Abstract

In this study, we evaluated the effects of Panax notoginseng root extract (NGRE) and its major constituents on SW480 human colorectal cancer cells. We used high performance liquid chromatography to determine the contents of major saponins in NGRE. The anti-proliferative effects were evaluated by the cell counting method, and concentration-related anti-proliferative effects were observed. At 1.0 mg/ml, NGRE inhibited cell growth by 85.8% (P<0.01), probably linked to the higher concentration of ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1. The pharmacologic activities of notoginsenoside R1 and ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1 on the cells were antiproliferative. We tested the effects of NGRE on DNA synthesis by measuring [3H]-thymidine incorporation. NGRE induced cell apoptosis at 0.5 and 1 mg/ml. Two-day treatment with 300 μM of notoginsenoside R1, ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1 increased cell apoptosis significantly. Cell cycle and cyclin A assay showed that NGRE arrested cells in the synthesis phase and increased the expression of cyclin A remarkably. NGRE also enhanced the actions of two chemotherapeutic agents, 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan. Cell growth decreased more with the combined treatment of NGRE and 5-fluorouracil (or irinotecan) than with the chemotherapy agent applied alone, suggesting that notoginseng can reduce the dose of 5-fluorouracil (or irinotecan) needed to achieve desired effects. Further in vivo and human trials are warranted to test whether notoginseng is a valuable chemo-adjuvant with clinical validity.

Keywords: Panax notoginseng, notoginseng saponins, SW480 human colorectal cancer cells, anti-proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle, 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common malignancies in the West and ranks as the second cause of cancer death in both men and women worldwide (1). Although early stage colorectal cancer can be cured by surgical resection, surgery is often combined with adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy with one or more chemotherapeutic agents. Even with effective strategies that continue to be developed for treating colorectal cancer, chemotherapy has the drawbacks of severe adverse effects and dose-limiting toxicity. Drug-related adverse events not only worsen patients' quality of life, but also can lead to their refusal to continue chemotherapy (2-4). Chemotherapy-induced toxicity can be reduced by chemo-adjuvant compounds that potentiate tumoricidal effects with smaller doses. Identifying non-toxic chemo-adjuvants among herbal medicines may be an essential step in advancing the treatment of the cancer (5).

Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F.H. Chen is cultivated throughout Southwest China, Burma, and Nepal. The root, the commonly used part of this plant called notoginseng or sanchi, has a long history as a remedy in Oriental traditional medicine (6,7). Notoginseng reportedly exerts beneficial effects in treating trauma and bleeding from internal or external injury, promoting blood circulation, reducing blood clotting, and alleviating pain, especially cancer pain (8). The main constituents in notoginseng are saponins, which are responsible for the herb's multifaceted pharmacological activities (6,7). To date, over 50 different saponins, including ginsenosides, notoginsenosides, and gypenosides, have been identified in notoginseng. Ginsenosides Rg1, Rb1, Rd, and notoginsenoside R1 are considered its major components (7).

Cancer treatment with botanicals like notoginseng has received increasing attention in the past decade (7,9). The effects of notoginseng on colorectal cancer have not been tested. The mechanism of the anti-proliferative activities of notoginseng is not clear and there are few studies of the mechanisms of notoginseng in cancer (10). In this study, we determined the content of the major saponins in notoginseng root extract using high performance liquid chromatography. Then, we investigated the effect of notoginseng extract on SW480 human colorectal cancer cells. Using flow cytometry, we assayed the effect on cell apoptosis, the cell cycle, and the expression of cyclin A in SW480 cells. Finally, we evaluated the activity of notoginseng on chemotherapeutic agents preliminary step in the development of an effective chemo-adjuvant for colorectal cancer treatment.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and preparation of notoginseng extract

The chemical composition of notoginseng differs according to its origin. We selected notoginseng cultivated in Wenshan for our study since its quality has been controlled under Good Agricultural Practice criteria (11), and it has been used in many previous studies (12,13). The notoginseng root sample obtained from the Yunnan Chinese Herbal Medicine Company was collected in 2004 and was authenticated by the Department of Pharmacognosy, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing. The sample was identified by macro-morphological and microscopic characteristics and thin layer chromatography (TLC). Based on the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, it was identified as the root of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) F.H. Chen.

The notoginseng root was ground to powder and passed through a 40 mesh sieve. Approximately 25 g of the powder was extracted with 500 ml 75% ethanol for 4 h. When the solution was cooled, it was filtered with P8 filter paper (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) to collect the filtrate. The residue was extracted with 500 ml 75% ethanol once more and then filtered while the solution cooled. The filtrate was mixed and the solvent was evaporated under vacuum. The dried extract was dissolved in 100 ml water and then extracted with water-saturated n-butanol. The n-butanol phase was evaporated under vacuum before the extract was lyophilized. The notoginseng root extract (NGRE) was stored at -20°C before use (14).

