Abstract

SSE1 and SSE2 encode the essential yeast members of the Hsp70-related Hsp110 molecular chaperone family. Both mammalian Hsp110 and the Sse proteins functionally interact with cognate cytosolic Hsp70s as nucleotide exchange factors. We demonstrate here that Sse1 forms high affinity (Kd~10−8 M) heterodimeric complexes with both yeast Ssa and mammalian Hsp70 chaperones, and that ATP binding to Sse1 is required for binding to Hsp70s. Sse1•Hsp70 heterodimerization confers resistance to exogenously added protease, indicative of conformational changes in Sse1 resulting in a more compact structure. The nucleotide binding domains of both Sse1/2 and the Hsp70s dictate interaction specificity, and are sufficient to mediate heterodimerization with no discernable contribution from the peptide binding domains. In support of a strongly conserved functional interaction between Hsp110 and Hsp70, Sse1 is shown to associate with and promote nucleotide exchange on human Hsp70. Nucleotide exchange activity by Sse1 is physiologically significant, as deletion of both SSE1 and the Ssa ATPase stimulatory protein YDJ1 is synthetically lethal. The Hsp110 family must therefore be considered an essential component of Hsp70 chaperone biology in the eukaryotic cell.

Molecular chaperones of the Hsp70 class are present in all cells and are essential for tolerance of protein denaturing stresses as well as protein biogenesis and regulation under normal growth conditions. Hsp70s share a common architecture defined by an amino-terminal nucleotide binding/ATPase domain (NBD) that regulates chaperone activity of a carboxyl-terminal peptide peptide binding domain (PBD). Hsp70 chaperones bind to exposed hydrophobic segments of proteins through the PBD, preventing their aggregation and assisting in folding to achieve native conformation. Hsp70 ATPase activity governs reversible transition between low- and high-affinity substrate binding states, and is in turn regulated by additional factors (reviewed in (1)). Hsp40-type, or J-domain co-chaperones stimulate ATP hydrolysis, and co-chaperones such as GrpE in bacteria and Fes1 in yeast accelerate release of nucleotide from Hsp70 (2-4). There is increasing evidence for collaboration of Hsp70s with co-chaperones that are themselves divergent Hsp70 homologs. For example, in the yeast endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the lumenal Hsp70, Kar2, binds the Grp170 subfamily homolog Lhs1, leading to reciprocal regulation of their respective ATPase activities (5). Similarly, Ssb ATPase activity is stimulated by a heterodimeric complex known as RAC (ribosome-associated complex) consisting of the Hsp70 Ssz1 and the Hsp40 Zuo1 (6, 7).

The Hsp110 subfamily of Hsp70-related chaperones is a poorly understood group defined by an extended linker region separating the ß and α subdomains of the PBD, as well as an extended carboxy terminus of unknown significance (8). Murine Hsp105α was shown to inhibit Hsp70-mediated refolding of a model substrate by inhibiting Hsp70 ATPase activity in vitro (9, 10). However, the molecular mechanism by which this inhibition occurs is unknown. In vivo, overexpression of Hsp110 confers increased thermotolerance in mammalian cell lines (11). In contrast to Hsp70, the Hsp110 class of chaperones appears incapable of mediating protein folding, confounding efforts to make predictions regarding their cellular roles (12, 13). Saccharomyces cerevisia epossesses two highly similar Hsp110 homologs encoded by the SSE1 and SSE2 genes. Cells lacking Sse1 are temperature sensitive and slow-growing, while loss of Sse2 has no obvious functional consequence (14, 15). We and others have demonstrated that deletion of both genes results in lethality, suggesting that Hsp110 chaperones play a critical role in cellular physiology (16-18). Sse1 is found in association with the two groups of cytosolic Hsp70 proteins Ssa and Ssb (19, 20). In addition, Sse1 stimulates the ATPase activity of Ssa1 in a synergistic manner with the Hsp40, Ydj1 (20). A functional role for this association is suggested by the finding that cells lacking Sse1 accumulate untranslocated α-factor, which is post-translationally inserted into the ER in an Ssa-dependent manner (20). Hsp110 and Sse have been recently shown to possess nucleotide exchange activity on their cognate Hsp70 partners, providing a functional role for this enigmatic class of chaperones (18, 21).

In this study, we show that in addition to the yeast Hsp70s Ssa and Ssb, Sse1 is able to form high affinity heterodimeric complexes with mammalian Hsc70 and Hsp70. These complexes are resistant to proteolytic attack, suggesting a compact structure. In contrast to a previous report, we find that ATP binding by Sse1 is absolutely required for complex formation with Hsp70 (18). Heterodimerization appears to be mediated by the respective NBDs with no discernable role played by the PBDs. Sse1 was found to possess potent Hsp70 nucleotide exchange activity for mammalian Hsp70, suggesting strict conservation of function along the eukaryotic lineage. Genetic data suggest that Sse1 and Ydj1 may operate with the Ssa proteins as an essential functional unit as sse1Δ ydj1Δ cells were found to be inviable while fes1Δ ydj1Δ mutants were not.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and plasmids

Yeast strains and plasmids are described in TABLE I. A plasmid-based fes1Δ::HIS3 disruption cassette was created by PCR amplification of fragments upstream and downstream of the FES1 open reading frame from BY4741 genomic DNA followed by cloning into a plasmid containing the HIS3 gene. The sse1::LEU2 plasmid-based knockout cassette was constructed in a similar manner. All knockouts were confirmed by PCR analysis.. To construct Sse1-Sse2 chimeras, p416GDP-FLAG-Sse1 and p416GPD-FLAG-Sse2 were used as templates for PCR reactions that altered codons 387 and 388 to a BamH I restriction site (Leu-Arg (Sse1) or Val-Arg (Sse2) to Gly-Ser). p416GPD-FES1 was constructed by PCR amplification of the ORF from genomic DNA incorporating flanking SpeI and XhoI sites for cloning into plasmid p416GPD. P416GPD-FLAG-Sse2 ATPase was constructed by PCR using p416GPD-Sse2 as a template and introducing a stop codon after codon 394. Sequences for primers used to make all constructs are available upon request.

TABLE I.

