Abstract

Surgical simulation has evolved considerably over the past two decades and now plays a major role in training efforts designed to foster the acquisition of new skills and knowledge outside of the clinical environment. Numerous driving forces have fueled this fundamental change in educational methods, including concerns over patient safety and the need to maximize efficiency within the context of limited work hours and clinical exposure. The importance of simulation has been recognized by the major stake-holders in surgical education, and the Residency Review Committee has mandated that all programs implement skills training curricula in 2008. Numerous issues now face educators who must use these novel training methods. It is important that these individuals have a solid understanding of content, development, research, and implementation aspects regarding simulation. This paper highlights presentations about these topics from a panel of experts convened at the 2008 Academic Surgical Congress.

Keywords: Simulation, Surgical Education, Virtual Reality, Proficiency, Competency

INTRODUCTION

The training of surgeons is rooted in apprenticeship methods developed over a century ago, as originally championed by William Halsted in 1904. Until recently, immersion in the clinical environment with graduated levels of responsibility was the standard. Innovative educators, such as the group in Toronto, began to change this paradigm in the 1980’s with the introduction of bench stations designed to teach residents operative skills in a laboratory environment [1]. The advent of dramatic changes in surgical technology, as seen with the growth of laparoscopy in the 1990’s, forced surgeons to explore such alternatives to traditional educational models, largely in response to concerns over patient safety [2,3]. Importantly, research documented that simulators could effectively allow trainees to acquire new skills outside of the operating room.

The Residency Review Committee’s (RRC) introduction of the 80-hour work week in 2003 further augmented the surgical community’s interest in simulation as a means of more efficiently educating trainees given the requisite limits in clinical exposure. Meanwhile, major programs geared towards verifying competency were launched by both the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the American Board of Surgery. These initiatives catalyzed the need for establishing standards for education and more widely implementing novel training methods. Accordingly, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) established its program for the accreditation of Regional Education Institutes and the RRC mandated that all residencies implement skills lab curricula by 2008 [4,5]. Additionally, the Association of Program Directors in Surgery (APDS) in conjunction with the ACS established a National Skills Curriculum project [6]. Now, all of the major stake-holders in surgical education have endorsed the use of simulation in surgical education as a means of better ensuring competency [5].

Although much momentum has been gained in the field of surgical simulation, many educators have little experience in dealing with the various issues associated with these new training methods. Besides the obvious financial and logistical concerns of setting up a skills lab, understanding the development of simulation content, creating simulators, validity and reliability concepts, best educational methods, and using what’s currently available are just a few of the relevant aspects currently facing educators. The education committees of the Association for Academic Surgery and the Society of University Surgeons assembled a panel of experts to discuss the latter issues at the 2008 Academic Surgical Congress. This paper highlights each of these distinct but related facets of surgical education using a variety of technologies and strategies for simulation-based training.

STATE-OF-THE-ART VIRTUAL REALITY SIMULATOR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT

Current virtual reality (VR) simulators have been inspired by the need for repetition of selected tasks. Many centers have been able to document improvement in any of a number of particular activities using metrics like efficiency of motion, task completion time, and other psychomotor skills. Once a particular skill has been learned other exercises and additional modules must be developed for the learner by the simulator manufacturer. In all cases, the educator and the learner rely on the instrument manufacturer for the content and context of the exercise. Optimally, the educator would guide the development of the learning scenario and thus direct the cognitive content of the experience for the learner. For example, the surgical educator may choose to demonstrate an anatomic variant that is anticipated in an upcoming operation.

The University of Florida group has attempted to approach procedural simulation from a different perspective [7–9]. This group’s approach has been to develop a simulation platform that is driven by the teacher and the intended user. The Toolkit for Illustration of Procedures in Surgery (TIPS) places at the author’s disposition: 3D anatomic representation, instrument interfaces, force feedback, and various media like video-in-the-scene. An analogy may be that of word processing where the user defines the font, the spacing, and the particulars of the presentation a priori.

In the TIPS environment the teacher defines a task that he/she wishes to demonstrate. For example, consider the case of a right-sided adrenalectomy. The main issues to illustrate in this operation are: 1) identifying the location of the gland within the retroperitoneum, 2) identifying the junction of the adrenal vein and the vena cava, and 3) illustrating the critical steps of the dissection of the vein to prevent hemorrhage.