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis

The HPLC system was a Waters 2960 instrument (Milford, MA) with a quaternary pump, automatic injector, a photodiode array detector (Model 996), and Waters Millennium software for peak identification and integration. The separation was carried out on an Alltech Ultrasphere C18 column (5 μ, 250×3.2 mm I.D.) (Deerfield, IL) with a Alltech Ultrasphere C18 guard column (5 μ, 7.5×3.2 mm I.D.). For HPLC analysis, a 20-μl sample was injected into the column and eluted at room temperature with a constant flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. Acetonitrile (solvent A) and water (solvent B) were used in the mobile phase. Gradient elution proceeded as follows: started with 17.5% solvent A and 82.5% solvent B; changed to 21% A for 20 min; changed to 26% A for 3 min; held for 19 min; changed to 36% A for 13 min; changed to 50% A for 9 min; changed to 95% A for 2 min; held for 3 min; changed to 17.5% A for 3 min; held for 8 min. The detection wavelength was set to 202 nm. Ginsenosides and notoginsenoside standards and NGRE were dissolved in methanol. All solutions were filtered through Millex 0.2-μm nylon membrane syringe filters (Millipore Co., Bedford, MA) before use (15).

Cell culture

SW480 human colorectal cancer cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were routinely maintained in Leibovitz's L-15 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin (50 U/ml) (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Cancer cells were grown in a tissue culture dish (100 mm in diameter) and kept in a humidified incubator (5% CO2 at 37°C) with a medium change every 2-3 days. When the cells reached >80% confluence, they were trypsinized, harvested, and seeded into a new tissue culture dish.

Cell proliferative assay

The SW480 cell proliferative assay was performed as previously described (16). Briefly, cell viability was measured after 72 h of incubation with test extract/compound at various concentrations. Ethanol concentrations in all cell culture experiments did not exceed 1%. Control cultures were incubated in medium containing vehicle alone. On selected days, the cell monolayer was washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Cultures were harvested and monitored for number by using a Coulter cell counter (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL). The cell proliferative assay was performed at least three times. The percentage of proliferation was calculated as follows: Cell proliferation (%) = (cell number in each experimental well ÷ average of cell number in all control wells) × 100.

Morphological observation by staining with crystal violet

Morphological changes of SW480 cells were observed by crystal violet staining assay. After SW480 cells were seeded in 24-well plates for 24 h, NGRE at various concentrations was added to the medium and plates were incubated for 72 h. Then the medium was discarded and adherent cells were washed with PBS, stained and fixed with 0.2% crystal violet in 10% phosphate-buffered formaldehyde for 2 min. The crystal violet solution was then discarded and cells were washed gently with water. Adherent cells were observed and photographed under a microscope (Nikon, Eclipse, TE2000-U, Japan).

[3H]-thymidine incorporation assay

The [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay was performed after the cells were treated with NGRE and ginsenoside Rb1 (17). As described above, SW480 cells were seeded in a 24-well plate where they adhered for 24 h. The cells were incubated with test extract/compound at various concentrations and 300 μl of media containing 1 λ/ml [3H]-thymidine in each well for 72 h (the controls were incubated in normal medium alone). After washing cells with PBS and 10% trichloroacetic acid, 0.5 ml of 0.2 M NaOH was added into each well and agitated for 5 min. Finally, the cells with solution were transferred into vials; 30% liquid scintillation of 5 ml was added, and radioactivity counts were measured using a liquid scintillation analyzer (Tri-Carb 1500, Packard, Ramsey, MN). Results are presented as the percentage of control values.

Apoptosis assay after staining by annexin V/propidium iodide

SW480 cells were seeded in 24-well tissue culture plates (1×105). After 1 day, the medium was changed and NGRE, notoginsenoside R1, and ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1 were added. After treatment for 24, 48 and 72 h, cells floating in the medium were collected. The adherent cells were detached with 0.05% trypsin. Then culture medium containing 10% FBS (and floating cells) was added to inactivate trypsin. After being pipetted gently, the cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 1500 g. The supernatant was removed and cells were stained with annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide according to the manufacturer's instructions. Untreated cells were used as control for double staining. The cells were analyzed immediately after staining using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) and FlowJo 7.1.0 software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). For each measurement, at least 20,000 cells were counted.

Cell cycle and cyclin A assay using flow cytometry

SW480 cells were seeded in 24-well tissue culture plates (1×105). On the second day, the medium was changed, and cells were treated with NGRE at a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. Cells were incubated for 24, 48, and 72 h before harvesting. The cells were fixed gently by adding 80% ethanol and placing them in a freezer for 2 h. They were then treated with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 5 min in an ice bath. The cells were resuspended in 300 μl of PBS containing 40 μg/ml propidium iodide and 0.1 mg/ml RNase. Then, 20 μl of cyclin A-FITC was added to the cell suspension. Untreated SW480 cells were stained with the isotype control antibody as well. Cells were incubated in a dark room for 20 min at room temperature and analyzed with a FACScan flow cytometer. The cells were then subjected to cell cycle and cyclin A analysis.

