and may differ between precocial and altricial species, or that neuronal maturation during the juvenile and adolescent periods are qualitatively distinct. Spine densities also increase during adolescence in CA1, presumably resulting from increases in circulating testosterone (Meyer et al., 1978; MacLusky et al., 2006; Cunningham et al., 2007). In contrast, CA1 spine densities decrease during adolescence in female rats (Yildirim et al., in press). Taken together, there appears to be region, sex, and/or species specificity to adolescent maturation of the hippocampus.

Because the upper blade is so closely tied to physiological and behavioral changes occurring during adolescence (e.g. stress responsivity and spatial ability), and because of the high concentration of androgen receptor, we predicted that the upper blade would display a high degree of morphological change. Contrary to our prediction, the upper blade had no age-related changes in neuron structure. In contrast, the lower blade showed age-related changes in dendritic measures of neuron structure. Pruning of dendritic content close to the cell body occurred during early adolescence, as neurons from 21 day old males had significantly more dendritic length and more dendritic intersections ∼ 75 to 150 μm from the cell body than did neurons from 35 or 49 day old males. In contrast to the decrease in proximal dendrites, there was an increase in spine densities in distal dendritic segments. Neurons from 49 day old males had significantly higher dendritic spine densities in distal segments than did neurons from younger males. The inner molecular layer receives diverse inputs from regions including the hillus, entorhinal cortex, and the medial septum/diagonal band, and the outer molecular layer receives inputs primarily from the entorhinal cortex (reviewed in Lübbers & Frotscher, 1987; Leranth & Hajszan, 2007). Within the context of this laminar organization, the pruning of dendritic fields close to the granule cell layer and the increases in spine density on distal segments suggest that the relative influence of different afferent inputs may change during adolescent development.

The different developmental patterns observed in the upper and lower blade contradicted our predictions and are particularly interesting in light of functional differences between the blades. We had predicted that the upper blade would have more age-related changes in neuron structure based on its activation in hippocampal dependent functions which mature during adolescence. The upper blade is activated more than the lower blade by both spatial tasks (Chawla et al., 2005) and exposure to a stressor (Fevurly & Spencer, 2004). The more dramatic developmental changes in morphology observed in the lower blade seem at odds with the developmental changes in spatial cognition and stress responses, which are tied to activation of neurons in the upper blade. Because the geometry of dendrites directly affects the integration and propagation of changes in membrane potential (Mainen & Sejnowski, 1996), adolescent changes in neuron structure will impact cell firing characteristics and are thus likely to modify hippocampal function.

One important caveat to this study is that the stress associated with shipping may have altered the development of neuron structure in dentate gyrus. In this study, all males were obtained from commercial breeders at 18 days of age and incurred the stress associated with this travel (Capdevila et al., 2007). Subjects were shipped with an adult female to help ameliorate this stress, and indeed, rodents tolerate aversive stimuli better when housed with conspecifics (Sharp et al., 2002). In the CA3 region of the hippocampus, stress can induce decreases in the length of apical dendrites and decreases in soma size (Woolley et al., 1990; Nishi et al., 2007). However, in these same studies, the dentate gyrus did not respond to stress or increased glucocorticoids with measurable changes in neuron structure (Woolley et al., 1990; Nishi et al., 2007). Instead, glucocorticoids maintain dendritic structure in the dentate gyrus (Gould et al., 1990a), and stress acts on the dentate gyrus to decrease rates of neurogenesis (Cameron & Gould, 1994). Thus, although the dentate gyrus is sensitive to glucocorticoids, it is unlikely that the stress of shipping is responsible for the effects observed in this study. Additional studies would be needed to empirically test whether early adolescent stressors such as shipping or weaning differentially affect the development of neuron structure in the two blades of the dentate gyrus.

Although not explicitly tested in this study, pubertal increases in gonadal hormones may contribute to adolescent structural changes in dentate gyrus neurons. In this study proximal dendritic length decreased in the lower blade while distal spine densities increased. Most regions of the hippocampus are steroid-responsive (McCarthy & Konkle, 2005), and previous studies report trophic effects of gonadal hormones on synaptic plasticity, with greater spine densities in gonad intact males compared with castrates (Meyer et al., 1978; Leranth et al., 2003) and on proestrus in females, a day of high circulating estrogen in the rodent ovarian cycle (Gould et al., 1990b; Woolley & McEwen, 1992; see also review by Cooke & Woolley, 2005). If the patterns of developmental change observed in this study are dependent on steroid hormones, it would suggest that steroids do not exert a blanket trophic effect but rather exert specific effects in functionally distinct regions of neurons. Steroids may also influence dentate gyrus morphology indirectly by acting on connections to these neurons. More specifically, steroids acting on afferent neurons could account indirectly for both trophic and regressive influences on neuron morphology within the lower blade. Alternatively, adolescent changes in neuron structure may be steroid independent. Age-related changes in neuron structure occurred in the lower blade, which has fewer gonadal steroid hormone receptors (Kerr et al., 1995; Weiland et al., 1997). The lower blade is also less responsive to glucocorticoids and corticosterone (Gould et al., 1990a; Ambrogini et al., 2002), which also increase around this developmental period (Pignatelli et al., 2006). Thus, additional studies that directly manipulate steroid hormones during adolescence are needed to determine whether the maturation of dentate gyrus neuron structure is steroid-dependent.