The system utilizes a computer with the addition of a haptic feedback device. The six-degree-of-freedom device called the Phantom-Omni © (SensAble Technologies; Woburn, MA) is utilized. This device can be modified to accommodate actual laparoscopic instrument handles which augment the reality of the experience [10]. The system interface is through a window that allows selection of the components that need to be demonstrated. In the current example, one would choose the adrenal gland, the kidney, the vena cava, and retroperitoneal fat. The structures can be modified with regard to color, deformability, size, etc. The structures are then placed together in the specific arrangement desired. To demonstrate anatomic variability one may choose to place one adrenal vein entering the vena cava and another entering the right renal vein directly. Fatty tissue can then be added to cover the anatomy.

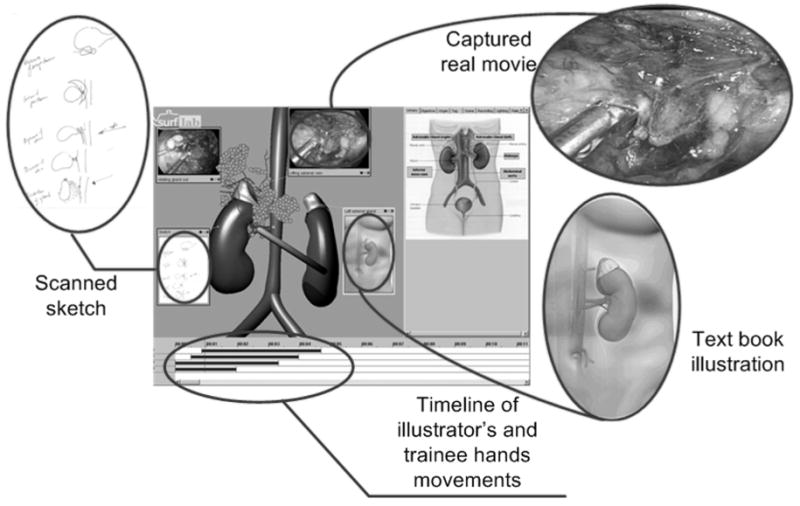

The dissection or exposure can be recorded using the haptic device. The dissection can then be illustrated through a number of mechanisms including actual operative images, hand-drawn diagrams, notes or pictures that can be placed along the dissection timeline (Fig. 1). Once this illustration phase is complete the “experience” can be turned over to the user.

Figure 1.

Example of adrenalectomy illustration in the TIPS environment: Any number of sources can be utilized to highlight the specific concept being demonstrated including drawings, operative videos, and the like.

The learner is then passively guided along the educator’s dissection path while holding the device handle. As the student follows the track, annotations become evident. For example, at the point of the junction of the right adrenal vein and the vena cava a warning that undue tension at this point will lead to hemorrhage that is difficult to control may appear; the learner will be simultaneously able to “feel” the tissue to further enhance the experience. A brief video of the dissection at that point can be displayed to advance the point.

In summary, an augmented illustrative tool for surgeons is being developed at the University of Florida. The number of possible anatomic constructs is limitless. The underlying architecture for the organs selected can be taken from actual computed tomographs of patients, thus reflecting the actual anatomy of the operation planned. The ability to construct the example and immediately allow the learner to utilize it is unique in the field of virtual reality.

TAKING INNOVATION TO THE MARKETPLACE AND NAVIGATING CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Faculty involved in educational innovation face several intellectual property decisions, such as: 1.) How do you decide to build a simulator? 2) How do you decide whether or not to file a patent? 3) How do you decide whether to enter into a license agreement versus starting your own company? In addition, issues relating to conflicts of interest in academia also arise.

How do you decide to build a simulator?

Needs assessments are a common and important factor when considering educational innovation [11]. Assessing both the program needs as well as the learners’ educational needs may reveal areas that can be addressed using simulation technology. In the event that commercially available technologies do not meet the above needs one may decide to build a simulator. In addition, research and personal interests may play a role when this decision. Research in simulation from a technology standpoint and educational perspective is on the rise and many simulation centers acquire or develop simulators for training purposes and research purposes. Modeling, motor learning, curriculum integration and performance quantification are some of the research areas of interest.

How do you decide whether or not to file a patent?

The desire to protect your intellectual property is a key factor in deciding whether or not to file a patent. Another major factor rests in the distribution plans for your technology. If you develop a computer based simulation and plan to share your technology via the internet, free of cost, then you may not want to incur the expense of filing a patent. However, if you are interested in working with an existing company to manufacture and distribute your technology you may have a better chance of obtaining a license agreement with a patented product. Moreover, if you plan to start a company based on your technology, your patent may prove to be a valuable asset.