Chemicals

HPLC grade methanol, n-butanol, acetonitrile, and ethanol were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Mili Q water was supplied by a water purification system (U.S. Filter, Palm Desert, CA). Ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, Rd, Re, Rg1, Rg2, Rh1 and notoginsenoside R1 were obtained from the Delta Information Center for Natural Organic Compounds (Xuancheng, P.R. China). 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was obtained from American Pharmaceutical Partners Inc. (Schaumburg, IL). Irinotecan, doxorubincin, ethanol, formaldehyde, NP40, crystal violet, propidium iodide (PI) and RNase were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). An annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit and FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibody to cyclin A and isotype control were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA).

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Data were analyzed using Student's t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures. The level of statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

HPLC analysis of NGRE

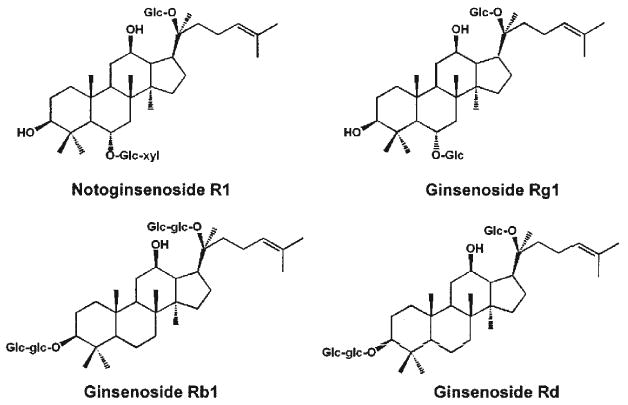

The chemical structures of 4 saponins are shown in Fig. 1. Saponins in notoginseng root extract were identified by observing the retention times and UV spectrum of authentic ginsenoside Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, Rd, Re, Rg1, Rg2, Rh1, and notoginsenoside R1 standards obtained from the mixed standards chromatograms. Fig. 2A shows representative HPLC chromatograms of NGRE.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of four major saponins in notoginseng: notoginsenoside R1 and ginsenosides Rg1, Rb1, and Rd.

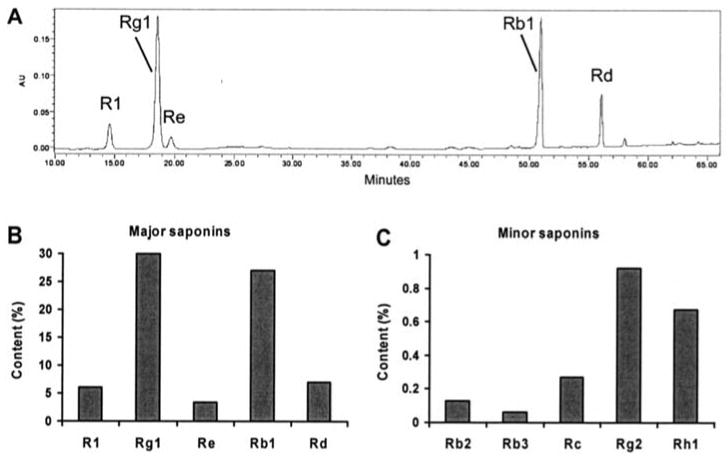

Figure 2.

HPLC analysis of notoginseng root extract (NGRE). (A) HPLC chromatogram of NGRE. (B) Contents of major saponins in NGRE. (C) Contents of minor saponins in NGRE.

The HPLC analysis of NGRE is shown in Fig. 2B. The major saponins in the extract were ginsenoside Rg1 (29.8%), Rb1 (27.0%), Rd (7.0%) and notoginsenoside R1 (6.0%). The contents of minor saponins in NGRE are shown in Fig. 2C.

Effects of NGRE on SW480 cell proliferation

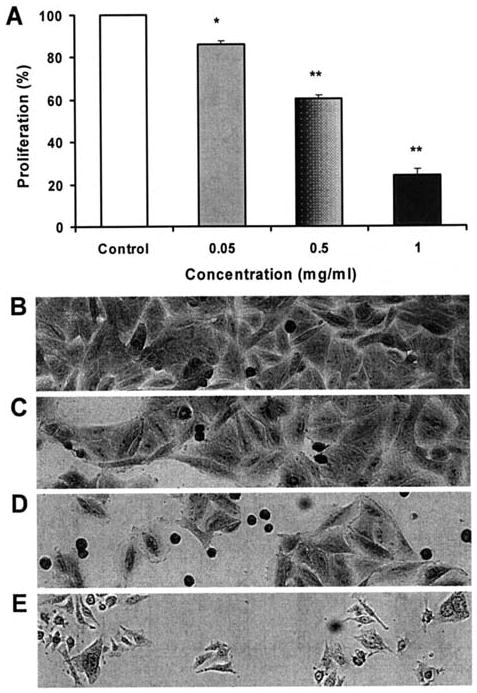

The anti-proliferative effects of NGRE on SW480 human colorectal cancer cells are shown in Fig. 3A. After treatment for 72 h, NGRE significantly inhibited cell proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner. Compared to the control (normalized to 100%), the cell growth was reduced by 14.1±1.5% (P<0.05), 39.6±1.0% (P<0.01), and 75.8±2.2% (P<0.01) at 0.05, 0.5, and 1.0 mg/ml, respectively. Accompanying cell morphological changes are shown in Fig. 3B.

