Abstract

The assembly of collagen fibers, the major component of the extracellular matrix (ECM), governs a variety of physiological processes. Collagen fibrillogenesis is a tightly controlled process in which several factors including collagen binding proteins play a crucial role. Discoidin domain receptors (DDR1 and DDR2) are receptor tyrosine kinases that bind to and get phosphorylated upon collagen binding. The phosphorylation of DDRs is known to activate matrix metalloproteases, which in turn cleave the ECM. In our earlier studies, we established a novel mechanism of collagen regulation by DDRs, that is, the extracellular domain (ECD) of DDR2, when used as a purified, soluble protein, inhibits collagen fibrillogenesis in-vitro. To extend this novel observation, the current study investigates how the DDR2-ECD, when expressed as a membrane anchored, cell-surface protein, affects collagen fibrillogenesis by cells. We generated a mouse osteoblast cell line which stably expresses a kinase deficient form of DDR2, termed DDR2/-KD, on its cell surface. Transmission electron microscopy, fluorescence microscopy and hydroxyproline assays demonstrated that the expression of DDR2/-KD not only reduced the rate and abundance of collagen deposition but also induced significant morphological changes in the resulting fibers. Taken together, our observations extend the functional roles that DDR2 and possibly other membrane anchored collagen binding proteins can play in the regulation of cell adhesion, migration, proliferation and in the remodeling of the extracellular matrix.

Abbreviations: DDR2, ECD, KD, HP, MMP, TEM, vWF

Introduction

Collagen type I in its mature fibrillar state is the major component of the extra cellular matrix (ECM) in most mammalian tissues1. Collagen fibers not only impart mechanical strength to the tissue but also interact with cells through cell surface receptors and soluble proteins, which is integral to cell proliferation, migration, survival, attachment and cellular differentiation. The assembly of collagen fibers (fibrillogenesis) is a complex process regulated in part by a variety of collagen-binding proteins and other molecules which may directly or indirectly interact with the collagen molecules and fibrils. Several collagen binding proteins such as decorin2, lumican2, cartilage oligomeric matrix protein3, fibromodulin4, SPARC5 and matrilin6 etc. have been shown to influence collagen fibrillogenesis. However, almost all these proteins occur as cell-secreted, soluble proteins in the ECM. It is not well-understood to what extent collagen-binding proteins when anchored to the cell-surface affect the assembly of collagen fibrils in the ECM.

The collagen-binding membrane proteins, Discoidin Domain Receptors (DDR1 and DDR2) belong to the family of receptor tyrosine kinase and are expressed in a variety of mammalian cells7, 8. These transmembrane glycoproteins (MW~ 125kD) have been found to be overexpressed or atypically expressed in several malignancies9–12 and regulated in diseases such as atherosclerosis13, lymphangioleio-myomatosis14, rheumatoid arthritis15 and osteoarthritis16. DDRs are characterized by three distinct regions17: an extracellular domain (ECD) which is responsible for collagen-binding, a transmembrane region and an intracellular kinase domain. Binding of collagen(s) to the DDR ECD, is known to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of the DDR kinase domain7, 8; prolonged activation of the DDR kinase domain results in upregulation or activation of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs 1, 2, 9 and 13) which cleave and degrade the collagen fibers in the ECM7, 14, 16.

A second mode of collagen regulation previously reported by our laboratory shows that the ECD of DDR1 or DDR2 when expressed as a soluble protein can modulate fibrillogenesis of collagen type 1 in-vitro18, 19. In particular, we had found that DDR2 ECD delays collagen fibrillogenesis and the collagen fibers formed in the presence of DDR2 ECD were thinner and lacked the native D-periodic banded structure. However, these earlier observations were mainly based on using purified collagen and a soluble form of DDR2 ECD, whereas thus far the DDR2 ECD has only been reported as an integral component of the membrane anchored full-length DDR2 receptor.

Therefore in this study we aimed to investigate if the expression of DDR2 ECD anchored to the cell-surface preserves the capacity to modulate collagen fibrillogenesis for collagen endogenously secreted by the cells. To address this question we created stably transfected mouse osteoblast cell lines to express a DDR2 isoform, named DDR2/-KD, which resembles the naturally occurring full-length DDR2 except that it lacks the kinase domain. We could thus ensure that our observed effects on collagen morphology and structure would be due only to DDR2 ECD interaction and not through the cleaving action of MMPs, known to be activated upon DDR2 kinase domain activation. Since mouse osteoblasts endogenously secrete collagen, we were able to examine the effects of DDR2/-KD expression on collagen morphology and deposition in the ECM by using techniques such as transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and hydroxyproline (HP) assay. We elucidate how the cell-surface expression of DDR2 ECD plays a major role in regulating the rate of collagen fibrillogenesis and morphology of collagen fibers. Our results not only demonstrate a novel mechanism of collagen regulation by DDRs but also signify the importance of cell-surface anchored collagen binding proteins in regulating collagen fibrillogenesis.

Results

Characterization of DDR2/-KD and stable cell lines

To evaluate the changes in ECM induced by expression of DDR2/-KD, we utilized mouse osteoblasts cells (MC3T3, E1 subgroup-4 clone), which are known to endogenously secrete collagen and generate well defined collagen fibers in their ECM. These cells were previously utilized to demonstrate that overexpression of lysyl hydroxylase-2b leads to defective collagen fibrillogenesis20. Collagen assembly in the ECM of these cells takes one to several weeks, therefore, it was necessary to stably transfect these cells with DDR2/-KD to observe its effect on collagen fibrillogenesis.

