Abstract

Background

Former studies have shown that extract from American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) may possess certain antiproliferative effects on cancer cells. In this study, the chemical constituents of both untreated and heat-processed American ginseng and their antiproliferative activities on human breast cancer cells were evaluated.

Materials and Methods

American ginseng roots were steamed at 120°C for 1 h or 2 h. The major ginsenosides in the two steamed and in the unsteamed extracts were quantitatively determined using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The antiproliferative activities of these extracts and individual ginsenosides on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were assayed using the MTS method. The effects of the extracts and the ginsenosides on the induction of cell apoptosis, the expression of cyclins A and D1, and cell cycle arrest were evaluated.

Results

Compared to the untreated extract, heat-processing reduced the content of ginsenosides Rb1, Re, Rc and Rd, and increased the content of Rg2 and Rg3. After 2 h steaming, the percent content of ginsenoside Rg3 was increased from 0.06% to 5.9%. Compared to the unsteamed extract, the 2 h steamed extract significantly increased the antiproliferative activity and significantly reduced the number of viable cells. The steamed extract also significantly reduced the expression of cyclin A and cyclin D1. The cell cycle assay showed that the steamed extract and ginsenoside Rg3 arrested cancer cells in G1-phase.

Conclusion

Heat-processing of American ginseng root significantly increases antiproliferative activity and influences the cell cycle profile.

Keywords: Panax quinquefolius L., heat-processing, antiproliferation, human breast cancer, HPLC analysis, ginsenoside Rg3, apoptosis, cell cycle

American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.), which belongs to the genus Panax L. in the Araliaceae family, is a commonly used herb in the United States (1). Panax is a small genus and nearly all the species in this genus are important herbal medicines, especially Asian ginseng (Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer) (2). Since Asian ginseng has been used as a herbal medicine throughout history in oriental countries, many studies have been conducted on its constituents and its pharmacological effects (3). Asian ginseng has many reported health benefits, including anticancer activities (4-6). In the 1990s, a case–control study on over a thousand Korean subjects showed that long-term ginseng consumption was associated with a decreased risk for many different malignancies (7, 8). In contrast to many studies on Asian ginseng’s anticancer effects, investigation of American ginseng is limited (4) and its mechanisms of action are largely unknown.

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed form of cancer among women. Breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in nearly all developed countries, showing an increased incidence over the last decades, and the expected number of new U.S. patients in 2008 is 182,460, with 40,480 deaths (9). The clinical management of breast cancer invariably involves diverse conventional modalities, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation (10). The complex characteristics of breast cancer may also require some alternative management to improve the therapeutic efficacy of conventional treatment and the quality of life for cancer patients (11).

We have previously observed that American ginseng decreased chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in a rat model (12), while not affecting the chemotherapy anticancer action in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells (13). In separate studies, we have shown that steam-processing of American ginseng significantly improved the anticancer ginsenoside profile and the antiproliferative activity on human colorectal cancer cells (14, 15). Since the root of American ginseng changes from white to red during steam-processing, steamed P. quinquefolius root is therefore referred to as red American ginseng. However, in our former studies, only the ginsenoside contents of the crude plant materials and the activities on human colorectal cancer cells were analyzed. Additionally, the antiproliferative mechanism of American ginseng root extract has not been studied.

Currently, the most popular herbal products are in extract forms. New regulations released by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on alternative complementary supplements require botanical extracts to be standardized (16). The contents of ginsenosides in the extracts were not previously assayed. In this study, the content of representative ginsenosides in unsteamed and steamed American ginseng root extracts was determined using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). In addition to the cell line MCF-7, MDA-MB-230 human breast cancer cells were also used to evaluate the chemopreventive activities of unsteamed and steamed American ginseng root extracts and four ginsenosides. The effects of the American ginseng extracts and single compounds on apoptosis and the cell cycle were also evaluated.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Ginsenoside standards Rb1, Rc, Rd, Re, Rg2 and Rg3, purchased from Delta Information Center for Natural Organic Compounds (Xuancheng, AH, China), were of biochemical reagent grade and at least 95% pure as confirmed by HPLC. HPLC grade ethanol, n-butanol, acetonitrile and absolute ethanol were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Trypsin, RPMI-1640 medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin/streptomycin solution (200×), propidium iodide (PI) and RNase were obtained from Mediatech, Inc. (Herndon, VA, USA). A CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution cell proliferation assay kit was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA). Annexin V- fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), cyclin A-FITC and cyclin D1-FITC were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA).

