“Salicornia europaea” increases acetylcholinesterase (AChE) accompanied by salt accumulation during their growth. The plant acetylcholine (ACh)-mediated system in Salicornia could be responsible for transport of ions through channels in a manner similar to the animal systems. In this study, Salicornia AChE gene was identified by RT-PCR using degenerate primers designed based on previously cloned maize and siratro AChE genes. The full-length cDNA of Salicornia AChE was 1,536 nucleotides, encoding a 387-residue protein that includes a 28-residue signal sequence. In silico research presumed that Salicornia AChE is targeted to the secretory pathway via the endoplasmic reticulum.

The plant Salicornia europaea L. is a strong halophyte, which can survive over 3% NaCl.1,2 In general, halophytes often accumulate saline ions to high level in shoot or root.3–7 These plants may regulate ion concentrations in shoot or root by several strategies. Some halophytes may regulate root ion concentrations by ion exclusion at the root cortex,8 or accumulate glycinebetaine in the cytoplasm following salt accumulation for the purpose of osmoregulation.9–12 Salicornia plants increase acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in the root and the lower part of the stem following Na+ and Cl− accumulation.13,14 Furthermore, high histochemical AChE activity was detected in the cortex of roots and stems of Salicornia plants including endodermal cells around the vascular system, and strongly in endodermis, cortex and epidermis at the bifurcation of lateral roots from the main root.14

The ACh—ACh-receptor (AChR)—AChE system, that is “the ACh-mediated system”, is a well-known signal transmission system in animals.15–17 ACh has been recently identified in a number of non-neuronal tissues in animals, fungi, bacteria and plants.18,19 Both ACh and AChE activity has been widely recognized in plants.20–26 The ACh-mediated system in plants might propagate membrane depolarization and might achieve cell-to-cell transport of the hormone and other substances between plant cells.27,28 Thus, we proposed the ACh-mediated system in Salicornia plants may function to elimination of excessive salt from epidermal cells of roots by cell-to-cell transport.

To understand the function of ACh-mediated system in plants, Salicornia AChE gene was identified by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using designed primers based on our cloned maize and siratro AChE genes, and introduced in tobacco plants. Then activity of Salicornia AChE was confirmed. Function of AChE in Salicornia plants was predicted by computer assisted in silico research.

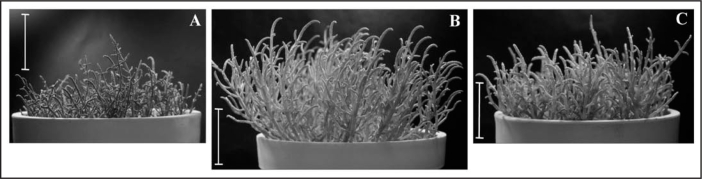

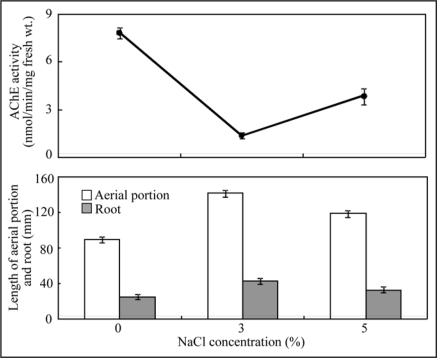

The effect of salts on Salicornia plant growth was determined after 2 months salt treatment. The results are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. The poorest growth was observed in the absence of salt. The best growth was obtained in 3% NaCl. Length of aerial portion and root, fresh weight and dry weight were all great in 3% NaCl compared to 0% and 5% NaCl plots. AChE activity was the lowest when growth was the most robust, such as in 3% NaCl. Conversely, AChE activity was high, when plant growth was poor, such as in 0% and 5% NaCl. The AChE activity was contrast to plant growth. There was a strong relationship between plant growth and AChE activity in Salicornia plants (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Effect of NaCl on growth in Salicornia plants

| NaCl concentration (%) | |||

| 0 | 3 | 5 | |

| Plant length | |||

| Aerial portion | 89.8 ± 3.2c | 141.7 ± 3.5a | 119.1 ± 3.7b |

| Root | 25.0 ± 2.8b | 42.9 ± 3.1a | 32.7 ± 3.4ab |

| Fresh weight | 652 ± 24c | 3106 ± 129a | 1469 ± 53b |

| Dry weight | 149 ± 13c | 794 ± 33a | 288 ± 18b |

Values are the means ± standard error of the mean of ten different experiments with three replicated measurements. Means followed by the same letters were not significantly different at p < 0.05, according to Tukey test.