Plasmids and Strains

| Plasmid or strain | Description/genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| p416GPD-SSE1 | GPD-driven SSE1 | (16) |

| P416GPD-FES1 | GPD-driven FES1 | this study |

| p413GPD-FES1 | GPD-driven FES1 | this study |

| p416GPD-FLAG-SSE2 NBD | N-terminal FLAG tagged SSE2 ATPase domain (1-394) | this study |

| p416GPD-FLAG-SSE1 NBD | N-terminal FLAG tagged SSE1 ATPase domain (1-394) | (16) |

| p414TEF-SSE1 PBD | SSE1 C-terminal domain (residues 394-693) | (16) |

| p416TEF-FLAG-SSE1 | N-terminal FLAG tagged SSE1 | (16) |

| p416GPD-FLAG-E1A-E1P | SSE1, N-terminal FLAG tag | this study |

| p416GPD-FLAG-E1A-E2P | Chimera: SSE1 ATPase, SSE2 PBD, N-terminal FLAG tag | this study |

| p416GPD-FLAG-E2A-E2P | SSE2, N-terminal FLAG tag | this study |

| p416GPD-FLAG-E2A-E1P | Chimera: SSE2 ATPase, SSE1 PBD, N-terminal FLAG tag | this study |

| p416GPD-FLAG-SSE2 | N-terminal FLAG tagged SSE2 | this study |

| p413GPD-SSE1 | SSE1 ORF under GPD promoter control | this study |

| p413GPD-SSE2 | SSE2 ORF under GPD promoter control | this study |

| pYep24SSE1 | SSE1 full-length gene in pYEp24 vector backbone | (14) |

| pYep24SSE2 | SSE2 full-length gene in pYEp24 vector backbone | (14) |

| W303 | MATa ura3-52 trp1 leu2-3,112 his3-11,15 ade2-1 can1-100 | (35) |

| W303 sse1Δ | sse1Δ::kanMX | (34) |

| W303 sse1/2Δ | sse1Δ::kanMX sse2Δ::LEU2 | (17) |

| W303 ydj1-151 | ydj1-2::HIS3 LEU2::ydj1-151 | (36) |

| BY4741 | MATa his3Δ leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ | OpenBiosystems |

| BY4741 sse1Δ | sse1Δ::LEU2 | this study |

| BY4741 fes1Δ | fes1Δ::HIS3 | this study |

| BY4741 ydj1Δ | ydj1Δ::kanMX | OpenBiosystems |

| BY4741 ydj1Δ sse1Δ | ydj1Δ::kanMX sse1Δ::LEU2 | this study |

| BY4741 ydj1Δ fes1Δ | ydj1Δ::kanMX fes1Δ::HIS3 | this study |

| BY4741 sse1Δ fes1Δ | sse1Δ::LEU2 fes1Δ::HIS3 | this study |

Protein purification and complex assays

FLAG-Sse1, FLAG-Sse1K69Q, FLAG-Sse1G233D, FLAG-Ydj1 and Ssa1 were purified as described (20). Several different preparations of Hsp70 molecules were used for distinct purposes during the course of experiments. Purified human Hsp70 was kindly provided by D. Toft (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) and used for nucleotide exchange and protein refolding assays (22). Recombinant bHsc70ΔC and nucleotide binding domain (NBD) of bHsc70 were expressed and purified as described for use in native gel analysis and ATPase assays (23). Binding experiments were done by mixing proteins at the indicated concentrations in individual figure legends in 10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl and incubating at room temperature for 15 min. Reactions were then electrophoresed on 8-25% native polyacrylamide gels and stained with Coomassie blue. In experiments to determine the effects of nucleotides on heterodimer formation, binding reactions were supplemented with nucleotides at concentrations specified in figure legends. ADPBeFx, ADPAlFx, and ADPVi were prepared as described (24, 25). To determine Kd values, Coomassie stained gels of reactions carried out with constant amounts of Sse1 and varying amounts Ssa1 or bHsc70ΔC were scanned and digitized with a Molecular Imager GS-800 densitometer and ImageJ software. The fractions of free and bound Sse1 were then determined by reference to the intensity of an identical amount of Sse1 run alone on the same gel, and the apparent Kd at each bHsc70ΔC or Ssa1 concentration was then calculated explicitly using Origin software (Northampton, MA), assuming 1:1 stoichiometry for the complex.

Detection of ATP binding to chaperone complex

Varying concentrations (0.3 to 10 μM) of Sse1 were mixed with 0.03 μM [α–32P]-ATP either alone, or in the presence of excess (20 μM) bHsc70ΔC in 10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl. After a 15 min room temperature incubation, the reactions were resolved by native PAGE and the location of the radioactive ATP was visualized with a Molecular Dynamics Phosphorimager. Gels were subsequently stained with coomassie blue to identify the protein bands.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis

Immunoprecipitations of FLAG-Sse1, -Sse2, -Sse1/2 chimeras, and -Sse1/2 NBD fragments were performed as described (20). SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis were performed as described (16). Anti-Ssa1/2 and anti-Ssb polyclonal antibodies were used at 1:5000 dilution (generously provided by E. Craig). Anti-Sse1 polyclonal antibody was used at 1:2000 dilution (kindly provided by J. Brodsky, Univ. Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA). M2 monoclonal antibody (anti-FLAG, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used at 1:1000 dilution.

Protease protection experiments

1 μM Sse1 was treated with 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, or 32 μg/ml Proteinase K in either the presence of absence of 1 mM ATP or other nucleotides as indicated in individual figure legends, and with either 1 μM Hsc70ΔC, 1 μM NBD, or no added protein for 30 min. at room temperature in 10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM KCl. Reactions were terminated by addition of 1 mM PMSF, resolved by electrophoresis with 8-25% SDS PAGE, and stained with Coomassie blue.

Nucleotide exchange and ATPase assays

Nucleotide exchange assays were performed essentially as described (3). Briefly, Ssa- or human Hsp70-[α-32P]ATP complexes were formed by incubating 25 μg of the Hsp70 in complex buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 11 mM MgOAc, 25 mM ATP) and 100 mCi [α-32P]ATP (50 μL total volume) for 30 min on ice followed by passage through a G50 Microspin column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) prequilibrated with complex buffer. 6 μL of Hsp70-[α-32P]ATP complex was used per 50 μL exchange reaction, with or without Sse1 or mutant Sse1 (8 μg). 15 μL aliquots were removed at one, four, and seven minutes and immediately passed through a G50 Microspin column. 2 μL of eluate was spotted in duplicate on PEI- cellulose TLC plates and resolved in 1 M formic acid with 0.5 M LiCl. TLC plates were developed by phosphorimage analysis using a Storm 840 Imager and ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Single turnover ATPase assays were carried out by mixing 1 μM Hsc70, Hsc70ΔCterm, or NBD (with or without 1 μM 9 Sse1) with 0.03 μM Δ-32PATP (3000 Ci/mM) in 10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 5mM MgCl2, 25 mM KCl at r.t. At different times after mixing the ATP with the proteins, aliquots were taken and immediately mixed with an equal volume of 2% SDS, 50 mM EDTA to stop the reaction and subsequently resolved by TLC if formic acid/LiCl. Data were quantified with a Molecular Dynamics phosphorimager and fit to single exponential decays using Origin software to determine ATPase rates. Multiple turnover rates were done similarly except that cold ATP was added so that the total ATP concentration was 10 μM.

RESULTS

ATP binding by Sse1 is required to form a high affinity heterodimer with Hsp70

We and others have previously documented that Sse1 forms stable complexes with the yeast cytosolic Ssa and Ssb Hsp70 chaperone families (18-21). To quantitatively characterize the interaction between Hsp70 and Sse1 we utilized a mutant of bovine Hsc70 that is missing 10 kD from its C-terminus (bHsc70ΔC). This truncated version of Hsc70 has advantages over the full-length protein because it does not heterogeneously oligomerize on native gels, but is otherwise fully functional (26, 27). In addition, preparations of recombinant bHsc70ΔC purified from E. coli are free of detectable nucleotide, allowing us to measure the effects of added nucleotides on the interaction (28).

