Abstract

Virus particle formation of HIV-1 is a multi-step process driven by a viral structural protein Gag. This process takes place at the plasma membrane in most cell types. However, the pathway that directs Gag to the plasma membrane has recently come under intense scrutiny because of its importance in production of progeny virions as well as virus transmission at cell-cell contacts. This review highlights recent advances in our current understanding of mechanisms that traffic and localize Gag to the plasma membrane. In addition, findings on Gag association with specific plasma membrane domains are discussed in light of potential roles in cell-to-cell transmission.

Keywords: Plasma membrane, Gag, virus assembly, endosomal trafficking, late endosome/multivesicular body, membrane microdomain, membrane raft, tetraspanin, virological synapse, phosphatidylinositol-(4, 5)-bisphosphate

Introduction

For successful virus spread, the site of virus assembly needs to be precisely regulated. Defects in this process could either inhibit efficient production of infectious virions or block transmission to another host cell, or both. Therefore, mechanisms ensuring proper localization of viral components may serve as unique targets for antiviral strategies. In the case of HIV-1, early electron microscopy (EM) work established that in T cell, which are a natural host for HIV-1, virus assembly takes place at the plasma membrane (PM), whereas in macrophages, another natural host cell type, virus particles assemble and accumulate within apparently intracellular compartments.

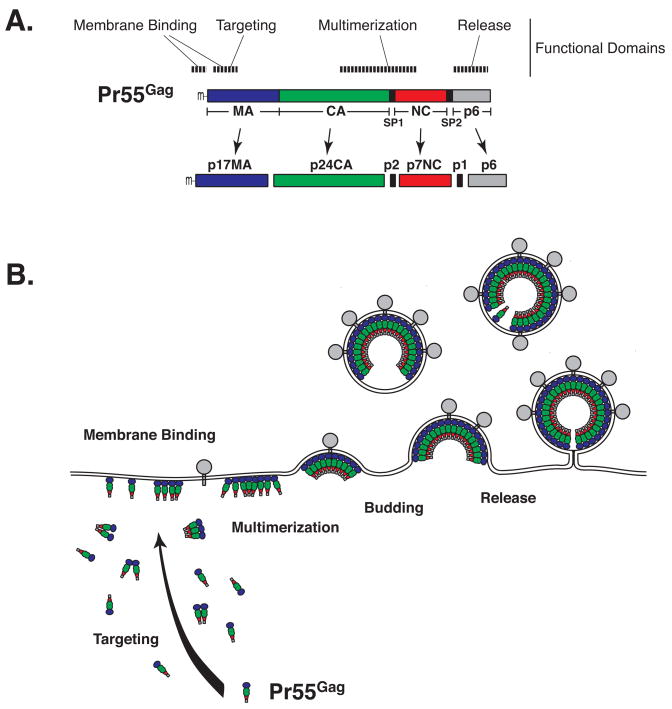

Retrovirus particle production is driven by a viral structural protein called Gag [1, 2]. In the case of HIV-1, Gag is synthesized as a precursor polyprotein Pr55Gag (Fig. 1). Pr55Gag is N-myristylated and consists of four major structural domains: matrix (MA), capsid (CA), nucleocapsid (NC), and p6, with two spacer peptides, SP1 and SP2 (Fig. 1). Upon virus release, the viral protease (PR) cleaves Pr55Gag and gives rise to mature Gag proteins, p17MA, p24CA, p7NC, and p6 from the four major domains of Pr55Gag. Virus particle production is a multistep process that includes: 1) Gag targeting to the site of virus assembly, 2) binding of Gag to lipid membrane bilayer, 3) Gag multimerization, and 4) budding and release of nascent virus particles. Gag association with the lipid bilayer is mediated by the N-terminal myristate moiety and a highly basic region in MA, whereas Gag multimerization is driven by both CA-CA interaction and RNA-mediated bridging by NC. Notably, membrane binding of Gag is regulated by a mechanism known as the myristoyl switch. In this mechanism, the exposure and sequestration of the myristate moiety is affected by the level of Gag multimerization [3]; when Gag multimerizes, the N-terminal myristate becomes exposed from the MA globular domain, resulting in higher affinity for membrane. Consistent with this model, a number of studies showed that some degree of Gag multimerization precedes membrane binding although extensive higher-order Gag multimerization occurs on the membrane (for a review, see [4]). The order in which CA- and NC-mediated multimerization takes place remains to be definitively established. Budding/release of virus particles from cellular membranes is driven by cellular protein complexes called ESCRTs (endosomal sorting complexes required for transport) recruited by p6 to the site of virus assembly (for reviews, see [5–7]).

Figure 1.

Organization of Gag domains and steps in HIV-1 particle production. A) The major Gag domains, MA, CA, NC, and p6, as well as the spacer peptides SP1 and SP2 are shown. N-terminal myristate moiety is shown as (m-). Positions of functional domains are also indicated. Upon virus release, the viral protease cleaves Pr55Gag and gives rise to individual mature Gag proteins from four major domains of Pr55Gag. B) Major steps of virus particle assembly and release are shown.

Compared to Gag membrane binding, Gag multimerization, and budding, molecular mechanisms regulating the earlier step of Gag targeting to the sites of virus assembly is less well understood. In this review, I will describe and discuss our current understanding of three interrelated aspects of Gag targeting: 1) the potential involvement of endosomal pathways in HIV-1 Gag trafficking, 2) Gag interactions with PM domains that serve as destinations for Gag and sites of virus assembly, and 3) roles played by a PM-specific lipid, phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2], in specific localization of Gag at the PM.

Potential Roles Played by Endosomal Trafficking Pathways

Involvement of endosomal factors in HIV-1 assembly

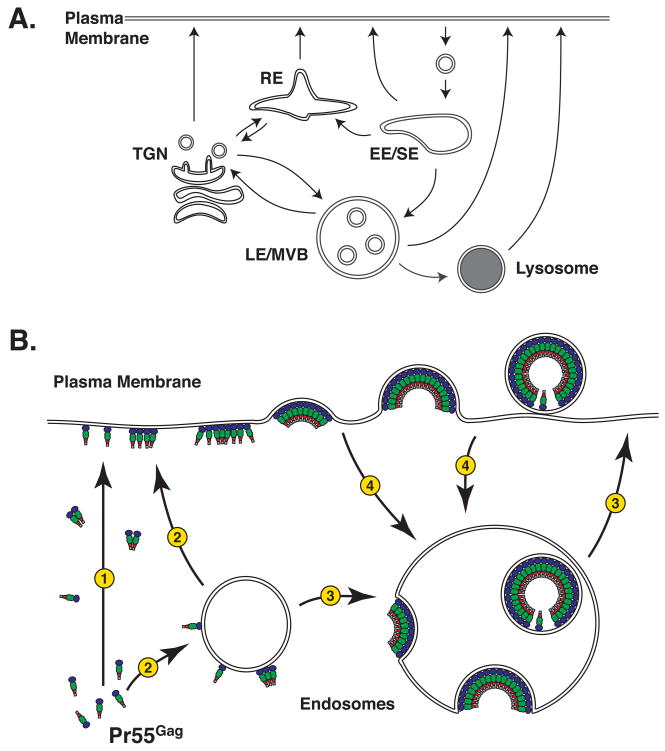

As noted above, early EM studies demonstrated that a majority of assembled or assembling HIV-1 particles localize at the PM in infected T cells, whereas in macrophages, virus particles are mostly concentrated in apparently internal compartments [8, 9]. Several studies have found that these virus-positive compartments in macrophages are enriched with markers characteristic of late endosomes/multivesicular bodies (LE/MVB) [10–12] (although the conclusion of these studies that HIV-1 assembles in MVB in macrophages has recently been challenged as discussed below). Furthermore, fluorescent and electron microscopy of several tissue culture cell lines (e.g., 293T cells) observed that wild type (WT) Gag localizes not only at the PM but also at the LE/MVB [13, 14]. These observations have suggested that endosomal pathways might serve as trafficking routes of Gag or assembled particles (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Potential involvement of endosomal trafficking pathways in Gag targeting. A) The major organelles and routes in endosomal trafficking pathways are shown. EE/SE, early endosome/sorting endosome; LE/MVB, late endosome/multivesicular body; RE, recycling endosome; TGN, trans-Golgi network. B) Potential Gag trafficking routes. Gag may be either directly targeted to the PM (pathway 1) or transported to the PM through endosomal trafficking routes (pathway 2). Along the latter pathway, Gag may form virus particles inside the endosomal lumen and later get released extracellularly by fusion of endosomes with the PM (pathway 3). However, the interpretation of Gag localization data is complicated because virus particles accumulated in endosomes may have been formed at the PM and internalized before being released to the extracellular space (pathway 4).