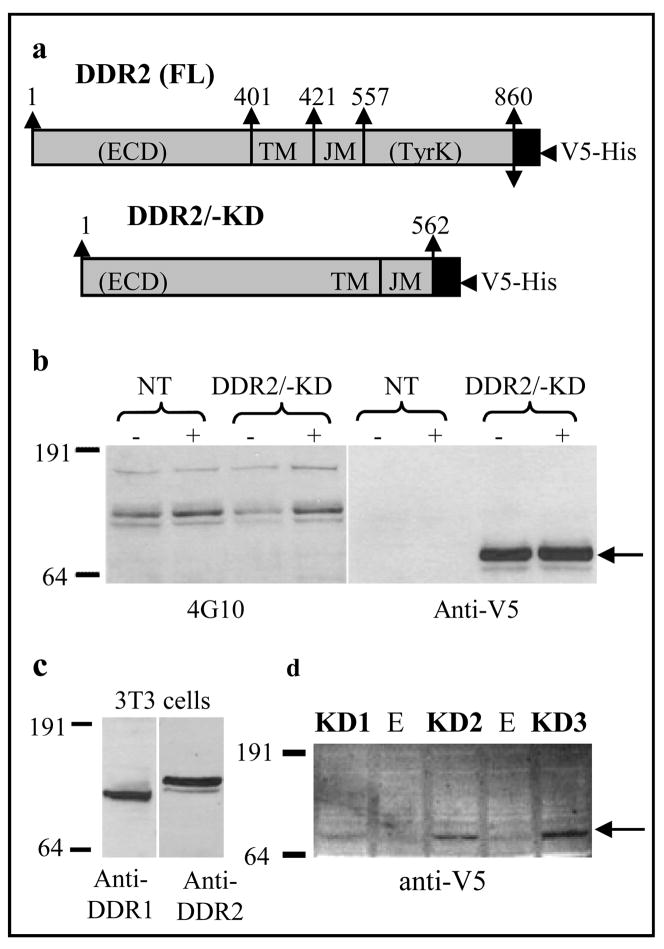

Figure 1a shows a schematic representation of the DDR2/-KD construct, which leads to the expression of a truncated DDR2 protein, preserving the extracellular, transmembrane and juxtamembrane regions but lacking the kinase domain. This DDR2/-KD construct is tagged with a V5 and multi-His epitope at its C-terminus. To verify that the DDR2/-KD proteins do not undergo collagen induced tyrosine phosphorylation, HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected with DDR2/-KD, stimulated with collagen and analyzed using SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. HEK 293 cells, which have an endogenous population of DDR1 and DDR2 (data not shown), show a collagen induced phosphorylation signal around a MW of 125kD. No phosphorylation bands were detected for DDR2/-KD protein (expressed ~70 kDa, indicated by arrow), consistent with the removal of the kinase domain. Additionally, expression of DDR2/-KD did not inhibit the collagen-induced phosphorylation of endogenously expressed DDRs (~ 125kD). Similar results were obtained using MC3T3 cells showing no phosphorylation for the DDR2/-KD protein (data not shown). Figure 1c shows endogenous expression of DDR1 and DDR2 in MC3T3 cells around 125kD. Figure 1d shows the expression of DDR2/-KD in three stable cell clones, KD1, KD2 and KD3 which were selected for further studies based on their increasing levels of expression of the DDR2/-KD protein.

Figure 1.

Creation of stable cells lines expressing the recombinant protein DDR2/-KD. a) A schematic representation of V5 His-tagged full-length mouse DDR2 and of the V5 His-tagged membrane anchored, kinase deficient DDR2 (DDR2/-KD) transmembrane protein. The extracellular (ECD), transmembrane (TM), juxtamembrane (JM) and tyrosine kinase (TyrK) domains are indicated. The numbers denote the sequence of amino acids in our recombinant proteins. b) DDR2/-KD does not undergo collagen induced tyrosine phosphorylation. Following SDS-PAGE, Western blot of whole cell lysates from native (NT) or transiently transfected (DDR2/-KD) HEK293 cells before (−) and after (+) collagen stimulation, were probed using anti-phosphotyrosine (4G10) or anti-V5 antibodies. While the ~ 125kD band indicates phosphorylation of endogenously occurring DDRs, no phosphorylation signal was present for DDR2/-KD (indicated by arrow). c) Western blot indicating expression of endogenous DDR1 and DDR2 in 3T3 cells. d) Three stable MC3T3 cell lines, KD1, KD2 and KD3 were selected for our study, which show increasing levels of DDR2/-KD expression (arrow). (E) indicates empty lane.

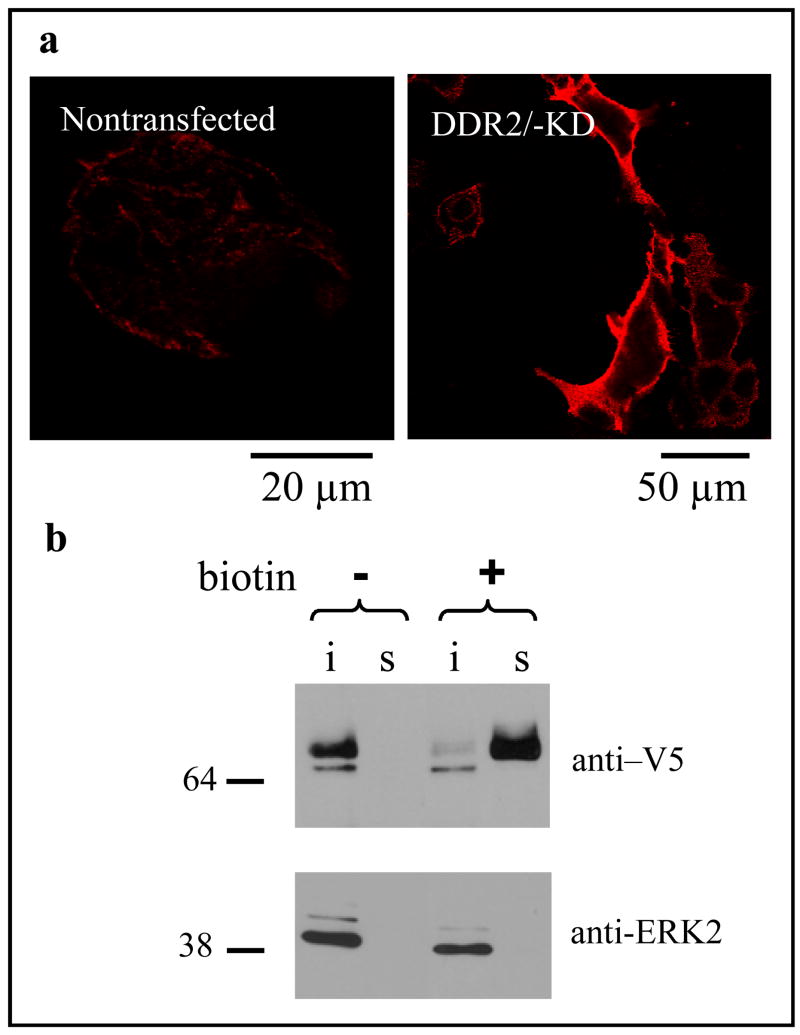

Membrane localization of DDR2/-KD was verified using immunocytochemistry followed by confocal microscopy on samples of HEK 293 cells transiently transfected with DDR2/-KD (figure 2a). To assess the membrane localization of DDR2/-KD on MC3T3 cells, which are very thinly spread and thus not amenable to confocal microscopy, we carried out cell-surface biotinylation assays. As shown in figure 2b, almost the entire fraction of DDR2/-KD was localized on the cell membrane.

Figure 2.

DDR2/-KD is localized on the plasma membrane. a) Confocal images of HEK293 cells transiently transfected with DDR2/-KD and immunolabeled with an antibody against the DDR2 ECD; nontransfected cells show a low level of endogenous DDR2 while transfected cells show an increased level of DDR2 ECD on the membrane. b) Cell surface biotinylation of MC3T3 cells expressing DDR2/-KD construct, demonstrating surface localization of the truncated receptor. Cell samples were biotinylated (as indicated) and surface proteins were precipitated from the lysates with streptavidin-agarose beads (s lanes); the supernatant from the pull-down was recovered and probed for intracellular proteins (i lanes). Following SDS-PAGE, samples were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against V5 tag (DDR2/-KD) or ERK2 as indicated. DDR2/-KD is mainly present on the cell surface, while a lower molecular weight band (probably indicating the immature, non glycosylated receptor) is only found in the intracellular lane. The intracellular protein ERK2 is only present in the intracellular lane, demonstrating that biotinylation is specific to cell surface proteins. As an additional control, non-biotinylated samples, show that the streptavidin pull down is specific to biotinylated proteins.