To determine the stoichiometry of the Sse1•Hsc70 complex, a constant amount of Sse1 was incubated with varying molar ratios of bHsc70ΔC in the presence of 1 mM ATP and the reactions were resolved on native polyacrylamide gels. At an Sse1:Hsc70 ratio of 2:1, roughly half of the Sse1 is observed to enter the complex while all of the added bHsc70ΔC becomes complexed (Figure 1A, lane 2). At a 1:1 ratio, both proteins are quantitatively incorporated into the complex and little of either protein is observed running free (Figure 1A, lane 3). Addition of bHsc70ΔC in excess of Sse1 resulted in increasing amounts of free bHsc70ΔC, but no apparent increase in the amount of complex present. We therefore conclude that Sse1 and bHsc70ΔC form a 1:1 complex. To assess the affinity of Sse1 for bHsc70ΔC, 0.25 μM Sse1 was incubated with 1 mM ATP and bHsc70ΔC at concentrations varying from 0 to 1 μM. Reactions were resolved on native gels, and free Sse1 was quantified by staining with Coomassie blue and densitometry (Figure 1B). Since neither protein was in large excess, the Kd was explicitly determined at each bHsc70ΔC concentration based on the fraction of free Sse1. A mean Kd of 61 nM ± 4 nM (s.d.) was obtained from experiments with five different bHscΔ70C concentrations. The Kd of Sse1 for yeast Ssa1 was determined similarly and was found to be slightly weaker at 490 nM ± 38 nM (s.d.), (data not shown), similar to that obtained by Raviol and coworkers (~ 150 nM). In addition, Sse1•bHsc70ΔC complex purified from mixed monomeric proteins by ultrafiltration exhibited 1:1 stoichiometry as assessed by SDS-PAGE and densitometry (see Figure S1). This stoichiometry is likely to extend to the native yeast Hsp70 chaperones Ssa and Ssb, based on previous findings (20, 21).

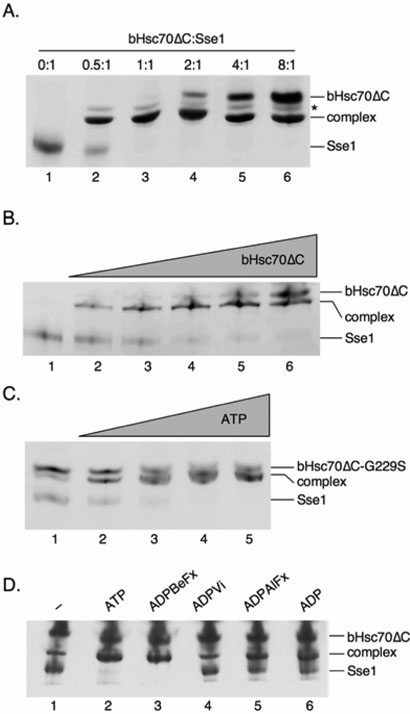

Figure 1. ATP binding by Sse1 is required to form a high affinity heterodimer with Hsp70.

A, Complex stoichiometry is 1:1. Native PAGE of 1 μM SSE1 incubated with 0 (lane 1), 0.5 (lane 2), 1 (lane 3), 2 (lane 4), 4 (lane 5), or 8 (lane 6) μM bHsc70ΔC in the presence of 1 mM ATP. The band marked with an asterisk is of unknown identity but only appears upon complex formation. B, Sse1 binds with high affinity to bHsc70ΔC. Native PAGE of 0.25 μM SSE1 incubated with 0 (lane 1), 0.063 (lane 2), 0.125 (lane 3), 0.25 (lane 4), 0.5 (lane 5), or 1 (lane 6) μM bHsc70ΔC in the presence of 1 mM ATP. C, Complex formation is ATP dependent. Native PAGE of 1 μM SSE1 with 2 μM bHsc70ΔC G229S and either 0 (lane 1), 0.6 (lane 2), 1.2 (lane 4), 2.4 (lane 5), or 4.8 (lane 6) μM ATP. D, The chemical state of the nucleotide modulates complex formation. Native PAGE of 1 μM SSE1 with 4 μM bHsc70ΔC in the presence of no nucleotide (lane 1), or 1 mM ATP (lane 2), ADPBeFx (lane 3), ADPVi (lane 4), ADPAlFx (lane 5), or ADP (lane 6).

We and others have demonstrated that mutant Sse1 that fails to bind ATP is incapable of associating with Ssa or Ssb in vivo (16, 20, 21). Consistent with this finding, we found that ATP addition is required to obtain quantitative association of Sse1 with bHsc70ΔC in vitro. To determine if this requirement reflects ATP binding to Sse1 or to bHsc70ΔC, we used a bHsc70ΔC variant protein containing a G229S mutation that greatly weakens its ATP binding (unpublished observations). In the absence of added ATP, only 20-25% of the Sse1 becomes complexed with bHsc70ΔC G229S, as shown in Figure 1C (lane 1). Addition of 0.6 μM ATP drives an increasing amount of Sse1 into the complex (lane 2), and addition of 1.2 (lane 3), 2.4 (lane 4), or 4.8 (lane 5) μM ATP quantitatively drives all of the Sse1 into the complex. Since the G229S bHsc70ΔC mutant does not bind ATP at these concentrations, we conclude that the effect of ATP on formation of the complex reflects binding to Sse1. The Sse1 concentration in this experiment is 1 μM and the observation that as little as 0.6 μM ATP supports complex formation indicates submicromolar affinity of Sse1 for ATP. We conclude that the interaction of Sse1 with ATP in the complex is of high affinity and that the nucleotide binding pocket of Sse1 must be occupied to allow heterodimerization with Hsp70 molecules.

To investigate the nucleotide dependency in more detail, we compared the efficacy of ATP, ADP, and the ground and transition state analogs ADPBeFx, ADPVi, and ADPAlFx in stimulating complex formation as assessed by native gel electrophoresis (Figure 1D). With no added nucleotide only 20% of the Sse1 becomes complexed (lane 1). Addition of 1 mM ATP caused all of the Sse1 to enter the complex (lane 2). ADP increased complex formation relative to no nucleotide but to a lesser extent than ATP (lane 6). This indicates that complex formation is more effectively supported by ATP than ADP. The effects of the ATP ground and transition state analogs are consistent with this conclusion. ADPBeFx best mimics the normal ATP (ground state) complex and supports complex formation as well as ATP (lane 3) (25). ADPVi is the best mimic of the transition state for phosphate ester bond cleavage and is ineffective in stimulating complex formation (lane 4), while ADPAlFx, which is a poorer mimic of the transition state, is more effective than ADPVi but less effective than either ATP or ADPBeFx at supporting complex formation (lane 5) (24, 25). This indicates not only that nucleotide is required to form the Sse1•bHsc70ΔC complex, but that the stability of this complex is modulated by the chemical state of the nucleotide.