Figure 3.

Anti-proliferative effects of NGRE on the SW480 human colorectal cancer cells after 72 h of treatment. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 vs. control (A), and representative morphological changes in SW480 cells after NGRE treatment (B-E). Concentration of NGRE: B, 0; C, 0.05 mg/ml; D, 0.5 mg/ml; and E, 1 mg/ml.

The anti-proliferative effect of the extract was also observed at different time-points. NGRE 1.0 mg/ml decreased the alive cell numbers by 26.0±0.8% at 24 h, 51.0±2.0% at 48 h, and 76.0±2.6% at 72 h. Since prolonging treatment time often induced unstable results in pilot experiments, the 72 h treatment time was selected for this study.

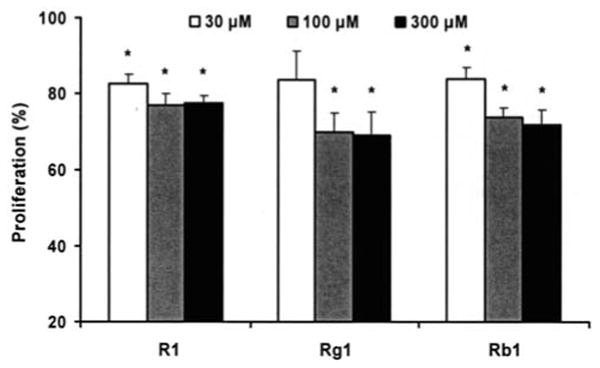

Effects of notoginsenoside R1, and ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1 on SW480 cell proliferation

To explore the inhibitory activities of single chemical constituents in notoginseng, the effects of notoginsenoside R1 (a unique constituent in notoginseng root), ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1 (found in relatively high contents in the root) were determined in SW480 cells. As shown in Fig. 4, compared to control, notoginsenoside R1 at concentrations of 30, 100, and 300 μM inhibited SW480 cell growth by 17.3±2.5%, 22.9±2.9%, and 22.5±2.0%, respectively (all P<0.05). Similar effects were observed with ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1.

Figure 4.

Anti-proliferative effects of notoginsenoside R1, ginsenosides Rg1 and Rb1 on SW480 cells after 72-h treatment. *P<0.05 vs. control (proliferation as 100%).

Effects of NGRE and ginsenoside Rb1 on DNA synthesis by measuring [3H]-thymidine incorporation

The effects of NGRE and ginsenoside Rb1 on the incorporation of SW480 cells were measured using [3H]-thymidine assay. At concentrations of 0.2 mg/ml, NGRE suppressed cellular incorporation of [3H]-thymidine by 27.0±4.4% (P<0.05). Ginsenosides Rb1 300 μM (∼0.3 mg/ml) had a statistically significant effect, by 19.2±2.7% (P<0.05). The extracts and ginsenoside Rb1 inhibited the cellular incorporation of [3H]-thymidine.