Consistent with the putative roles of endosomal pathways in HIV-1 particle production, a number of factors involved in endosomal trafficking and recycling (Fig. 2) have been reported to affect HIV-1 particle production and Gag localization. For example, HIV-1 Gag was shown to interact with the AP-1, AP-2, and AP-3 adaptor complexes that normally function in transport between endosomes and Golgi, endocytosis from the PM, and trafficking from early/sorting endosomes (EE/SE) to LE/MVB, respectively [15–17]. Whereas expression of a mutant AP-2 subunit markedly increased virus release [15], inhibition of interactions between Gag and AP-1 or AP-3 reduced virus particle production substantially, suggesting that these adaptor complexes are actively involved in HIV-1 assembly [16, 17]. Perturbation of the ESCRT complexes that are responsible for MVB formation was shown to cause accumulation of HIV-1 Gag on endosomal membranes in COS cells [18, 19]. RNAi-mediated depletion of Rab9 that regulates endosomal recycling caused HIV-1 Gag accumulation at the LE/MVB and blocked virus replication in a HeLa-derived cell line [20, 21]. Inhibition of a trans-Golgi-network (TGN)-associated ubiquitin ligase, hPOSH, also blocked Gag trafficking to the PM in HeLa cells [22]. GGA and Arf proteins that regulate a number of aspects in intracellular membrane trafficking modulate Gag localization and virus release [23]. Intracellular Ca2+ perturbation that is known to induce fusion of the LE/MVB and lysosomes with other organelles and the PM stimulates virus release to the extracellular space [24, 25]. In addition to HIV-1, studies on Gag proteins of other retroviruses, such as murine leukemia virus (MLV), human T cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1), and Mason-Pfizer monkey virus (MPMV) provide evidence for the active involvement of endosomal recycling in Gag transport [26–30]. Altogether, these reports suggest that at least some aspects of the endosomal pathways play some role in Gag trafficking.

Gag trafficking along endosomal pathways

As described later, several reports have suggested that virus particles accumulating in LE/MVB-like compartments in macrophages could be released from cells through fusion between these compartments and the PM [11, 31, 32]. As data obtained with tissue culture cell lines such as 293T cells also suggest the involvement of endosomal trafficking in virus production as discussed above, it was postulated that regardless of cell types, Gag first localizes to endosomes and then traffics to the PM (Fig. 2B, pathway 2) instead of targeting directly to the PM (Fig. 2B, pathway 1). Along this pathway, Gag may form virus particles inside the endosomal lumen and later get released extracellularly by fusion of endosomes with the PM (Fig. 2B, pathway 3). However, the interpretation of Gag localization data is complicated because virus particles accumulated in endosomes may have been formed at the PM and internalized before being released to the extracellular space (Fig. 2B, pathway 4). Indeed, when HIV-1 Gag is expressed in the absence of a viral accessory protein Vpu, newly formed virus particles accumulate at the cell surface and eventually become endocytosed [33–35]. Therefore, it was unclear whether a Gag population associated with endosomes represents an intermediate of a productive pathway for extracellular virus particle production (directed toward the PM) or an abortive pathway (internalized from the PM) that may trap and eventually degrade assembled virions.

To address this point, several groups have conducted studies using experimental procedures with various scales of time resolution. These include monitoring localization of GFP-tagged Gag (Gag-GFP) for several hours, specific labeling of newly synthesized Gag with fluorescent dyes, and pulse-chase analyses combined with organelle fractionation [24, 25, 36–40].

Studies that analyzed 293T cells expressing Gag-GFP over 4–20 h after transfection have shown that Gag localization at the PM precedes Gag accumulation in intracellular compartments [37, 38]. The intracellular Gag localization in 293T cells was abolished by expression of endocytosis inhibitors [38], indicating that Gag detected in endosomes in these experiments originates from the PM. However, other studies that monitored single COS cells over time after microinjection of Gag-GFP-encoding DNA or release from cycloheximide block detected a Gag population in intracellular compartments before massive PM localization occurs [25, 39]. Thus, these long-term monitoring studies suggest that a majority of Gag accumulated in endosomes in later time points are likely derived from the PM, but did not exclude the possibility that some nascent Gag may transit through intracellular compartments before forming puncta on the cell surface. It is of note that, as it can take tens of minutes for a GFP molecule to become fluorescent [41], localization of newly synthesized Gag may be poorly represented in fluorescence microscopy in these studies.

To examine specifically the localization of newly synthesized Gag, two studies used a biarsenic-based imaging technique. In this technique, a protein of interest tagged with a tetracysteine (TC) motif can be specifically labeled in live cells with fluorescent biarsenic dyes added extracellularly [42, 43]. In both studies [25, 40], TC-tagged Gag was expressed in HeLa cells, and nascent Gag was visualized by similar protocols. However, one study concluded that nascent Gag appears at the PM without forming cytoplasmic intermediates [40], whereas the other reached an opposite conclusion [25]. In addition to this discrepancy, in both studies, cells were stained with the biarsenic dye for one hour, making it difficult to determine the localization of nascent Gag.

Biochemical experiments provide the clearest information on Gag localization at the earliest time points after Gag synthesis available thus far. In these experiments, Gag-expressing 293T cells were metabolically pulse-labeled for 10–15 min and fractionated by iodixanol gradients to the PM, LE/MVB, and other fractions [24, 36]. Data from both studies indicate that newly synthesized Gag is present both at the PM and the LE/MVB fractions [24, 36]. When chased over 5 h, the PM-associated Gag is either released extracellularly or internalized and trafficked to the LE/MVB compartments [36], confirming the PM origin for a majority of endosome-associated Gag. Thus, the remaining question is whether the LE/MVB-associated nascent Gag contributes to virus particle production at the PM.

This question has been addressed by pharmacological alteration of LE/MVB trafficking. Microtubule disruption is known to inhibit movement of the LE/MVB. When Gag-expressing 293T cells were treated with microtubule depolymerizing agents, the efficiency of virus release and the level of Gag association to the PM were unaffected [36, 38]. Similarly, treatment of cells with U18666A, which increases cholesterol in the LE/MVB and blocks recruitment of kinesin to the LE/MVB, stalled the LE/MVB at the juxtanuclear area, but did not affect virus particle release [38]. Furthermore, Gag derivatives artificially targeted to endosomes formed virus particles in endosomes but failed to be released extraellularly in 293T cells [38]. Therefore, currently available data suggest that, at least in 293T cells, Gag molecules and virus particles associated with the LE/MVB are unlikely to contribute to the extracellular virus production.

As described earlier, however, a number of cellular proteins associated with various endosomal routes are implicated in extracellular virus particle production. It is possible that Gag may be transported along an endosomal trafficking pathway other than that from the LE/MVB to the PM. It is also conceivable that, depending on the cell types or cellular conditions such as Gag expression and cell stimulation levels, Gag may alternately use a direct targeting pathway and an endosomal transport pathway to reach the PM. Consistent with this possibility, it has been observed recently that a Gag mutant targeted to the LE/MVB in T cells still achieves near-WT levels of extracellular particle production (Joshi and Freed, submitted).

PM Domains that Serve as Sites of Virus Assembly

HIV-1 assembly in PM invaginations

In HIV-1-infected macrophages, a vast majority of assembled virus particles have been found at intracellular membranous compartments that contain MHC Class II, LAMP1, and tetraspanins such as CD63 and CD81, all of which are associated with the LE/MVB [10–12, 31, 32]. A number of cell types, including macrophages, are known to release the intraluminal vesicles of the LE/MVB to the extracellular space as exosomes by fusion of the PM and the limiting membrane of the LE/MVB. Therefore, virus particles budded into the lumen of intracellular compartments in macrophages were also thought to be released in the same pathway [44, 45]. Consistent with this hypothesis, virus particles in supernatants of infected macrophages were shown to contain LE/MVB markers as well [11, 32]. However, as in the case with 293T cells, even in macrophages, Gag localization at the PM was observed earlier than its localization at intracellular compartments [38]. These results suggest that Gag and virus particles found in intracellular compartments of macrophages may also have originated at the PM. Indeed, a substantial fraction of the intracellular virus-containing compartments (VCC) in macrophages have turned out to be actually large and complex invaginations of the PM and not LE/MVBs or other endosomes [46–48] (Fig. 3). This population of VCC has thin tubular membrane structures that connect the lumen of the VCC to the extracellular space [46]. Another subset of the VCC appears to be not connected to the extracellular space but still stays separated from acidic compartments such as LE/MVBs [47]. As similar intracellular compartments enriched with tetraspanins CD9, CD53, and CD81 are present in uninfected macrophages [46], it is likely that the VCC is not induced de novo by infection. As cytochalasin D blocks formation of the VCC [38], actin polymerization likely plays an important role in its biogenesis. Another cellular factor, annexin II, has been implicated in virion maturation inside VCC [49]. However, the molecular mechanisms that drive the formation of the VCC and accumulate Gag and virus particles to these compartments remain to be elucidated.