Figure 1.

Growth conditions under the different NaCl concentrations. Plants were grown for 2 months at NaCl conditions adjusted to 0, 3 and 5%, respectively. (A) 0% NaCl, (B) 3% NaCl, (C) 5% NaCl.

Figure 2.

Effects of NaCl concentrations on plant growth and AChE activity in Salicornia plants. Plants were grown for 2 months at NaCl conditions adjusted to 0, 3 and 5%, respectively. Vertical bars indicate standard error of the mean of ten different experiments with three replicated measurements.

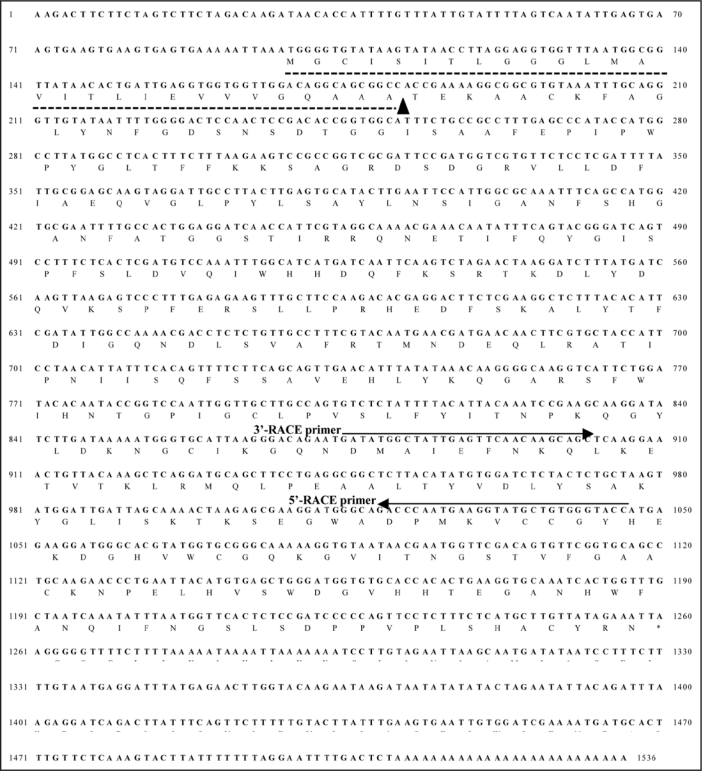

The partial cDNA sequence of Salicornia AChE gene was determined using degenerate primers. These primers set yielded PCR product of 418 bp for Salicornia AChE gene. Then, this PCR product was sequenced. The full-length cDNA for Salicornia AChE gene was cloned by 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) and 3′-RACE with gene-specific primers. The 5′-RACE (1,046 bp) and 3′-RACE (662 bp) products were amplified and sequenced. The DNA sequences obtained at the 5′-end of 5′-RACE and the 3′-end of 3′-RACE were used as PCR primers to obtain the full-length cDNA clone of Salicornia AChE gene. The determined full-length nucleotide sequences of Salicornia AChE consisted of 1,536 bp encoded 387 amino acid residues (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence of the siratro AChE cDNA. Dotted underline shows a signal peptide at N-terminus from Met-1 to Ala-28. Arrowhead indicates putative signal peptide cleavage site. Two oligonucleotide primers that was used for RACE-PCR is shown as arrows over the nucleotide sequence.