To assess the persistence of the ATP interaction with the chaperone complex, we used [α–32P]-ATP and autoradiography to detect ATP binding to Sse1, bHsc70ΔC, and the bHsc70ΔC•Sse1 complex in native gels, as shown in Figure 2. Amounts of Sse1 ranging from 0.3 to 10 μM were mixed with limiting labeled ATP (0.03 μM) alone or in the presence of excess bHsc70ΔC (20 μM). Neither free Sse1 (Figure 2A) nor bHsc70ΔC (Figure 2B) was seen to effectively retain radioactive ATP during electrophoresis, but the bHsc70ΔC•Sse1 complex showed persistent association with ATP with a calculated Kd for ATP of 0.48 μM (Figure 2B). We next determined whether the ATP associated with the Sse1•bHsc70ΔC complex was stable or hydrolyzed over time. A two-fold excess of Sse1 (8 μM) was incubated with 4 μM bHsc70ΔC and sub-stoichiometric ATP (1 μM) and samples collected over time. In this reaction, nearly all the ATP should be bound to Sse1 within the heterodimeric complex, and as seen in Figure 2C, was hydrolyzed extremely slowly as assessed by thin layer chromatography. In contrast, the same conditions lacking Sse1 resulted in demonstrable hydrolysis by bHsc70ΔC. Taken together with previous genetic data, these findings suggest that Sse1 must bind ATP to effectively associate with Hsp70 molecules, and imply that these are highly stable complexes whose dissociation may be controlled by a nucleotide switch.

Figure 2. The Sse1•bHsc70ΔC heterodimer exhibits persistent association with ATP but hydrolyzes it slowly or not al all.

A, Sse1 alone does not retain ATP during electrophoresis. SSE1 at concentrations varying from 0.3 to 10 μM was incubated with 0.03 μM α32P-ATP in binding buffer and resolved by native PAGE. B, The Sse1:bHsc70ΔC complex shows persistent association with ATP during electrophoresis. Sse1 was mixed with radioactive ATP was in A, but with the addition of excess (20 mM) bHsc70ΔC. The excess, free bHsc70ΔC does not retain ATP during electrophoresis, but the complex of the two proteins retains the ATP during electrophoresis. C, ATP in the complex is hydrolyzed slowly or not at all. 1 μM ATP was mixed with 4 μM bHsc70DC in either the absence (“No Sse1”) or presence (“8 μM Sse1”) of Sse1 and hydrolysis of ATP was followed by TLC over time.

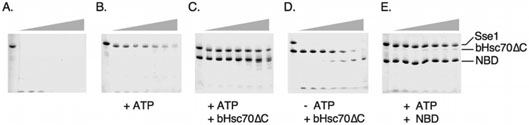

ATP and Hsp70 binding independently stabilize Sse1

Sse1 has been previously shown to produce proteolytic digestion fragments characteristic of other members of the Hsp70 superfamily (29). Moreover, ATP, but not ADP, binding reduces protease accessibility as shown by the accumulation of protease-resistant protein fragments, suggesting a conformational change upon nucleotide association (29). Given the high affinity of the Sse1•Hsp70 interaction, we reasoned that heterodimer formation might likewise stabilize one or both chaperones. To test this idea, a series of protease protection experiments using purified Sse1 and bHsc70ΔC were carried out. As shown in Figure 3A, very low levels of exogenously added proteinase K (0.5 μg/ml) were sufficient to degrade Sse1. Addition of 1 mM ATP decreased but did not block protease accessibility to Sse1 (Figure 3B). In contrast, the addition of bHsc70ΔC dramatically reduced proteolysis of Sse1 (Figure 3C). This protection absolutely required ATP for formation of the protein complex, as Sse1 was completely degraded in its absence and bHsc70ΔC cleaved to produce a band characteristic of the independently folded nucleotide binding domain (NBD) and additional lower molecular weight fragments (Figure 3D). The protease-resistant Sse1 produced by the addition of ATP or ATP and bHsc70ΔC migrated faster than non-treated Sse1. Based on mass spectrometric analysis, this molecule corresponds to Sse1 lacking approximately 25 amino acids (2-3 kD) from the highly charged carboxyl terminus, previously demonstrated to be dispensable for function (data not shown, (16)). We further tested the ability of the nucleotide analogs to afford protease protection to Sse1, and found a strong correlation with their ability to support complex formation. ATP, ADPBeFx and ADPAlFx all conferred protection, while ADP and ADPVi were only slightly more effective than no added nucleotide (Figure S2).

Figure 3. Sse1 and bHsp70ΔC form a protease-resistant complex.

The indicated purified proteins were incubated at a concentration of 10 μM with a series of increasing concentrations of exogenously added proteinase K (grey triangle) ranging from 0 to 16 μg/ml for 30 min and digestion reactions terminated by the addition of PMSF to 1 mM. Digestion products were resolved on a 8-25% SDS-PAGE gel and Coomassie-stained. A, Sse1 alone, B, Sse1 with 1 mM ATP, C, Sse1 and bHsc70ΔC with 1 mMM ATP, D, Sse1 and bHsc70ΔC with no ATP, E, Sse1 and the bHsc70 NBD with 1 mM ATP.

Determination of domains mediating Sse1•Ssa/Ssb interaction

To better understand the biochemical mechanism of Sse1•Hsp70 heterodimer function, we sought to determine the domains required for the interaction. We, and others, have previously observed that for unknown reasons, Sse2 inefficiently interacts with Ssb compared to Sse1 (data not shown, (19)). We sought to exploit this differential association to elucidate the domain(s) responsible for dictating binding specificity. We constructed and expressed in yeast FLAG-tagged chimeric proteins consisting of swapped Sse1 and Sse2 NBDs and PBDs and determined through coimmunoprecipitation analysis which chimera displayed reduced ability to bind Ssb. Interestingly, all chimeric constructs were functional as assessed by the ability to complement the slow growth of sse1Δ cells (Figure 4A). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that compensatory changes in gene expression account for the ability of the chimeras to function in vivo, Dragovic et al. have demonstrated that Sse2 possesses nucleotide exchange activity equivalent to Sse1 in vitro (21). As expected, both Ssa and Ssb co-purified with Sse1 (Figure 4B, E1-E1) while only Ssa efficiently copurified with Sse2 (Figure 4B, E2-E2) as indicated by Coomassie staining of the co-immunoprecipitation reactions. The chimera composed of an Sse1 NBD and an Sse2 PBD (E1-E2) associated with both Ssa and Ssb to levels indistinguishable from E1-E1. However, the chimera consisting of the Sse2 NBD and the PBD of Sse1 was unable to efficiently interact with Ssb. Antiserum directed against an epitope from the extreme C-terminus of Sse1 was used to confirm the identity of the chimeras (α-Sse1; (13)). These results, coupled with previous observations that the PBD of Sse1 expressed alone is unable to interact with Ssa and Ssb, indicate that the NBD is responsible for differential binding of Sse1 and Sse2 with Ssb (20).

Figure 4. The Sse NBD dictates binding specificity and is necessary and sufficient for interaction with Ssa.

