Abstract

Little is known about the neutralization properties of HIV-1 in India to optimally design and test vaccines. For this reason, a functional Env clone was obtained from each of ten newly acquired, heterosexually transmitted HIV-1 infections in Pune, Maharashtra. These clones formed a phylogenetically distinct genetic lineage within subtype C. As Env-pseudotyped viruses the clones were mostly resistant to IgG1b12, 2G12 and 2F5 but all were sensitive to 4E10. When compared to a large multi-subtype panel of Env-pseudotyped viruses (subtypes B, C and CRF02_AG) in neutralization assays with a multi-subtype panel of HIV-1-positive plasma samples, the Indian Envs were remarkably complex antigenically. With the exception of the Indian Envs, results of a hierarchical clustering analysis showed a strong subtype association with the patterns of neutralization susceptibility. From these patterns we were able to identify 19 neutralization cluster-associated amino acid signatures in gp120 and 14 signatures in the ectodomain and cytoplasmic tail of gp41. We conclude that newly transmitted Indian Envs are antigenically complex in spite of close genetic similarity. Delineation of neutralization-associated amino acid signatures provides a deeper understanding of the antigenic structure of HIV-1 Env.

Introduction

Genetic variability in the envelope glycoproteins of HIV-1 is one of the most important obstacles to overcome in the development of an effective vaccine. These glycoproteins form a trimolecular complex of three surface gp120 molecules bound non-covalently to three transmembrane gp41 molecules on the virus surface, where the trimer spike mediates cell attachment and subsequent membrane fusion events that allow the virus to enter cells (Wyatt and Sodroski, 1998). Neutralizing Abs block virus entry by binding and disabling the trimeric Env spike (Crooks et al., 2005). A high rate of mutation, combined with immune selection pressures and super-infections, have given rise to multiple genetic subtypes and circulating recombinant forms (CRFs) of the virus that need to be targeted by a globally effective vaccine. Genetic variability poses intricate problems for neutralizing Abs by altering amino acid sequences in core epitopes and by introducing structural changes in the gp120 molecule that shield key epitopes from antibody recognition (Pantophlet, 2006).

Over 90% of viral variants that drive the current global epidemic encompass six genetic subtypes of group M HIV-1: subtypes A, B, C, D, CRF01_AE and CRF02_AG (Leitner et al., 2007; McCutchan, 2000). Subtype C is the most prevalent subtype worldwide, accounting for the majority of infections in sub-Saharan Africa, China (China is a B/C recombinant that is mostly subtype C in Env) and India- the most populous regions affected by HIV-1 (McCutchan, 2000; UNAIDS, 2006). Available sequences for the env, gag and nef genes, as well as the limited full-length sequence data, suggest that subtype C strains from India form a monophyletic lineage that segregates separately as a subclade within the more diverse subtype C strains from Africa (Agnihotri et al., 2006; Agnihorti et al., 2004; Jere et al., 2004; Khan et al., 2007; Kurle et al., 2004; Shankarappa et al., 2001). One potential consequence of this limited env diversity in India could be a greater sharing of neutralization determinants as recognized by serum from HIV-1-infected individuals who reside in the same region (Lakhashe et al., 2007). A similar observation was made in small groups of HIV-1 subtype C-infected individuals in South Africa (Bures et al., 2002; Rademeyer et al., 2007), suggesting that neutralizing Ab-based vaccine immunogens might have less epitope diversity to overcome at a regional level.

There is an urgent need to understand how genetic diversity impacts the neutralization properties of the virus, especially intra- and inter-subtype differences within and between geographic locations that could influence vaccine efficacy. To facilitate these efforts, recent reports have described separate panels of early, sexually acquired reference strains for subtypes A (Blish et al., 2007), B (Li et al., 2005) and C (Li et al., 2006b). Viruses from sexual transmission are preferred because this is the major route of HIV-1 transmission world-wide (Galvin and Cohen, 2006; UNAIDS, 2006). In addition, recently transmitted viruses (pre-seroconversion or early seroconversion) might be the more relevant targets for vaccines (Chochan et al., 2005; Derdeyn et al., 2004; Frost et al., 2005; Keele et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 1993). Finally, it has been recommended that the reference strains be used as molecularly cloned Env-pseudotyped viruses for greater stability, reproducibility and quality control in neutralization assays (Mascola et al., 2005). Here we describe the sequence, biologic phenotype and neutralization properties of functional gp160 clones from sexually acquired, newly transmitted HIV-1 subtype C infections in India and we compare these clones to HIV-1 Envs from other parts of the world.

Results

Demographics and biologic properties of the molecularly cloned gp160 genes

One functional gp160 clone was selected from each of ten HIV-1-infected subjects either pre-seroconversion or during early seroconversion (Table 1). PBMC for virus isolation were collected from March 1999 to November 2000 in the Pune district of Maharashtra state in western India. Four viruses were isolated from females and six from males. HIV-1 infections were reportedly acquired through heterosexual contact in all cases. Viruses were isolated after a mean interval of 18 days after p24 antigen confirmation (range: 2-85 days). Mean viral load was 1,422,309 HIV-1 RNA copies/ml (range: 3,523 - 6,633,880) and the mean CD4 count was 422 cells/ml (range: 296-830). All molecularly cloned Env-pseudotyped primary viruses were CCR5 tropic.

Table 1.

Functional HIV-1 gp160 clones from Pune, India.

| Env clonea | Subtype | CoR | Gender | Mo/Yr isolated | Days after first p24 positive test | Plasma HIV-1 RNA copies/ml | CD4 Count (cells/ml) | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-00836-2.5 | C | R5 | F | 06/2000 | 85 | 31,104 | NDb | EF117265 |

| HIV-16845-2.22 | C | R5 | F | 08/2000 | 20 | 199,655 | 579 | EF117269 |

| HIV-16936-2.21 | C | R5 | M | 11/2000 | 7 | 492,813 | 296 | EF117270 |

| HIV-25711-2.4 | C | R5 | M | 03/1999 | 4 | 6,633,880 | 471 | EF117272 |

| HIV-25925-2.22 | C | R5 | M | 09/1999 | 7 | 616,531 | 317 | EF117273 |

| HIV-0013095-2.11 | C | R5 | F | 04/2000 | 18 | 147,143 | 583 | EF117267 |

| HIV-001428-2.42 | C | R5 | F | 08/2000 | 11 | 217,812 | 454 | EF117266 |

| HIV-16055-2.3 | C | R5 | M | 03/1999 | 2 | 534,557 | 830 | EF117268 |

| HIV-26191-2.48 | C | R5 | M | 05/2000 | 9 | 5,346,070 | 338 | EF117274 |

| HIV-25710-2.43 | C | R5 | M | 03/1999 | 19 | 3,523 | 350 | EF117271 |

All viruses were transmitted through heterosexual contact. Molecular clones were obtained from PBMC co-cultured virus isolates.

ND, not done.

Genetic analysis of the Indian Envs

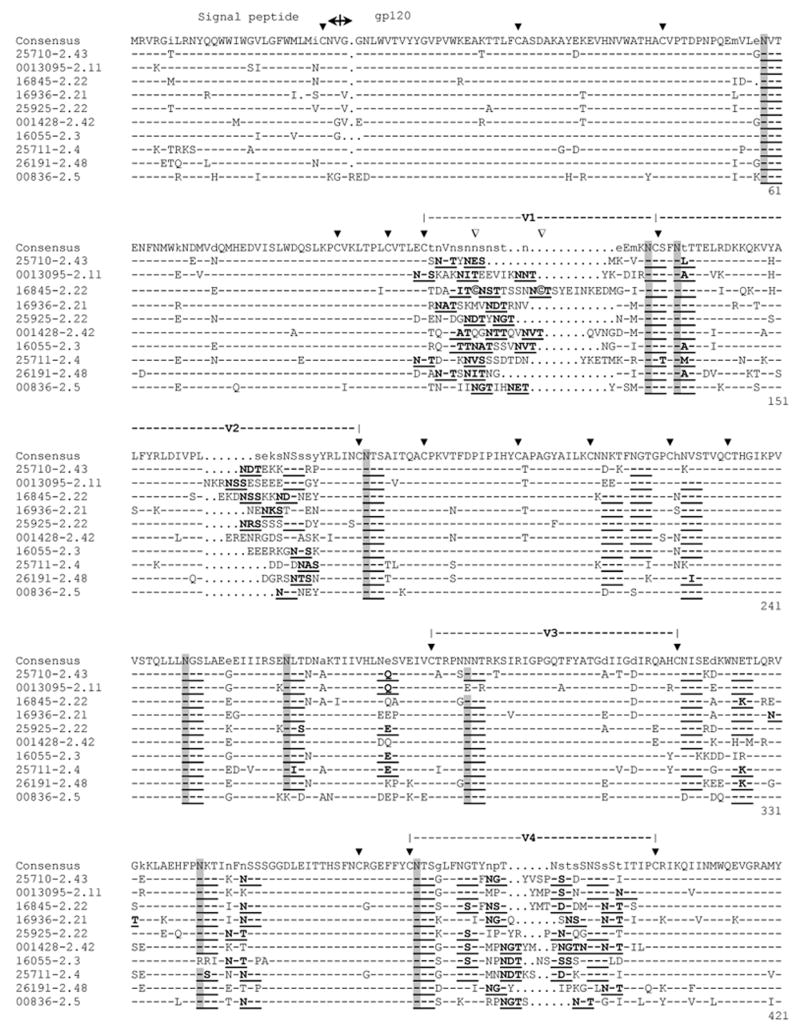

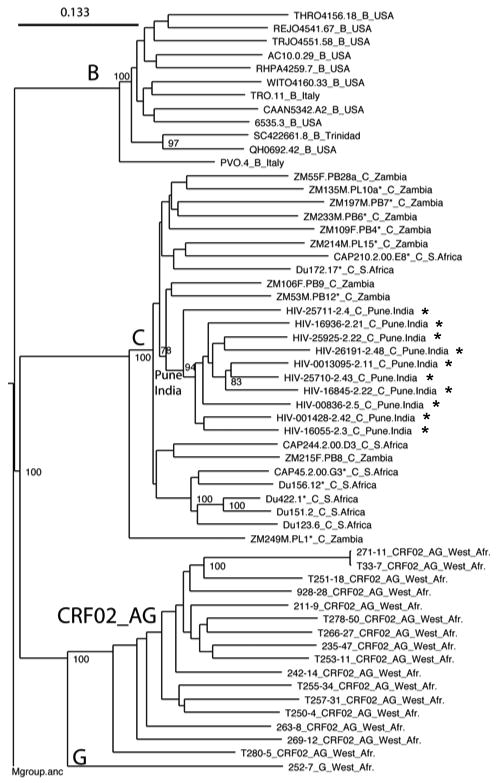

Phylogenetic analysis of full-length gp160 nucleotide sequences showed that the 10 functional Env clones from India formed a relatively conserved cluster within the more diverse subtype C (Fig. 1). All clones contained an uninterrupted env open reading frame and showed 100% conservation of cysteine residues that form the V1, V2, V3, and V4 loops of gp120 (Fig.2). Two additional cysteine residues were present in the V1 loop of one clone (HIV-16845-2.22). Several clones also exhibited variable placement of cysteine residues in the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. Considerable amino acid sequence variability was present in V1, V2, V4 and V5. Amino acid sequence variability in V3 was relatively low, whereas a region of approximately 34 amino acids immediately downstream of V3 that contains an amphipathic α2-helix was remarkably variable, as is typical of subtype C viruses (Gaschen et al., 2002; Gnanakaran et al., 2007; Li et al., 2006b).

