Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is a growing problem in all parts of the world. Both clinical trials and animal models of type I and type II diabetes have shown that hyperactivity of angiotensin-II (Ang-II) signaling pathways contribute to the development of diabetes and diabetic complications. Of clinical relevance, blockade of the renin–angiotensin system prevents new-onset diabetes and reduces the risk of diabetic complications. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 2 is a recently discovered mono-carboxypeptidase and the first homolog of ACE. It is thought to inhibit Ang-II signaling cascades mostly by cleaving Ang-II to generate Ang-(1–7), which effects oppose Ang-II and are mediated by the Mas receptor. The enzyme is present in the kidney, liver, adipose tissue and pancreas. Its expression is elevated in the endocrine pancreas in diabetes and in the early phase during diabetic nephropathy. ACE2 is hypothesized to act in a compensatory manner in both diabetes and diabetic nephropathy. Recently, we have shown the presence of the Mas receptor in the mouse pancreas and observed a reduction in Mas receptor immuno-reactivity as well as higher fasting blood glucose levels in ACE2 knockout mice, indicating that these mice may be a new model to study the role of ACE2 in diabetes. In this review we will examine the role of the renin–angiotensin system in the physiopathology and treatment of diabetes and highlight the potential benefits of the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas receptor axis, focusing on recent data about ACE2.

Keywords: Diabetes, Renin–angiotensin system, Glucose homeostasis, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, Beta cell dysfunction

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is characterized by insulin insufficiency due to either decreased insulin release or end-organ insulin resistance. Several major categories of diabetes exist, type I (T1DM) and type II (T2DM) diabetes, gestational diabetes and maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY). T1DM usually occurs in children and young adults and is characterized by pancreatic β-cell failure or auto-immune destruction of the pancreatic β-cells. T2DM is characterized by insulin resistance and relative insulin insufficiency with adult onset. Risk factors for T2DM include family history, hypertension, obesity and dyslipidemia. MODY is characterized by specific defects in glucose metabolism.

Diabetes currently affects more than 135 million people worldwide. The number of diabetics is expected to grow to 300 million by the year 2025, which will represent approximately a 42 and 170% increases in the prevalence of diabetes in developed and developing countries, respectively (King et al., 1998). In addition to a rise in diabetes among adults, childhood T2DM is also expected to rise due to due to increasing childhood obesity (Dabelea et al., 1999, Pinhas-Hamiel and Zeitler, 2005). Although until recently non-immune-mediated diabetes was rare in children, the American Diabetes Association recently reported a rise in the number of children with new diagnoses of such disease, the majority of whom have T2DM (Anonymous, 2000b). Indeed, a rise in childhood T2DM has been observed across many ethnic groups including Native Americans (Dabelea et al., 1998), Hispanics (Neufeld et al., 1998), African-Americans (Dabelea et al., 1999) and Caucasians (Drake et al., 2002, Ehtisham et al., 2000).

Diabetes is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, and diabetics are at increased risk for development of hypertension, myocardial infarction, renal disease and stroke (Grundy et al., 1999). Thus, the global increase in diabetes is a public health crisis which requires new prevention and treatment tools.

2. Tissue renin–angiotensin system (RAS) and metabolism

The classical renin–angiotensin system consists of liver-generated angiotensinogen being cleaved by renin, generated in the kidney, to produce angiotensin-I (Ang-I). Ang-I is subsequently hydrolyzed by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) to produce angiotensin-II (Ang-II), which promotes vasoconstriction, inflammation, salt and water reabsorption and oxidative stress. Two decades ago, the concept of local tissue RAS was introduced following the observation that many tissues are capable of synthesizing a majority of the RAS components locally (Dzau and Re, 1994, Lavoie and Sigmund, 2003).

2.1. Effect of the RAS on metabolic organs

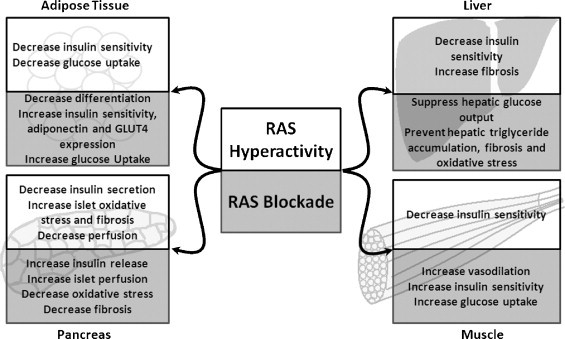

The existence of a local RAS has been confirmed in many tissues, including the heart (Danser and Schalekamp, 1996), vasculature (Paul et al., 2006), brain (Baltatu et al., 2000), retina (Tikellis et al., 2000a) liver (Bataller et al., 2003, Paizis et al., 2002) and pancreas (Lau et al., 2004). The local RAS influences the function of the metabolic organs and the development of diabetes (Fig. 1 ). Expression of ACE, the Ang-II type 1 (AT1) receptor and renin have been identified in the liver by quantitative RT-PCR (Paizis et al., 2002) and protein expression confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Paizis et al., 2002). Ang-II type 2 (AT2) receptor expression has been reported in stellate cells (Bataller et al., 2003), although this could not be confirmed by other groups (Paizis et al., 2002). Studies involving RAS blockade in the setting of diabetes have given some clues to the potential role of the intra-hepatic RAS in the pathogenesis of diabetes. RAS blockade prevents hepatic triglyceride accumulation in obese Zucker rats, a common feature of insulin resistant and diabetic states (Toblli et al., 2007). Additionally, enalapril prevents fibrosis and oxidative stress in the liver, heart and kidney of rats with T1DM (de Cavanagh et al., 2001). The most remarkable evidence for the role of the RAS in diabetes is the demonstration that captopril suppressed hepatic glucose output and increased hepatic glucose uptake in response to insulin infusion (Torlone et al., 1991).

Fig. 1.

The role of the RAS in metabolic organ function. Ang-II signaling cascades inhibit insulin release and decrease insulin sensitivity. RAS blockade improves glucose homeostasis by reducing β-cell death and improving insulin secretion and end-organ insulin sensitivity.

RAS components have been identified in both the endocrine and exocrine pancreas. Angiotensinogen, renin, AT1 and AT2 receptors, ACE and ACE2 proteins are all expressed in this organ (Tikellis et al., 2004b, Leung et al., 1999, Chappell et al., 1991, Carlsson, 2001, Leung et al., 1998). Additionally, AT1 receptor protein expression is limited to the pancreatic β-cell (Tahmasebi et al., 1999). While pro-renin mRNA expression was identified by in situ hybridization in the reticular fibers of the islets and perivascular connective tissue, immuno-staining revealed that islet pro-renin protein primarily exists in the β-cells (Tahmasebi et al., 1999). Several studies have demonstrated activation of the islet RAS in diabetic animals (Leung, 2007, Tikellis et al., 2004b).

Maintenance of islet perfusion is important in the regulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) (Tikellis et al., 2006) and a potential role for the pancreas RAS has been suggested in the maintenance of islet blood flow (Leung, 2007). Supporting evidence include: (1) greater Ang-II levels in islet microvessels compared to exocrine pancreas microvessels (Carlsson et al., 1998); (2) acute Ang-II infusion decreases islet blood flow in healthy non-diabetic Sprague–Dawley rats (Carlsson et al., 1998); and (3) RAS blockade by ACE inhibitors or AT1 receptor blockers preferentially increased blood flow to islet microvessels (Carlsson et al., 1998).

Another role of the islet RAS is in the modulation of β-cell function. Insulin release occurs in two phases, the first phase appearing within 10–15 min after stimulus and peaking at 3 min (Curry et al., 1968). In non-diabetic rats, acute Ang-II infusion prevented the first phase insulin secretion in response to glucose (Carlsson et al., 1998), and in healthy human subjects, pressor doses of Ang-II suppressed basal, pulsatile and glucose-stimulated insulin release (Fliser et al., 1997). This loss of first phase insulin secretion is hypothesized to be the earliest detectable defect in the development of T2DM (Gerich, 2002).

2.2. Pancreatic RAS and oxidative stress

Although RAS inhibition has no effect on basal insulin secretion (Carlsson et al., 1998), it may improve insulin synthesis and secretion by protecting β-cells from oxidative stress-related tissue damage and loss of insulin secretion. Pancreatic islets express lower levels of antioxidants than the majority of other tissues in the body (Grankvist et al., 1981), which makes them especially vulnerable to oxidative stress (Evans et al., 2002). Several studies indicate that hyperglycemia produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) in islets and pancreatic β-cells (Wu et al., 2004, Tsubouchi et al., 2004, Tang et al., 2007, Bindokas et al., 2003), as illustrated in the diabetic Zucker rat (Tang et al., 2007). Moreover, oxidative stress induces pancreatic β-cell dysfunction (Robertson, 2004, Matsuoka et al., 1997, Maechler et al., 1999, Kaneto et al., 2001, Harmon et al., 2005). NAD(P)H oxidase (NOX) is one suggested source of ROS in the islet (Nakayama et al., 2005, Oliveira et al., 2003, Tsubouchi et al., 2004). NOX activation is triggered by interaction of Ang-II with the AT1 receptor (Griendling et al., 1994) and requires the assembly of the cytosolic subunits p47phox, p40phox and p67phox on the membrane bound scaffold proteins p22phox and Nox2/4 (Harrison et al., 2007). Expression of Nox2 (Oliveira et al., 2003), p22phox (Oliveira et al., 2003), and Nox4 (Uchizono et al., 2006) has been shown in pancreatic β-cells and is further increased in models of T1DM and T2DM (Nakayama et al., 2005, Oliveira et al., 2003, Tsubouchi et al., 2004).