Plant materials, processing and extraction

The root of P. quinquefolius L. was collected from Roland Ginseng Limited Liability Company (Wausau, WI, USA). The voucher specimen was authenticated by Dr. Chong-Zhi Wang and deposited at the Tang Center for Herbal Medicine Research at the University of Chicago. For the heat-processing of American ginseng, the roots were steamed at 120°C for 1 h or 2 h. The fresh and steamed roots were lyophilized to obtain dried samples. The extraction process was as follows. The dried roots were ground and extracted with 70% ethanol. The solvent of the extract solution was evaporated under vacuum. The dried extract was dissolved in water; and then extracted with water-saturated n-butanol. The n-butanol phase was evaporated under vacuum and then lyophilized.

HPLC analysis

HPLC analysis was conducted on a Waters 2960 instrument with a Waters 996 photodiode array detector (Milford, MA, USA). The separation was carried out on an Alltech Ultrasphere C18 column (5 μ, 250×3.2 mm I.D.) (Deerfield, IL, USA) with a guard column (Alltech Ultrasphere C18, 5 μ, 7.5×3.2 mm I.D.). Acetonitrile (solvent A) and water (solvent B) were used. Gradient elution started with 18% solvent A and 82% solvent B, changed to 21% A over 20 min; to 26% A over 3 min and held for 19 min; to 36% A over 13 min; to 50% A over 9 min; to 95% A over 2 min and held over 3 min and finally changed to 18% A for 3 min and held for 8 min. The flow rate was 1.0 ml/min and the detection wavelength was set to 202 nm. All the tested solutions were filtered through Millex 0.2-μm nylon membrane syringe filters (Millipore Co., Bedford, MA, USA) before use. The contents of ginsenosides in each sample were calculated using standard curves of ginsenosides.

Cell culture

The human breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and grown in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 50 IU penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Cell proliferation analysis

Unsteamed and steamed American ginseng root extracts and ginsenosides were dissolved in 50% ethanol and were stored at 4°C before use. The MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 96-well plates. After 1 day, various concentrations of extracts/ginsenosides were added to the wells. The final concentration of ethanol was 0.5%. The controls were exposed to culture medium containing 0.5% ethanol without drugs. All the experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. The cell proliferation was evaluated using MTS assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, at the end of the drug exposure period, the medium was replaced with 100 μl of fresh medium, 20 μl of MTS reagent (CellTiter 96 Aqueous Solution) in each well and the plate was returned to the incubator for 1-2 h. A 60-μl aliquot of medium from each well was transferred to an ELISA 96-well plate and its absorbance at 490 nm was recorded (1, 17). The results were expressed as percentage of the control (ethanol controls set at 100%).

Apoptosis assay

The MCF-7 cells were seeded in 24-well tissue culture plates. After culturing for 1 day, the medium was changed and the extracts/ginsenosides were added. After treatment for 48 h, the cells floating in the medium were collected. The adherent cells were detached with 0.05% trypsin. Then the culture medium containing 10% FBS (and floating cells) was added to inactivate the trypsin. After being pipetted gently, the cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 1500 g. The supernatant was removed and the cells were stained with annexin V-FITC and PI according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Annexin V-FITC detects translocation of phosphatidylinositol from the inner to the outer cell membrane during early apoptosis, and PI can enter the cell in late apoptosis or necrosis. Untreated cells were used as control for the double staining. The cells were analyzed immediately after staining using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA) and FlowJo 7.1.0 software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA). For each measurement, at least 20,000 cells were counted.