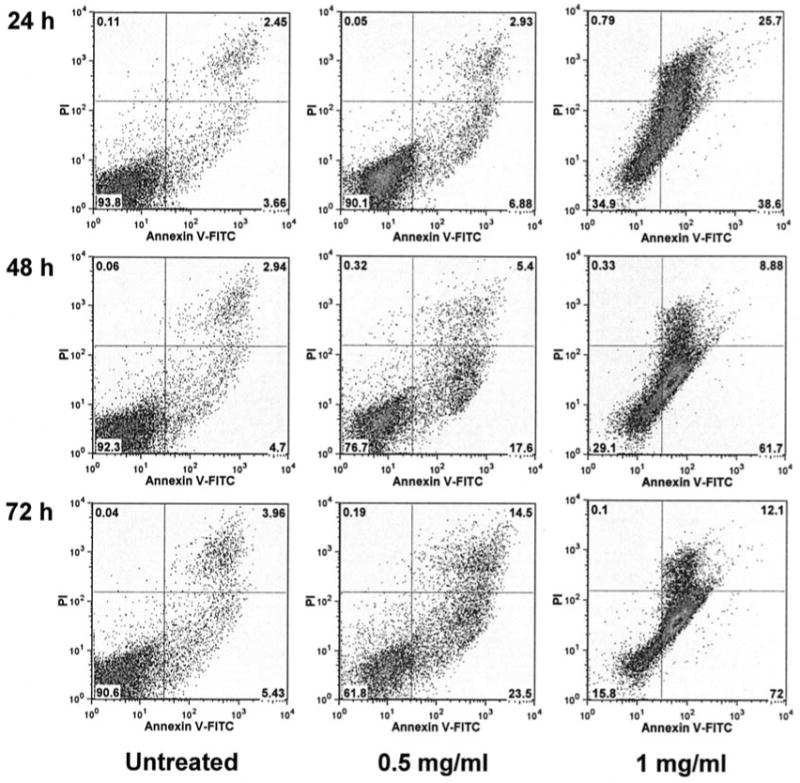

Effect of NGRE and notoginseng saponins on cell apoptosis

The cytograms of bivariate annexin V/PI analysis of SW480 cells after treatment with NGRE are shown in Fig. 5. Viable cells were negative for both PI and annexin V (lower left quadrant); early apoptotic cells (real apoptotic cells) were positive for annexin V and negative for PI (lower right quadrant); late apoptotic or necrotic cells displayed both positive for annexin V and PI (upper right quadrant); nonviable cells which underwent necrosis were positive for PI and negative for annexin V (upper left quadrant). The percentage of early apoptotic cells induced by 1 mg/ml NGRE after 24-h treatment increased to 38.6%, after 48 h to 61.7%, after 72 h to 72.0%, while the control was <5.4%. Treatment with 0.5 mg/ml of NGRE also increased the early apoptotic cells. The anti-proliferative effect of notoginseng extract was mediated by the induction of cell apoptosis.

Figure 5.

Apoptosis assay using flow cytometry after annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) staining. SW480 cells were treated with 0.5 and 1 mg/ml of NGRE for 24, 48 and 72 h. The percentage of different types of cells is shown. Apoptotic cells were positive for annexin V and negative for PI (lower right quadrant). Data shown are from two independent experiments.

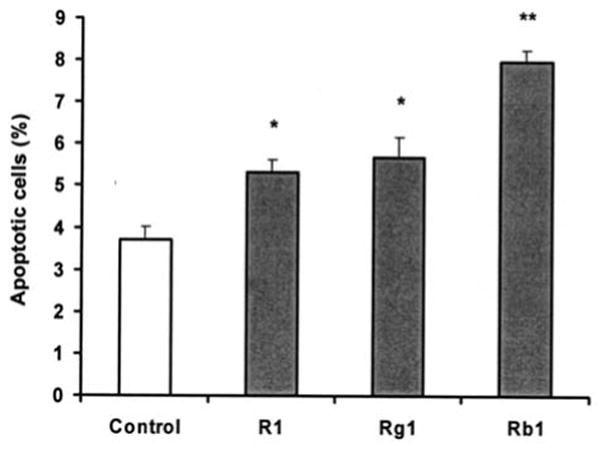

The main constituents in notoginseng are notoginsenoside R1 and ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1. The three saponins induced apoptosis in the SW480 cells. When cells were treated with 300 μM of saponins for 48 h, the percentage of apoptotic cells was 5.32±0.31% for notoginsenoside R1 (P<0.05), 5.69±0.46% for ginsenoside Rg1 (P<0.05), 7.97±0.29% for ginsenoside Rb1 (P<0.01), and 3.71±0.31% for control. The percentage of apoptotic cells increased significantly after treatment with the main constituents in notoginseng (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of three notoginseng saponins on SW480 cell apoptosis. SW480 cells were treated with 300 μM notoginsenoside R1, ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1 for 48 h. The percentage of apoptotic cells is shown.

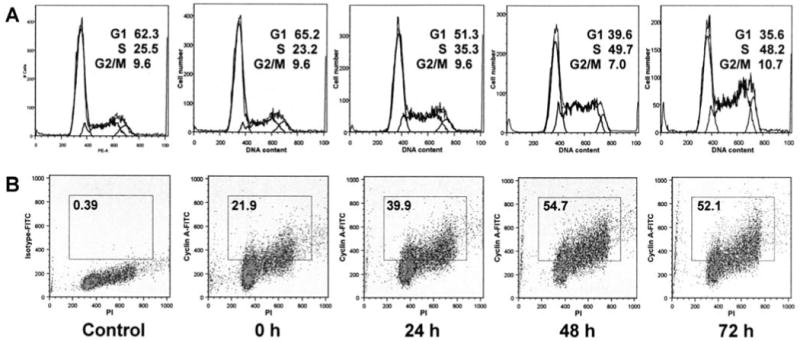

Effect of NGRE on cell cycle and expression of cyclin A

As shown in Fig. 7A, after treatment with NGRE, cells were arrested in the synthesis (S) phase. Compared with untreated cells (0 h: S-phase, 23.2%), after treatment with 0.5 mg/ml NGRE, the fraction of S-phase cells was increased to 35.3% at 24 h, 49.7% at 48 h, and 48.2% at 72 h. After 48 h of treatment, nearly 50% cells were in the S-phase.

Figure 7.

Cell cycle and cyclin A analysis of SW480 cells using flow cytometry. SW480 cells were treated with 0.5 mg/ml NGRE for 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. A, cell cycle profiles of SW480 cells. The percentage of cells in G1, S and G2/M phases is indicated. B, SW480 cells stained with cyclin A-FITC and propidium iodide. Untreated control cells were stained with isotype antibody and propidium iodide. The percentage of cyclin A positive cells is shown in the gate. Data shown are from two independent experiments.