In addition to causing pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and apoptosis, oxidative stress can lead to loss of insulin synthesis and secretion through several mechanisms including loss of transcription factors (e.g. MaFA and Pdx-1) required for insulin gene expression (Matsuoka et al., 1997, Kaneto et al., 2001). Secondly, ROS are implicated in the development of amyloid deposition (Hayden and Tyagi, 2002) and islet fibrosis (Hayden et al., 2007). Both have been linked to the development of β-cell dysfunction and apoptosis (Clark and Nilsson, 2004, Hayden et al., 2007). In agreement with the hypothesis that RAS activation leads to increased islet ROS and fibrosis, Hayden et al. demonstrated that Ren2 rats, with elevated Ang-II accumulation due to renin over-expression (Langheinrich et al., 1996), have elevated islet nitrotyrosine content and fibrosis (Hayden et al., 2007). In addition, islet nitrotyrosine and TGF-β expression co-localize with areas of increased peri-islet fibrosis (Hayden et al., 2007). Enhanced fibrosis of islets and decreased insulin synthesis cumulatively can cause decreased insulin secretion and exacerbate the development of diabetes. RAS blockade has been shown to be effective at reducing oxidative stress-induced changes in islets by inhibiting the expression of the NOX components, p22phox and Nox2 (Nakayama et al., 2005), thus decreasing the expression of oxidative stress markers, including nitrotyrosine (Lupi et al., 2006, Tikellis et al., 2004a, Tikellis et al., 2004b) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal modified protein, a marker of fatty acid oxidation (Nakayama et al., 2005). In addition, RAS blockade has been associated with a decrease in islet AT1 and ACE expression (Tikellis et al., 2004a, Tikellis et al., 2004b), which would result in decreased NOX activation. Moreover, RAS blockade-mediated decreases in the expression of the NOX components p22phox and Nox2 (Shao et al., 2006), and nitrotyrosine levels (Shao et al., 2006, Tikellis et al., 2004b) in the islet were associated with prevention of islet dysfunction and deleterious changes in islet morphology. This was demonstrated by prevention of (1) islet fibrosis (Shao et al., 2006, Tikellis et al., 2004a, Tikellis et al., 2004b), (2) loss of insulin secretion (Lupi et al., 2006, Shao et al., 2006, Tikellis et al., 2004b) and (3) loss of β-cells and reduction in islet insulin content (Shao et al., 2006, Tikellis et al., 2004b, Nakayama et al., 2005), independently of changes in plasma glucose levels. Therefore, hyperactivity of Ang-II signaling cascades is clearly implicated in the development of islet oxidative stress and subsequent β-cell dysfunction.

3. RAS blockade inhibits new onset diabetes: clinical trials evidence

Clinical trials have demonstrated the ability of RAS blockade to prevent new-onset diabetes and the development of diabetic complications. Meta-analysis of several trials demonstrated that ACE inhibitors or Ang-II receptor blockers (ARB) reduced the risk of diabetes by 25% (Abuissa et al., 2005). Interestingly, when compared to diuretic and β-blocker therapies, patients receiving ARB or ACE inhibitors had a 25–30% lower risk of developing new-onset diabetes despite similar reductions in blood pressure (BP) (Anonymous, 2000a, Niklason et al., 2004, Reid et al., 2003, Vermes et al., 2003). Indeed, β-blocker therapy has been shown to increase the risk of developing diabetes (Mason et al., 2005, Gress et al., 2000). These findings indicate that a reduction in BP alone is not sufficient to prevent new onset diabetes and that these effects are likely specific to RAS inhibition. In addition to the prevention of new-onset diabetes, RAS blockade ameliorates glycemic control in diabetic patients. It reduced glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, a measure of long-term glycemic control (Anonymous, 1998, Yusuf et al., 2001), and reduced the use of oral anti-hyperglycemic agents in diabetics when compared to placebo or conventional therapy (Anonymous, 1998, Yusuf et al., 2001). The ability of RAS blockade to prevent new-onset diabetes and ameliorate glycemic control in diabetic patients combined with its ability to improve islet morphology, insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity provide powerful evidence that the RAS should be a continued target for novel therapeutics in diabetes.

4. ACE2, a new member of the RAS

ACE2 was initially identified from human heart failure and lymphoma cDNA libraries (Donoghue et al., 2000, Tipnis et al., 2000) and was later shown to serve as a receptor for the SARS coronavirus (Li et al., 2003). ACE2 is the first ACE homologue with 42% sequence homology, and unlike ACE, this zinc metalloprotease contains only one HEXXH consensus sequence, resulting in monocarboxy-peptidase activity (Tipnis et al., 2000). In addition, ACE2 also has 48% sequence homology with collectrin, a newly discovered glycoprotein responsible for regulation of renal amino acid transport (Danilczyk et al., 2006, Zhang et al., 2001) and maintenance of collecting duct cell morphology (Zhang et al., 2007). Both proteins share identity in the cytosolic, sheddase, transmembrane and non-catalytic extracellular domains (Zhang et al., 2001). ACE2 exists as both membrane bound and soluble forms (Donoghue et al., 2000, Feng et al., 2008), the latter being generated by proteolytic cleavage of the ectodomain by the tumor necrosis factor convertase, ADAM17 (Lambert et al., 2005). Although ACE2 shares the catalytic domain of ACE, it is not sensitive to ACE inhibitors (Tipnis et al., 2000).

ACE2 substrate specificity has been hypothesized to require a Pro-X-Pro-hydrophobic/basic conformation for proteolytic cleavage (Guy et al., 2003). While the carboxypeptidase is capable of cleaving the terminal leucine from Ang-I to generate Ang-(1–9) (Donoghue et al., 2000), it has approximately a 400-fold greater affinity for Ang-II (Vickers et al., 2002). ACE2 cleaves the terminal phenylalanine residue from Ang-II to generate Ang-(1–7) (Tipnis et al., 2000). Although the enzyme is also capable of complete hydrolysis of des-Arg9-bradykinin, apelin-13, β-casomorphin, neocasomorphin and dynorphin-A, and partial hydrolysis of many biologically active peptides including neurotensin and ghrelin (Vickers et al., 2002), only its effects on angiotensin peptides have been investigated so far.

Since its original detection primarily in human heart, kidneys and testes (Donoghue et al., 2000), ACE2 has been identified in a variety of tissues, including the rat brain (Gallagher et al., 2003), lung (Gembardt et al., 2005), adipose tissue (Gembardt et al., 2005), liver (Paizis et al., 2005), pancreas (Tikellis et al., 2004a) retina (Tikellis et al., 2004b), and human placenta (Valdés et al., 2006), colon, small intestine, ovary (Tipnis et al., 2000), and is thought to be ubiquitously expressed. It has been hypothesized to regulate the RAS by opposing the ACE/Ang-II/AT1 receptor axis, and therefore counter several pathologic processes including cardiac dysfunction (Diez-Freire et al., 2006, Gurley et al., 2006, Yamamoto et al., 2006), hypertension (Diez-Freire et al., 2006, Gurley et al., 2006, Yamazato et al., 2007), acute respiratory distress syndrome (Imai et al., 2008, Imai et al., 2005), inflammation (Huentelman et al., 2005, Paizis et al., 2005, Diez-Freire et al., 2006) and fibrosis (Diez-Freire et al., 2006, Huentelman et al., 2005, Paizis et al., 2005, Herath et al., 2007). While Ang-II has well known vasoconstrictor, pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidant effects, mediated mostly by the AT1 receptor, Ang-(1–7), the primary product of Ang-II degradation by ACE2, acts through the Mas receptor (Santos et al., 2003) to produce vasodilation via activation of bradykinin and nitric oxide (NO) (Oliveira et al., 1999, Brosnihan et al., 1996, Fernandes et al., 2001, Paula et al., 1995, Toblli et al., 2007), release of prostaglandins (Almeida et al., 2000), and inhibition of norepinephrine release (Gironacci et al., 2004). Recent studies have implicated the Akt pathway in Ang-(1–7) mediated NO release (Sampaio et al., 2007). In addition, ACE2 attenuates fibrosis and inflammation through inhibition of TGF-β (Grobe et al., 2007) and macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) (Zhong et al., 2007).