DDR2/-KD alters collagen fiber morphology

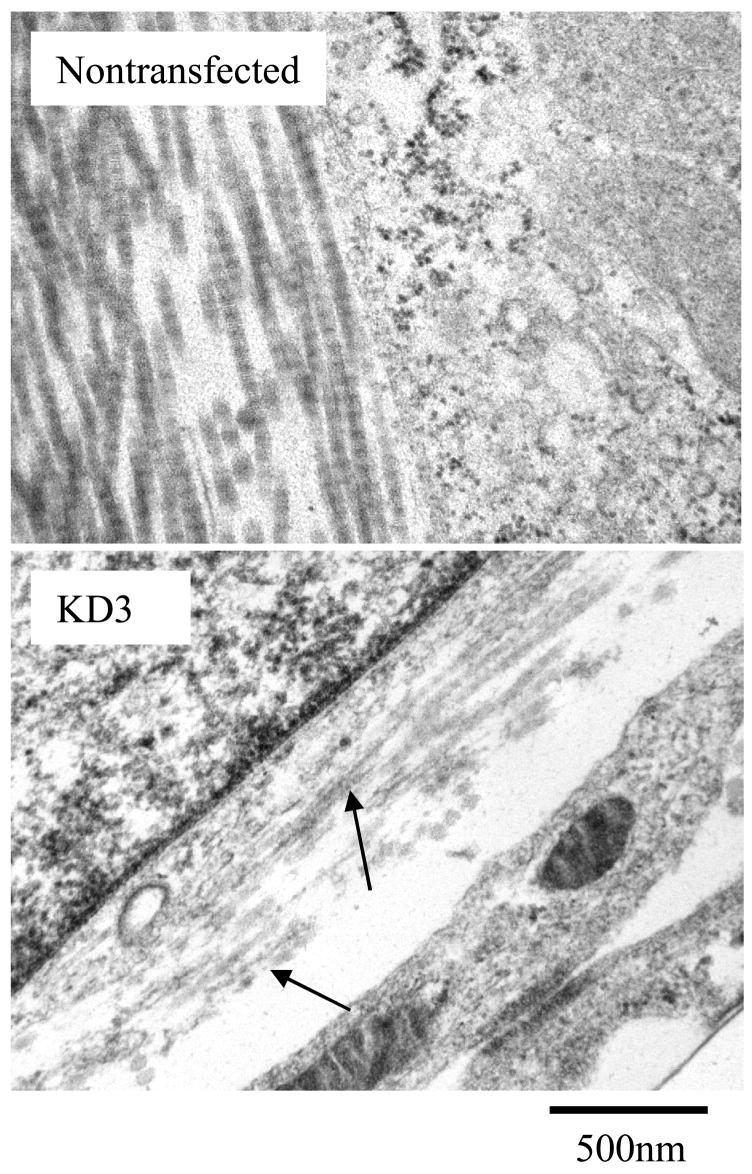

To analyze if the expression of DDR2/-KD affects the ultra-structural morphology of collagen fibers assembled in the ECM, we employed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) on samples of native and stable cell lines. As shown in figure 3, native cells showed occurrence of well-formed collagen fibers in the ECM with the characteristic D-periodic banded structure, as early as after one week of culture and for all later time points. In contrast, all three clones of DDR2/-KD lacked the typical collagen banding pattern for all time points examined (weeks 1, 2 and 3). Fibers with intact native banded structure were only occasionally observed in the DDR2/-KD cell lines.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of DDR2/-KD inhibits native banded structure of collagen fibers. Representative TEM micrographs show collagen fibers in the ECM. The native nontransfected cells show well formed collagen fibers with banded structure. In contrast, stable cell lines expressing DDR2/-KD were comprised of collagen fibers with weak or no banded structure; arrows indicate fibers with poor banded structure. All samples shown were cultured for two weeks.