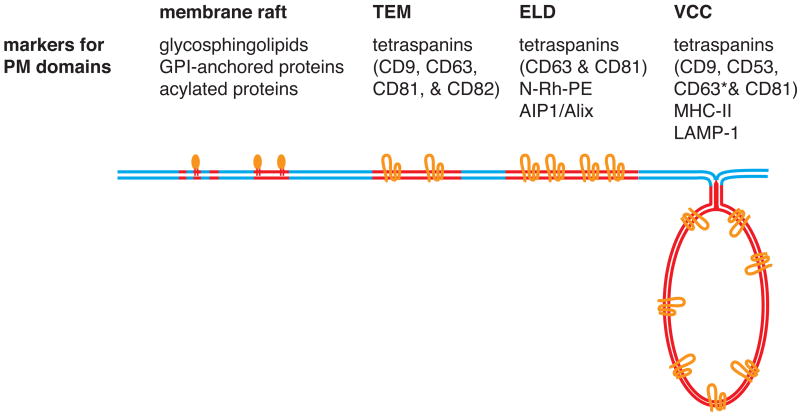

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of plasma membrane domains involved in HIV-1 assembly. TEM, tetraspanin-enriched microdomain; ELD, endosome-like domain; VCC, virus-containing compartment. Markers for each domain are listed. See text for more detail.

It is thought that infected macrophages serve as long-term virus reservoir and contribute to persistence of HIV [50–52]. In this regard, the VCC may play an important role in protecting virions within it from humoral immune responses [46] due to its semi-intracellular nature. Whether virions in the VCC are eventually released and, if so, what triggers such release are currently under active investigation in several laboratories. Intriguingly, recent reports suggest that contact of infected macrophages with CD4+ T cells triggers accumulation of Gag or virus particles at the macrophage-T cell junction [53, 54]. These findings support a hypothesis that VCC plays a major role in cell-to-cell virus transmission from macrophages to T cells.

HIV-1 assembly in PM microdomains

As described above, in most cell types, the PM or its invaginations serve as the major site of virus assembly. The PM and other cellular membranes are known to consist of various microdomains that contain specific sets of proteins and lipids (Fig. 3). Among them, membrane rafts, also known as lipid rafts, enriched with cholesterol and sphingolipids have been under intense scrutiny because of their potential involvement in many cellular functions and yet-unclear nature (for reviews, see [55–61]). HIV-1 assembly also likely involves membrane rafts. HIV-1 particle membrane is highly enriched with raft lipids such as cholesterol and sphingolipids [62–64] and raft-specific proteins [65]. Furthermore, biochemical and microscopy-based analyses have demonstrated that Gag and Env colocalize or cofractionate with raft-specific markers but not with nonraft proteins [65–73]. Current consensus on the nature of membrane rafts is that each raft may be highly dynamic, unstable, and small (10–50 nm) but could coalesce to form a large domain upon stimulation [56–60]. Therefore, assembly of an HIV-1 particle that is 100–150 nm in diameter would likely take place not in a single raft, but in large raft aggregates or PM areas relatively enriched with rafts. At the same time, it is also conceivable that assembling Gag multimers might stabilize otherwise unstable rafts at the virus assembly sites. Fractionation experiments have shown that higher-order Gag multimerization mediated by NC is dispensable for Gag-raft association defined by detergent resistance [74]. However, it is still possible that Gag oligomers or lattices formed underneath the PM induce clustering of “raftphilic” lipids and create conditions favorable for raft formation or stabilization.

HIV-1 particle formation has also been observed to associate with other PM domains (Fig. 3). As noted above, tetraspanins such as CD63 are often used as markers of the LE/MVB. However, at least a subpopulation of tetraspanins form clusters known as tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEM) at the cell surface [75]. It has been observed that HIV-1 Gag and Env highly colocalize with TEM [76]. In Jurkat T cells, Gag has been found to localize at a PM domain termed endosome-like domain (ELD) that is enriched with tetraspanins and a few other molecules usually associated with endosomes [77, 78]. Tetraspanins are also found on virus particles that are released from T cells [79–82], supporting the idea that the TEM/ELD serve as sites for HIV-1 assembly. Notably, the VCC observed in HIV-1-infected macrophages are highly enriched with tetraspanins such as CD9 and CD81 [46]. Therefore, the VCC may be formed by invagination of PM domains originating from TEMs or ELDs.

Other retroviruses have also been observed to associate with lipid rafts and TEM/ELDs during virus assembly [66, 72, 83–85], indicating that association with these PM microdomains is a common process shared by retroviruses. As suggested by an early study[86], however, different retroviruses may utilize different subsets of PM microdomains.

A number of reports support the notion that association of HIV-1 components with PM microdomains of virus producing cells benefits HIV-1 replication in several aspects. Cellular cholesterol depletion that disrupts membrane rafts and TEM/ELD [55, 61, 77, 87] has been shown to inhibit particle production of HIV-1 and other retroviruses [70, 72] by reducing efficiencies of Gag membrane binding and multimerization [88]. Incorporation of an unsaturated myristate analog to Gag N terminus in place of myristate, which blocks association with membrane rafts without affecting general membrane binding of Gag, diminishes virus particle production [89]. These results suggest that association of Gag with membrane microdomains facilitates virus particle assembly. Membrane microdomains also modulate infectivity of assembled particles. Cholesterol in producer cells and virions is essential for infectivity of progeny virions [70, 90–95], whereas incorporation of tetraspanins into virions has either no or negative impact on infectivity [82, 96]. Altogether, Gag association with PM microdomains likely plays multiple roles in production of infectious HIV-1 virions at the PM.

In addition to particle production, virus transmission from producer to target cells may also be facilitated by PM microdomains. It has been observed that assembling or assembled virus particles concentrate at the contact site between infected and uninfected T cells. This contact site, known as the virological synapse (VS) ([97, 98]; for reviews, see [99, 100]), is enriched with membrane raft components and tetraspanins [80, 101]. Cholesterol depletion and anti-tetraspanin antibodies markedly reduced VS formation [80, 101]. Consistent with a role for TEM in VS formation, in HeLa cells, clustering of a tetraspanin CD9 by a specific antibody induces massive accumulation of this tetraspanin along with Gag at cell-cell junctions [102]. These data suggest that both these microdomains may be actively involved in accumulation of virus particles and Gag multimers to the VS as vehicles for virus components or assembled particles. Alternatively, areas enriched with these PM microdomains at the surface of virus-producing cells may function as preferred contact sites for a target cell. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the initial phase of VS formation appears to involve a rear-end structure resembling uropod [103]. It has been observed that uropods are enriched with membrane rafts [104, 105] and tetraspanins (Llewellyn and AO, unpublished) as well as a number of cell adhesion molecules [106]. Therefore, it is conceivable that PM microdomains facilitate formation of preformed platform at uropods where virus particles assemble or accumulate, which eventually constitutes the infected-cell-side of the VS.

A Mechanism that Localizes Gag Specifically to the PM

Gag localization signals

What is the Gag determinant that targets this protein to the PM where virus particles assemble? Mutagenesis studies have shown that two regions in MA are important for PM localization of Gag. In HeLa and T cells, amino acid substitutions in either the highly basic region (amino acids 16–31) or amino acids 84–88 in the MA domain lead to virus particle formation at the LE/MVB [10, 107–110]. Interestingly, studies of revertants emerged in T cell cultures inoculated with these MA mutants demonstrated a functional link between the highly basic region and amino acids 84–88 in MA [111]. As the highly basic region but not amino acids 84–88 is exposed on the surface of HIV-1 MA molecule [112], it is likely that the former serves as a PM-targeting signal. Perhaps, mutations in amino acids 84–88 may affect indirectly the structure of the MA domain and thereby its membrane interaction. Interestingly, the N-terminal 6 amino acids of Gag, which corresponds to N- myristylation signal, is capable of targeting Gag to the PM when most of MA is deleted [113]. Therefore, the highly basic domain may be required for the PM localization of Gag in the full-length context. Structural studies showed that the highly basic region along with other MA basic amino acids forms a basic patch [112, 114]. Such basic patches in MA are highly conserved among retroviruses [115] underlining the importance of the MA basic sequences.