5. ACE2 and diabetes

The study of ACE2 in the context of diabetes has been essentially focused on the kidney. ACE2 may be an important target for the treatment and prevention of diabetic nephropathy, a progressive condition characterized by mesangial matrix expansion, thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, proteinuria, and associated with chronic renal failure. Recently several studies have also implicated podocyte loss (Schmid et al., 2003, Susztak et al., 2006, Dalla Vestra et al., 2003, Meyer et al., 1999, Pagtalunan et al., 1997) and this disappearance is associated with worsening glomerular injury (Yu et al., 2005).

The kidney expresses a fully functional local RAS, capable of producing Ang-II (Bader et al., 2001, Paul et al., 2006), which is activated in hyperglycemic conditions (Konoshita et al., 2006). ACE2 expression has been identified in renal cortical tubules (Ye et al., 2004) and apical border of the proximal convoluted tubules (Ye et al., 2006) in mice, where ACE2 co-localizes with podocyte specific markers (Schmid et al., 2003) nephrin, podocin and synaptopodin. Electron microscopy further confirmed that ACE2 was primarily located in the podocyte (Ye et al., 2006).

ACE2 expression in the kidney has been studied in both T1DM and T2DM models. In 8-week-old db/db mice, a model of early T2DM, ACE2 expression is elevated while ACE expression is decreased in both glomeruli and cortex (Ye et al., 2004) prior to the development of diabetic nephropathy. Similarly, in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice, a T1DM model, ACE2 protein expression is elevated in the early (Wysocki et al., 2006) and decreased in the late (Tikellis et al., 2003) phase of diabetic nephropathy. Additionally, in humans, ACE expression is increased while ACE2 expression is decreased in the tubules in diabetic nephropathy (Mizuiri et al., 2008). Decreased ACE2 expression was associated with increased albuminuria (Tikellis et al., 2003) and pharmacological inhibition of ACE2 by MLN-4760 increased urinary albumin excretion 3–4-fold in both T1DM and T2DM models (Soler et al., 2007, Ye et al., 2006). MLN-4760 treatment exacerbated mesangial matrix expansion, vascular thickness (Soler et al., 2007) and also caused focal loss of podocytes in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice, indicating that ACE2 may be required for podocyte maintenance. Finally in two models of T1DM (streptozotocin and Akita mouse models), ACE2 gene deletion accelerated the development of diabetic kidney disease (Wong et al., 2007, Tikellis et al., 2008). Akita mice are a genetic model of T1DM with reduced β-cell activity but without evidence of insulitis (Yoshioka et al., 1997). Interestingly, ACE2 gene deletion in a Akita mouse background, by crossing Akita with ACE2 knockout (ACE2−/y) mice, resulted in increased albuminuria as well as fibronectin and smooth muscle actin expression compared to diabetic mice with intact ACE2 (Wong et al., 2007). On the other hand, in streptozotocin-induced diabetic ACE2−/y mice, ACE2 gene deletion inhibited the beneficial effects of ACE inhibitor (Tikellis et al., 2008) in diabetic nephropathy, suggesting that ACE inhibition potentiates ACE2 activity. ARB therapy did however reduce albuminuria in Akita-ACE2−/y mice (Wong et al., 2007). Interestingly, Ang-(1–7) administration also worsened diabetic kidney injury in streptozotocin-induced diabetes, indicating that the effects of ACE2 may be mediated by the loss of Ang-II rather than via Ang-(1–7) (Shao et al., 2008). The current findings suggest that ACE2 may participate in a compensatory mechanism in the diabetic kidney prior to the onset of diabetic nephropathy. Indeed, several studies demonstrated that loss or inhibition of ACE2 exacerbates diabetic nephropathy (Ye et al., 2006, Soler et al., 2007, Wong et al., 2007, Tikellis et al., 2008). Moreover, the localization of ACE2 in the podocytes early in the development of diabetes indicates that it may protect against podocyte loss, thus preventing the worsening glomerular injury (Yu et al., 2005) and confirming ACE2 as an important target for future studies of diabetic kidney disease.

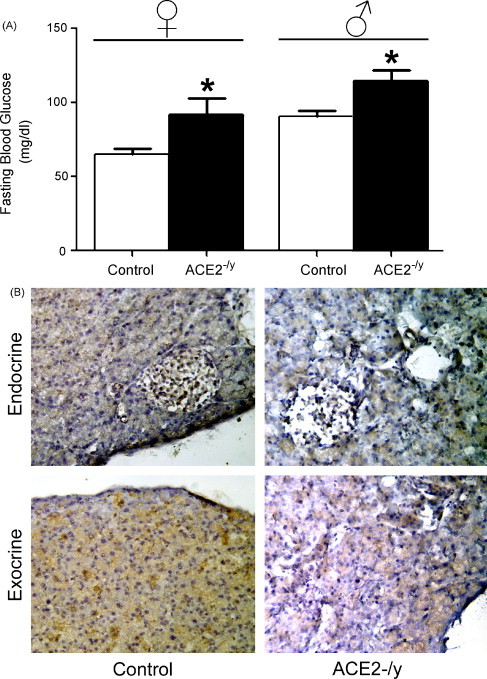

6. ACE2 in the endocrine pancreas

Expression of both ACE2 (Tikellis et al., 2004b) and Ang-(1–7) (Chappell et al., 1991) has been identified in the rat and canine endocrine pancreas. In diabetic Zucker fatty rats, a genetic model of T2DM characterized by obesity, hyperglycemia, reduced insulin sensitivity and secretion (Clark et al., 1983), ACE2 protein and mRNA expression are elevated in both acini and islets and correlated to an increase in ACE, collagen IV and TGF-β1 levels (Tikellis et al., 2004b). Although ACE2−/y mice are not diabetic, we observed a significant increase in fasting blood glucose in both males (90 ± 4 vs. 115 ± 7; P < 0.05) and females (65 ± 4 vs. 92 ± 10; P < 0.05) ACE2−/y mice compared to littermates (Fig. 2A). However, there was no significant difference in body weight in comparison to littermates (23.3 ± 1.2 vs. 23.1 ± 0.9, P > 0.05). We also observed Mas receptor expression in the pancreas, which was decreased in ACE2−/y mice (Fig. 2B). ACE2 and therefore Ang-(1–7) may potentially influence islet function through modulation of blood flow and inhibition of fibrosis, via modulation of NO release. Islet blood flow is enhanced during increased functional demand due to glucose infusion (Styrud et al., 1992), obesity (Atef et al., 1992), pancreatectomy (Jansson and Sandler, 1981) and diabetes (Carlsson et al., 1996, Carlsson et al., 1997). Notably, enhanced islet perfusion is accompanied by an increase in islet capillary BP in Goto-Kakizaki rat, a model of T2DM (Carlsson et al., 1997). Altered islet blood flow has been associated with abnormal secretion of glucagon (Samols and Stagner, 1988) and insulin (Atef et al., 1994). NO regulates both basal (Carlsson et al., 1996) and glucose-mediated islet blood flow (Moldovan et al., 1996). Elevated ACE2 levels in diabetes may lead to increased Ang-(1–7) levels in the islet, which could result in vasodilation through stimulation of NO release (Portsi et al., 1994, Heitsch et al., 2001). Accordingly, increased Ang-(1–7) stimulation of NO signaling would then be a potential mechanism for increased islet blood flow seen in T1DM and T2DM.

Fig. 2.

Consequences of ACE2 gene deletion. (A) Following a 12-h fast, fasting blood glucose levels were measured in females (n = 5) and males (n = 8) ACE2 knockout mice using an Accu-Check® Aviva glucometer (Roche). ACE2 knockout mice have elevated fasting blood glucose in comparison to age-matched littermates. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05: statistical significance vs. control mice. (B) Mas receptor immunohistochemistry reveals expression of this Ang-(1–7) receptor in the mouse endocrine and exocrine pancreas. Mas receptor expression was reduced in ACE2−/y mice. Pancreas sections (16 μm) were incubated with a rabbit anti-Mas antibody (AbCam) for 18 h at 4 °C and developed using the standard ABC method (Vector Laboratories) using DAB as the chromagen. A brown staining is indicative of Mas receptor immuno-reactivity.