FIG. 1.

Maximum likelihood tree indicating the phylogenetic relationships of the gp160 sequences used in the reference panel of sequences used to study neutralization phenotype. The newly characterized Indian gp160 genes are clustered together within the more diverse group of subtype C Envs from Africa, represented here by twelve gp160 genes that are recommended as standard reference reagents from South Africa and Zambia. The African sequences did not cluster by country, but there was a distinctive South African sub-cluster. The CRF 02_AG sequences 271 and T33 are highly related. Values at nodes indicate the percentage of bootstraps in which the cluster to the right was found; only values of 78% or greater are shown. The M group ancestor from the Los Alamos database was used as an outgroup.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of deduced amino acid sequences for subtype C HIV-1 gp160 genes from India. Nucleotide sequences were translated, aligned, and compared with a consensus sequence generated by MASE. Numbering of amino acid residues begins with the first residue of gp120 and does not include the signal peptide. Dashes denote sequence identity, while dots represent gaps introduced to optimize alignments. Small letters in the consensus sequence indicate sites at which fewer than 50% of the viruses share the same amino acid residue. Triangles above the consensus sequence denote cysteine residues (solid triangles indicated sequence identity, while open triangles indicate sequence variation). V1, V2, V3, V4, and V5 regions designate hypervariable HIV-1 gp120 domains. The signal peptide and Env precursor cleavage sites are indicated; “msd” denotes the membrane-spanning domain in gp41; asterisks mark in-frame stop codons. Open circles highlight altered cysteine residues. Potential N-linked glycosylation sites (NXYX motif, where X is any amino acid other than proline and Y is either serine or threonine) are bolded and underlined. Potential N-linked glycosylation sites that are conserved in at least 9 of the 10 clones are shaded.

Another typical observation was the considerable size variation in V1, V2, V4 and V5 and little or no size variation in V3 (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1). The total number of potential N-linked glycans (PNLG) on gp160 ranged from 23-31 (mean = 28.4), with a mean of 24 sites in gp120 (range 19-27) and 4 sites in the second heptad repeat (HR2) in gp41 (range 4-5). Eleven PNLG sites on gp120 and two on the gp41 ectodomain were highly conserved (Fig. 2). Heaviest clustering of PNLG on gp120 was seen in V1, V2 and V4. Most clones contained a single PNLG in V5.

Neutralization phenotype of the Indian Envs as assessed with common reagents

All 10 Indian Env clones were characterized as Env-pseudotyped viruses in neutralization assays with sCD4, four mAbs (IgG1b12, 2G12, 2F5, 4E10), TriMab, HIVIG and subtype B, C and D plasma pools. Cognate targets for the mAbs consist of a complex epitope overlapping the CD4 binding site of gp120 in the case of IgG1b12 (Pantophlet et al., 2003; Saphire et al., 2001), a glycan-specific epitope on gp120 in the case of 2G12 (Calarese et al., 2003; Sanders et al., 2002; Saphire et al., 2001), and two adjacent epitopes in the membrane proximal external region (MPER) of gp41 in the case of 2F5 and 4E10 (Barbarto et al., 2003; Brunel et al., 2006; Hagen-Braun et al., 2006; Zwick et al., 2001). The broadly cross-reactive neutralizing activity of these mAbs (Binley et al., 2004) has attracted considerable interest for vaccine design.

A majority of the Indian Envs were sensitive to sCD4 at concentrations ranging from 1.0 to 29.0 μg/ml; only one clone (HIV-00836-2.5) was resistant to sCD4 at the highest dose tested (50 μg/ml) (Table 2). As with most subtype C Envs, all Indian Envs were resistant to 2G12 and this resistance was associated with the absence of a PNLG at position 295 (HXB2 numbering; position 282 as numbered in Fig. 2) at the N-terminal base of the V3-loop (Binley et al., 2004; Gray et al., 2006, Li et al., 2006b). Only two Indian Envs were neutralized by IgG1b12 (HIV-25711-2.4 and HIV-26191-2.48); a higher percentage of subtype C viruses from other parts of the world tend to be sensitive to this mAb (Binley et al., 2004; Gray et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006b). These latter two clones were among the least sensitive to sCD4 (ID50 of 29.0 and 17.1 μg/ml), suggesting that the IgG1b12 epitope, when it is present, can be targeted even when the CD4 binding site is partially masked.

Table 2.

Neutralization phenotype of pseudotyped viruses containing molecularly cloned Env genes from India.

| ID50 in TZM-bl cells (plasma dilution)a |

ID50 in TZM-bl cells (μg/ml)a |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | Subtype B Pool | Subtype C Pool | Subtype D Pool | HIVIG | sCD4 | IgG1b12 | 2G12 | 2F5 | 4E10 | TriMab |

| HIV-00836-2.5 | 22 | 137 | 112 | 1223 | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 | 1.8 | >25 |

| HIV-16845-2.22 | <20 | 24 | 28 | 1018 | 1.0 | >50 | >50 | >50 | 0.1 | >25 |

| HIV-16936-2.21 | 48 | 317 | 72 | 1001 | 4.4 | >50 | >50 | >50 | 1.8 | >25 |

| HIV-25711-2.4 | 31 | 232 | 40 | 1513 | 29.0 | 25.9 | >50 | 36.2 | 4.2 | >25 |

| HIV-25925-2.22 | 30 | 111 | 38 | 1448 | 12.9 | >50 | >50 | >50 | 1.5 | >25 |

| HIV-0013095-2.11 | 60 | 157 | 56 | 327 | 1.1 | >50 | >50 | >50 | 0.1 | >25 |

| HIV-001428-2.42 | 71 | 190 | 41 | 783 | 5.2 | >50 | >50 | >50 | 10.1 | >25 |

| HIV-16055-2.3 | <20 | <20 | 24 | 1948 | 11.4 | >50 | >50 | >50 | 1.7 | >25 |

| HIV-26191-2.48 | <20 | 202 | 42 | 1986 | 17.1 | 4.9 | >50 | >50 | 3.1 | 14.1 |

| HIV-25710-2.43 | 43 | 364 | 65 | 339 | 2.6 | >50 | >50 | >50 | 0.2 | >25 |

| GMTb | 27 | 119 | 47 | 991 | ||||||

Values are the dilution (plasma samples) or concentration (HIVIG, CD4, IgG1b12, 2G12, 2F5, 4E10, TriMab) at which RLU were reduced 50% compared to virus control wells. TriMab is an equal concentration mixture of IgG1b12, 2G12 and 2F5.

GMT, geometric mean titer.

Regarding MPER-specific mAbs, all 10 Indian Envs were sensitive to 4E10 whereas only one Env was sensitive to 2F5 (Table 2). The single 2F5-sensitive Env (clone 25711.2-4) was the only Env that contained a DKW motif known to be a minimum requirement for 2F5 recognition (Binley et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005; Zwick et al., 2005). Many other subtype C viruses lack this motif in gp41 and are reported to be 2F5 resistant (Binley et al., 2004; Gray et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006b). The ability of 4E10 to neutralize all 10 clones is consistent with the presence of a WFXI motif that is known to be important for 4E10 recognition (Binley et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005; Zwick et al., 2005). We note that two clones (HIV-25710-2.43 and HIV-25711-2.4) contained a PNLG in the 4E10 epitope that might be expected to shield against Ab binding but this site does not appear to be glycosylated (Lee et al., 1992).

Given the general resistance to 2G12, 2F5 and IgG1b12, it was not unexpected that only one Indian Env was neutralized by TriMab (mixture of IgG1b12, 2G12, and 2F5). This Env (HIV-26191-2.48) was resistant to both 2G12 and 2F5 and was one of only two Indian Envs neutralized by IgG1b12. The inability of TriMab to neutralize the other IgG1b12-sensitive Indian Env is explained by the sub-threshold concentration of IgG1b12 in TriMab. Overall, TriMab does not appear to be suitable positive control reagent for neutralization assays with most subtype C HIV-1 viruses. HIVIG, which neutralized all 10 Indian Envs (Table 2), appears to be more suitable because of its broad reactivity against subtype C and other subtypes of HIV-1.

Among the three different HIV-1-positive plasma pools, the Indian Envs were most sensitive to the subtype C pool, followed by the subtype D and B pools, respectively (Table 2). Differences were significant (two-tailed Mann Witney tests with a 95% confidence interval) for the C pool compared to the B pool (p= 0.001) and D pool (p= 0.004) but not between the B and D pools (p= 0.105). Similar results were obtained when these same plasma pools were assayed previously against a panel of subtype C Env clones from South Africa and Zambia (Li et al., 2006b). In general, subtype C viruses appeared to be more sensitive to neutralization by subtype C plasmas than to subtype B and C plasmas from chronically infected individuals.

We also compared the potency of HIVIG against the Indian Envs and against a standard panel of 12 reference Envs each for subtypes B and C. The Indian Envs were less sensitive to HIVIG (GMT = 991 μg/ml, Table 2) than subtype B and C reference Envs (GMT subtype B panel = 375 μg/ml, p= 0.0009; GMT subtype C panel = 407 μg/ml, p= 0.0016). No significant difference was seen between the subtype B and C reference Envs (p= 0.6668).