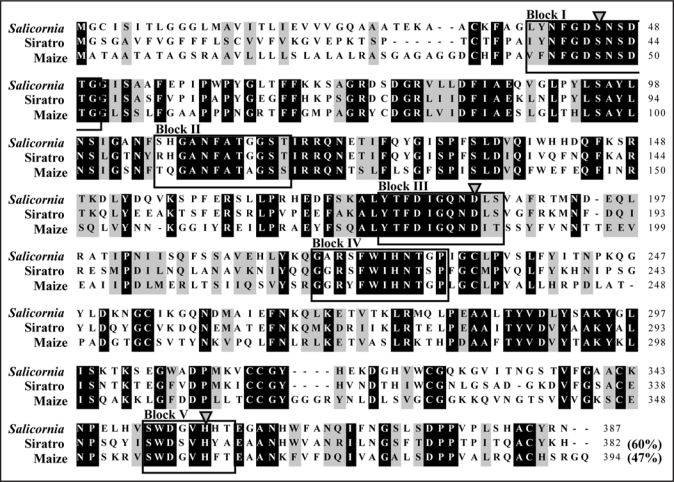

The protein domain architecture derived from the deduced amino acid sequence of Salicornia AChE was examined by computer-associated protein family analysis using the protein family database Pfam (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Pfam). This indicated that the Salicornia AChE contains a conserved putative lipase GDSL family domain at residues 39 to 368, similar to maize and siratro AChE (Fig. 4). Each of the five motif blocks is characteristic of the lipase GDSL family in bacteria and plants.29–31 The deduced amino acid sequence of Salicornia AChE shared 47% and 60% identities with those of maize and siratro AChEs. The catalytic Ser/Asp(Glu)/His triads of the enzymes belonging to the lipase GDSL family were found in some of these proteins, and the sequences surrounding the consensus residues are well conserved.29–31 Therefore, the putative catalytic triad for Salicornia AChE, Ser-45/Asp-184/His-355 (indicated by this study), siratro AChE, Ser-41/Asp-180/His-350,32 and maize AChE, Ser-47/Asp-185/His-360,33 can be deduced by superimposing the sequences on those of the lipase GDSL family enzymes (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of Salicornia, siratro and maize AChEs. Conserved amino acid residues are highlighted in black. Residues not identical, but similar to the conserved one, are highlighted in gray. The blocks of sequences conserved in the lipase GDSL family enzymes and the putative catalytic triad Ser/Asp(Glu)/His residues in the lipase GDSL family enzymes, which were presumed previously,32–34 are indicated by boxes and arrowheads, respectively. The accession numbers used in the analysis are as follows: siratro AChE, AB294246; maize AChE, AB093208.

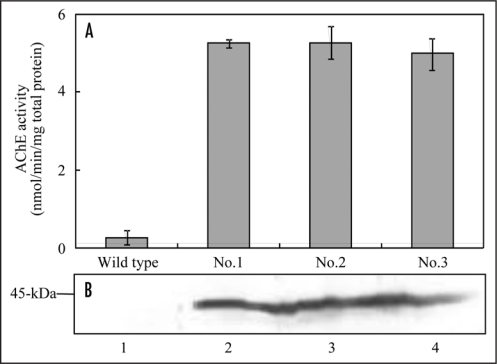

The Salicornia AChE gene was introduced behind the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (35S) to confirm AChE activity of gene product of Salicornia AChE gene. The 35S::Salicornia AChE was transformed into tobacco. The 35S::Salicornia AChE transgenic tobacco plants (T0 generation) showed approximately 18.3–19.4 fold higher AChE activities compared with wild type plants (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, molecular mass of Salicornia AChE protein in transgenic tobacco plant was estimated to be approximately 44-kDa by western blot analysis, similar to that of maize AChE (Fig. 5B). Thus, Salicornia AChE gene encodes AChE protein in Salicornia plant.

Figure 5.

AChE activity and expression in transgenic tobacco plants. (A) AChE activity in the transgenic tobacco plants. AChE activities in leaves of transgenic plants (T0 generation) were measured by the DTNB method. Acetylthiocholine was used as substrate. (B) Western blot analysis of transgenic tobacco plants. The total protein was extracted from leaves of transgenic plants (T0 generation). The samples were separated on a 12.5% SDS-PAGE, blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with maize AChE antibody. Lane 1, wild type; lane 2, 35S::Salicornia AChE No.1; lane 3, 35S::Salicornia AChE No.2; lane 4, 35S::Salicornia AChE No.3.