A, Serial dilutions of sse1Δ cells expressing the indicated Sse1-Sse2 chimeras or empty vector were spotted onto plates and incubated at 30°C for 2 days. B, FLAG-tagged versions of the indicated Sse1-Sse2 chimeras (described in Experimental Procedures) were expressed in sse1Δ yeast and immunoprecipitated from protein extracts. Protein complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Coomassie staining or anti-Sse1 immunoblotting. C, sse1Δ cells expressing FLAG-Sse1 (lane 1), FLAG-Sse1 NBD (lanes 2 and 3), FLAG-Sse2 NBD (lanes 4 and 5) or Sse1 PBD (lanes 3 and 5) were subjected to FLAG immunoprecipitation. Protein complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie.

We showed previously that the Sse1 NBD was unstable in the absence of the PBD (16). This precluded us from determining if the Sse1 NBD was sufficient to interact with Ssa and Ssb. However, because Sse2 behaves differently than Sse1 with regard to the ability to interact with Ssb, we reasoned that the Sse2 NBD may not necessarily share this instability characteristic. We therefore expressed FLAG-tagged Sse2 NBD in cells lacking SSE1, followed by FLAG immunoprecipitation and Coomassie staining of the precipitated complexes. As previously documented, FLAG-Sse1 NBD could be immunoprecipitated and detected in cells expressing the Sse1 PBD in trans (Figure 4C, lane 3) but not from cells lacking the PBD (lane 2). In addition, Ssa and Ssb likewise co-immunoprecipitated with the Sse1 NBD and PBD. Surprisingly, the Sse2 NBD was stably produced and immunoprecipitated in the absence of either Sse PBD (lane 4). In addition, Ssa was efficiently copurified indicating that the Sse2 NBD is both necessary and sufficient for the interaction with Ssa. Stability of the Sse2 NBD was also moderately enhanced in the presence of the Sse1 PBD (lane 5), further evidence that the Sse PBD plays a stabilizing role for the NBD.

Sse1 interacts directly with the Hsp70 NBD to accelerate ATPase activity

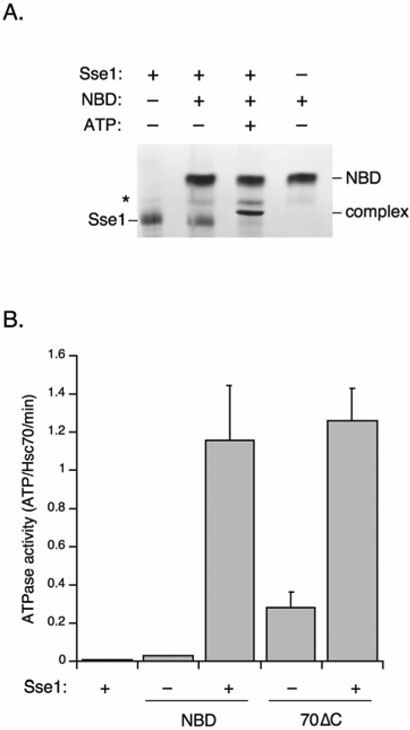

We next wished to determine which domain of Hsp70 serves as the primary docking site for Sse1. Because Sse1 activates Ssa1 ATPase activity in vitro, we hypothesized that the NBD would be the most likely point of interaction (18, 20). Purified bHsc70 NBD provided a level of protease protection for Sse1 indistinguishable from bHsc70ΔC, which in addition to the NBD contains the PBD but not the carboxyl terminal tail region (compare Figure 3E to 3C). To verify that this protection resulted from direct protein-protein interaction, we assessed the ability of the bHsc70 NBD to complex with Sse1 via native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. As shown in Figure 5A, addition of purified NBD failed to shift Sse1 in the absence of added nucleotide. Addition of ATP resulted in nearly 100% complex formation with available Sse1, in a manner very similar to the heterodimerization observed with bHsc70ΔC. A sub-stoichiometric band distinct from the Sse1•NBD complex was observed in the absence of ATP that persisted in the presence of nucleotide.

Figure 5. Sse1 directly binds the Hsp70 NBD to accelerate ATPase activity.

A, The indicated proteins at a concentration of 10 μM were combined in the presence or absence of 1 mM ATP and resolved using native PAGE as described in Experimental Procedures. NBD: bHsc70 nucleotide binding domain. B, Steady state ATPase rates for the bHsc70 NBD (NBD) or the bHsc70ΔC proteins (70ΔC) were determined in the absence or presence of equimolar Sse1 as described in Experimental Procedures.

To determine if Sse1 could stimulate ATPase activity via nucleotide exchange for bHsc70ΔC and the NBD, as it does with Ssa1, we carried out multiple turnover ATPase assays (20). In a single turnover ATPase assay in which [Hsp70]>[ATP], Sse1 does not stimulate the ATPase rate of Ssa1 (18). We similarly found that Sse1 will not stimulate the single-turnover ATPase rates of bHsc70ΔC or the NBD (data not shown). However, in multiple turnover assays in which [ATP]>[Hsp70], Sse1 will stimulate steady-state ATPase rates because it accelerates the otherwise slow exchange of ADP for ATP (18, 21). We found that purified bHsc70 NBD exhibited low ATPase activity in a multiple turnover assay, but that this rate was stimulated 40-fold by Sse1 (Figure 5B). Sse1 likewise stimulated the ATPase rate of bHsc70ΔC to a similar level, though in this case the ATPase rate of this enzyme in the absence of Sse1 is constitutively higher due to auto-activation caused by binding of its C-terminal tail in the peptide binding site of the PBD (23). Sse1 alone exhibited negligible ATPase activity. These data indicate that Sse1 can stimulate nucleotide release from bHsc70ΔC and the NBD alone, just as it does with a full length Hsc70. Taken together, these data indicate that the NBDs of bHsc70, and by extension endogenous yeast Ssa, constitute the main binding interface mediating functional dimerization with Hsp110 proteins.

