Abstract

Surface-functionalized nanoparticles enhance the rate of electron transfer (ET) between Cyt c(Fe2+) and Co(phen)33+ by a factor of 105 through simultaneous electrostatic binding of ET donor and acceptor.

Interprotein electron transfer (ET) is crucial to energy transduction in photosynthesis and respiration, and is a direct example of protein recognition coupled with chemistry. The effects of distance and driving force are well understood, and can be manipulated in synthetic and natural systems to enhance ET kinetics.1,2 In contrast, the effects of surface binding and dynamics on ET rates are harder to interpret,3-6 making new model systems crucial for understanding the role of dynamics in ET reactivity.

Nanoparticles are capable of catalyzing selected reactions, by acting as artificial receptors for substrates.7,8 For example, the rates of peptide ligation7 and phosphodiester cleavage were enhanced by up to 103–fold on functionalized nanoparticle surfaces.9 Here, we show a 105-fold enhancement of an intermolecular ET rate through use of surface-functionalized nanoparticles (Au-TX) as artificial receptors. This catalysis arises through bringing ET donor and acceptor into close proximity, demonstrating the ability to modulate protein ET at surfaces, and provides a tool for observing and controlling the interplay between binding, dynamics, and reactivity.

Bimolecular ET kinetics follow Marcus theory,2 with driving force, reorganization, and steric factors determining rate. Cytochrome c (Cyt c) undergoes rapid ET with other proteins, as well as with small molecules. The dominant ET pathway is over the exposed heme edge; however heme access is limited by surface Lys residues,10 making ET selective for partners that have the appropriate binding surface.

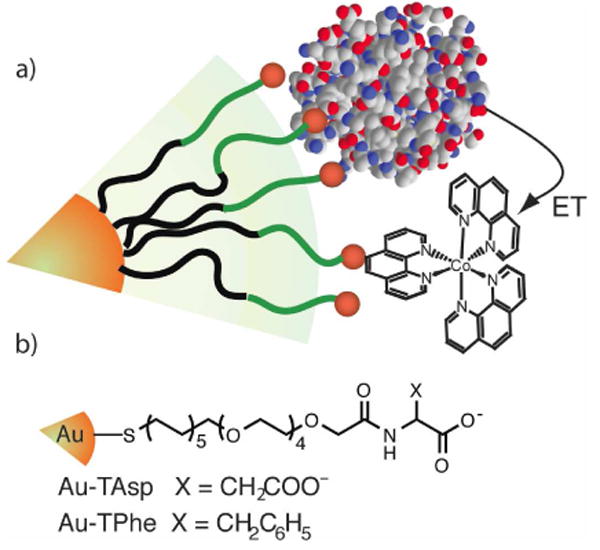

Au nanoparticles functionalized with thiol ligands containing the free-carboxylate form of amino acids (Au-TX)8 bind to Cyt c (pI = 10) with KS ∼ 107 M-1. 11,12 Moreover Au-TX binds selectively to the surface of Cyt c near the heme edge.11 As the charges of both Co(phen)33+ and Cyt c are complementary to that of Au-TX, we tested whether concurrent binding could catalyze ET. The kinetic scheme accounting for the pre-equilibrium binding of Cyt c to Au-TX, followed by Co(phen)33+ binding (KD) and ET (kET):

| (1) |

Cyt c was reduced with dithionite followed by gel filtration, and Co(phen)33+ synthesized as per the literature. Cyt c oxidation was monitored as a single exponential decrease in A550 following the mixing of Cyt c (5 μM after mixing, 10mM Tris, pH 7.40, I = 20 mM, 12 mM NaCl) with Co(phen)33+ (0.083 – 1.00 mM after mixing, in same buffer) in a stopped-flow spectrometer. Cyt c oxidation by Co(phen)33+ was nearly independent of [Co3+], with kET = 0.66 (±0.02) s-1 (Figure 2),13 in good agreement with prior reports.14 This has been attributed to a rate-limiting conformational change at the heme edge of Cyt c; however, under moderate ionic strength the bimolecular ET rate is kET/KD = 103 M-1 s-1.15