Cyclin A and cyclin D1 assay

The MCF-7 cells were seeded in 24-well tissue culture plates. On the second day, the medium was changed and the cells were treated with the extracts. The cells were incubated for 48 h before harvesting. The cells were fixed gently with 80% ethanol in a freezer for 2 h and were then treated with 0.25% Triton® X-100 for 5 min in an ice bath. The cells were resuspended in 300 μl of PBS containing 40 μg/ml PI and 0.1 mg/ml RNase. Then, 20 μl of cyclin A-FITC or cyclin D1-FITC was added to the cell suspension. The cells were incubated in a dark room for 20 min at room temperature and analyzed with a FACScan flow cytometer. For each measurement, at least 20,000 cells were counted.

Cell cycle assay

After 48 h treatment with the extracts/ginsenosides, the MCF-7 cells were harvested in similar manner to that used in the cyclin assay. Then, the cells were stained with PI and analyzed with a FACScan flow cytometer. For each measurement, at least 20,000 cells were counted.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) with n=3. A one-way ANOVA determined whether the results had statistical significance. In some cases, Student’s t-test was used for comparing two groups. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Ginsenoside composition in extracts during heat processing

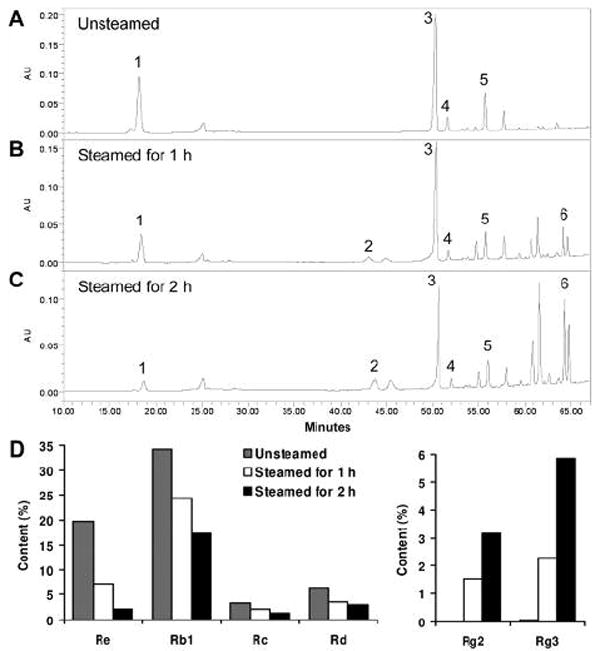

The chemical structures of representative ginsenosides in unsteamed and steamed American ginseng extracts are shown in Figure 1. From the HPLC chromatograms ginsenosides Rb1 and Re were the major constituents in the unsteamed American ginseng root extract (Figure 2A). After 2 h steaming, ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg3 became the main constituents (Figure 2C). During heat-processing, the peak areas of ginsenosides Re, Rb1, Rc and Rd decreased markedly, while ginsenosides Rg2 and Rg3 increased (Figure 2A-C). The content changes of the major constituents in the extracts are shown in Figure 2D. In the unsteamed extract, the content of ginsenosides Re, Rb1, Rc and Rd were 19.8%, 34.2%, 3.4% and 6.5%, decreasing to 2.1%, 17.3%, 1.2% and 2.9%, respectively, after 2 h steaming. On the other hand, the contents of ginsenosides Rg2 and Rg3 were 0% and 0.06% in the unsteamed extract, while after 2 h steaming, they increased to 3.2% and 5.9%, respectively.

