Abstract

Single molecule experiments that can track individual trajectories of biomolecular processes provide a challenge for understanding how these stochastic trajectories relate to the global energy landscape. Using trajectories from a native structure based simulation, we use order parameters that accurately distinguish between protein folding mechanisms that involve a simple, single set of pathways versus a complex one with multiple sets of competing pathways. We show how the folding dynamics can be analyzed with replica correlation functions in a way compatible with single molecule experiments.

Keywords: single molecules, protein folding, replica correlation functions

It is now well established that proteins fold via an ensemble of states in which the energy landscape is globally funneled or directed towards a structurally well-defined native state [1, 2, 3, 4]. At the level of individual trajectories of protein folding, one can envisage multiple pathways from the denatured ensemble descending down a funneled energy landscape until they join up as they approach the native state. For proteins in the laboratory the nature of the discrete trajectories of protein molecules and the degree of similarity of one path of approach to another as the molecule goes to the folded state is still an open question.

Extraordinary progress has been made in the past few years in the development of experimental methods sensitive enough to study the dynamical properties of single molecules [5]. It is now possible to follow, in part, the trajectories of individual molecules to track the dynamical time-dependence of features of their conformation in space [6, 7, 8, 9]. The random sequence of events during transitions of the folding of proteins and other biomolecules at the individual molecular level, intrinsically gives stochastic data. As such, statistical physics tools are needed to quantify the pathways traversed in a set of individual trajectories and map the statistical properties of such single molecule data to the topography of the energy landscape [10].

In this paper, we demonstrate that statistical physical tools can richly quantify, in principle, the pathways from a collection of trajectories. Specifically, using trajectories from simulations of proteins from perfectly funneled energy landscapes, we show that appropriately computed replica correlation functions can diagnose whether folding occurs largely via a single set of pathways or whether several distinct sets of competing routes to the native state actually coexist. This is the first application of replica correlation functions to a concrete problem after their introduction in the context of protein folding in Ref. [11].

Ordinarily, partially folded protein conformations in simulations are characterized with the help of appropriately chosen order parameters measuring the similarity to the final native structure. On the other hand, replica order parameters measure the similarity between the different routes taken to the final product. To define such a quantity a measure in phase space is required to quantify how similar two microscopically distinct configurations are to each other. For proteins and random polymers, the overlaps function between two conformations is a useful object because it correlates with pair interaction energies. The overlap between conformation i and j is then an explicit function qij = Φ({r(i)}, {r(j)}) of the atomic coordinates {r(i)} and {r(j)}. On a somewhat coarse grained scale, an appropriate choice for the function Φ is the fraction of contacts between specific residues in the macromolecule which occur in both configurations. When one of the configurations is the native state (with atomic coordinates {r(f)}) then Qi = Φ({r(i)}, {r(f)}) is simply the fraction of native-like tertiary contacts of conformation i.

This global quantity qij determines the overall shape similarity, but would be difficult to directly measure. Experimentally, the corresponding pair specific quantity is accessible by means of fluorescence quenching studies. If residue m contains an energy donor which can be excited, while residue n has a chromophore to act as an energy acceptor, then the time-dependence of the mn contact can be experimentally resolved. If this contact is made in configuration i and in configuration j of another trajectory then . The global overlap is then given by the sum over all possible contacts, i.e. .

With this reaction coordinate the replica correlation function between two paths α and β (which both fold into the native state) can be defined as [11]

| (1) |

where 〈…〉 denotes an ensemble average, θ(x) is Heaviside’s function, tp and tl are the preparation time (i.e., the time elapsed before the observation is started) and lookback time, respectively, Nt is the value of the reaction coordinate at the transition state, and jα(t) and jβ(t) are the (normalized) flux in trajectory α and β into the product state at time t. Generally, special care is required in choosing the adequate reaction coordinate and associated transition state. However, for the purpose of this study it is sufficient to simply choose the transition state in such a way that once the system leaves the transition state (in direction of the product) it is committed to react. Quantities similar to these replica correlation functions have been studied in the theory of disordered systems such as glasses and spin glasses [12, 13, 14, 15, 16]

The replica correlation provides a measure of how similar two trajectories are to each other at all times. However, to compare trajectories, one has to take into account that different trajectories traversing the same route might spend different amount of times in the vicinity of a given region in phase space such as, e.g., the transition state. Even if the two trajectories lead to the folded state via the same intermediate conformations, this sequence of events takes different amounts of time. The Laplace transform provides a natural means of comparing trajectories of different duration, and we use it here to quantify the similarity of our molecular trajectories. This general analysis reveals, in particular, the near equilibrium behavior (for s → 0) and fast motions (s → ∞).