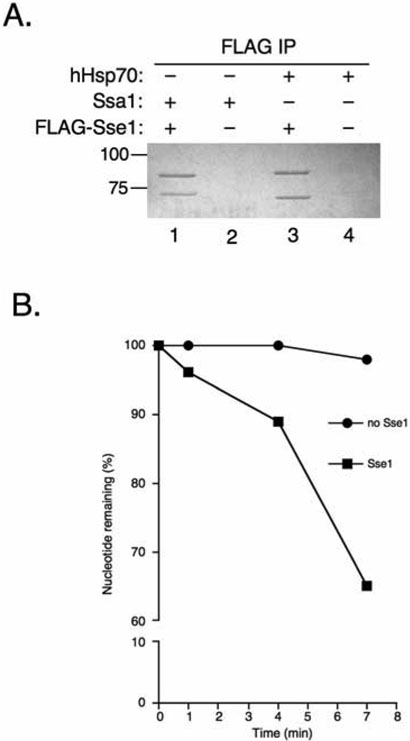

Sse1 is a general Hsp70 nucleotide exchange factor

Sse1 has been shown to stimulate the steady state ATPase activity of Ssa synergistically with Ydj1 in vitro (18, 20). Likewise, purified mammalian Hsp110 is a potent NEF for mammalian Hsp70 (21). Given the high affinity binding and ATPase stimulation of Sse1 with the mammalian Hsp70 variant bHsc70ΔC, we reasoned that the nucleotide exchange activity would likewise be conserved. To extend the relevance of this comparison beyond our truncated bovine Hsc70 variant, we obtained purified human Hsp70. As shown in Figure 6A, purified FLAG-Sse1 interacted with full-length human Hsp70 (hHsp70) in apparent 1:1 stoichiometry as judged by immunoprecipitation in the presence of excess hHsp70. Hsp70-[α-32P]ATP complexes were prepared and tested for nucleotide exchange activity. Addition of Sse1 led to loss of approximately 35% of pre-bound nucleotide after seven minutes of incubation compared to nearly 100% ATP remaining bound in the negative control (Figure 6B). These data suggest that Sse1 utilizes a binding interface conserved in both yeast and mammalian Hsp70 proteins, and that this interaction results in destabilization of the Hsp70 nucleotide binding pocket and subsequent exchange.

Figure 6. Sse1 binds and carries out nucleotide exchange on human Hsp70.

A, 20 μg FLAGSse1 (lanes 1 and 3) was added to 30 μg Ssa1 (lanes 1 and 2) or human Hsp70 (lanes 3 and 4) and subjected to FLAG immunoprecipitation followed by resolution on SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. B, Sse1 was added to [α-32P-ATP]-hHsp70 complexes and aliquots were removed at 1, 4, and 7 minutes, passed through a size exclusion column, and resolved by thin layer chromatography (TLC) to monitor exchange activity.

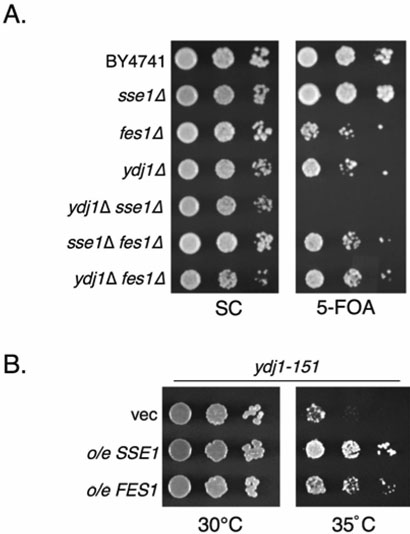

Interactions between SSE1 and SSA-modulating genes

Based on our biochemical data, we predicted that SSE1 may show synthetic interactions with genes encoding other modulators of Ssa activity. In support of this idea, deletion of SSE1 from yeast cells harboring the temperature sensitive ydj1-151allele was previously shown to result in enhanced temperature sensitivity (13). YDJ1 and FES1 encode the primary Ssa ATPase-stimulating and nucleotide exchange factors. Deletion of these genes or SSE1 results in a severe slow growth phenotype in many yeast strain backgrounds (3, 30). However we observed more moderate growth effects in the BY4741 strain used to create the yeast deletion library. Interestingly, in this background both fes1Δ and ydj1Δ mutants display more severe growth phenotypes than the SSE1 deletion. This may be in part due to the presence of SSE2, which provides minimal in vivo SSE protein function sufficient to allow survival relative to the sse1Δ sse2Δ combination, which is lethal (16-18). We therefore generated double mutant strains to test for synergistic phenotypes, including synthetic lethality. We transformed fes1Δ and ydj1Δ strains with a URA3-marked plasmid overexpressing SSE2, previously demonstrated to suppress phenotypes observed in sse1Δ cells (17). We then deleted SSE1 from these cells and tested for survival on growth medium containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA), which selects against Ura+ cells. Cells may grow under these conditions only upon loss of the URA3-marked plasmid. We found that while sse1Δ, fes1Δ and ydj1Δ cells all tolerated loss of SSE2, sse1Δ ydj1Δ double mutants were unable to do so (Figure 7A). In contrast, no synthetic effects were observed between SSE1 and FES1, or between FES1 and YDJ1. In addition, no synthetic effects were observed when cells were subjected to heat shock (37°C), suggesting that the presence of SSE2 is sufficient to confer viability under both normal and stress conditions. Goeckeler et. al, showed previously that SSE1 overexpression suppresses the temperature sensitivity of the ydj1-151 mutant. We reasoned that FES1 might likewise (13) suppress ydj1-151 if both proteins are functioning as Ssa nucleotide exchange factors. We found that overexpression of FES1 did indeed lead to partial suppression of ydj1-151 temperature sensitivity, albeit not as robustly as SSE1 (Figure 7B). Taken together, these results strongly support the hypothesis that Ssa, Sse1 and Ydj1 form a functional unit in the cytoplasm with Ydj1 stimulating Ssa ATPase activity, followed by Sse1 enhancing nucleotide exchange, thereby accelerating the chaperone cycle. Furthermore, Fes1 and Sse1 are likely both complementary, but non-redundant Ssa exchange factors, as Fes1 can functionally replace Sse1 and Sse2 only when substantially overexpressed ((18) and Figure S3). Lastly, the two Sse proteins may play a more dominant role than Fes1 in the cell, as judged by greater in vitro exchange activities, protein refolding enhancement and genetic interactions (18, 21).

Figure 7. Genetic interactions between SSE1 and the SSA1 modulators YDJ1 and FES1.

A, The indicated yeast strains were transformed with plasmids expressing either SSE2 (pYep24SSE2) or FES1 (p416GPD-FES1) and serial dilutions were plated on non-selective minimal medium or 5-FOA plates to select for loss of the covering plasmid. B, ydj1-151 yeast were transformed with plasmids overexpressing SSE1 (p416GPD-SSE1), FES1 (p416GPD-FES1) or with empty vector (vec, p416GPD) and serial dilutions were spotted onto plates and incubated at 30° or 35°C as indicated.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have biochemically characterized the requirements for function of the yeast Hsp110 Sse1 as a nucleotide exchange factor for the Hsp70 chaperone. In addition to the yeast Hsp70s, Ssa and Ssb, Sse1 was demonstrated to form high affinity complexes with mammalian Hsc70 (bHsc70ΔC) and Hsp70 (hHsp70). Complex formation required ATP binding by Sse1 with no discernable requirement for nucleotide binding by Hsp70. Interestingly, the interaction appears to be mediated by the respective NBDs with no discernable role played by the PBDs. Genetic evidence supports an in vivo role for Sse1 in a functional complex with Ssa and Ydj1, as an sse1Δ ydj1Δ strain was found to be inviable.