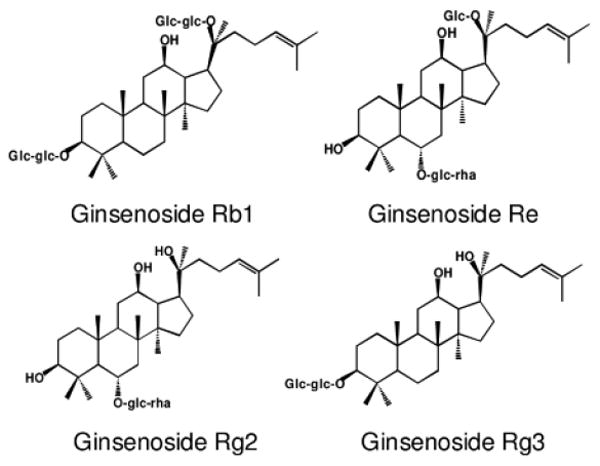

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of four representative ginsenosides in American ginseng.

Figure 2.

HPLC analysis of American ginseng extracts. Chromatograms of extracts from unsteamed (A), 1 h steamed (B) and 2 h steamed (C) American ginseng roots. Ginsenoside peaks: (1) Re, (2) Rg2, (3) Rb1, (4) Rc, (5) Rd, and (6) Rg3. Contents of ginsenosides in extracts are shown in (D); note the scale of content (%) differs between the left and right groups.

Antiproliferative effects of extracts and ginsenosides on human breast cancer cells

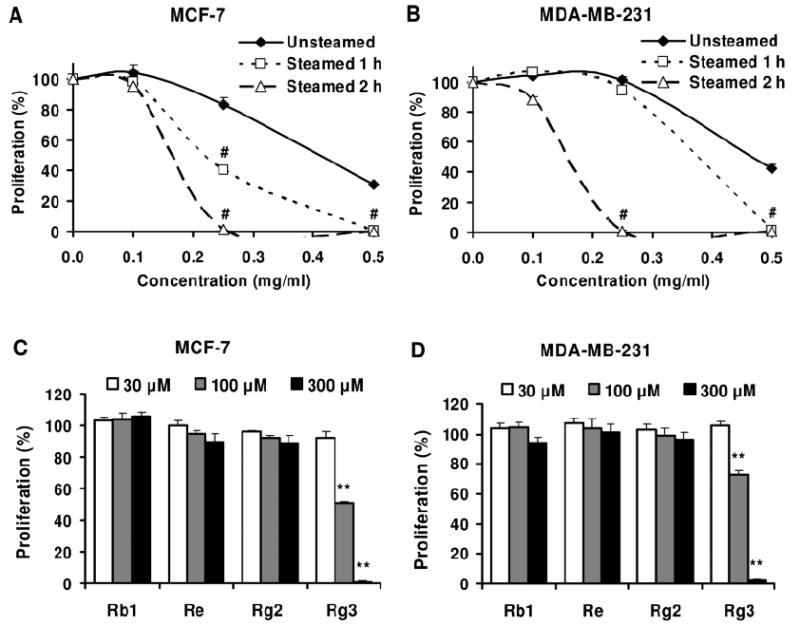

At 0.25 mg/ml, the unsteamed extract inhibited MCF-7 cell growth by 17.0% and after steaming for 1 h, the extract inhibited cell growth by 60.0% (p<0.01 vs. unsteamed extract). Moreover, after the cells were treated with the 2 h steamed extract, cell growth was inhibited absolutely. At 0.5 mg/ml, extracts from the 1 h and 2 h steamed roots inhibited cell growth over 99.6% (Figure 3A). For the MDA-MB-231 cells, at 0.25 mg/ml, the extracts from the unsteamed and 1 h steamed roots did not show an antiproliferative effect, while the extract from the 2 h steamed roots showed a very strong effect, as cell growth was inhibited by 99.2% (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effects of American ginseng extracts and ginsenosides on proliferation of MCF-7 (A, C) and MDA-MB-231 (B, D) human breast cancer cells. Cells were treated with extracts (A, B) or ginsenosides (C, D) for 72 h, and then assayed by MTS method. #, p<0.01 vs. unsteamed extract; **, p<0.01 vs. control (100%).