The simulation data were obtained from a Cα native topology-based model, which is described in detail in Ref. [17]. Briefly, a single bead centered on the Cα position represents a residue and bond and angle potentials string together the beads to their neighbors along the protein chain. The dihedral potential encodes the secondary structures. The protein’s native topology defines the network of favorable long-range tertiary interactions, while all other non-bonded interactions are repulsive.

The network of native contact pairs was determined using the CSU (Contacts of Structural Units) software [18]. Multiple trajectories with numerous unfolding/folding transitions were collected and analyzed using the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) to calculate the free energy surface projected onto the fraction of native contacts Q (defined as in Ref. [19]). The folding temperature (Tf) was identified as the peak of a specific heat versus temperature profile.

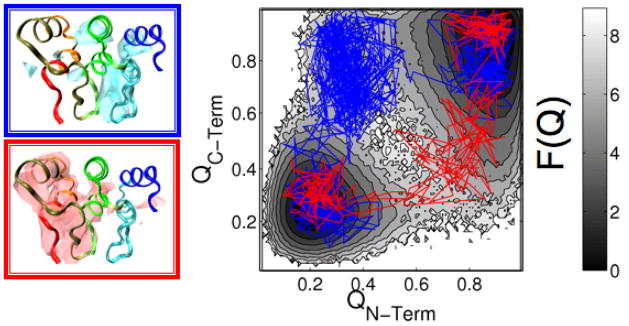

To analyze the transitions between the unfolded and folded states, we performed multiple constant temperature simulations (T = Tf) of the src-SH3 protein and the designed ankyrin repeat protein (PDB Code: 1SRL and 1N0Q, respectively). Each constant temperature trajectory consists of multiple transitions between the unfolded and folded ensembles. The trajectories were then combined to calculate the free energy profiles with respect to Q (see Fig. 1 as an example for 1N0Q).

Figure 1.

Protein folding with multiple sets of pathways. (left) A ribbon diagram is shown of 1N0Q with clouds representing the folded ensemble of the pathway where the c-terminal (top) or n-terminal (bottom) folds first. (right) A free energy profile is projected to the fraction of native contacts of the n-terminal [Q(n-term)] and the c-terminal [Q(c-term)] with two example trajectories overlaid.

From long trajectories, we extracted for further analysis only those portions where the transitions between the unfolded and folded states occurred. The unfolded and folded states were chosen as the values of Q at which the free energy is 1 kBT above the appropriate free energy minimum. The Q values that demarcate the unfolded and folded ensembles for 1SRL are 0.26 and 0.81, respectively, while for 1N0Q the values are 0.15 and 0.81. 399 trajectories for 1SRL which went through 40790 different conformations and 126 trajectories for 1N0Q with 51570 different conformations were used for analysis.