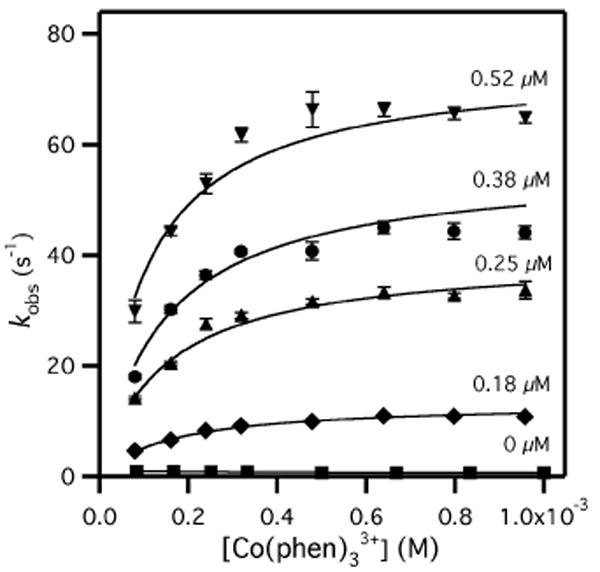

Figure 2.

Cyt c oxidation (5 μM) by Co(phen)33+ in the presence of varied Au-TAsp (0 – 0.52 μM); buffer is 10 mM Tris, pH 7.40, 12 mM NaCl, I = 20 mM, 25.0°C.

The Cyt c:Au-TAsp adduct was formed by pre-incubating Cyt c (10 μM) with Au-TAsp (0.16 – 1.04 μM; higher concentrations were not used due to high optical density), then mixing with Co(phen)33+ as above. Cyt c:Au-TAsp oxidation was evident as single-exponential decays in A550, indicating that Cyt c binding to Au-TAsp was in a rapid pre-equilibrium (Eq. 1). As the position of this equilibrium favored unbound Cyt c, the ET process may be considered as coupled.16 The observed rates for Cyt c:Au-TAsp exhibited saturation due to Co(phen)3+ binding, with kobs as high as 65 s-1 (Figure 2). Analogous data sets for Cyt c:Au-TPhe exhibited similar saturation kinetics.13 The second order kinetics were fitted to obtain apparent rate constants for Cyt c oxidation: kobs = kET(app)[Co]0/([Co]0+KD).

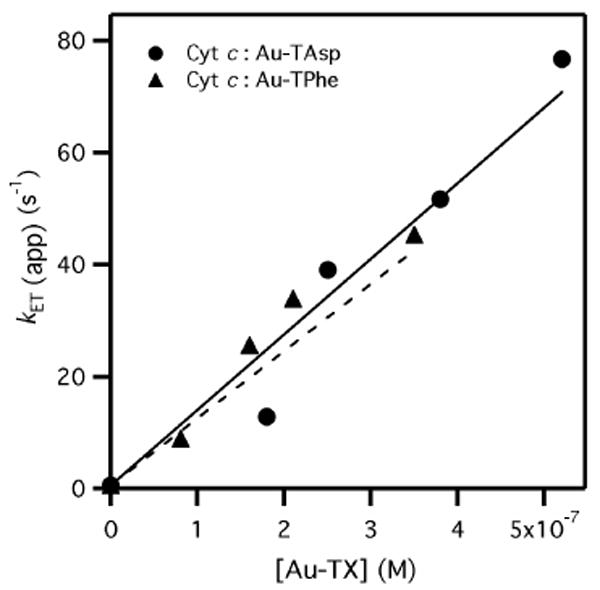

The apparent maximum ET rate, (kET)app, was a linear function of nanoparticle concentration, indicating that the binding of Cyt c to Au-TX (KS of Eq. 1) was far from equilibrium (Figure 3). Under rapid pre-equilibrium conditions, (kET/KS)[Au-TX] = (kET)app; the slope of Figure 3 is the absolute bimolecular rate constant for Co(phen)33+ reacting with Cyt c on the Au-TX surface. Linear least-squares fitting for Cyt c:Au-TX (X = Asp, Phe) yielded slopes that were nearly identical: kET/KS = 1.35 (±0.03) × 108 and 1.20 (±0.03) × 108 M-1 s-1, respectively. This is significantly larger than the ET rate in the absence of Au-TX (1 × 103 M-1 s-1),15 indicating that complexation by Au-TX catalyzed the ET reaction by 105.

Figure 3.

Bimolecular rate plot for Cyt c oxidation (5 μM, 10mM Tris, pH 7.4, I = 20 mM) by Co(phen)33+ in the presence of Au-TX (X = Asp, Phe). Linear fitting to (kET/KS)[Au-TX] = kET(app) yielded kET/KS = 1.35 (±0.03) × 108 (X = Asp) and 1.20 (±0.03) × 108 M-1 s-1 (X = Phe). Error bars are approximately the size of each data point.