After treatment with 0.5 mg/ml of NGRE, the expression of cyclin A was increased. Compared with untreated cells (0 h: 21.9%), the fraction of cyclin A positive cells was increased to 39.9% at 24 h, 54.7% at 48 h, and 52.1% at 72 h (Fig. 7B). The trend of increasing cyclin A was similar to the increase of S-phase cells. Both assays suggested that notoginseng extract can arrest SW480 cells in the S-phase.

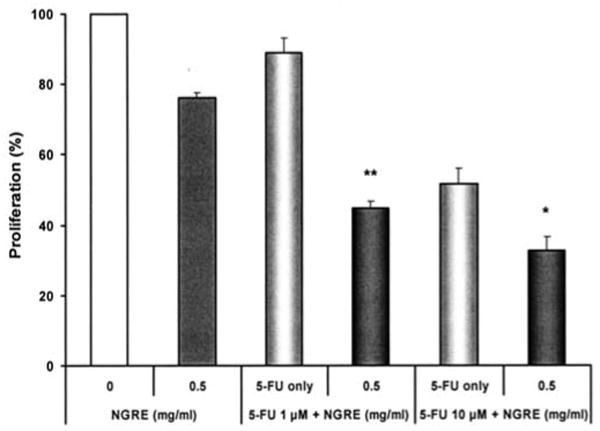

Effects of NGRE on the anti-proliferative actions of chemotherapeutic agents

As shown in Fig. 8, NGRE alone at 0.5 mg/ml decreased SW480 cell growth by 24.0±1.7%. When these cells were treated only with 5-FU at 1.0 and 10 μM, cell growth decreased by 11.0±4.0% and 48.3±2.0%, respectively. When NGRE 0.5 mg/ml was combined with 5-FU at the above concentrations, cell growth was decreased further (Fig. 8). For example, a treatment of NGRE at 0.5 mg/ml and 5-FU at 1.0 μM decreased cell growth by 55.1% (P<0.01 vs. 5-FU alone), suggesting that in combination with NGRE, the 5-FU dose can be reduced to achieve similar effects.

Figure 8.

Notoginseng root extract (NGRE) enhances the anti-proliferative effects of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) on SW480 human colorectal cancer cells. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 vs. 5-FU only.

In a separate experiment, NGRE was combined with irinotecan, another chemotherapy drug for human colorectal cancer. NGRE alone at 0.05 and 0.5 mg/ml decreased cell growth by 11.0±2.0, and 29.0±1.2%, respectively. Irinotecan alone at 20 μM decreased cell growth by 46.4±4.1%. A combined treatment of NGRE at 0.05 or 0.5 mg/ml and irinotecan 20 μM further decreased the cell growth by 64.2±0.8% and 66.2±1.0% (both P<0.05 vs. irinotecan alone), respectively (Fig. 9). Even at a low concentration, NGRE enhanced the action of irinotecan.

Figure 9.

Notoginseng root extract (NGRE) enhances the anti-proliferative effects of irinotecan (IRN) on SW480 human colorectal cancer cells. **P<0.01 vs. IRN only.

In a third experiment, however, NGRE at 0.5 mg/ml did not enhance the action of doxorubincin at 1.0 μM (doxorubincin alone by 51.0±0.9%; NGRE at 0.5 mg/ml and doxorubincin, by 46.3±3.3%). Doxorubincin is a chemotherapy drug used for digestive malignancies.

Discussion

Notoginseng belongs to the same genus of plants as Asian ginseng and American ginseng. Both possess potential anti-cancer activities and have ginsenosides, such as Rg3 and Rh2, that are active compounds (18-20). Several ginsenosides have regulated the proliferation of cancer cells in vitro and have sensitized cancer cells to chemotherapy (21-23). The main constituents in notoginseng root are notoginsenoside R1, and ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1. The anti-tumor effects of notoginseng were observed in sarcoma and prostate cancer cells, but the responsible compounds have not been identified (24,25). In this study, we observed the tumoricidal activity of notoginseng and active compounds on invasive SW480 human colorectal cancer cells. We showed significant antiproliferative effects of notoginseng root extract on the cells, and a high concentration of ginsenoside Rb1 and Rg1 in the extract was responsible for this activity.

To explore the possible mechanisms of notoginseng's anticancer activity, we evaluated the effect of the extract on the incorporation of [3H]-thymidine in SW480 cells by using the [3H]-thymidine labeling assay. Our data suggest that the root extract directly inhibits the synthesis of DNA in the cells (17).

Apoptosis is a homeostatic mechanism that balances cell division and cell death to maintain the appropriate number of cells in the body. A balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis controls normal organ development. Uncontrolled proliferation or suppressed apoptosis is strong evidence of cancer. Inducing apoptosis in tumor cells is an important way to treat cancer (26,27). In our experiment, notoginseng extract and the main constituents in notoginseng inhibited proliferation of SW480 human colorectal cancer cells by inducing apoptosis. The ratio of apoptotic cells detected by flow cytometry after annexin V/PI staining increased markedly with notoginseng root extract.