The N-terminal signal peptides were predicted by the SignalP program34 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-2.0/) and checked using the TargetP program35 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/). The N terminus of the deduced Salicornia AChE precursor protein sequence contains a 28-residue signal sequence, which routes the protein to a secretory pathway with a probability of 93%. Furthermore the SOSUI program (http://bp.nuap.nagoya-u.ac.jp/sosui/sosui_submit.html), which discriminates between membrane and soluble proteins, showed that mature Salicornia AChE do not contain any likely transmembrane helical regions, which are features of proteins that associate with the lipid bilayers of the cell membrane. Thus Salicornia AChE might function in the extracellular spaces similar to maize AChE36 and some isoforms of animal AChE. In addition, high AChE activity was detected in the root and the lower part of the stem following Na+ and Cl− accumulation.13,14 These results suggest that Salicornia AChE may function to elimination of excessive salt in the extracellular spaces of epidermal cells of roots.

The Salicornia seeds for cultivation were harvested around Lake Notori in the eastern region of Hokkaido, October 2007 and sown in April 2008. The cultivation and treatment of Salicornia plants were performed with same method as Sagane et al.33 who used Shimose's culture solution37 with some modification. At 4 weeks of sowing, the culture solution for salt treatment was adjusted to 0%, 3% and 5% NaCl. To prevent salt accumulation on the surface of the soil and to maintain the salt concentrations, the soil was washed with 3 liters of tap water, and was newly irrigated every week with 1 liter of salt water. The cultures were used for measurement of the plant growth, AChE activity and molecular analysis after 8 weeks of treatment. The plants grown at 3% NaCl condition were used for molecular analysis.

AChE activity for molecular analysis was measured by the DTNB method following precisely in the same way of Yamamoto et al.32 Plant materials were cut in 2 mm lengths and incubated at 30°C for 10 min in vials containing 300 µl of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) with 24 µl of 100 mM neostigmine bromide or 24 µl of distilled water for a control. After 10 min incubation, 500 µl of 12.5 mM acetylthiocholine (ASCh) chloride as a substrate of AChE was added, and the solution was incubated at 30°C for 2 h. Following incubation, 300 µl of the solution was transferred to a vial, and 1,425 µl of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and 75 µl of 10 mM DTNB in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) were added. The A412 was read after 1 min. All experiments were corrected for the control value described above.

The maize AChE cDNA excluded the signal peptide sequence was constructed in an overexpression vector, pET23a (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA). The recombinant plasmids were used to transform E. coli strain, Rosetta-gamiB (DE3) pLysS (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA). Overexpression was induced by 0.05 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside at room temperature in a bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system. After induction overnight, the E. coli cells were harvested and crashed by sonication with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 200 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA. The overexpressed recombinant protein was eluted from SDS-PAGE gels. The purified recombinant maize AChE was used to raise antibodies in rabbits according to standard procedure. The antisera were then purified by antigen-affinity chromatography, and stored at 4°C in the presence of 0.1% sodium azide.

Total RNA was prepared from 0.1 g of shoots of 3% NaCl treated Salicornia plants using the RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen, KJ Venlo, the Netherlands) and removed residual genomic DNA with TURBO DNA-free kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). The cDNA was synthesized from RNA samples using the SuperScript II First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen Carlabad, CA). Degenerate primers for Salicornia AChE gene were designed based on conserved sequences in each AChE gene from siratro and maize (AChE-DF, 5′-GGA GGR AGG TMM TTC TGG ATW CAC AAC AC-3′; AChE-DR, 5′-ART GMA CRC IGT CCC ARC TYA-3′). Using these primers together with cDNA as a template, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out by rTaq DNA polymerase (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). The PCR product was ligated into pT7blue T-vector (MERCK, Darmstadt, Germany) and DNA sequencing was conducted using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit and an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The full-length cDNA cloning of Salicornia AChE was carried out by 3′- and 5′-RACE techniques using a SMART RACE cDNA amplification kit (BD Biosciences CLONTECH, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Gene-specific primers were designed from the obtained partial cDNA sequence of Salicornia AChE (Fig. 2), and 3′ and 5′ ends of the cDNA fragments were amplified with KOD DNA polymerase (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). RACE products were purified and cloned into the pT7blue T-vector and sequenced on both strands. Finally, the full-length cDNA sequence encoding Salicornia AChE was identified by primer walking.