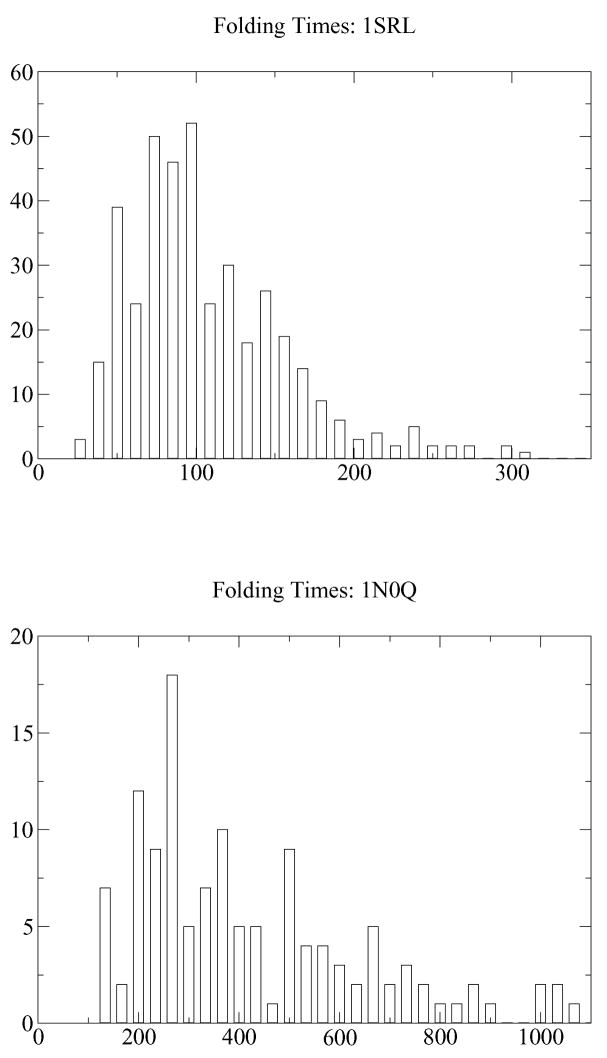

Previous studies indicate that 1SRL predominantly folds via a single correlated route, while 1N0Q, clearly possesses distinct sets of competing folding pathways [19]. One clear difference between these systems is the distribution of the folding times (i.e., number of steps required to reach the folded state for the first time starting from the unfolded one). These are shown in Fig. 2. While the distribution for 1SRL is unimodal, the one for 1N0Q is wide and skewed, consistent with two peaks (as expected for 1N0Q which has at least two different folding pathways with different folding times).

Figure 2.

Histogram of folding times for 1SRL (top) and 1N0Q (bottom).

A protein with several distinct sets of folding pathways should encounter a more diverse ensemble of conformations along its folding trajectory. To see this, we have discretized the set of folding trajectories and analyzed the distribution of qij (defined as in Ref. [19]) for all states i and j which have a given Q (and thus a given similarity with the folded state) for different Q. In doing so, we projected all of the conformations onto N = 30 different states where state i (with 1 ≤ i ≤30) represents all microscopic conformations having Q between i/N and (i + 1)/N. A complete folding trajectory is a sequence of microscopic conformations {r(t)}, but in this discretization scheme it becomes a sequence {ρ(t)} of integers. A coarse-grained folding pathway is a sequence of transitions between the N = 30 different discrete states starting at the unfolded state (ρ(t = 0) = 1) and ending in the native state (ρ(t = tf) = N).