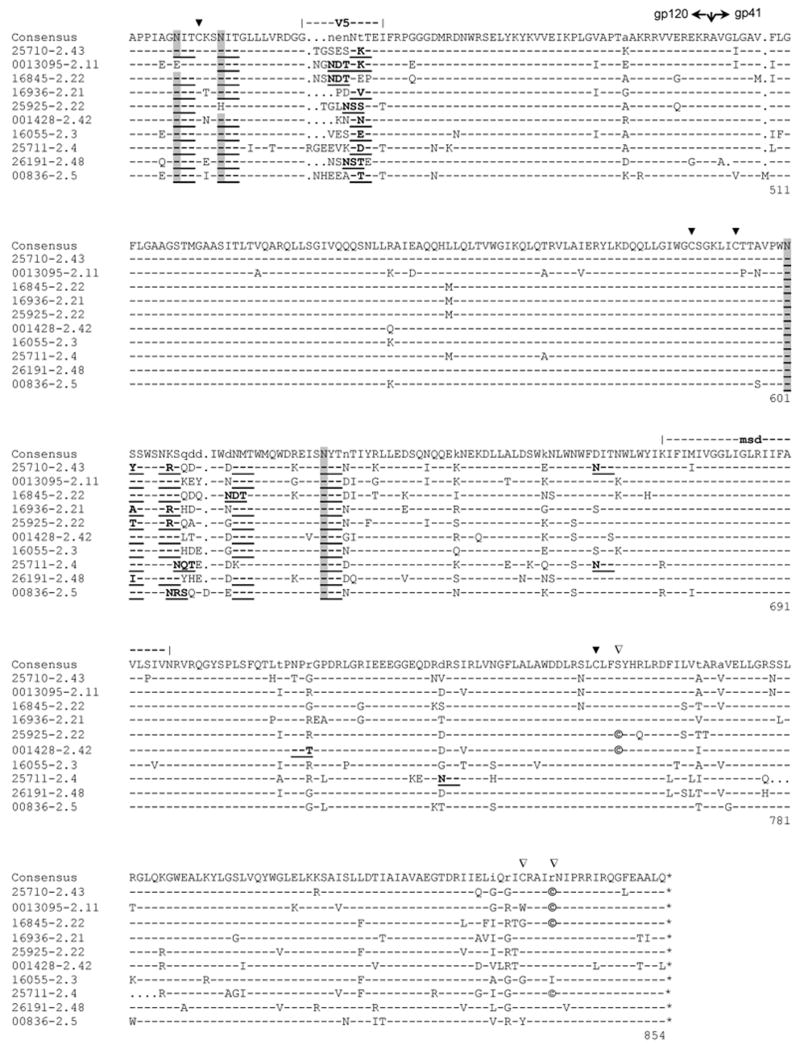

Classification of the Indian Envs as tier 2 viruses

A small fraction of HIV-1 variants are highly sensitive to neutralization and are classified as tier 1 viruses whereas most primary isolates are substantially less sensitive to neutralization (classified as tier 2) and are considered more important to target with vaccines (Mascola et al., 2005). In general, the difference in neutralization sensitivity between tier 1 and tier 2 viruses has been attributed to epitope exposure in the V3 loop and co-receptor binding domain of gp120 (Bou-Habib et al., 1994; Li et al., 2006b; Vancott et al., 1995; Xiang et al., 2002; Xiang et al., 2003). Plasma samples from presumed clade C HIV-1-infected individuals in India (n=18) and South Africa (n=6) were used to characterize the general neutralization phenotype of the Indian Env clones. As shown in Figure 3, all 10 Indian Env clones were substantially less sensitive to neutralization than the prototypic tier 1 viruses, MN and SF162.LS. In this regard, the Indian Env clones exhibited a typical tier 2 phenotype.

FIG. 3.

Neutralization-sensitivity of the Indian Envs as determined with plasma samples from chronically infected subjects in India and South Africa. Bar heights represent the geometric mean titer (GMT) of neutralizing Abs against the indicated Env-pseudotyped viruses. Black bars, plasma samples from 18 subjects in India. Gray bars, plasma samples from 6 subjects in South Africa. Paired sets were compared by two-tailed Mann Witney tests. Differences that were significant (p<0.05) are designated with an asterisk.

The data in Figure 3 were analyzed further to determine whether any Indian Env clones were preferentially neutralized by HIV-1-positive plasmas from either India or South Africa. Eight Env-pseudotyped viruses were neutralized equally by both sets of plasmas. Of the remaining three pseudoviruses, Env clone 16055-2.3 was significantly more sensitive to neutralization by the Indian plasma samples, whereas Env clones 26191-2.48 and 25711-2.4 were significantly more sensitive to neutralization by plasmas from South Africa. Interestingly, these latter two Envs were the only Indian Envs that were sensitive to IgG1b12 (Table 2).

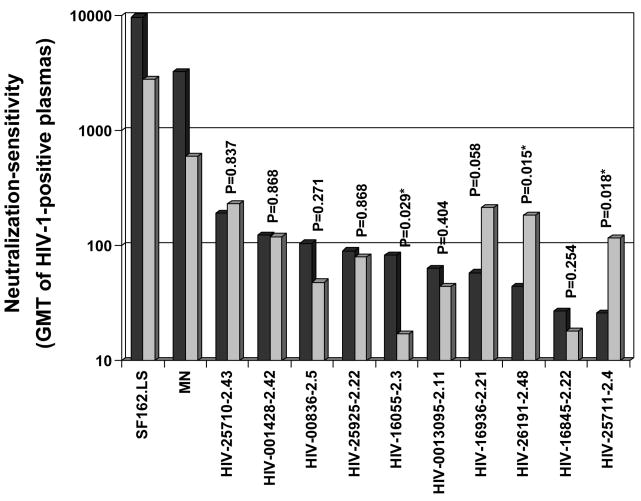

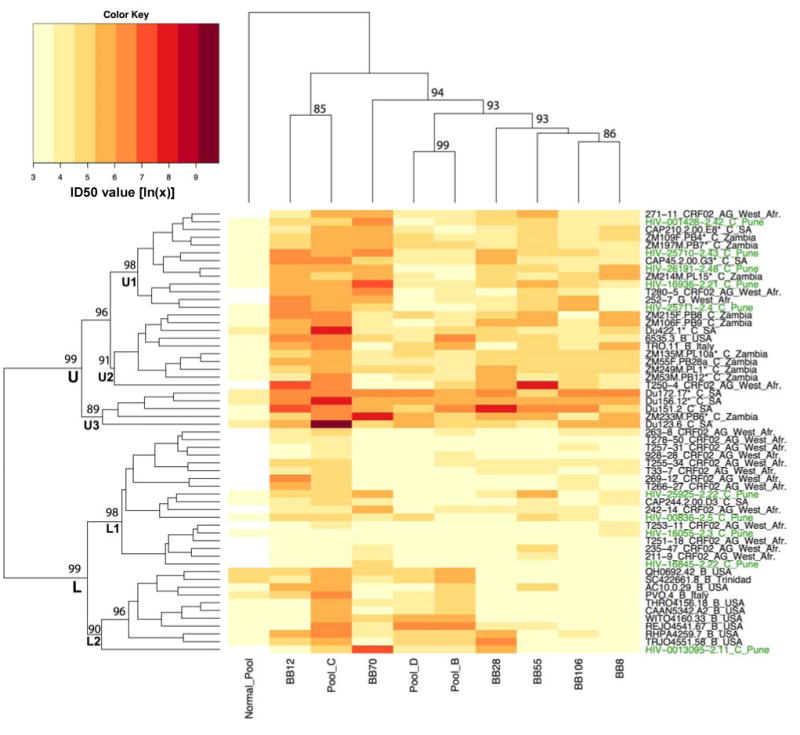

Relationships by hierarchical clustering

Because of the close genetic similarity among the Indian Envs, it was possible that they comprise a discrete antigenic group as compared to subtype A, B, C and CRF02_AG Envs from other parts of the world. To explore this possibility, agglomerative hierarchical clustering of neutralization data with HIV-1-positive plasma samples was used to determine whether subtype-specific neutralization serotypes could be revealed. This strategy clusters Envs by their susceptibility to a panel of antibodies or plasmas, while simultaneously clustering Abs and plasmas by their ability to neutralize a panel of Envs. The robustness of the clusters was assessed through bootstrap re-sampling of the data. We first analyzed neutralization data generated with the 6 individual subtype C plasma samples from South Africa and the subtype B C, and D plasma pools as assayed against a multi-subtype panel of 57 Env-pseudotyped viruses (subtypes B, C and CRF02_AG), including viruses pseudotyped with the 10 Indian Envs. Heatmap 1 (Fig. 4) shows that two main neutralization clusters were identified, in which the upper cluster (U) was generally more neutralization-sensitive than the lower cluster (L); both had 99% bootstrap support. As seen previously with mAbs (Binley et al., 2004), there was evidence for subtype-related serotypes in so much as the subtype C Envs from South Africa and Zambia mostly fell in the upper cluster whereas the subtype B reference Envs and the CRF02_AG Envs mostly fell in the lower cluster. Bootstrap analysis of the clusters show that further subdivisions of the two main clusters may be made with good bootstrap support. Thus, distinct and relatively homogenous subclusters were formed by a substantial portion of the subtype B (L2) reference Envs and the CRF02_AG Envs (L1), with CRF02_AG being the most refractive overall to neutralization. Surprisingly, the Env clones from India were scattered throughout the Heatmap, and interspersed among some of the least sensitive CRF02 and subtype B viruses.

FIG. 4.

Heatmap 1. Hierarchical clustering analysis of neutralization results generated with HIV-1-positive plasma samples from South Africa and subtype B, C and D plasma pools. Plasma samples from 6 HIV-1 subtype C-infected blood bank donors in Johannesburg, South Africa, and plasma pools from individuals infected with either HIV-1 subtype B, C or D, were assayed against a multi-subtype panel of 57 Env-pseudotyped viruses, including viruses pseudotyped with each of the 10 Indian Env clones. The dendogram for pseudovirus clustering is displayed on the left of the Heatmap, while the dendogram for the plasma clustering is displayed on the top. Env clones and plasma names are displayed at the tips of the respective dendograms. The magnitude of neutralization (log IC50 values) are denoted by color, and the numbers that correspond to the colors in the key are the natural log of the IC50 value. A “Brewer” color palette (www.ColorBrewer.org) was used to map neutralization values to colors: lower values are represented by less saturated light colors (e.g. light yellows), while higher values of neutralization are represented by more saturated dark colors (e.g. dark reds). Bootstrap values (the percentage of time a cluster was found among 1000 random with replacement resamplings of the data) of the major Env clusters are shown proximal to branch points; only high bootstrap values associated with the major groupings are shown. Some of the pairs and triplets also had high boostrap values. The upper (U) cluster referred to in the text is marked; it is more neutralization-sensitive and dominated by African subtype C sequences. The lower (L) clusters is less sensitive to neutralization and can be broken down into L1, dominated by the CRF02 AG envelopes, and L2, dominated by subtype B Envs. The subtype C Envs from India were distributed throughout the Heatmap and are labeled on the right in green text.