The full-length Salicornia AChE cDNA sequence was cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO cloning vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to yield entry vectors. The transfer of the Salicornia AChE from entry clone to pGWB2 was performed by an LR clonase reaction. The transgenic tobacco plants were generated by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of leaf discs.38 Regenerated transgenic tobacco plants were grown in a large growth cabinet (Koitotron type KG: Koito Ind., Ltd., Co., Tokyo, Japan) at 25°C under a 16 h light and 8 h dark cycle.

Crude extracts from leaves of transgenic tobacco plants were subjected to 12.5% SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins were electro blotted to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-rad Laboratories, Richmond, CA, USA). After blotting, the membrane was blocked with 10% (w/v) non-fat milk in TBST (10 mM Tris buffered saline (TBS) with 0.5% Tween 20) and incubated overnight with maize AChE polyclonal primary antibody raised in rabbit at 1:20 dilution and after washing further challenged with diluted (1:5,000) anti rabbit IgG-biotin conjugate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as secondary antibody for 2.5 h. After briefly being rinsed with 10 mM TBST and 10 mM TBS, an avidin-biotin-alkaline phosphatase (AP) complex reaction was performed, and then AP activity was visualized using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and nitro blue tetrazolium.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by “Ground-based Research Program for Space Utilization” promoted by Japan Space Forum. We thank Dr. Tsuyoshi Nakagawa (Shimane University) for providing us the destination vector, pGWB2.

Sequence data from this article have been deposited with the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession number AB489863.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- AChE

acetylcholinesterase

- ASCh

acetylthiocholine

- DTNB

5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Plant Signaling & Behavior E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/psb/article/8360