Four representative ginsenosides were used to test for antiproliferative effects on the breast cancer cells, two ginsenosides (Rb1 and Re) that were major constituents in unsteamed American ginseng roots, and two other ginsenosides (Rg2 and Rg3) that were major constituents in the steamed roots. At 30-300 μM, after 72 h treatment, ginsenosides Rb1, Re and Rg2 did not show antiproliferative effects on the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. Ginsenoside Rg3 showed an antiproliferative effect on both the cancer cell lines. At 100 μM, ginsenoside Rg3 inhibited cell growth by 49.8% in the MCF-7 cells and by 27.3% in the MDA-MB-231 cells (both p<0.01 vs. untreated control). At 300 μM, ginsenoside Rg3 almost completely inhibited cell growth in both the cell lines (Figure 3C and 3D).

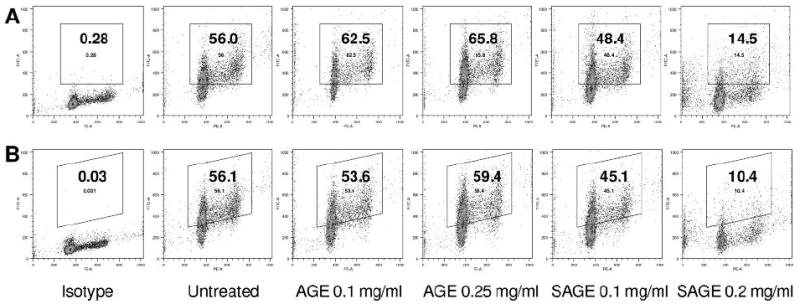

Apoptotic effect of extracts and ginsenosides on MCF-7 cells

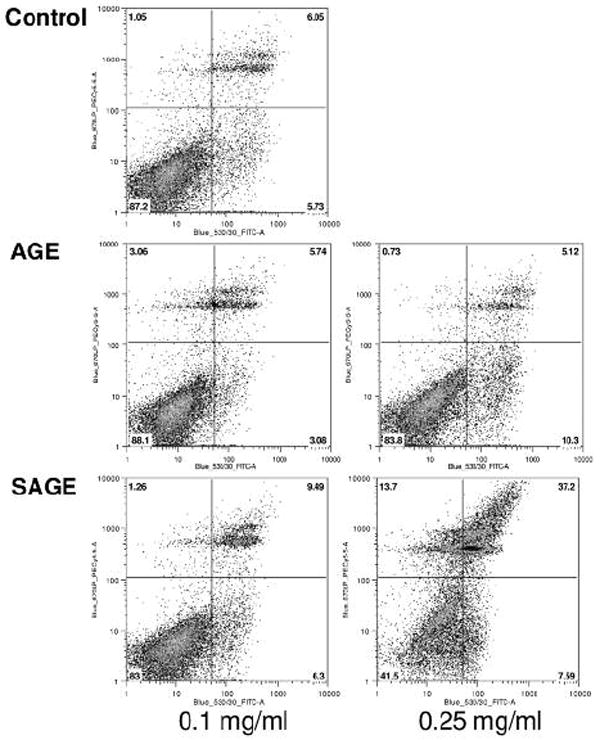

As shown in Figure 4, compared to the untreated control (early apoptosis 5.7%, late apoptosis/necrosis 6.1%), after treatment with 0.25 mg/ml for 48 h, the unsteamed extract increased early apoptosis to 10.3%, but did not influence late apoptosis/necrosis (5.2%). After treatment with extract from the 2 h steamed roots, early apoptosis increased slightly (7.6%), and late apoptosis/necrosis increased significantly to 37.2%. For the viable cells, the control was 88.1%, the unsteamed extract was 83.8%, while the 2 h steamed extract was 41.5%. The steamed extract markedly reduced the proportion of viable cells.

Figure 4.