As discussed below in more detail, the MA basic sequence likely forms a specific binding site for PI(4,5)P2, an acidic phospholipid specifically localized at the cytoplasmic leaflet of the PM. The interaction between this lipid and the MA domain likely targets Gag to the PM. In addition, this interaction is also postulated to direct Gag to membrane rafts within the PM [116]. As for Gag localization to another membrane domain, ELD, it requires not only membrane binding of Gag but also higher order multimerization mediated by NC [78].

Gag derivatives with MA basic domain mutations appear to localize specifically to the LE/MVB rather than binding promiscuously to the multiple organelles [10, 109] (AO unpublished). What facilitates localization of these Gag mutants is currently unknown. It is conceivable that internalization of these Gag mutants from the PM is accelerated due to the lack of interaction with a PM-specific Gag retention factor. Alternatively, it is possible that there is another cryptic localization signal that directly targets Gag to the LE/MVB in the absence of the PM localization signal. NC may play a role in either case, as mutations in the NC zinc finger region prevented Gag localization to the perinuclear compartments [117]. It is currently unclear, however, whether this region is directly involved as a localization signal, or whether the NC mutations affect other NC functions such as RNA binding and Gag multimerization, which may play key roles in Gag trafficking to the LE/MVB. As mentioned above, p6 interacts with proteins associated with ESCRT complexes, TSG101 and Alix, which localize and function at the LE/MVB. It is unlikely, however, that p6-ESCRT interaction determines localization of Gag with the MA basic domain mutations, as p6 mutations do not change Gag localization patterns [10, 40].

Role of PI(4,5)P2 in HIV-1 assembly

Although Gag associates with membrane rafts and TEM/ELD at the PM, it is unknown whether these membrane domains play an active role in recruiting Gag to the PM. Replacing the Gag N-terminal myristate moiety with an unsaturated analog disrupts Gagraft association and leads to localization of Gag to the ER in addition to the PM [89]. However, these results may simply indicate that the unsaturated myristate analog confers to Gag an affinity for the ER membrane and do not necessarily suggest that rafts are involved in the PM targeting of native Gag. Moreover, cellular cholesterol depletion does not appear to affect PM-specific localization of Gag [88]. Thus, it is unlikely that membrane rafts and TEM/ELD are directly involved in Gag recruitment to the PM. Then, what would be the cellular determinant(s) for the PM localization of Gag? Recent findings suggest that a PM phospholipid, PI(4,5)P2, is a determinant for PM-specific Gag localization.

PI(4,5)P2 belongs to a family of lipids known as phosphoinositides. All phosphoinositides have an inositol ring in their head group. They differ from each other in the number and positions of phosphate residues on this inositol ring. Each phosphoinositide has a specific subcellular localization [118, 119]. For example, in most cell types, PI(4,5)P2 localizes on the cytoplasmic leaflet of the PM, PI(3)P at the early endosome, and PI(3,5)P2 at the late endosome. A number of cellular proteins that bind the cytoplasmic leaflet of organelle membranes interact directly with phosphoinositides. These proteins have basic domains such as pleckstrin homology (PH) and epsin N-terminal homology domains, which electrostatically interact with the head group of phosphoinositides [118–122]. Importantly, some basic domains bind specifically one phosphoinositide species and, as a result, proteins with such domains are localized specifically to the organelles containing this particular phosphoinositide species. For example, the PH domain of phospholipase C delta 1 (PLCδ 1) specifically recognizes PI(4,5)P2 so that a GFP chimera bearing this PH domain (PH PLCδ1GFP) detects the presence of PI(4,5)P2 on the PM [123, 124]. On the surface of these protein domains, basic amino acids form a basic pocket, patch, or protrusion that defines specificity for phosphoinositide species [120–122].

Involvement of PI(4,5)P2 in HIV-1 particle production has been shown using two different types of PI(4,5)P2 perturbation in tissue culture cell lines. First, when polyphosphoinositide 5-phosphatase IV (5-ptaseIV) was overexpressed in HeLa cells expressing a HIV-1 molecular clone, cellular PI(4,5)P2 was depleted and Gag either mislocalized to perinuclear compartments or failed to bind any membrane [125, 126]. Second, when an intracellular compartment enriched with PI(4,5)P2 was induced by expression of Arf6(Q67L), a constitutively active form of Arf6 that regulates a PI(4,5)P2- producing enzyme, HIV-1 Gag was relocalized to this new compartment [126]. Likely due to altered Gag localization, both types of PI(4,5)P2 perturbation resulted in several fold reduction in virus release efficiency [125, 126]. Inhibition of virus particle production by perturbation of PI(4,5)P2 was also observed for HIV-2 [127], murine leukemia virus [64], and Mason Pfizer Monkey Virus [128]. Therefore, it is likely that PI(4,5)P2 plays important roles in assembly of retroviruses in general.

By what mechanisms does PI(4,5)P2 regulate Gag localization to the PM? Based on biochemical and structural studies, it is likely that direct binding of Gag to PI(4,5)P2 localizes Gag to the PM due to the PM-specific localization of this lipid. As mentioned above, Gag has a basic region within MA, which is important for Gag localization at the PM [10, 107–110]. Structural studies have demonstrated that this region, along with a few other basic amino acids in other parts of MA, forms a highly basic patch on the surface of MA. This patch likely serves as an interface for head groups of acidic phospholipids [112, 114]. It has been shown previously in an in vitro Gag assembly study that interaction between Gag and IP5, an inositol derivative structurally related to the head group of PI(4,5)P2, is important for the proper Gag assembly [129]. A mathematical modeling study also predicted that MA interacts with PI(4,5)P2 preferentially compared with other acidic phospholipids [130]. Recently, four groups used different approaches to demonstrate binding of HIV-1 Gag to PI(4,5)P2 experimentally[64, 116, 125, 131]. 1) By assessing the accessibility of a lysine- modifying reagent, Kvaratskhelia et al. identified two lysine residues (Lys 29 and 31) that are inaccessible in non-myristylated Gag mixed with a water-soluble form of PI(4,5)P2 with truncated acyl chains [131]. Notably, double mutations of these residues have been shown to relocalize Gag and virus assembly to the LE/MVB [10, 109]. 2) Summers’ group used NMR to solve the structure of a complex between water-soluble PI(4,5)P2 and myristylated MA [116]. Interestingly, this study observed that PI(4,5)P2 binding increases the exposure of the N-terminal myristate moiety [116]. Therefore, PI(4,5)P2 appears to increase the affinity of Gag for lipid bilayers not only by acting as a membrane anchor but also by triggering the myristoyl switch [116]. Similar data were observed using HIV-2 MA although the effects on myristate exposure were smaller [127]. These NMR studies also showed that myristylated MA from HIV-1 and HIV-2 binds PI(4,5)P2 more efficiently than other phosphoinositides. 3) We established a Gag- PI(4,5)P2 binding assay using full-length myristylated Gag and liposome-associated PI(4,5)P2 with natural acyl chains [125]. The results obtained with this assay suggest that Gag binding to membrane-associated PI(4,5)P2 is dependent on a high density of negative charges and configuration of phosphate groups on the inositol head group of PI(4,5)P2. Furthermore, double mutations at MA residues Lys 29 and 31 reduced PI(4,5)P2-dependent liposome binding, again suggesting the key role played by these basic amino acids. 4) The Ott, Mothes, and Wenk laboratories conducted detailed analysis of the lipid content of retrovirus particles [64]. This study demonstrated that PI(4,5)P2 is highly enriched on HIV-1 and MLV membranes compared to the PM of virus-producing cells. Notably, when VLPs were produced by a Gag derivative lacking a majority of MA including the highly basic patch but still retaining the N-terminal myristylation signal, this VLP preparation showed a two-fold reduction in the levels of virion-associated PI(4,5)P2, suggesting that MA-PI(4,5)P2 interaction takes place not just in vitro but also in cells. Altogether, these results suggest that a direct interaction between PI(4,5)P2 and the MA domain, in particular its highly basic region, largely explains PI(4,5)P2-dependent PM localization of Gag. Notably, some amino acid substitutions in the highly basic region increase Gag binding to liposomes that do not contain PI(4,5)P2 (V. Chukkapalli, J. Oh, and A.O., unpublished observation). Therefore, the MA highly basic region may play dual and opposing roles in regulating Gag binding to the PM.