References

- 1.Momonoki YS, Oguri S, Kato S, Kamimura H. Studies on the mechanism of salt tolerance in Salicornia europaea L II. High osmosis of epidermal cells in stem. Jpn J Crop Sci. 1994;63:650–656. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimizu K, Ueda T. Seed dimorphism and factors influencing seed germination in Salicornia herbacea L. Jpn J Trop Agri. 1994;38:181–186. [In Japanese with English abstract.] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcum KB, Murdoch CL. Salt Glands in the Zoysieae. Ann Bot. 1990;66:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peacock CH, Dudeck AE. A comparative study of turfgrass physiological responses to salinity. In: Lemaire F, editor. Proc Fifth International Turfgrass Res Conf. Avignon: Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique; 1985. pp. 821–830. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flowers TJ. Physiology of halophytes. Plant and Soil. 1985;89:41–56. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torello WA, Rice LA. Effects of NaCl stress on proline and cation accumulation in salt sensitive and tolerant turfgrasses. Plant and Soil. 1986;93:241–247. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu L, Lin H. Salt tolerance and salt uptake in diploid and polyploid buffalograsses (Buchloë dactyloides) J Plant Nutr. 1994;17:1905–1928. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonard MK. Salinity tolerance of the turfgrass Paspalum vaginatum Swartz ‘Adalayd’: Mechanisms of growth responses. Ph.D. diss. Univ. of California: Riverside; 1983. (Diss. Abstr. AAC8405537) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorham J, Mcdonnell E, Jones RGW. Some mechanism of salt tolerance in crop plants. Plant and Soil. 1985;89:15–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenway H, Munns R. Mechanism of salt tolerance in non halophytes. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1980;31:149–190. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matoh T, Watanabe J, Takahashi E. Sodium, potassium, chloride and betaine concentration in isolated vacuoles of salt-grown Atriplex germini leaves. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:173–177. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moghaieb REA, Saneoka H, Fujiota K. Effect of salinity on osmotic adjustment, glycinebetaine accumulation and the betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase gene expression in two halophytic plants, Salicornia europaea and Suaeda maritime. Plant Sci. 2004;166:1345–1349. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Momonoki YS, Kamimura H. Studies on the mechanism of salt tolerance in Salicornia europaea L I. Changes in pH and osmotic pressure in Salicornia plants during the growth period. Jpn J Crop Sci. 1994;63:518–523. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Momonoki YS, Oguri S, Kato S, Kamimura H. Studies on the mechanism of salt tolerance in Salicornia europaea L III. Salt accumulation and ACh function. Jpn J Crop Sci. 1996;65:693–699. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly RB, Deutsch JW, Carlson SS, Wagner JA. Biochemistry of neuro-transmitter release. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1979;2:399–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.02.030179.002151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duant Y, Babel-Gurein E, Droz D. Calcium metabolism and acetylcholine release at the nerve-electroplaque junction. J physiol. 1980;76:471–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soreq H, Seidman S. Acetylcholinesterase—new roles for an old actor. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:294–302. doi: 10.1038/35067589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horiuchi Y, Kimura R, Kato N, Fujii T, Seki M, Endo T, et al. Evolutional study on acetylcholine expression. Life Sci. 2003;72:1745–1756. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wessler I, Kilbinger H, Bittinger F, Kirkpatrick CJ. The biological role of non-neuronal acetylcholine in plants and humans. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2001;85:2–10. doi: 10.1254/jjp.85.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans ML. Promotion of cell elongation in Avena coleoptiles by acetylcholine. Plant Physiol. 1972;50:414–416. doi: 10.1104/pp.50.3.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fluck RA, Jaffe MJ. Cholinesterase from plant tissues III. Distribution and subcellular localization in Phaseolus aureus Roxb. Plant Physiol. 1974;53:752–758. doi: 10.1104/pp.53.5.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fluck RA, Jaffe MJ. The distribution of cholinesterase in plants species. Phytochemistry. 1974;13:2475–2480. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartmann E, Kilbinger H. Occurrence of light-dependent acetylcholine concentration in higher plants. Experientia. 1974;30:1387–1388. doi: 10.1007/BF01919649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verbeek M, Vendrig JC. Are acetylcholine-like cotyledon-factors involved in the growth of the cucumber hypocotyls? Zeitschrift fuer Pflanzenphysiologie. 1977;83:335–340. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Momonoki YS, Momonoki T. Changes in acetylcholine levels following leaf wilting and leaf recovery by heat stress in plant cultivars. Jpn J Crop Sci. 1991;60:283–290. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roshchina VV. Neurotransmitters in plant life. Enfield: Science Publishers Inc.; 2001. pp. 99–150. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Momonoki YS. Occurrence of acetylcholine-hydrolyzing activity at the stele-cortex interface. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:130–133. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Momonoki YS. Asymmetric distribution of Acetylcholinesterase in gravistimulated Maize seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:47–53. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Upton C, Buckley JT. A new family of lipolytic enzymes? Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:178–179. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brick DJ, Brumlik MJ, Buckley JT, Cao JX, Davies PC, Misra S, et al. A new family of lipolytic plant enzymes with members in rice, Arabidopsis and maize. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:475–480. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akoh CC, Lee GC, Liaw YC, Huang TH, Shaw JF. GDSL family of serine esterases/lipases. Prog Lipid Res. 2004;43:534–552. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamoto K, Oguri S, Momonoki YS. Characterization of trimeric acetylcholinesterase from a legume plant, Macroptilium atropurpureum Urb. Planta. 2008;227:809–822. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0658-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sagane Y, Nakagawa T, Yamamoto K, Michikawa S, Oguri S, Momonoki YS. Molecular characterization of maize acetylcholinesterase. A novel enzyme family in the plant kingdom. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1359–1371. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.062927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, von Heijne G. A neural network method for identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Int J Neural Syst. 1997;8:581–599. doi: 10.1142/s0129065797000537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, Brunak S, Von Heijne G. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins based on their N-terminal amino acid sequence. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:1005–1016. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamamoto K, Momonoki YS. Subcellular localization of overexpressed maize AChE gene in rice plant. Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2008;3:576–577. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.8.5732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimose S, Takenaka F, Kimura O. Salt tolerance of glasswort, rush and goldenrod. Japan J Trop Agr. 1987;31:179–184. [In Japanese with English abstract.] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horsch RB, Fry JE, Hoffmann NL, Eichholtz D, Rogers SG, Farley RT. A simple and general method for transferring genes into plants. Science. 1985;227:1229–1231. doi: 10.1126/science.227.4691.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]