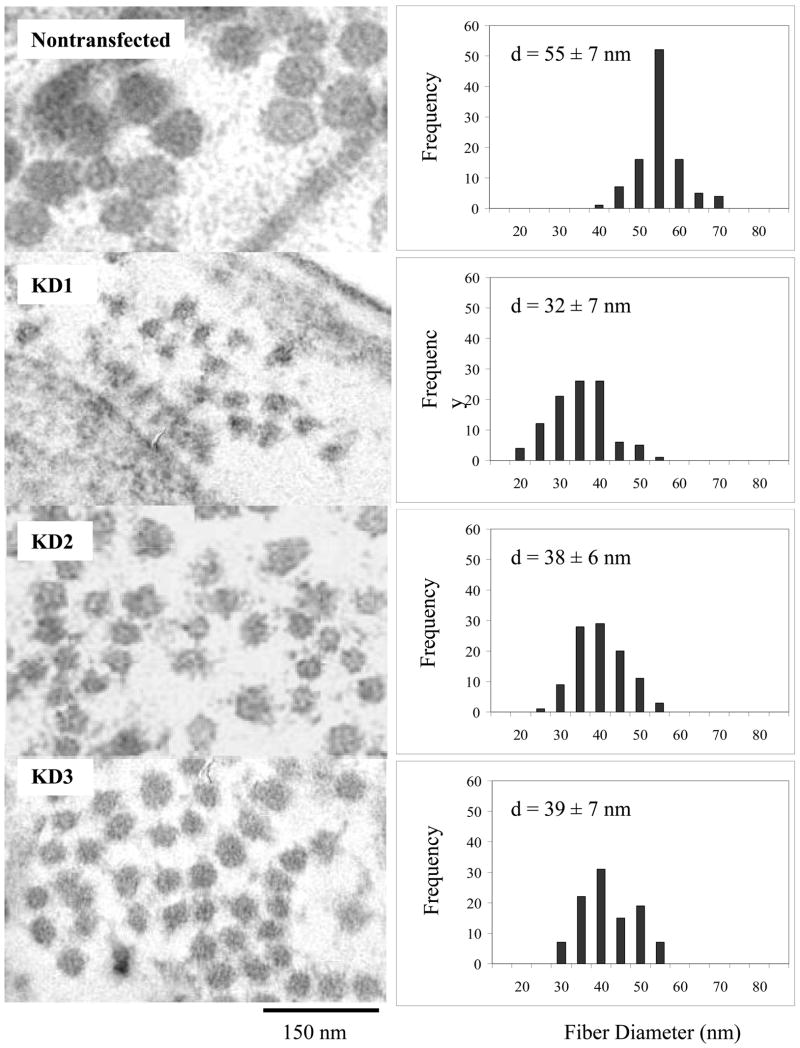

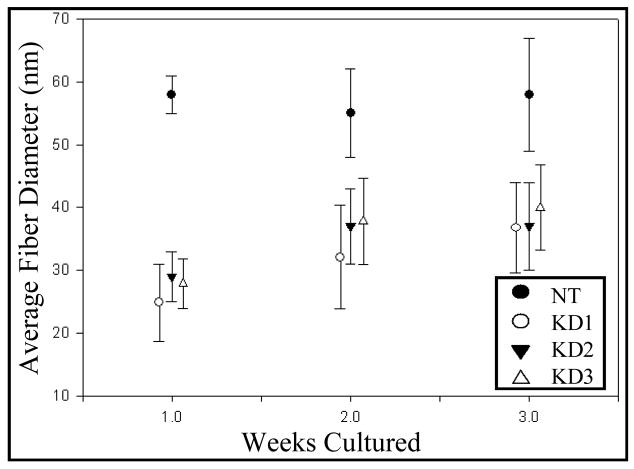

Next, we examined if expression of DDR2/-KD results in changes in the collagen fiber diameters present in the ECM. Figure 4 shows a frequency distribution of collagen fiber diameter for 100 fibers for each sample at two weeks of culture. A striking reduction in the average fiber diameter was observed for DDR2/-KD expressing cells as compared to native cells. However, no significant change in the average fiber diameter was observed between the different DDR2/-KD clones. To investigate if the expression of DDR2/-KD affects the rate of lateral growth of collagen fibers, we ascertained the average fiber-diameter as a function of time for native and the DDR2/-KD clones. As shown in figure 5, the native cells exhibited almost no increase in fiber diameter over a period of 1 to 3 weeks. The DDR2/-KD samples, in contrast, showed an increase in fiber growth over the first two weeks with little increase in fiber diameter thereafter. The average fiber diameter for all DDR2/-KD samples was significantly lower than that of native cells at each time point. These observations indicate that while the collagen fibers in native cells had reached their steady-state diameter after one week, the collagen fibers in DDR2/-KD display a slower lateral growth rate and approach their steady-state diameters at a later stage.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of DDR2/-KD affects collagen fiber diameter. The collagen fiber diameters for all three stable cell lines expressing DDR2/-KD are significantly smaller than nontransfected cells. In the histogram plots, ‘d’ is the average fiber diameter obtained by measuring 100 fibers for each cell line. The TEM images and measurements shown here were performed on cells cultured for two weeks.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of DDR2/-KD affects collagen fiber diameter growth rate. The lateral growth of collagen fibers in native cells reaches a steady state value for fiber diameter within one week. Cells expressing DDR2/-KD not only have smaller fiber diameters at each time point, but also continue to grow laterally for 1 to 2 weeks of culture. Our results indicate that cells expressing DDR2/-KD reach a steady state value for lateral growth later than native cells.

DDR2/-KD delays rate of collagen fibrillogenesis

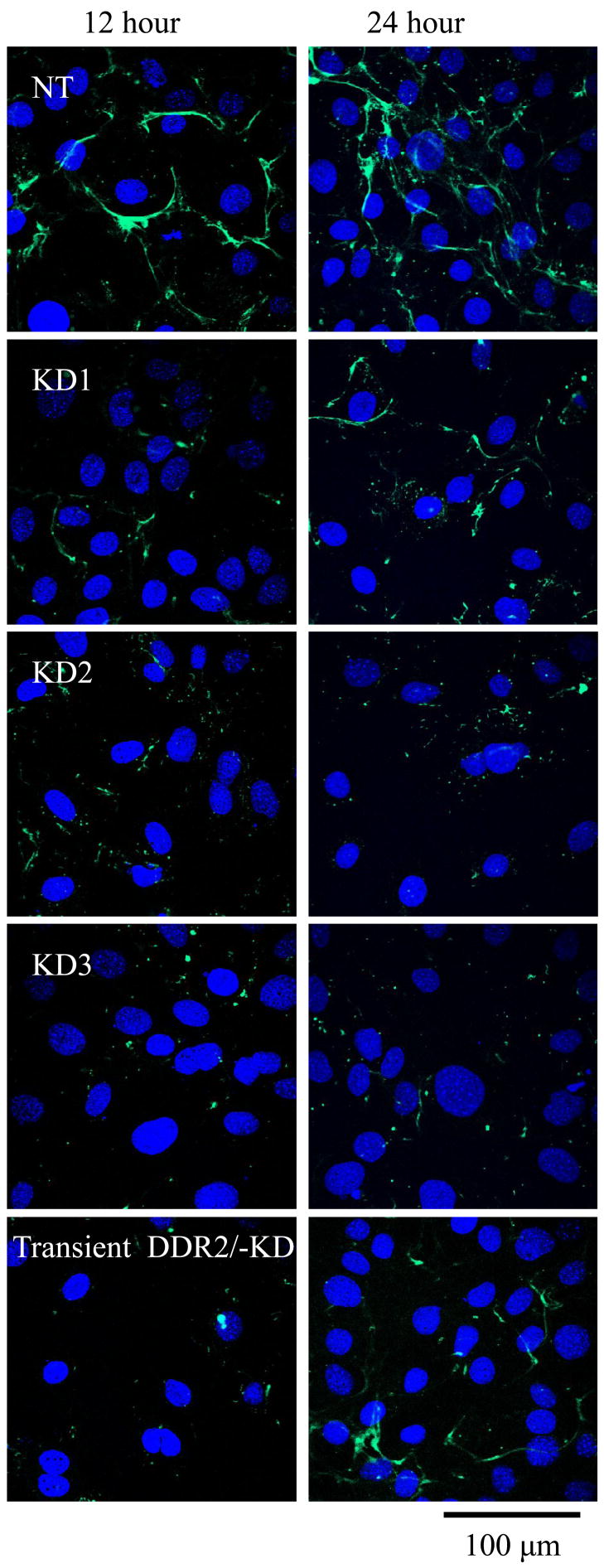

As shown above, our TEM results indicated that the expression of DDR2/-KD exhibited a slower lateral growth rate for collagen endogenously secreted by these cells. To further validate that this inhibition of collagen fibrillogenesis was due to direct interaction of DDR2/-KD with collagen and not due to a delay in secretion of collagen by the stable cell lines, we tested if expression of DDR2/-KD had an effect on the fibrillogenesis of exogenously added collagen. For this purpose, native and transiently or stably transfected DDR2/-KD clones were incubated with FITC labeled monomeric collagen. Figure 6 shows that while the samples with native cells rapidly formed collagen fibers, which increased in length with incubation time, the samples with transiently or stably transfected DDR2/-KD cells showed an inhibition in collagen fibrillogenesis at all time points (12 hour and 24 hour shown in figure). Out of the three stably transfected cells the KD1 clone shows evidence for a slightly greater fiber formation as compared to the other two clones, consistent with its lower expression level of DDR2/-KD.