A number of reports have suggested that PI(4,5)P2 is enriched in specific domains of the PM [132–137], which may serve as initial membrane binding sites for Gag. On the other hand, it is also possible that equilibrated association between PI(4,5)P2 and Gag in multimers might create PI(4,5)P2-enriched microdomains at the PM, which in turn facilitates Gag recruitment to the PM. The observation that PI(4,5)P2 is enriched in retroviral membranes [64] supports the presence of these PI(4,5)P2 -enriched microdomains. However, relationships between PI(4,5)P2-enriched domains and other microdomains as well as their physiological significance in the process of virus assembly remain to be determined. Intriguingly, in the NMR structure of the PI(4,5)P2 -MA complex, MA was found to sequester the unsaturated 2′-acyl chain of PI(4,5)P2, leaving the saturated 1′-acyl chain and the MA N-terminal myristate exposed outside of the complex [116]. Based on this finding, it has been proposed that Gag binding to PI(4,5)P2 targets this complex to membrane rafts due to exposed saturated acyl chains [116].

Future Perspective

A number of studies implicate the endosomal trafficking pathway in some aspects of HIV-1 assembly. However, currently available evidence suggests that a majority of virus particles assemble at the PM, in particular, at its membrane domains. These domains are exposed on the cell surface in most cell types including T cells, but deeply invaginated into the cytoplasm in macrophages. Although a substantial amount of information has been gained in the last 5 years, toward better understanding of the HIV-1 assembly at the plasma membrane, a number of outstanding questions remain to be answered in next 5–10 years. Some of these questions are listed below.

1) Where in cytoplasm is Gag synthesized and how does it reach to the PM?

To determine the route to the PM taken by Gag, it is essential to determine where the trafficking of Gag molecules initiates. Organelle fractionation experiments suggest that Gag associates with both the PM and endosomes within 10 minutes after its synthesis [36, 117], but these data do not provide information as to the location of ribosomes translating Gag. Are they close to the PM or any other membranes? Or are they near cytoskeletal networks? This issue is closely linked to trafficking of viral RNA molecules encoding Gag. Accumulating evidence suggests that nuclear export and/or cytoplasmic trafficking of viral RNAs play important roles in virus particle assembly [138–140]. Microscopy analyses of viral RNA distribution have suggested that Gag synthesis and interaction with genomic RNA occur near microtubule organizing centers (MTOC) [141, 142]. Consistent with a possible role for microtubules in transport of nascent Gag, unassembled Gag has been observed to localize along microtubules [143]. It was also reported that a microtubule-associated, plus-end-directed motor protein, KIF4, plays a key role in Gag distribution at early time points [39, 144]. Depletion of KIF4 caused aggregation of Gag at the perinuclear non-endosomal compartments [39]. Similarly, depletion of SOCS1 that was reported to associate with MTOC [145] also induced Gag aggregation at the perinuclear region [146]. Microtubule depolymerization, which disrupts both plus- and minus-end-directed movement along microtubules, showed no impact on virus production from 293T cells [38]. Therefore, unidirectional movement to the plus end of microtubules might be needed for distribution of viral RNA or newly synthesized Gag when the minus-end directed flow is also present.

2) How does Gag behave immediately after binding to the PM but before assembly?

A TIRF microscopy study [147] has shown that virus particles assemble at rather static PM sites to which Gag accumulates gradually. However, tracking of single Gag molecules using a super high-resolution microscopy method demonstrated that there are free Gag molecules bound to the PM in addition to Gag in assembling clusters [148]. The nature of PM sites where Gag initially binds and trajectories of free Gag molecules to the assembly sites remain to be determined.

3) What regulates the VCC?

Further characterization of the VCC is necessary to address mechanisms that regulate formation of this compartment and release of virus particles inside the VCC. What targets Gag and/or virus particles to the VCC in macrophages also remains to be elucidated. In this regard, it is intriguing that PI(4,5)P2 is enriched in VCC (Deneka and Marsh, personal communication; Chukkapalli, Goo and AO, unpublished data). It is conceivable that PI(4,5)P2 associated with the VCC serves not only as a determinant for Gag localization but also as a regulator of cytoskeleton rearrangement or membrane dynamics, both of which could affect states of VCC.

4) What are the relationships between PM microdomains?

Despite the large number of enveloped viruses reported to associate with PM microdomains [71], the organization and interplay among microdomains used by exiting viruses are not well understood. As discussed earlier, HIV-1 Gag associates with membrane rafts, TEM, and ELD, but relationships between these membrane domains and roles each of these domains play in the HIV-1 assembly process remain to be elucidated. The PI(4,5)P2-MA interaction has been proposed to trigger Gag association with membrane rafts [116], whereas both Gag membrane binding and higher-order multimerization have been shown to be important for ELD association [78]. Thus, it is conceivable that Gag associates with various microdomains in a sequential manner during assembly steps. Recent evidence indicates that HIV and influenza use different subsets of membrane domains [102]. Furthermore, an early study suggested that, even within retroviruses, MLV and RSV use different subsets of PM domains [86]. Whether this is due to specific interactions of viral proteins with host factors unique to each domain, perhaps PI(4,5)P2 or tetraspanins, is a key question toward better understanding of PM microdomain organization exploited by enveloped viruses. Additionally, whether factors incorporated into virions due to microdomain interactions affect early phases of virus life cycle is of further interest.

5) What are the mechanisms regulating VS formation?

Targeting to or association with the PM microdomains appear to play key roles in formation of VS. In addition, cytoskeletons are also likely involved [97, 98, 149, 150]. However, exact roles for the PM microdomains and cytoskeletons in cell-to-cell virus transmission at the VS have yet to be elucidated. Relationships between the PM microdomains and recently reported cytonemes and tunneling nanotubes, filopodia-like structures that transmit retrovirus particles, are also unknown [151]. To gain insights into these issues, it is essential to delineate a series of molecular events that take place before and during the VS formation process in spatial and temporal manner.

6) Are PM microdomains involved in host defense?

Recent reports demonstrated that cells have defense mechanisms against enveloped viruses, which inhibit release of nascent virus particles from the PM. Viperin inhibits influenza virus release through alteration of membrane rafts [152], whereas tetherin/CD317/BST-2 and CAML reportedly promote retention of newly formed retrovirus particles at the PM and eventual internalization [153–155]. Interestingly, tetherin has a GPI anchor, which presumably targets this protein to membrane rafts [156]. Furthermore, a cholesterol-binding compound, amphotericin B methyl ester, inhibits the function of Vpu [157], a viral protein that counteract restriction imposed by tetherin or CAML [35, 153–155, 158]. Thus, PM microdomains where particle assembly takes place are possibly a major battleground between enveloped viruses and host cells. Whether formation, dispersal, or internalization of these microdomains play key roles in host defense mechanisms remains to be determined.

Addressing questions listed here will bring us better understanding of entire mechanisms regulating HIV-1 assembly at the PM domains. As this phase of the virus life cycle has major implications in production of progeny virions and transmission to next target cells, detailed information on these points will likely provide us with insights into new strategies for suppressing HIV replication and pathogenesis.

Executive Summary

Introduction

- Virus particle formation of HIV-1 is driven by a multidomain protein Gag.

- Early electron microscopy studies demonstrated that a majority of assembled or assembling HIV-1 particles localize at the plasma membrane (PM) in infected T cells, whereas in macrophages, virus particles are mostly concentrated in internal compartments.

Potential Roles Played by Endosomal Trafficking Pathways

- Fluorescent and electron microscopy of several tissue culture cell lines observed that Gag localizes not only at the PM but also at the late endosome/multivesicler bodies (LE/MVB).

- However, currently available data support that, at least in 293T cells, Gag molecules and virus particles associated with the LE/MVB are derived from the PM and unlikely to contribute to the extracellular virus production.

- Nevertheless, a number of factors involved in endosomal trafficking and recycling have been reported to affect HIV-1 particle production and Gag localization.

- Therefore, it is still conceivable that at least some aspects of the endosomal pathways play some role in Gag trafficking.