Apoptosis assay using flow cytometry after annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) staining. MCF-7 cells were treated with 0.1 or 0.25 mg/ml of unsteamed (AGE) or 2 h steamed extract (SAGE) for 48 h. Viable cells are in the lower left quadrant, early apoptotic cells are in the lower right quadrant, late apoptotic or necrotic cells are in the upper right quadrant and non-viable necrotic cells are in upper left quadrant.

Compared to the control (5.5%), after treatment with 100-300 μM of ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg3 for 48 h, the percentage of early apoptotic cells was not increased (less than 6.2% and 5.8%, respectively). At the concentration of 300 μM, the ginsenosides Re and Rg2 increased the percentage of early apoptosis to 13.0% and 9.1%, respectively.

Effect of extracts on the expression of cyclins in the MCF-7 cells

The protein expression of cyclin A and cyclin D1 were evaluated by flow cytometry after staining with cyclin A-FITC and cyclin D1-FITC. The percentage of cyclin A-positive cells in the untreated control was 56.0%. After treatment with 0.1 and 0.25 mg/ml of the unsteamed extract for 48 h, the proportion of cyclin A-positive cells increased to 62.5% and 65.8%, while after treatment with 0.1 and 0.2 mg/ml of the 2 h steamed extract, the cyclin A-positive cells decreased to 48.4% and 14.5%, respectively (Figure 5A). The unsteamed extract did not influence the expression of cyclin D1, while the 2 h steamed extract reduced the expression of cyclin D1 markedly (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Cyclin A and D1 analysis of MCF-7 cells using flow cytometry. After treatment for 48 h, MCF-7 cells were stained with cyclin A/PI (A) and cyclin D1/PI (B). Isotype: untreated cells were stained with isotype antibody/PI. The percentage of cyclin A-(A) and cyclin D1-(B) positive cells is shown in the gate. AGE, unsteamed extract; SAGE, 2 h steamed extract.

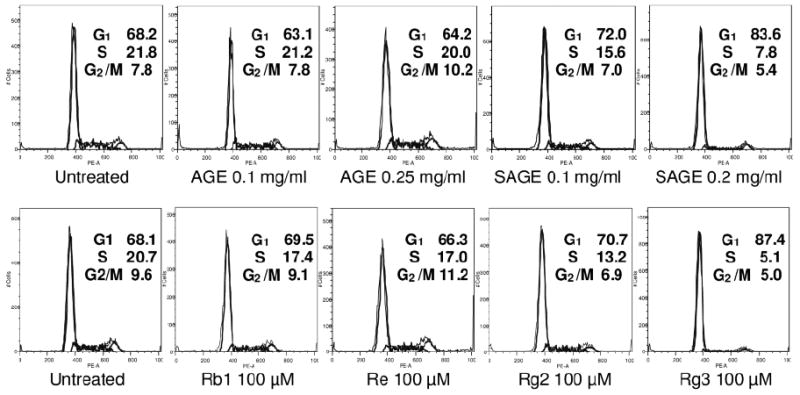

Effects of extracts and ginsenosides on MCF-7 cell cycle

The unsteamed extract did not influence the cell cycle profile (Figure 6). Compared to the untreated control (G1, 68.2%), 0.2 mg/ml of the 2 h steamed extract increased the percentage of cells in the G1-phase to 83.6%. The single compounds, ginsenosides Rb1, Re and Rg2, had almost no influence on the cell cycle. Ginsenoside Rg3, a previously recognized anticancer compound, increased the G1 fraction to 87.4% (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effects of extracts and ginsenosides on the cell cycle. After treatment with extracts or ginsenosides for 48 h, the MCF-7 cells were stained with PI and assayed using flow cytometry. The percentage of cells in G1-, S- and G2/M-phases are indicated. AGE, unsteamed extract; SAGE, 2 h steamed extract.