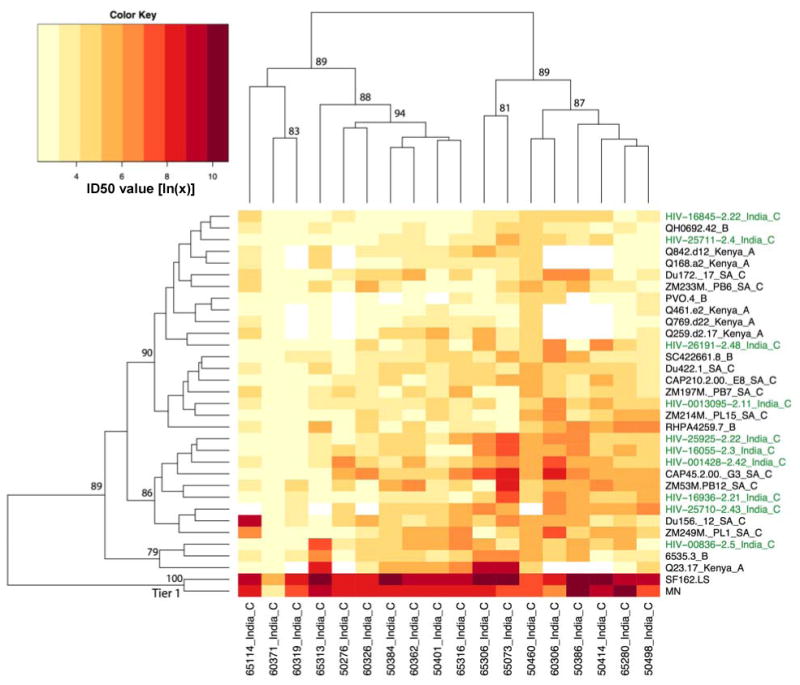

That genetically similar Env clones from India would be dispersed in a neutralization heatmap in which Envs that exhibit greater genetic diversity showed some evidence for clustering was unexpected. It also raised the question of whether the Indian Envs would exhibit clustering when assayed with geographically matched HIV-1-positive plasma samples. To address these questions, heatmap 2 (Fig. 5) shows an analysis of the neutralizing activity of plasma samples from 18 chronically infected individuals in Pune, India as assayed against pseudoviruses containing subtypes A, B, and C Envs, including viruses pseudotyped with the 10 subtype C Envs from India. Because of the limited amount of plasma that was available, fewer Env-pseudotyped viruses were assayed here than in heatmap 1, and the most resistant viruses from subtype B and CRF02 were not tested, as these latter viruses strongly contributed to the clustering pattern in the first heatmap. The second heatmap illustrates more of a continuum of moderately susceptible viruses, with the exception of the two laboratory-adapted strains at the bottom of the figure. Evidence for subtype-related neutralization serotypes (neutralization clusters predominantly containing Envs of one subtype) was not apparent using this panel of plasma samples and Envs (disregarding the two readily neutralized tier 1 viruses, MN and SF162.LS). Although the lower clusters contained 10 of 12 members belonging to subtype C, the remaining 10 subtype C Envs were scattered throughout the dendogram. In particular, the 10 newly transmitted subtype C Envs from India displayed no obvious clustering and were dispersed throughout the dendogram, as they were in Heatmap 1 (Fig. 4), despite using geographically matched plasmas. In addition, the subtype C plasma pool in figure 4 was from subjects in South Africa, and it neutralized most Envs, with two geographic/subtype based exceptions: Envs from CRF02 collected in West Africa (L1), which tended to react very poorly with all of the plasmas tested, and a handful of subtype C Envs from India (HIV-29525, -00836, -16055, -16825). Interestingly, these same four Indian Envs were often quite susceptible to individual plasma from India (Fig. 5). We conclude that the Indian Env clones are antigenically diverse in spite of close genetic similarity, suggesting that for these viruses relatively few amino acids have a relatively large effect on neutralization.

FIG. 5.

Heatmap 2. Hierarchical clustering analysis of neutralization results generated with Indian HIV-1-positive plasma samples. Plasma samples from 18 chronic HIV-1 infected individuals in Pune, India were assayed against a multi-subtype panel of Env-pseudotyped viruses, including viruses pseudotyped with each of the 10 Indian Env clones. Description of the Heatmap is as described in the legend to Figure 4. Indian Envs are shown in green. The highly neutralization-sensitive tier 1 Envs (SF162.LS and MN) cluster at the bottom of the Heatmap.

Amino acid signature pattern associations with neutralization clusters

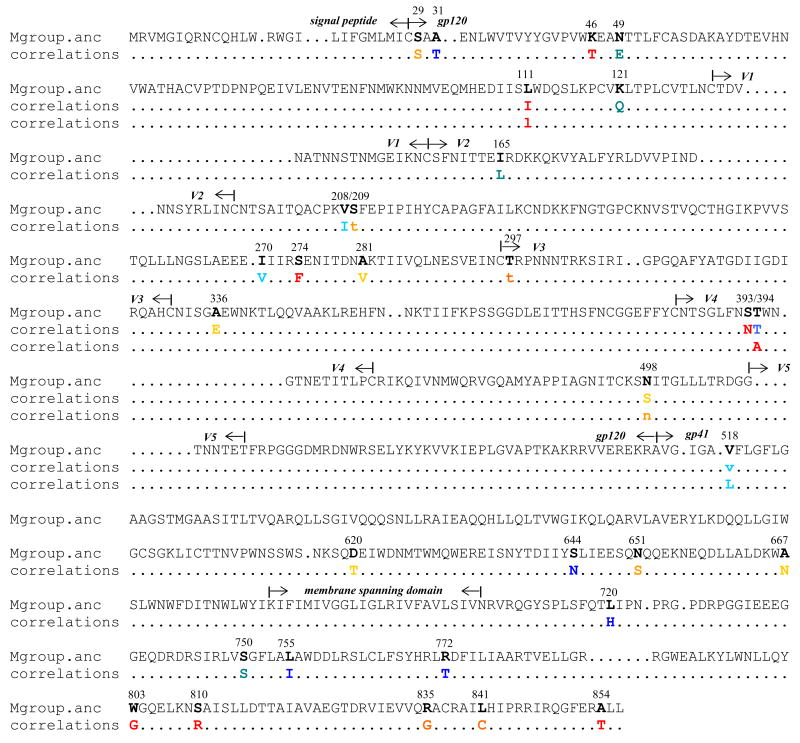

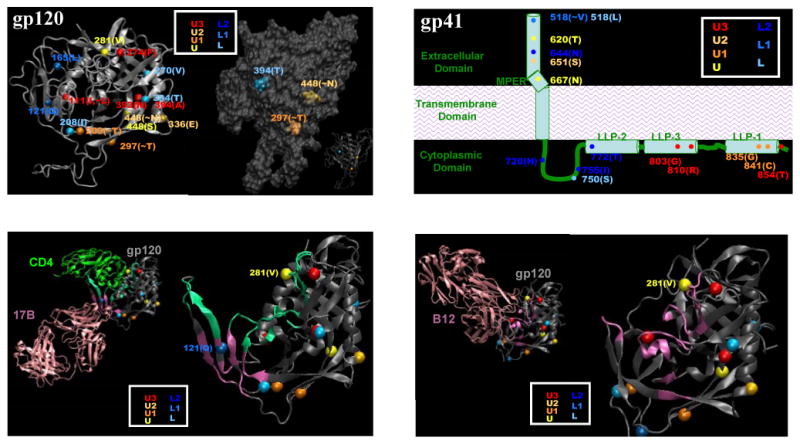

The multiple neutralization clusters seen in Heatmap 1 (Fig. 4) led to a search for amino acid signature patterns that associate with these clusters. Sequences of the Env clones in the main neutralization clusters of Heatmap 1 were analyzed using the techniques first developed by Bhattacharya et al. (Bhattacharya et al., 2007) in the context of associating genetic mutations with HLA; these methods factor in phylogenetics when statistically assessing amino acid substitutions that correlate with an attribute of the virus. We used these techniques to search for associations between genetic mutations and neutralization clusters in a way that controls for the phylogenetic history and related lineages of the sequences. Results for 47 associations with q <0.2 between a given amino acid position and neutralization phenotype revealed 19 signature sites in gp120 and 14 signature sites in gp41 (Fig. 6). More detailed information on these amino acid signatures, including their position (HXB2 positional numbering), the particular amino acids, the neutralization cluster with which they are associated, p-value, q-value, and odds ratio of the association are shown in Supplemental Materials (Supplementary Table 2).

FIG. 6.

Signature amino acid positions associated with neutralization clusters. Shown are all signature positions having q <0.20 as aligned with M group ancestor gp160 sequence from the Los Alamos database. Above each signature is its numerical position (HXB2 numbering). Colors indicate the group of the association in Heatmap 1: U, yellow; U1, dark orange; U2, light orange; U3, red; L, light blue; L1, medium blue; L2, dark blue. Upper case letters are used denote that an amino acid is associated with the group. Lower case letters are used to denote that the amino acid tends to be mutated away in the group. If a subcluster and cluster were both associated with the same amino acid pattern, we assumed they were related statistics and show only the most significant one. The complete list of sites and statistical details can be found in Supplemental Materials (Table S1).

Signature amino acid positions in gp120, as given in Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 2, were mapped to spatial locations on the gp120 molecule to illuminate potential biologic significance. Figure 7 (top left) displays these signature sites on a gp120 core structure corresponding to the X-ray crystal structure of CD4 bound to YU2 gp120 with modeled loops (Kwong et al., 2000). Four signature sites occurred in the N-terminal region of gp120 that could not be displayed because no structure is available in this region. Among the sites that could be displayed, several are of potential interest. For example, L1 cluster-associated signatures at positions 121 in β2 and 165 in the V2 loop occur in the region of gp120 that undergoes substantial conformational motions upon binding to CD4 (Kwong et al., 2002; Xiang et al., 2002). Additionally, as illustrated by the contact region for mAb 17b (Fig. 7, bottom left), signatures at positions 121 (L1 cluster) and 208 (U cluster) are potentially (or proximal to residues) involved in CCR5 co-receptor binding (Reeves et al., 2004; Rizzuto and Sodroski, 2000; Rizzuto et al., 1998). A signature at position 281, associated with the neutralization-sensitive U cluster, is in a contact region for both sCD4 and b12 (Fig. 7, bottom right) (Zhou et al., 2007). A signature associated with the neutralization-sensitive U cluster (position 336) occurred at the N-terminus of the amphipathic α2-helix (Gnanakaran et al., 2007) immediately downstream from the V3-loop (Fig. 7, top left).