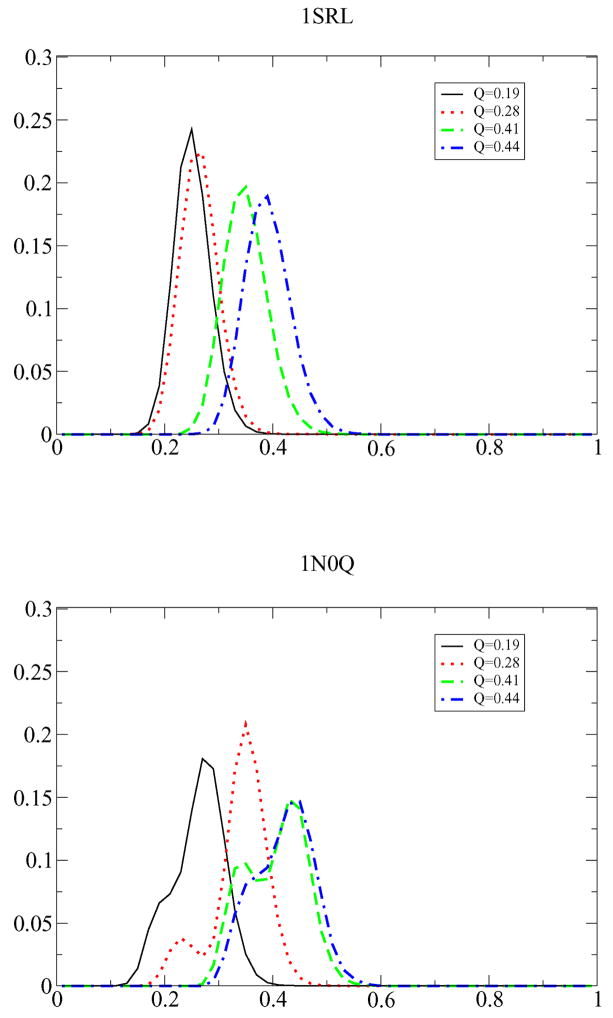

The comparison of all NQ conformations having a given Q requires numerical operations. We therefore restricted the analysis to a subset of the 1N0Q trajectories. Fig. 3 shows the distribution of q for 4 different Q values for all 399 1SRL trajectories and 34 randomly picked 1N0Q-trajectories (out of the total 126 trajectories). Generally, we find that the distribution of q is unimodal for 1SRL for all Q, indicating that the conformations of the folding pathways are very similar. For 1N0Q however, the distribution of relative q is distinctly bimodal for the range 0.24 ≤ Q ≤ 0.44.

Figure 3.

The distribution of q as function of Q. Data shown are for bins of width 0.02 (continuously interpolated) centered around Q =0.19, 0.28, 0.41, 0.44 for 1SRL (top) and for 1N0Q (bottom). For 1N0Q the distribution starts to be bimodal around Q = 0.24 (data not shown). For Q > 0.44 the distribution becomes unimodal. The q-distribution of 1SRL is unimodal for all 0.26 < Q < 0.81.

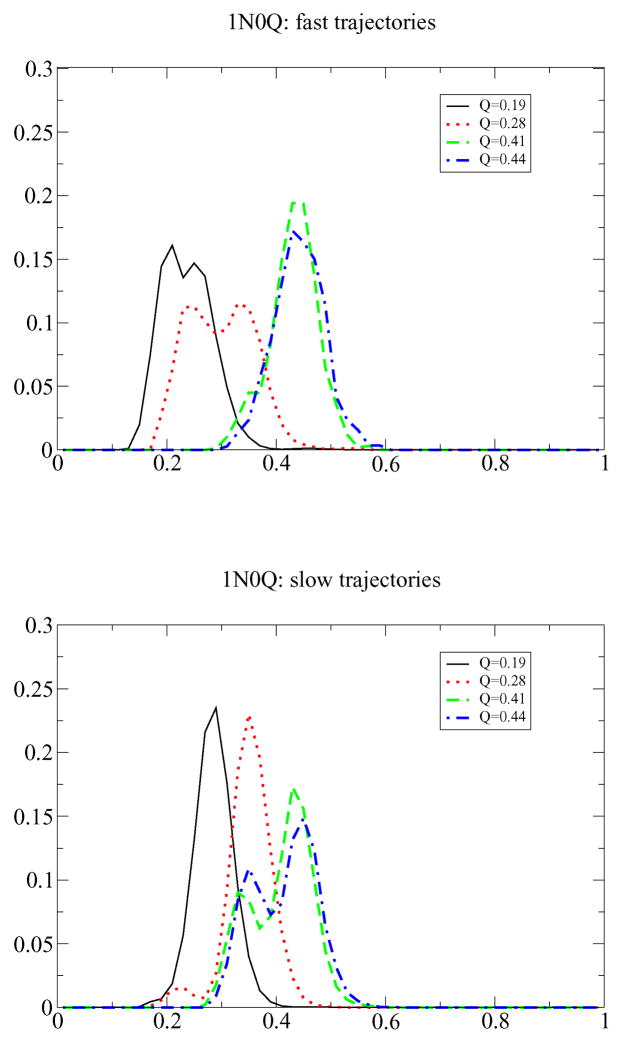

To check how folding times influence the q-distribution, we can partition the folding trajectories into slow, medium, and fast folding pathways1. As shown in Fig. 4, for the fast trajectories the bimodality is more pronounced at smaller Q (Q ≃ 0.28), while for slower trajectories the q-distribution becomes bimodal only at larger Q (Q ≃ 0.44). All of the 1SRL trajectories (slow, fast and medium) are unimodal (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Distribution of q for given Q for 1N0Q. Data are shown for fast trajectories (top) and slow trajectories (bottom). Fast trajectories find the folded states within 330 steps, slow ones need more the 660 steps. As one sees the q-distribution is sharper for the fast trajectories.