Discussion

Herbal medicines are comprised of a complicated mixture of biologically active compounds. The concentrations of these compounds may vary significantly depending on many intrinsic and extrinsic factors such as genetics, season, geographical distribution, plant growth, and the production and extraction processes (18). Thus, the identification and analysis of the medicinal components are very important issues in the quality assurance of herbal products. Since American ginseng from Wisconsin is a reliable ginseng source (19), in this study, the American ginseng from Roland Ginseng was used. The plant material was identified according to the United States Pharmacopoeia NF 21, monograph: American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.). The contents of the major ginsenosides in the different American ginseng extracts were determined using HPLC, and the extracts were standardized, thus the quantitative assay data are critical references for future studies.

Heat processing of American ginseng changes the constituent profile and we have previously reported the steaming temperatures and times in relation to changes of ginsenosides in the crude herb (15). In the present study, in the unsteamed extract, the content of ginsenoside Rb1 was 34.2%, and the total of six ginsenosides was 63.9%. The total ginsenoside content in the extract was very high, suggesting that the extraction and purification method used in this study were efficient.

Ginsenoside Rg3, a previously recognized anticancer compound (4), was detected as only a trace ginsenoside (0.06%) in the unsteamed extract; but after 2 h steaming, the content of Rg3 increased to 5.9%, becoming a main constituent. Therefore, steaming the American ginseng increased the Rg3 content markedly. Pharmacological studies showed that heat processing of American ginseng increased the antiproliferative effect significantly, and the effects of the 2 h steamed root extract were more potent than that of the root steamed for 1 h.

Using both cancer cell lines (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231), the ginsenosides Rb1 and Re, as found in the unsteamed extract, almost had no effect at the concentration range of 30-300 μM. Ginsenoside Rg3, which was taken from steamed extract, showed strong antiproliferative activity. The increase of the antiproliferative effect of steam-processing is based on the increase of anticancer constituents.

Apoptosis is considered an important pathway in the inhibition of cancer cells by many anticancer agents (20, 21). However, apoptotic induction in the MCF-7 cells was not confirmed by the current data. The steamed extract did not show obvious activity on early apoptosis, which is considered real apoptosis. The antiproliferative effect of red American ginseng extract on human breast cancer cells may be caused by other mechanisms.

Recent studies have found that the overexpression of cyclin D1 promoted tumor cell growth and conferred resistance to chemotherapy (22). The cyclin assay in the present study showed that the American ginseng extracts regulated the expression of cyclin A and cyclin D1 in the MCF-7 cells. The red (steamed) American ginseng extract reduced the expression of cyclin A and cyclin D1 significantly. Since cyclins are important regulatory proteins in the cell cycle, the inhibition of cell growth by the steamed extract may be caused by an influence on the cell cycle. The data showed that the red American ginseng extract arrested the cells in the G1-phase, and reduced the percentage of cells in the S and G2/M-phases. Treatment with 100 μM of ginsenosides Rb1, Re and Rg2 for 48 h did not influence the cell cycle profile, but ginsenoside Rg3, a main constituent in red American ginseng, arrested the cells in the G1-phase and this result was similar to that found with the red American ginseng extract.

At a concentration of 0.25 mg/ml, the 2 h steamed extract inhibited cell growth absolutely. At that concentration, the 2 h steamed extract contained 18.6 μM of ginsenoside Rg3. However, even 30 μM of ginsenoside Rg3 did not show significant antiproliferative activity. From the HPLC chromatogram of the 2 h steamed extract (Figure 2 C), several peaks of unidentified compounds can be seen. Other more potent compounds probably existed in the red American ginseng extract, and these compounds may have similar effects to Rg3 on the cell cycle. This should be the focus of future studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NIH/NCCAM) AT002445 and AT003255 (to C.S.Y.), from the American Cancer Society and Leukemia Society Scholarship and a Fletcher Scholarship of the Cancer Research Foundation (to W.D.), and from the U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (NIH/NCI) CA106569 and American Cancer Society RSG-05-254-01DDC (to T.C.H.).