This catalysis can be understood within the context of Marcus theory,2 which states that the rate of bimolecular ET depends on the collision rate (Z ∼ 1 × 1011 M-1 s-1) and the activation energy (ΔG*): k = Zexp(-ΔG*/RT). In the limit of low driving force (ΔG0 ≪ λ), ΔG* = λ/4 + w, where w is the work to bring the reactants together. The reaction of Cyt c(Fe2+) with Co(phen)33+ (k = 1 × 103 M-1 s-1) can be attributed to λ = 44 kcal/mol, assuming that w = 0. This λ is consistent with the self-exchange reaction rate for each reagent.2 The faster rate in the presence of Au-TX may arise from changes in either λ or w; should λ remain unchanged, the data could be accommodated with w = - 7 kcal/mol. This value for work is attributed to the electrostatic attraction of Co(phen)33+ and Cyt c to Au-TX.

This electrostatic attraction increases the local concentration of each reagent. Calorimetric and kinetic data indicate that the Co(phen)33+:Au-TX binding equilibrium was saturated at 1 mM [Co(phen)33+], leading to the plateau in kobs (Figure 2); in contrast, Cyt c binding to Au-TX was sub-saturating, leading to the linear dependence of kET on [Au-TX] (Figure 3). Entropic factors (i.e. the “Circe effect”17) presumably dominate intermolecular ET catalysis in the Cyt c:Au-TX system, however enthalpic contributions cannot be excluded.

Kinetic complexity masked the rate of electron flow within encounter complexes in previous studies of the relationship between conformational dynamics and interprotein ET. In some cases, the overall rate was limited by a conformational change, leading to gated ET.16,18,19 In other cases, ET was rate-limiting but occurred following a disfavored conformational change with concomitant coupled ET.3,4 Although amide H/D exchange showed that Au-TPhe bound to a smaller Cyt c face than Au-TAsp,11 which could increase the rate of conformational dynamics, this did not translate into faster ET kinetics for Cyt c:Au-TPhe. This suggests that conformational dynamics within the {Cyt c:Au-TX:Co3+} encounter complex are much faster than ET, and that dynamics may be uncoupled from ET under these conditions.

In summary, we have demonstrated the use of nanoparticles as highly efficient catalysts for intermolecular ET. These catalysts function by reversibly binding the ET donor and acceptor, thus increasing the local concentration of the redox partners. This process may provide a model for understanding intermolecular ET, in which binding is coupled to reactivity.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

a) Encounter complex for election transfer from Cyt c to Co(phen)33+ on the surface of Au-TX; b) structure of TX ligands.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Graduate Council for a fellowship (HB), the NIH (GM077413, MJK; GM077173, VMR) for funding, and Prof. M. Maroney for instrument access.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Additional kinetics and calorimetric data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Gray HB, Winkler JR. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:537–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcus RA, Sutin N. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;811:265–322. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang SA, Crane BR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15465–15470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505176102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang ZX, Kurnikov IV, Nocek JM, Mauk AG, Beratan DN, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2785–2798. doi: 10.1021/ja038163l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Groves JT, Fate GD, Lahiri J. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:5477–5478. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu T, Zhong J, Gan X, Fan CH, Li GX, Matsuda N. ChemPhysChem. 2003;4:1364–1366. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200300817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fillon Y, Verma A, Ghosh P, Ernenwein D, Rotello VM, Chmielewski J. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6676–6677. doi: 10.1021/ja070301+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.You CC, De M, Han G, Rotello VM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12873–12881. doi: 10.1021/ja0512881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manea F, Houillon FB, Pasquato L, Scrimin P. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2004;43:6165–6169. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cytochrome c. Univ Sci Books; Sausalito, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayraktar H, You CC, Rotello VM, Knapp MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2732–2733. doi: 10.1021/ja067497i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marini MA, Marti GE, Berger RL, Martin CJ. Biopolymers. 1980;19:885–898. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Supplemental Material

- 14.Rush JD, Koppenol WH, Garber EAE, Margoliash E. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:7514–7520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holwerda RA, Knaff DB, Gray HB, Clemmer JD, Crowley R, Smith JM, Mauk AG. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:1142–1146. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson VL. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:87–93. doi: 10.1021/ar9900616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jencks WP. In: Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. Meister A, editor. Vol. 43. John Wiley & Sons; 1975. pp. 219–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mei HK, Wang KF, Peffer N, Weatherly G, Cohen DS, Miller M, Pielak G, Durham B, Millett F. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6846–6854. doi: 10.1021/bi983002t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pletneva EV, Fulton DB, Kohzuma T, Kostic NM. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:1034–1046. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.