Figure 6.

Collagen fibrillogenesis is reduced in DDR2/-KD expressing cells. FITC-labeled collagen was added to cell samples and allowed to incubate for the indicated time points of 12 and 24 hours. The nontransfected samples show formation and growth of collagen fibers with time. Both stable and transiently transfected cells expressing DDR2/-KD show inhibition of collagen fibrillogenesis. Out of the stable DDR2/-KD cell lines KD1 shows a relatively higher level of fiber formation consistent with its lower expression level of DDR2/-KD.

DDR2/-KD leads to reduced collagen deposition

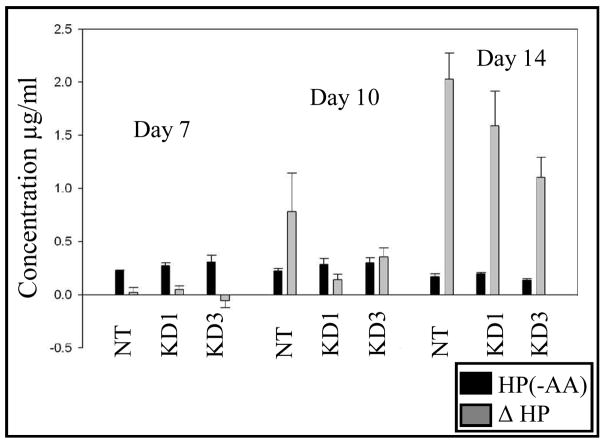

While our TEM micrographs indicate a reduced deposition of collagen in the ECM, the amount of collagen in all samples was quantified by use of the hydroxyproline (HP) assay, a well-established biochemical method for quantification of collagen content18, 37. To quantify the relative amounts of collagen deposited in the ECM in each sample, native or DDR2/-KD cells were cultured in the presence or absence of ascorbic acid and the difference in HP (for the adhered cell and ECM content) between the samples with or without ascorbic acid was ascertained. The amount of soluble collagen present in the conditioned media was not assessed. Further, a cell density assay was used to normalize the cell population due to potential variation in proliferation rates. As shown in figure 7, little or no variation occurred in the HP content for all samples when prepared in the absence of ascorbic acid, suggesting that the synthesis of collagen by the cells is not changed in native vs. DDR2/-KD stable cells. Cell samples prepared in presence of ascorbic acid exhibited a difference in their HP content of the ECM as a function of DDR2/-KD expression. The normalized HP signal for native cells was significantly larger than the KD1, KD2 (not shown) and KD3 clones, with the HP/collagen content decreasing with increasing expression of DDR2/-KD. The highest expressing clone, KD3, contained only about 45% of the collagen deposited by native cell samples for day 10 and 55% of native collagen deposited for day 14.

Figure 7.

Quantification of collagen content in the ECM by hydroxyproline (HP) assay reveals reduced deposition of collagen in DDR2/-KD cell lines. In this figure, HP(-AA) is the HP concentration in the adhered cell +ECM portion of the samples made without ascorbic acid. ΔHP is the difference in HP concentration between samples made with and without ascorbic acid. ΔHP is thus the amount of HP that is present as fibrillar collagen in the ECM. In the absence of ascorbic acid, all samples exhibited nearly the same amount of HP. Differences in ΔHP can be clearly observed for nontransfected cells vs. the cells expressing DDR2/-KD at 10 and 14 days of culture. Reduced collagen content was observed, consistent with the expression level of DDR2/-KD for stable vs. nontransfected cells.

Discussion

We demonstrate here that the DDR2 receptor even when lacking its kinase domain still remains a regulating factor in collagen fibrillogenesis by cells. Our investigations reveal that the cell-surface expression of DDR2/-KD results in collagen fibers in the ECM that are deficient in the native banded structure, are smaller in fiber diameter, exhibit delayed kinetics for collagen fibrillogenesis and a reduced collagen deposition in the ECM. These observations are consistent with our earlier results18 where we showed that the soluble DDR2 ECD when present in collagen solution in-vitro, resulted in lack of native banded structure, smaller fiber diameters and a delayed kinetics of collagen fibrillogenesis. Our current results thus signify that cell-surface anchored collagen binding proteins also preserve the capacity to regulate collagen fibrillogenesis. We thus elucidate a novel functional role for the expression of DDR2 ECD, which occurs in the full-length DDR2 protein or may be present in other unidentified DDR2 isoforms.

Our results may also provide novel insights into the functional roles of isoforms of DDR1. It is known that DDR1 can exist in five distinct isoforms in vivo, DDR1a-e21, obtained through alternative splicing. Since our DDR2/-KD construct resembles the naturally occurring kinase-dead DDR1 splice variants, DDR1d and e, and we have shown earlier that the soluble DDR1 ECD regulates collagen fibrillogenesis19; it is likely that even the DDR1d and DDR1e isoforms along with the full-length DDR1 have a functional role in collagen regulation. Although the splice variants for DDR2 are not yet characterized there are evidences to support they do exist. Several protein species for DDR2 have been detected in cultured human smooth muscle cells at various molecular weights: 130, 90, 50 and 45 kDa, along with two transcripts at 9.5 and 4.5 kb10. Independent studies have identified multiple transcripts for DDR2 in cancerous and normal cell lines14, 22–24. Our results signify the importance of identifying and characterizing the DDR2 isoforms which possess the DDR2 ECD. In addition, our results suggest that other collagen binding membrane proteins like integrins and platelet glycoprotein VI may influence collagen fibrillogenesis, especially if their soluble domains have been demonstrated to regulate collagen fibril formation25.

Three DDR2 binding sites have been mapped on the collagen triple helix by us26 for collagen type 1 and by others using the Collagen toolkit for collagen type 227. All of the three reported binding sequences are conserved in the α1 chain of collagen types 1, 2 and 3. The central motif sequence GARGQAGVMGFO corresponding to amino acids 394–405 has the highest binding affinity for DDR227. This binding site overlaps with the binding site of another soluble collagen binding protein von Willebrand factor (vWF) in collagen type 327 and is in close proximity to a binding site for decorin on collagen type 128. Although no studies have been reported on effect of vWF on collagen fibrillogenesis, decorin has been found to result in smaller collagen fiber diameter2, 29, similar to that observed by us for DDR2. It is interesting to note that majority of the collagen-binding proteins known to modulate collagen fibrillogenesis are glycoproteins. Glycosylation of collagen is considered an important factor for binding of both decorin30 and DDR27, 8 to collagen. Additionally, collagen glycosylation on the hydroxylysines can play a critical role in regulating fiber diameter in collagen fibrillogenesis31, 32. Studies addressing the role of glycosylation in DDR2 binding to collagen need further exploration, especially since DDR2 is a glycoprotein with at least one of the binding sites in close proximity to decorin.