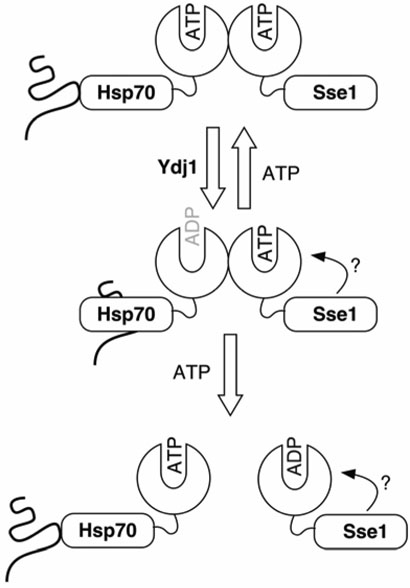

Our current model for Sse1•Hsp70 function is depicted in Figure 8 and is based on data from this and previous studies (16, 18-21). Sse1 must bind ATP to achieve high affinity (Kd ~ 10−8 M) binding to Hsp70, followed by activation of Hsp70 ATPase activity by Ydj1 resulting in nucleotide hydrolysis and subsequent tight binding of substrate. Sse1 then strips the nucleotide from Hsp70 locking it in a high affinity substrate binding conformation. In order to regenerate the ATP-bound form of Hsp70, we predict that the complex likely dissociates when the ATP bound to Sse1 is hydrolyzed or stripped by an unknown factor. Sse1 and mammalian Hsp110 have been demonstrated to possess weak ATPase activity (21, 29). ATP would subsequently reassociate with Hsp70, leading to release of substrate and completion of the chaperone cycle. This model clarifies a scheme recently put forward by Bukau and co-workers suggesting that ATP dissociates the Hsp110•Hsp70 heterodimer, with the status of the nucleotide binding pocket of Sse1 unknown (18). In that report, ATP was found to reduce Sse1 association with Ssa1 as determined by co-immunoprecipitation and surface plasmon resonance binding experiments. Several lines of evidence support our contention that ATP binding by Sse1 is required to support complex formation and nucleotide exchange activity. First, we have demonstrated that ATP is absolutely required for Sse1•Hsp70 (bHsc70ΔC) heterodimer formation in vitro as assessed by native PAGE and furthermore that ADP or transition state analogs are less effective. Second, addition of exogenous ATP was required for bHsc70ΔC or the bHsc70 NBD to confer protease resistance to Sse1. Third, the Sse1 G233D mutant that is incapable of binding ATP fails to associate with Ssa and Ssb in vivo and fails to promote nucleotide exchange in vitro (20, 21).

Figure 8. Model of Sse1-Hsp70 heterodimer function.

Based on data from this and previous studies we propose the following model: ATP bound-Sse1 initially forms a stable heterodimer with Hsp70. An Hsp40 (Ydj1 in yeast) stimulates hydrolysis of the ATP bound to Hsp70 leading to conformational change resulting in high affinity substrate binding. ADP is then released from Hsp70 by the nucleotide exchange activity of Sse1, causing Hsp70 to remain tightly associated with substrate until the nucleotide binding pocket is recharged with ATP, leading to a switch back to low affinity substrate binding. Subsequently, we predict that the weak ATPase activity of Sse1 results in dissociation of the complex. The role of the Sse1 PBD is unclear, but may involve association with the ATPase domain.

The roles of NEFs in Hsp70-mediated protein folding reactions are enigmatic. Dragovic and coworkers demonstrated that Sse1 dramatically increases both the rate and yield of the model substrate firefly luciferase in vitro and in vivo (21). In contrast, Raviol et al., found that Sse1 was not required for refolding of firefly luciferase, but was for bacterial luciferase in vivo. Fes1 was shown to be required for folding of both types of luciferase in vivo by the Bukau laboratory, while other reports found no stimulation in vitro (18, 21, 31). Furthermore, the human NEF HspBP1 inhibits refolding of firefly luciferase in vitro, as do the mouse Hsp110 homologs Hsp105α and Hsp105ß (10, 31). In addition, we show that that Sse1 inhibits the folding of chemically denatured ß-galactosidase when paired with hHsp70 and Ydj1 (Figure S4). The causes of these different results are not clear. One possibility is that subtle differences in experimental conditions, for instance nucleotide concentration or denaturation method, may confound the folding reactions. Differential substrate-dependent folding pathways may also contribute. Firefly luciferase is a multidomain monomeric protein, whereas bacterial luciferase and ß-galactosidase are multimeric enzymes. Carefully controlled analyses of the roles Hsp70 NEFs play in folding reactions with both model and native substrates will be required to separate potentially artifactual differences from authentic mechanistic ones. While the benefits of a profolding role are obvious, a case may be made for the utility of a folding-inhibitory role for Hsp110 proteins. For example, one of the few known cellular roles of Sse1 in yeast is in post-translational translocation of prepro-αF into the endoplasmic reticulum, a task that would require Hsp70 to remain bound to unfolded substrate until it is delivered to the translocation machinery (20). Intriguingly, the previously observed cytotoxicity caused by SSE1 overexpression could likewise be explained by the cellular Ssa pool being locked in nucleotide free, substrate bound complexes (16). This scenario is made plausible by the fact that the normal cellular ratio of Ssa:Sse1 is approximately 9:1, suggesting that the overwhelming majority of Ssa chaperones are not complexed with Sse1 (32). Given the strong binding affinity between Sse and Ssa proteins, tenfold SSE1 overexpression would likely result in quantitative association.

Major questions remain regarding Sse1 function in vivo. What are the cellular targets of the Sse1•Hsp70 heterodimers? Are Sse1•Hsp70 heterodimers and free Hsp70 differentially utilized in folding or translocation reactions? To date, Hsp70 chaperones in yeast are known to be involved in post-translational translocation events across organellar bounding membranes (Ssa), Hsp90 signal transduction activities (Ssa) and protein translation (Ssa and Ssb) (19, 33, 34). In addition, we, and others, have documented a requirement for Sse in regulation of protein kinase A signaling (15, 17). A complete understanding of the Hsp110 chaperone family will require applying the biochemical information obtained from in vitro studies using purified proteins to in vivo experiments with bona fide cellular substrates. For example, genetic and functional studies implicate Sse1 in Hsp90-mediated protein kinase maturation and transcription factor repression and activation (33, 34). The now-comprehensive identification of Sse1 as an Ssa nucleotide exchange factor should allow dissection of this important cellular role at the mechanistic level. Genome-wide functional screens for Sse1-dependent phenotypes should likewise yield insight into the breadth of processes requiring the Sse1•Hsp70 complex. In support of this concept, we have recently identified a role for Sse1 in signaling through the cell integrity MAP kinase signaling pathway (data not shown). Lastly, given the close functional relationship we have demonstrated between the Sse proteins and Fes1, and the potential contributions of another NEF, the Bag domain-containing Snl1, it will be of significant interest to dissect the division of labor between these factors with regard to modulation of cellular Hsp70 chaperone activity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Betty Craig, Jeff Brodsky, David Toft and Brian Freeman for invaluable advice and reagents. We also wish to thank Drs. Xiaohua Zeng, Jesus Eraso and Samuel Kaplan for their assistance with protein purification and continued support. We thank lab members for stimulating discussion.

This work was supported by Research Scholar Grant MBC-103134 and NIH grant GM074696 to K.A.M. and NIH grant G52522 and the Welch Foundation (AQ-148) to R.S.