How do you decide whether to enter into a license agreement versus starting your own company?

Entering a licensing agreement poses less financial risks; however you may significantly limit your own participation and profit margins. Some inventors choose to enter into a license agreement because their inventions require costly manufacturing and product support. Starting your own company requires time, money and knowledge of sales and marketing; however, there is the potential for greater profit margins.

Conflicts of Interest

Faculty members who desire or have intellectual property must familiarize themselves with institutional conflict of interest policies. Most universities reserve the right to claim ownership of an invention developed by their employees [12]. As a general rule, faculty and research staff are required, as a condition of their employment, to sign a patent agreement document assigning to the university their rights to patents, inventions and discoveries. In some instances the university may in turn assign rights to the inventor. Conflict of interest occurs when there is a divergence between a faculty member’s private interests and his/her professional obligations to the university. The most common situations in which conflicts of interest may arise include: 1) External financial interests, 2) Consulting commitments; 3) Use of students and support staff, and 4) Use of university resources. Most universities have their policies online and in the faculty handbook. Specific questions should be addressed to the institutions office of technology. In general, the most powerful tool in preventing conflict of interest is disclosure [13].

ASSURING COMPETENCY THROUGH SIMULATION: VALIDATION AND REAL WORLD USE OF TASK-BASED SKILLS TRAINING

Presently, the completion of surgical training is determined by elapsed time in training, general case volume standards, and relatively subjective end-of-rotation evaluations by faculty. While the ACGME has emphasized the use of reliable outcome measures for assessing the competence of resident physicians, these metrics are not yet well developed. In the field of Surgery, the explosion in technology and the development of minimally invasive techniques has provided both an impetus and an opportunity for developing innovative training programs. Specifically, simulation offers the promise of a safe, non-threatening training venue with the ability to objectively measure aspects of technical skills performance.

Laparoscopic surgery lends itself to simulation due to the relative ease of model development, however, these simulators must be rigorously evaluated and their metrics must demonstrate construct validity (e.g. the metric must accurately differentiate novice from expert performance) if simulator training is to be optimized. Therefore, prior to the development and implementation of our laparoscopic basic skills curriculum at the University of Michigan a series of studies were carried out to determine if the LapSim™ [14] and LapMentor™ [15] virtual reality simulators demonstrated construct validity, and whether training on the LapMentor™ simulator resulted in improved resident performance of basic laparoscopic skills in an animate operating room environment [16]. The LapSim™ simulator has been previously shown to demonstrate transferability of skills from the simulated to the applied environment [17], therefore this work was not repeated.

In these studies, the LapSim™ simulator was found to possess construct validity for at least one metric for each basic skills task evaluated [14], while the LapMentor™ metrics demonstrated only limited construct validity for its basic skills tasks [15]. Despite this limited construct validity, we did find that practice on the LapMentor™ simulator resulted in improved performance of basic skills in a porcine model [16]. These results were utilized to develop a proficiency-based laparoscopic basic skills curriculum, in conjunction with the work of Korndorffer and Scott who have established construct validity for a series of box trainer exercises (the “Southwestern stations”) [18] (Table 1). This curriculum was then evaluated in a randomized, controlled study designed to evaluate the impact of this proficiency-based curriculum on intra-operative performance. Briefly, control interns were randomized to open access to the simulation center without a specific curriculum prescribed, while the intervention group was required to achieve established expert level proficiency targets two consecutive times on a series of laparoscopic basic skills exercises (Table 1) prior to proceeding to the operating room for blinded assessment. Completion of this proficiency-based curriculum was found to result in improved intra-operative performance (unpublished data), with the box trainer exercises demonstrating a large effect size and the virtual reality simulator tasks demonstrating a more moderate effect size. Given these positive results, completion of this proficiency based curriculum is now required of all University of Michigan surgical interns prior to proceeding to the operating room for laparoscopic procedures.

Table 1.