References

- 1.Wang CZ, Luo X, Zhang B, Song WX, Ni M, Mehendale S, Xie JT, Aung HH, He TC, Yuan CS. Notoginseng enhances anticancer effect of 5-fluorouracil on human colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;60:69–79. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0350-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286:208–216. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attele AS, Wu JA, Yuan CS. Ginseng pharmacology: multiple constituents and multiple actions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:1685–1693. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helms S. Cancer prevention and therapeutics: Panax ginseng. Altern Med Rev. 2004;9:259–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoo HH, Yokozawa T, Satoh A, Kang KS, Kim HY. Effects of ginseng on the proliferation of human lung fibroblasts. Am J Chin Med. 2006;34:137–146. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X06003709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koo HN, Jeong HJ, Choi IY, An HJ, Moon PD, Kim SJ, Jee SY, Um JY, Hong SH, Shin SS, Yang DC, Seo YS, Kim HM. Mountain grown ginseng induces apoptosis in HL-60 cells and its mechanism has little relation with TNF-alpha production. Am J Chin Med. 2007;35:169–182. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X07004710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yun TK, Choi SY. Preventive effect of ginseng intake against various human cancers: a case-control study on 1987 pairs. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4:401–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yun TK, Choi SY. Non-organ specific cancer prevention of ginseng: a prospective study in Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:359–364. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee MC, Newman LA. Management of patients with locally advanced breast cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:379–398. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerber B, Scholz C, Reimer T, Briese V, Janni W. Complementary and alternative therapeutic approaches in patients with early breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;95:199–209. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9005-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehendale S, Aung H, Wang A, Yin JJ, Wang CZ, Xie JT, Yuan CS. American ginseng berry extract and ginsenoside Re attenuate cisplatin-induced kaolin intake in rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56:63–69. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0956-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aung HH, Mehendale SR, Wang CZ, Xie JT, McEntee E, Yuan CS. Cisplatin’s tumoricidal effect on human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells was not attenuated by American ginseng. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;59:369–374. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0278-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang CZ, Zhang B, Song WX, Wang A, Ni M, Luo X, Aung HH, Xie JT, Tong R, He TC, Yuan CS. Steamed American ginseng berry: ginsenoside analyses and anticancer activities. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54:9936–9942. doi: 10.1021/jf062467k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang CZ, Aung HH, Ni M, Wu JA, Tong R, Wicks S, He TC, Yuan CS. Red American ginseng: ginsenoside constituents and antiproliferative activities of heat-processed Panax quinquefolius roots. Planta Med. 2007;73:669–674. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-981524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rapaka RS, Coates PM. Dietary supplements and related products: a brief summary. Life Sci. 2006;78:2026–2032. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiPaola RS, Kuczynski WI, Onodera K, Ratajczak MZ, Hijiya N, Moore J, Gewirtz AM. Evidence for a functional kit receptor in melanoma, breast, and lung carcinoma cells. Cancer GeneTher. 1997;4:176–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fong HH, Pauli GF, Bolton JL, van Breemen RB, Banuvar S, Shulman L, Geller SE, Farnsworth NR. Evidence-based herbal medicine: challenges in efficacy and safety assessments. In: Leung P-C, Fong H, Xue CC, editors. Current Review of Chinese Medicine Annals of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Vol. 2. World Scientific; Singapore: 2006. pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Assinewe VA, Baum BR, Gagnon D, Arnason JT. Phytochemistry of wild populations of Panax quinquefolius L. (North American ginseng) J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:4549–4553. doi: 10.1021/jf030042h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed JC, Pellecchia M. Apoptosis-based therapies for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2005;106:408–418. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu WY, Guo HZ, Qu GQ, Han J, Guo DA. Mechanisms of pseudolaric Acid B-induced apoptosis in bel-7402 cell lines. Am J Chin Med. 2006;34:887–899. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X06004363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biliran H, Jr, Wang Y, Banerjee S, Xu H, Heng H, Thakur A, Bollig A, Sarkar FH, Liao JD. Overexpression of cyclin D1 promotes tumor cell growth and confers resistance to cisplatin-mediated apoptosis in an elastase-myc transgene-expressing pancreatic tumor cell line. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6075–6086. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]