FIG. 7.

Neutralization cluster-associated amino acid signatures mapped on gp120 and gp41. Color coding is the same as is in Figure 6. Top left: Signature positions mapped on a CD4-bound gp120 core structure with modeled loops; the three PNLG signature positions are shown separately for clarity. Top right: Signature positions shown on a cartoon model of gp41. Bottom left: Signature positions 281 and 121 in relationship to the receptor and 17B binding domains on gp120 crystal structure (53). Bottom right: Signature position 281 in relationship to the b12 binding domain on gp120 crystal structure [REF 107]. In the bottom figures, CD4 and antibody contact regions in gp120 are marked in light green and magneta, respectively. Contacts are defined based on crystal structures with a definition of heavy atom distance less than 7Å.

Signatures involving PNLG sequons occurred at positions 295 (the signature site is the T at position 297, immediately adjacent to the N-terminus of the V3-loop), position 392 (the site is the T at position 394 in the V4 loop) and at the N at position 448. As shown in Figure 7 (top left), all three PNLG appear on one face of the molecule, the so called ‘silent face’ of gp120 (Wyatt et al., 1998). Preservation of PNLG at position 392 was associated with the neutralization-resistance L cluster. Loss of PNLG at positions 295 and 448 was associated with the neutralization-sensitive U cluster. Although mAb 2G12 is presumed not to be an operative neutralization component in these data, the sites just mentioned are part of the 2G12 epitope (Sanders et al., 2002; Scanlan et al., 2002), suggesting that glycans originating in these three positions can be in close spatial contact. The consistent pattern of loss of PNLG being associated with greater sensitivity in neutralization clusters suggests that although a large fraction of accessible surface of gp120 is covered by carbohydrates, neutralization susceptibility can be modulated with loss/gain of glycans in a relatively small region within the silent face.

Because of a lack of three-dimensional structural data, signature amino acid positions in gp41, as given in Figure 6 and Supplementary Table 2, were plotted in a cartoon diagram (Fig. 7, top right). There were five signature sites in the ectodomain and nine signature sites in the cytoplasmic tail of gp41. As might be expected, no signature sites occurred in the transmembrane domain. One signature in the ectodomain occurred in the fusion peptide (position 518) (Freed and Martin, 1995; Kowalski et al., 1987) and another occurred in the 2F5 epitope (position 667) (Zwick et al., 2005). A third signature in the ectodomain (position 620) occurred between the two heptad repeat regions and has been implicated to modulate virus entry (Jacobs et al., 2005). Of the nine signature sites in the gp41 cytoplasmic tail, four were in the N-terminal region and were associated with neutralization resistant clusters (L clusters), whereas the other five were in the C-terminus and were associated with neutralization sensitive clusters (U clusters). Both regions play important roles in virus infectivity and in the incorporation of Env during virus assembly (Dubay et al., 1992; Freed and Martin, 1996; Yu et al., 1993).

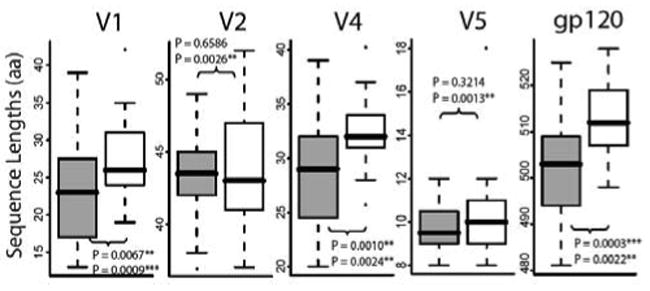

The number of PNLG sites at positions 295, 392, 448 (HXB2 numbering), when considered in combination, was significantly lower (Wilcoxon p = 0.005) in the more neutralization-sensitive U cluster compared to the more resistant L cluster, in accord with expectations that resistance can be conferred by increasing the extent of glycosylation. In addition, there was a significant difference in the total number of PNLG sites on gp120 between the U and L neutralization clusters, with the more sensitive U cluster having fewer PNLG sites (p = 0.004) and generally smaller gp120 lengths overall (p=0.0003) (Fig. 8). These two overall measures were mostly related to specific reductions in the number of PNLG in V4, and reductions in V1 and V4 loop lengths, the latter being significantly reduced in size in the more neutralization sensitive U cluster (Fig. 8, Supplementary Table 2). The p-values presented are uncorrected, and we did 10 tests; thus all survive a Bonferroni correction except for differences in the number of PNLG sites in V4, which is just a trend by this criteria.

FIG. 8.

Length of gp120 and its variable regions in association with neutralization phenotype clusters U and L. The top p-value given is based on a direct comparison that does not correct for the phylogeny, and uses a non-parametric rank sum test to compare distributions of sequence lengths in the more neutralization-sensitive U cluster (grey bars) and the more neutralization-resistant L cluster (open bars). V3 is not shown because it does not often vary in length. The lower p-value in each panel is calculated using a GLM, a statistic that indicated that the loop length associations were highly predictive of the neutralization susceptibility profile and cluster, independent of the subtype.

Given the clear subtype associations seen in Heatmap 1, if loop length and the number of PNLG are subtype-associated, some other aspect of genetic subtype-associated sequence diversity could be the origin of the observed neutralization susceptibility, and the loop length and number of PNLG may simply be confounding variables. In this regard, we corrected for the phylogeny and non-independence of points in two ways. First, we used a generalized linear model where we included the gp120 and V loop lengths, number of glycosylation sites, and genetic subtype of the virus in the model (Hastie and Pregibon, 1992). Subtype C, excluding those from Pune, and the lengths of gp120, V1, V2, V4, and V5 were each found to contribute significantly, with the significant parameters being non-Indian subtype C (p = 0.0005), the V2 loop length (p= 0.0009) and the lengths of gp120, V2, V3 and V5 (each with p < 0.003). If the subtype C Envs from India were included in the total subtype C Envs, because of their variation in the neutralization susceptibility profiles, the C subtype became much less predictive (p= 0.02). None of the tallies of the number of PNLG contributed significantly to the model, presumably because they correlate with loop length, and lengths were more predictive.

As a second test, we used Felsenstein's method of phylogenetic contrasts (http://liv.bmc.uu.se/cgi-bin/emboss/help/fcontrast) to explore the impact of phylogenetic relationships on the PNLG and sequence length associations with neutralization sensitivity. Given that this method looks for associations between continuous variables, we could not use the U and L classifications as we did for the other tests. Instead we used the overall geometric mean of the neutralization scores for each Env. Using this strategy we found that only V5 length had an association with the geometric mean of the neutralization scores, and this was marginal with p= 0.006.

Discussion

This is the first description of the neutralization properties of newly transmitted subtype C HIV-1 Envs from sexually acquired infections in India. Pune in Maharashtra state, where these viruses originated, is one of the main epicenters of HIV-1 infections in India. Moreover, the epidemic here as in other parts of India is driven mostly by heterosexual transmission (National AIDS Control Organization, 2005). Current molecular surveillance data indicate a predominance of subtype C HIV-1 across India (Maitra et al., 1999; UNAIDS, 2006) with a minor proportion of infections caused by subtypes A and B (Baskar et al., 1994; Jameel et al., 1995; Tsuchie et al., 1995) and intersubtype recombinants (Lole et al., 1999; Tripathy et al., 2005). In fact, all 10 Indian Envs studied here were pure subtype C. An important distinguishing feature of these Indian Envs was their close genetic similarity to one another compared to subtype C Envs from other parts of the world. Similar phylogenetic clustering of HIV-1 env genes has been observed in multiple Indian states (Agnihotri et al., 2006; Agnihorti et al., 2004; Khan et al., 2007; Shankarappa et al., 2001), leading to the suggestion that much of the Indian epidemic arose from the introduction of a single HIV-1 strain into the country out of the epidemic in Southern Africa (Gaschen et al., 2002; Shankarappa et al., 2001). Our limited sequence data do not disagree with this conclusion, at least for the period of time prior to when our viruses were isolated (1999-2000). A recent report on viruses collected from 1995 to 2004 suggested that Env diversity within Indian subtype C has increased in recent years (Khan et al., 2007).

The Indian Envs described here resembled subtype C Envs from other parts of the world in their general resistance to 2G12 and 2F5 and their general sensitivity to 4E10. They were different from other subtype C viruses by their infrequent neutralization by IgG1b12. Thus, epitopes for several of the most broadly neutralizing mAbs (e.g., IgG1b12, 2G12, 2F5) appear to be under-represented on Indian subtype C HIV-1 variants. The Env clones described here might be useful in delineating alternate epitopes for broadly neutralizing Abs on subtype C viruses.

Because these are the first functional molecular Env clones to be described from India, the genetic and neutralization properties of the Envs were characterized in greater detail, especially in comparison to other functional Env clones. In particular, our inclusion of a large number of viruses of different genetic subtypes permitted an examination of intra- and inter-subtype relationships. One of the more interesting and unexpected observations was that, in spite of close genetic similarity, the neutralization determinants on the Indian Envs appeared to be particularly complex. Evidence for this came from an agglomerative hierarchical clustering analysis of neutralization data generated with individual HIV-1-positive plasmas and a multi-subtype panel of HIV-1-positive plasma pools. In the analysis of two separate datasets, the Indian Envs were less likely to cluster as a result of similar neutralization susceptibility patterns than were subtype A, B, C and CRF02_AG viruses from other parts of the world. This was true even when the data being analyzed were generated with HIV-1-positive plasma samples from the same region where the Indian Envs originated as conditions that should be favorable for a clustering effect within the Indian Envs. The multiple cases of viruses that did cluster showed evidence of subtype-related serotypes, suggesting that a similar analysis of substantially larger datasets of this kind could yield a classification system to group HIV-1 variants according to neutralization serotype. Our preliminary data suggests that if such grouping is possible, neutralization serotypes and genetic subtypes will partially overlap. Results of a similar analyses of neutralization data generated with HIV-1-positive serum samples and multiple subtypes of HIV-1 primary isolates also suggested that some neutralization determinants are subtype-specific whereas others are partially shared (Brown et al., 2008; Radmeyer et al., 2007). The degree of sharing could impact the ability of a vaccine to elicit broadly neutralizing Abs, at least between subtypes A, B and C. Evidently, the extent of cross neutralization will depend on Ab specificity in as much as some of the neutralizing mAbs mentioned above are relatively subtype-specific.