PM Domains that Serve as Sites of Virus Assembly

- A substantial fraction of the intracellular virus-containing compartments (VCC) in macrophages is actually large and complex invaginations of the PM and not LE/MVBs or other endosomes even though it is enriched with tetraspanins.

- HIV-1 assembly in other cell types takes place in PM microdomains such as membrane rafts, tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEM), and endosome-like domains (ELD). The relationships between these PM domains are not well understood.

- These PM microdomains likely facilitate HIV-1 particle assembly and release.

- In addition, these PM microdomains are implicated in cell-to-cell HIV transmission at virological synapse (VS).

A Mechanism that Localizes Gag Specifically to the PM

- Mutagenesis studies have shown that the highly basic region in MA is required for the PM-specific localization of Gag.

- Structural studies have demonstrated that this region forms a highly basic patch on the surface of MA. This patch likely serves as an interface for head groups of acidic phospholipids.

- Perturbation of a PM-specific acidic phospholipids, PI(4,5)P2, inhibits proper Gag localization to the PM and diminishes HIV-1 particle production.

- Studies using protein footprinting, NMR, liposome-binding, and viral membrane lipidomics demonstrated that MA, in particular its basic region, directly interacts with PI(4,5)P2, and this interaction likely facilitates Gag localization at the PM.

Future Perspective

- Toward better understanding of the HIV-1 assembly at the plasma membrane, a number of outstanding questions remain to be answered. Less well understood topics include: very early phase of Gag trafficking, regulation of VCC and VS, relationships between PM micodomains, and roles of PM domains in suppression of virus particle production.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. Eric Freed and members of the Ono laboratory for helpful discussions and critical review of this manuscript. I also thank 6 anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions. I regret that, due to a policy of the journal, I could not always adequately cite early studies by colleagues who pioneered the field reviewed here. Work in this area in my laboratory is supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI071727) and American Heart Association (0850133Z).