Changes in collagen fiber diameter and rate of deposition can also arise due to various types of collagens (heterologous collagen) being incorporated into a fiber. In tissue cultures, Contard et al33 showed that fibers with measured diameters of 34 nm or less bound antibodies against type I collagen molecules while antibodies against type III collagen bound fibers with a diameter between 35nm and 54nm. In vitro studies by Birk et al34 demonstrated that collagen fiber diameter is regulated by collagen type V. They found that pure collagen type V forms small fibers (mean 25 ± 8 nm) with no apparent banded structure by TEM. Type V and type I collagens are often known to form mixed fibers with the average collagen diameter increasing with percentage of type I collagen34. The collagen fibers assembled in the ECM of mouse osteoblast cells used in this study are mostly composed of collagens types 1, 3 and 5. Further studies are required to determine if DDR2 has varying affinities for these different collagen types and if expression of DDR2 ECD results in differences in collagen composition of the fibers formed. Nevertheless, since our earlier in-vitro results18 comprising of purified collagen type 1 and purified DDR2 ECD also showed effects of DDR2 on collagen fibrillogenesis, it is unlikely that our observed differences in the present study are largely due to differences in expression levels of different collagen types.

DDR2 knock-out mice have been shown to possess skeletal defects such as shortening of long bones and irregular growth of flat bones35. These defects in knock-out animals have been explained on the basis of impaired chondrocyte and fibroblast proliferation observed in the absence of DDR2. While it is well-known that the ECM can influence cell-proliferation, no reports exist so far on the ultrastructural collagen morphology for DDR2 knock-out animals. Our results indicate that expression of DDR2 may be critical to regulate collagen deposition, which in turn may affect cell proliferation. A detailed examination of the ECM morphology in DDR2 knock out vs. wild type animals will provide a more complete understanding of the role of DDR2 in matrix turnover and cell proliferation.

The collagen receptor DDR2 (and likely DDR1) can regulate collagen by two mechanisms: by activating and upregulating MMPs, as reported earlier, and by inhibition of collagen fibrillogenesis as demonstrated in our studies. These two mechanisms give rise to a weakening of the ECM which can influence cell adhesion, migration and proliferation. One may speculate that a weakened ECM would play a different role in developing vs. adult tissues. In adult tissue a weakened ECM could result in heightened tumor invasiveness which aligns with findings of DDR2 overexpression in malignancies9–12. In developing tissue, it is possible that a weaker, or more dynamic, ECM is needed for cell proliferation; such has been reported for the developing heart36.

Taken together our results convey a novel significance of the expression level of DDR2 ECD, found in the full-length DDR2. We conclude that the DDR2 ECD when expressed on the cell surface can modulate collagen fibrillogenesis. Further, we demonstrate that collagen fibrillogenesis can be regulated by both soluble and cell-surface collagen binding proteins in a similar manner.

Materials and Methods

Creation of membrane anchored, kinase deficient DDR2 (DDR2/-KD) expression construct

An expression plasmid encoding the kinase-deficient, membrane anchored mouse DDR2 (DDR2/-KD) was generated using the full-length mouse DDR2-myc constructs obtained from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Tarrytown, NY8. The coding region of the kinase deleted DDR2 (amino acids Met-1 through Lys-562) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction utilizing the following primers: forward: 5′-3′: AGGATGATCCC-GATTCCCAGA, and reverse: 5′-3′: CAGTTTCCTGGGGAACTCTTC and Pfu TURBO polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The resulting PCR product (1689 bp) was subjected to Taq polymerase to include 3′ A-overhangs in the PCR product for enabling ligation immediately into the pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO vector using the Top10 chemically competent cells from Invitrogen. Recombinant clones were identified by restriction analysis using the double digest with KpN1 and EcoRV. The authenticity (i.e. correct orientation and in frame with the V5 coding region) of the resulting clones were verified by dideoxynucleotide sequencing.

To verify the expression of DDR2/-KD protein, mouse osteoblasts cells, MC3T3-E1 subgroup-4 (from ATCC) were transfected with our DDR2/-KD expression construct using FuGene 6 transfection reagent (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). After 36 hours of transfection the cells were lysed and the lysates subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting onto nitrocellulose membranes as described previously18. The membranes were probed with anti-V5 primary antibodies (Invitrogen) (1:1000) and imaged using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences) after incubation with anti-rabbit Ig horseradish peroxidase. The expression of endogenous DDR1 and DDR2 was tested in non-transfected MC3T3 cells using Western blotting with anti DDR1 (sc532, Santa Cruz biotechnology, Inc) and anti DDR2 (R&D systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) antibodies.

To test if DDR2/-KD undergoes collagen induced tyrosine phosphorylation, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with DDR2/-KD and serum starved for 12 hrs after 24 hrs of transfection. Thereafter the cells were stimulated with 10μg/ml collagen type I (Inamed, Fremont, CA) for 90 minutes. Whole cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting and probed with an anti-phosphotyrosine (4G10) clone (Upstate, Temecula, CA) followed by re-probing with anti-V5 primary antibody (Invitrogen).

Stable cell lines

Mouse osteoblast cells, MC3T3-E1, subgroup-4 (ATCC) were seeded (40–60% confluent) on 100mm dishes in MEM-α with 10% FBS and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (pen-G 10,000 units/ml; streptomycin 10,000 μg/ml; amphotericin B 25 μg/ml) from Gibco. MC3T3-E1 cells were subsequently transfected with the DDR2/-KD expression construct using FuGene 6 (Roche Diagnostics). Thirty-six hours after transfection, the cells were incubated with selection media containing 475μg/ml geneticin. After seven days of selection the individual surviving colonies were transferred to 35mm dishes and expression of DDR2/-KD in the lysates of the resulting stable cell lines was verified by Western blotting with anti-V5 antibodies. Three stable cell lines designated, KD1, KD2 and KD3 which expressed increasing amounts of DDR2/-KD were utilized for the following studies.

Immunocytochemistry

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with DDR2/-KD using Fugene 6 (Roche Diagnostics). After 24 hrs of transfection the cells were fixed with 2% formalin (Fischer Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) and the samples were then incubated with a DDR2 antibody raised against its extracellular domain (R&D systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). Samples were then incubated with an Alexa Fluor 546 conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and imaged on a Zeiss confocal LSM 510 microscope using a 63x oil immersion lens; a 543nm argon laser was used to excite the fluorochrome. Non-transfected cells were used as controls.