The discrete neutralization clusters seen in one of our Heatmaps (Heatmap 1, Fig. 4) prompted a search for cluster-associated genetic properties that might explain the general differences in overall neutralization-sensitivity. Our observations lend support to previous findings (Bou-Habib et al., 1994; Chohan et al., 2005; Derdeyn et al., 2004; Gray et al., 2007; Li et al., 2006a; Moore and Sodroski, 1996; Reeves et al., 2004; Reitter et al., 1998; Sagar et al., 2006; Wei et al., 2003; Wyatt et al., 1995) showing that greater neutralization-sensitivity among tier 2 primary HIV-1 isolates is associated with smaller gp120s that contain shorter variable loops and fewer PNLG. In addition, our findings suggest that greater neutralization-sensitivity is more common for subtype C viruses from Africa compared to subtype B and CRF02_AG viruses, at least as defined with the HIV-1-positive plasma samples tested here. A similar observation was made recently in both the PBMC and TZM-bl assays (Brown et al., 2008). Collectively, these observations are consistent with masking mechanisms playing an important role in shaping the general neutralization phenotype of the virus. As more detailed information becomes available, an ability to predict these masking mechanisms by genetic analysis could facilitate vaccine development.

A separate analysis identify 19 neutralization cluster-associated amino acid signatures on gp120 and 14 additional signatures that spanned the ectodomain and cytoplasmic tail of gp41. Interestingly, two of the signatures in gp120, one effecting a PNLG in the α2-helix (position 336) and another in the central portion of V4 (position 393), were previously identified as signatures of escape from autologous neutralization in subtype C HIV-1-infected individuals (Rong et al., 2007). Another signature (position 281) is located in the gp120 binding site for both sCD4 and mAb b12 (Zhou et al., 2007) that has been shown also to be a major target for broadly neutralizing antibodies in serum from a small subset of HIV-1-infected individuals (Li et al., 2007). Also, a signature at position 121 resides in the bridging sheet that contributes to the coreceptor binding domain of gp120 (Reeves et al., 2004; Rizzuot and Sodroski, 2000; Rizzuto et al., 1998). This later domain, though highly conserved and strongly immunogenic, appears to be poorly exposed and rarely a target for antibody-mediated neutralization (Decker et al., 2005). Our identification of a neutralization cluster-associated amino acid signature on the rim of this region suggests that it participates to some extent in the neutralizing activity of HIV-1-positive plasma samples.

Additional signatures of interest in gp120 involved PNLG at positions 295, 392 and 448. All three PNLG have been shown to participate in the carbohydrate-specific epitope that is recognized by the broadly neutralizing mAb, 2G12 (Sanders et al., 2002; Scanlan et al., 2002). Because these PNLG were absent on the more neutralization-sensitive viruses, it is doubful that 2G12-like antibodies were responsible for the neutralization cluster-associated signatures. Consistent with this notion, a loss of PNLG at position 295 is strongly associated with broad resistance to 2G12 in subtype C viruses (Binley et al., 2004; Bures et al., 2002; Gray et al., 2006; Li et al., 2006b). It seems more likely that these three PNLG play a central role in masking neutralizing epitopes recognized by HIV-1-positive plasma samples.

Fourteen neutralization cluster-associated amino acid signatures occurred in the ectodomain and CT of gp41, suggesting a dual role for this glycoprotein in shaping the neutralization phenotype of the virus. One role would be for epitopes in the gp41 ectodomain to serve directly as targets for neutralizing antibodies. The CT, being internal and presumably inaccessible to antibodies, would play a different role, perhaps by regulating Env incorporation during virus assembly (Berlioz-Torrent et al., 1999; Byland et al., 2007; Freed and Martin, 1996; Murakami and Freed, 2000; Yu et al., 1993; Yuste et al., 2004) and by mediating allosteric changes that affect epitopes in gp120 and the gp41 ectodomain (Edwards et al., 2002; Gray et al., 2008; Kalia et al., 2005; Vzorov et al., 2005). Among the five signatures in the gp41 ectodomain, one occurred at position 667 within the MPER that is part of the epitope for broadly neutralizing mAb 2F5 (Zwick et al., 2005). Notably, no signatures occurred in the epitope for the broadly neutralizing MPER-specific mAb, 4E10. Antibodies with 2F5- and 4E10-like specificity are extremely rare in HIV-1-positive serum samples (Gray et al., 2007; Yuste et al., 2006); however, other MPER-specific antibodies might be present that could potentially neutralize (Gray et al., 2008; Gray et al., 2007). The location of four additional signatures outside the MPER suggests that other regions of the gp41 ectodomain are important for antibody-mediated virus neutralization. An additional role for the gp41 CT is suggested by multiple signatures that occurred in and around regions that have been implicated in modulating neutralization by anti-gp41 and anti-gp120 Abs (Edwards et al., 2002; Gray et al., 2008; Kalia et al., 2005; Vzorov et al., 2005). Two additional signatures (positions 750 and 803) occurred in regions that have been shown to regulate Env incorporation (Blot et al., 2003; Bültmann et al., 2001; Lopez-Vergès et al., 2006). A recent study found that increased Env spike density on SIV can be associated with decreased neutralization-sensitivity (Yuste et al., 2005).

This study began out of interest to gain information on the genetic and neutralization properties of functional molecular clones of newly transmitted HIV-1 variants from India. Because of the large multi-subtype panel of viruses characterized, the study evolved to examine complex patterns of plasma neutralizing activity as they relate to Env sequence variation. The two goals are inter-related in so much as the results help to explain how a monophyletic lineage of Indian Envs can exhibit extensive antigenic diversity. Thus, relatively small genetic changes that alter the number of N-linked glycans on gp120, modify the size of gp120 and its variable loops, and that introduce amino acid substitutions at one or more key positions in gp120 and gp41, all appear to shape the general neutralization phenotype of the virus. We caution that these results are preliminary and need to be confirmed with much larger and diverse sets of HIV-1-positive serologic reagents. Moreover, detailed molecular studies are needed to validate the neutralization cluster-associated amino acid signatures identified in this study. Caveats worth mentioning are that most of the Env clones used here, including the 10 Indian Envs, were derived by bulk PCR amplification of PBMC DNA, and they were selected on the basis of high infectivity in TZM-bl cells. A recent report describes a limiting dilution method for single genome PCR amplification (SGA) from plasma virion RNA that avoids potential artifacts caused by Taq-induced nucleotide substitutions and template switching (Salazar-Gonzalez et al., 2008). It is uncertain to what extent, if any, these potential artifacts might have impacted our results. It also remains to be seen whether our results are biased for clones that exhibit high infectivity in TZM-bl cells. These uncertainties may become apparent as similar studies are conducted with multiple SGA-derived Env clones. At the very least, the Indian Env clones described here should be useful as an initial panel of Env-pseudotyped viruses for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing Ab responses in India. They will also be useful for detailed investigations of epitope diversity and Env structure in a monophyletic lineage of HIV-1 variants that appear to be driving much of the epidemic in India. It will be of particular interest to see how the neutralization properties of these Envs from Pune compare to Envs from other regions in India, as well as to Indian Envs that are more recent in the epidemic.

Materials and methods

Viral isolates

Viruses were isolated from 10 anti-retroviral (ARV)-naïve, HIV-1 infected subjects (00836, 16845, 16936, 25711, 25925, 0013095, 001428, 16055, 26191, 25710) who were identified in a prospective cohort of patients attending sexually transmitted diseases (STD) clinics in Pune (Maharashtra), India and the surrounding area (Mehendale et al., 2002). All infections were acquired through heterosexual contact. In this cohort, consenting HIV-1 seronegative patients were screened for HIV antibodies at three month intervals (Recombigen HIV-1/HIV-2, Cambridge Biotech, Galway, Ireland and Genetic Systems, Genelabs Diagnostics, Singapore). Those who tested negative for HIV antibody but positive for HIV-1 p24 antigen (Coulter HIV-1 p24 assay, Coulter Corporation, USA) were recruited for study. Blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes (Becton Dickinson, Singapore) soon after confirmation of p24 antigenemia and enrollment into the study.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated from the whole blood by using Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma, USA) and stored in liquid nitrogen. Plasma was collected and stored at -70°C. Viruses were isolated by using a PBMC co-cultivation method (Kulkarni et al., 1999) with PBMC from the first sample collected after confirmation of p24 antigen status. HIV-1 RNA was quantified in stored plasma samples by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor test (version 1.5 Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA). Viruses were identified as HIV-1 subtype C by gag and env sequences using heteroduplex mobility assay (HMA) as described earlier (Gadkari et al., 1998) and reagents provided by NIH AIDS Research & Reference Reagent Program. Absolute CD4 cell counts were estimated on freshly collected blood samples by using two-color flow cytometry (FACSort, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA).

Other viruses

A functional gp160 clone for the R5 subtype B virus SF162.LS (Cheng-Mayer et al., 1997; Stamatatos et al., 1998) was obtained from Leonidas Stamatatos. T-cell line-adapted HIV-1MN (Gallo et al., 1984) was obtained from Robert Gallo and was propagated in H9 cells as described (Montefiori et al., 1988). Molecularly cloned gp160 genes representing standard panels of HIV-1 reference strains for subtype B (6535.3, QH0692.42, SC422661.8, PVO.4, TRO.11, AC10.0.29, RHPA4259.7, THRO4156.18, REJO4541.67, TRJO4551.58, WITO4160.33, CAAN5342.A2) and subtype C (Du123.6, Du151.2, Du156.12, Du172.17, Du422.1, ZM197M.PB7, ZM214M.PL15, ZM215F.PB8, ZM233M.PB6, ZM249M.PL1, ZM53M.PB12, ZM55F.PB28a, ZM106F.PB9, ZM109F.PB4, ZM135M.PL10a, CAP45.2.00.G3, CAP210.2.00.E8, CAP244.2.00.D3) were described previously (Li et al., 2005; Li et al., 2006b). The Kenyan subtype A Env clones Q23.17, Q842.d12, Q168.a2, Q416.e2, Q769.d22 and Q259.d2.17 (Blish et al., 2007) were obtained from Julie Overbaugh. These subtype B, C and A Envs are all from newly transmitted, sexually acquired infections. Env clones T257-31, T33-7, 263-8, T250-4, T251-18, T278-50, T255-34, T266-27, T253-11, T280-5, 271-11, 211-9, 235-47, 242-14, 269-12 and 252-7 are CRF02_AG from Cameroon; clone 928-28 is CRF02_AG from Cote d'Ivoire. All Env-pseudotyped viruses were prepared by co-transfection with an env-defective backbone plasmid (pSG3Δenv) in 293T cells as described (Li et al., 2005). Most of these Env clones are available from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (ARRRP).