University of Michigan Laparoscopic Basic Skills Curriculum

| Simulator | Task | Proficiency Target |

|---|---|---|

| Video Box Trainers [18] | Bean Drop | Total time – 24 seconds |

| Running String | Total time – 28 seconds | |

| Checkerboard | Total time – 68 seconds | |

| Block Move | Total time – 16 seconds | |

| Suture Foam | Total time – 17 seconds | |

|

| ||

| LapSim™ [14] | 0° Camera Navigation | Total time – 28 seconds |

| 30° Camera Navigation | Total time – 27 seconds | |

| Coordination | Total time – 33 seconds | |

| Instrument Navigation | Left Instr time – 9 seconds | |

| Grasping | Left Instr time – 37 seconds | |

| Lifting and Grasping | Total time – 44 seconds | |

| Clipping | Total time – 51 seconds | |

|

| ||

| * LapMentor™ [15] | 0° Camera Navigation | 10 repetitions |

| 30° Camera Navigation | 10 repetitions | |

| Eye Hand Coordination | 10 repetitions | |

| Translocation of Objects | 10 repetitions | |

| Clipping and Grasping | 10 repetitions | |

| Cutting | 10 repetitions | |

| Electrocautery | 10 repetitions | |

LapMentor™ proficiency targets were set at 10 repetitions due to the limited construct validity of the basic skills metrics.[15]

Looking ahead, the demand for objective demonstration of competence in surgical training will likely only increase. Experience with the development of proficiency-based curricula for laparoscopy, such as that utilized at the University of Michigan, should serve as a model for the development of proficiency-based curricula for other components of surgical training. This should then allow us to move towards a training paradigm where advancement is based upon demonstration of competence, as opposed to numbers of years or procedures completed.

ACS/APDS NATIONAL SKILLS CURRICULUM: ORCHESTRATING WIDE ADOPTION OF HIGH QUALITY, LOW COST PROGRAMS

The concept of deliberate practice has been defined by Ericsson as a well defined task with the appropriate difficultly level for the learner accompanied by informative feedback and opportunities for repetition and correction of errors [19]. This fundamental concept provides the underpinnings for the evolution of surgical skills laboratory into the mainstream of surgical residency training over the last ten years. A growing body of literature supports the transfer of skills learned in the laboratory to improve performance in the operating room with faster overall performance with fewer errors and greater economy of motion [20–22]. In an effort to establish surgical skills laboratory training on a firm educational foundation, a recent joint effort by the ACS and the APDS has initiated the development of a comprehensive surgical skills curriculum with the first of three phases made available on Moodle, a learning management system, in October of 2007. This first phase includes 20 basic surgical skills modules applicable to surgical trainees in all specialties. These modules cover basic surgical skills such as knot tying, suturing, airway management, chest tubes, central lines, as well as basic and advanced laparoscopic skills and vascular and gastrointestinal anastomosis. Phase II includes full operative procedures that either include a significant technical component or are rarely performed during residency training but considered vital for preparing the resident for surgical practice. These modules include procedures such as laparoscopic inguinal and ventral hernias, laparoscopic and open colon resections, thyroidectomy, parathyroidectomy, and procedures for peptic ulcer disease and gastric resection. This phase is to be available in early 2008. Phase III of the curriculum is focused on team-based training incorporating essential team-based skills such as communication, leadership, briefing and planning, resource management, seeking advice and feedback, coping with stress, decision making and global awareness. Table 2 identifies the training scenarios under development for this third phase of the curriculum to be released in the summer of 2008. These scenarios prepare the trainee to be a highly functioning member of the team in challenging scenarios on the surgical ward, the surgical intensive care unit, as well as the operating room and the post anesthesia recovery unit.

Table 2.

ACS/APDS Phase III Team Based Training Scenarios

|

PACU= post anesthesia care unit, OR= operating room, SICU= surgical intensive care unit

This new curriculum provides two alternatives for assessment of skills learned in the laboratory. The traditional Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) is one alternative as a multi-station exam with faculty observation of required tasks using checklist ratings. This methodology has often been viewed as faculty intense because of time required but does have the advantage of a proven track record of reliability. The newer methodology developed at Southern Illinois University is a set of eleven verification of proficiency modules. These modules provide for review of an expert performance of the skill with subsequent guided practice until the trainee is prepared to have the performance videotaped. The video is then reviewed by blinded expert faculty with either a “pass” or “needs more practice” rating specified; operating room performance is granted only after verification of proficiency.

The surgical skills laboratory is increasingly recognized as an ideal learning environment where learner goals take precedent over patient needs, where there is the opportunity for massed and deliberate practice without medical legal considerations, where it is possible to demonstrate errors and complications and where trainees can practice rare emergency procedures and new techniques. The ACS/APDS Skills Curriculum further enhances the remarkable potential of skills laboratories in surgical training programs throughout North America.

CONCLUSION

While educators now face many different issues regarding the use of simulation in surgical education, it is clear that various processes for training outside of the clinical environment are becoming well established. It is important for professionals involved in these activities to have a solid understanding of the issues related to creating simulations, performing simulation-based research, and using commercially available devices. Much needed work is continuing to evaluate validity and reliability, identify best training practices, and foster implementation of standardized curricula.