Cell Surface Biotinylation

MC3T3 cells were cultured as described and transiently transfected with DDR2/-KD construct; 24 hours after transfection, the cells were surface biotinylated by incubation with sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL) in PBS for 30 minutes on ice. The reaction was quenched by washing with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The cells were lysed in Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM PMSF, 30 ug/ml aprotinin and 15 ug/ml leupeptin. The detergent soluble fraction was recovered by centrifugation for 20 minutes at 16,000 × g, and the supernatant was subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with streptavidin-agarose beads (Pierce) for 2 hours to bind the biotinylated proteins. The beads were pelleted by centrifugation and the supernatant was incubated for an additional 2 hours with fresh streptavidin-agarose beads to remove any remaining biotinylated proteins. The streptavidin beads from the two IP reactions were pooled together, washed four times in lysis buffer and heated in LDS sample buffer at 75 °F for 10 minutes to release the bound protein. The supernatant from the second IP reaction was saved and subjected to IP with anti-V5 antibody to collect the intracellular pool of DDR2/-KD. The supernatant from the anti-V5 IP reaction was saved as well and used as the intracellular protein pool. Aliquots of the cell surface (biotinylated) protein pool (IP with strepatavidin), and intracellular DDR2/-KD pool (IP with anti-V5), were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-V5 antibody. To confirm that the biotinylation protocol did not resulted in nonspecific labeling of intracellular proteins, aliquots of the biotinylated surface protein pool and intracellular protein pool were analyzed by Western blotting and probed with antibodies against ERK2 kinase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), an intracellular protein. As an additional control, similar protocols were also performed on non-biotinylated samples, to confirm that that the streptavidin pull down is specific to biotinylated proteins.

TEM

Cells were cultured on Thermanox plastic coverslips (Nalge Nunc International, NY) kept in 35 mm dishes, in the presence of 25 μg/ml ascorbic acid, for 1 to 3 weeks as indicated. Samples were fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde overnight then osmicated for 1 hour in 1% osmium tetroxide, followed by enbloc staining with saturated uranyl acetate (aq) for 1 hour. Samples were then dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (30–100%) and embedded in an epoxy resin. Following polymerization, the 35mm dishes were discarded to obtain the resin disk. A quick insertion into liquid nitrogen facilitated the removal of the plastic coverslip from the resin disk. The resin disk was cut in half and a drop of liquid resin was used to adhere the two halves such that the cell layers are in juxtaposition. Rectangular portions of resin disk were cut out for sectioning and cell layers were cross-sectioned on a Leica Ultracut UCT ultramicrotome (Leica-Microsystems Wien, Austria). 80 nm thin sections were picked up on 200 mesh copper grids and post stained with uranyl acetate and Reynolds’s lead citrate. Sections were examined on a Zeiss EM 900 TEM (Carl-Zeiss SMT, Peabody, NY) operating at 80kV. Digital micrographs were captured on an Olympus SIS Megaview III camera (Lakewood, Colorado), at magnifications ranging from 7kX to 85kX.

Analysis of fiber diameter

Diameters of collagen fibers in the ECM were measured from TEM images using the Image J software (NIH). For each specimen type, at least two identical and independent cell-samples were made. At least two TEM grids were made from each sample and several different regions on each grid were imaged. Collagen fiber diameters were measured on cross-section or longitudinal images observed in TEM micrographs at magnifications of 30–50kX. At least 100 fiber diameters were measured for each specimen type for performing a statistical analysis comprising of average diameter, standard deviation and frequency distribution.

Hydroxyproline Assay

Quantification of hydroxyproline (HP) content in our various cell samples was performed using the method of Reddy and Enwemeka37. Four cell specimens were analyzed: Native cells and cells stably transfected with DDR2/-KD, namely colonies KD1, KD2 and KD3. For each specimen, cell samples were prepared in triplicate, with and without ascorbic acid, in order to quantify the amount of fibrillar collagen matrix present in the samples. The analysis of HP content was carried out at days 7, 10 and 14 in cell-culture.

Immediately before the hydroxyproline assay the cell population in each sample was quantified by a cell proliferation assay using Calcein-Am (BioChemika 17783). The cell samples in 6-well plates were washed twice in PBS after which 2μL of 1mM Calcein-AM stock solution was added drop wise to each well and the plates gently swirled to mix the Calcein-AM. Plates were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature, after which fluorescence signal was detected by a fluorescent plate reader using Cytofluor II software (Global Medical Instrumentation, Ramsey, MN) at an excitation wavelength of ~ 485 nm and emission at 530 nm. Once a cell count was estimated for each well, the cell density in each well was normalized with respect to the lowest cell count value measured. The corresponding normalization factor for each sample was thereafter used to normalize the HP measurement for that sample in order to account for any variation in sample growth rate.

After acquiring cell density data, all samples underwent HP analysis as follows. The supernatant was aspirated off and contents within the wells were scraped and pipetted into individual 1.5mL conical O-ring screw cap tubes (Fisher Scientific 02-681-373). All samples were then brought to a final volume of 50μl with a final concentration of 4N sodium hydroxide. Samples were then autoclaved for 20 minutes at 120 °C, after which 450μl of chloromine T reagent was added to each sample and incubated at room temperature for 25 minutes. Thereafter, 500 μl of Ehrlich’s reagent was mixed into each sample and incubated at 65 °C for 20 minutes. Finally the absorbance of each sample was measured at 560nm using a Beckman DU730 spectrophotometer. The amount of HP in each sample was ascertained by using calibration against a standard curve of HP, obtained using HP ranging from 0.5 to10 μg/ml. Collagen content was estimated by considering that hydroxyproline comprises 12.5% of collagen fibers37.