Plasma samples, soluble CD4 (sCD4), and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)

Plasma samples (numbered 50276 through 75330) were obtained from 18 ARV-naïve, chronically HIV-1-infected individuals enrolled in HPTN 034; blood was collected from these individuals during routine visits to clinics at the National AIDS Research Institute, Pune, India during 2005 and 2006. Plasma samples from ARV-naive, chronically HIV-1-infected blood donors were obtained from the South African National Blood Services in Johannesburg, South Africa, as contributed to this study by Lynn Morris. A larger set of these latter blood bank plasma samples was tested for neutralization activity against three subtype C Env-pseudotyped viruses (Du151.2, Du156.12, and Du172.17) and those with greatest neutralizing activity (BB8, BB12, BB28, BB55, BB70, and BB106) were selected for characterization here. Plasma pools for subtypes B, C, and D were described previously (Li et al., 2005). Each plasma pool was comprised of plasma from 6-10 subjects who had pure subtype infections as verified by full HIV-1 genome sequencing of DNA from cryopreserved PBMC. A normal plasma pool was prepared from leukopaks from 4 HIV-1-negative subjects (BRT Laboratories, Inc., Baltimore, MD). All plasma samples were heat inactivated at 56°C for 1 h prior to assay. Informed consent was obtained from study participants as approved by local institutional review boards and biosafety committees. Blood bank samples were obtained from anonymous donors.

Recombinant sCD4 comprising the full-length extracellular domain of human CD4 and produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells was obtained from Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Tarrytown, NY). Human anti-gp120 mAb IgG1b12 was kindly provided by Dennis Burton (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). The human anti-gp120 carbohydrate-specific mAb 2G12, and the human anti-gp41 mAbs 2F5 and 4E10, were purchased from PolyMun Scientific (Vienna, Austria). TriMab (used as a positive control) is a mixture of three mAbs (IgG1b12, 2G12, and 2F5) and was prepared as a 1 mg/ml stock solution containing 333 μg of each mAb/ml in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (Li et al., 2005).

Cells

TZM-bl cells (also called JC53-BL) were obtained from the ARRRP as contributed by John Kappes and Xiaoyun Wu. This is a genetically engineered HeLa cell clone that expresses CD4, CXCR4, and CCR5 and contains Tat-responsive reporter genes for firefly luciferase and Escherichia coli β-galactosidase under regulatory control of an HIV-1 long terminal repeat (Platt et al., 1998; Wei et al., 2002). 293T/17 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Catalog no. 11268). Both cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco BRL Life Technologies) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone) and 50μg gentamicin/ml in vented T-75 culture flasks (Corning-Costar). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2-95% air environment. Cell monolayers were split 1:10 at confluence by treatment with 0.25% trypsin, 1 mM EDTA (Invitrogen).

Amplification and cloning of env/rev DNA cassettes

Complete env-rev cassettes were cloned from the DNA of cultured PBMC infected with each of the 10 Indian primary HIV-1 isolates described above. Briefly, fresh phytohemagglutinin-stimulated PBMC from healthy HIV-1-negative donors were inoculated with primary isolates that had been derived by PBMC co-culture. Infected PBMC were used as a source of DNA for PCR amplification and cloning of env-rev cassettes as described (Li et al., 2005). PCR products were inserted directly into pcDNA 3.1D/V5-His-TOPO (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). Plasmid minipreps from multiple colonies of transformed JM109 cells were screened by restriction enzyme digestion for full-length inserts. Clones with inserts in the correct orientation were screened by co-transfection with an env-deficient HIV-1 (pSG3Δenv) backbone in 293T cells to produce Env-pseudotyped viruses. Infectious Env-pseudotyped viruses were identified in a luciferase (Luc) reporter gene assay in TZM-bl cells as described (Li et al., 2005). Env clones conferring highest infectivity were selected for further characterization.

DNA sequence and phylogenetic analysis

Sequence analysis was performed by cycle sequencing and BigDye terminator chemistry with automated DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Inc; Models 3100 and 3730) as recommended by the manufacturer. Individual sequence fragments for each env clone were assembled and edited using the Sequencher program 4.2 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI). Nucleotide and deduced Env amino acid sequences were initially aligned using CLUSTAL W (Higgins and Sharp, 1989; Thompson et al., 1994) and manually adjusted for an optimal alignment using MASE (Faulkner and Jurka, 1988). A maximum likelihood tree was created assuming that the nucleotide sites evolve independently according to the General Reversible Model, with site rate variation estimated using maximum likelihood (Korber et al., 2000). The nine parameters of the model, as well as the rate at each site, were estimated using likelihood analysis. The reliability of branching orders was assessed by bootstrap analysis. Complete sequences of the gp160 genes are available from GenBank and the Los Alamos HIV Sequence Database (refer to Table 1 for accession numbers).

Pseudovirus preparation, titration and analysis of coreceptor usage

Env-pseudotyped viruses were prepared, titrated and analyzed for coreceptor usage as described (Li et al., 2005). Briefly, exponentially dividing 293T cells were cotransfected with rev/env expression plasmid and an env-deficient HIV-1 backbone vector (pSG3ΔEnv). Pseudovirus-containing culture supernatants were harvested 2 days after transfection, filtered (0.45 micron pore size) and stored at -80°C in 1 ml aliquots. The 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) was determined in TZM-bl cells. Coreceptor usage was determined in TZM-bl cells by measuring reductions in infectivity in the presence of the CXCR4 and CCR5 antagonists AMD 3100 and TAK-779, respectively.

Neutralization assay

Neutralizing Abs were measured as a function of reductions in luciferase reporter gene expression after a single round of infection in TZM-bl cells as described (Li et al., 2005; Monterfiori, 2004). This assay is a modified version of the assay as described previously (Wei et al., 2002, Wei et al., 2003). Briefly, 200 TCID50 of pseudovirus was incubated with serial 3-fold dilutions of serum sample in triplicate in a total volume of 150 μl for 1 hr at 37°C in 96-well flat-bottom culture plates. Freshly trypsinized cells (10,000 cells in 100 μl of growth medium containing 75 μg/ml DEAE dextran) were added to each well. One set of control wells received cells + pseudovirus (virus control) and another set received cells only (background control). After 48 hour incubation, 100 μl of cells was transferred to 96-well black solid plates (Costar) for measurements of luminescence using the Britelite Luminescence Reporter Gene Assay System (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The 50% inhibitory dose (ID50) was defined as either the serum dilution or sample concentration (in the case of sCD4 and mAbs) that caused a 50% reduction in RLU compared to virus control wells after subtraction of background RLU. Assay stocks of Env-pseudotyped viruses were prepared by transfection in 293T cells and were titrated in TZM-bl cells as described (Li et al., 2005; Montefiori, 2004).

Two-dimensional hierarchical clustering analyses

Neutralization data were clustered as described (Binley et al., 2004), using the hierarchical clustering function (hclust) and display function (Heatmap) of the R statistical computing environment (www.r-project.org). The “hclust”, which employs an agglomerative clustering algorithm to cluster both the rows and columns of tabular data separately, was applied to tabular neutralization data containing log (IC50) values. Algorithm specifications of Euclidean distance and “complete” method of agglomeration were used. After individually clustering the rows (pseudoviruses) and the columns (plasmas), the function “Heatmap” then simultaneously displayed the separate pseudovirus and plasma clusterings in one graphic called a Heatmap. Bootstrap values of cluster stability were obtained via the “pvclust” package.

Correlating genetic mutation to neutralization phenotype

Phylogenetically corrected associations of genetic mutation and neutralization phenotype clusters were obtained using the techniques developed by Bhattacharya et al. (Bhattacharya et al., 2007) and applied in the context of associating genetic mutations with HLA.

Structural mapping of signature positions

The core structure of gp120 corresponding to the X-ray structure of CD4-bound YU2 gp120 (Kwong et al., 2000) was used for mapping cluster associated mutations. Variable loops V1V2 and V3 were modeled for clarity as described previously (Blay et al., 2006). Modeling calculations were performed using a modified version of AMBER (Pearlman et al., 1995). Signature positions were mapped onto this structure based on the alignment of sequences. Three-dimensional images were generated using VMD (Humphrey et al., 1996). The positional numbering refers to HXB2.

Statistical analyses

The neutralizing potencies of HIV-1-positive plasma samples against different sets of Env-pseudotyped viruses were compared by using two-tailed Mann Witney tests with a 95% confidence interval (GraphPad Prism software, San Diego, CA). For the comparison of neutralization titers, values <20 (lowest sample dilution tested) were assigned a value of 10. Differences were considered significant if P was <0.05. Other statistical analyses that were used are described in the text.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

GenBank accession numbers for the Indian HIV-1 gp160 sequences in this study are EF117265.1 - EF117274.1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the staff of the “Acute Pathogenesis of HIV-1 Infection” project, National AIDS Research Institute, Pune, India who helped in collecting the samples and in generating the data. This work was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIAID, NIH) (AI30034) and by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (#38619). This work was also supported in part by NIAID, NIH (AI 33879-02), NIH-NCRR OPD-GCRC (5M01RR00722), the NIH-Fogarty International Center (D43TW0000), and intramural research grants from the Indian Council of Medical Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in the paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References