As our knowledge in this field expands, the use of well designed local and national simulation-based curricula will likely become increasingly widespread. Accordingly, trainees stand to reap the benefits in terms of skill and knowledge acquisition using increasingly effective and efficient methods. Given the utility of simulation as a means of ensuring proficiency, such methods will likely have a growing role in the context of competency-based guidelines for the advancement of trainees and the certification of practicing surgeons.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH-R21-EB005765-01A12 and the University of Florida College of Medicine Chapman Education Grants2

Footnotes

This work is a “Symposium” paper, highlighting presentations from the Committee on Education Session of the Association for Academic Surgery (AAS) and the Society of University Surgeons (SUS), scheduled on February 14, 2008 at the 2008 Academic Surgical Congress (ASC), Huntington Beach, CA.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wanzel KR, Ward M, Reznick RK. Teaching the surgical craft, from selection to certification. Curr Probl Surg. 2002;39:573. doi: 10.1067/mog.2002.123481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore MJ, Bennett CL. The learning curve for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The Southern Surgeons. Club Am J Surg. 1995;170:55. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott DJ. Patient safety, competency, and the future of surgical simulation. Simul Healthcare. 2006;1:164. doi: 10.1097/01.sih.0000244453.20671.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Surgeons (ACS) Program for the Accreditation of Education Institutes. http://www.facs.org/education/accreditationprogram/index.html

- 5.Bell RH. Surgical Council on Resident Education: A new organization devoted to graduate surgical education. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:346. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott DJ, Dunnington GL. The new ACS/APDS skills curriculum: moving the learning curve out of the operating room. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0357-y. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim M, Ni T, Cendán JC, Kurenov S, Peters J. A Haptic-enabled toolkit for illustration of procedures in surgery (TIPS) Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;125:209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cendán JC, Kim M, Kurenov S, Peters J. Developing a multimedia environment for customized teaching of an adrenalectomy. Surgical Endoscopy. 2007;21:1012. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim M, Punak S, Cendán JC, Kurenov S, Peters J. Exploiting graphics hardware for haptic authoring. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2006;119:255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurenov SN, Punak S, Kim M, Peters J, Cendan JC. Simulation for training with the Autosuture Endostich Device. Surg Innov. 2006;13:283. doi: 10.1177/1553350606296923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pugh CM, DaRosa DA, Glenn D, Bell RH., Jr A comparison of faculty and resident perception of resident learning needs in the operating room. J Surg Educ. 2007;64:250. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metlay G. Reconsidering Renormalization: Stability and Change in 20th-Century Views on University Patents. Soc Stud Sci. 2006;3:565. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd EA, Bero LA. Assessing faculty financial relationships with industry. A case study. JAMA. 2000;284:2209. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.17.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodrum DT, Andreatta PB, Yellamanchili RK, Feryus L, Gauger PG, Minter RM. Construct validity of the LapSimTM laparoscopic surgical simulator. Am J Surg. 2006;191:28. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andreatta PB, Woodrum DT, Yellamanchili RK, Gauger PG, Minter RM. LapMentor™ metrics possess limited construct validity. Simulation in Healthcare. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e31816366b9. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andreatta PB, Woodrum DT, Birkmeyer JD, Yellamanchili RK, Doherty GM, Gauger PG, Minter RM. Laparoscopic skills are improved with LapMentor™ training: results of a randomized, double-blinded study. Ann Surg. 2006;243:854. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000219641.79092.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyltander A, Liljegren E, Rhodin PH, Lonroth H. The transfer of basic skills learned in a laparoscopic simulator to the operating room. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1324. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-9184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korndorffer JK, Scott DJ, Sierra R, et al. Developing and testing competency levels for laparoscopic skills training. Arch Surg. 2005;140:80. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ericsson KA, Krampe RT, Tesch-Romer C. Psychological Review. 1993;100:363. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seymour NE, Gallagher AG, Roman SA, et al. Virtual reality training improves operating room performance. Ann Surg. 2002;236:458. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grantcharov TP, Kristiansen VB, Bendix J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of virtual reality simulation for laparoscopic skills training. Br J Surg. 2004;91:146. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haque S, Srinivasan S. A meta-analysis of the training effectiveness of virtual reality surgical simulators. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2006;10:51. doi: 10.1109/titb.2005.855529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]