References

- 1.Adamson CS, Freed EO. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly, release, and maturation. Adv Pharmacol. 2007;55:347–387. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(07)55010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamson CS, Jones IM. The molecular basis of HIV capsid assembly--five years of progress. Rev Med Virol. 2004;14:107–121. doi: 10.1002/rmv.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3**.Tang C, Loeliger E, Luncsford P, Kinde I, Beckett D, Summers MF. Entropic switch regulates myristate exposure in the HIV-1 matrix protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:517–522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305665101. This paper provided structural evidence for the myristyl switch model. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein KC, Reed JC, Lingappa JR. Intracellular destinies: degradation, targeting, assembly, and endocytosis of HIV Gag. AIDS Rev. 2007;9:150–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bieniasz PD. Late budding domains and host proteins in enveloped virus release. Virology. 2006;344:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demirov DG, Freed EO. Retrovirus budding. Virus Res. 2004;106:87–102. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morita E, Sundquist WI. Retrovirus budding. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:395–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.102350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelderblom HR. Assembly and morphology of HIV: potential effect of structure on viral function. Aids. 1991;5:617–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orenstein JM, Meltzer MS, Phipps T, Gendelman HE. Cytoplasmic assembly and accumulation of human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 in recombinant human colony-stimulating factor-1-treated human monocytes: an ultrastructural study. J Virol. 1988;62:2578–2586. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2578-2586.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ono A, Freed EO. Cell-type-dependent targeting of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly to the plasma membrane and the multivesicular body. J Virol. 2004;78:1552–1563. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1552-1563.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelchen-Matthews A, Kramer B, Marsh M. Infectious HIV-1 assembles in late endosomes in primary macrophages. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:443–455. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200304008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raposo G, Moore M, Innes D, et al. Human macrophages accumulate HIV-1 particles in MHC II compartments. Traffic. 2002;3:718–729. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.31004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nydegger S, Foti M, Derdowski A, Spearman P, Thali M. HIV-1 egress is gated through late endosomal membranes. Traffic. 2003;4:902–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0854.2003.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherer NM, Lehmann MJ, Jimenez-Soto LF, et al. Visualization of retroviral replication in living cells reveals budding into multivesicular bodies. Traffic. 2003;4:785–801. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15**.Batonick M, Favre M, Boge M, Spearman P, Honing S, Thali M. Interaction of HIV-1 Gag with the clathrin-associated adaptor AP-2. Virology. 2005;342:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.08.001. Refs. 15–17 and 21–23 provided evidence supporting that factors associated with endosomal trafficking pathways play active roles in HIV-1 Gag localization and assembly. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16**.Camus G, Segura-Morales C, Molle D, et al. The clathrin adaptor complex AP-1 binds HIV-1 and MLV Gag and facilitates their budding. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3193–3203. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-12-1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17**.Dong X, Li H, Derdowski A, et al. AP-3 directs the intracellular trafficking of HIV-1 Gag and plays a key role in particle assembly. Cell. 2005;120:663–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18*.Goff A, Ehrlich LS, Cohen SN, Carter CA. Tsg101 control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag trafficking and release. J Virol. 2003;77:9173–9182. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9173-9182.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19*.von Schwedler UK, Stuchell M, Muller B, et al. The protein network of HIV budding. Cell. 2003;114:701–713. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00714-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brass AL, Dykxhoorn DM, Benita Y, et al. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science. 2008;319:921–926. doi: 10.1126/science.1152725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21**.Murray JL, Mavrakis M, McDonald NJ, et al. Rab9 GTPase is required for replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1, filoviruses, and measles virus. J Virol. 2005;79:11742–11751. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11742-11751.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22**.Alroy I, Tuvia S, Greener T, et al. The trans-Golgi network-associated human ubiquitin-protein ligase POSH is essential for HIV type 1 production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1478–1483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408717102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23**.Joshi A, Garg H, Nagashima K, Bonifacino JS, Freed EO. GGA and Arf proteins modulate retrovirus assembly and release. Mol Cell. 2008;30:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24**.Grigorov B, Arcanger F, Roingeard P, Darlix JL, Muriaux D. Assembly of infectious HIV-1 in human epithelial and T-lymphoblastic cell lines. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:848–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.017. This study and ref. 36 conducted fractionation experiments indicating that a subset of Gag is associated with endosomes early after its synthesis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Perlman M, Resh MD. Identification of an intracellular trafficking and assembly pathway for HIV-1 gag. Traffic. 2006;7:731–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9219.2006.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26*.Basyuk E, Galli T, Mougel M, Blanchard JM, Sitbon M, Bertrand E. Retroviral genomic RNAs are transported to the plasma membrane by endosomal vesicles. Dev Cell. 2003;5:161–174. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27*.Blot V, Perugi F, Gay B, et al. Nedd4.1-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent recruitment of Tsg101 ensure HTLV-1 Gag trafficking towards the multivesicular body pathway prior to virus budding. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2357–2367. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28*.Dorweiler IJ, Ruone SJ, Wang H, Burry RW, Mansky LM. Role of the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 PTAP motif in Gag targeting and particle release. J Virol. 2006;80:3634–3643. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3634-3643.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29*.Sfakianos JN, Hunter E. M-PMV capsid transport is mediated by Env/Gag interactions at the pericentriolar recycling endosome. Traffic. 2003;4:671–680. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30*.Sfakianos JN, LaCasse RA, Hunter E. The M-PMV cytoplasmic targeting-retention signal directs nascent Gag polypeptides to a pericentriolar region of the cell. Traffic. 2003;4:660–670. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer B, Pelchen-Matthews A, Deneka M, Garcia E, Piguet V, Marsh M. HIV interaction with endosomes in macrophages and dendritic cells. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2005;35:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen DG, Booth A, Gould SJ, Hildreth JE. Evidence that HIV budding in primary macrophages occurs through the exosome release pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52347–52354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harila K, Prior I, Sjoberg M, Salminen A, Hinkula J, Suomalainen M. Vpu and Tsg101 regulate intracellular targeting of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 core protein precursor Pr55gag. J Virol. 2006;80:3765–3772. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.3765-3772.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harila K, Salminen A, Prior I, Hinkula J, Suomalainen M. The Vpu-regulated endocytosis of HIV-1 Gag is clathrin-independent. Virology. 2007;369:299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neil SJ, Eastman SW, Jouvenet N, Bieniasz PD. HIV-1 Vpu promotes release and prevents endocytosis of nascent retrovirus particles from the plasma membrane. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e39. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36**.Finzi A, Orthwein A, Mercier J, Cohen EA. Productive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly takes place at the plasma membrane. J Virol. 2007;81:7476–7490. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00308-07. This study and ref. 24 conducted fractionation experiments indicating that a subset of Gag is associated with endosomes early after its synthesis. This study further demonstrated that Gag accumulated later in endosomes is derived from the PM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37*.Hubner W, Chen P, Del Portillo A, Liu Y, Gordon RE, Chen BK. Sequence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Gag localization and oligomerization monitored with live confocal imaging of a replication-competent, fluorescently tagged HIV-1. J Virol. 2007;81:12596–12607. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01088-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38**.Jouvenet N, Neil SJ, Bess C, et al. Plasma membrane is the site of productive HIV-1 particle assembly. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040435. This paper demonstrated that Gag populations associated with LE/MVB originate from the PM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39**.Martinez NW, Xue X, Berro RG, Kreitzer G, Resh MD. Kinesin KIF4 regulates intracellular trafficking and stability of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag polyprotein. J Virol. 2008;82:9937–9950. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00819-08. This study reported that Gag is localized in non-endosomal perinuclear compartment at early time points. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40*.Rudner L, Nydegger S, Coren LV, Nagashima K, Thali M, Ott DE. Dynamic fluorescent imaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag in live cells by biarsenical labeling. J Virol. 2005;79:4055–4065. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4055-4065.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L, Patel HN, Lappe JW, Wachter RM. Reaction progress of chromophore biogenesis in green fluorescent protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4766–4772. doi: 10.1021/ja0580439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griffin BA, Adams SR, Tsien RY. Specific covalent labeling of recombinant protein molecules inside live cells. Science. 1998;281:269–272. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin BR, Giepmans BN, Adams SR, Tsien RY. Mammalian cell-based optimization of the biarsenical-binding tetracysteine motif for improved fluorescence and affinity. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1308–1314. doi: 10.1038/nbt1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gould SJ, Booth AM, Hildreth JE. The Trojan exosome hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10592–10597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1831413100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pelchen-Matthews A, Raposo G, Marsh M. Endosomes, exosomes and Trojan viruses. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46**.Deneka M, Pelchen-Matthews A, Byland R, Ruiz-Mateos E, Marsh M. In macrophages, HIV-1 assembles into an intracellular plasma membrane domain containing the tetraspanins CD81, CD9, and CD53. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:329–341. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609050. Refs.46–48 showed that sites of virus assembly in macrophages are not LE/MVBs. Refs. 46 and 48 concluded that these compartments are deep invaginations of the PM, whereas ref. 47 concluded that they are a new subset of endosomes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47**.Jouve M, Sol-Foulon N, Watson S, Schwartz O, Benaroch P. HIV-1 buds and accumulates in “nonacidic” endosomes of macrophages. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48**.Welsch S, Keppler OT, Habermann A, Allespach I, Krijnse-Locker J, Krausslich HG. HIV-1 Buds Predominantly at the Plasma Membrane of Primary Human Macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e36. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49*.Ryzhova EV, Vos RM, Albright AV, Harrist AV, Harvey T, Gonzalez-Scarano F. Annexin 2: a novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag binding protein involved in replication in monocyte-derived macrophages. J Virol. 2006;80:2694–2704. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2694-2704.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kedzierska K, Crowe SM. The role of monocytes and macrophages in the pathogenesis of HIV-1 infection. Curr Med Chem. 2002;9:1893–1903. doi: 10.2174/0929867023368935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51*.Sharova N, Swingler C, Sharkey M, Stevenson M. Macrophages archive HIV-1 virions for dissemination in trans. Embo J. 2005;24:2481–2489. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verani A, Gras G, Pancino G. Macrophages and HIV-1: dangerous liaisons. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:195–212. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53*.Gousset K, Ablan SD, Coren LV, et al. Real-time visualization of HIV-1 GAG trafficking in infected macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000015. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54*.Groot F, Welsch S, Sattentau QJ. Efficient HIV-1 transmission from macrophages to T cells across transient virological synapses. Blood. 2008;111:4660–4663. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown DA, London E. Structure and function of sphingolipid- and cholesterol-rich membrane rafts. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17221–17224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Edidin M. The state of lipid rafts: from model membranes to cells. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2003;32:257–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hancock JF. Lipid rafts: contentious only from simplistic standpoints. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:456–462. doi: 10.1038/nrm1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jacobson K, Mouritsen OG, Anderson RG. Lipid rafts: at a crossroad between cell biology and physics. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:7–14. doi: 10.1038/ncb0107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kusumi A, Koyama-Honda I, Suzuki K. Molecular dynamics and interactions for creation of stimulation-induced stabilized rafts from small unstable steady-state rafts. Traffic. 2004;5:213–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.0178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mayor S, Rao M. Rafts: scale-dependent, active lipid organization at the cell surface. Traffic. 2004;5:231–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simons K, Toomre D. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:31–39. doi: 10.1038/35036052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62**.Aloia RC, Tian H, Jensen FC. Lipid composition and fluidity of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope and host cell plasma membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:5181–5185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5181. Refs. 62–64 analyzed lipid contents of retrovirus membrane and provided a strong support for the model that retroviruses assemble in specific mebrane domains. In addition, ref. 64 provided evidence for Gag-PI(4,5)P2 interaction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63**.Brugger B, Glass B, Haberkant P, Leibrecht I, Wieland FT, Krausslich HG. The HIV lipidome: a raft with an unusual composition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2641–2646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511136103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64**.Chan R, Uchil PD, Jin J, et al. Retroviruses human immunodeficiency virus and murine leukemia virus are enriched in phosphoinositides. J Virol. 