The dentate gyrus is a unique region of the hippocampus because it exhibits high levels of adult neurogenesis. New neurons are produced in the dentate gyrus throughout life, and neurogenesis is higher in periadolescent rats than in post-adolescent rats (Kim et al., 2004; He & Crews, 2007). Neurons born late in postnatal life project axons within a few days (Cameron et al., 1993) and become functionally integrated within a few weeks, as evidenced by activation of these cells during spatial tasks (Shors et al., 2001; van Praag et al., 2002; Jessberger & Kempermann, 2003). The adolescent changes in neuron structure observed in this study could also result from a gradual replacement of neurons with a ‘juvenile’ structure by neurons with an ‘adult’ structure. Specifically, the high turnover of neurons in the dentate gyrus may remove neurons with a juvenile pattern of dendritic elaboration as new neurons with an adult pattern of dendritic elaboration grow and are established within the region. In guinea pigs, the direction of sex differences in some aspects of dendritic morphology observed in dentate gyrus neurons reverses between early juvenile and prepubertal ages (Bartesaghi et al., 2003), suggesting that age-specific programming of neuron structure is theoretically possible. Alternatively, the constant addition of new neurons may drive new patterns of dendritic elaboration as the dentate gyrus accommodates the growth of new neuronal processes. For example, while there is pruning of proximal dendrites and spines within individual neurons, the total number of proximal synaptic connections may remain constant, with newly added neurons receiving input previously received by older neurons. Since the high rate of neurogenesis is accompanied by a high rate of cell death in this region, there are multiple mechanisms through which dendritic elaboration, spine densities, and regional connectivity of dentate gyrus neurons can be remodeled through adolescence and the lifespan.

In summary, this study demonstrates developmental changes in the structure of dentate gyrus granule cells. The dendrites of granule cells in the lower blade of the dentate gyrus are pruned proximal to the cell body, but showed an increase in distal spine densities, indicating functional changes in the processing of synaptic input. These developmental changes in neuron structure may be responsible in part for maturational changes in hippocampal-dependent functions such as spatial cognition, environment-related social interactions, and responses to stress.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the members of the Sisk laboratory for their valuable discussions of data analysis and early versions of this manuscript. Illustrations in Figures 1 and 3 drawn by Stephen Thomas. Research was supported by F32-MH068975 (JLZ), F31-MH070125 (KMS), and R01-MH068764 (CLS).