Cell cycle arrest may trigger the DNA repair machine, leading to apoptosis. In our study, notoginseng extract arrested cells in the S-phase. Cell cycle progression is regulated by the activity of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Cyclin A is required for S-phase and passage through G2 (28). To obtain information on the molecular mechanism involved in the arrest of the cell cycle in the S-phase, the expression of cyclin A was determined. The fraction of cyclin A positive cells increased to 54.7% after treatment with notoginseng extract for 48 h; in untreated cells the fraction was only 21.9%. The accumulation of cyclin A was critical to promote cell cycle arrest in the S-phase.

The most successful treatment regimens for cancer include combination chemotherapy, which is often more effective than single chemotherapy because of additive or synergistic effects. For many years, the chemotherapeutic treatment of advanced colorectal cancers was systemic use of 5-FU combined with leucovorin. This treatment course is now being replaced with sequential and/or concurrent multimodal chemotherapeutic regimens that combine 5-FU with other chemotherapeutic agents. In a Phase III trial that combined 5-FU, leucovorin, and irinotecan, progression-free survival and overall survival times were greater than with 5-FU and leucovorin alone (29). These results have been confirmed by other clinical trials (30). Although the addition of irinotecan to the 5-FU regimen increased survival time, it also increased the severity of adverse effects experienced by the patients. Another example is doxorubicin, an anthracycline antibiotic widely used for chemotherapy against solid tumors. The efficiency of doxorubicin is limited because of dose-related toxicity (31). Doxorubicin has some effect against colorectal cancer as part of a combination chemotherapy regimen (32,33).