Ang-II is well known for its pro-inflammatory (Suzuki et al., 2003) and pro-fibrotic actions (Mezzano et al., 2001, Weber et al., 1993), while several studies have demonstrated the ability of ACE2 to inhibit these effects in disease states (Diez-Freire et al., 2006, Huentelman et al., 2005, Paizis et al., 2005, Herath et al., 2007). In addition, TGF-β plays an important role in the development of islet dysfunction and loss of islet morphology (Donath et al., 2003), which is one potential cause of pancreatic β-cell failure (Johnson et al., 2003). TGF-β is implicated in the development of fibrosis in many disease states (Branton and Kopp, 1999) and its expression is elevated in the islets of mice with T2DM (Tikellis et al., 2004b, Yamamoto et al., 1993). On the other hand, RAS blockade decreases TGF-β expression in the islet and is associated with improved islet morphology and function (Tikellis et al., 2004b). While the effects of ACE2 on the preservation of islet architecture have not been investigated, combined evidence of the effectiveness of ACE2 at inhibiting fibrosis (Diez-Freire et al., 2006, Huentelman et al., 2005) and the ability of the enzyme to reduce TGF-β expression in models of cardiac fibrosis (Grobe et al., 2007) suggest that ACE2-mediated inhibition of TGF-β expression may prevent islet fibrosis and loss of islet function.

7. Potential role for ACE2 in insulin resistance

While there have been no studies on the effect of ACE2 or Ang-(1–7) on glucose metabolism in the liver, ACE2 has been identified in hepatocytes (Paizis et al., 2005). Along with other RAS components, ACE2 is elevated in hepatic fibrogenic diseases (Paizis et al., 2005, Herath et al., 2007). Mas receptor expression has also been identified in the liver and is elevated in biliary fibrosis (Herath et al., 2007). ACE2 expression is also elevated in hypoxic conditions in the liver (Paizis et al., 2005), supporting a potential compensatory role for the carboxypeptidase.

Although ACE2 mRNA has also been identified in white adipose tissue (Galvez-Prieto et al., 2008, Gembardt et al., 2005), the physiological implications of this observation have not been studied. Santos et al. however, recently reported the effects of Mas receptor deficiency on metabolism (Santos et al., 2007). Ang-(1–7) binding to the G-protein-coupled Mas receptor (Santos et al., 2003) has been shown to inhibit Ang-II responses (da Costa Goncalves et al., 2007, Tallant et al., 2005, Sampaio et al., 2007). Mas knockout (Mas−/−) mice exhibit many common features of metabolic syndrome (Santos et al., 2007), an aforementioned risk factor for T2DM. While there was no difference in body weight or food intake, Mas−/− mice have elevated leptin and insulin levels and increased epididymal and retroperitoneal fat mass. Additionally, these mice are dyslipidemic, exhibiting elevated serum and muscle triglycerides and blood cholesterol levels. Mas−/− mice also exhibit impaired insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance, reduced adipose glucose uptake and impaired glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) expression (Santos et al., 2007). This study clearly demonstrates that loss of the Mas receptor leads to metabolic dysfunction and implicates the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas receptor axis in the development of insulin resistance.

Obesity and insulin resistance are associated with impaired endothelium-dependent and insulin-mediated vasodilation (Laakso et al., 1990, Steinberg et al., 1996, Williams et al., 1996). Moreover, obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes are associated with decreased exercise-induced hyperemia (Fossum et al., 1998, Frisbee, 2006, Xiang et al., 2008), and exercise-induced muscle glucose uptake (Laine et al., 1998, Utriainen et al., 1998, Peltoniemi et al., 2001). In both T1DM and T2DM, glucose transport from the blood to the skeletal muscle has been shown to be the major impediment to skeletal muscle glucose uptake (Fueger et al., 2004, Baron et al., 1991). It is well known that Ang-(1–7) potentiates bradykinin-mediated vasodilation (Paula et al., 1995, Lima et al., 1997). In both T1DM and T2DM, loss of Ang-(1–7) potentiation of bradykinin-mediated vasodilation is rescued by chronic but not acute insulin (Oliveira et al., 2002, Rastelli et al., 2007). While Oliviera et al. demonstrated that Ang-(1–7) potentiation of bradykinin was not dependent on NO but instead on voltage gated K+ channels (Oliveira et al., 2002), Rastelli et al. showed that NO, K+ channels and prostanoids influenced this pathway (Rastelli et al., 2007).

In addition to modulation of vasodilation, bradykinin signaling increases GLUT4 translocation (Kishi et al., 1998) and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue (Beard et al., 2006, Kishi et al., 1998). Moreover, bradykinin-mediated enhancement of glucose uptake in the adipose tissue has been shown to involve NO (Beard et al., 2006). Indeed, ACE inhibitors improve skeletal muscle glucose uptake through a bradykinin-mediated increase in NO (Henriksen et al., 1999). Ang-(1–7)-mediated potentiation of bradykinin signaling may then also affect GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake by the skeletal muscle. Blunting of this pathway may thus exacerbate the development of insulin resistance and diabetes.

8. Summary

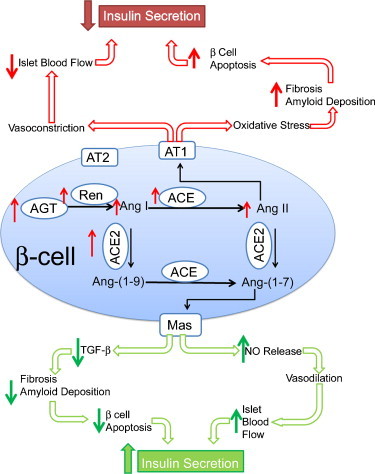

Hyperactivity of the RAS is involved in the pathogenesis of diabetes and diabetic complications. ACE2, a new component of the RAS, is elevated in diabetes and diabetic nephropathy and may be involved in a compensatory mechanism opposing the ACE/Ang-II/AT1-receptor axis. In the islets, ACE2 may modulate blood flow and morphology in order to maintain insulin secretion (Fig. 3 ). This compensatory effect of ACE2 in diabetes has already been suggested in the kidney by studies demonstrating that ACE2 inhibition worsens diabetic nephropathy. In addition, Ang-(1–7), the product of Ang-II cleavage by ACE2, mediates vasodilation and therefore may enhance insulin sensitivity. In conclusion, recent data from the literature and our laboratory suggest that ACE2 expression is modulated during diabetes and that ACE2 deletion affects glucose homeostasis.

Fig. 3.

Hypothetical model for the role of ACE2 in the pancreas. Ang-II is known to decrease islet blood flow and increase islet oxidative stress, which can cause β-cell apoptosis and decrease insulin secretion. The red arrows emphasize hyperglycemia-induced changes in the islet RAS and its consequences. ACE2 through TGF-β inhibition may reduce amyloid deposition, islet fibrosis and subsequent β-cell apoptosis. Ang-(1–7)-mediated vasodilation may lead to increased blood flow. The combined reduction in β-cell apoptosis and increase in islet blood flow could cause an increase in insulin secretion and preservation of islet function in diabetes. The green arrows highlight hypothetical pathways by which ACE2 may influence islet function.

9. Perspectives

Several transgenic models are already in the pipeline to further address the role of ACE2 in diabetes and metabolic diseases and future studies are likely to confirm ACE2 as a new target for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and its complications. Animal models lacking ACE2 can be useful to demonstrate the role of ACE2 in the development of diabetes and diabetic complications. Accordingly, the breeding of ACE2−/y with Akita mice has already revealed the importance of ACE2 in the prevention of diabetic kidney disease (Wong et al., 2007). Similar strategies involving ACE2 knockout mice and other diabetic models could further our understanding of the role of ACE2 in the development of diabetes and other diabetic complications. Additionally, DX600 (Huang et al., 2003) and MLN-4760 (Tikellis et al., 2003), two inhibitors of ACE2, have both been shown to be effective at reducing the effects of the enzyme. These compounds could be delivered to animals prior to or after the onset of diabetes to demonstrate the influence of ACE2 or Ang-(1–7) on the development of diabetes or diabetic complications.

Enhancing ACE2 through pharmacological or genetic intervention is also an attractive option for the prevention and treatment of diabetes and diabetic complications. Ferreira et al., recently demonstrated the efficacy of 2 pharmacological activators of ACE2, among which 1-[[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]amino]-4-(hydroxymethyl)-7-[[(4-methylphenyl)sulfonyl]oxy]-9H-xanthen-9-one (XNT) is capable of reducing cardiac fibrosis and high blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats (Ferreira and Raizada, 2008). Finally, ACE2 viral delivery, and therefore over-expression, has been shown to reduce Ang-II-mediated responses (Feng et al., 2008, Huentelman et al., 2005).

In addition to the modulation of ACE2, direct targeting of Ang-(1–7) is also possible. To this end, the Ang-(1–7) receptor antagonist, D-Ala7-Ang-(1–7) (Santos et al., 1994), and the Ang-(1–7) analogue, AVE 0991 (Wiemer et al., 2002), are available. Recently, Shao et al. demonstrated that Ang-(1–7) infusion worsens diabetic kidney disease, which seems to oppose the idea that ACE2 is beneficial in diabetic kidney disease (Shao et al., 2008). These findings highlight the need for further study of the Ang-(1–7) signaling pathways and other potential effects of ACE2. The combination of the different strategies could help to discriminate between the effects of Ang-(1–7) generation and ACE2 activation in the development of diabetes and clarify the role of the ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/Mas receptor axis in this fast-progressing disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. Thomas M. Coffman, Susan B. Gurley (Duke University) and Ore Pharmaceuticals Inc. for providing the ACE2 knockout mice. This work was supported, in part, by NIH grants NS052479 and P20 RR018766.