REFERENCES

- Abrous DN, Koehl M, Le Moal M. Adult neurogenesis: from precursors to network and physiology. Physiol Rev. 2005;85(2):523–69. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00055.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrogini P, Orsini L, Mancini C, Ferri P, Barbanti I, Cuppini R. Persistently high corticosterone levels but not normal circadian fluctuations of the hormone affect cell proliferation in the adult rat dentate gyrus. Neuroendocrinology. 2002;76(6):366–72. doi: 10.1159/000067581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartesaghi R, Serrai A. Effects of early environment on granule cell morphology in the dentate gyrus of the guinea-pig. Neuroscience. 2001;102(1):87–100. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00446-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartesaghi R, Guidi S, Severi S, Contestabile A, Ciani E. Sex differences in the hippocampal dentate gyrus of the guinea-pig before puberty. Neuroscience. 2003;121(2):327–39. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00434-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer SA. Development of the hippocampal region in the rat. II. Morphogenesis during embryonic and early postnatal life. J Comp Neurol. 1980;190(1):115–34. doi: 10.1002/cne.901900108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, Gould E. Adult neurogenesis is regulated by adrenal steroids in the dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 1994;61(2):203–9. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, Woolley CS, McEwen BS, Gould E. Differentiation of newly born neurons and glia in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat. Neuroscience. 1993;56(2):337–44. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90335-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila S, Giral M, Ruiz de la Torre JL, Russell RJ, Kramer K. Acclimatization of rats after ground transportation to a new animal facility. Lab Anim. 2007;41(2):255–61. doi: 10.1258/002367707780378096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla MK, Guzowski JF, Ramirez-Amaya V, Lipa P, Hoffman KL, Marriott LK, Worley PF, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA. Sparse, environmentally selective expression of Arc RNA in the upper blade of the rodent fascia dentata by brief spatial experience. Hippocampus. 2005;15(5):579–86. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clairborne BJ, Amaral DG, Cowan WM. Quantitative, three-dimensional analysis of granule cell dendrites in the rat dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302:206–219. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke BM, Woolley CS. Gonadal hormone modulation of dendrites in the mammalian CNS. J Neurobiol. 2005;64(1):34–46. doi: 10.1002/neu.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham RL, Claiborne BJ, McGinnis MY. Pubertal exposure to anabolic androgenic steroids increases spine densities on neurons in the limbic system of male rats. Neuroscience. 2007;150(3):609–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faherty CJ, Kerley D, Smeyne RJ. A Golgi-Cox morphological analysis of neuronal changes induced by environmental enrichment. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;141(1−2):55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00642-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fevurly RD, Spencer RL. Fos expression is selectively and differentially regulated by endogenous glucocorticoids in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and the dentate gyrus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16(12):970–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2004.01257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea LA, Ossenkopp KP, Kavaliers M. Developmental changes in spatial learning in the Morris water-maze in young meadow voles, Microtus pennsylvanicus. Behav Brain Res. 1994;60(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Clasen LS, Lenroot R, Greenstein D, Wallace GL, Ordaz S, Molloy EA, Blumenthal JD, Tossell JW, Stayer C, Samango-Sprouse CA, Shen D, Davatzikos C, Merke D, Chrousos GP. Puberty-related influences on brain development. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;254−255:154–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez DM, Newman SW. Medial nucleus of the amygdala in the adult Syrian hamster: a quantitative Golgi analysis of gonadal hormonal regulation of neuronal morphology. Anat Rec. 1991;231(4):498–509. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092310412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Short-term glucocorticoid manipulations affect neuronal morphology and survival in the adult dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 1990a;37(2):367–75. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90407-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Woolley CS, Frankfurt M, McEwen BS. Gonadal steroids regulate dendritic spine density in hippocampal pyramidal cells in adulthood. J Neurosci. 1990b;10(4):1286–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-04-01286.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidi S, Severi S, Ciani E, Bartesaghi R. Sex differences in the hilar mossy cells of the guinea-pig before puberty. Neuroscience. 2006;139(2):565–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Crews FT. Neurogenesis decreases during brain maturation from adolescence to adulthood. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:327–33. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbard PC, King RR, Malsbury CW, Harley CW. Two organizational effects of pubertal testosterone in male rats: transient social memory and a shift away from long-term potentiation following a tetanus in hippocampal CA1. Exp Neurol. 2003;182(2):470–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodes GE, Shors TJ. Distinctive stress effects on learning during puberty. Horm Behav. 2005;48(2):163–71. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessberger S, Kempermann G. Adult-born hippocampal neurons mature into activity-dependent responsiveness. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18(10):2707–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.02986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junier MP. What role(s) for TGFalpha in the central nervous system? Prog Neurobiol. 2000;62(5):443–73. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juraska JM, Fitch JM, Henderson C, Rivers N. Sex differences in the dendritic branching of dentate granule cells following differential experience. Brain Res. 1985;333(1):73–80. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanit L, Taskiran D, Yilmaz OA, Balkan B, Demirgoren S, Furedy JJ, Pogun S. Sexually dimorphic cognitive style in rats emerges after puberty. Brain Res Bull. 2000;52(4):243–8. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel G. Design and Analysis: A Researcher's Handbook. 3rd Edition Prentice Hall; New Jersey: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr JE, Allore RJ, Beck SG, Handa RJ. Distribution and hormonal regulation of androgen receptor (AR) and AR messenger ribonucleic acid in the rat hippocampus. Endocrinology. 1995;136(8):3213–21. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.8.7628354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YP, Kim H, Shin MS, Chang HK, Jang MH, Shin MC, Lee SJ, Lee HH, Yoon JH, Jeong IG, Kim CJ. Age-dependence of the effect of treadmill exercise on cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus of rats. Neurosci Lett. 2004;355(1−2):152–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshibu K, Levitt P, Ahrens ET. Sex-specific, postpuberty changes in mouse brain structures revealed by three-dimensional magnetic resonance microscopy. Neuroimage. 2004;22(4):1636–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshibu K, Ahrens ET, Levitt P. Postpubertal sex differentiation of forebrain structures and functions depend on transforming growth factor-alpha. J Neurosci. 2005;25(15):3870–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0175-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenroot RK, Giedd JN. Brain development in children and adolescents: insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30(6):718–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leranth C, Petnehazy O, MacLusky NJ. Gonadal hormones affect spine synaptic density in the CA1 hippocampal subfield of male rats. J Neurosci. 2003;23(5):1588–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01588.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leranth C, Hajszan T. Extrinsic afferent systems to the dentate gyrus. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:63–84. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lübbers K, Frotscher M. Fine structure and synaptic connections of identified neurons n the rat fascia dentata. Anat Embryol. 1987;177(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00325285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuner B, Gould E, Shors TJ. Is there a link between adult neurogenesis and learning? Hippocampus. 2006;16(3):216–24. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLusky NJ, Hajszan T, Prange-Kiel J, Leranth C. Androgen modulation of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuroscience. 2006;138(3):957–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainen ZF, Sejnowski TJ. Influence of dendritic structure on firing pattern in model neocortical neurons. Nature. 1996;382(6589):363–6. doi: 10.1038/382363a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Konkle AT. When is a sex difference not a sex difference? Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26(2):85–102. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Ferres-Torres R, Mas M. The effects of puberty and castration on hippocampal dendritic spines of mice. A Golgi study. Brain Res. 1978;155(1):108–12. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LL, Whitsett JM, Vandenbergh JG, Colby DR. Physical and behavioral aspects of sexual maturation in male golden hamsters. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1977;91(2):245–59. doi: 10.1037/h0077315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin LP, Wood RI. Stereotaxic Atlas of the Golden Hamster Brain. Academic Press; USA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nishi M, Usuku T, Itose M, Fujikawa K, Hosokawa K, Matsuda KI, Kawata M. Direct visualization of glucocorticoid receptor positive cells in the hippocampal regions using green fluorescent protein transgenic mice. Neuroscience. 2007;146(4):1555–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignatelli D, Xiao F, Gouveia AM, Ferreira JG, Vinson GP. Adrenarche in the rat. J Endocrinol. 2006;191(1):301–8. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primus RJ, Kellogg CK. Pubertal-related changes influence the development of environment-related social interaction in the male rat. Dev Psychobiol. 1989;22(6):633–43. doi: 10.1002/dev.420220608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redila VA, Christie BR. Exercise-induced changes in dendritic structure and complexity in the adult hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 2006;137(4):1299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RD, Lee SJ, Chhua N, McPherson CR, McEwen BS. Testosterone cannot activate an adult-like stress response in prepubertal male rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;79(3):125–32. doi: 10.1159/000077270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, Sollas AL, Smith KL, Jackson MB, Goodman JH. Structural and functional asymmetry in the normal and epileptic rat dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 2002;454(4):424–39. doi: 10.1002/cne.10449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp JL, Zammit TG, Azar TA, Lawson DM. Stress-like responses to common procedures in male rats housed alone or with other rats. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2002;41(4):8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ. Stressful experience and learning across the lifespan. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:55–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ, Miesegaes G, Beylin A, Zhao M, Rydel T, Gould E. Neurogenesis in the adult is involved in the formation of trace memories. Nature. 2001;410(6826):372–6. doi: 10.1038/35066584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisk CL, Turek FW. Developmental time course of pubertal and photoperiodic changes in testosterone negative feedback on gonadotropin secretion in the golden hamster. Endocrinology. 1983;112(4):1208–16. doi: 10.1210/endo-112-4-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisk CL, Zehr JL. Pubertal hormones organize the adolescent brain and behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26(3−4):163–74. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Schinder AF, Christie BR, Toni N, Palmer TD, Gage FH. Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Nature. 2002;415(6875):1030–4. doi: 10.1038/4151030a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiland NG, Orikasa C, Hayashi S, McEwen BS. Distribution and hormone regulation of estrogen receptor immunoreactive cells in the hippocampus of male and female rats. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388(4):603–12. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971201)388:4<603::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, Gould E, McEwen BS. Exposure to excess glucocorticoids alters dendritic morphology of adult hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Brain Res. 1990;531(1−2):225–31. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90778-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Estradiol mediates fluctuation in hippocampal synapse density during the estrous cycle in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 1992;12(7):2549–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02549.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim M, Mapp OM, Janssen WG, Yin W, Morrison JH, Gore AC. Postpubertal decrease in hippocampal dendritic spines of female rats. Exp Neurol. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.11.003. In press. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehr JL, Todd BJ, Schulz KM, McCarthy MM, Sisk CL. Dendritic pruning of the medial amygdala during pubertal development of the male Syrian hamster. J Neurobiol. 2006;66(6):578–90. doi: 10.1002/neu.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]