The bimodality of the q-distribution implies that the two subsets of the protein conformations have very few common structural features. In the context of protein folding, the key event leading to the bifurcation into the 2 subsets occurs upon reaching the transition state ensemble. Thus, in Fig. 3 those conformations that have reached the transition state have large structural differences from those which haven’t yet reached the transition state, leading to the small q-values. The unimodal distribution for 1SRL and the bimodal distribution for 1N0Q agree with our expectations from their distinct pathways patterns. For 1N0Q, the fast and slow trajectories take different routes in configuration space. For the fast trajectories the transition state is reached for small Q (Q ≃ 0.28), while the slow trajectories reach the transition state only for larger Q (Q ≃ 0.44). Thus, the transition state is reached by conformations with significant structural differences implying that (at least) 2 different transition states exist that lead to different folding times.

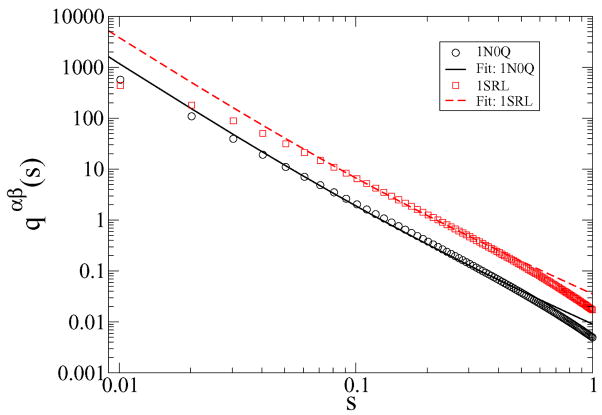

As in the earlier analysis of pathways on random landscapes, we analyze the Laplace-transform of the replica correlation function [11]. The numerically calculated Laplace-transform qαβ of Eq. (1) is shown in Fig. 5 as function of the single Laplace variable s associated with the lookback time (for tl1 = tl2). The Laplace variables sp1 and sp2 associated with the preparation times can be set to zero since our trajectories are well equilibrated. As shown in Fig. 5, for small s (0 < s < 1) qαβ decays algebraically for both 1SRL and 1N0Q. For larger s > 1, qαβ(s) decays exponentially (data not shown) as one expects for a set of data with discrete time steps (with the dominant contribution coming from the correlations between nearly denaturated states). Note, qαβ(s) is generally larger for 1SRL than for 1N0Q reflecting the fact that the conformations encountered during folding are generally more similar for 1SRL than for 1N0Q.

Figure 5.

The Laplace transform of the replica correlation function qαβ(s) for 1N0Q (solid black) and 1SRL (dashed red) as determined numerically from the simulation data (time unit=1 simulation step).

This characteristic s-dependence reflects the full dynamics of the folding transition (from the transition state ensemble to the native state). To illustrate this connection we now consider a simple protein folding model that describes the folding transition as a simple sequence of reactions between well-separated states. More specifically, we generalize the model introduced in Ref. [11] to a system with 2 different ensembles of transition states. The states of the reactant ensemble ΩD reach the transition states with energy Ei,α of ensemble α (α = 1, 2) with rates kd,α, the reverse reaction has a rate k0,αeβEi,α, while the transition from ensemble α to the folded state occurs with rate κF,α. Interconversion between the states of ensemble α occurs with rate , where is the number of states in ensemble α.

The occupation probabilities PD (of the reactant states) and Pl,α (of transition state l of ensemble α) can be explicitly calculated

| (2) |

| (3) |

where the Laplace transformed quantities are denoted by P̃. Furthermore, with s̃ = s + κF,α

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

The Laplace transformed replica correlation function becomes

| (7) |

where is the (Laplace-transformed) occupation of state k in transition state ensemble α assuming that at tl = 0 only state i is populated and is the occupation of state i of transition state ensemble α assuming that at tp = 0 only the reactant ensemble is populated.