Fluorescence Microscopy

A fluorescence microscopy based assay was used to assess the rate of collagen fibrillogenesis as described earlier18, 19. Briefly, native cells, or cells transiently transfected with DDR2/-KD or stably transfected DDR2/-KD colonies were cultured on glass coverslips. FITC-labeled collagen type 1 (Sigma Chemicals, MO) was added to each sample at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. Cells were incubated with collagen for 6, 12 or 24 hours. At the end of the incubation period, cells were washed and fixed in 2% formalin (Fischer Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) for 30 minutes followed by DAPI staining. Glass coverslips were then mounted onto microscope slides using ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen Molecular Probes P36934) and examined using a 63x objective on a confocal Zeiss LSM 510 microscope. A two-photon laser was used to excite the nuclear stain at 750nm and an argon laser at 488nm was used for the FITC channel. Experiments for each specimen type were repeated at least two times.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NHLBI K25 award 5 K25 HL81442.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burgeson RE, Nimni ME. Collagen types. Molecular structure and tissue distribution. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;282:250–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neame PJ, Kay CJ, McQuillan DJ, Beales MP, Hassell JR. Independent modulation of collagen fibrillogenesis by decorin and lumican. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:859–863. doi: 10.1007/s000180050048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halász K, Kassner A, Mörgelin M, Heinegård D. COMP acts as a catalyst in collagen fibrillogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(43):31166–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705735200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalamajski S, Oldberg A. Fibromodulin binds collagen type I via Glu-353 and Lys-355 in leucine-rich repeat 11. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(37):26740–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rentz TJ, Poobalarahi F, Bornstein P, Sage EH, Bradshaw AD. SPARC regulates processing of procollagen I and collagen fibrillogenesis in dermal fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(30):22062–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicolae C, Ko YP, Miosge N, Niehoff A, Studer D, Enggist L, Hunziker EB, Paulsson M, Wagener R, Aszodi A. Abnormal collagen fibrils in cartilage of matrilin-1/matrilin-3-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(30):22163–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vogel W, Gish GD, Alves F, Pawson T. The discoidin domain receptor tyrosine kinases are activated by collagen. Mol Cell. 1997;1(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shrivastava A, Radziejewski C, Campbell E, Kovac L, McGlynn M, Ryan TE, Davis S, Goldfarb MP, Glass DJ, Lemke G, Yancopoulos GD. An orphan receptor tyrosine kinase family whose members serve as nonintegrin collagen receptors. Mol Cell. 1997;1(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamanaka R, Arao T, Yajima N, Tsuchiya N, Homma J, Tanaka R, Sano M, Oide A, Sekijima M, Nishio K. Identification of expressed genes characterizing long-term survival in malignant glioma patients. Oncogene. 2006;25(44):5994–6002. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson FK, Goransson H, Westermark B. Expression analysis of genes involved in brain tumor progression driven by retroviral insertional mutagenesis in mice. Oncogene. 2005;24(24):3896–3905. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford CE, Lau SK, Zhu CQ, Andersson T, Tsao MS, Vogel WF. Expression and mutation analysis of the discoidin domain receptors 1 and 2 in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(5):808–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chua HH, Yeh TH, Wang YP, Huang YT, Sheen TS, Lo YC, Chou YC, Tsai CH. Upregulation of discoidin domain receptor 2 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2008;30(4):427–36. doi: 10.1002/hed.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franco C, Hou G, Bendeck M. Collagens, Integrins, and the Discoidin Domain Receptors in Arterial Occlusive Disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2002;12:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(01)00165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferri N, Carragher NO, Raines EW. Role of Discoidin domain receptors 1 and 2 in human smooth muscle cell-mediated collagen remodeling: potential implications in atherosclerosis and lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1575–85. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63716-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W, Zhang YQ, Liu XP, Yao LB, Sun L. Regular expression of discoidin domain receptor 2 in the improved adjuvant-induced animal model for rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Med Sci J. 2005;20(2):133–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu L, Peng H, Wu D, Hu K, Goldring MB, Olsen BR, Li Y. Activation of the discoidin domain receptor 2 induces expression of matrix metalloproteinase 13 associated with osteoarthritis in mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(1):548–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogel W. Discoidin domain receptors: structural relations and functional implications. FASEB J. 1999;13(Suppl):S77–S82. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9001.s77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mihai C, Iscru DF, Druhan LJ, Elton TS, Agarwal G. Discoidin Domain Receptor 2 Inhibits Fibrillogenesis of Collagen Type I. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:864–876. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal G, Mihai C, Iscru DF. Interaction of Discoidin Domain Receptor 1 with Collagen type 1. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:443–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pornprasertsuk S, Duarte WR, Mochida Y, Yamauchi M. Overexpression of lysyl hydroxylase-2b leads to defective collagen fibrillogenesis and matrix mineralization. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:81–87. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alves F, Saupe S, Ledwon M, Schaub F, Hiddemann W, Vogel WF. Identification of two novel, kinase-deficient variants of discoidin domain receptor 1: differential expression in human colon cancer cell lines. FASEB J. 2001;15:1321–1323. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0626fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alves F, Vogel W, Mossie K, Millauer B, Hofler H, Ullrich A. Distinct structural characteristics of Discoidin I subfamily receptor tyrosine kinases and complementary expression in human cancer. Oncogene. 1995;10:609–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karn T, Holtrich U, Brauninger A, Bohme B, Wolf G, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, Strebhardt K. Structure, expression and chromosomal mapping of TKT from man and mouse: a new subclass of receptor tyrosine kinases with a factor VIII-like domain. Oncogene. 1993;8:3433–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai C, Lemke G. Structure and expression of the Tyro 10 receptor tyrosine kinase. Oncogene. 1994;9:877–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jokinen J, Dadu E, Nykvist P, Käpylä J, White DJ, Ivaska J, Vehviläinen P, Reunanen H, Larjava H, Häkkinen L, Heino J. Integrin-mediated cell adhesion to type I collagen fibrils. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(30):31956–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agarwal G, Kovac L, Radziejewski C, Samuelsson S. Binding of discoidin domain receptor 2 to collagen I: an atomic force microscopy investigation. Biochemistry. 2002;41(37):11091–8. doi: 10.1021/bi020087w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konitsiotis AD, Raynal N, Bihan D, Hohenester E, Farndale RW, Leitinger B. Characterization of High Affinity Binding Motifs for the Discoidin Domain Recptor DDR2 in Collagen. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6861–6868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Lullo GA, Sweeney SM, Korkko J, Ala-Kokko L, San Antonio JD. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(6):4223–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rada JA, Cornuet PK, Hassell JR. Regulation of Corneal Collagen Fibrillogenesis In Vitro by Corneal Proteoglycan (Lumican and Decorin) Core Proteins. Exp Eye Res. 1993;56:635–648. doi: 10.1006/exer.1993.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rühland C, Schönherr E, Robenek H, Hansen U, Iozzo RV, Bruckner P, Seidler DG. The glycosaminoglycan chain of decorin plays an important role in collagen fibril formation at the early stages of fibrillogenesis. FEBS J. 2007;274(16):4246–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Notbohm H, Nokelainen M, Myllyharju J, Fietzek PP, Müller PK, Kivirikko KI. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(13):8988–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reigle KL, Di Lullo G, Turner KR, Last JA, Chervoneva I, Birk DE, Funderburgh JL, Elrod E, Germann MW, Surber C, Sanderson RD, San Antonio JD. Non-enzymatic glycation of type I collagen diminishes collagen-proteoglycan binding and weakens cell adhesion. J Cell Biochem. 2008 doi: 10.1002/jcb.21735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Contard P, Lloydstone J, Perlish JS, Fleischmajer R. Collagen Fibrillogenesis in a three-dimensional fibroblast cell culture system. Cell Tissue Res. 1993;273:571–575. doi: 10.1007/BF00333710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birk DE, Fitch JM, Babiarz JM, Doane KJ, Linesenmayer TF. Collagen Fibrillogenesis in vitro: interaction of types I and V collagen regulates fibril diameter. J Cell Sci. 1990;95:649–657. doi: 10.1242/jcs.95.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Labrador JP, Azcoitia V, Tuckermann J, Lin C, Olaso E, Mañes S, Brückner K, Goergen JL, Lemke G, Yancopoulos G, Angel P, Martínez C, Klein R. The collagen receptor DDR2 regulates proliferation and its elimination leads to dwarfism. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:446–452. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morales MO, Price RL, Goldsmith EC. Expression of Discoidin Domain Receptor 2 (DDR2) in the developing heart. Microsc Microanal. 2005;11(3):260–7. doi: 10.1017/S1431927605050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddy GK, Enwemeka CS. A Simplified Method for the Analysis of Hydroxyproline in Biological Tissues. Clinical Biochemistry. 1996;29:225–229. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(96)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]