It has been reported that notoginseng increased tumor radiosensitivity to the cytotoxic effect of ionizing radiation (25). In this study, we evaluated the effects of notoginseng in enhancing the action of selected chemotherapeutic agents. Our data suggest that notoginseng has the potential to enhance the effects of 5-FU and irinotecan without affecting doxorubicin's activity. It appears that 5-FU- and irinotecan-induced toxicity can be reduced by using notoginseng as a chemo-adjuvant. When notoginseng potentiates the tumoricidal effects of chemotherapeutic agents, smaller chemotherapy doses can be used. Identifying non-toxic chemo-adjuvants among herbal medicines is an essential step in advancing the treatment of the cancer. We intend to test notoginseng as a chemo-adjuvant in in vivo studies in the future. Data obtained from our studies will have the potential to advance treatment regimens and improve the quality of life for patients suffering from colorectal cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH/NCCAM grants AT002445 and AT003255.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Tiwari RC, Murray T, Ghafoor A, Samuels A, Ward E, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:8–29. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin AR, Carides AD, Pearson JD, Horgan K, Elmer M, Schmidt C, Cai B, Chawla SP, Grunberg SM. Functional relevance of antiemetic control. Experience using the FLIE questionnaire in a randomised study of the NK-1 antagonist aprepitant. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1395–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnell FM. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: the importance of acute antiemetic control. Oncologist. 2003;8:187–198. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-2-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang CZ, Basila D, Aung HH, Mehendale SR, Chang WT, McEntee E, Guan X, Yuan CS. Effects of ganoderma lucidum extract on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in a rat model. Am J Chin Med. 2005;33:807–815. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X05003429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadeghi H, Yazdanparast R. Isolation and structure elucidation of a new potent anti-neoplastic diterpene from Dendrostellera lessertii. Am J Chin Med. 2005;33:831–837. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X05003387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng TB. Pharmacological activity of sanchi ginseng (Panax notoginseng) J Pharm Pharmacol. 2006;58:1007–1019. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.8.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang CZ, McEntee E, Wicks S, Wu JA, Yuan CS. Phytochemical and analytical studies of Panax notoginseng (Burk.) FH Chen. J Nat Med. 2006;60:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei F, Zou S, Young A, Dubner R, Ren K. Effects of four herbal extracts on adjuvant-induced inflammation and hyperalgesia in rats. J Altern Complement Med. 1999;5:429–436. doi: 10.1089/acm.1999.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konoshima T, Takasaki M, Tokuda H. Anti-carcinogenic activity of the roots of Panax notoginseng. II. Biol Pharm Bull. 1999;22:1150–1152. doi: 10.1248/bpb.22.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang ZG, Sun HX, Ye YP. Ginsenoside Rd from Panax notoginseng is cytotoxic towards HeLa cancer cells and induces apoptosis. Chem Biodivers. 2006;3:187–197. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200690022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cui XM, Wang CL, Chen ZJ, Wang Y. Estimate of environmental condition on GAP culture of Panax notoginseng. Chin Tradit Herbal Drugs. 2002;33:75–77. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong TT, Cui XM, Song ZH, Zhao KJ, Ji ZN, Lo CK, Tsim KW. Chemical assessment of roots of Panax notoginseng in China: regional and seasonal variations in its active constituents. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:4617–4623. doi: 10.1021/jf034229k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu QF, Fang XL, Chen DF, Li JC. Studies on formulations of Panax notoginsenosides for intranasal administration. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2003;38:859–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang CZ, Luo X, Zhang B, Song WX, Ni M, Mehendale S, Xie JT, Aung HH, He TC, Yuan CS. Notoginseng enhances anti-cancer effect of 5-fluorouracil on human colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;60:69–79. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0350-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang CZ, Wu JA, McEntee E, Yuan CS. Saponins composition in American ginseng leaf and berry assayed by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:2261–2266. doi: 10.1021/jf052993w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie JT, Wang CZ, Wicks S, Yin JJ, Kong J, Li J, Li YC, Yuan CS. Ganoderma lucidum extract inhibits proliferation of SW 480 human colorectal cancer cells. Exp Oncol. 2006;28:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gieni RS, Li Y, HayGlass KT. Comparison of [3H]thymidine incorporation with MTT- and MTS-based bioassays for human and murine IL-2 and IL-4 analysis. Tetrazolium assays provide markedly enhanced sensitivity. J Immunol Methods. 1995;187:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00170-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helms S. Cancer prevention and therapeutics: Panax ginseng. Altern Med Rev. 2004;9:259–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duda RB, Zhong Y, Navas V, Li MZ, Toy BR, Alavarez JG. American ginseng and breast cancer therapeutic agents synergistically inhibit MCF-7 breast cancer cell growth. J Surg Oncol. 1999;72:230–239. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199912)72:4<230::aid-jso9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang CZ, Zhang B, Song WX, Wang A, Ni M, Luo X, Aung HH, Xie JT, Tong R, He TC, Yuan CS. Steamed American ginseng berry: ginsenoside analyses and anticancer activities. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:9936–9942. doi: 10.1021/jf062467k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jia WW, Bu X, Philips D, Yan H, Liu G, Chen X, Bush JA, Li G. Rh2, a compound extracted from ginseng, hypersensitizes multidrug-resistant tumor cells to chemotherapy. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;82:431–437. doi: 10.1139/y04-049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HS, Lee EH, Ko SR, Choi KJ, Park JH, Im DS. Effects of ginsenosides Rg3 and Rh2 on the proliferation of prostate cancer cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;27:429–435. doi: 10.1007/BF02980085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Baba M, Uehara H, Nakaizumi A, Shinkai K, Akedo H, Funai H, Ishiguro S, Kitagawa I. Inhibition by ginsenoside Rg3 of bombesin-enhanced peritoneal metastasis of intestinal adenocarcinomas induced by azoxymethane in Wistar rats. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1997;15:603–611. doi: 10.1023/a:1018491314066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung VQ, Tattersall M, Cheung HT. Interactions of a herbal combination that inhibits growth of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;53:384–390. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0746-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen FD, Wu MC, Wang HE, Hwang JJ, Hong CY, Huang YT, Yen SH, Ou YH. Sensitization of a tumor, but not normal tissue, to the cytotoxic effect of ionizing radiation using Panax notoginseng extract. Am J Chin Med. 2001;29:517–524. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X0100054X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed JC, Pellecchia M. Apoptosis-based therapies for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2005;106:408–418. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu WY, Guo HZ, Qu GQ, Han J, Guo DA. Mechanisms of pseudolaric Acid B-induced apoptosis in bel-7402 cell lines. Am J Chin Med. 2006;34:887–899. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X06004363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakayama KI, Nakayama K. Ubiquitin ligases: cell-cycle control and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:369–381. doi: 10.1038/nrc1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saltz LB, Cox JV, Blanke C, Rosen LS, Fehrenbacher L, Moore MJ, Maroun JA, Ackland SP, Locker PK, Pirotta N, Elfring GL, Miller LL. Irinotecan plus fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. Irinotecan Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:905–914. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009283431302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohne CH, Wils J, Lorenz M, Schoffski P, Voigtmann R, Bokemeyer C, Lutz M, Kleeberg C, Ridwelski K, Souchon R, El-Serafi M, Weiss U, Burkhard O, Ruckle H, Lichnitser M, Langenbuch T, Scheithauer W, Baron B, Couvreur ML, Schmoll HJ. Randomized phase III study of high-dose fluorouracil given as a weekly 24-hour infusion with or without leucovorin versus bolus fluorouracil plus leucovorin in advanced colorectal cancer: European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer Gastrointestinal Group Study 40952. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3721–3728. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss RB. The anthracyclines: will we ever find a better doxorubicin? Semin Oncol. 1992;19:670–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stathopoulos GP, Rigatos SK, Malamos NA, Stathopoulos JG, Thallasinou P, Papazachariou E, Antoniou F, Kondopodis E, Xynotroulas J. Long-term survival of patients with advanced colorectal cancer may not be due to the response to chemotherapy. Oncol Rep. 2004;12:1295–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schally AV, Nagy A. Chemotherapy targeted to cancers through tumoral hormone receptors. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15:300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]