2008;82:11228–11238. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00981-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65**.Nguyen DH, Hildreth JE. Evidence for budding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 selectively from glycolipid-enriched membrane lipid rafts. J Virol. 2000;74:3264–3272. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3264-3272.2000. This is the first paper suggesting that HIV-1 assembles in the membrane rafts. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66*.Feng X, Heyden NV, Ratner L. Alpha interferon inhibits human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 assembly by preventing Gag interaction with rafts. J Virol. 2003;77:13389–13395. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.13389-13395.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67*.Halwani R, Khorchid A, Cen S, Kleiman L. Rapid localization of Gag/GagPol complexes to detergent-resistant membrane during the assembly of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2003;77:3973–3984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.3973-3984.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68*.Holm K, Weclewicz K, Hewson R, Suomalainen M. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Assembly and Lipid Rafts: Pr55(gag) Associates with Membrane Domains That Are Largely Resistant to Brij98 but Sensitive to Triton X-100. J Virol. 2003;77:4805–4817. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4805-4817.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69*.Lindwasser OW, Resh MD. Multimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag promotes its localization to barges, raft-like membrane microdomains. J Virol. 2001;75:7913–7924. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.7913-7924.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70**.Ono A, Freed EO. Plasma membrane rafts play a critical role in HIV-1 assembly and release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13925–13930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241320298. This paper and ref. 89 provided evidence suggesting that membrane rafts play an important role in HIV-1 assembly. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ono A, Freed EO. The role of lipid rafts in virus replication. In: Roy Polly., editor. Advances in Virus Research: Virus Structure and Assembly. Elsevier; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72*.Pickl WF, Pimentel-Muinos FX, Seed B. Lipid rafts and pseudotyping. J Virol. 2001;75:7175–7183. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.7175-7183.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rousso I, Mixon MB, Chen BK, Kim PS. Palmitoylation of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein is critical for viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13523–13525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240459697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74*.Ono A, Waheed AA, Joshi A, Freed EO. Association of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag with membrane does not require highly basic sequences in the nucleocapsid: use of a novel Gag multimerization assay. J Virol. 2005;79:14131–14140. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14131-14140.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Levy S, Shoham T. The tetraspanin web modulates immune-signalling complexes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:136–148. doi: 10.1038/nri1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76**.Nydegger S, Khurana S, Krementsov DN, Foti M, Thali M. Mapping of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains that can function as gateways for HIV-1. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:795–807. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508165. Refs. 76 and 77 provided the first evidence that HIV-1 assembly takes place in PM microdomains enriched with tetraspanins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77**.Booth AM, Fang Y, Fallon JK, Yang JM, Hildreth JE, Gould SJ. Exosomes and HIV Gag bud from endosome-like domains of the T cell plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:923–935. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78*.Fang Y, Wu N, Gan X, Yan W, Morrell JC, Gould SJ. Higher-order oligomerization targets plasma membrane proteins and HIV gag to exosomes. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79*.Chertova E, Chertov O, Coren LV, et al. Proteomic and biochemical analysis of purified human immunodeficiency virus type 1 produced from infected monocyte-derived macrophages. J Virol. 2006;80:9039–9052. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01013-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80*.Jolly C, Sattentau QJ. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly, budding, and cell-cell spread in T cells take place in tetraspanin-enriched plasma membrane domains. J Virol. 2007;81:7873–7884. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01845-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ott DE. Cellular proteins detected in HIV-1. Rev Med Virol. 2008;18:159–175. doi: 10.1002/rmv.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82*.Sato K, Aoki J, Misawa N, et al. Modulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity through incorporation of tetraspanin proteins. J Virol. 2008;82:1021–1033. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01044-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83*.Mazurov D, Heidecker G, Derse D. HTLV-1 Gag protein associates with CD82 tetraspanin microdomains at the plasma membrane. Virology. 2006;346:194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84*.Mazurov D, Heidecker G, Derse D. The inner loop of tetraspanins CD82 and CD81 mediates interactions with human T cell lymphotrophic virus type 1 Gag protein. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3896–3903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85*.Medina G, Pincetic A, Ehrlich LS, et al. Tsg101 can replace Nedd4 function in ASV Gag release but not membrane targeting. Virology. 2008;377:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86*.Bennett RP, Wills JW. Conditions for copackaging rous sarcoma virus and murine leukemia virus Gag proteins during retroviral budding. J Virol. 1999;73:2045–2051. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2045-2051.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Silvie O, Charrin S, Billard M, et al. Cholesterol contributes to the organization of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains and to CD81-dependent infection by malaria sporozoites. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1992–2002. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88*.Ono A, Waheed AA, Freed EO. Depletion of cellular cholesterol inhibits membrane binding and higher-order multimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag. Virology. 2007;360:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89**.Lindwasser OW, Resh MD. Myristoylation as a target for inhibiting HIV assembly: unsaturated fatty acids block viral budding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13037–13042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212409999. This paper and ref. 70 provided evidence suggesting that membrane rafts play an important role in HIV-1 assembly. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90*.Campbell S, Gaus K, Bittman R, Jessup W, Crowe S, Mak J. The raft-promoting property of virion-associated cholesterol, but not the presence of virion-associated Brij 98 rafts, is a determinant of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity. J Virol. 2004;78:10556–10565. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10556-10565.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91*.Campbell SM, Crowe SM, Mak J. Virion-associated cholesterol is critical for the maintenance of HIV-1 structure and infectivity. Aids. 2002;16:2253–2261. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211220-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92*.Guyader M, Kiyokawa E, Abrami L, Turelli P, Trono D. Role for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 membrane cholesterol in viral internalization. J Virol. 2002;76:10356–10364. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10356-10364.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93*.Liao Z, Graham DR, Hildreth JE. Lipid rafts and HIV pathogenesis: virion-associated cholesterol is required for fusion and infection of susceptible cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:675–687. doi: 10.1089/088922203322280900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94*.Waheed AA, Ablan SD, Mankowski MK, et al. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by amphotericin B methyl ester: selection for resistant variants. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28699–28711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95*.Zheng Y-H, Plemenitas A, Linneman T, Fackler OT, Peterlin BM. Nef increases infectivity of HIV via lipid rafts. Current Biology. 2001;11:875–879. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96*.Ruiz-Mateos E, Pelchen-Matthews A, Deneka M, Marsh M. CD63 is not required for production of infectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in human macrophages. J Virol. 2008;82:4751–4761. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02320-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97**.Igakura T, Stinchcombe JC, Goon PK, et al. Spread of HTLV-I between lymphocytes by virus-induced polarization of the cytoskeleton. Science. 2003;299:1713–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1080115. Refs. 97 and 98 provided initial evidence demonstrating the presence of virological synapses. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98**.Jolly C, Kashefi K, Hollinshead M, Sattentau QJ. HIV-1 Cell to Cell Transfer across an Env-induced, Actin-dependent Synapse. J Exp Med. 2004;199:283–293. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jolly C, Sattentau QJ. Retroviral spread by induction of virological synapses. Traffic. 2004;5:643–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Piguet V, Sattentau Q. Dangerous liaisons at the virological synapse. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:605–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI22812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101*.Jolly C, Sattentau QJ. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virological synapse formation in T cells requires lipid raft integrity. J Virol. 2005;79:12088–12094. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.12088-12094.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102*.Khurana S, Krementsov DN, de Parseval A, Elder JH, Foti M, Thali M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and influenza virus exit via different membrane microdomains. J Virol. 2007;81:12630–12640. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01255-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103*.Chen P, Hubner W, Spinelli MA, Chen BK. Predominant mode of human immunodeficiency virus transfer between T cells is mediated by sustained Env-dependent neutralization-resistant virological synapses. J Virol. 2007;81:12582–12595. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00381-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gomez-Mouton C, Abad JL, Mira E, et al. Segregation of leading-edge and uropod components into specific lipid rafts during T cell polarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9642–9647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171160298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Millan J, Montoya MC, Sancho D, Sanchez-Madrid F, Alonso MA. Lipid rafts mediate biosynthetic transport to the T lymphocyte uropod subdomain and are necessary for uropod integrity and function. Blood. 2002;99:978–984. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sanchez-Madrid F, del Pozo MA. Leukocyte polarization in cell migration and immune interactions. Embo J. 1999;18:501–511. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Freed EO, Orenstein JM, Buckler-White AJ, Martin MA. Single amino acid changes in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein block virus particle production. J Virol. 1994;68:5311–5320. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5311-5320.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hermida-Matsumoto L, Resh MD. Localization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag and Env at the plasma membrane by confocal imaging. J Virol. 2000;74:8670–8679. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8670-8679.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ono A, Orenstein JM, Freed EO. Role of the Gag Matrix Domain in Targeting Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Assembly. J Virol. 2000;74:2855–2866. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2855-2866.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yuan X, Yu X, Lee TH, Essex M. Mutations in the N-terminal region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein block intracellular transport of the Gag precursor. J Virol. 1993;67:6387–6394. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6387-6394.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ono A, Huang M, Freed EO. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix revertants: effects on virus assembly, Gag processing, and Env incorporation into virions. J Virol. 1997;71:4409–4418. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4409-4418.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112*.Hill CP, Worthylake D, Bancroft DP, Christensen AM, Sundquist WI. Crystal structures of the trimeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein: implications for membrane association and assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3099–3104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Perez-Caballero D, Hatziioannou T, Martin-Serrano J, Bieniasz PD. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix inhibits and confers cooperativity on gag precursor-membrane interactions. J Virol. 2004;78:9560–9563. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9560-9563.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rao Z, Belyaev AS, Fry E, Roy P, Jones IM, Stuart DI. Crystal structure of SIV matrix antigen and implications for virus assembly. Nature. 1995;378:743–747. doi: 10.1038/378743a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115*.Conte MR, Matthews S. Retroviral matrix proteins: a structural perspective. Virology. 1998;246:191–198. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116**.Saad JS, Miller J, Tai J, Kim A, Ghanam RH, Summers MF. Structural basis for targeting HIV-1 Gag proteins to the plasma membrane for virus assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11364–11369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602818103. This paper is one of the first studies that described the direct interaction between Gag and PI(4,5)P2. This study provided a detailed structural information on the MA-PI(4,5)P2 complex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Grigorov B, Decimo D, Smagulova F, et al. Intracellular HIV-1 Gag localization is impaired by mutations in the nucleocapsid zinc fingers. Retrovirology. 2007;4:54. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Downes CP, Gray A, Lucocq JM. Probing phosphoinositide functions in signaling and membrane trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Roth MG. Phosphoinositides in constitutive membrane traffic. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:699–730. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00033.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.DiNitto JP, Cronin TC, Lambright DG. Membrane recognition and targeting by lipid-binding domains. Sci STKE 2003. 2003:re16. doi: 10.1126/stke.2132003re16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hurley JH, Meyer T. Subcellular targeting by membrane lipids. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:146–152. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lemmon MA. Phosphoinositide recognition domains. Traffic. 2003;4:201–213. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2004.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Stauffer TP, Ahn S, Meyer T. Receptor-induced transient reduction in plasma membrane PtdIns(4,5)P2 concentration monitored in living cells. Curr Biol. 1998;8:343–346. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Varnai P, Balla T. Visualization of phosphoinositides that bind pleckstrin homology domains: calcium- and agonist-induced dynamic changes and relationship to myo-[3H]inositol-labeled phosphoinositide pools. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:501–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]