- Agnihotri KD, Tripathy SP, Jere AJ, Kale SM, Paranjape RS. Molecular analysis of gp41 sequences of HIV-1 type 1 subtype C from India. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:345–351. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000209898.67007.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnihorti K, Tripathy S, Jere A, Jadhav S, Kurle S, Paranjape R. gp120 sequences from HIV type 1 subtype C early seroconverters in India. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:889–894. doi: 10.1089/0889222041725217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbato G, Bianchi E, Ingallinella P, Hurn WH, Miller MD, Ciliberto G, Cortese R, Bazzo R, Shiver JW, Pessi A. Structural analysis of the epitope of the anti-HIV antibody 2F5 sheds light into its mechanism of neutralization and HIV fusion. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:1101–1115. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00611-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskar PV, Ray SC, Rao R, Quinn TC, Hildreth JE, Bollinger RC. Presence in India of HIV type 1 similar to North American strains. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:1039–1041. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlioz-Torrent C, Shacklett BL, Erdtmann L, Delamarre L, Bouchaert I, Sonigo P, Dokhelar MC, Benarous R. Interactions of the cytoplasmic domains of human and simian retroviral transmembrane proteins with components of the clathrin adaptor complexs modulate intracellular and cell surface expression of envelope glycoproteins. J Virol. 1999;73:1350–1361. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1350-1361.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya T, Daniels M, Heckerman D, Foley B, Frahm N, Kadie C, Carlson J, Yusim K, McMahon B, Gaschen B, Mallal S, Mullins JI, Nickle DC, Herbeck J, Rousseau C, Learn GH, Miura T, Brander C, Walker B, Korber B. Founder effects in the assessment of HIV polymorphisms and HLA allele associations. Science. 2007;315:1583–1586. doi: 10.1126/science.1131528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binley J, Wrin T, Korber B, Zwick M, Wang M, Chappey C, Stiegler G, Kunert R, Zolla-Pazner S, Katinger H, Petropoulos C, Burton D. Comprehensive cross-subtype neutralization analysis of a panel of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 2004;78:13232–13252. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13232-13252.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blay WM, Gnanakaran S, Foley B, Doria-Rose NA, Korber BT, Haigwood NL. Consistent patterns of change during the divergence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope from that of the inoculated virus in simian/human immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Virol. 2006;80:999–1014. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.999-1014.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blish CA, Nedellec R, Mandaliya K, Mosier DE, Overbaugh J. HIV-1 subtype A envelope variants from early in infection have variable sensitivity to neutralization and to inhibitors of viral entry. AIDS. 2007;21:693–702. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32805e8727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blot G, Janvier K, Le Panse S, Benarous R, Torrent-Berloiz C. Targeting of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope to the trans-Golgi network through binding to TIP47 is required for env incorporation into virions and infectivity. J Virol. 2003;77:6931–6945. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6931-6945.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bou-Habib DC, Roderiquez G, Oravecz T, Berman PW, Lusso P, Norcross MA. Cryptic nature of envelope V3 region epitopes protects primary monocytotropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from antibody neutralization. J Virol. 1994;68:6006–6013. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6006-6013.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BK, Wieczorek L, Sanders-Buell E, Borges AR, Robb ML, Birx DL, Michael NL, McCutchan FE, Polonis VR. Cross-clade neutralization patterns among HIV-1 strains from the six major clades of the pandemic evaluated and compared in two different models. Virol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.02.022. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunel FM, Zwick MB, Cardosa RMF, Nelson JD, Wilson IA, Burton DR, Dawson PE. Structure-function analysis of the epitope for 4E10, a broadly neutralizing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody. J Virol. 2006;80:1680–1687. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1680-1687.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bültmann A, Muranyi W, Seed B, Haas J. Identification of two sequences in the cytoplasmic tail of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein that inhibit cell surface expression. J Virol. 2001;75:5263–5276. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5263-5276.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bures R, Morris L, Williamson C, Ramjee G, Deers M, Fiscus SA, Karim SA, Montefiori DC. Regional clustering of shared neutralization determinants on primary isolates of subtype C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from South Africa. J Virol. 2002;76:2233–2244. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2233-2244.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byland R, Vance PJ, Hoxie JA, Marsh M. A conserved dileucine motif mediates clathrin and AP-2-dependent endocytosis of the HIV-1 envelope protein. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:414–425. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarese DA, Scanlan CN, Zwick MB, Deechongkit S, Mimura Y, Kunert R, Zhu P, Wormald MR, Stanfield RL, Roux KH, Kelly JW, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Katinger H, Burton DR, Wilson IA. Antibody domain exchange is an immmunologic solution to carbohydrate cluster recognition. Science. 2003;300:2065–2071. doi: 10.1126/science.1083182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng-Mayer C, Liu R, Landau NR, Stamatatos L. Macrophage tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and utilization of the CC-CKR5 coreceptor. J Virol. 1997;71:1657–1661. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1657-1661.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chohan B, Lang D, Sagar M, Korber B, Lavreys L, Richardson B, Overbaugh J. Selection for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycosylation variants with shorter V1-V2 loop sequences occurs during transmission of certain genetic subtypes and may impact viral RNA levels. J Virol. 2005;79:6528–6531. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6528-6531.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks ET, Moore PL, Richman D, Robinson J, Crooks JA, Franti M, Schulke N, Binley JM. Characterizing anti-HIV monoclonal antibodies and immune sera by defining the mechanism of neutralization. Human Antibodies. 2005;14:101–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker J, Bibollet-Ruche F, Wei X, Wang S, Levy DN, Wang W, Delaporte E, Peeters M, Derdeyn CA, Allen S, Hunter E, Saag MS, Hoxie JA, Hahn BH, Kwong PD, Robinson JE, Shaw GM. Antigenic conservation and immunogenicity of the HIV coreceptor binding site. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1407–1419. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derdeyn CA, Decker JM, Bibollet-Ruche F, Mokili JL, Muldoon M, Denham SA, Heil ML, Kasolo F, Musonda R, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Korber BT, Allen S, Hunter E. Envelope-constrained neutralization-sensitive HIV-1 after heterosexual transmission. Science. 2004;303:2019–2022. doi: 10.1126/science.1093137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubay JW, Roberts SJ, Hahn BH, Hunter E. Truncation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein cytoplasmic domain blocks virus infectivity. J Virol. 1992;66:6616–6625. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6616-6625.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards TG, Wyss S, Reeves JD, Zolla-Pazner S, Hoxie JA, Doms RW, Baribaud F. Truncation of the cytoplasmic domain induces exposure of conserved regions in the ectodomain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein. J Virol. 2002;76:2683–2691. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.6.2683-2691.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner DM, Jurka J. Multiple aligned sequence editor (MASE) Trends Biochem Sci. 1988;13:321–322. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(88)90129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed EO, Martin MA. The role of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins in virus infection. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23883–23886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed EO, Martin MA. Domains of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into virions. J Virol. 1996;70:341–351. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.341-351.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost SDW, Liu Y, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Chappey C, Wrin T, Petropoulos CJ, Little SJ, Richman DD. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) envelope variation and neutralizing antibody responses during transmission of HIV-1 subtype. B J Virol. 2005;79:6523–6527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6523-6527.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadkari DA, Moore D, Sheppard HW, Kulkarni SS, Mehendale SM, Bollinger RC. Transmission of genetically diverse strains of HIV-1 in Pune, India. Indian J Med Res. 1998;107:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo RC, Salahuddin SZ, Popovic M, Shearer GM, Kaplan M, Haynes BF, Palker TJ, Redfield R, Oleske J, Safai B, White G, Foster P, Markham PD. Frequent detection and isolation of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and at risk for AIDS. Science. 1984;224:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.6200936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin SR, Cohen MS. Genital tract reservoirs. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2006;1:162–166. doi: 10.1097/01.COH.0000199799.06454.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaschen B, Taylor J, Yusim K, Foley B, Gao F, Lang D, Novitsky V, Haynes B, Hahn BH, Bhattacharya T, Korber B. Diversity considerations in HIV-1 vaccine selection. Science. 2002;296:2354–2360. doi: 10.1126/science.1070441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnanakaran S, Lang D, Daniels M, Bhattacharya T, Derdeyn CA, Korber B. Clade-specific differences between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clades B and C: diversity and correlations in C3-V4 regions of gp120. J Virol. 2007;81:4886–4891. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01954-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray ES, Moore PL, Bibollet-Ruche F, Li H, Decker JM, Meyers T, Shaw GM, Morris L. 4E10-resistant variants in a human immunodeficiency type 1 subtype C-infected individual with an anti-membrane-proximal external region-neutralizing antibody response. J Virol. 2008;82:2367–2375. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02161-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray ES, Moore PL, Choge IA, Decker JK, Bibollet-Ruche F, Li H, Leseka N, Treurnicht F, Mlisana K, Shaw GM, Abdool Karim SS, Williamson C, Morris L. Neutralizing antibody responses in acute human immunodeficiency virus sybtype C infection. J Virol. 2007;81:6187–6196. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00239-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray ES, Meyers T, Gray G, Montefiori DC, Morris L. Insensitivity of pediatric HIV-1 subtype C viruses to broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies raised against subtype. B PLoS Med. 2006;3:1023–1031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen-Braun C, Katinger H, Tomer KB. The HIV-neutralizing monoclonal antibody 4E10 recognizes N-terminal sequences on the native antigen. J Immunol. 2006;176:7471–7481. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastie TJ, Pregibon D. In: Generalized linear models Chapter 6 of Statistical Models in S. Chambers JM, Hastie TJ, editors. Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DG, Sharp PM. Fast and sensitive multiple sequence alignments on a microcomputer. Comput Appl Biosci. 1989;5:151–153. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/5.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner T, Foley B, Hahn B, Marx P, McCutchan F, Mellors J, Wolinsky S, Korber B, editors. HIV Sequence Compendium 2006/2007. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory; 2007. LA-UR number 07-4826. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD-Visual Molecular Dynamics. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs A, Sen J, Rong L, Caffrey M. Alanine scanning mutants of the HIV gp41 loop. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27284–27288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414411200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameel S, Zafrullah M, Ahmad M, Kapoor GS, Sehgal S. A genetic analysis of HIV-1 from Punjab, India reveals the presence of multiple variants. AIDS. 1995;9:685–690. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jere A, Tripathy S, Agnihotri K, Jadhav S, Paranjape R. Genetic analysis of Indian HIV-1 nef: subtyping, variability and implications. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia V, Sarkar S, Gupta P, Montelaro RC. Antibody neutralization escape mediated by point mutations in the intracytoplasmic tail of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41. J Virol. 2005;79:2097–2107. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2097-2107.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keele BF, Giorgi EE, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Decker JM, Pham KT, Salazar MG, Sun C, Grayson T, Wang S, Li H, Wei X, Jiang C, Kirchherr JL, Gao F, Anderson JA, Ping LH, Swansrom R, Tomaras GD, Blattner WA, Goepfert PA, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Delwart EL, Busch MP, Cohen MS, Montefiori DC, Haynes BF, Gashen B, Athreya GS, Lee HY, Wood N, Seoighe C, Perelson AS, Battacharya T, Korber BT, Hahn BH, Shaw GM. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2008;105:7552–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan IF, Vajpayee M, Prasad VVSP, Seth P. Genetic diversity of HIV type 1 subtype C env gene sequences from India. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:934–940. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber B, Muldoon M, Theiler J, Gao F, Gupta R, Lapedes A, Hahn BH, Wolinsky S, Bhattacharya T. Timing the ancestor of the HIV-1 pandemic strains. Science. 2000;288:1789–1796. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski M, Potz J, Basiripour L, Dorfman T, Goh WC, Terwilliger E, Dayton A, Rosen C, Haseltine W, Sodroski J. Functional regions of the envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Science. 1987;237:1351–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.3629244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni SS, Tripathy SP, Paranjape RS, Mani NS, Joshi DR, Patil U. Isolation and preliminary characterization of two HIV-2 strains from Pune, India. Indian J Med Res. 1999;109:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]