If the internal relaxation in the transition state ensembles can be neglected (ω0,α = 0), then (in leading order)

| (8) |

while for a system with forward reaction only (k0,α = 0)

| (9) |

With the last 2 formulas, it is not possible to fit the numerical data of Fig. 5, which decays as qαβ ~ s−2.5 (data not shown). In Eqs. (8) and (9) the decay of qαβ with s is too slow and reasonable fits require that either ωi,α < 0 or κF,α < 0 (data not shown). The characteristic s-dependence of qαβ can only be explained if higher order corrections are taken into account in Eq. (8).

The data can be interpreted more directly by taking the dynamics of the folding transition explicitly into account. For this purpose, it is sufficient to describe the folding transition as a 1-dimensional diffusion process in a potential. To keep the analysis analytically tractable we focus here on a linear potential.

Here, the transition state is assumed to be at x = 0, the folded state at xf > 0 (which is in accordance with our above choice of the transition state). In the presence of a linear potential V (x) the probability distribution P(x, t) obeys the Fokker-Planck equation

| (10) |

where V′(x) = ∂x V (x) = −kBT/a. Upon Laplace-transforming P (x, t) one has for the initial condition P(x, 0) = δ(x − x0) for xf > x0 ≥0

| (11) |

One can easily show that this equation has the solution

| (12) |

where and τ = a2/D. With , one then obtains in leading order for the replica correlation function

| (13) |

with a constant C and τ̃ = τxf/a. The fit in Fig. 5 corresponds to τ̃−1 = 0.13 (1N0Q) and τ̃−1 = 0.11 (1SRL), which in turn corresponds to energy differences ΔF ≃ 7.7kBT and ΔF ≃ 8.9kBT between the transition state and the folded state. For 1N0Q this compares well with ΔF ≃ 7kBT from the simulations, while for 1SRL the estimate for the barrier is off by a factor of 2 (simulations: ΔF ≃ 4kBT). This implies that the description of the folding dynamics as diffusion in a linear potential works better for 1N0Q than for 1SRL.

In this study, we have sought to demonstrate how static and dynamic replica correction functions can be used to analyze single molecule experiments. These tools allow one to characterize quantitatively how large the accessed phase space is during a complex reaction. The s-dependence of the Laplace transformed replica correlation function q(s) provides information about the multiplicity of routes taken to the folded state.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for helpful discussions with Koby Levy. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 5R01 GM44557 and the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics through National Science Foundation Grants PHY0216576 and PHY0225630. S.S.C. is supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award from the National Institutes of Health. P.L. is supported by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

Footnotes

PACS: 82.37.Np, 87.15.Cc, 87.15.hm

For 1N0Q (1SRL), fast trajectories find the folded states within 330 steps (100 steps) and slow ones need more than 660 steps (200 steps).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:70. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliveberg M, Wolynes PG. Q Rev Biophys. 2005;38:245. doi: 10.1017/S0033583506004185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolynes PG, Onuchic JN, Thirumalai D. Science. 1995;267:1619. doi: 10.1126/science.7886447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Socci ND, Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Proteins. 1998;32:136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu HP, Xu L, Xie XS. Science. 1998;282:1. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Florin EL, Moy VT, Gaub HE. Science. 1994;264:415. doi: 10.1126/science.8153628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith SB, Cui YJ, Bustamante C. Science. 1996;271:795. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuler B, Eaton WA. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:16. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel A, Müller DJ. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:715. doi: 10.1038/78929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hummer G, Szabo A. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071034098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onuchic JN, Wang J, Wolynes PG. Chem Phys. 1999;247:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cugliandolo LF, Kurchan J. Phys Rev Lett. 1993;71:173. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mezard M, Parisi E, Virasaro MA. Spin glass theory and beyond. World Scientific Press; Singapore: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouchaud JP. J Physique I. 1992;2:1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monthus C, Bouchaud JP. J Phys A. 1996;29:3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sompolinsky H, Zippelius A. Phys Rev Lett. 1981;47:359. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clementi C, Nymeyer H, Onuchic JN. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:937–953. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobolev V, Sorokine A, Prilusky J, Abola EE, Edelman M. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:327–332. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho SS, Levy Y, Wolynes PG. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:586–591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509768103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nymeyer H, Socci ND, Onuchic JN. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]