References

- Abuissa H., Jones P.G., Marso S.P., O’Keefe J.J.H. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers for prevention of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005;46:821–826. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida A.P., Frábregas B.C., Madureira M.M., Santos R.J.S., Campagnole-Santos M.J., Santos R.A.S. Angiotensin-(1–7) potentiates the coronary vasodilatatory effect of bradykinin in the isolated rat heart. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2000;33:709–713. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2000000600012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous Efficacy of atenolol and captopril in reducing risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 39. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. BMJ. 1998;317:713–720. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Lancet. 2000;355:253–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous Type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents. American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1442–1443. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atef N., Ktorza A., Picon L., Penicaud L. Increased islet blood flow in obese rats: role of the autonomic nervous system. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 1992;262:E736–740. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.262.5.E736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atef N., Portha B., Pénicaud L. Changes in islet blood flow in rats with NIDDM. Diabetologia. 1994;37:677–680. doi: 10.1007/BF00417691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader M., Peters J., Baltatu O., Müller D.N., Luft F.C. Tissue renin–angiotensin systems: new insights from experimental animal models in hypertension research. J. Mol. Med. 2001;79:76–102. doi: 10.1007/s001090100210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltatu O., Silva J.A., Jr., Ganten D., Bader M. The brain renin–angiotensin system modulates angiotensin II-induced hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2000;35(1 Pt 2):409–412. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron A.D., Laakso M., Brechtel G., Edelman S.V. Mechanism of insulin resistance in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a major role for reduced skeletal muscle blood flow. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1991;73:637–643. doi: 10.1210/jcem-73-3-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bataller R., Sancho-bru P., Ginès P., Lora J.M., Al-garawi A., Solé M., Colmenero J., Nicolás J.M., Jiménez W., Weich N., Gutiérrez-ramos J.-c., Arroyo V., Rodés J. Activated human hepatic stellate cells express the renin–angiotensin system and synthesize angiotensin II. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00695-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard K.M., Lu H., Ho K., Fantus I.G. Bradykinin augments insulin-stimulated glucose transport in rat adipocytes via endothelial nitric oxide synthase-mediated inhibition of Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Diabetes. 2006;55:2678–2687. doi: 10.2337/db05-1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindokas V.P., Kuznetsov A., Sreenan S., Polonsky K.S., Roe M.W., Philipson L.H. Visualizing superoxide production in normal and diabetic rat islets of Langerhans. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:9796–9801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206913200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branton M.H., Kopp J.B. TGF-beta and fibrosis. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1349–1365. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnihan K.B., Li P., Ferrario C.M. Angiotensin-(1–7) dilates canine coronary arteries through kinins and nitric oxide. Hypertension. 1996;27:523–528. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson P.-O. The renin–angiotensin system in the endocrine pancreas. JOP. 2001;2:26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson P.O., Andersson A., Jansson L. Pancreatic islet blood flow in normal and obese-hyperglycemic (ob/ob) mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 1996;271:E990–E995. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.6.E990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson P.O., Berne C., Jansson L. Angiotensin II and the endocrine pancreas: effects on islet blood flow and insulin secretion in rats. Diabetologia. 1998;41:127–133. doi: 10.1007/s001250050880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson P.O., Jansson L., Ostenson C.G., Kallskog O. Islet capillary blood pressure increase mediated by hyperglycemia in NIDDM GK rats. Diabetes. 1997;46:947–952. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.6.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell M., Millsted A., Diz D., Brosnihan K., Ferrario C.M. Evidence for an intrinsic angiotensin system in the canine pancreas. J. Hypertens. 1991;9:751–759. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199108000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A., Nilsson M.R. Islet amyloid: a complication of islet dysfunction or an aetiological factor in Type 2 diabetes? Diabetologia. 2004;47:157–169. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J., Palmer C., Shaw W. The diabetic Zucker fatty rat. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1983;17:68–75. doi: 10.3181/00379727-173-41611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry D., Bennett L., Grodsky G.M. Dynamics of insulin secretion by the perfused rat pancreas. Endocrinology. 1968;83:572–584. doi: 10.1210/endo-83-3-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa Goncalves A.C., Leite R., Fraga-Silva R.A., Pinheiro S.V., Reis A.B., Reis F.M., Touyz R.M., Webb R.C., Alenina N., Bader M., Santos R.A.S. Evidence that the vasodilator angiotensin-(1–7)-Mas axis plays an important role in erectile function. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;293:H2588–2596. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00173.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabelea D., Hanson R.L., Bennett P.H., Roumain J., Knowler W.C., Pettitt D.J. Increasing prevalence of Type II diabetes in American Indian children. Diabetologia. 1998;41:904–910. doi: 10.1007/s001250051006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabelea D., Pettitt D.J., Jones K.L., Arslanian S.A. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in minority children and adolescents. An emerging problem. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 1999;28:709–729. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Vestra M., Masiero A., Roiter A.M., Saller A., Crepaldi G., Fioretto P. Is podocyte injury relevant in diabetic nephropathy? Studies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:1031–1035. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilczyk U., Sarao R., Remy C., Benabbas C., Stange G., Richter A., Arya S., Pospisilik J.A., Singer D., Camargo S.M.R., Makrides V., Ramadan T., Verrey F., Wagner C.A., Penninger J.M. Essential role for collectrin in renal amino acid transport. Nature. 2006;444:1088–1091. doi: 10.1038/nature05475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danser A.H.J., Schalekamp M.A.D.H. Is there an internal cardiac renin–angiotensin system? Heart. 1996;76:28–32. doi: 10.1136/hrt.76.3_suppl_3.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cavanagh E.M.V., Inserra F., Toblli J., Stella I., Fraga C.G., Ferder L. Enalapril attenuates oxidative stress in diabetic rats. Hypertension. 2001;38:1130–1136. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.092845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Freire C., Vazquez J., Correa de Adjounian M.F., Ferrari M.F.R., Yuan L., Silver X., Torres R., Raizada M.K. ACE2 gene transfer attenuates hypertension-linked pathophysiological changes in the SHR. Physiol. Genomics. 2006;27:12–19. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00312.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath M.Y., Størling J., Maedler K., Mandrup-Poulsen T. Inflammatory mediators and islet ß-cell failure: a link between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. J. Mol. Med. 2003;81:455–470. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0450-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue M., Hsieh F., Baronas E., Godbout K., Gosselin M., Stagliano N., Donovan M., Woolf B., Robison K., Jeyaseelan R., Breitbart R.E., Acton S. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1–9. Circ. Res. 2000;87:E1–E9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.5.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake A.J., Smith A., Betts P.R., Crowne E.C., Shield J.P.H. Type 2 diabetes in obese white children. Arch. Dis. Child. 2002;86:207–208. doi: 10.1136/adc.86.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzau V.J., Re R. Tissue angiotensin system in cardiovascular medicine. A paradigm shift? Circulation. 1994;89:493–498. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehtisham S., Barrett T.G., Shaw N.J. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in UK children—an emerging problem. Diabet. Med. 2000;17:867–871. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J.L., Goldfine I.D., Maddux B.A., Grodsky G.M. Oxidative stress and stress-activated signaling pathways: a unifying hypothesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr. Rev. 2002;23:599–622. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Yue X., Xia H., Bindom S.M., Hickman P., Filipeanu C., Wu G., Lazartigues E. ACE2 over-expression in the subfornical organ prevents the angiotensin-II-mediated pressor and drinking responses and is associated with AT1 receptor down-regulation. Circ. Res. 2008;102:628–629. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.169110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes L., Fortes Z.B., Nigro D., Tostes R.C.A., Santos R.A.S., Catelli de Carvalho M.H. Potentiation of bradykinin by angiotensin-(1–7) on arterioles of spontaneously hypertensive rats studied in vivo. Hypertension. 2001;37:703–709. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A.J., Raizada M.K. Genomic and proteomic approaches for targeting angiotensin converting enzyme2 for cardiovascular diseases. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2008;23:364–369. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328303b79b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliser D., Schaefer F., Schmid D., Veldhuis J.D., Ritz E. Angiotensin II affects basal, pulsatile, and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in humans. Hypertension. 1997;30:1156–1161. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.5.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossum E., Hoieggen A., Moan A., Rostrup M., Nordby G., Kjeldsen S.E. Relationship between insulin sensitivity and maximal forearm blood flow in young men. Hypertension. 1998;32:838–843. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.5.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisbee J.C. Vascular adrenergic tone and structural narrowing constrain reactive hyperemia in skeletal muscle of obese Zucker rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006;290:H2066–H2074. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01251.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fueger P.T., Bracy D.P., Malabanan C.M., Pencek R.R., Wasserman D.H. Distributed control of glucose uptake by working muscles of conscious mice: roles of transport and phosphorylation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;286:E77–E84. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00309.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher P.E., Chappell M.C., Bernish B.W., Tallant E.A. Abstract Presented at the 57th Annual Fall Conference and Scientific sessions of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. 2003. ACE2 expression in brain: angiotensin II down-regulates ACE2 in astrocytes. [Google Scholar]