ABBREVIATIONS

- HSP

heat shock protein

- NBD

nucleotide binding domain

- PBD

peptide binding domain

- NEF

nucleotide exchange factor

REFERENCES

- 1.Hartl FU, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: From nascent chain to folded protein. Science. 2002;295:1852–1858. doi: 10.1126/science.1068408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheetham ME, Caplan AJ. Structure, function and evolution of DnaJ: Conservation and adaptation of chaperone function. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1998;3:28–36. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1998)003<0028:sfaeod>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kabani M, Beckerich JM, Brodsky JL. Nucleotide exchange factor for the yeast Hsp70 molecular chaperone Ssa1p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:4677–4689. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4677-4689.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liberek K, Marszalek J, Ang D, Georgopoulos C, Zylicz M. Escherichia coli DnaJ and GrpE heat shock proteins jointly stimulate ATPase activity of DnaK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:2874–2878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steel GJ, Fullerton DM, Tyson JR, Stirling CJ. Coordinated activation of Hsp70 chaperones. Science. 2004;303:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1092287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang P, Gautschi M, Walter W, Rospert S, Craig EA. The Hsp70 Ssz1 modulates the function of the ribosome-associated J-protein Zuo1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:497–504. doi: 10.1038/nsmb942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hundley H, Eisenman H, Walter W, Evans T, Hotokezaka Y, Wiedmann M, Craig E. The in vivo function of the ribosome-associated Hsp70, Ssz1, does not require its putative peptide-binding domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:4203–4208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062048399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Easton DP, Kaneko Y, Subjeck JR. The Hsp110 and Grp170 stress proteins: Newly recognized relatives of the Hsp70s. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2000;5:276–290. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2000)005<0276:thagsp>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamagishi N, Ishihara K, Hatayama T. Hsp105α suppresses hsc70 chaperone activity by inhibiting Hsc70 ATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:41727–41733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407947200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamagishi N, Nishihori H, Ishihara K, Ohtsuka K, Hatayama T. Modulation of the chaperone activities of Hsc70/Hsp40 by Hsp105α and Hsp105β. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;272:850–855. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh HJ, Chen X, Subjeck JR. Hsp110 protects heat-denatured proteins and confers cellular thermoresistance. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31636–31640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh HJ, Easton D, Murawski M, Kaneko Y, Subjeck JR. The chaperoning activity of Hsp110. Identification of functional domains by use of targeted deletions. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:15712–15718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goeckeler JL, Stephens A, Lee P, Caplan AJ, Brodsky JL. Overexpression of yeast Hsp110 homolog Sse1p suppresses ydj1-151 thermosensitivity and restores Hsp90-dependent activity. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:2760–2770. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-04-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukai H, Kuno T, Tanaka H, Hirata D, Miyakawa T, Tanaka C. Isolation and characterization of SSE1 and SSE2, new members of the yeast Hsp70 multigene family. Gene. 1993;132:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90514-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirayama M, Kawakami K, Matsui Y, Tanaka K, Toh-e A. MSI3, a multicopy suppressor of mutants hyperactivated in the Ras-cAMP pathway, encodes a novel Hsp70 protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1993;240:323–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00280382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaner L, Trott A, Goeckeler JL, Brodsky JL, Morano KA. The function of the yeast molecular chaperone Sse1 is mechanistically distinct from the closely related Hsp70 family. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:21992–22001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313739200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trott A, Shaner L, Morano KA. The molecular chaperone Sse1 and the growth control protein kinase Sch9 collaborate to regulate protein kinase A activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2005;170:1009–1021. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.043109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raviol H, Sadlish H, Rodriguez F, Mayer MP, Bukau B. Chaperone network in the yeast cytosol: Hsp110 is revealed as an Hsp70 nucleotide exchange factor. EMBO J. 2006;25:2510–2518. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yam AY, Albanese V, Lin HT, Frydman J. Hsp110 cooperates with different cytosolic Hsp70 systems in a pathway for de novo folding. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:41252–41261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503615200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaner L, Wegele H, Buchner J, Morano KA. Theyeast Hsp110 Sse1 functionally interacts with the Hsp70 chaperones Ssa and Ssb. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:41262–41269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503614200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dragovic Z, Broadley SA, Shomura Y, Bracher A, Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones of the Hsp110 family act as nucleotide exchange factors of Hsp70s. EMBO J. 2006;25:2519–2528. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schumacher RJ, Hansen WJ, Freeman BC, Alnemri E, Litwack G, Toft DO. Cooperative action of Hsp70, Hsp90, and DnaJ proteins in protein renaturation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14889–14898. doi: 10.1021/bi961825h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang J, Lafer EM, Sousa R. Crystallization of a functionally intact Hsc70 chaperone. Acta Crystallograph. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2006;62:39–43. doi: 10.1107/S1744309105040303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith CA, Rayment I. X-ray structure of the magnesium(ii)•ADP•vanadate complex of the Dictyostelium discoideum myosin motor domain to 1.9A resolution. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5404–5417. doi: 10.1021/bi952633+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher AJ, Smith CA, Thoden JB, Smith R, Sutoh K, Holden HM, Rayment I. X-ray structures of the myosin motor domain of Dictyostelium discoideum complexed with MgADP•BeFx and MgADP•AlF4. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8960–8972. doi: 10.1021/bi00028a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ungewickell E, Ungewickell H, Holstein SE. Functional interaction of the auxilin J domain with the nucleotide- and substrate-binding modules of Hsc70. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:19594–19600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilbanks SM, Chen L, Tsuruta H, Hodgson KO, McKay DB. Solution small-angle X-ray scattering study of the molecular chaperone Hsc70 and its subfragments. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12095–12106. doi: 10.1021/bi00038a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang J, Prasad K, Lafer EM, Sousa R. Structural basis of interdomain communication in the Hsc70 chaperone. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:513–524. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raviol H, Bukau B, Mayer MP. Human and yeast Hsp110 chaperones exhibit functional differences. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caplan AJ, Douglas MG. Characterization of Ydj1: A yeast homologue of the bacterial DnaJ protein. J. Cell Biol. 1991;114:609–621. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.4.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabani M, McLellan C, Raynes DA, Guerriero V, Brodsky JL. HspBP1, a homologue of the yeast Fes1 and Sls1 proteins, is an Hsc70 nucleotide exchange factor. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:339–342. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O'Shea EK, Weissman JS. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee P, Shabbir A, Cardozo C, Caplan AJ. Sti1 and Cdc37 can stabilize Hsp90 in chaperone complexes with a protein kinase. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:1785–1792. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu XD, Morano KA, Thiele DJ. The yeast Hsp110 family member, Sse1, is an Hsp90 cochaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:26654–26660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothstein R. Targeting, disruption, replacement, and allele rescue: Integrative DNA transformation in yeast. In: Guthrie C, Fink G, editors. Methods in enzymology. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1991. pp. 281–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caplan AJ, Cyr DM, Douglas MG. Ydj1p facilitates polypeptide translocation across different intracellular membranes by a conserved mechanism. Cell. 1992;71:1143–1155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.