- Galvez-Prieto B., Bolbrinker J., Stucchi P., de las Heras A.I., Merino B., Arribas S., Ruiz-Gayo M., Huber M., Wehland M., Kreutz R., Fernandez-Alfonso M.S. Comparative expression analysis of the renin–angiotensin system components between white and brown perivascular adipose tissue. J. Endocrinol. 2008;197:55–64. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gembardt F., Sterner-Kock A., Imboden H., Spalteholz M., Reibitz F., Schultheiss H.-P., Siems W.-E., Walther T. Organ-specific distribution of ACE2 mRNA and correlating peptidase activity in rodents. Peptides. 2005;26:1270–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerich J.E. Is reduced first-phase insulin release the earliest detectable abnormality in individuals destined to develop type 2 diabetes? Diabetes. 2002;51:S117–S121. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gironacci M.M., Valera M.S., Yujnovsky I., Pena C. Angiotensin-(1–7) inhibitory mechanism of norepinephrine release in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2004;44:783–787. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000143850.73831.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grankvist K., Marklund S., Taljedal I. CuZn-superoxide dismutase, Mn-superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase in pancreatic islets and other tissues in the mouse. Biochem. J. 1981;199:393–398. doi: 10.1042/bj1990393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gress T.W., Nieto F.J., Shahar E., Wofford M.R., Brancati F.L. Hypertension and antihypertensive therapy as risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;342:905–912. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griendling K.K., Minieri C.A., Ollerenshaw J.D., Alexander R.W. Angiotensin II stimulates NADH and NADPH oxidase activity in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 1994;74:1141–1148. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.6.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobe J.L., Der sarkissian S., Stewart J.M., Meszaros J.G., Raizada M.K., Katovich M.J. ACE2 overexpression inhibits hypoxia-induced collagen production by cardiac fibroblasts. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2007;113:357–364. doi: 10.1042/CS20070160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy S.M., Benjamin I.J., Burke G.L., Chait A., Eckel R.H., Howard B.V., Mitch W., Smith S.C., Jr., Sowers J.R. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 1999;100:1134–1146. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley S.B., Allred A., Le T.H., Griffiths R., Mao L., Philip N., Haystead T.A., Donoghue M., Breitbart R.E., Acton S.L., Rockman H.A., Coffman T.M. Altered blood pressure responses and normal cardiac phenotype in ACE2-null mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2218–2225. doi: 10.1172/JCI16980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy J.L., Jackson R.M., Acharya K.R., Sturrock E.D., Hooper N.M., Turner A.J. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2): comparative modeling of the active site, specificity requirements, and chloride dependence. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13185–13192. doi: 10.1021/bi035268s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon J.S., Stein R., Robertson R.P. Oxidative stress-mediated, post-translational loss of MafA protein as a contributing mechanism to loss of insulin gene expression in glucotoxic beta cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:11107–11113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410345200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison D.G., Gongora M.C., Guzik T.J., Widder J. Oxidative stress and hypertension. JASH. 2007;1:30–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden M., Karuparthi P., Habibi J., Waseker C., Lastra G., Marnrique C., Stas S., Sowers J. Ultrastructural islet study of early fibrosis in the Ren2 model of hypertension. Emerging role of the islet pancreatic pericyte-stellate cell. JOP. 2007;8:725–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden M., Tyagi S. Islet redox stress: the manifold toxicities of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and amylin derived islet amyloid in type 2 diabetes mellitus. JOP. 2002;3:86–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitsch H., Brovkovych S., Malinski T., Wiemer G. Angiotensin-(1–7)-stimulated nitric oxide and superoxide release from endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2001;37:72–76. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen E.J., Jacob S., Kinnick T.R., Youngblood E.B., Schmit M.B., Dietze G.J. ACE inhibition and glucose transport in insulinresistant muscle: roles of bradykinin and nitric oxide. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1999;277:R332–R336. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.1.R332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herath C., Warner F.J., Lubel J., Dean R.J., Jia Z., Lew R.A., Smith A.I., Burrell L.M., Angus P.W. Upregulation of hepatic angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and angiotensin-(1–7) levels in experimental billiary fibrosis. J. Hepatol. 2007;47:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Sexton D.J., Skogerson K., Devlin M., Smith R., Sanyal I., Parry T., Kent R., Enright J., Wu Q.L., Conley G., DeOliveira D., Morganelli L., Ducar M., Wescott C.R., Ladner R.C. Novel peptide inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15532–15540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huentelman M.J., Grobe J.L., Vazquez J., Stewart J.M., Mecca A.P., Katovich M.J., Ferrario C.M., Raizada M.K. Protection from angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis by systemic lentiviral delivery of ACE2 in rats. Exp. Physiol. 2005;90:783–790. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.031096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y., Kuba K., Penninger J.M. The discovery of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and its role in acute lung injury in mice. Exp. Physiol. 2008;93:543–548. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y., Kuba K., Rao S., Huan Y., Guo F., Guan B., Yang P., Sarao R., Wada T., Leong-Poi H., Crackower M.A., Fukamizu A., Hui C.-C., Hein L., Uhlig S., Slutsky A.S., Jiang C., Penninger J.M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson L., Sandler S. Pancreatic and islet blood flow in the regenerating pancreas after a partial pancreatectomy in adult rats. Surgery. 1981;106:861–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J.D., Ahmed N.T., Luciani D.S., Han Z., Tran H., Fujita J., Misler S., Edlund H., Polonsky K.S. Increased islet apoptosis in Pdx1 ± mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1147–1160. doi: 10.1172/JCI16537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneto H., Xu G., Song K.-H., Suzuma K., Bonner-Weir S., Sharma A., Weir G.C. Activation of the hexosamine pathway leads to deterioration of pancreatic beta-cell function through the induction of oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:31099–31104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104115200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King H., Aubert R.E., Herman W.H. Global burden of diabetes, 1995–2025: prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1414–1431. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi K., Muromoto N., Nakaya Y., Miyata I., Hagi A., Hayashi H., Ebina Y. Bradykinin directly triggers GLUT4 translocation via an insulin-independent pathway. Diabetes. 1998;47:550–558. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.4.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konoshita T., Wakahara S., Mizuno S., Motomura M., Aoyama C., Makino Y., Kawai Y., Kato N., Koni I., Miyamori I., Mabuchi H. Tissue gene expression of renin–angiotensin system in human type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2006;4:848–852. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laakso M., Edelman S.V., Brechtel G., Baron A.D. Decreased effect of insulin to stimulate skeletal muscle blood flow in obese man. A novel mechanism for insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;85:1844–1852. doi: 10.1172/JCI114644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine H., Yki-Jarvinen H., Kirvela O., Tolvanen T., Raitakari M., Solin O., Haaparanta M., Knuuti J., Nuutila P. Insulin resistance of glucose uptake in skeletal muscle cannot be ameliorated by enhancing endothelium-dependent blood flow in obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:1156–1162. doi: 10.1172/JCI1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert D.W., Yarski M., Warner F.J., Thornhill P., Parkin E.T., Smith A.I., Hooper N.M., Turner A.J. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha convertase (ADAM17) mediates regulated ectodomain shedding of the severe-acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30113–30119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505111200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langheinrich M., Ae Lee M., Böhm M., Pinto Y.M., Ganten D., Paul M. The hypertensive Ren-2 transgenic rat TGR (mREN2)27 in hypertension research. Characteristics and functional aspects. Am. J. Hypertens. 1996;9:506–512. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)00400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau T., Carlsson P.O., Leung P.S. Evidence for a local angiotensin-generating system and dose-dependent inhibition of glucose-stimulated insulin release by angiotensin II in isolated pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2004;47:240–248. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie J.L., Sigmund C.D. Minireview: overview of the renin–angiotensin system—an endocrine and paracrine system. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2179–2183. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung P., Chan H., Wong P. Immunohistochemical localization of angiotensin II in the mouse pancreas. Histochem. J. 1998;30:21–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1003210428276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung P.S. The physiology of a local renin–angiotensin system in the pancreas. J. Physiol. 2007;580:31–37. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung P.S., Chan W.P., Wong T.P., Sernia C. Expression and localization of the renin–angiotensin system in the rat pancreas. J. Endocrinol. 1999;160:13–19. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1600013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Sui J., Wong S.K., Berne M.A., Somasundaran M., Sullivan J.L., Luzuriaga K., Greenough T.C., Choe H., Farzan M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima C.V., Paula R.D., Resende F.L., Khosla M.C., Santos R.A.S. Potentiation of the hypotensive effect of bradykinin by short-term infusion of angiotensin-(1–7) in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1997;30:542–548. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.3.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupi R., Guerra S.D., Bugliani M., Boggi U., Mosca F., Torri S., Prato S.D., Marchetti P. The direct effects of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, zofenoprilat and enalaprilat, on isolated human pancreatic islets. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2006;154:355–361. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maechler P., Jornot L., Wollheim C.B. Hydrogen peroxide alters mitochondrial activation and insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:27905–27913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason J.M., Dickenson H.O., Nicholson D.J., Campbel F., Ford G., Williams B. The diabetogenic potential of thiazide-type and beta blocker combinations in patients with hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2005;23:1777–1781. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000177537.91527.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka T.-A., Kajimoto Y., Watada H., Kaneto H., Kishimoto M., Umayahara Y., Fujitani Y., Kamada T., Kawamori R., Yamasaki Y. Glycation-dependent, reactive oxygen species-mediated suppression of the insulin gene promoter activity in HIT cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:144–150. doi: 10.1172/JCI119126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T.W., Bennett P.H., Nelson R.G. Podocyte number predicts long-term urinary albumin excretion in Pima Indians with Type II diabetes and microalbuminuria. Diabetologia. 1999;42:1341–1344. doi: 10.1007/s001250051447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzano S.A., Ruiz-Ortega M., Egido J. Angiotensin II and renal fibrosis. Hypertension. 2001;38:635–638. doi: 10.1161/hy09t1.094234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuiri S., Hemmi H., Arita M., Ohashi Y., Tanaka Y., Miyagi M., Sakai K., Ishikawa Y., Shibuya K., Hase H., Aikawa A. Expression of ACE and ACE2 in individuals with diabetic kidney disease and healthy controls. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2008;51:613–623. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan S., Livingston E., Zhang R.S., Kleinman R., Girth P., Brunicardi F.C. Glucose-induced islet hyperemia is mediated by nitric oxide. Am. J. Surg. 1996;171:16–20. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama M., Inoguchi T., Sonta T., Maeda Y., Sasaki S., Sawada F., Tsubouchi H., Sonoda N., Kobayashi K., Sumimoto H., Nawata H. Increased expression of NAD(P)H oxidase in islets of animal models of Type 2 diabetes and its improvement by an AT1 receptor antagonist. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;332:927–933. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld N.D., Raffel L.J., Landon C., Chen Y.D., Vadheim C.M. Early presentation of type 2 diabetes in Mexican–American youth. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:80–86. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niklason A., Hedner T., Kiskanen L., Lanke J. Development of diabetes is retarded by ACE inhibition in hypertensive patients: a sub-analysis of the Captopril Prevention Project. J. Hypertens. 2004;38:E28–E32. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200403000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira H.R., Verlengia R., Carvalho C.R.O., Britto L.R.G., Curi R., Carpinelli A.R. Pancreatic beta-cells express phagocyte-like NAD(P)H oxidase. Diabetes. 2003;52:1457–1463. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.6.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira M.A., Bruno Fortes Z.B., Santos R.A., Kosla M.C., De Carvalho M.H. Synergistic effect of angiotensin-(1–7) on bradykinin arteriolar dilation in vivo. Peptides. 1999;20:1195–1201. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(99)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira M.A., Carvalho M.H.C., Nigro D., Passaglia R.d.C.A.T., Fortes Z.B. Angiotensin-(1–7) and bradykinin interaction in diabetes mellitus: in vivo study. Peptides. 2002;23:1449–1455. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagtalunan M., Miller P., Jumping-Eagle S., Nelson R., Myers R., Rennke H., Coplon N., Sun L., Meyer T. Podocyte loss and progressive glomerular injury in type II diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:342–348. doi: 10.1172/JCI119163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paizis G., Cooper M.E., Schembri J.M., Tikellis C., Burrell L.M., Angus P.W. Up-regulation of components of the renin–angiotensin system in the bile duct-ligated rat liver. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1667–1676. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paizis G., Tikellis C., Cooper M.E., Schembri J.M., Lew R.A., Smith A.I., Shaw T., Warner F.J., Zuilli A., Burrell L.M., Angus P.W. Chronic liver injury in rats and humans upregulates the novel enzyme angiotensin converting enzyme 2. Gut. 2005;54:1790–1796. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.062398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M., Poyan Mehr A., Kreutz R. Physiology of local renin–angiotensin systems. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:747–803. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paula R.D., Lima C.V., Khosla M.C., Santos R.A.S. Angiotensin-(1–7) potentiates the hypotensive effect of bradykinin in conscious rats. Hypertension. 1995;26:1154–1159. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.6.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltoniemi P., Yki-Jarvinen H., Oikonen V., Oksanen A., Takala T.O., Ronnemaa T., Erkinjuntti M., Knuuti M.J., Nuutila P. Resistance to exercise-induced increase in glucose uptake during hyperinsulinemia in insulin-resistant skeletal muscle of patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2001;50:1371–1377. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinhas-Hamiel O., Zeitler P. The global spread of type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2005;146:693–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portsi I., Bara A., Busse R., Hecker M. Release of nitric oxide by angiotensin-(1–7) from porcine coronary endothelium: implications for a novel angiotensin receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;111:652–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb14787.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastelli V.M.F., Oliveira M.A., dos Santos R., de Cássia Tostes Passaglia R., Nigro D., de Carvalho M.H.C., Fortes Z.B. Lack of potentiation of bradykinin by angiotensin-(1–7) in a type 2 diabetes model: role of insulin. Peptides. 2007;28:1040–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid C.M., Johnston C.I., Ryan P., Willson K., Wing L.M. Diabetes and cardiovascular outcomes in elderly subjects treated with ace-inhibitors or diuretics: findings from the 2ND Australian national blood pressure study. Am. J. Hypertens. 2003;16:A11. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson R.P. Chronic oxidative stress as a central mechanism for glucose toxicity in pancreatic islet beta cells in diabetes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:42351–42354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samols E., Stagner J. Intra-islet regulation. Am. J. Med. 1988;85:31–35. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio W.O., Souza dos Santos R.A., Faria-Silva R., da Mata Machado L.T., Schiffrin E.L., Touyz R.M. Angiotensin-(1–7) through receptor Mas mediates endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation via Akt-dependent pathways. Hypertension. 2007;49:185–192. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000251865.35728.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos R.A., Campagnole-Santos M.J., Baracho N.C., Fontes M.A., Silva L.C., Neves L.A., Oliveira D.R., Caligiorne S.M., Rodrigues A.R., Gropen Júnior C. Characterization of a new angiotensin antagonist selective for angiotensin-(1–7): evidence that the actions of angiotensin-(1–7) are mediated by specific angiotensin receptors. Brain Res. Bull. 1994;35:293–298. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos R.A.S., e Silva A.C.S., Maric C., Silva D.M.R., Machado R.P., de Buhr I., Heringer-Walther S., Pinheiro S.V.B., Lopes M.T., Bader M., Mendes E.P., Lemos V.S., Campagnole-Santos M.J., Schultheiss H.-P., Speth R., Walther T. Angiotensin-(1–7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:8258–8263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432869100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos S.H.S., Fernandes L.R., Mario E.G., Ferreira A.V.M., Porto L.C.J., Alvarez-Leite J.I., Botion L.M., Bader M., Alenina N., Santos R.A.S. Mas deficiency in FVB/N mice produces marked changes in lipid and glycemic metabolism. Diabetes. 2007;57:340–347. doi: 10.2337/db07-0953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid H., Henger A., Cohen C.D., Frach K., Grone H.-J., Schlondorff D., Kretzler M. Gene expression profiles of podocyte-associated molecules as diagnostic markers in acquired proteinuric diseases. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003;14:2958–2966. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000090745.85482.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J., Iwashita N., Ikeda F., Ogihara T., Uchida T., Shimizu T., Uchino H., Hirose T., Kawamori R., Watada H. Beneficial effects of candesartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, on [beta]-cell function and morphology in db/db mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;344:1224–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y., He M., Zhou L., Yao T., Huang Y., Lu L.M. Chronic angiotensin (1–7) injection accelerates STZ-induced diabetic renal injury. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2008;29:829–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler M.J., Wysocki J., Ye M., Lloveras J., Kanwar Y., Batlle D. ACE2 inhibition worsens glomerular injury in association with increased ACE expression in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Kidney Int. 2007;72:614–623. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg H., Chaker H., Leaming R., Johnson A., Brechtel G., Baron A.D. Obesity/insulin resistance is associated with endothelial dysfunction. Implications for the syndrome of insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:2601–2610. doi: 10.1172/JCI118709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styrud J., Eriksson U.J., Jansson L. A continuous 48-hour glucose infusion in rats causes both an acute and a persistent redistribution of the blood flow within the pancreas. Endocrinology. 1992;130:2692–2696. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.5.1572289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susztak K., Raff A.C., Schiffer M., Bottinger E.P. Glucose-induced reactive oxygen species cause apoptosis of podocytes and podocyte depletion at the onset of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2006;55:225–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y., Ruiz-Ortega M., Lorenzo O., Ruperez M., Esteban V., Egido J. Inflammation and angiotensin II. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2003;35:881–900. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahmasebi M., Puddefoot J.R., Inwang E.R., Vinson G.P. The tissue renin–angiotensin system in human pancreas. J. Endocrinol. 1999;161:317–322. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1610317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallant E.A., Ferrario C.M., Gallagher P.E. Angiotensin-(1–7) inhibits growth of cardiac myocytes through activation of the mas receptor. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;289:H1560–H1566. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00941.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C., Han P., Oprescu A.I., Lee S.C., Gyulkhandanyan A.V., Chan G.N.Y., Wheeler M.B., Giacca A. Evidence for a role of superoxide generation in glucose-induced beta cell dysfunction in vivo. Diabetes. 2007;56:2722–2731. doi: 10.2337/db07-0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikellis C., Bialkowski K., Pete J., Sheehy K., Su Q., Johnston C., Cooper M.E., Thomas M.C. ACE2 deficiency modifies renoprotection afforded by ACE inhibition in experimental diabetes. Diabetes. 2008;57:1018–1025. doi: 10.2337/db07-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikellis C., Cooper M.E., Thomas M.C. Role of the renin–angiotensin system in the endocrine pancreas: implications for the development of diabetes. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2006;38:737–751. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikellis C., Johnston C., Forbes J., Burns W., Thomas M., Lew R., Yarski M., Smith A., Cooper M. Identification of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in the rodent retina. Curr. Eye Res. 2004;29:419–427. doi: 10.1080/02713680490517944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikellis C., Wookey P.J., Candido R., Andrikopoulos S., Thomas M.C., Cooper M.E. Improved islet morphology after blockade of the renin–angiotensin system in the ZDF rat. Diabetes. 2004;53:989–997. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikellis C., Johnston C.I., Forbes J.M., Burns W.C., Burrell L.M., Risvanis J., Cooper M.E. Characterization of renal angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in diabetic nephropathy. Hypertension. 2003;41:392–397. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000060689.38912.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipnis S.R., Hooper N.M., Hyde R., Karran E., Christie G., Turner A.J. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:33238–33243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toblli J.E., Munoz M.C., Cao G., Mella J., Pereyra L., Mastai R. ACE inhibition and AT1 receptor blockade prevent fatty liver and fibrosis in obese zucker rats. Obesity. 2007;16:770–776. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torlone E., Rambotti A.M., Perriello G., Botta G., Santeusanio F., Brunetti P., Bolli G.B. ACE-inhibition increases hepatic and extrahepatic sensitivity to insulin in patients with Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension. Diabetologia. 1991;34:119–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00500383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi H., Inoguchi T., Inuo M., Kakimoto M., Sonta T., Sonoda N., Sasaki S., Kobayashi K., Sumimoto H., Nawata H. Sulfonylurea as well as elevated glucose levels stimulate reactive oxygen species production in the pancreatic [beta]-cell line, MIN6—a role of NAD(P)H oxidase in [beta]-cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;326:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchizono Y., Takeya R., Iwase M., Sasaki N., Oku M., Imoto H., Iida M., Sumimoto H. Expression of isoforms of NADPH oxidase components in rat pancreatic islets. Life Sci. 2006;80:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utriainen T., Takala T., Luotolahti M., Rönnemaa T., Laine H., Ruotsalainen U., Haaparanta M., Nuutila P., Yki-Järvinen H. Insulin resistance characterizes glucose uptake in skeletal muscle but not in the heart in NIDDM. Diabetologia. 1998;41:555–559. doi: 10.1007/s001250050946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdés G., Neves L.A.A., Anton L., Corthorn J., Chacón C., Germain A.M., Merrill D.C., Ferrario C.M., Sarao R., Penninger J., Brosnihan K.B. Distribution of angiotensin-(1–7) and ACE2 in human placentas of normal and pathological pregnancies. Placenta. 2006;27:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermes E., Ducharme A., Bourassa M.G., Lessard M., White M., Tardif J.-C. Enalapril reduces the incidence of diabetes in patients with chronic heart failure: insight from the Studies Of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) Circulation. 2003;107:1291–1296. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000054611.89228.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers C., Hales P., Kaushik V., Dick L., Gavin J., Tang J., Godbout K., Parsons T., Baronas E., Hsieh F., Acton S., Patane M., Nichols A., Tummino P. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:14838–14843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber K., Brilla C., Campbell S., Guarda E., Zhou G., Sriram K. Myocardial fibrosis: role of angiotensin II and aldosterone. Basic Res. Cardiol. 1993;88:107–124. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72497-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemer G., Dobrucki L.W., Louka F.R., Malinski T., Heitsch H. AVE 0991, a nonpeptide mimic of the effects of angiotensin-(1–7) on the endothelium. Hypertension. 2002;40:852–875. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000037979.53963.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S.B., Cusco J.A., Roddy M.A., Johnstone M.T., Creager M.A. Impaired nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1996;27:567–574. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong D.W., Oudit G.Y., Reich H., Kassiri Z., Zhou J., Liu Q.C., Backx P.H., Penninger J.M., Herzenberg A.M., Scholey J.W. Loss of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (Ace2) accelerates diabetic kidney injury. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;171:438–451. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Nicholson W., Knobel S.M., Steffner R.J., May J.M., Piston D.W., Powers A.C. Oxidative stress is a mediator of glucose toxicity in insulin-secreting pancreatic islet cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12126–12134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki J., Ye M., Soler M.J., Gurley S.B., Xiao H.D., Bernstein K.E., Coffman T.M., Chen S., Batlle D. ACE and ACE2 activity in diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2006;55:2132–2139. doi: 10.2337/db06-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang L., Dearman J., Abram S.R., Carter C., Hester R.L. Insulin resistance and impaired functional vasodilation in obese Zucker rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008;294:H1658–H1666. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01206.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K., Ohishi M., Katsuya T., Ito N., Ikushima M., Kaibe M., Tatara Y., Shiota A., Sugano S., Takeda S., Rakugi H., Ogihara T. Deletion of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 accelerates pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction by increasing local angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2006;47:718–726. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000205833.89478.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Nakamura T., Noble N.A., Ruoslahti E., Border W.A. Expression of transforming growth factor beta is elevated in human and experimental diabetic nephropathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:1814–1818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazato M., Yamazato Y., Sun C., Diez-Freire C., Raizada M.K. Overexpression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in the rostral ventrolateral medulla causes long-term decrease in blood pressure in the spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2007;49:926–931. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000259942.38108.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye M., Wysocki J., Naaz P., Salabat M.R., LaPointe M.S., Batlle D. Increased ACE 2 and decreased ACE protein in renal tubules from diabetic mice: a renoprotective combination? Hypertension. 2004;43:1120–1125. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000126192.27644.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye M., Wysocki J., William J., Soler M.J., Cokic I., Batlle D. Glomerular localization and expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin-converting enzyme: implications for albuminuria in diabetes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006;17:3067–3075. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka M., Kayo T., Ikeda T., Koizumi A. A novel locus, Mody4, distal to D7Mit189 on chromosome 7 determines early-onset NIDDM in nonobese C57BL/6 (Akita) mutant mice. Diabetes. 1997;46:887–894. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D., Petermann A., Kunter U., Rong S., Shankland S.J., Floege J. Urinary podocyte loss is a more specific marker of ongoing glomerular damage than proteinuria. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005;16:1733–1741. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005020159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S., Gerstein H., Hoogwerf B., Pogue J., Bosch J., Wolffenbuttel B.H.R., Zinman B., for the H.S.I. Ramipril and the development of diabetes. JAMA. 2001;286:1882–1885. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.15.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Wada J., Hida K., Tsuchiyama Y., Hiragushi K., Shikata K., Wang H., Lin S., Kanwar Y.S., Makino H. Collectrin, a collecting duct-specific transmembrane glycoprotein, is a novel homolog of ACE2 and is developmentally regulated in embryonic kidneys. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:17132–17139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006723200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wada J., Yasuhara A., Iseda I., Eguchi J., Fukui K., Yang Q., Yamagata K., Hiesberger T., Igarashi P., Zhang H., Wang H., Akagi S., Kanwar Y., Makino H. The role for HNF-1β-targeted collectrin in maintenance of primary cilia and cell polarity in collecting duct cells. PLos ONE. 2007;2:e414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zhong J.C., Yu X.Y., Lin Q.X., Li X.H., Huang X.Z., Xiao D.Z., Lin S.G. Enhanced angiotensin converting enzyme 2 regulates the insulin//Akt signalling pathway by blockade of macrophage migration inhibitory factor expression. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]